Abstract

The differentiation of skeletal myoblasts is characterized by permanent withdrawal from the cell cycle and fusion into multinucleated myotubes. Muscle cell survival is critically dependent on the ability of cells to respond to oxidative stress. Base excision repair (BER) is the main repair mechanism of oxidative DNA damage. In this study, we compared the levels of endogenous oxidative DNA damage and BER capacity of mouse proliferating myoblasts and their differentiated counterpart, the myotubes. Changes in the expression of oxidative stress marker genes during differentiation, together with an increase in 8-hydroxyguanine DNA levels in terminally differentiated cells, suggested that reactive oxygen species are produced during this process. The repair of 2-deoxyribonolactone, which is exclusively processed by long-patch BER, was impaired in cell extracts from myotubes. The repair of a natural abasic site (a preferred substrate for short-patch BER) also was delayed. The defect in BER of terminally differentiated muscle cells was ascribed to the nearly complete lack of DNA ligase I and to the strong down-regulation of XRCC1 with subsequent destabilization of DNA ligase IIIα. The attenuation of BER in myotubes was associated with significant accumulation of DNA damage as detected by increased DNA single-strand breaks and phosphorylated H2AX nuclear foci upon exposure to hydrogen peroxide. We propose that in skeletal muscle exacerbated by free radical injury, the accumulation of DNA repair intermediates, due to attenuated BER, might contribute to myofiber degeneration as seen in sarcopenia and many muscle disorders.

Keywords: oxidative stress, XRCC1, DNA ligases, DNA single-strand breaks, 8-oxoguanine

Various properties of skeletal muscle, including a high rate of oxygen metabolism, render it particularly susceptible to free radical injury (1). Indeed, many muscle disorders have been attributed to toxic actions of reactive oxygen species (ROS). DNA base lesions arising from oxidation are processed primarily by the base excision repair (BER) pathway. The damaged bases are excised by DNA N-glycosylases, which generate apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) sites. AP sites produced by the spontaneous loss of damaged bases also are processed by BER. Free radicals produce various types of abasic lesions. Two subpathways, short- and long-patch BER, restore the template by replacement of one or more nucleotides at the lesion site, respectively (2). Therefore, the BER pathways should play a key role in the control of muscle cell integrity. In general, DNA repair is attenuated by differentiation in most types of differentiated cells. Owing to their nonproliferative nature, terminally differentiated cells are unable to use replication-associated pathways, such as homologous recombinational repair, making them particularly sensitive to loss or decreased efficiency of prereplicative repair pathways, such as nucleotide excision repair (NER), BER, and single-strand break repair (SSBR). The down-regulation of global genomic NER has been reported in several differentiated cell systems. However, within active genes, both DNA strands continue to be efficiently repaired by a mechanism called differentiation-associated repair (3) and recently renamed transcription domain-associated repair (4). The information on BER activity along the cell differentiation program is limited. Further, the accumulation of abortive DNA repair intermediates, because of impaired SSBR, is responsible for neurological disorders (5, 6).

In skeletal muscle, tissue maintenance and repair are ensured by satellite cells that reside under the basal lamina (1). These cells can be readily isolated, cultured, and induced to differentiate into mononucleated myocytes that precede the fusion in multinucleated myotubes (7, 8).

Here we use mouse satellite cells differentiated in vitro as a model to study BER regulation during skeletal muscle differentiation. This cell system recapitulates the process in vivo as shown by irreversible cell cycle withdrawal, repression of cell proliferation-associated genes, and expression of muscle-specific genes during terminal differentiation in vitro as determined by genome-wide analysis (9). We show that long-patch BER, which shares several partners with DNA replication, is impaired in myotubes, and, to a minor extent, short-patch BER also is decreased. In either case, terminally differentiated cells accumulate unligated repair intermediates in vitro. This finding is in agreement with the lack of DNA ligase I in myotubes and the down-regulation of XRCC1 during differentiation with subsequent destabilization of DNA ligase IIIα. The attenuation in myotubes of BER, and likely of XRCC1-dependent SSBR, is associated with the accumulation of DNA single-strand breaks (SSB) and γH2AX foci upon cell exposure to hydrogen peroxide. This mechanism might account for the exquisite sensitivity of myotubes to oxidative injury.

Results

Regulation and Effects of Changes in Redox Homeostasis During Muscle Differentiation.

