Abstract

Digestive trypsins undergo proteolytic breakdown during their transit in the human alimentary tract, which has been assumed to occur through trypsin-mediated cleavages, termed autolysis. Autolysis was also postulated to play a protective role against pancreatitis by eliminating prematurely activated intrapancreatic trypsin. However, autolysis of human cationic trypsin is very slow in vitro, which is inconsistent with the documented intestinal trypsin degradation or a putative protective role. Here we report that degradation of human cationic trypsin is triggered by chymotrypsin C, which selectively cleaves the Leu81-Glu82 peptide bond within the Ca2+ binding loop. Further degradation and inactivation of cationic trypsin is then achieved through tryptic cleavage of the Arg122-Val123 peptide bond. Consequently, mutation of either Leu81 or Arg122 blocks chymotrypsin C-mediated trypsin degradation. Calcium affords protection against chymotrypsin C-mediated cleavage, with complete stabilization observed at 1 mM concentration. Chymotrypsin C is highly specific in promoting trypsin degradation, because chymotrypsin B1, chymotrypsin B2, elastase 2A, elastase 3A, or elastase 3B are ineffective. Chymotrypsin C also rapidly degrades all three human trypsinogen isoforms and appears identical to enzyme Y, the enigmatic trypsinogen-degrading activity described by Heinrich Rinderknecht in 1988. Taken together with previous observations, the results identify chymotrypsin C as a key regulator of activation and degradation of cationic trypsin. Thus, in the high Ca2+ environment of the duodenum, chymotrypsin C facilitates trypsinogen activation, whereas in the lower intestines, chymotrypsin C promotes trypsin degradation as a function of decreasing luminal Ca2+ concentrations.

Keywords: chronic pancreatitis, digestive enzymes, trypsinogen degradation

Trypsinogen is the most abundant digestive proteolytic proenzyme in the pancreatic juice. In humans, trypsinogen is secreted in three isoforms, cationic trypsinogen, anionic trypsinogen, and mesotrypsinogen. Cationic trypsinogen (≈50–70%) and anionic trypsinogen (≈30–40%) make up the bulk of trypsinogens in the pancreatic juice, whereas mesotrypsinogen accounts for 2–10% (1–5). Physiological activation of trypsinogen to trypsin in the duodenum is catalyzed by enteropeptidase (enterokinase), a highly specialized serine protease in the brush-border membrane of enterocytes. Trypsin can also activate trypsinogen, in a process termed autoactivation, which facilitates zymogen activation in the duodenum.

A pathological increase in trypsin activity in the pancreatic acinar cells is one of the early events in the development of pancreatitis (ref. 6 and references therein). Inactivation of intrapancreatic trypsin through trypsin-mediated trypsin degradation (autolysis) or by an unidentified serine protease (enzyme Y) was therefore proposed to be protective against pancreatitis (7–11). This notion received support from the discovery that the R122H mutation, which eliminates the Arg122 autolytic site in cationic trypsinogen, causes autosomal dominant hereditary pancreatitis in humans (9). Autolytic cleavage of the Arg122-Val123 peptide bond was suggested to trigger rapid trypsin degradation by increasing structural flexibility and exposing further tryptic sites (10). Autolysis was also proposed to play an essential role in physiological trypsin degradation in the lower intestines. A number of studies in humans have demonstrated that trypsin becomes inactivated during its intestinal transit, and in the terminal ileum only ≈20% of the duodenal trypsin activity is detectable (12–14). On the basis of in vitro experiments, a theory was put forth that digestive enzymes are generally resistant to each other and undergo degradation through autolysis only (10, 15). However, human cationic trypsin was shown to be highly resistant to autolysis, and appreciable autodegradation was observed only with extended incubation times in the complete absence of Ca2+ and salts (16–18). Furthermore, we demonstrated that tryptic cleavage of the Arg122-Val123 peptide bond in human cationic trypsin(ogen) does not result in rapid degradation. Instead, due to trypsin-mediated resynthesis of the peptide bond, a dynamic equilibrium is reached between the single-chain (intact) and double-chain (cleaved) forms, which are functionally equivalent (19). Taken together, the in vitro studies indicate that autolysis alone cannot be responsible for the inactivation and degradation of human cationic trypsin and suggest that other pancreatic enzymes might be important in this process.

