Abstract

Objectives. We investigated the links between working for pay and adolescent tobacco use to determine whether working for pay increases smoking risk.

Methods. We performed retrospective and prospective analyses using data from a cohort of 799 predominantly African American students in Baltimore, Md, who had been followed since the first grade.

Results. At the 10th year of follow-up, when the adolescents were aged 14 to 18 years, there was a positive relationship between the time they spent working for pay and current tobacco use. This relationship was attenuated somewhat after adjustment for potential selection effects. Adolescents who spent more than 10 hours per week working for pay also tended to initiate tobacco use earlier than did their peers. Among adolescents who had not yet used tobacco, those who started to work 1 year after assessment and those who worked over 2 consecutive assessments had an elevated risk of initiating use relative to adolescents who did not start working.

Conclusions. There is a strong link between working for pay and adolescent tobacco use. Policymakers should monitor the conditions under which young people work to help minimize young workers’ tobacco use and potential for initiating use.

Although progress has been made in reducing cigarette smoking among adolescents since the call to do so in Healthy People 2010, efforts are needed to achieve further reductions.1,2 Generally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends 6 strategies to reduce smoking among adolescents, none of which are geared specifically toward adolescents who are employed This is unfortunate because the amount of time young people spend working for pay has been positively associated with smoking behaviors or scales of substance use of which tobacco use is often a component.4–10

Compared with other social domains commonly associated with adolescence (families, neighborhoods, schools, and peer groups), working has not been thoroughly investigated as a risk factor for adolescent tobacco use.11 However, there are significant reasons why the public health community should focus more attention on this domain. Work is typically perceived as a province of adulthood; however, studies have indicated that nearly all high school students work for pay at some point during the school year.5,12,13 Most research on work among adolescents has focused on samples of middle-class adolescents for whom employment opportunities are plentiful and employment is common. It is possible that positive associations between work and tobacco use across samples located in diverse socioeconomic communities might indicate that tobacco use among adolescents may respond to macrolevel policy changes that restrict the hours that adolescents can work or the jobs they can hold legally.14,15 The workplace could also be considered as a location for antismoking prevention programs or policies.

We investigated whether working for pay was associated with past, current, and incident tobacco use among adolescents. Although the relationship among adolescents between working and substance use has been seen across many studies, there is a gap in our understanding about whether working contributes to the development of smoking behaviors and, thus, can be modified by workplace policies and prevention programs.

Using data from an urban-based community cohort of adolescents followed annually since the first grade, we investigated whether working for pay at or around 10th grade is positively associated with current use of tobacco. Some researchers suspect that the positive relationship between work and smoking is the result of a selection effect, whereby the same adolescents more likely to use tobacco are those adolescents more likely to work (or devote a significant amount of time to work) during high school.7,10,16–18 Finally, we tested whether adolescents who started working or continued to work between 2 consecutive years had an elevated risk of initiating tobacco use compared with adolescents who did not work during this interval.

METHODS

Sample

We obtained data from the second generation of the Baltimore Prevention and Intervention Research Center (PIRC) studies. In 1993, 678 students who were entering first grade classrooms in participating schools in west Baltimore and their families were invited to participate in a randomized controlled trial aimed at improving young people’s shy and aggressive behaviors. These students were assigned to 1 of 2 classroom-based prevention programs or to a control group. The results of the intervention have been described elsewhere.19–22 Students and their families were and continue to be interviewed annually since the first grade, although no assessments were conducted in the fourth and fifth years of follow-up. During the first year, 121 additional students joined the classrooms after the initial recruitment, although as of year 11, attempts were made to contact only members of the originally recruited first grade sample because of the primary goal of the follow-up (i.e., to assess distal effects of the first grade intervention).

Beginning at the sixth year of follow-up, all the adolescents were asked about their experiences with tobacco, and beginning at the 10th year of follow-up, they were asked about the average time they spent working for pay during the school year. Of the total 799 adolescents with some information at grade 1, 570 were interviewed at year 10 (501 of the 678 original recruits; 69 of the additional 121), 515 were interviewed at year 11, and 488 were interviewed in both years 10 and 11 (by definition, all were from the original 678). Parents received consent information, and adolescents completed an assent procedure and were assured of their confidentiality before each interview.

