Abstract

Objectives. We examined the links between peer rejection and verbal abuse by a teacher during childhood with the early onset of sexual intercourse and the mediating role of delinquent behavior and low self-esteem in this context.

Methods. We assessed 312 students (159 girls) in northwestern Quebec annually from kindergarten through seventh grade. Peer identifications were used to assess peer rejection and verbal abuse by teachers from kindergarten through fourth grade. In seventh grade, self-reports were used to assess delinquent behavior, self-esteem, and having sexual intercourse. Multiple sources were used to assess control variables.

Results. Multiple imputation-based linear and logistic regressions showed that peer rejection was indirectly associated with a higher risk of early intercourse by its link with lower self-esteem, but only for girls. Verbal abuse by teachers during childhood was directly associated with a higher risk of early sexual intercourse and indirectly by its link with delinquent behavior.

Conclusions. The results underline the importance of both peers and teachers in healthy sexual development among youths, especially for girls, and emphasize the need for targeted health and sexual education programs.

Although sexual intercourse is a normative event during adolescence,1 the early onset of first intercourse may entail a variety of health-related adjustment problems, especially for girls. Girls who have their first sexual intercourse between the ages of 10 and 14 years have a greater number of sexual partners and a greater probability of having sex with high-risk partners compared with other girls, thus increasing the risk of adolescent pregnancy and of contracting sexually transmitted diseases.2

However, the comprehension of the predictors of the early onset of sexual intercourse has often been hampered by a lack of adequate data. Few longitudinal studies exist, and many of them rely on the retrospective recollection of the age of first intercourse and associated risk factors. Moreover, although sexual behavior is likely determined by multiple domains of influence,3 studies have usually focused on only 1 or 2 domains of influence. The main goal of this study was to examine the longitudinal links, including biological, psychological, and social factors, between problematic experiences in the school milieu (i.e., with peers and teachers) during childhood and the early onset of sexual intercourse.

According to general problem-behavior theory,4,5 the early initiation of sexual intercourse is one of a variety of problem behaviors in adolescence that result from common underlying antecedents. In addition to family factors, rejection by the peer group is among the most frequently evoked social antecedents of problem behavior.6 Evidence also suggests that peer rejection is associated with potentially risky sexual behavior among adolescents, namely, having oral sex with multiple partners.7 It is unclear, however, whether peer rejection during childhood also puts youths at risk of premature sexual intercourse in early adolescence.

A related question stems from the fact that children’s negative social experiences in school are not limited to rejection from the peer group. Teachers also exert a major influence on children’s developmental adjustment,8 and children who experience frequent verbal abuse by teachers are at significant risk for later behavioral adjustment problems.9 It is possible that negative school-related experiences, in the relationship both with peers and with teachers, may put youngsters on the track not only toward general delinquency but also toward risky sexual behavior such as having early sexual intercourse.

The first goal of our study was to examine potential predictive links from peer rejection and verbal abuse by teachers during childhood to the early onset of sexual intercourse.

The second goal of our study was to investigate the potential mechanism that might explain any predictive links from peer rejection and verbal abuse by teachers to the early onset of sexual intercourse. General problem-behavior theory4,5 suggests that problematic social experiences with peers and teachers should increase the risk of early onset of intercourse by their impact on generalized delinquency. In line with this notion, there is evidence for a predictive association between general delinquency and the early onset of sexual intercourse.10

There is, however, another possible pathway that might explain a predictive link—especially from peer rejection—to the early onset of sexual intercourse. Specifically, peer rejection has been shown to predict not only delinquent behavior but also low self-esteem.6 Sexual activity may thus serve as a coping mechanism, that is, as a way for adolescents to feel better about themselves. This compensation model of early intercourse is based on findings that many adolescents associate having sexual relations with high status and popularity among peers.7

Although prospective data have been reported in only 1 study so far, there is evidence that low self-esteem predicts early sexual intercourse among girls aged 12 to 14 years but not among boys.11 Early sexual intercourse may occur as a coping strategy in response to peer rejection and subsequent low self-esteem, but a similar coping process may also occur as a result of verbal abuse by teachers.