Recently, we serendipitously discovered that a minor human chymotrypsin, chymotrypsin C, regulates autoactivation of human cationic trypsinogen by limited proteolysis of the trypsinogen activation peptide (20). These experiments focused our attention onto this less-known chymotrypsin, and we characterized its interaction with human cationic trypsin in more detail. Surprisingly, we found that at low Ca2+ concentrations, chymotrypsin C cleaves a peptide bond with high selectivity within the Ca2+ binding loop of cationic trypsin, which results in rapid degradation and loss of trypsin activity. The observations suggest that chymotrypsin C may be the long-elusive digestive enzyme responsible for trypsin degradation in the gut and may serve as a protective protease in the pancreas to curtail premature trypsin activation. In this study, compelling evidence is presented in support of this contention.

Results

Chymotrypsin C Promotes Degradation of Human Cationic Trypsin.

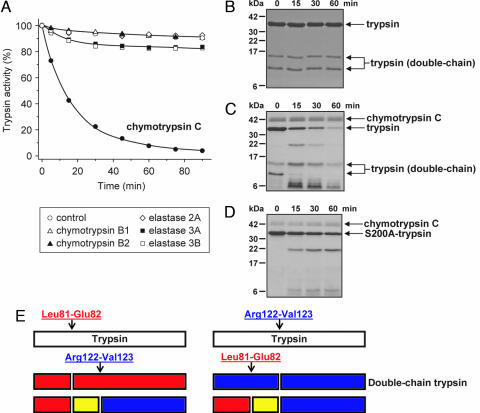

Incubation of human cationic trypsin with chymotrypsin C at pH 8.0 and at 37°C in the presence of 25 μM Ca2+ resulted in rapid loss of trypsin activity, with a t½ of ≈15 min (Fig. 1A). Under these conditions, autocatalytic degradation (autolysis) of cationic trypsin was negligible. Degradation of cationic trypsin by chymotrypsin C proved to be highly specific, because chymotrypsin B1, chymotrypsin B2, elastase 2A, elastase 3A, or elastase 3B had no significant degrading activity at pH 8.0 (Fig. 1A) or at pH 6.0 (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Degradation of human cationic trypsin by chymotrypsin C. (A) Cationic trypsin (2 μM) was incubated alone (control) or with 300 nM of the indicated proteases in 0.1 M Tris·HCl (pH 8.0) and 25 μM CaCl2 (final concentrations) in 100 μl of final volume. At the indicated times, 2-μl aliquots were withdrawn, and residual trypsin activity was measured and expressed as a percentage of the initial activity. (B–D) SDS/PAGE analysis of autolysis and chymotrypsin C-mediated degradation of cationic trypsin. Wild-type cationic trypsin (B and C) or S200A mutant cationic trypsin (D) were incubated at 2 μM concentration in the absence (B) or presence (C and D) of 300 nM chymotrypsin C in 0.1 M Tris·HCl (pH 8.0) and 25 μM CaCl2 (final concentrations). At the indicated times, 100-μl aliquots were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid (final concentration) and electrophoresed on 15% minigels under reducing conditions, followed by Coomassie blue staining. Note that chymotrypsin C is glycosylated and runs as a fuzzy band. Double-chain trypsin is cleaved at the Arg122-Val123 peptide bond and runs as two bands on reducing gels; the upper band corresponds to the C-terminal chain (Val123-Ser247), and the lower band is the N-terminal chain (Ile24-Arg122). (E) Major proteolytic cleavage sites in cationic trypsin determined from N-terminal sequencing of the visible bands in C.

SDS/PAGE analysis of the spontaneous autolysis reaction of cationic trypsin showed no appreciable degradation over the 1 h time course studied (Fig. 1B). As described in ref. 19, human cationic trypsin consists of an equilibrium mixture of single-chain and double-chain forms cleaved at the Arg122-Val123 peptide bond, and both forms remained stable under the experimental conditions. In stark contrast, when chymotrypsin C was included in the reaction, SDS/PAGE showed the time-dependent disappearance of both the single-chain and double-chain trypsin bands and the appearance of degradation fragments, which were eventually further degraded to peptides too small to resolve on the 15% gels used (Fig. 1C). Surprisingly, when a catalytically inactive Ser200 → Ala (S200A) cationic trypsin mutant was digested with chymotrypsin C, the overall rate of trypsin degradation was markedly slower, indicating that trypsin activity is required for efficient chymotrypsin C-mediated cationic trypsin degradation (Fig. 1D).