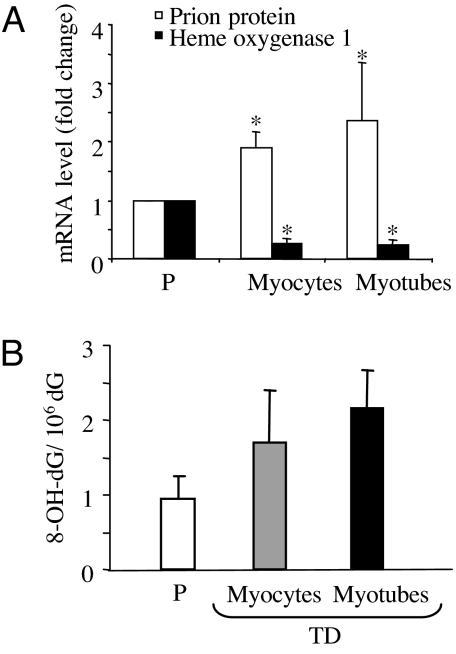

The expression of marker genes of oxidative stress response was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR during in vitro muscle differentiation. Among the genes tested, down-regulation of heme oxygenase 1, a redox-regulated enzyme (10), and up-regulation of the prion protein that is a quencher of hydroxyl radicals (11) were detected in both myocytes and myotubes when compared with myoblasts (Fig. 1A). The changes in expression levels of genes involved in oxidative stress response suggest that ROS are produced during myoblast differentiation.

Fig. 1.

Regulation of oxidative stress response and DNA oxidation levels of muscle cells as a function of the differentiation state. (A) Expression of oxidative stress response genes in proliferating versus terminally differentiated cells (myocytes and myotubes). mRNA levels were determined by RT-PCR, and values were normalized (myoblast value is set at 1). Error bars indicate standard deviation (*, P < 0.001). (B) DNA levels of 8-OH-dG in proliferating versus myocytes and myotubes. Genomic DNA was isolated and analyzed for 8-OH-dG content by HPLC-ED. The data represent the mean of three independent experiments, and the standard deviation of the means are reported. Proliferating (P) and terminally differentiated (TD) cells.

Next, we examined the steady-state level of 8-OH-dG by HPLC-ED in proliferating myoblasts and terminally differentiated myocytes and myotubes. Fig. 1B shows that there was a trend toward higher 8-OH-dG levels in terminally differentiated cells, compared with proliferating cells, although the difference was not statistically significant.

The changes in oxidative stress gene expression and the increased level of DNA oxidation in terminally differentiated muscle cells likely reflect an extra burden for DNA repair associated with free radical generation during the differentiation process.

Base Excision Repair Is Less Efficient in Myotubes than in Myoblasts.