We sought to examine the predictive links of peer rejection and verbal abuse by teachers during childhood to the early onset of sexual intercourse and whether these links would be mediated by students exhibiting generally delinquent behavior or having low self-esteem. We examined these associations after we controlled for early deviant characteristics during childhood and for pubertal status, which is an important predictor of sexual intercourse among both girls and boys.12,13 We also examined whether these links differed for boys and girls.

METHODS

Sample

Participants were part of a sample of 399 White French-speaking children (177 girls) from all (i.e., 5) primary schools in a small Canadian community in northwestern Quebec. The children were first assessed in kindergarten (mean age = 6.01 years, SD = 0.28) in 1987. All kindergarten children in the community were targeted for participation, and 95.3% of the children participated in the study. Data collection for the outcome in seventh grade was done in 1994.

In each of the 5 schools, there were about 3 classrooms per grade. Classroom composition changed each year in the participating schools. Children attended primary school through sixth grade and then entered high school. All participants attended the same high school, which is the only high school in the community.

The children’s average socioeconomic status was very similar to the provincial average. Twenty-two percent of the participants assessed in kindergarten were lost from the study by the age of 13 years. The final sample for the analyses comprised 312 participants (159 girls; 50.96%). Those lost through attrition were more often verbally abused by a teacher, were less accepted by peers, and had higher scores on the antisocial behavior index (described in the “Measures” section) in kindergarten compared with participants who remained in the study.

Measures

Verbal abuse by teachers.

Verbal abuse was assessed in kindergarten through fourth grade through the peer identification of students who had suffered such abuse, a similar strategy to the one used by Olweus (Olweus D, University of Norway, Bergen, unpublished manuscript 1996). The verbal abuse measure shows good criterion-related validity as indicated by a significant relation to teacher-rated disruptiveness and attention problems in kindergarten.9

Booklets of photographs (for kindergarten and first grade) or names (second grade and older) of all the children in a given class were handed out to the participants. Children were then asked to circle the photos (or names) of up to 3 children “who always get picked on by the teacher.” Picked on was defined as being scolded, being criticized, or being shouted at. For each year, we calculated the total number of received nominations for each participant and z standardized them within the classroom. The stability of the verbal abuse measure over a 1-year period was moderate to high,15 with r values of 0.37 to 0.52. We created an average verbal abuse score for each participant by averaging the individual item scores across the covered 5-year period.

Peer rejection

We assessed peer rejection in kindergarten through fourth grade through peer nominations following the criteria outlined by Coie et al.16 The children were asked to circle the photos (or names) of up to 3 children they most liked to play with (i.e., positive identifications) and of up to 3 children they least liked to play with (i.e., negative identifications). For each year, we calculated the total number of received positive identifications for each participant and z standardized them within the classroom to create a total liked-most score. We calculated the total number of received negative identifications for each participant and z standardized them within the classroom to create a total liked-least score. The liked-least score was then subtracted from the liked-most score to create a social preference score, which was again z standardized within the classroom.

The stability of social preference over a 1-year period ranged from r = 0.47 to r = 0.57. An average social preference score was created for each participant by averaging the individual item scores across the covered 5-year period. The social preference score was then multiplied by −1, such that higher values indicated a higher level of peer rejection.

Antisocial behavior.

We measured antisocial behavior from kindergarten through fourth grade using peer nomination. We used 2 questions inspired by the Preschool Behavior Questionnaire.17 Children were asked to circle the photos or names of up to 3 classmates who best fit 2 behavioral descriptions (“gets into a lot of fights” and “disturbs the class”). For each child, we calculated the total number of received nominations for each item and z standardized them within the classroom.

Delinquent behavior.

We assessed delinquent behavior in seventh grade using the Self-Reported Delinquent Behavior Questionnaire.18 The 25 questions addressed fighting, theft, vandalism, and drug and alcohol use over the past 12 months. Participants answered whether they had never, rarely, sometimes, or often (scored 1–4 respectively) engaged in each act. We created a continuous total delinquent behavior scale by summing the individual item scores, with Cronbach’s α = .91.