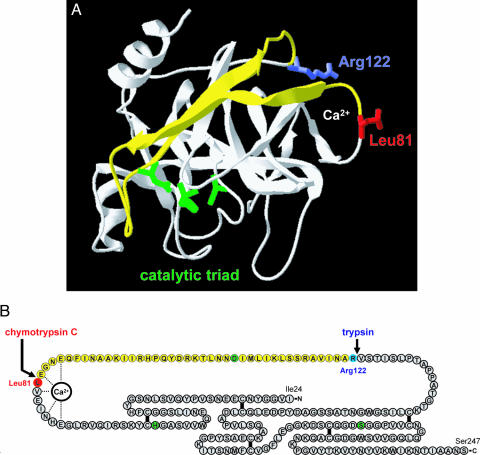

N-terminal sequencing of the visible bands in Fig. 1C revealed that the primary chymotrypsin C cleavage site was the Leu81-Glu82 peptide bond within the Ca2+ binding loop of cationic trypsin (Figs. 1E and 2). The C-terminal chymotryptic fragment (Glu82-Ser247) underwent rapid tryptic (autolytic) cleavage at the Arg122-Val123 peptide bond, resulting in three peptides, corresponding to the Ile24-Leu81; Glu82-Arg122 and Val123-Ser247 segments (see Figs. 1E and 2). The same three peptides were generated when chymotrypsin C cleaved the Leu81-Glu82 peptide bond in the double-chain cationic trypsin, already cleaved after Arg122. Finally, a peptide generated in low yields by chymotryptic cleavage of the Leu41-Asn42 peptide bond was also identified among the lower molecular weight bands (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 2.

Structural determinants of chymotrypsin C-mediated trypsin degradation. (A) Ribbon diagram of human cationic trypsin [Protein Data Bank ID code 1TRN; chain B of the crystallographic dimer shown here (21)] with the Leu81 (red) and Arg122 (blue) side chains indicated. The calcium-binding loop is denoted by the Ca2+ symbol. The catalytic triad consisting of His63 (His57 in the conventional chymotrypsin numbering); Asp107 (chymotrypsin no. Asp102) and Ser200 (chymotrypsin no. Ser195) are shown in green. Note that Asp107 is located on the yellow peptide segment, which is released upon cleavage of the Leu81-Glu82 and Arg122-Val123 peptide bonds. See text for details. The image was rendered using DeepView/Swiss-PdbViewer version 3.7. (B) Primary structure of human cationic trypsin. Individual amino acids are represented by circles. The catalytic triad is highlighted in green, Leu81 is in red, and Arg122 is in blue. The five disulfide bridges and the interactions between the calcium ion and amino acids within the calcium binding loop are indicated. Note that both the Leu81-Glu82 and the Arg122-Val123 peptide bonds are located in a long peptide segment not stabilized by disulfide bonds. The yellow section corresponds to the yellow peptide in A.

Ca2+ Protects Cationic Trypsin Against Chymotrypsin C-Mediated Degradation.