Analysis

In the first stage of the analysis, we examined the link between working for pay and substance use at the 10th year of follow-up, when the adolescents were aged between 14 and 18 years (the mean age was 16 years). Current tobacco use was a dichotomous variable that indicated use in the past 30 days. We collected work intensity (the average number of hours adolescents worked per week during the school year) in 5-hour intervals; we subsequently categorized these responses into 1 of 3 categories of work: not working during the past year, working an average of 1 to 10 hours per week (moderate work intensity), or working an average of more than 10 hours per week (high work intensity). In separate analyses, we used other thresholds (15 hours and 20 hours), which yielded qualitatively similar, although less precise, results (because of the smaller sizes of the high-intensity group). We used logistic regression to assess the relationship between working for pay and currently using tobacco.

To examine the possibility that adolescents more likely to use tobacco were also more likely to work at year 10 (i.e., a potential selection effect), early childhood characteristics previously associated with adolescent tobacco use were incorporated into the logistic model. We included teachers’ reports of adolescents’ early aggressive behaviors as exhibited in the first grade in the model.23 From year 6, when adolescents were aged between 10 and 14 years, scale values of affiliation with drug-using peers and affiliation with deviant peers as well as dichotomous indicators of whether the adolescents were in a grade level lower than grade 6 (as an indicator of grade retention) or had any friends aged older than 15 years were all included in the model.24–26 We also included a scale of parent monitoring, in which higher scores indicate less monitoring, in the model.27 From year 9, dichotomous indicators of whether the adolescents were in a grade level lower than grade 9 or had any friends aged older than 17 years were included, as was a measure of parents’ highest level of educational attainment, a proxy for socioeconomic status.28 The difference between year 9 and year 6 scale values for drug-using peer affiliation, deviant peer affiliation, and parent monitoring were included in the final model. We also included gender and race as potential confounds that were collected at baseline.

To assess the possibility of additional selection effects, we conducted survival analysis to examine the age at first use of tobacco stratified by the year-10 work categories specified above. Because the proportionality assumption for this model was valid when adolescents who worked more than 10 hours were compared with a combined category of adolescents who did not work and who worked less than 10 hours, a Cox–proportional hazards regression model was used to empirically quantify the difference in the hazard function of smoking based on year-10 work status.

The final analytic step was to assess the incidence of tobacco use between years 10 and 11. Adolescents at risk for incident tobacco use were defined as never reporting tobacco use since the year-6 assessment through year 10. Incidence was then estimated across the entire sample at risk and then separately across 4 work transition categories: did not work in both years 10 and 11, did not work in year 10 but worked in year 11, worked in year 10 but did not work in year 11, and worked in both years. Relative risk estimates were calculated with adolescents not working in both years as the reference group.

RESULTS

Sample

Table 1 ▶ presents descriptive characteristics of the baseline and restricted samples (those interviewed in both years 10 and 11). Across all samples, close to 55% were male and 85% were African American. Of the total sample, a little more than half received free school lunch at the first grade (a proxy of socioeconomic status for adolescents).29 Complete information on baseline socioeconomic and intervention status were available on adolescents at year 11 and in the restricted sample, which reflects the follow-up strategy.

TABLE 1—

Descriptive Characteristics of Samples, by Year of Follow-Up: Second Generation of the Prevention and Intervention Research Center Study, Baltimore, Md, 1993–2004

| Baseline, No. (Category %) | Year 10, No. (Category %) | Year 11, No. (Category %) | Restricted Sample,a No. (Category %) | |

| Total | 799 (100.00) | 570 (100.00) | 515 (100.00) | 488 (100.00) |

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 435 (54.44) | 315 (55.26) | 283 (54.95) | 263 (53.89) |

| Female | 364 (45.56) | 255 (44.74) | 232 (45.05) | 225 (46.11) |

| Raceb | ||||

| African American | 678 (84.86) | 492 (86.32) | 452 (87.77) | 429 (87.91) |

| White | 120 (15.02) | 78 (13.68) | 63 (12.23) | 59 (12.09) |

| Proxy measures of socioeconomic status | ||||

| Not available | 6 (0.75) | 4 (0.70) | 5 (0.97) | 4 (0.82) |

| Received free school lunch | 411 (51.44) | 305 (53.51) | 317 (61.55) | 297 (60.86) |