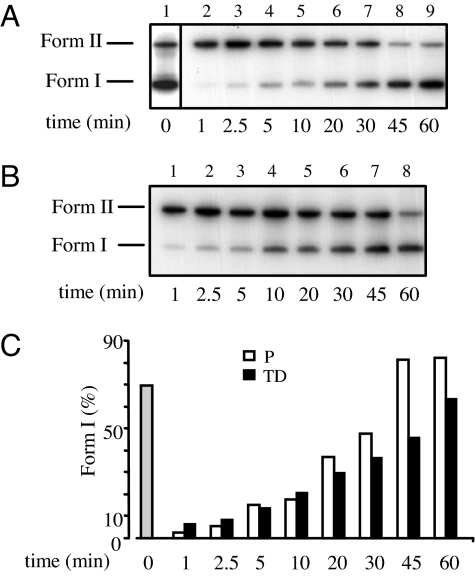

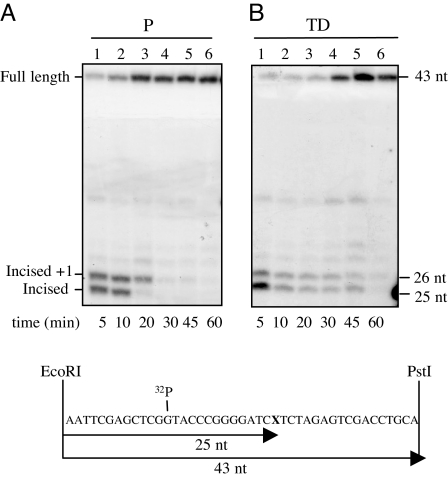

BER reactions were conducted in vitro by using as substrate a 32P-labeled circular plasmid containing a single AP site (pGEM-AP). Whole-cell extracts were prepared from proliferating myoblasts and terminally differentiated myotubes and incubated in the presence of dNTPs for increasing periods of time. After 10 min postincubation, a delay in the repair rate of AP sites by myotube extracts was observed, compared with extracts from proliferating cells (Fig. 2). Nicked forms (Form II), which consist of both incised and unligated polymerization products, persisted for longer times in the case of terminally differentiated cells (Fig. 2B) than in myoblasts (Fig. 2A), although completion of repair (reconstitution of fully repaired Form I plasmids) was eventually observed in both cases at 1-h repair time (Fig. 2C). To better characterize the steps responsible for the delayed repair kinetics, the 32P-labeled repaired plasmid molecules were digested with EcoRI and PstI to produce a 43-nt fragment that originally contained the lesion (Fig. 3). In this assay, repair intermediates are identified as 25-nt fragments that correspond to the incision step or >25 nt depending on the patch size of the polymerization step. The slower rate of repair of myotubes, compared with myoblasts, was confirmed. In addition, a clear accumulation of repair intermediates was detected in these cell extracts. In particular, the intensity of the band corresponding to complete repair was lower as a function of time in terminally differentiated (Fig. 3B), compared with proliferating (Fig. 3A), cell extracts. This finding was associated with the persistence for longer times of the 25-nt incised and 26-nt gap-filling products. The repair of AP sites in myotubes is affected by inefficient processing of repair intermediates.

Fig. 2.

BER efficiency of cell extracts from proliferating and terminally differentiated muscle cells. In vitro repair reactions were performed by using whole-cell extracts and as substrate a 32P-labeled circular plasmid containing a single AP site (pGEM-AP). Repair capacity was monitored by measuring the relative yield of nicked (Form II) and supercoiled (Form I) plasmid molecules by agarose gel electrophoresis. (A and B) Repair kinetics of the AP site by extracts of proliferating (A) and terminally differentiated (B) cells. (A) Lane 1, untreated pGEM-AP plasmid; lanes 2–9, pGEM-AP plasmid after incubation with extracts of myoblasts for increasing periods of time (1, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 30, 45, and 60 min). (B) Lanes 1–8, pGEM-AP plasmid after incubation with extracts of myotubes as indicated earlier. (C) The radioactivity in the bands corresponding to Forms I and II was quantified by electronic autoradiography (Instant Imager). Repair efficiency is expressed as relative amount of Form I over total radioactivity in each lane. Gray bar, untreated plasmid; white bar, proliferating (P) cell extracts; black bar, terminally differentiated (TD) cell extracts. At least three independent extracts per cell type were tested.

Fig. 3.

Kinetics of formation and persistence of BER intermediates in cell extracts from proliferating and terminally differentiated muscle cells. In vitro repair reactions were performed by using whole-cell extracts and as substrate a 32P-labeled circular plasmid containing a single AP site (pGEM-AP). Repaired plasmid molecules were digested with EcoRI and PstI and analyzed by a 15% urea-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The 43-nt fragment (full length) represents molecules that either contain the lesion or are fully repaired. The 25-nt fragment indicates the occurrence of the incision step; fragments of >25 nt indicate the resynthesis step. Repair kinetics of the AP site by extracts of proliferating (A) or terminally differentiated (B) cells. Lanes 1–6, pGEM-AP plasmid after incubation with cell extracts for increasing periods of time (5, 10, 20, 30, 45, and 60 min). The position in the gel of DNA size markers is indicated. Experiments were repeated three times, and one representative experiment is shown. Proliferating (P) and terminally differentiated (TD) cells.

Short- and Long-Patch Base Excision Repair Are both Impaired in Myotubes.

