Abstract

Physiological and evolutionary adaptations operate at very different time scales. Nevertheless, there are reasons to believe there should be a strong relationship between the two, as together they modify the phenotype. Physiological adaptations change phenotype by altering certain microscopic parameters; evolutionary adaptation can either alter genetically these same parameters or others to achieve distinct or similar ends. Although qualitative discussions of this relationship abound, there has been very little quantitative analysis. Here, we use the hemoglobin molecule as a model system to quantify the relationship between physiological and evolutionary adaptations. We compare measurements of oxygen saturation curves of 25 mammals with those of human hemoglobin under a wide range of physiological conditions. We fit the data sets to the Monod–Wyman–Changeux model to extract microscopic parameters. Our analysis demonstrates that physiological and evolutionary change act on different parameters. The main parameter that changes in the physiology of hemoglobin is relatively constant in evolution, whereas the main parameter that changes in the evolution of hemoglobin is relatively constant in physiology. This orthogonality suggests continued selection for physiological adaptability and hints at a role for this adaptability in evolutionary change.

Keywords: Baldwin effect, evolvability, adaptability, allosteric, Monod–Wyman–Changeux

The phenotype is shaped both by changes in the genotype and interaction of the organism with the environment. Physiological mechanisms responsive to the environment may enable rapid and reversible variation in phenotype without a change in the genotype. On longer time scales (generations), mutations can alter the genotype and thus permanently alter the phenotype. Despite the mechanistic differences of how physiological variation and evolutionary (genetic) variation arise, both may act in similar ways and on similar molecular targets to change the phenotype. For example, response to the environment can change the activity of an enzyme by a posttranslational modification of an amino acid, such as phosphorylation of serine. Alternatively, mutation can change the activity in a similar way by changing that same amino acid or other amino acids around the active site. This parallel relationship of physiology and genetics to the phenotype has been well appreciated by many evolutionary biologists, first in pregenetic terms in the writings of Baldwin (1), Morgan (2), and Osborn (3), and later in more modern terms by Schmalhausen (4), Waddington (5), Simpson (6), West-Eberhard (7, 8), and Lindquist and coworkers (9, 10). Furthermore, those writers have argued that physiological adaptation can facilitate evolutionary adaptation. By physiological adaptations we mean physiological responses to the environment, also referred to as acclimation. In what is often referred to as the Baldwin effect (11), a stable change in environmental conditions will result in a physiological adaptation that will enable a significant proportion of the population to survive even at reduced fitness. In a subsequent process of genetic assimilation, the physiological adaptation will be “replaced” by an evolutionarily encoded change to the genotype that will confer the adaptation and alleviate the fitness cost. This effect can be implemented in two contrasting ways. In the simplest case, the genetic assimilation can copy the physiological change by replacing an environmental perturbation with an equivalent genetic change. Alternatively, the stabilization can occur by altering some other parameter. Our aim in this study is to enable a quantitative evaluation of the relationship between physiology and evolution by putting this discussion into a very specific biological context that is amenable to quantitative analysis.

Hemoglobin as a Model System

We chose hemoglobin as a model system because it has a highly specific physiological role, as the means of transport of oxygen from the lungs to the tissues. Although hemoglobin is a component of a complex process of respiration, its function can be defined and measured quite independently of the other parts of the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems. The hemoglobin molecule itself should be under strong selection, because only a few other features of the vascular system could possibly be modified to compensate for its function. Furthermore, there are extensive biophysical studies of hemoglobin. It has been investigated as a model of protein structure (12, 13) and as a model for allosteric cooperativity (14, 15). For these reasons, hemoglobin combines a set of almost unique attributes useful for our study: extensively investigated in different organisms and under different conditions, intimately related to an organism's fitness, and representing a relatively independent component of that fitness. The main property of physiological interest is the oxygen saturation curve of hemoglobin, also known as the oxygen equilibrium curve (OEC). This curve reflects the proportion of heme groups that bind oxygen at a given partial pressure of oxygen. Other important phenotypic features such as the solubility of hemoglobin or the ability to bind CO2 are of interest but will be ignored in this study. Therefore, the saturation curve can be thought of as the phenotype under investigation.