| Received reduced-price school lunch | 52 (6.51) | 41 (7.19) | 40 (7.77) | 39 (7.99) |

| Paid by child | 209 (26.16) | 151 (26.49) | 153 (29.71) | 148 (30.33) |

| Missing | 121 (15.14) | 69 (12.11) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| Intervention status | ||||

| Control group | 261 (32.67) | 181 (31.75) | 169 (32.82) | 157 (32.17) |

| Classroom-centered group | 258 (32.29) | 182 (31.93) | 167 (32.43) | 163 (33.40) |

| Family–school partnership group | 260 (32.54) | 192 (33.68) | 179 (34.76) | 168 (34.43) |

| No design | 20 (2.50) | 15 (2.63) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| Year 10 follow-up characteristics | ||||

| Work status | ||||

| No work | 419 (73.51) | 361 (73.98) | ||

| 1–10 h/wk | 61 (10.70) | 54 (11.07) | ||

| > 10 h/wk | 90 (15.79) | 73 (14.96) | ||

| Current tobacco use | 74 (12.98) | 58 (11.89) | ||

| Year 11 follow-up characteristics | ||||

| Work status | ||||

| No work | 320 (62.14) | 300 (61.48) | ||

| 1–10 h/wk | 54 (10.49) | 52 (10.66) | ||

| > 10 h/wk | 141 (27.38) | 136 (27.87) | ||

| Current tobacco use | 89 (17.28) | 75 (15.37) | ||

aThe restricted sample included only those adolescents surveyed in both years 10 and 11.

bOne student was of Hispanic ethnicity at baseline and was lost to follow-up at years 10 and 11.

cThese students joined the classrooms during first grade.

The prevalence of work increased from year 10 to year 11. At year 10, 26% of the adolescents surveyed reported working for pay; by year 11, close to 40% worked for pay. There were no apparent differences between the distribution of work status among the separate year-10 or year-11 samples and the restricted sample of adolescents who were assessed in both years. Among those who worked in year 10, 30% were employed in fast-food restaurants and the remainder were employed babysitting (11%), working in restaurants (9%), working as a store clerk (12%), or in other occupations, including cosmetology and other retail (20%). By year 11, babysitting reduced to only 4%, although 30% of adolescents who worked still worked in fast food and the remainder worked at restaurants (12%), stores (15%), or in other occupations, such as construction, cosmetology, retail, service (i.e. catering, teaching dance, etc), and maintenance and cleaning jobs (24%; data on type of job not shown).

The prevalence of current tobacco use increased from approximately 13% at year 10 (which is similar to state-level estimates of public school–attending 10th graders in Mary-land) to 17% at year 11.30 Among the 488 adolescents assessed in both years, 50% did not work in both years, 25% did not work in year 10 but worked in year 11, and the remainder was roughly evenly distributed between working in year 10 but not in year 11 and working in both years (data not shown).

Cross-Sectional Analysis

Of the 570 adolescents assessed at year 10, complete information was available for 400 on the first-grade, sixth-year, and ninth-year variables used in the multivariable logistic regression model. Univariate associations between constructs included in the adjusted model and current tobacco use for these 400 adolescents are presented in Table 2 ▶ (estimates are qualitatively similar in univariate analyses that included all adolescents). These results showed that high-intensity workers at year 10 were 3 times more likely to report current use of tobacco than were nonworkers (odds ratio [OR]=2.93; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.40, 6.11), although there was not strong evidence to link moderate work with current use (OR = 1.38; 95% CI = 0.50, 3.83). There were additional positive associations in univariate analyses between current tobacco use and high levels of aggression in first grade, reductions in parent monitoring between years 6 and 9, affiliation with peers who used drugs in year 6, and increases in affiliations with peers who used drugs between years 6 and 9.