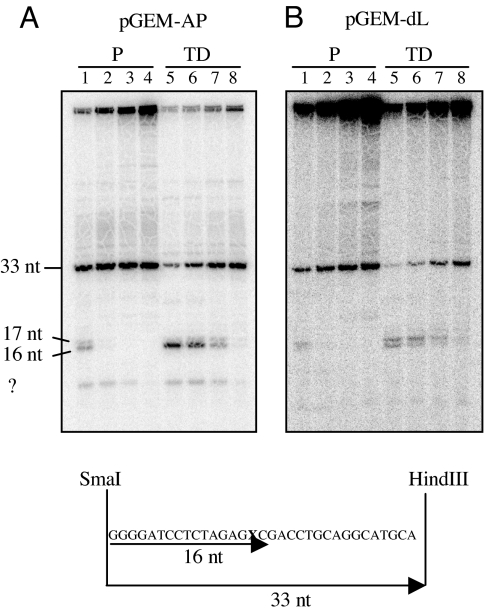

BER is subdivided into two subpathways: short- and long-patch BER. To place the observed delay in repair in terminally differentiated muscle cells in the context of the BER subpathways, we next performed an in vitro repair assay on plasmid DNA containing either a regular abasic site (pGEM-AP) or a 2-deoxyribonolactone (dL) residue (pGEM-dL) [Fig. 4 and supporting information (SI) Fig. 7]. dL is an oxidative lesion that is processed exclusively by the long-patch BER pathway (12), which results in the repair synthesis of two or more nucleotides. Modified plasmids were incubated in the presence of proliferating or terminally differentiated muscle cell extracts in a buffer containing α-32P-TTP. Repaired DNA was digested with SmaI and HindIII restriction endonuclease to free a fragment that originally contained the lesion. As shown in Fig. 4A, the repair of the AP site by terminally differentiated cell extracts was less efficient than by proliferating cell extracts, and 1-nt gap-filling products accumulated at early repair times. These repair intermediates are compatible with the processing of AP sites in myotubes mainly by short-patch BER, but their persistence indicates that the end-processing machinery is not fully functional. The repair of the dL residue (Fig. 4B) was even more affected in terminally differentiated cell extracts than that of the AP site. In this case, the accumulation of 2-nt gap-filling products confirmed the occurrence of long-patch BER at dL residues (12), suggesting that the processing of the long-patch repair intermediates also were impaired in terminally differentiated cells. The quantitative analysis of the repair products detected in three independent experiments is provided in SI Materials and Methods and SI Fig. 7.

Fig. 4.

Short- and long-patch BER efficiency of cell extracts from proliferating and terminally differentiated muscle cells. Repair assay on plasmid DNA containing a regular abasic site (pGEM-AP) or a 2-deoxyribonolactone residue (pGEM-dL). pGEM (AP/dL) was incubated with cell extracts in the presence of α-32P-TTP. After digestion of DNA with SmaI and HindIII restriction endonuclease, repair products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 15% urea-denaturing polyacrylamide gels. Repair kinetics of the AP site (A) or the dL residue (B). Lanes 1–4, extracts of myoblasts; lanes 5–8, extracts of myotubes for increasing period of times (15, 30, 60, and 120 min). Experiments were repeated three times, and one representative experiment is shown. The quantitative analysis of the repair products detected in three independent experiments is provided as supporting information (SI Fig. 7). Proliferating (P) and terminally differentiated (TD) cells.

On the basis of all these findings, we can conclude that the efficiency of both short- and long-patch BER decreases when muscle cells differentiate, and that the affected steps are likely to involve BER enzymes that process the repair intermediates.

The Ligation Step Is Defective in Terminally Differentiated Muscle Cells.