Self-esteem.

We assessed participants’ self-esteem in seventh grade with the Self-Perception Profile for Children,19 which assessed self-esteem as well as domain-specific self-perceptions. Each scale of this profile comprised 6 items, which are scored from 1 through 4, with higher scores reflecting more-positive self-perceptions. We created a continuous total self-esteem score for each participant by averaging the respective item scores, with Cronbach’s α = .83.

Early sexual intercourse.

In seventh grade, that is, at the age of 13 years, participants were asked whether they had already had complete sexual intercourse (i.e., with penetration). In line with previous findings,20 53 (17%) respondents indicated having had complete sexual intercourse. Of these, 28 (or 53%) were boys and 25 (or 47%) were girls (χ2[1] = 0.37, not significant).

Pubertal status.

In seventh grade, we assessed pubertal status using the Pubertal Development Scale.21 Participants rated their physical development on a 4-point scale (1 = “no development,” 2 = “development has barely begun,” 3 = “development has definitely begun,” and 4 = “development is complete”) on each of several characteristics, including growth spurt in height, pubic hair, and skin change for both boys and girls; facial hair growth and voice change in boys only; and breast development and menarche in girls only. We then used responses to classify participants into 5 categories according to Tanner’s22 pubertal development stages: 1=prepubertal, 2=early pubertal, 3= midpubertal, 4=late pubertal, and 5= postpubertal.21 Zero-order correlations, means, and standard deviations of all study variables are depicted in Table 1 ▶.

TABLE 1—

Zero-Order Correlations and Means of Scores and Standard Deviations of All Variables: Northwestern Quebec, 1987–1994

| Gender | Pubertal Status | Antisocial Behavior | Peer Rejection | Verbal Abuse by Teacher | Delinquent Behavior | Self- Esteem | Sexual Intercourse | Scores on Scales, Mean (SD) TQ1 | |

| Gender | 1.00 | 0.49 (0.50) | |||||||

| Pubertal status | −0.63† | 1.00 | 3.36 (0.76) | ||||||

| Antisocial behavior | 0.43† | −0.27† | 1.00 | −0.13 (0.49) | |||||

| Peer rejection | 0.13** | 0.08 | 0.41† | 1.00 | −0.18 (0.69) | ||||

| Verbal abuse by teacher | 0.32† | −0.22† | 0.76† | 0.31† | 1.00 | 0.50 (0.57) | |||

| Delinquent behavior | 0.18*** | 0.03 | 0.17*** | 0.05 | 0.23† | 1.00 | 29.99 (5.97) | ||

| Self-esteem | 0.08 | −0.11* | 0.01 | −0.15** | 0.02 | −0.27† | 1.00 | 3.13 (0.61) | |

| Sexual intercourse | 0.03 | 0.18*** | 0.12* | 0.07 | 0.20*** | 0.43† | −0.16** | 1.00 | 0.17 (0.38) |

Note. Gender is coded such that 0 = girls and 1 = boys; early intercourse is coded such that 0 = no sexual intercourse and 1 = completed sexual intercourse. Antisocial behavior and peer rejection were assessed in kindergarten through fourth grade. Delinquent behavior, self-esteem, and sexual intercourse were assessed in seventh grade. Verbal abuse by the teacher was assessed each year (kindergarten through seventh grade) For details on how each variable was assessed, see “Methods” section.

*P < .10; **P < .05; ***P < .01; †P < .001; 2-tailed tests.

Procedures

Peer identifications as well as self-reported assessments were conducted in the classrooms between April and May at the end of each school year. Trained research assistants administered and collected the questionnaires, but students completed the questionnaires at their respective desks in private.

For both the primary school and the high school data collections, teachers were asked to leave the room during the assessment to emphasize the fact that students’ responses were kept confidential and would not be revealed to others. The students were encouraged to keep their answers confidential and not to talk with others about their answers.

