Abstract

Recent studies suggest that months to years of intensive and systematic meditation training can improve attention. However, the lengthy training required has made it difficult to use random assignment of participants to conditions to confirm these findings. This article shows that a group randomly assigned to 5 days of meditation practice with the integrative body–mind training method shows significantly better attention and control of stress than a similarly chosen control group given relaxation training. The training method comes from traditional Chinese medicine and incorporates aspects of other meditation and mindfulness training. Compared with the control group, the experimental group of 40 undergraduate Chinese students given 5 days of 20-min integrative training showed greater improvement in conflict scores on the Attention Network Test, lower anxiety, depression, anger, and fatigue, and higher vigor on the Profile of Mood States scale, a significant decrease in stress-related cortisol, and an increase in immunoreactivity. These results provide a convenient method for studying the influence of meditation training by using experimental and control methods similar to those used to test drugs or other interventions.

Keywords: anterior cingulate gyrus, attention training, control, mental training

In recent years, a number of articles have demonstrated the benefits of various forms of meditation and mindfulness training (1–8). Many of them have tested practitioners of different meditative practices and compared them with controls without any training. Others have compared groups that were equivalent in performance before training but had chosen whether or not to undertake training (2, 4, 9, 10).

In a well done study (2), the experimental group received 3 months of training. The control group consisted of matched persons wanting to learn about meditation. That study used a strong assay of attention, the attentional blink (11); the two groups performed equally before meditation. The experimental group was significantly better after meditation, suggesting that meditation caused an improvement in the executive attention network, most probably in the form of attention used by this task (2).

Nevertheless, problems of subtle differences between control and experimental groups remain in the study discussed above, because the two groups were not completely randomly assigned, and meditators differed greatly in styles of meditation previously practiced (2). Slagter et al. (2) said that “the absence of an association between the amount of prior meditation training and our study results may be due to the fact that there was great variation across the practitioners in the styles and traditions of the previously learned meditation. Longitudinal research examining and comparing the effects of different styles of meditation on brain and mental function and the duration of such effects is needed.”

Styles of meditation differ. Some techniques such as concentration meditation, mantra, mindfulness meditation, etc. rely on mind control or thought work, including focus on an object, paying attention to the present moment, etc. (2, 12–15). Mental training methods also share several key components, such as body relaxation, breathing practice, mental imagery, and mindfulness, etc., which can help and accelerate practitioner access to meditative states (3, 8, 16–19). This background raises the possibility that combining several key components of body and mind techniques with features of meditation and mindfulness traditions, while reducing reliance on control of thoughts, may be easier to teach to novices because they would not have to struggle so hard to control their thoughts. Therefore, integrative body–mind training (IBMT; or simply integrative meditation) was developed in the 1990s, and its effects have been studied in China since 1995. Based on the results from hundreds of adults and children ranging from 4 to 90 years old in China, IBMT practice improves emotional and cognitive performance and social behavior (20, 21).

IBMT achieves the desired state by first giving a brief instructional period on the method (we call it initial mind setting and its goal is to induce a cognitive or emotional set that will influence the training). The method stresses no effort to control thoughts, but instead a state of restful alertness that allows a high degree of awareness of body, breathing, and external instructions from a compact disc. It stresses a balanced state of relaxation while focusing attention. Thought control is achieved gradually through posture and relaxation, body–mind harmony, and balance with the help of the coach rather than by making the trainee attempt an internal struggle to control thoughts in accordance with instruction.

Training in this method is followed by 5 days of group practice, during which a coach answers questions and observes facial and body cues to identify those people who are struggling with the method. The trainees concentrate on achieving a balanced state of mind while being guided by the coach and the compact disc that teaches them to relax, adjust their breathing, and use mental imagery. Because this approach is suitable for novices, we hypothesized that a short period of training and practice might influence the efficiency of the executive attention network related to self-regulation (22).

In the present study, we used a random assignment of 40 Chinese undergraduates to an experimental group and 40 to a control group for 5 days of training 20 min per day. The experimental group was given a short term of IMBT (module one) (20, 21). Training was presented in a standardized way by compact disc and guided by a skillful IBMT coach. Because of their importance the coaches generally have several years of experience with IBMT. The control group was given a form of relaxation training very popular in the West (17, 23).