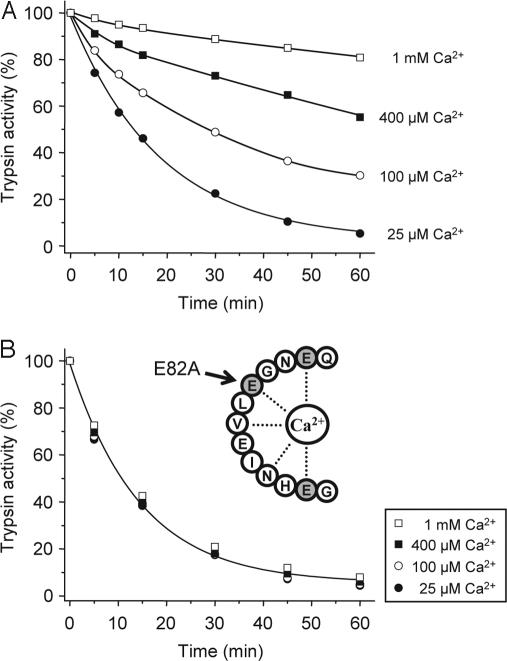

Because the primary chymotrypsin C cleavage site is located within the calcium binding loop of cationic trypsin (see Fig. 2), we speculated that Ca2+ might be protective against chymotryptic cleavage and subsequent trypsin degradation. Indeed, increasing the Ca2+ concentration from 25 μM to 1 mM progressively inhibited the degradation of cationic trypsin by chymotrypsin C, with essentially complete protection observed at 1 mM Ca2+ (Fig. 3A). The half-maximal protective Ca2+ concentration was 40 μM, which probably corresponds to the Kd of Ca2+ binding to cationic trypsin. As shown in supporting information (SI) Fig. 7, inhibition of trypsin degradation by Ca2+ was also quantified at pH 6.0, and a half-maximal protective concentration of 90 μM was obtained. To demonstrate that the protective effect of Ca2+ is exerted through binding to the Ca2+ binding loop in trypsin, we mutated Glu82 to Ala (E82A). Glu82 is one of three carboxylate side chains that bind the Ca2+ ion (Fig. 2B). In 25 μM Ca2+, both the E82A mutant (Fig. 3B) and the corresponding wild-type (Fig. 3A) cationic trypsins were degraded by chymotrypsin C with similar kinetics, indicating that Glu82 is not essential for efficient chymotrypsin C cleavage. Remarkably, however, degradation of E82A-trypsin was insensitive to Ca2+ up to 1 mM concentrations, confirming that an intact Ca2+ binding site in trypsin is required for the protective effect of Ca2+ against chymotrypsin C.

Fig. 3.

Effect of calcium on the chymotrypsin C-mediated degradation of human cationic trypsin. Wild-type cationic trypsin (A) or the E82A mutant (B) were incubated at 2 μM concentration with 300 nM chymotrypsin C (final concentration) in 0.1 M Tris·HCl (pH 8.0) and the indicated CaCl2 concentrations. At the given times, residual trypsin activity was determined as described in Fig. 1A.

Both Chymotryptic Cleavage After Leu81 and Autolytic Cleavage After Arg122 Are Required for Degradation of Cationic Trypsin.

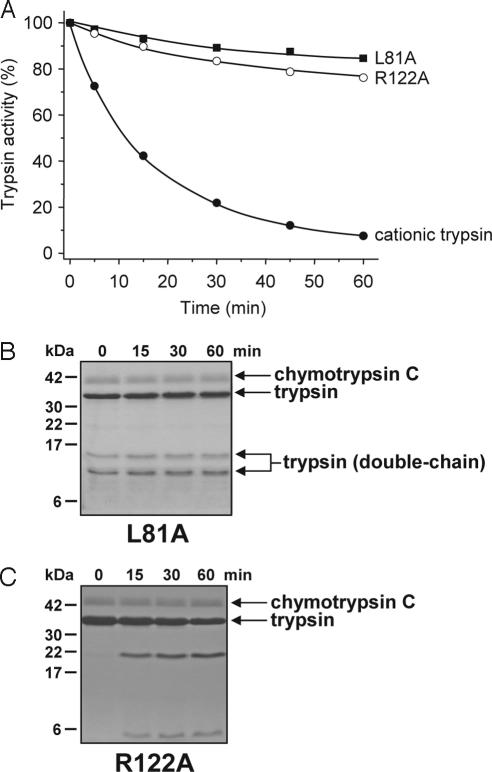

To investigate the relative significance of the chymotryptic cleavage after Leu81 and the autolytic cleavage after Arg122, both sites were mutated to Ala individually, and the L81A and R122A mutant cationic trypsins were digested with chymotrypsin C. Strikingly, both mutations afforded essentially complete protection against chymotrypsin C-mediated degradation (Fig. 4A). SDS/PAGE analysis confirmed that mutant L81A remained intact in the presence of chymotrypsin C, with both single-chain and double-chain trypsin species unaffected (Fig. 4B). The R122A mutant was slowly cleaved by chymotrypsin C at a rate that was similar to the chymotryptic cleavage of the S200A-trypsin in Fig. 1D (Fig. 4C). However, in the absence of autolytic cleavage at the Arg122-Val123 peptide bond, this slow chymotryptic cleavage was insufficient to produce appreciable degradation. Although not shown, mutation R122H protected against chymotrypsin C-mediated trypsin degradation as well as mutation R122A. Taken together, the results indicate that chymotryptic cleavage of the Leu81-Glu82 peptide bond and autolytic cleavage of the Arg122-Val123 peptide bond are both essential for rapid trypsin degradation.

Fig. 4.

Mutations L81A and R122A stabilize cationic trypsin against chymotrypsin C-mediated degradation. Wild-type, L81A, and R122A cationic trypsins were incubated at 2 μM concentration with 300 nM chymotrypsin C in 0.1 M Tris·HCl (pH 8.0) and 25 μM CaCl2 (final concentrations). (A) At the indicated times, residual trypsin activity was measured as described in Fig. 1A. (B and C). Aliquots (100 μl) were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid (final concentration) and analyzed by SDS/15% PAGE under reducing conditions.