RESULTS

We used SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) to perform linear and logistic regression analyses to examine (1) to what extent peer rejection and verbal abuse by a teacher in middle childhood would be related to the early onset of sexual intercourse (after we controlled for gender, childhood antisocial behavior, and pubertal status at the age of 13 years) and (2) whether these relations would be mediated by individuals’ delinquent behavior or self-esteem.

Analyses were conducted with multiple imputations of missing data, such that adolescents who participated in the data collection when aged 13 years were included in the analyses even if they had some missing responses with respect to variables collected earlier. The results from a sample in which missing data were not estimated yielded similar results.

To show a mediational process, the following conditions must be met: (1) the predictor must predict the criterion, (2) the predictor must predict the mediator variable, (3) the mediator variable must predict the criterion, and (4) the predictive effect of the predictor variable on the criterion must be nonsignificant and estimated at zero once the mediator variable is included in the model equation.23

To examine whether these conditions were met, we first conducted 2 hierarchical linear regressions to test the effects from the main predictors and control variables (i.e., gender, pubertal status, childhood antisocial behavior, childhood peer rejection, and childhood verbal abuse by the teacher) to the putative mediators (i.e., delinquent behavior and self-esteem in early adolescence). At step 2 of each of the 2 regression analyses, we introduced interaction terms to examine whether the links of peer rejection and verbal abuse by the teacher with delinquent behavior and self-esteem in early adolescence, respectively, were the same for boys and girls.

To facilitate interpretation, we z standardized all dependent and continuous independent variables before creating the interaction terms with gender, and we used the z-standardized variables in the regression analyses.24

The results from these analyses are presented in Table 2 ▶. As can be seen, after we controlled for the effect of gender (β = 0.50, P < .01) and pubertal status (β = 0.24, P < .01), verbal abuse by the teacher—but not peer rejection—was significantly related to delinquent behavior (β = 0.24, P < .05). Conversely, peer rejection—but not verbal abuse by the teacher—was significantly related to self-esteem (β = −0.15, P < .05).

TABLE 2—

Multiple Linear Regressions Predicting Delinquent Behavior and Self-Esteem in Early Adolescence: Northwestern Quebec, 1987–1994

| Predictor | B | t | F (df) | R2 |

| Prediction of delinquent behavior | 5.47 (6) | .20 | ||

| Gender | 0.50*** | 3.25 | ||

| Pubertal status | 0.24*** | 3.46 | ||

| Antisocial behavior | 0.04 | 0.37 | ||

| Peer rejection | 0.02 | 0.29 | ||

| Verbal abuse by teacher | 0.24** | 2.77 | ||

| Prediction of self-esteem | 1.72 (6) | .22 | ||

| Gender | 0.06 | 0.39 | ||

| Pubertal status | 0.10 | 1.34 | ||

| Antisocial behavior | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||

| Peer rejection | −0.15** | 2.36 | ||

| Verbal abuse by teacher | 0.03 | 0.29 |

Note. Gender is coded such that 0 = girls and 1 = boys. For details on how each variable was assessed, see “Methods” section.

**P < .05; ***P < .01; 2-tailed tests.

Next, we performed a hierarchical logistic regression to test the direct effects from the main predictor and control variables (i.e., gender, pubertal status, childhood antisocial behavior, childhood peer rejection, and childhood verbal abuse by the teacher) to the outcome (i.e., the early onset of sexual intercourse) without (step 1) and with the putative mediators in the model (step 2).

We included interaction terms involving gender in step 3 to examine whether peer rejection, verbal abuse by the teacher, and the 2 putative mediator variables affected the outcome significantly differently in boys and girls.

The results, presented in Table 3 ▶, showed that boys and physically more-mature individuals were more likely to have had early sexual intercourse (odds ratio [OR]=3.08, P<.05; and OR=2.95, P<.001, respectively). Youths who were more frequently verbally abused by their teachers were also more likely to have engaged in early sexual intercourse (OR = 1.99, P < .01), but peer rejection had no main effect on the early onset of sexual intercourse.