Characterization of Hemoglobin Physiology in Terms of p50 and n

The hemoglobin saturation curve (Fig. 1a) is usually characterized empirically in terms of the partial pressure of oxygen at which hemoglobin is half saturated, usually denoted as p50, and the cooperativity of the saturation curve at the half saturation point, denoted as n. It has long been appreciated that the hemoglobin saturation curve is sigmoidial, reflecting cooperativity in the binding of oxygen (16, 17). Extensive measurements show variation of p50 (18, 19) in mammals from 20–40 mm Hg, while n varies in the range 2 to 3.5. Thus, both parameters have been modified during evolution, presumably under strong selective pressure. For example p50 decreases with the weight of animals (18, 19), usually explained by the different basal metabolic needs.

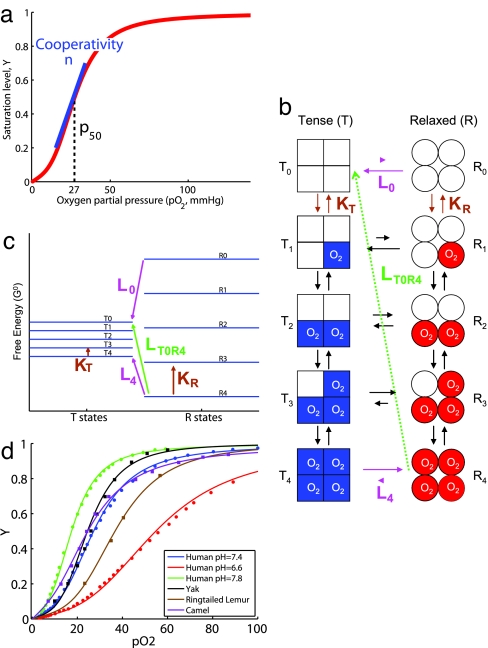

Fig. 1.

Hemoglobin saturation curve and the MWC model. (a) The oxygen saturation curve depicts the proportion of heme groups bound to oxygen as a function of the partial pressure of oxygen. The half-saturation point, p50, is the partial pressure at which half of the sites are occupied. The cooperativity n quantifies the extent to which a change in the partial pressure of oxygen affects the level of saturation. It is schematically shown here although it is actually defined as the slope in the Hill plot [log(Y/(1 − Y)) versus log(pO2)]. (b) The MWC model. The hemoglobin tetramer is assumed to be in one of two symmetric conformations: a state T with low affinity (KT) or a state R with high affinity (KR). In each conformation there are five states subscripted by the number of oxygens bound (0–4). The equilibrium constant between the fully deoxygenated states is L0 (≫ 1) and between the fully oxygenated states is L4 (≪ 1). At low oxygen levels the molecule is in the T state. At high levels of oxygen, the equilibrium shifts toward the R state as binding of oxygen is increased. LT0R4 is the equilibrium constant under standard conditions between states T0 and R4. (c) Energy diagram for the MWC model. The physical meaning of the equilibrium constants L and the affinities K can be understood from this plot depicting the energy levels under standard conditions. For a detailed discussion see SI Text. (d) Measured saturation curves and the MWC fits for several organisms (squares) and several physiological conditions (circles). For depiction in Hill space see SI Fig. 6.

The saturation curve is affected by different physiological conditions. Various effectors, such as diphosphoglycerate [DPG (19), produced as a by-product of metabolism during high oxygen demand] and lowered pH (produced as a by-product of anaerobic metabolism in muscle) affect the saturation curve. When an organism changes from rest to strenuous activity, its rising oxygen needs cause the pH in the tissues to drop, moving the saturation curve to the right (higher p50) [the Bohr effect (20, 21)]. These physiological adaptations (operating on the scale of minutes to hours) can be compared with evolutionary adaptations (operating on the scale of millennia), responding to a change in altitude, lifestyle, physical exertion, body size, or modifications in placental development, affecting the mother–fetus oxygen transport balance.