The two groups were given a battery of tests 1 week before training and immediately after the final training session. A standard computerized attention test measured orienting, alerting, and the ability to resolve conflict (executive attention). The Attention Network Test (ANT) involves responding to an arrow target that is surrounded by flankers that point either in the same or opposite direction. Cues provide information on when a trial will occur and where the target will be (24). The Raven's Standard Progressive Matrix (25, 26), which is a standard culture fair intelligence test; an assay of mood state, the Profile of Mood States (POMS) (27, 28); and a stress challenge of a mental arithmetic task were followed by measures of cortisol and secretory IgA (sIgA) (29–34). All of these are standard assays scored objectively by people blind to the experimental condition. See details in Materials and Methods.

In prior work (24), ANT has been used to measure skill in the resolution of mental conflict induced by competing stimuli. It activates a frontal brain network involving the anterior cingulate gyrus and lateral prefrontal cortex (35, 36). Our underlying theory was that IBMT should improve functioning of this executive attention network, which has been linked to better regulation of cognition and emotion (22, 37). Specifically, we hypothesized that (i) because assignment was random, the training and control group should not differ before training, (ii) the training would improve executive attention (indexed by ANT and POMS scales related to self-regulation and Raven's Standard Progressive Matrices) in the experimental group more than for controls, and (iii) if self-regulation ability improved in the training group, members of the group should also show reduced reaction to stress as measured by cortisol and immunoreactivity assays. In short, the experimental group would show greater improvement in the executive attention network related to self-regulation; the Raven's intelligence test, which is known to differ with improved executive attention; mood scales related to self-control; and cortisol and immunoreactivity measures of stress to a mental arithmetic challenge.

Results

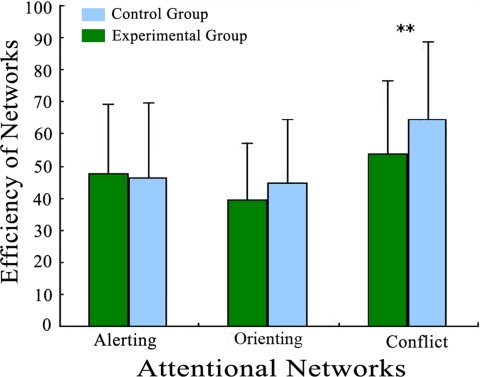

ANOVAs were conducted with group (trained and control) and training session (before and after) as factors, using each of the attention network scores as dependent variables. Before training, no differences were found for alerting, orienting, and executive networks in two groups (P > 0.05). The main effect of the training session was significant only for the executive network [F(1,78) = 9.859; P < 0.01]. More importantly, the group × session interaction was significant for the executive network [F(1,78) = 10.839; P < 0.01], indicating that the before vs. after difference in the conflict resolution score was significant only for the trained group (see Fig. 1). The groups did not differ in orienting or alerting after training (P > 0.05). The result demonstrated that the short-term IBMT practice can influence the efficiency of executive attention.

Fig. 1.

Performance of the ANT after 5 days of IBMT or control. Error bars indicate 1 SD. Vertical axis indicates the difference in mean reaction time between the congruent and incongruent flankers. The higher scores show less efficient resolution of conflict.