TABLE 3—

Logistic Regression Predicting the Odds of Early Intercourse: Northwestern Quebec, 1987–1994

| Change in F (df) | Change in R2 | Odds Ratio | t | |

| Step 1 | 16.61 (6) | 0.04† | . . . | . . . |

| Gender | . . . | . . . | 3.08** | 2.44 |

| Pubertal status | . . . | . . . | 2.95† | 4.42 |

| Antisocial behavior | . . . | . . . | 0.79 | 0.94 |

| Peer rejection | . . . | . . . | 0.94 | 0.33 |

| Verbal abuse by teacher | . . . | . . . | 1.99*** | 2.88 |

| Step 2 | 11.83 (2) | 0.07† | . . . | . . . |

| Delinquent behavior | . . . | . . . | 2.54† | 4.01 |

| Self-esteem | . . . | . . . | 0.80 | 1.08 |

| Step 3a | 8.66 (1) | 0.02*** | . . . | . . . |

| Interaction: Delinquent behavior × gender | . . . | . . . | 0.33** | 2.45 |

| Step 3b | 7.29 (1) | 0.02*** | . . . | . . . |

| Interaction: Self-esteem × gender | . . . | . . . | 2.58** | 2.16 |

Note. Instead of the χ2 statistic provided in standard logistic regression, the SAS procedure Proc MIANALYZE provides an F test as a multivariate inference for all the predictors of the multiple logistic regression. As in linear regression, the F statistic indicates whether the averaged explained variance is significant. Gender is coded such that 0 = girls and 1 = boys. The no–sexual intercourse group served as the comparison group for model tests and odds ratios. Only significant interaction terms are shown. For details on how each variable was assessed, see “Methods” section.

**P < .05; ***P < .01; †P < .001. All were 2-tailed tests.

The results from the second step showed that both putative mediators (i.e., delinquent behavior and self-esteem in early adolescence) were related to the early onset of sexual intercourse, but significant interaction terms in the third step showed that these associations varied across gender. The breakdown of the interactions indicated that the positive link between delinquent behavior and early sexual intercourse was significant for both genders but was stronger for girls (OR = 5.09, P < .001) than for boys (OR = 1.75, P < .05). The link between self-esteem and early sexual intercourse was significant and negative for girls (OR = 0.55, P < .05) but positive—albeit non-significant—for boys (OR = 1.31, P = .59).

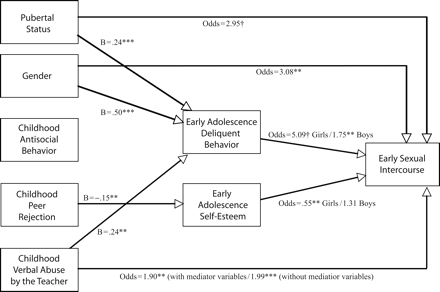

The combined results from the linear and logistic regression analyses are depicted in Figure 1 ▶. The combined findings suggest that verbal abuse by the teacher is directly associated with early sexual intercourse, as well as indirectly by delinquent behavior, especially for girls. However, the direct effect of verbal abuse by the teacher on early sexual intercourse in step 2 of the logistic regression (OR = 1.90, P < .05) was very similar to the effect obtained in the first step without the putative mediator variables (OR = 1.99, P < .01). This indicates that the predictive link from verbal abuse by the teacher to early sexual intercourse was not mediated by delinquent behavior.

FIGURE 1—

Graphical depiction of the combined results from the linear regressions predicting the putative mediator variables (delinquent behavior and self-esteem) and from the logistic regression predicting early sexual intercourse: Northwestern Quebec, 1987–1994.

Note. See “Methods” section for details of how variables were assessed. **P < .05; ***P < .01; †P < .001.

For peer rejection, the combined results suggest an indirect association with early sexual intercourse by low self-esteem, albeit only for girls. However, low self-esteem did not play a true mediating role in this context, because peer rejection had not shown an initial direct link with early sexual intercourse.