The Monod–Wyman–Changeux (MWC) Model as a Quantitative Framework for Physiological and Evolutionary Adaptation

p50 and n characterize macroscopically changes in the saturation curve as a result of both physiological and evolutionary adaptation. To determine whether evolution and physiology alter hemoglobin in similar ways, we need to understand how changes in p50 and n reflect microscopic alterations in the hemoglobin molecule itself. Although it is presently impossible to relate the specific mutational or physiological changes to changes in the binding of oxygen to the hemoglobin molecule, an intermediate relationship can be achieved by analyzing the OEC in terms of the well established MWC model (22). The parameters in the model are based on thermodynamic free energies of oxygen binding and conformational transitions in the hemoglobin molecule, in general agreement with the stereochemical mechanism of oxygen binding (14, 15).

The MWC model assumes that the hemoglobin tetramer can be in one of two conformations (Fig. 1b) (22–24). In each conformation, all four subunits are assumed to have the same affinity for oxygen; the binding of oxygen to one subunit is assumed not to affect the binding to another subunit. One of the two quaternary conformations has a high affinity (KR; written as a dissociation constant) and is called the R state, whereas the second state has a low affinity (KT) and is called the T state. The fraction of hemoglobin in state R with k subunits bound to oxygen is denoted Rk and similarly for the T state. The equilibrium constant between the fully deoxygenated T state (T0) and the fully deoxygenated R state (R0) is denoted as L0 (= [T0]/[R0]). An analogous equilibrium constant L4 can be defined for the fully oxygenated states (L4 = [T4]/[R4]; L4 = L0*c4, where c = KR/KT). The model is fully characterized by three parameters (e.g., KR, KT, and L0 or KR, KR/KT, and L4) and all other parameters can be expressed as a combination of these parameters dictated by energy conservation rules (Fig. 1c).

Mammalian hemoglobin saturation curves differ for diverse physiological conditions and in diverse organisms. We analyzed this variation under both evolutionary and physiological conditions, to determine whether the parameters used for physiological adaptations are similar to those fixated after evolutionary adaptations. From the literature we collected a data set of oxygen saturation curves of 25 mammals under similar physiological conditions and a data set of human oxygen saturation curves under different physiological conditions (mainly changes in pH and DPG). We also examined a more limited set for physiological changes in three other mammals. Rather surprisingly, we found that mammalian hemoglobins have explored a domain of parameters orthogonal to the domain explored for physiological adaptations. We discuss the potential significance of this finding for the role of physiological adaptability in evolution, the limitations of the experimental data, and the strength of the conclusions.

Results

Physiological Adaptation and Evolutionary Adaptation Reflected in the OEC.

Using a data set of OECs from 25 different mammals [for examples, see Fig. 1d; data set sources are described in supporting information (SI) Figs. 7 and 8 culled from the hemoglobin literature], we analyzed the values of the half-saturation point, p50, and the cooperativity at half saturation, n. Physiological whole-blood data sets are mostly limited to pH changes in humans (25), although SI Figs. 7 and 8 also include data based on purified hemoglobin for horse, rabbit, and bovine (26) and for changes in DPG and CO2 in humans (27). The physiological effector pH results in a pronounced change in p50 and a relatively small change in n (Fig. 2a; small and large are meant in comparison to the changes in different organisms). p50 changes range from 15 to 60 mmHg (σlogP50 = 0.22), whereas n changes range from 2.75 to 2.95 (σn = 0.07).

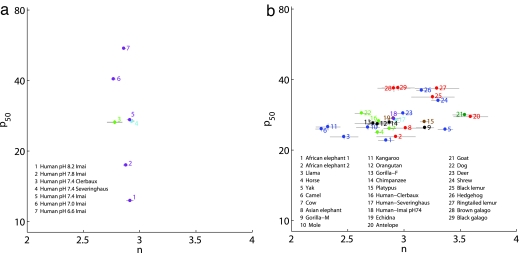

Fig. 2.

Phenotypic parameters for human hemoglobin under varying physiological conditions (a) and for different mammals (b). The parameters are based on fits to data measured by various groups. Different colors denote different sources of information (see details in SI Tables 1 and 2). Note that p50 in units of mmHg is given in log scale.

In contrast, when we analyze the change in these parameters for different organisms under similar physiological conditions, we find that the situation reverses and n changes appreciably whereas p50 changes only to a small extent (Fig. 2b). p50 changes range from 25 to 40 mmHg (σlogP50 = 0.07), whereas n changes range from 2.2 to 3.6 (σn = 0.32). The opposite trend in which parameters vary in physiology versus evolution is shown in Fig. 4c. Several caveats in extracting values of n and p50 are discussed below and in SI Text.