Chymotrypsin C Is Identical to Enzyme Y, the Trypsinogen Degrading Activity from Human Pancreatic Juice.

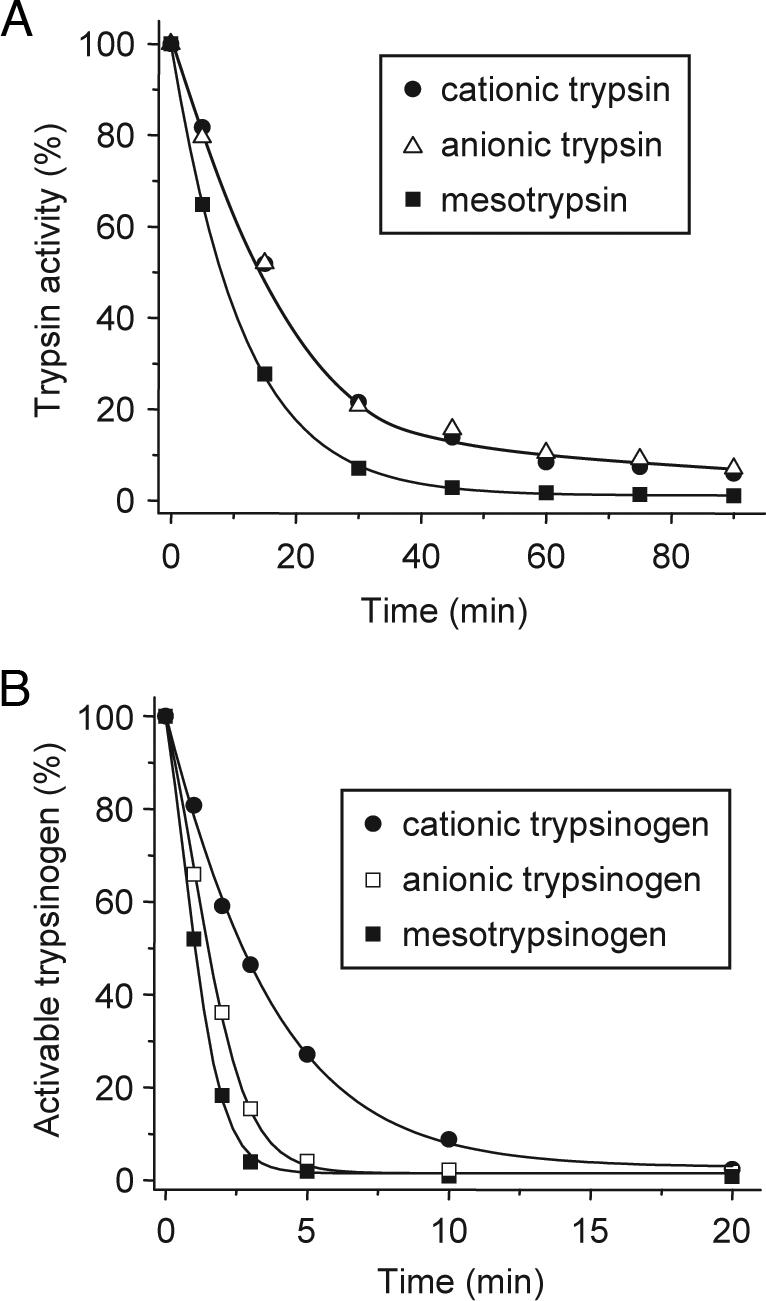

On the basis of its ability to degrade human cationic trypsin with high specificity and in a Ca2+-dependent manner, we speculated that chymotrypsin C might be identical to enzyme Y, the trypsinogen-degrading enzymatic activity isolated from human pancreatic juice by Heinrich Rinderknecht in 1988 (see Discussion for more on enzyme Y) (8). Consistent with this assumption, chymotrypsin C was capable of degrading not only cationic trypsin but also anionic trypsin and mesotrypsin (Fig. 5A), as well as the trypsin precursors cationic trypsinogen, anionic trypsinogen, and mesotrypsinogen (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, trypsinogen degradation proceeded significantly faster (t½ ≈ 2–5 min) than trypsin degradation. Millimolar Ca2+ concentrations inhibited trypsinogen degradation as well as trypsin degradation (data not shown). SI Fig. 8 demonstrates the degradation banding pattern of human trypsinogens on gels and the chymotrypsin C cleavage sites deduced from N-terminal sequencing of the visible bands. Although the Leu81-Glu82 peptide bond was readily cleaved in all three trypsinogens, additional isoform-specific chymotryptic cleavage sites were also observed.