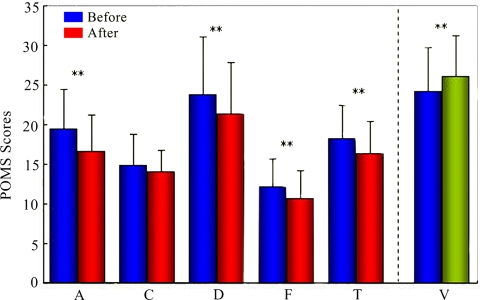

Because the efficiency of executive attention improved, we expected better self-regulation of emotion. We used the POMS to measure emotion in the same two groups. Before training, none of the six scales of POMS showed differences between the two groups (P > 0.05). The ANOVAs revealed a group × session effect for anger–hostility (A) [F(1,78) = 5.558; P < 0.05], depression–dejection (D) [F(1,78) = 5.558; P < 0.05], tension–anxiety (T) [F(1,78) = 11.920; P < 0.01], and vigor–activity (V) [F(1,78) = 7.479; P < 0.01]. After training, the t test indicated there were significant differences in the experimental group (but not the control group) in A, D, T, V, and F (fatigue–inertia); in general, P (positive mood)average < 0.01 (see Fig. 2). The result indicated that short-term IBMT can enhance positive moods and reduce negative ones.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of six scales of the POMS before and after training for the experimental group. Blue bar, five negative moods and one positive mood pretraining; red bar, five negative moods posttraining; green bar, one positive mood posttraining. Significance was found in POMS scales of anger–hostility (A), depression–dejection (D), fatigue–inertia (F), tension–anxiety (T), and vigor–activity (V) posttraining in the experimental group. No significant difference was found in POMS scale C (confusion–bewilderment) posttraining. ∗∗, Paverage < 0.01. Error bars indicate 1 SD.

In previous work, the network associated with executive attention has been related to intelligence (38, 39). We also tested the hypothesis that improvement of efficiency of executive attention accompanies higher intelligence scores. Scores of the Raven's Matrices did not differ before training (P > 0.05). The ANOVAs revealed the main effect of the training session; the Raven's improvement was significant [F(1,46) = 10.171; P < 0.01], but the group × session interaction was not significant, although there was a trend in that direction [F(1,46) = 3.102; P = 0.085]. The t tests showed a significant improvement in the experimental group after training (P < 0.001), but no significant improvement for the control group (P > 0.05). The result revealed that short-term IBMT can improve the Raven's score in the experimental group, although only marginally more so than in the control group.

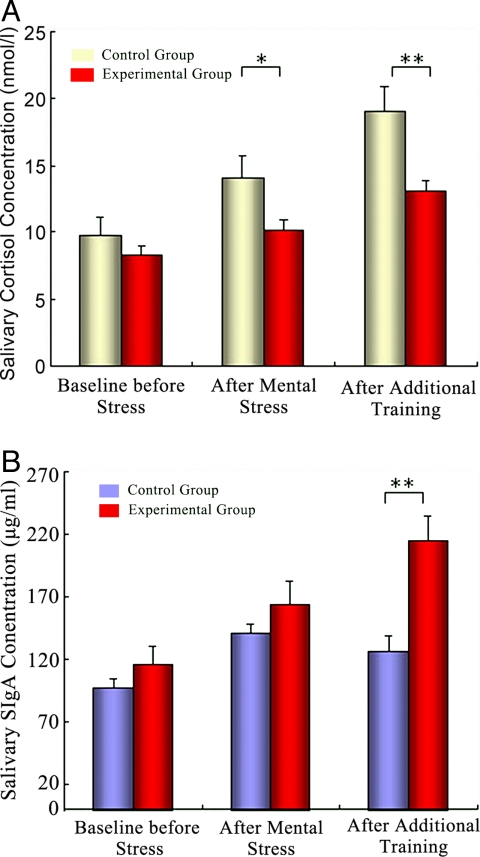

Cortisol and sIgA are indexes of the amount of stress induced by a cognitive challenge (29–34). We applied 3 min of mental arithmetic as an acute stress after 5 days of IBMT or relaxation. Fig. 3 shows that at baseline before stress there was no significant difference between the groups (P > 0.05). This finding indicated no sensitivity for cortisol and sIgA reactions to stress under normal states as found by others (32, 34). After the arithmetic challenge, both groups increased in cortisol activity, indicating that the mental arithmetic challenge was stressful (30). Then the experimental group received an additional 20 min of IBMT and the control 20 min of relaxation training. An ANOVA showed that the group (experimental vs. control) × session (baseline before stress vs. after additional training) interaction was significant [F(1,38) = 6.281; P < 0.01]. The experimental group had a significantly lowered cortisol response to the mental stress after training than did the control group (see Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Physiological changes before and after stress. (A) Comparison of cortisol concentration between the experimental group (red bars) and control group (gray bars) in three different stages after 5 days of training. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01. Error bars indicate 1 SEM. More cortisol secretion indicates higher levels of stress. (B) Comparison of sIgA concentration between experimental group (red bars) and control group (blue bars) at three different stages after 5 days of training. ∗∗, P < 0.01. Error bars indicate 1 SEM. Higher immunoreactivity indicates a better response to stress.