TABLE 2—

Prevalence for Categorical Variables and Logistic Regression Results, Tobacco Use at Year 10: Second Generation of the Prevention and Intervention Research Center Study, Baltimore, Md, 1993–2004 (N = 400)

| Current Tobacco | ||||

| No. | Prevalence, % | Usea OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Work status | ||||

| No work (Ref) | 299 | 8.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1–10 h/wk | 44 | 11.4 | 1.38 (0.50, 3.83) | 1.50 (0.46, 4.82) |

| > 10 h/wk | 61 | 21.3 | 2.93 (1.40, 6.11) | 1.98 (0.84, 4.67) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (Ref) | 215 | 11.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 185 | 9.7 | 0.82 (0.43, 1.55) | 1.04 (0.48, 2.22) |

| Race | ||||

| African American (Ref) | 352 | 9.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| White | 48 | 18.8 | 2.16 (0.96, 4.83) | 1.25 (0.43, 3.63) |

| Academic performance | ||||

| ≥ Grade 6 or above (year 6; Ref) | 366 | 11.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| < Grade 6 | 34 | 5.9 | 0.49 (0.11, 2.14) | 0.22 (0.04, 1.32) |

| ≥ Grade 9 or above (year 9; Ref) | 331 | 9.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| < Grade 9 | 69 | 17.4 | 2.04 (0.99, 4.20) | 2.07 (0.76, 5.63) |

| First grade behaviorsb | ||||

| Authority acceptance | . . .c | . . .c | 1.54 (1.08, 2.18) | 1.43 (0.94, 2.19) |

| Parent monitoring—year 6 | . . .c | . . .c | 1.02 (0.94, 1.10) | 0.98 (0.88, 1.11) |

| Change in parent monitoring—from year 6 to year 9 | . . .c | . . .c | 1.07 (1.00, 1.15) | 1.03 (0.95, 1.12) |

| Peer affiliationd | . . .c | . . .c | ||

| Peers who use drugs—year 6 | . . .c | . . .c | 1.11 (1.02, 1.21) | 1.23 (1.05, 1.44) |

| Change in peers who use drugs—from year 6 to year 9 | . . .c | . . .c | 1.14 (1.06, 1.22) | 1.18 (1.07, 1.31) |

| Deviant peers—year 6 | . . .c | . . .c | 1.07 (0.99, 1.16) | 1.01 (0.88, 1.16) |

| Change in deviant peers—from year 6 to year 9 | . . .c | . . .c | 1.03 (0.96, 1.10) | 0.99 (0.90, 1.10) |

| No peers aged older than 15 years—year 6 (Ref) | 198 | 9.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Peers aged older than 15 years—year 6 | 202 | 12.4 | 1.41 (0.74, 2.68) | 1.32 (0.62, 2.82) |

| No peers aged older than 17 years—year 9 (Ref) | 134 | 7.5 | 1.00 NA | 1.00 NA |

| Peers aged older than 17 years—year 9 | 266 | 12.4 | 1.76 (0.84, 3.68) | 1.08 (0.46, 2.53) |

| Parents’ educational attainment | ||||

| High school graduate (Ref) | 160 | 10 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Eighth grade or less | 5 | 60 | . . .e | . . .e |

| Some high school | 51 | 15.7 | 1.67 (0.67, 4.18) | 1.48 (0.51, 4.27) |

| Vocational/college/graduate | 184 | 8.7 | 0.86 (0.41, 1.77) | 0.92 (0.41, 2.07) |

Note. OR = odds ratio (crude); CI = confidence interval; AOR = adjusted odds ratio. All estimates were derived from respondents with no missing data and who were assessed at the 10th year of follow-up.

aCurrent tobacco use was defined as having used tobacco in the past 30 days.

bEarly childhood characteristics previously associated with adolescent tobacco use were incorporated into the logistic model. Teachers’ reports of adolescents’ early authority acceptance, an indicator of aggressive behaviors, as exhibited in the first grade were included in the model. A scale of parent monitoring, in which higher scores indicate less monitoring, was also included in the model.

cContinuous variables; OR represents change per unit.

dFrom year 6, when adolescents were aged between 10 and 14 years, scale values of affiliation with drug-using peers and affiliation with deviant peers as well as dichotomous indicators of whether the adolescents were in a grade level lower than grade 6 (as an indicator of grade retention) or had any friends aged older than 15 years were all included in the model.24–26 From year 9, dichotomous indicators of whether the adolescents were in a grade level lower than grade 9 or had any friends aged older than 17 years were included.

eSmall sample sizes impeded ability to calculate estimates.