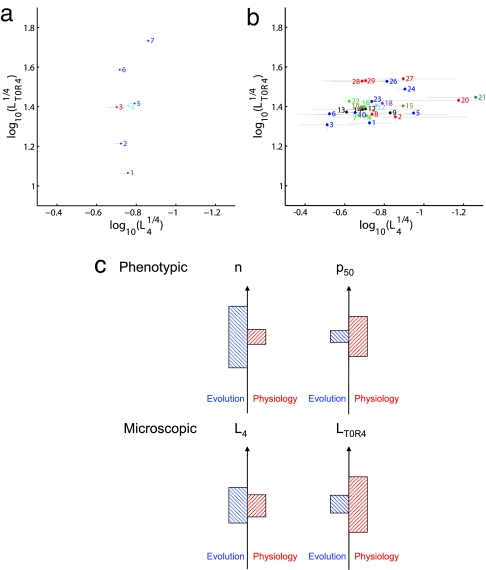

Fig. 4.

Variation in microscopic parameters in evolution and physiology. (a and b) Microscopic parameters for human hemoglobin under varying physiological conditions (a) and for different mammals (b). Parameters are extracted from fits to data measured by various groups (different colors denote different sources of information, see details in SI Tables 1 and 2). (c) The cooperativity n changes more through evolutionary adaptations than through physiological adaptations. In contrast, p50 changes more in physiological adaptations than in evolutionary adaptations. The trend observed for phenotypic parameters is also evident in microscopic parameters. L4 changes more in evolutionary adaptations than by physiological adaptations. In contrast, LT0R4 changes more in physiological adaptations than by evolutionary adaptations. Bar heights are proportional to the SD in the parameters' evolutionary and physiological ranges.

The comparison in terms of n and p50 of physiological change mediated by pH and DPG in humans to evolutionary change across different mammals is striking. It raises the question of whether in other mammals' physiological effectors will act the same way. Data collected by Imai (26) on the impact of various effectors on four organisms (human, horse, rabbit, and bovine; SI Figs. 7 and 8) show that physiological adaptation acts predominantly through p50, with little change in n. Winslow et al. (28) varied the effectors pH, DPG, and pCO2 through their physiological ranges. Unfortunately, the data are available only through the parameters fitted to the Adair model (29), a phenomenological model of hemoglobin that assumes a different affinity for each oxygen binding event. We extracted the phenotypic parameters (p50 and n) from the fitted parameters (see Methods) (SI Figs. 9 and 10). Again, a change in pH affects mostly p50, whereas a change in DPG or CO2 also affects n to some extent. In general, although the contrast in this case is less striking, the difference with respect to the evolutionary scenario is still quite clear. Yet we do not know how to relate p50 and n to structural or thermodynamic features of the hemoglobin molecule. We therefore proceeded to analyze the process of adaptation from the viewpoint of a microscopic model using the MWC model.

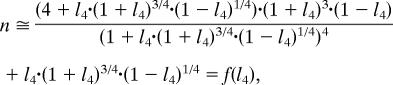

The MWC model is traditionally analyzed in terms of the parameters L0, KR, and KT. This set of parameters has the advantage of having concrete, easy-to-visualize “mechanical” interpretation in terms of the protein, and they are very familiar to those who have studied hemoglobin. Yet these parameters have two disadvantages: they show very unequal sensitivity (Fig. 3a) to experimental variation in measurements and most importantly they do not map independently to the two principal physiological parameters, p50 and n. The model can be reparameterized by other combinations of these parameters, as discussed in SI Text. If instead of L0 and KR, we use the combination L0*KR4 (LT0R4) and L4, the data will be very constrained by L4 and LT0R4, while the other parameter, KR can have a wide range of values. A further advantage of the parameter set L4, LT0R4, KR, is that these parameters can independently be related to p50 and n. As shown in SI Text, we find that LT0R4 can be robustly estimated and is strongly correlated (Fig. 3c) with the phenotypic parameter p50. In fact, our analysis (see SI Text) demonstrates that to first order

Microscopically, LT0R4 is the equilibrium constant between the T0 (fully deoxygenated tense conformation) and R4 (fully oxygenated relaxed conformation) states under standard conditions (Fig. 1c).¶ For a more elaborate discussion of these issues see SI Text.