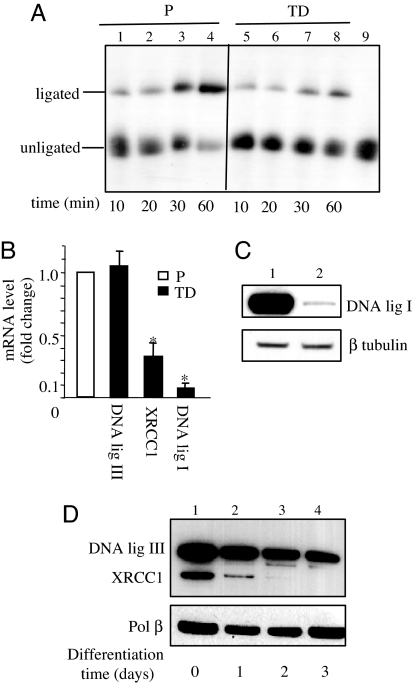

The incision of the abasic site by the major 5′ AP endonuclease APE1 and the resynthesis step by DNA polymerase β (Pol β) are unaffected by the differentiation state, as determined by functional assays, gene expression, and protein levels (SI Fig. 8). In contrast, when the ligation capacity of the two cell extracts was assessed, a significant difference between proliferating and terminally differentiated cells was detected by using a DNA ligase assay (Fig. 5A). This assay mainly reflects the activity of DNA ligase I and is in line with the dramatic decrease in transcription (Fig. 5B) and protein levels (Fig. 5C) of this enzyme observed in myotubes. DNA ligase I is required to seal Okazaki fragments during DNA replication and participates in BER. This last function is shared with the DNA ligase IIIα/XRCC1 heterodimer. RT-PCR analysis of DNA ligase III and XRCC1 (Fig. 5B) revealed that the transcription of XRCC1, but not of DNA ligase IIIα, was heavily down-regulated in myotubes. Western blotting analysis showed that both XRCC1 and DNA ligase IIIα protein levels dropped during differentiation (Fig. 5D) in a coordinated manner, as expected from the requirement of XRCC1 for the stability of DNA ligase IIIα (13).

Fig. 5.

Efficiency of the ligation step of cell extracts from proliferating and terminally differentiated muscle cells. (A) DNA ligation assay. Duplex oligonucletides containing a single nick were incubated with 40 μg of whole-cell extracts. The 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotide was the single nick-containing strand. The products were separated by electrophoresis on 12% urea denaturing polyacrylamide gels. Ligation reactions with extracts of myoblasts (lanes 1–4) and myotubes (lanes 5–8) for 10, 20, 30, and 60 min; lane 9, unligated oligonucleotide. Three independent extracts per cell type were tested. (B) Expression of DNA ligase I, XRCC1, and DNA ligase IIIα. mRNA levels were determinated by RT-PCR, and values were normalized (myoblast value is set at 1). Error bars indicate standard deviations (*, P < 0.001). (C) DNA ligase I and β-tubulin protein levels in myoblasts (lane 1) and myotubes (lane 2). (D) XRCC1 and DNA ligase IIIα protein levels in nuclear extracts from muscle cells at the indicated times (days) after addition of differentiation medium. DNA polymerase β protein levels were used as a loading control.

These findings underscore the key role played by DNA ligases and XRCC1 in the efficiency of BER in terminally differentiated cells, indicating that XRCC1 is down-regulated upon cell cycle withdrawal during differentiation.

Myotubes Accumulate Unrepaired DNA Damage After Oxidative Stress.

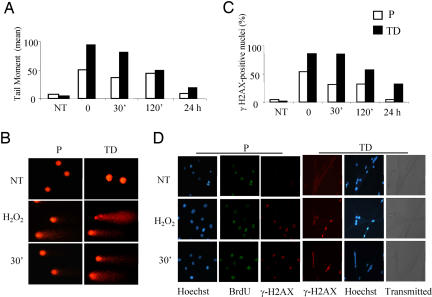

To gain insights into the biological relevance of the decrease in BER activity associated with muscle terminal differentiation, we explored the response to oxidative stress of proliferating versus terminally differentiated cells. Cells were exposed to H2O2, and the formation and repair of DNA SSB and alkali-labile sites (mainly abasic sites) were measured by the comet assay. The tail moment (TM) that reflects the frequency of breaks was used to quantify DNA damage. In myotubes, the level of damage induced by 30-min exposure to 100 μM H2O2 was significantly higher than in myoblasts and persisted for longer times (Fig. 6 A and B). The distribution of proliferating and terminally differentiated cell population by DNA damage classes (according to TM values) is provided in SI Fig. 9. Similar results were obtained after 30-min exposure to 50 μM H2O2 (data not shown). Unrepaired SSB are expected to be converted into double-strand breaks (DSB) at replication. Histone H2AX is rapidly phosphorylated in the chromatin microenvironment surrounding a DSB (14). The formation and repair of γH2AX foci were evaluated. The number of foci-positive nuclei immediately after 30-min treatment was significantly higher in myotubes than in myoblasts exposed to 100 μM H2O2 (Fig. 6C). The percentage of damaged nuclei gradually declined during the posttreatment repair time in both cell types, but with slower kinetics in terminally differentiated, compared with proliferating, cells. Similar results were obtained after 30-min exposure to 1 mM H2O2 (data not shown). Interestingly, γH2AX foci were present in proliferating cells exclusively in S-phase cells (BrdU-stained), which suggests that they identify DSB arising at replication from unrepaired SSB (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Induction of DNA SSB and γH2AX foci after H2O2 treatment of proliferating and terminally differentiated muscle cells. Myoblasts and myotubes were exposed to 100 μM H2O2 for 30 min and analyzed at different times after damage. (A) DNA SSB induction and repair as detected by the comet assay. The average of the tail moment (TM) of at least 100 cells per experimental point is shown. The distribution of comets by TM is provided as SI Fig. 7. (B) Microphotographs of proliferating (P) and terminally differentiated (TD) cells subjected to the comet assay and stained with ethidium bromide. Representative cells untreated (NT), immediately after damage (H2O2), and after 30-min repair are shown. (C) DNA damage induction and repair as detected by γH2AX foci formation. For each time point, at least 200 nuclei were examined. (D) The microphotographs show examples of myoblasts and myotubes stained with anti-γH2AX antibody alone or in combination with anti-BrdU antibody and counterstained with Hoechst. Representative cells untreated (NT), immediately after damage (H2O2), and after 30-min repair are shown. Experiments were repeated twice at two different doses (see Materials and Methods), and one representative experiment for each assay is shown.