Fig. 5.

Degradation of the three human trypsin and trypsinogen isoforms by chymotrypsin C. (A) Human cationic trypsin, anionic trypsin, and mesotrypsin were incubated at 2 μM concentration with 300 nM chymotrypsin C in 0.1 M Tris·HCl (pH 8.0) and 25 μM CaCl2 (final concentrations). At the indicated times, residual trypsin activity was measured as described in Fig. 1A. (B) Human cationic trypsinogen, anionic trypsinogen, and mesotrypsinogen (2 μM) were incubated with 300 nM chymotrypsin C in 0.1 M Tris·HCl (pH 8.0) and 25 μM CaCl2 (final concentrations). At the indicated times, 10-μl aliquots were withdrawn, CaCl2 was added to 10 mM final concentration and activable trypsinogen content was determined by incubating with 120 ng/ml human enteropeptidase for 15 min at room temperature and measuring trypsin activity. Activable trypsinogen was expressed as a percentage of the initial activable trypsinogen content.

Discussion

The present study identifies chymotrypsin C as the pancreatic digestive enzyme that can promote degradation and inactivation of human cationic trypsin. These results resolve the contradiction between the in vivo documented intestinal trypsin degradation (12–14) and the in vitro observed resistance of human cationic trypsin against autolysis (16–18) and strongly suggest that chymotrypsin C is responsible for the elimination of trypsin activity in the lower small intestines. Furthermore, the observations clearly negate the notion that degradation of digestive serine proteases is always autocatalytic in nature (15) and provide a clear example for heterolytic degradation. The specificity of chymotrypsin C in mediating trypsin degradation is striking. All other chymotrypsins and elastases tested were completely ineffective in this respect. Trypsin degradation is initiated by selective cleavage of the Leu81-Glu82 peptide bond within the Ca2+ binding loop, followed by trypsin-mediated autolytic cleavage of the Arg122-Val123 peptide bond. Millimolar Ca2+ concentrations inhibit chymotrypsin C-mediated cleavage after Leu81 by stabilizing the Ca2+ binding loop and thus protect against degradation.

Autolytic degradation of cationic trypsin was postulated to play a protective role in the pancreas against inappropriate trypsin activation (9–10). This assumption was based on the observation that human hereditary pancreatitis is associated with the R122H cationic trypsin mutation, which destroys the Arg122 autolytic site (9). However, the unusually high resistance of human cationic trypsin to autolysis in vitro has called into question the presumed protective role of trypsin autolysis and the proposed pathomechanism of the R122H mutation. Hereditary pancreatitis follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance and variable disease expression, and it is typically characterized by early onset episodes of acute pancreatitis with frequent progression to chronic pancreatitis and an increased risk for pancreatic cancer (9, 22). Besides mutation R122H, to date >20 other cationic trypsinogen variants have been identified in pancreatitis patients, but mutation R122H is responsible for the large majority of cases (≈70%) (22). The results presented here support a putative defense mechanism in which chymotrypsin C-mediated trypsin degradation mitigates unwanted intrapancreatic trypsin activity. The conditions at the site of intraacinar trypsinogen activation (pH ≈6.0, Ca2+ concentration ≈40 μM) are conducive for such a mechanism to be operational (23). Impairment of this mechanism by the R122H mutation may contribute to the pathogenesis of hereditary pancreatitis.