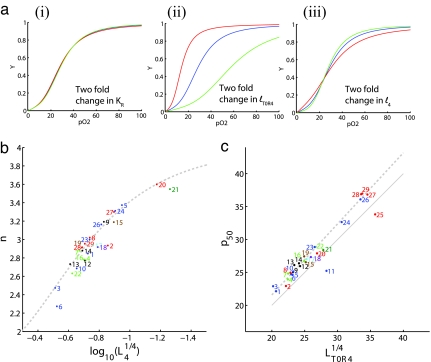

Fig. 3.

Relationship of microscopic parameters to phenotypic saturation properties. (a) Sensitivity of the saturation curve to different parameter changes. Normal human saturation curve (blue) versus 2-fold increase (red) or decrease (green) in the value of KR while keeping L4 and KT constant (i); KT (equivalently lT0R4) while keeping L4 and KR constant (ii); and l4 while keeping KR and LT0R4 constant (iii). We use the notation lT0R4 = LT0R41/4 and l4 = L41/4 as explained in SI Text. (b) The cooperativity n depends strongly on L4. Parameters based on nonlinear least-squares curve fitting are shown for different organisms. The gray dotted line shows the theoretical relationship given in the text and is derived in SI Text. (c) The half-saturation pressure, p50, depends strongly on LT0R4. Values of the parameters for different organisms are shown. The thick dotted line shows the first-order theoretical relationship given in the text; the thin dotted line shows the second-order approximation. For full derivations, see SI Text. Mammals' index legends are as in Fig. 2b pO2 and pO5 are in units of mmHg.

L4 correlates with the cooperativity, n (Fig. 3b). The connection between n and L4 as well as p50 and LT0R4 is a basic property of the MWC model in the parameters domain occupied by hemoglobin. This can be understood from an analysis of the energy-level diagram and an analytic derivation (see SI Text and SI Figs. 11 and 12) where we demonstrate that

|

where for simplicity of notation we use l4 = L41/4. Although the MWC parameter KT can be robustly extracted from the data, KT itself does not independently dictate a phenotypic parameter.

Microscopic Parameters Show Orthogonal Patterns of Change in Physiological and Evolutionary Adaptations.

We extracted the model parameters for each of the saturation curves under varying physiological conditions. The affinity KT and thus the value of LT0R4 changes markedly under physiological variation (Fig. 4a): LT0R4 varies between 104 and 107 (σlogLTOR4 = 0.88). For the same conditions, the value of L4 remains relatively constant, in the range from 10−2.8 to 10−3.2 (σlogL4 = 0.2). It has been previously reported that KT changes by physiological effectors (30), which can be understood by noting that most effectors bind preferentially to the T state, causing some change in KT.

Given the previous physiological observations on parameter changes, how do these compare with changes under evolutionary adaptations? We find that the value of L4 varies appreciably in evolution, whereas the value of LT0R4 shows small variation (Fig. 4b). L4 varies in the range 10−2 to 10−5 (σlogL4 = 0.67), whereas LT0R4 varies in the range 10−5.2 to 10−6.2 (σlogLT0R4 = 0.27). The evolutionary changes are thus markedly different from the physiological changes (Fig. 4c).

Discussion

With the goal of understanding the relationship of physiological variation and evolutionary variation, we have examined the behavior of hemoglobin in diverse mammals. In doing so we have relied on existing data sets of oxygen saturation, some collected 40 years ago. We have extracted parameters of the MWC model by curve-fitting to the published raw data and estimated the reliability of these parameters. We have reparameterized the MWC model, effectively reducing the three parameters to two parameters whose variation has a strong effect on the measurable data. We have found that a specific pair of these parameters correlate with two common phenotypic parameters for hemoglobin, the half-saturation (p50) and the steepness of the curve at that value (the Hill coefficient, n). When using the reparametrized microscopic parameters to the physiological variation in human hemoglobin (or to more limited data of horse, rabbit, and cow), we have found that one of these parameters, LT0R4, is much more affected than the other, L4. In examining the hemoglobin of 25 mammals under similar conditions, we found that the relative variation in these two parameters was reversed, with stronger evolutionary change in L4 than in LT0R4. The contrasting mode of variation suggests that physiological changes in hemoglobin are connected to evolutionary changes in some nonrandom way that begs an explanation.