These results indicate that, under free radical injury, repair intermediates arising from the processing of oxidative DNA damage accumulate in terminally differentiated muscle cells, as expected from the impaired BER/SSBR as detected in vitro.

Discussion

Here we provide evidence that myotubes are impaired in their ability to perfom BER of abasic sites, and we identify the molecular defects that involve DNA ligases and the scaffold protein, XRCC1. The lack of DNA ligase I, as well as the decreased levels of XRCC1 and DNA ligase IIIα, provide a mechanistic rationale for the reduced levels of both short- and long-patch BER in myotubes. Down-regulation of DNA ligase I, PCNA, Flap endonuclease-1 (FEN-1), and replicative DNA polymerases δ/ε are expected during the genome reprogramming toward differentiation known to involve repression of cell proliferation-associated genes (8). Long-patch repair synthesis is PCNA-dependent and involves FEN-1. The replicative DNA polymerases (2) and DNA ligase I have been shown to be indispensable for the resealing step (15, 16). Therefore, changes in the gene expression of these key players of long-patch BER are likely to account for the impairment of this pathway in myotubes. XRCC1 is critical for the in vivo stabilization of the DNA ligase IIIα protein (13). Accordingly, a decrease in DNA ligase IIIα levels was detected during the muscle differentiation process. XRCC1 plays a crucial role in the coordination of BER and SSBR because of its multiple interactions with other repair proteins (17). In addition to DNA ligase IIIα, XRCC1 interacts with several enzymes involved in BER/SSBR pathways, including APE1, Pol β, PNK, PCNA, and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 and 2. Therefore, XRCC1 is not only involved in the ligation step of BER/SSBR, but also in earlier repair steps. This finding would explain the accumulation of repair intermediates (incision and repair synthesis products) observed in terminally differentiated myotubes that are likely to represent echoes of defective loading of the BER machinery due to low levels of XRCC1 or defective ligation.

XRCC1 down-regulation in terminally differentiated cells might underscore the coregulation of cell cycle genes and XRCC1 expression. It has been demonstrated recently (18) that the transcription factor Forkhead Box M1 (FoxM1), which regulates the expression of cell cycle genes, has a role in XRCC1 expression. FoxM1-deficient cells display increased DNA breaks and reduced expression of XRCC1.

Among repair pathways, NER has been the most extensively analyzed during differentiation. NER was found to be generally repressed in terminally differentiated cells while remaining proficient in active genes (3, 4). Regulation at the level of the ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 was recently proposed as a strategy to coordinate the NER and other changes occurring during differentiation (19). Our study provides the first mechanistic analysis of the decreased BER activity of differentiated cells. The analysis of the regulation of BER during differentiation should be the challenge for future studies.