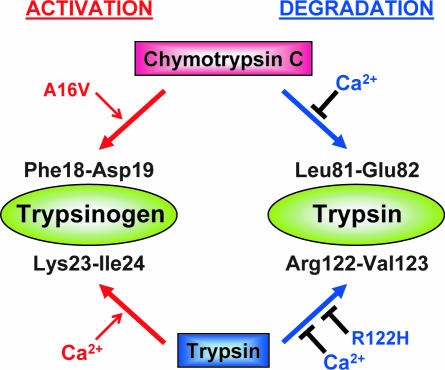

Chymotrypsin C was first isolated from pig pancreas and was shown to exhibit a preference for leucyl peptide bonds, which distinguished it from chymotrypsin A or chymotrypsin B (24, 25). Chymotrypsin C seems to be the same protein as caldecrin, a serum-calcium-decreasing protein isolated from porcine and rat pancreas and later cloned from rat and human pancreas (26, 27). Recently, we reported that chymotrypsin C regulates autoactivation of cationic trypsinogen through limited proteolysis of its activation peptide at the Phe18-Asp19 peptide bond (20). The N-terminally truncated cationic trypsinogen autoactivates 3-fold faster than its intact form. Taken together with these previous observations, the present results identify chymotrypsin C as a key regulator of trypsinogen activation and trypsin degradation in humans (Fig. 6). Thus, in the activation pathway, chymotrypsin C cleaves the Phe18-Asp19 bond in the trypsinogen activation peptide, which in turn facilitates tryptic cleavage of the Lys23-Ile24-activating peptide bond, resulting in increased autoactivation. In the degradation pathway, chymotrypsin C cleaves the Leu81-Glu82 peptide bond, and subsequent tryptic cleavage of the Arg122-Val123 peptide bond destines trypsin for degradation and inactivation. Clearly, chymotrypsin C accelerates already existing autoregulatory functions of cationic trypsin (i.e., autoactivation and autolysis). The balance between activation and degradation is regulated by the prevailing Ca2+ concentrations. In the presence of high Ca2+ concentrations (>1 mM) characteristic of the upper small intestines, the degradation pathway is blocked and trypsinogen activation is predominant. As the Ca2+ concentration falls below millimolar levels in the lower intestines, trypsin degradation prevails. Although intestinal Ca2+ absorption has been studied extensively, reliable data on the ionized Ca2+ concentrations along the small intestines is lacking (28). It is noteworthy that ionized Ca2+ concentrations in the gut are largely determined by luminal pH and insoluble complex formation, which becomes more significant at the more alkaline pH of the lower intestines, where trypsin degradation was shown to occur (29).

Fig. 6.

Chymotrypsin C stimulates trypsin-mediated trypsinogen activation (autoactivation) and trypsin-mediated trypsin degradation (autolysis). In the presence of millimolar Ca2+ concentrations, the trypsin degradation pathway is blocked and only the trypsinogen activation pathway is operational. Both pathways are affected by certain hereditary pancreatitis-associated mutations. Mutation A16V stimulates the activation pathway (20), whereas mutation R122H inhibits the degradation pathway. See text for details.

An unexpected bonus from these studies was the identification of chymotrypsin C as enzyme Y, a so-far obscure trypsinogen-degrading activity from human pancreatic juice. Enzyme Y was described by the late Heinrich Rinderknecht, the renowned pancreatologist, in 1988 (8). Rinderknecht was also the first to identify the inhibitor-resistant human mesotrypsin in 1984 (4). He initially alleged that mesotrypsin can degrade trypsinogens, but later he withdrew this conclusion and attributed the trypsinogen-degrading activity to an unidentified serine protease, which he named enzyme Y (7, 8). This enigmatic activity developed when human cationic trypsinogen, purified by native gel electrophoresis, was incubated at 37°C. This activity degraded all human trypsinogen isoforms, and millimolar Ca2+ concentrations blocked degradation. Enzyme Y became very popular among pancreas researchers and has been highlighted in almost every significant article discussing defense mechanisms against intrapancreatic trypsin activity. Rinderknecht himself believed that enzyme Y was probably a degradation fragment of cationic trypsin (8), perhaps complexed with pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (30), although he acknowledged the possibility of contamination with an unknown protease (8). The observations presented in this study seem fully consistent with the conclusion that chymotrypsin C is in fact enzyme Y, which contaminated the cationic trypsinogen preparations in Rinderknecht's experiments. Thus, chymotrypsin C is a serine protease, which can rapidly degrade all three human trypsinogens in a Ca2+-dependent manner. No other pancreatic protease tested in this study had trypsin- or trypsinogen-degrading activity. It is unlikely that chymotrypsin C-mediated trypsinogen degradation has any physiological role in digestion, as high Ca2+ concentrations in the duodenum would inhibit trypsinogen degradation and favor trypsinogen activation (see Fig. 6). However, Rinderknecht's theory that enzyme Y protects the pancreas by decreasing trypsinogen concentrations during inappropriate zymogen activation might be valid, and our present study should stimulate further research in this direction.

Methods

Nomenclature.

Amino acid residues in the trypsinogen sequence are numbered according to their position in the native preproenzyme, starting with Met1. The first amino acid of the mature cationic trypsinogen is Ala16.

Construction of Expression Plasmids and Expression and Purification of Digestive Proenzymes.

See SI Text for more information about expression plasmids and purification of digestive proenzymes.

Activation of Digestive Proenzymes.