Constructs that have been previously associated with substance-using behaviors were entered into the logistic model to assess for a potential selection effect. Estimates from the multivariable model (also presented in Table 2 ▶) revealed that after including these variables, the relationship between high work intensity and current tobacco use was somewhat attenuated and the corresponding CI now included the null value (adjusted OR [AOR] = 1.98; 95% CI = 0.84, 4.67). Further analyses revealed that 1 construct was largely responsible for attenuating the relationship between high work intensity and tobacco use: changes in drug-using peers between years 6 and 9, which itself remained linked with current use of tobacco (AOR = 1.18; 95% CI = 1.07, 1.31). The only other variable in the multivariable model that remained linked with current use of tobacco was affiliation with drug-using peers in year 6 (AOR = 1.23; 95% CI = 1.05, 1.44).

Age of First Tobacco Use

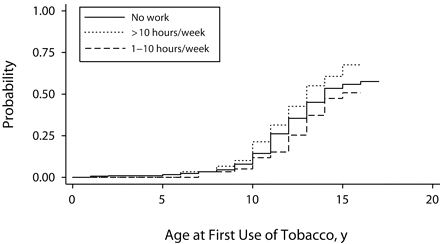

Kaplan–Meier (product–limit) estimates for age of first use of tobacco by 10th-year work intensity are presented in Figure 1 ▶. Aside from a few sparse respondents who initiated tobacco use earlier than age 7 years, the earliest tobacco users initiated use at age 7 years. The median failure time (age of first use) among adolescents who worked more than 10 hours at year 10 was at age 13 years. Nonworkers at year 10 had a median failure time at age 14 years, whereas moderate workers had a median failure time at age 15 years. Estimates from a Cox–proportional hazards model indicated an increased hazard ratio for high-intensity workers compared with a collapsed category of moderate-intensity workers and nonworkers (hazards ratio = 1.34; 95% CI = 1.01, 1.78).

FIGURE 1—

Kaplan–Meier failure estimates of age of first use of tobacco, by year-10 work intensity: Prevention and Intervention Research Center Study, Baltimore, Md, 1993–2004

Longitudinal Analysis

The incidence of tobacco use between years 10 and 11 across the entire sample and the 4 work transition categories is presented in Table 3 ▶. A total of 488 adolescents were surveyed in both the 10th and 11th year of follow-up. Of these, 214 had not yet reported using tobacco at year 10. Overall, the 1-year incidence of tobacco use in this “at risk” sample was 14%. However, there were significant differences in the incidence of tobacco use across the work-transition categories. Incidence of smoking was 0.29 among adolescents who did not work in year 10 but did work in year 11 versus 0.04 among the adolescents who did not work in both periods (relative risk=8.0; 95% CI=2.8, 22.9). In addition, the incidence of tobacco use among adolescents who worked in both periods was 0.31, which yielded a relative risk of 8.7 (95% CI=2.9, 15.8) compared with non-workers. Although both relative risk estimates have corresponding 95% CIs that are wide, the lower bounds for both are far from the null, which signals strong evidence of an elevated risk.

TABLE 3—

Incident Tobacco Use Between Years 10 and 11: Second Generation of the Prevention and Intervention Research Center Study, Baltimore, Md, 1993–2004

| Ever Use | At Risk | Event | Incidence | RR (95% CI) |

| Total | 214 | 31 | 0.14 | |

| No work in both years (Ref) | 111 | 4 | 0.04 | 1.00 |

| No work to work | 52 | 15 | 0.29 | 8.00 (2.79, 22.93) |

| Work to no work | 19 | 2 | 0.11 | 2.92 (0.57, 14.85) |

| Work both periods | 32 | 10 | 0.31 | 8.67 (2.91, 15.81) |

Note. RR = relative risk; CI = confidence interval. We assessed the incidence of tobacco use between years 10 and 11. Adolescents at risk for incident tobacco use were defined as never reporting tobacco use since the year-6 assessment through year 10. Incidence was then estimated across the entire sample at risk and then separately across 4 work transition categories: did not work in both years 10 and 11, did not work in year 10 but worked in year 11, worked in year 10 but did not work in year 11, and worked in both years. Relative risk estimates were calculated with adolescents not working in both years as the reference group.