What is the biological significance of reduced BER in myotubes? XRCC1 mutant mouse embryos, which die at embryonic day 6.5 (20), were reported to accumulate unrepaired SSB in the egg cylinder and presented a high frequency of spontaneous sister chromatid exchanges. It has been hypothesized that the stage-specificity for embryo lethality in the absence of XRCC1 is caused by the high level of ROS due to increased metabolic activity during gastrulation. We provide evidence that in muscle cells the antioxidant cell response is altered during differentiation and may potentiate damage by the ROS produced during this process. In myotubes, this result increases endogenous oxidative DNA damage, indicated by the increase in 8-OH-Gua content. The endogenous ROS effects are limited, as shown by the relatively low levels of spontaneous DNA SSB and γH2AX foci, which are comparable to those of proliferating myoblasts. However, under increased free radical injury, DNA repair capacity becomes the limiting factor in the protection of genome integrity. Upon exposure to hydrogen peroxide, myotubes that are characterized by decreased XRCC1 levels and impaired DNA ligase activity accumulate DNA lesions as shown by the significantly higher frequency and persistence of both DNA SSB and γH2AX-positive nuclei, compared with proliferating cells. What is the identity of these lesions? After oxidative DNA damage, SSB are generated either directly by ROS or as repair intermediates during BER/SSBR. The comet assay reveals the presence of SSB and abasic sites induced by H2O2. As expected, their repair is rapid in proliferating cells, but delayed in myotubes characterized by inefficient BER/SSBR. The interpretation of γH2AX foci formation is more complex. Phosphorylation of H2AX is an early event in the ATM-dependent DNA damage-signaling pathway, which has been shown to be active in both myoblasts and myotubes after induction of DSB by ionizing radiation exposure (21). Evidence is accumulating that γH2AX foci also identify DNA damage-containing structures other than DSB (22). In the case of myoblasts, γH2AX foci were exclusively present in S-phase cells, indicating that they mark the formation of DSB produced by the replication of DNA templates containing SSB. In myotubes, which are unable to replicate, γH2AX foci are likely to signal the persistence of SSB-containing DNA structures due to attenuated BER/SSBR activity.

Recently, defects in SSBR involving accumulation of abortive DNA repair intermediates have been described in association with neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., several ataxias) (5, 6). Brain and muscle have a high rate of oxygen metabolism that might exacerbate a defect in DNA break repair in nonproliferating, terminally differentiated systems that are deprived of long-patch BER (this study), as well as of alternative replication-associated repair mechanisms such as homologous recombination.

In muscle cells after injury, satellite cells are stimulated to replace dead cells by replicating, but depletion of this reservoir has been reported during aging (23) and pathological conditions (24). During the aging process, ROS production may drastically increase because of altered function of the respiratory chain and insufficient levels of the cellular antioxidant defenses. Such an oxidative insult, combined with a less efficient BER system and the lack of postmitotic repair processes, might play a key role in the age-related decrease of muscle performance and mass (sarcopenia) and in muscle disorders associated with free radical overproduction.

Materials and Methods

For more details, see SI Materials and Methods.

Cells and Growth Conditions.

Murine skeletal muscle satellite cells were isolated, cultured, and differentiated as described previously (14).

Cell Extracts.

Whole-cell extracts for BER assays (Tanaka type) were prepared as described (27). Nuclear cell extracts for Western blot analysis were prepared by resuspending cells in ipotonic buffer. To compensate for the higher protein content of myotubes than myoblasts, samples in all assays were normalized so that lysates of cells possessed the same total number of nuclei.

Plasmid Assays.

pGEM-3Zf (+) plasmid DNA molecules containing a site-specific AP site were constructed as previously described (25). The plasmids containing the lactone precursor residue (1′-t-butylcarbonyluridylate) were constructed as described (12). Repair of the plasmid DNA containing a regular abasic site or a lactone residue (pGEM-AP/dL) was conducted as described (25). All experiments were repeated at least three times, and representative experiments are shown.

Ligation Assay.

Two oligonucleotides, a [γ-32P]ATP-5′-end labeled 30 nt and a 31 nt, were annealed to a 61-nt complementary strand to obtain duplex DNA molecules bearing a single nick. The incubation buffer was the same described for the BER plasmid assays.

Western Blot Analysis.

Proteins were separated on 4–12% polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by Western blotting with the following antibodies: monoclonal antibodies to DNA Ligase I (a gift of A. Montecucco, Institute of Molecular Genetics, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Pavia, Italy), DNA Ligase III (BD Biosciences PharMingen, San Diego, CA), XRCC1 (a gift of K. Caldecott, Genome Damage and Stability Center, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton, U.K.), polyclonal antibodies to Pol β (a gift of S. H. Wilson, Laboratory of Structural Biology, National Institutes of Health, Research Triangle Park, NC), and Ref1 (APE1) (sc-334; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Western blots were developed by using the West Dura kit (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL).

Measurement of Gene Expression.

Total RNA was isolated from myoblasts and myotubes by using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The expression levels of selected genes were measured by quantitative RT-PCR using primers pairs designed by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Measurement of 8-Hydroxyguanosine by HPLC/ED.