Chymotrypsinogens and pro-elastases (1–5 μM concentration) were activated in 0.1 M Tris·HCl (pH 8.0) and 10 mM CaCl2 for 20 min at 37°C, with 100 nM cationic trypsin (final concentration), with the exception of pro-elastase 2A, which was activated with 100 nM anionic trypsin. Trypsinogens (2 μM concentration) were activated to trypsin with human enteropeptidase (28 ng/ml concentration) for 30 min at 37°C, in 0.1 M Tris·HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 mM CaCl2.

Enzymatic Assays.

Trypsin activity was measured with the synthetic chromogenic substrate, N-CBZ-Gly-Pro-Arg-p-nitroanilide (0.14 mM final concentration) in 200 μl final volume. One-minute time courses of p-nitroaniline release were followed at 405 nm in 0.1 M Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM CaCl2, at room temperature. To verify the activity of the other recombinant pancreatic enzymes, chymotrypsins were assayed with Suc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-p-nitroanilide (0.15 mM concentration), elastase 2A activity was measured with Glt-Ala-Ala-Pro-Leu-p-nitroanilide (1 mM concentration), and elastase 3A and 3B were assayed with DQ elastin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Béla Ózsvári, Vera Sahin-Tóth, and Zsófia Nemoda for help with some of the experiments. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK058088 (to M.S.-T.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0703714104/DC1.

References

- 1.Guy O, Lombardo D, Bartelt DC, Amic J, Figarella C. Biochemistry. 1978;17:1669–1675. doi: 10.1021/bi00602a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rinderknecht H, Renner IG, Carmack C. Gut. 1979;20:886–891. doi: 10.1136/gut.20.10.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheele G, Bartelt D, Bieger W. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:461–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rinderknecht H, Renner IG, Abramson SB, Carmack C. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:681–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rinderknecht H, Stace NH, Renner IG. Dig Dis Sci. 1985;30:65–71. doi: 10.1007/BF01318373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saluja AK, Lerch MM, Phillips PA, Dudeja V. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:249–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.031905.161253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rinderknecht H. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:314–321. doi: 10.1007/BF01318124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rinderknecht H, Adham NF, Renner IG, Carmack C. Int J Pancreatol. 1988;3:33–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02788221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitcomb DC, Gorry MC, Preston RA, Furey W, Sossenheimer MJ, Ulrich CD, Martin SP, Gates LK, Jr, Amann ST, Toskes PP, et al. Nat Genet. 1996;14:141–145. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Várallyay E, Pál G, Patthy A, Szilágyi L, Gráf L. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;243:56–60. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halangk W, Kruger B, Ruthenburger M, Sturzebecher J, Albrecht E, Lippert H, Lerch MM. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:G367–G374. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00315.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borgström B, Dahlqvist A, Lundh G, Sjovall J. J Clin Invest. 1957;36:1521–1536. doi: 10.1172/JCI103549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Layer P, Go VL, DiMagno EP. Am J Physiol. 1986;251:G475–G480. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1986.251.4.G475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bohe M, Borgström A, Genell S, Ohlsson K. Digestion. 1986;34:127–135. doi: 10.1159/000199321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bódi A, Kaslik G, Venekei I, Gráf L. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:6238–6246. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahin-Tóth M, Tóth M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:286–289. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szilágyi L, Kénesi E, Katona G, Kaslik G, Juhász G, Gráf L. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24574–24580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kukor Z, Tóth M, Sahin-Tóth M. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:2047–2058. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kukor Z, Tóth M, Pál G, Sahin-Tóth M. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6111–6117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nemoda Z, Sahin-Tóth M. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11879–11886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600124200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaboriaud C, Serre L, Guy-Crotte O, Forest E, Fontecilla-Camps J-C. J Mol Biol. 1996;259:995–1010. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teich N, Rosendahl J, Tóth M, Mössner J, Sahin-Tóth M. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:721–730. doi: 10.1002/humu.20343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherwood MW, Prior IA, Voronina SG, Barrow SL, Woodsmith JD, Gerasimenko OV, Petersen OH, Tepikin AV. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5674–5679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700951104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folk JE, Schirmer EW. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:181–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folk JE, Cole PW. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomomura A, Tomomura M, Fukushige T, Akiyama M, Kubota N, Kumaki K, Nishii Y, Noikura T, Saheki T. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30315–30321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomomura A, Yamada H, Fujimoto K, Inaba A, Katoh S. FEBS Lett. 2001;508:454–458. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bronner F. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:387–393. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duflos C, Bellaton C, Pansu D, Bronner F. J Nutr. 1995;125:2348–2355. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.9.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitcomb DC. Pancreas. 1999;18:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.