DISCUSSION

The results from this study indicated a clear relationship between working for pay and adolescent tobacco use. It is noteworthy that this association held among adolescents in a primarily urban environment. Previous research indicated that adolescents who find jobs in urban areas are unique because they have found work where jobs are likely scarce.14,15,31 They also may be more likely to work to pay for transportation and supplemental school materials.15,32 However, we found that the time adolescents report working for pay during the school year was positively associated with the likelihood of current tobacco use. Thus, it appears that the relationship between work and tobacco use seen previously in both nationally representative and community surveys of more-affluent adolescents exists even in urban areas.

Evidence of a selection effect is supported by these analyses, which indicate that the cross-sectional relationship between work hours and tobacco use was somewhat attenuated in models in which we controlled for a number of earlier childhood predictors of adolescent substance use. However, because work information was not collected until year 10 and changes in drug-using peers between years 6 and 9 largely drove this attenuation, these results should be interpreted cautiously. We can not exclude the possibility that a young person started working between years 6 and 9 and developed friendships with coworkers who used drugs, which would clearly implicate working as a risk factor versus a potential selection effect. On the other hand, survival analysis indicates that adolescents who worked more than 10 hours per week at year 10 did tend to report earlier ages of tobacco use initiation. To explain similar results, Newcomb and Bentler proposed a theory of “precocious development”—a developmental trajectory in which adolescents seek out the rewarding aspects of adulthood ahead of their counterparts by assuming social roles (e.g., worker) and adult-like behaviors (e.g., tobacco use), although further longitudinal research is needed to discern such a trajectory.16

The Kaplan–Meier curves indicated that moderate-intensity workers tended to initiate tobacco use later than did both nonworkers and high-intensity workers. This is similar to findings from the Monitoring the Future study, in which a greater share of nonworkers reported using tobacco heavily, marijuana, and cocaine than did adolescents who worked between 1 and 10 hours per week.5 This suggests that perhaps a moderate amount of work is protective against smoking and other drug involvement among adolescents. However, more research is needed to examine the benefits to adolescents of work and to investigate the threshold that differentiates “high” work intensity from “moderate” work intensity.

The most striking finding of this research concerns the incidence of tobacco use between the 10th and 11th years of follow-up. Among adolescents who had not yet used tobacco, those who worked during 2 consecutive years as well as those who started to work between these years were at least 3 times more likely to report tobacco use initiation compared with nonworkers. These findings suggest that working has some impact on adolescent tobacco use independent of selection effects. Young workers may resort to cigarette use in order to take breaks from the duties and tasks they are required to perform at work, because they have access to commercial sources of cigarettes vis-à-vis their job earnings, or to cope with the stresses of balancing the responsibilities of being a student and a worker. Further research of this sample, and of others that contain more-detailed information on the types and characteristics of the jobs adolescents hold, will help test these and other hypotheses.

Our study consisted largely of African American adolescents, and much research has been devoted to smoking behaviors among this group. In general, African American adolescents are less likely to report smoking compared with White adolescents.33–35 Proposed reasons for this vary, ranging from a reduced likelihood of developing patterns of habitual or daily use, stronger bonds to religious organizations, higher levels of parental disapproval of smoking, or a reduced likelihood of positive smoking-related attitudes compared with White adolescents.36–40 Informal social controls, such as bonds with religious entities and familial bonds that protected adolescents from substance use in the past might weaken when adolescents start working and thereby increase substance-using behaviors.41,42 In addition, the role of cigarette breaks and increased exposure to coworkers who smoke may promote more positive smoking-related attitudes. Future research on these topics is crucial for persons interested in using the work-place as a venue for adolescent tobacco prevention programs.