Similarly, there was no significant difference between groups in sIgA at baseline before stress (P > 0.05). However, the mental arithmetic task resulted in a increase of sIgA relative to the baseline as found by others (34). After training, ANOVA showed the group × session interaction was significant [F(1,38) = 10.060; P < 0.001], with the arithmetic challenge resulting in significantly greater sIgA for the experimental group than the control group (see Fig. 3B).

Five days of training reduced the stress response to the mental challenge especially after an additional 20 min of practice.

Discussion

In the ANT and POMS, the experimental group showed significantly greater improvement after 5 days of IBMT than the relaxation control group. Because we randomly assigned subjects to experimental and control groups and used objective tests with researchers blind to the condition, we conclude that IBMT improved attention and self-regulation more than the relaxation control. The reaction to a mental stress was also significantly improved in the experimental group, which showed less cortisol and more immunoreactivity than the control group after the additional training. These outcomes after only 5 days of training open a door for simple and effective investigation of meditation effects. The IBMT provides a convenient method for studying the influence of meditation training by using appropriate experimental and control methods similar to those used to test drugs or other interventions. Our findings further indicate the potential of IBMT for stress management, body–mind health, and improvement in cognitive performance and self-regulation (20, 21).

Although no direct measures of brain changes were used in this study, some previous studies suggest that changes in brain networks can occur. Thomas et al. (40) showed that, in rats, one short experience of acute exposure to psychosocial stress reduced both short- and long-term survival of newborn hippocampal neurons. Similarly, the human brain is sensitive to short experience. Naccache et al. (41) showed that the subliminal presentation of emotional words (<100 ms) modulates the activity of the amygdala at a long latency and triggers long-lasting cerebral processes (41). Brefczynski-Lewis et al. (42) compared novices, who participated in meditation 1 h per day by using three different techniques with expert meditators who had 10,000–54,000 h of practice. Both groups showed activation of a large overlapping network of attention-related brain regions (42). Another situation where a single session changed brain processes is described by Raz et al. (43). Highly hypnotizable persons when given an instruction to view a word as nonsense showed elimination of the Stroop interference effect and also eliminated activity in the anterior cingulate during conflict trials (43). It was also demonstrated that 5 days of attention training with a computer program improved the efficiency of the executive attention networks for children (39). Taken together, we have reason to believe that 5 days of IBMT practice could change brain networks, leading to improvements in attention, cognition, and emotion and reaction to stress.

Why does IBMT work after only a few days of practice whereas studies with other methods often require months? The following are possible reasons.

First, IBMT integrates several key components of body and mind techniques including body relaxation (17), breathing adjustment (18), mental imagery (44, 45), and mindfulness training (12–15), which have shown broad positive effects in attention, emotions, and social behaviors in previous studies (1–8). This combination may amplify the training effect over the use of only one of these components.

Second, because everyone experiences mindfulness sometimes (12, 13, 19, 46, 47), a qualified coach can help each participant increase the amount of this experience and thus guarantee that each practice session achieves a good result (20, 21). For participants with months to years of meditation, there has been the opportunity to make mistakes, correct them, and gradually find the right way. For 5 days of training, quality practice is needed for every session. Recent findings indicate that the amount of time participants spent meditating each day, rather than total number of hours of meditative practice over their lifetime, affects performance on attentional tasks (10).

Third, in one study a selected comfortable music background showed more effects than Mozart's music (21). Having music on the compact disc integrates the practice instruction and occupies the novice's wandering mind via continuous sensory input, maintaining and facilitating the mindful state. Many meditation training methods use audiotapes or compact discs to help beginners (13, 46, 48).

We do not know which of these features is of greatest importance in obtaining change, but we believe that the integration of the various methods into one easy-to-use training package may explain why IBMT is effective at such a low dose. We also regard the work of the trainer as critical. The trainer needs to know how to interact with the trainees to obtain the desired state. Although the trainers are not present during the training sessions, they observe the trainees over television and help them after the session with problems. The trainers could well be a part of the effective ingredient of IBMT, and their role requires additional research.