DISCUSSION

We sought to examine the predictive links of peer rejection and verbal abuse by the teacher during childhood to the early onset of sexual intercourse and the potential mediating role of general delinquency or low self-esteem in this context. After we controlled for gender, early deviant characteristics during childhood, and pubertal status, we found that verbal abuse by the teacher during childhood predicted the early onset of sexual intercourse.

At least part of this link was indirect by an association with delinquent behavior in early adolescence, which in turn was related to a higher risk of early sexual intercourse. Rejection by valued socializing agents such as teachers might lower children’s motivation to conform to the conventional and nondeviant expectations put forth by these agents.25 Instead, these children are increasingly likely to adopt deviant behaviors and to affiliate with others who reinforce these behaviors, thus affording ample opportunity to engage in nonnormative activities, including early-onset sexual intercourse.12 Our finding that deviant behavior was an especially strong predictor of girls’ compared with boys’ early onset of sexual intercourse may be explained by girls’ greater vulnerability to being pressured into sexual relations by their equally deviant partners.

Disengagement from normative behavior alone, however, cannot account for the predictive link between verbal abuse by the teacher and the early onset of sexual intercourse. Indeed, verbal abuse by the teacher retained a direct association with early intercourse even when delinquent behavior was included in the model. Other unmeasured potential mediator variables may account for this link (e.g., a decrease in academic interest and achievement motivation, which have both been linked to both verbal abuse by the teacher and the onset of sexual intercourse in adolescents).20,26

Rejection by the peer group in childhood was also—at least indirectly—associated with the early onset of sexual intercourse. Specifically, peer rejection was related to low self-esteem, which in turn was related to an increased risk of early sexual intercourse among girls. Among boys, it was high rather than low self-esteem that was related to the early onset of sexual intercourse, although this latter finding did not reach statistical significance. The finding of an association between low self-esteem and early sexual intercourse for girls but not for boys is concordant with previous research.11

As suggested by Spencer et al.,11 this gender difference may be because of a societal double standard whereby early initiation of sexual intercourse is considered a badge of honor for boys but is considered deviant for girls. Girls with low self-esteem may be less able to avoid the risk of engaging in early sexual intercourse. Indeed, because our data show that low self-esteem may be triggered by rejection from the peer group and because adolescents may perceive sexual behavior as a way to become popular,27 girls with low self-esteem may be especially vulnerable to engaging in early sexual intercourse to achieve social acceptance.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the association between negative social experiences with peers and teachers during childhood and the early onset of sexual intercourse. Strengths of the study include the longitudinal design, which spanned 8 years and the use of multiple reporting sources including peers and self-reports.

Despite these strengths, the study also had some limitations. First, because of the sensitive nature of the subject, no information was gathered regarding the age of the sexual partners or the degree of intent or coercion during first sexual intercourse.

For the same reason, no information about participants having sexual intercourse was gathered before the participants were aged 13 years (i.e., seventh grade). However, because sexual intercourse before 15 years of age has been shown to put girls especially at risk for health-related problems,2 completed intercourse at age 13 years can be deemed a sufficient indicator of health risk. The fact that the 22% of participants lost through attrition were more often verbally abused by their teacher and less accepted by peers than were participants who remained in the study may have led to an underestimation of the examined associations.

Finally, the results are based on a sample of White, French-speaking participants from similar socioeconomic backgrounds, which limits the generalizability of the findings.

Despite these limitations, our study provides important insights into the potential effects of rejection and verbal abuse by peers and teachers on early sexual intercourse. These negative experiences may be especially problematic for girls’ sexual risk behavior, which underscores the need for health and sexual education programs that specifically target girls and that provide guidance on social relations in general and romance and sexuality in particular. Programs focusing on building self-esteem and reducing delinquent behavior may also be beneficial, especially to girls.

By the same token, our findings emphasize the importance of teacher education and early prevention efforts with disruptive children to prevent later risky sexual behavior and potential negative health outcomes in both genders.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Fonds pour la formation de chercheurs et l’aide à la recherche from the Quebec government.