Strengths and Limitations

There are 2 significant limitations of this study. In the 10th and 11th years of follow-up, adolescents were asked only limited information about their work experiences. Other work-related constructs, such as work duration or work schedules, also likely impact young workers’ tobacco use, but were not ascertained in these surveys. Additional information about adolescents’ work experiences has been collected in year 12, although these data are not yet available for analysis. The other significant limitation is temporal sequencing. Although our longitudinal study assessed adolescents annually, if adolescents moved from not working to working between the year-10 and year-11 assessments and also initiated tobacco use between these 2 surveys, it is unclear whether working preceded smoking or vice versa. Finally, potentially important confounders associated with adolescents smoking in the past, such as discretionary income and parental smoking behaviors, are not included in the survey or analysis.

Our study carries with it strengths that offset these limitations. First, the cohort of adolescents came from a well-defined population of adolescents who entered first grade classrooms in a specific geographic region, thereby reducing biases inherent in convenience or other sampling procedures. The strengths of the longitudinal structure were exploited to control for childhood constructs assessed prospectively and, thus, less subject to recall bias, including measures of first-grade aggression and age at first use of tobacco. The longitudinal design also allowed us to look at incident tobacco-using behaviors specific to general work transition categories, which to our knowledge, have never been performed elsewhere. Finally, the sample was an urban-based community cohort of primarily African American youth. Research on work in this population is limited, and our study lends evidence to the notion that the link between working and tobacco is generalizable to settings of varying economic conditions.

Conclusions

We recommend 3 public health responses to these findings. First, given that young workers in this study and in most other studies are concentrated among certain industries (such as fast food, other restaurant work, and retail), efforts should be made to encourage these industries be smoke-free. Previous research has indicated that totally smoke-free workplaces are associated with reductions in prevalence of smoking, and we believe that these policies might also lead to reduced smoking incidence among young people.43 Second, efforts should be made to establish workplace-based prevention programs. These programs would ideally incorporate prevention strategies pertinent to young workers, such as fiscal management and ways to cope with stress while at work. Finally, this research should highlight the need for future studies to more carefully and systematically evaluate the impact that working for pay has on the substance-using behaviors of adolescents.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA018013 and DA11796) and from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH57005).

Human Participant Protection This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health institutional review board.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors R. Ramchand originated and performed all analyses and led the writing. N. S. Ialongo was the principal investigator of the larger cohort study and contributed to the writing and analyses. H. D. Chilcoat also contributed to the writing and analyses. All authors helped to conceptualize ideas, interpret findings, and review drafts of the article.

References

- 1.Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

- 2.Grunbaum JA, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2003. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2004;53:1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette use among high school students—United States, 1991–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004; 53:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278:823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachman JG, Schulenberg J. How part-time work intensity relates to drug use, problem behavior, time use, and satisfaction among high school seniors: are these consequences or merely correlates. Dev Psychol. 1993;29:220–235. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valois RF, Dunham AC, Jackson KL, Waller J. Association between employment and substance abuse behaviors among public high school adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25:256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safron DJ, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG. Part-time work and hurried adolescence: the links among work intensity, social activities, health behaviors, and substance use. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42:425–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu LT, Schlenger WE, Galvin DM. The relationship between employment and substance use among students aged 12 to 17. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32:5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinberg LD, Fegley S, Dornbusch SM. Negative impact of part-time work on adolescent adjustment: evidence from a longitudinal study. Dev Psychol. 1993; 29:171–180. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paternoster R, Bushway S, Brame R, Apel R. The effect of teenage employment on delinquency and problem behaviors. Soc Forces. 2003;82:297–335. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner L, Mermelstein R, Flay B. Individual and contextual influences on adolescent smoking. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:175–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Light A. High School Employment. In: Bureau of Labor Statistics, ed. National Longitudinal Survey Discussion Paper, report NLS 95-27. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor; 1995.

- 13.Board on Children, Youth and Families. Protecting Youth at Work: Health, Safety, and Development of Working Children and Adolescents in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. [PubMed]

- 14.Mortimer JT. Working and Growing Up in America. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 2003.

- 15.Newman KS. No Shame in My Game: The Working Poor in the Inner City. 1st ed. New York, NY: Knopf and the Russell Sage Foundation; 1999.

- 16.Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Consequences of Adolescent Drug Use: Impact on the Lives of Young Adults. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1988.