We have thus far assessed the utility of IBMT with random assignment only for Chinese undergraduates. However, we do not believe that any meditation method is appropriate for every person. In other work, similar, but more preliminary, effects have been observed for Chinese children and adults of many ages. Preliminary data from studies in the United States suggest wider utility of IBMT (20, 21). Some may argue that IBMT effects require a prior belief in the benefits of meditation that would be common in China. However, belief in meditation and traditional medicine is not high among undergraduates in modern China (49). Also a relaxation group used as a control failed to achieve significant improvement. One potentially important difference between Eastern and Western meditation studies is that in China we used group training at the same time of day for each session over 5 days; most of the Western studies used individual meditation at different times. Studies of group dynamics indicate that the group acts to facilitate outcomes (50), and possible differences between individual and group administration of mediation needs further study. Studies of perception, language, mathematics, and psychopathology suggest differences between Americans and Chinese within each of these domains (51–54). Thus culture-specific experiences may subtly shape cognition and direct neural activity in precise ways. If differences between Chinese and American studies of attention training arise, further studies will be needed to determine the reasons.

In previous work, executive attention has been shown to be an important mechanism for self-regulation of cognition and emotion (22, 37, 39). The current results with the ANT indicate that IBMT improves functioning of this executive attention network. Studies designed to improve executive attention in young children showed more adult-like scalp electrical recordings related to an important node of the executive attention network in the anterior cingulate gyrus (22, 37, 39). We expect that imaging studies with adults would show changes in the activation or connectivity of this network after IBMT. Such studies would help to determine the mechanisms by which IBMT improves performance. They may also provide a good objective basis for comparison between training methods.

In summary, IBMT is an easy, effective way for improvement in self-regulation in cognition, emotion, and social behavior. Our study is consistent with the idea that attention, affective processes, and the quality of moment-to-moment awareness are flexible skills that can be trained (55, 56).

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Eighty healthy undergraduates at the Dalian University of Technology [44 males, mean age (± SD) = 21.8 ± 0.55] without any training experiences participated in this study. They were randomly assigned to an experimental or control group (40:40). Forty experimental subjects continuously attended IBMT for 5 days with 20 min of training per day. Forty control subjects were given the same number and length of group sessions but received information from the compact disc about relaxation of each body part. The coach observed them from a closed-circuit television and provided answers to any question after each training session. The human experiment was approved by a local Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from each participant. ANOVA and t tests were applied for analysis.

Measures.

The ANT was administered before and after training (24). Each person received 248 trials during each assessment session. Subtraction of reaction times was used to obtain scores for each attentional network, including alerting, orienting, and conflict resolution (24).

The same two groups of 80 subjects took POMS (27, 28), and 48 subjects [28 males, mean age (± SD) = 21.7 ± 0.53] participated in the Raven's Matrices (25, 26) separately before and after 5 days of training.

Half of the experimental or control group [20:20, 26 males, mean age (± SD) = 21.9 ± 0.97] was chosen randomly to participate in the physiological measures. Mental arithmetic was used as an acute stressor after 5 days of IBMT and relaxation in two groups (29–34). Subjects were instructed to perform serial subtraction of 47 from a four-digit number and respond verbally. During the 3-min mental arithmetic task, participants were prompted to be as fast and accurate as possible. If the participants did not finish the mental arithmetic in time and correctly, the computer would produce a harsh sound to remind the subjects, who were required to restart the task and do it again.

Cortisol and sIgA measures were taken during three periods: baseline before stress, after mental stress, and after additional 20-min training. First, all subjects were given a 5-min rest to get baseline. Second, all subjects were instructed to finish a 3-min mental arithmetic task to test whether there were different stress reactions between two groups. Third, the experimental group practiced an additional 20-min IBMT, whereas the control group relaxed for 20 min to test whether additional training could improve the alterations based on 5 days of training.

To control for variations of cortisol levels over the circadian rhythm, the math stress was performed from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. (32). Saliva samples were collected immediately after each period by one-off injectors and were encased in test tubes in succession, with the tubes placed into a refrigerator under −20°C and then thawed 24 h later for analysis. The concentration of cortisol and sIgA was analyzed by RIA at Dalian Medical University (31–34).

IBMT Method.

IBMT involves several body–mind techniques including: (i) body relaxation, (ii) breath adjustment, (iii) mental imagery, and (iv) mindfulness training, accompanied with selected music background. In this study, IBMT module one was used. A compact disc was developed for module one that included background music. IBMT module one practice included (i) presession, (ii) practice session, and (iii) postsession.