It is important to recognize some of the limitations of this type of analysis. Different measurement techniques and experimental protocols were followed in collecting the data from different organisms. Some of the data sets involved as few as four experimental data points and were not originally collected with the intention of extracting the cooperativity. The published data rarely have any analysis of errors, the most important of which may be systematic, rather than random. Also, when multiple specimens of a given species were measured, the reported data were often the average of the experimental values. In some cases, the animals, unlike human, are known to have multiple hemoglobin variants expressed at comparable levels, detectable by native isoelectric focusing. It is not known whether these variants differ appreciably in their saturation curves, which could have the effect of decreasing the apparent n. There are always concerns about the lability of DPG in the samples and the production of methemoglobin on storage of whole blood. If the DPG levels become substoichiometric, there will be a loss in cooperativity (31). How well this was appreciated and controlled in each case is hard to judge. Some of these physiological and methodological variations will only change the physiological working point and not affect the conclusions; in other cases, it may be expected to flatten the dissociation curves. Even with these caveats in the available data, we feel that there is strong justification in trying to connect physiology and evolution in a single biochemical model.

Proposed Explanations for the Different Parameters Used for Adaptations: A Possible Orthogonality Principle or Selection for Adaptability.

The observation that the microscopic route taken by physiological adaptations is not fixed by evolutionary adaptation but rather that a different “knob” is used for evolutionary adaptations can have several explanations. One explanation is that the LT0R4 knob used by physiological adaptation is not fixed to a new value because the alternative adaptation that changes the value of n (L4) has the advantage of not compromising the future ability to physiologically modulate p50, thus conserving the dynamic range for physiologic adaptability (Fig. 5). Another possible factor is that L4 is more amenable to genetic changes than LT0R4 and therefore has a higher chance of changing by random mutations. Once a mutation is found that gives the correct effect on the phenotype it will be fixed. The analysis of this possibility would benefit from a detailed mapping between the genotypic sequence space and the space of model parameters, something that might be possible by examining recombinant mutant hemoglobins. A third explanation is that there is some optimality to the values of n and p50 adapted through evolution. It should be pointed out that the saturation at some other value of the partial pressure of oxygen, e.g., p20, might be optimized for oxygen unloading, and this value would be tunable both by changes in n and p50, or specifically, changes in LT0R4 and L4. The exact optimization would be hard to predict and will presumably include other fitness advantages, such as the transport of oxygen to the fetus (32–34). We still lack a full understanding of the importance for the phenotype of the evolutionary changes in the cooperativity observed in different mammals.

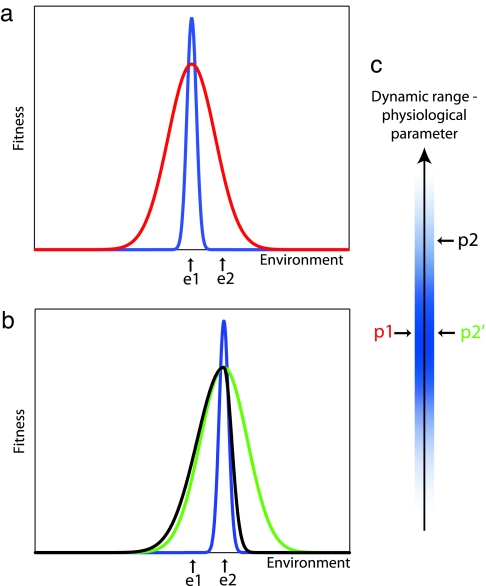

Fig. 5.

Schematic of the Baldwin effect and its possible implementations. (a) The fitness of an organism, when adapted to environment e1, is plotted as a function of the prevailing environmental conditions. Physiological adaptation (red), also referred to as somatic adaptation, increases the inherent (blue) range of fitness of the organism. On a change from condition e1 to e2, instead of extinguishing all organisms (assuming mutations do not yet exist), physiological adaptation allows survival. (b) After evolutionary adaptation to environment e2 the maximal fitness is centered at the prevailing condition. If evolutionary adaptation occurred by genetic assimilation of the microscopic physiological response (black), the range of further physiological adaptations would be compromised. In contrast, if the evolutionary adaptation was achieved via an independent parameter, survival by physiological adaptation would still be possible under further changing conditions (green). (c) The physiological adaptation is assumed to have a limited biochemical dynamic range. Evolutionary adaptation by changing the original value of p1 to p2 (black line) compromises the ability to further increase this parameter in the future to the same extent as before. An adaptation using an orthogonal axis (p2′; green line) preserves the full dynamic range for physiological adaptations.