Human Participant Protection Parental written permission and child verbal assent were obtained each year for all participants. Each year, the instruments were submitted to and approved by the University of Quebec, Abitibi-Temiscamengue, institutional review board and the school board.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors M. Brendgen originated the study, supervised the analyses, and led the writing. B. Wanner completed the analyses. F. Vitaro supervised implementation of the study.

References

- 1.Katchadourian H. Sexuality. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, eds. At the Threshold: The Developing Adolescent. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1990: 330–351.

- 2.Greenberg J, Magder L, Aral S. Age at first coitus: a marker for risky sexual behavior in women. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:331–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Small SA, Luster T. Adolescent sexual activity: an ecological, risk-factor approach. J Marriage Fam. 1994; 56:181–192. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donovan JE, Jessor R. Structure of problem behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:890–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jessor R, Costa F, Jessor L, Donovan JE. Time of first intercourse: a prospective study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;44:608–626. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDougall P, Hymel S, Vaillancourt T, Mercer L. The consequences of childhood peer rejection. In: Leary M, ed. Interpersonal Rejection. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001:213–247.

- 7.Prinstein MJ, Meade CS, Cohen GL. Adolescent oral sex, peer popularity, and perceptions of best friends’ sexual behavior. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28: 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pianta RC. Enhancing Relationships Between Children and Teachers. Washington, DC: American Psychological Assocation; 1999.

- 9.Brendgen M, Wanner B, Vitaro F. Verbal abuse by the teacher and child adjustment from kindergarten through grade 6. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1585–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa FM, Jessor R, Donovan JE, Fortenberry JD. Early initiation of sexual intercourse: the influence of psychosocial unconventionality. J Res Adolesc. 1995;5: 93–121. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spencer JM, Zimet GD, Aalsma MC, Orr DP. Self-esteem as a predictor of initiation of coitus in early adolescents. Pediatrics. 2002;109:581–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavanagh SE. The sexual debut of girls in early adolescence: the intersection of race, pubertal timing, and friendship group characteristics. J Res Adolesc. 2004;14:285–312. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris NM, Udry JR. Validation of a self-administered instrument to assess stage of adolescent development. J Youth Adolesc. 1980;9:271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen J. Statistical Power for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988.

- 15.Coie JD, Dodge KA, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and types of social status: a cross-age perspective. Dev Psychol. 1982;18:557–570. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tremblay RE, Loeber R, Gagnon C, Charlebois P, Larivee S, LeBlanc M. Disruptive boys with stable and unstable high fighting behavior patterns during junior elementary school. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1991;19: 285–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behar L, Stringfield S. A behavior rating scale for the preschool child. Dev Psychol. 1974;10:601–610. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harter S. The Self-Perception Profile for Children: Revision of the Perceived Competence Scale for Children: A Manual. Denver, Colo: University of Denver; 1985.

- 19.Martin A, Ruchkin V, Caminis A, Vermeiren R, Henrich C, Schwab-Stone M. Early to bed: a study of adaptation among sexually active urban adolescent girls younger than age sixteen. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:358–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: reliability, validity, and initial norms. J Youth Adolesc. 1987;17: 117–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanner JM. Growth at Adolescence. Springfield, Il: Thomas; 1962.

- 22.Rose BM, Holmbeck GN, Millstein Coakley R, Franks EA. Mediator and moderator effects in developmental and behavioral pediatric research. Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaccard J, Turrisi R, Wan CK. Interaction Effects in Multiple Regression. London, England: Sage; 1990. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Kaplan HB. Self-attitudes and deviant behavior: new directions for theory and research. Youth Soc. 1982;14:185–211. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casarjian BE. Teacher psychological maltreatment and students’ school-related functioning. Diss Abstr Int Sect A: Human Soc Sci. 2000;60(12-A):4314. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erickson PI, Rapkin AJ. Unwanted sexual experiences among middle and high school youth. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12:319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]