In the presession, usually 1 day before the experiment, the coach gathered subjects to have a free question-and-answer meeting about IBMT practice via coaching techniques to ensure the clear grasp of IBMT for the novices. The coach also set up the exact time, training room, and discipline for the group practice. The most important thing for the coach was to create a harmonious and relaxed atmosphere for effective practice (20, 21).

In the training session, subjects followed the compact disc with body posture adjustment, breathing practice, guided imagery, and mindfulness training accompanied by a music background. Y.-Y.T. gave the practice instructions on the compact disc himself. The practice time was 20 min for 5 days. During the training session, the coach observed facial and body cues to identify those who were struggling with the method and gave proper feedback immediately in postsession.

In the postsession, every subject filled out a questionnaire and evaluated the practice. The coach gave short responses to subjects as required.

IBMT belongs to body–mind science in the ancient Eastern tradition. Chinese tradition and culture is not only a theory of being but also (most importantly) a life experience and practice. The IBMT method comes from traditional Chinese medicine, but also uses the idea of human in harmony with nature in Taoism and Confucianism, etc. The goal of IBMT is to serve as a self-regulation practice for body–mind health and balance and well being and to promote body–mind science research.

IBMT has three levels of training: (i) body–mind health, (ii) body–mind balance, and (iii) body–mind purification for adults and one level of health and wisdom for children. In each level, IBMT has theories and several core techniques packaged in compact discs or audiotapes that are instructed and guided by a qualified coach. A person who achieves the three levels of full training after theoretical and practical tests can apply for instructor status.

IBMT involves learning that requires experience and explicit instruction. To ensure appropriate experience, coaches (qualified instructors) are trained to help novices practice IBMT properly. Instructors received training on how to interact with experimental and control groups to make sure they understand the training program exactly. After each training session, the instructors gave brief and immediate responses to questions raised by the participants, helped those who were observed to be having difficulties, and asked each participant to fill out a questionnaire and make any comments. The most important thing for coaches was to create a harmonious and relaxed atmosphere and give proper feedback for effective practice. The coach believes everyone has full potential and equality and that his/her job is to find and enjoy a person's inner beauty and capacities to help them think better and unfold their potentials rather than to teach them.

A qualified coach is very important for each level of teaching and practice. Without coaching, it is impossible or very difficult to practice IBMT with only compact discs.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Institute of Neuroinformatics staff for assistance with data collection and Kewei Chen and the RIA division at Dalian Medical University for technical assistance. This work was supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 30670699, National 863 Plan Project Grant 2006AA02Z431, Ministry of Education Grant NCET-06-0277, and a Brain, Biology, and Machine Initiative grant from the University of Oregon.