If the Baldwin Effect Occurs in Hemoglobin, It Is Not Manifested Using Identical Physiological and Evolutionary Parameters.

The simplest implementation of the Baldwin effect is that physiological adaptations will be replaced by evolutionary adaptations (a genocopy) by means of identical microscopic changes. In this view, if LT0R4 changes physiologically much more than L4, then this change should also be replicated in evolution. Our analysis indicates that this is not the case for mammalian hemoglobins, where L4 changes more in evolution than LT0R4. Thus, this simple mode of implementation is not fulfilled. Yet as described above, the separation of change in LT0R4 at the physiological time frame from L4 in the evolutionary time frame suggests that there might be some way in which these two adaptations interact, if not by the assimilation of one by the other.

We suggest that this orthogonality of evolutionary and physiological microscopic parameters for hemoglobin may be selected for a very important reason, so that the adaptive ranges can be maintained in new environments (compare green and black curves in Fig. 5b). This principle may be widely used. It will be instructive to examine hemoglobin in experiments assaying the changes elicited by physiological effectors in many more diverse organisms. To explore the generality of our findings to other biological systems will certainly require accurate experimental measurements in a very large number of animals. It seems possible that the ever-accelerating rate of data collection will soon enable exploration of this relationship in systems that show both physiological and developmental adaptations, as well as evolutionary change, such as systems that regulate protein and RNA expression, enzyme activity, and metabolism.

Methods

Data Collection.

OECs were collected by a literature survey (SI Tables 1–4) and extracted by using GraphClick (Arizona Software, San Francisco, CA). In most cases, the measurements were performed at 37°C using either whole blood or hemolysates (for different organisms) or purified hemoglobin reconstituted with physiological effectors (for different physiological conditions). A more detailed description is given in SI Text.

Numerical Curve Fitting and Parameter Extraction.

We used the fminsearch algorithm in Matlab (Mathworks, Framingham, MA) to perform the curve fitting. The parameters were extracted by a nonlinear least-squares algorithm using the simplex method, minimizing the squared differences in Hill space [i.e., log(Y/(1 − Y)]. We optimized in log parameter space with initial conditions of KR = 100, L4 = 10−3, and KT = 102. The effect of using other optimization techniques, initial conditions, etc., are discussed in SI Text. The values of n and p50 were extracted from the fitted MWC model by interpolating the resulting saturation curve to find the value of p50 and calculating the slope at half-saturation in Hill space. We calculate the cooperativity at half-saturation n50 rather than the maximum cooperativity nmax as the former is more widely reported.

Sensitivity Analysis.

To estimate the error bars, we extracted a model of the noise by analyzing the residuals of our fits. We aggregated all of the data sets and then computed the distribution of the residuals. We find that in Hill space [i.e., log(Y/(1 − Y))] the errors do not depend on the value of Y, in agreement with previous reports by Imai (21). The errors have a SD of ≈0.05 in Hill space. Using this noise model, we created an ensemble of synthetic data sets by adding simulated random measurement errors to each data set. We fit each of the synthetic data sets, and thus extracted a distribution for the values of the parameters. The SD of this distribution was taken as an estimate of our error bars. This error analysis have limitations: the residuals of adjacent points tend to be correlated in sign rather than randomly distributed, indicating systematic errors in the measurements or limitations of the MWC framework. Moreover, the accuracy of different data sets can vary significantly, thus requiring separate error models that could not be constructed with the limited data available. A more detailed discussion is provided in SI Text.

Quantifying and Contrasting Parameter Ranges.