- 17.Staff J, Uggen C. The fruits of good work: early work experiences and adolescent deviance. J Res Crime Delinquency. 2003;40:263–290. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachman JG, Safron DJ, Sy SR, Schulenberg JE. Wishing to work: new perspectives on how adolescents’ part-time work intensity is linked to educational disengagement, substance use, and other problem behaviors. Intl J Behav Dev. 2003;27:301–315. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Storr CL, Ialongo NS, Kellam SG, Anthony JC. A randomized controlled trial of two primary school intervention strategies to prevent early onset tobacco smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furr-Holden CD, Ialongo NS, Anthony JC, Petras H, Kellam SG. Developmentally inspired drug prevention: middle school outcomes in a school-based randomized prevention trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73:149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ialongo NS, Werthamer L, Kellam SG, Brown CH, Wang S, Lin Y. Proximal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on the early risk behaviors for later substance abuse, depression, and antisocial behavior. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27:599–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambert SF, Brown TL, Phillips CM, Ialongo NS. The relationship between perceptions of neighborhood characteristics and substance use among urban African American adolescents. Am J Community Psychol. 2004; 34:205–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellam S, Ialongo N, Brown H, et al. Attention problems in first grade and shy and aggressive behaviors as antecedents to later heavy or inhibited substance use. NIDA Res Monogr. 1989;95:368–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kandel D. Adolescent marihuana use: role of parents and peers. Science. 1973;181:1067–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lloyd JJ, Anthony JC. Hanging out with the wrong crowd: how much difference can parents make in an urban environment? J Urban Health. 2003;80:383–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bryant AL, Schulenberg J, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Understanding the links among school misbehavior, academic achievement, and cigarette use: a national panel study of adolescents. Prev Sci. 2000;1:71–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chilcoat HD, Dishion TJ, Anthony JC. Parent monitoring and the incidence of drug sampling in urban elementary school children. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miech RA, Hauser RM. Socioeconomic status and health at midlife. A comparison of educational attainment with occupation-based indicators. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11:75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ensminger ME, Forrest CB, Riley AW, et al. The validity of measures of socioeconomic status of adolescents. J Adolesc Res. 2000;15:392–419. [Google Scholar]

- 30.2002 Maryland Adolescent Survey. Baltimore: Maryland State Department of Education; 2003.

- 31.Wilson WJ. When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor. 1st ed. New York, NY: Knopf; 1996.

- 32.Entwisle DR, Alexander KL, Olson LS. Early work histories of urban youth. Am Sociol Rev. 2000;64:279–297. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2005, Volume 1: Secondary School Students. Bethesda, Md: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2006. NIH publication 06-5883.

- 34.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results From the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, Md: Office of Applied Studies; 2004. NSDUH series H-28; DHHS publication SMA 05-4062.

- 35.Wallace JM Jr, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Cooper SM, Johnston LD. Gender and ethnic differences in smoking, drinking and illicit drug use among American 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students, 1976–2000. Addiction. 2003;98:225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellickson PL, Orlando M, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. From adolescence to young adulthood: racial/ethnic disparities in smoking. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griesler PC, Kandel DB. Ethnic differences in correlates of adolescent cigarette smoking. J Adolesc Health. 1998;23:167–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Catalano R, Morrison DM, Wells EA, Gillmore MR, Iritani B, Hawkins JD. Ethnic differences in family factors related to early drug initiation. J Stud Alcohol. 1992;53:208–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clark PI, Scarisbrick-Hauser A, Gautam SP, Wirk SJ. Anti-tobacco socialization in homes of African-American and white parents, and smoking and non-smoking parents. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24:329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sussman S, Dent CW, Flay BR, Hansen WB, Johnson CA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Psychosocial predictors of cigarette smoking onset by White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian adolescents in Southern California. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 1987;36(suppl 4):11S–16S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirschi T. Crime and the family. In: Wilson J, ed. Crime and Public Policy. San Francisco, Calif: Institute for Contemporary Studies; 1983:53–68.

- 42.McMorris BJ, Uggen C. Alcohol and employment in the transition to adulthood. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41:276–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Effect of smoke-free workplaces on smoking behaviour: systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]