Abbreviations

- IBMT

integrative body–mind training

- ANT

Attention Network Test

- POMS

Profile of Mood States

- sIgA

secretory IgA.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lutz A, Dunne JD, Davidson RJ. In: The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness. Zelazo PD, Moscovitch M, Thompson E, editors. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2007. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slagter HA, Lutz A, Greischar LL, Francis AD, Nieuwenhuis S, Davis JM, Davidson RJ. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh R, Shapiro SL. Am Psychol. 2006;61:227–239. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson RJ, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, Rosenkranz M, Muller D, Santorelli SF, Urbanowski F, Harrington A, Bonus K, Sheridan JF. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:564–570. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000077505.67574.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baer R. Clin Psychol Sci Practice. 2003;10:125–143. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deshmukh VD. Sci World J. 2006;6:2239–2253. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace BA, Shapiro SL. Am Psychol. 2006;61:690–701. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain S, Shapiro SL, Swanick S, Roesch SC, Mills PJ, Bell I, Schwartz GE. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33:11–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan D, Woollacott M. J Alt Complement Med. 2007. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapiro KL, Arnell KA, Raymond JE. Trends Cognit Sci. 1997;1:291–296. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(97)01094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hart W. The Art of Living: Vipassana Meditation: As Taught by SN Goenka. New York: HarperOne; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. New York: Hyperion; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langer EJ. Mindfulness. Reading, MA: Addison–Wesley; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallace BA. The Attention Revolution: Unlocking the Power of the Focused Mind. Somerville, MA: Wisdom; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Vian K, Eckman P, Fang T, Chen L. The Essential Book of Traditional Chinese Medicine. New York: Columbia Univ Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benson H. The Relaxation Response. New York: Avon; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lusk JT. Yoga Meditations. Duluth, MN: Whole Person Associates; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki S. Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind. Boston, MA: Weatherhill; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang Y. Health from Brain, Wisdom from Brain. Dalian, China: Dalian University of Technology Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang Y. Multi-Intelligence and Unfolding the Full Potentials of Brain. Dalian, China: Dalian University of Technology Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Posner MI, Rothbart MK. Educating the Human Brain. Washington, DC: APA Books; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernstein DA, Borkovec TD. Progressive Relaxation Training. Champaign, IL: Research Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan J, McCandliss BD, Sommer T, Raz A, Posner MI. J Cognit Neurosci. 2002;14:340–347. doi: 10.1162/089892902317361886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raven JC. Progressive Matrices: A Perceptual Test of Intelligence. London: HK Lewis; 1938. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raven J, Raven JC, Court JH. Manual for Raven's Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales, Section 1: General Overview. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shacham S. J Personality Assessment. 1983;47:305–306. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4703_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spinella M. J Gen Psychol. 2007;134:101–111. doi: 10.3200/GENP.134.1.101-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, Hellhammer DH. Neuropsychobiology. 1993;28:76–81. doi: 10.1159/000119004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Rao H, Wetmore GS, Furlan PM, Korczykowski M, Dinges DF, Detre JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17804–17809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503082102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polk DE, Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP, Kirschbaum C. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammerfald K, Eberle C, Grau M, Kinsperger A, Zimmermann A, Ehlert U, Gaab J. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deinzer R, Kleineidam C, Stiller-Winkler R, Idel H, Bachg D. Int J Psychophysiol. 2000;37:219–232. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(99)00112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ring C, Drayson M, Walkey DG, Dale S, Carroll D. Biol Psychol. 2002;59:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(01)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan J, McCandliss BD, Fossella J, Flombaum JI, Posner MI. NeuroImage. 2005;26:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Posner MI, Sheese BE, Odludas Y, Tang Y. Neural Netw. 2006;19:1422–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Posner MI, Rothbart MK, Sheese BE, Tang Y. Cognit Affect Behav Neurosci. 2007. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duncan J, Seitz RJ, Kolodny J, Bor D, Herzog H, Ahmed A, Newell FN, Emslie H. Science. 2000;289:457–460. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5478.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rueda MR, Rothbart MK, McCandliss BD, Saccomanno L, Posner MI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14931–14936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506897102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas RM, Hotsenpiller G, Peterson DA. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2734–2743. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3849-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naccache L, Gaillard RL, Adam C, Hasboun D, Clemenceau S, Baulac M, Dehaene S, Cohen L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7713–7717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500542102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brefczynski-Lewis JA, Lutz A, Schaefer HS, Levinson DB, Davidson RJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11483–11488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606552104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raz A, Fan J, Posner MI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9978–9983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503064102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKinney CH, Antoni MH, Kumar M, Tims FC, McCabe PM. Health Psychol. 1997;16:390–400. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe E, Fukuda S, Shirakawa T. BMC Complementary Alt Med. 2005;5:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldstein J. Insight Meditation: The Practice of Freedom. Boston: Shambhala; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lao T, Mitchell S. Tao Te Ching. New York: HarperCollins; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salzberg S, Goldstein J. Insight Meditation: A Step-by Step Course on How to Mediatate. New York: Sounds True; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang G. Med Philos (Humanistic Soc Med Ed) 2006;27:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heathfield SM. How to Build a Teamwork Culture: Do the Hard Stuff. New York: Human Resources About.com; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siok WT, Perfetti CA, Jin Z, Tan LH. Nature. 2004;431:71–76. doi: 10.1038/nature02865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang Y, Zhang W, Chen K, Feng S, Ji Y, Shen J, Reiman EM, Liu Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10775–10780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604416103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nisbett RE, Masuda T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11163–11170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934527100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Draguns JG, Tanaka-Matsumi J. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:755–776. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tononi G, Edelman GM. Science. 1998;282:1846–1851. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Posner MI, DiGirolamo GJ, Fernandez-Duque D. Consciousness Cognit. 1997;6:267–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]