DNA levels of 8-hydroxyguanosine were measured by HPLC with electrochemical detection as described previously (26).

Cell Treatment and Analysis of DNA Damage.

Myoblasts and myotubes were treated with various doses of hydrogen peroxide for 30 min at 37°C (50 and 100 μM in the case of the comet assay, 100 μM and 1 mM in the case of the γH2AX foci assay) and harvested at different periods of time. DNA breaks were measured by the comet assay as previously described (27) with minor modifications. The analysis of γH2AX foci was performed by incubating cells with mouse monoclonal anti-γH2AX antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) alone or in combination with Alexa488-conjugated anti-BrdU (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 dye. Only nuclei showing 10 bright foci were considered positive.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Caldecott, S. H. Wilson, and A. Montecucco for providing antibodies specific for DNA repair proteins; and M. Minetti and D. Pietraforte for useful suggestions. This work was supported by a Federazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro fellowship (to L.N.), Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca/Fondo per gli Investimenti della Ricerca di Base) Grant RBNE01RNN7, Compagnia di San Paolo, Centers for Medical Countermeasures Against Radiation, Educational CORE Grant 5U19-A1067751-2 (to P.L.), and National Institutes of Health Grant GM40000 (to B.D.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0701743104/DC1.

References

- 1.Shi X, Garry DJ. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1692–1708. doi: 10.1101/gad.1419406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fortini P, Dogliotti E. DNA Repair. 2007;6:398–409. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nouspikel TP, Hanawalt PC. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1562–1570. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1562-1570.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nouspikel TP, Hyka-Nouspikel N, Hanawalt PC. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8722–8730. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01263-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Khamisy SF, Saifi GM, Weinfeld M, Johansson F, Helleday T, Lupski JR, Caldecott KW. Nature. 2005;434:108–113. doi: 10.1038/nature03314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahel I, Rass U, El-Khamisy SF, Katyal S, Clements PM, McKinnon PJ, Caldecott KW, West SC. Nature. 2006;443:713–716. doi: 10.1038/nature05164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okazaki K, Holtzer H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1966;56:1484–1490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.56.5.1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tiainen M, Pajalunga D, Ferrantelli F, Soddu S, Salvatori G, Sacchi A, Crescenzi M. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:1039–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen X, Collier JM, Hlaing M, Zhang L, Delshad EH, Bristow J, Bernstein HS. Dev Dyn. 2003;226:128–138. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srisook K, Kim C, Cha YN. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1674–1687. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadal RC, Abdelraheim SR, Brazier MW, Rigby SE, Brown DR, Viles JH. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sung JS, DeMott MS, Demple B. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39095–39103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506480200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caldecott KW, McKeown CK, Tucker JD, Ljungquist S, Thompson LH. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:68–76. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogakou EP, Boon C, Redon C, Bonner WM. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:905–916. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sleeth KM, Robson RL, Dianov GL. Biochemistry. 2004;43:12924–12930. doi: 10.1021/bi0492612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cappelli E, Taylor R, Cevasco M, Abbondandolo A, Caldecott K, Frosina G. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23970–23975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caldecott KW. DNA Repair. 2007;6:443–453. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan Y, Raychaudhuri P, Costa RH. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1007–1016. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01068-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nouspikel T, Hanawalt PC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16188–16193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607769103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tebbs RS, Flannery ML, Meneses JJ, Hartmann A, Tucker JD, Thompson LH, Cleaver JE, Pedersen RA. Dev Biol. 1999;208:513–529. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Latella L, Lukas J, Simone C, Puri PL, Bartek J. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6350–6361. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6350-6361.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu Y, Zhu W, Diao H, Zhou C, Chen FF, Yang J. Toxicol In Vitro. 2006;20:959–965. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marzetti E, Leeuwenburgh C. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:1234–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawke TJ, Garry DJ. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:534–551. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frosina G, Cappelli E, Ropolo M, Fortini P, Pascucci B, Dogliotti E. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;314:377–396. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-973-7:377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Degan P, Sancandi M, Zunino A., Ottaggio L, Viaggi S, Cesarone F, Pippia P, Galleri G, Abbondandolo A. J Cell Biochem. 2005;94:460–469. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fortini P, Pascucci B, Belisario F, Dogliotti E. Nucl Acids Res. 2000;28:3040–3046. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.16.3040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.