To contrast physiological and evolutionary variation, we quantify the differences in the parameter ranges by using the SD of the logged values of the parameters denoted by σX. Further details and motivation for this choice are supplied in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Walter Fontana, Frank Bunn, David Osterbur, Stuart Edelstein, Robert Winslow, John Gerhart, Bill Eaton, Stephen Stearns, Kiyohiro Imai, Takashi Yonetani, Maurizio Brunori, Tom Shimizu, Pedro Bordalo, Van Savage, and Eric Deeds for many helpful discussions. M.W.K. was supported by National Institute of Child Health Grant 5R01-HD037277-09. M.P.B. was supported by the National Science Foundation Division of Mathematical Sciences.

Abbreviations

- MWC

Monod–Wyman–Changeux

- OEC

oxygen equilibrium curve

- DPG

diphosphoglycerate.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0707673104/DC1.

It was previously appreciated that L4*KT4 is an approximation to a parameter called Pm and referred to as the median oxygen pressure (21).

References

- 1.Baldwin JAM. Am Nat. 1896;30:441–451. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgan CL. Habit and Instinct. London: Arnold; 1896. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osborn HF. A Mode of Evolution Requiring Neither Natural Selection Nor the Inheritance of Acquired Characters Organic Selection. New York: New York Acad Sci; 1896. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmalhausen II. Factors in Evolution: The Theory of Stabilizing Selection. Chicago: Univ Chicago Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waddington CH. Evolution. 1953;7:118–126. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson GG. Evolution. 1953;7:110–117. [Google Scholar]

- 7.West-Eberhard MJ. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1989;20:249–278. [Google Scholar]

- 8.West-Eberhard MJ. Developmental Plasticity and Evolution. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Queitsch C, Sangster TA, Lindquist S. Nature. 2002;417:618–624. doi: 10.1038/nature749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutherford SL, Lindquist S. Nature. 1998;396:336–342. doi: 10.1038/24550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirschner MW, Gerhart JC. The Plausibility of Life. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perutz MF, Rossmann MG, Cullis AF, Muirhead H, Will G, North ACT. Nature. 1960;185:416–422. doi: 10.1038/185416a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickerson RE, Geis I. Hemoglobin. San Francisco, CA: Benjamin/Cummings; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perutz MF. Nature. 1970;228:726–739. doi: 10.1038/228726a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perutz MF, Wilkinson AJ, Paoli M, Dodson GG. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1998;27:1–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill AV. J Physiol (London) 1910;40:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voet D, Voet JG. Biochemistry. New York: Wiley; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt-Neilsen K, Larimer JL. Am J Physiol. 1958;195:424–428. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1958.195.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott AF, Bunn HF, Brush AH. J Exp Zool. 1977;201:269–288. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402010211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bunn F, Forget BG. Hemoglobin: Molecular, Genetic, and Clinical Aspects. Sunderland, MA: Saunders; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imai K. Allosteric Effects in Hemoglobin. London: Cambridge Univ Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux JP. J Mol Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eaton WA, Henry ER, Hofrichter J, Bettati S, Viappiani C, Mozzarelli A. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:586–599. doi: 10.1080/15216540701272380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eaton WA, Henry ER, Hofrichter J, Mozzarelli A. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:351–358. doi: 10.1038/7586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mawjood AH, Imai K. Jpn J Physiol. 1999;49:379–387. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.49.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imai K. In: Brussels Hemoglobin Symposium. Schnek G, Paul C, editors. Brussels, Belgium: Faculte des Sciences, Editions de l'Universite de Bruxelles; 1983. pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benesch R, Benesch RE. Nature. 1969;221:618–622. doi: 10.1038/221618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winslow RM, Samaja M, Winslow NJ, Rossi-Bernardi L, Shrager RI. J Appl Physiol. 1983;54:524–529. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.54.2.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adair GS. J Biol Chem. 1925;63:529–545. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imai K. J Mol Biol. 1983;167:741–749. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kister J, Poyart C, Edelstein SJ. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:12085–12091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Kobayashi K, Kitazawa K, Imai K, Kobayashi M. Zool Sci. 2006;23:49–55. doi: 10.2108/zsj.23.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Kobayashi K, Sasagawa K, Imai K, Kobayashi M. Zool Sci. 2003;20:1087–1093. doi: 10.2108/zsj.20.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Miki M, Sasagawa K, Kobayashi M, Imai K, Kobayashi M. Zool Sci. 2003;20:23–28. doi: 10.2108/zsj.20.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.