Abstract

The ε subunit of bacterial and chloroplast FoF1-ATP synthases modulates their ATP hydrolysis activity. Here, we report the crystal structure of the ATP-bound ε subunit from a thermophilic Bacillus PS3 at 1.9-Å resolution. The C-terminal two α-helices were folded into a hairpin, sitting on the β sandwich structure, as reported for Escherichia coli. A previously undescribed ATP binding motif, I(L)DXXRA, recognizes ATP together with three arginine and one glutamate residues. The E. coli ε subunit binds ATP in a similar manner, as judged on NMR. We also determined solution structures of the C-terminal domain of the PS3 ε subunit and relaxation parameters of the whole molecule by NMR. The two helices fold into a hairpin in the presence of ATP but extend in the absence of ATP. The latter structure has more helical regions and is much more flexible than the former. These results suggest that the ε C-terminal domain can undergo an arm-like motion in response to an ATP concentration change and thereby contribute to regulation of FoF1-ATP synthase.

Keywords: ATP hydrolysis, ATP-binding motif, ATPase regulation, ATP synthase, F1 rotation

The FoF1-ATP synthase is a multisubunit enzyme that catalyzes ATP synthesis driven by a transmembrane proton gradient generated through electron transport in mitochondria, bacterial plasma membranes, or photosynthetic organelles (1–4). This enzyme is composed of two components, i.e., water-soluble F1 and membrane-embedded Fo. The former includes catalytic sites, and the latter translocates protons across membranes. The simplest F1 comprises five kinds of subunits with a stoichiometry of α3β3γ1δ1ε1 and shows ATPase activity (5, 6). ATP hydrolysis induces F1 rotation, in which a central stalk formed from the γ and ε subunits rotates relative to the α3β3 ring (7–10).

The ε subunit is known as an endogenous inhibitor of the ATPase activity of F1 and FoF1 in bacteria and plants (11–13). Interestingly, it does not inhibit ATP synthesis by FoF1. The crystal (14) and solution (15) structures of the isolated ε from Escherichia coli (EF1ε) comprise two distinct domains, an N-terminal β-sandwich domain with 10 β-strands and a C-terminal domain (CTD) composed of two helices. The C-terminal helices are folded into a hairpin form sitting on top of the N-terminal domain (NTD). The same structure was found in the crystal structure of the δ subunit (equivalent to the bacterial ε subunit) of F1 from mitochondria (MF1) (16). The folded form is called the “down-state” because whole CTD is located at the bottom of the γ subunit (see Fig. 5). Several genetic and disulfide cross-linking analyses have revealed that NTD is required for the coupling of F1 and Fo (17–19), whereas CTD was believed to be involved in inhibition of ATPase activity (17, 18, 20). It was also suggested for F1ε to regulate energy coupling in FoF1 (21). Cross-linking experiments have shown that CTD interacts with multiple subunits of F1 (22–27). This observation cannot be explained by the down-state structure. Furthermore, several cross-linking experiments revealed that ε in the down state does not inhibit ATPase activity (28, 29). Thus, the conformation responsible for the inhibition of ATPase activity has been called the “up-state.”

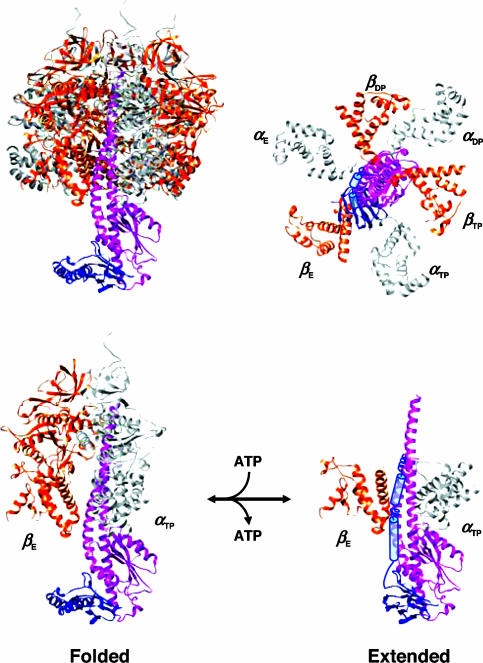

Fig. 5.

A model for the conversion between the up-extended and down-folded ε subunits in F1. (Upper Right) Top view (from the cytoplasmic side) of a model structure of the up-extended ε subunit in the α3β3γ complex on the basis of the crystal structure of the MF1 α3β3γδ complex (PDB ID code 1E79, Upper Left). Only N-terminal domain of MF1δ is shown. The C-terminal domain of TF1ε is represented by blue poles (stable helices in Fig. 3 B and C) and coils (flexible helices). Only C-terminal domains of the α and β subunits are depicted. (Lower Right) Side view from the bottom side of the top figure. (Lower Left) Side view of the folded ε. The rotation of the γε axle is clockwise on ATP hydrolysis.

The crystal structure of EF1 γ′ε complex (γ′: truncated-γ) indicated a different ε conformation, in which the C-terminal helices are extended and wind around the γ subunit (30). However, there is no direct evidence that the extended structure found in the crystal is responsible for ATPase inhibition. On the basis of a cross-linking (31) and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) (32) studies on F1 from thermophilic Bacillus strain PS3 (TF1), a CTD conformation fully extending along the axial helices of the γ subunit (up-extended conformation, hereafter) was suggested for the up-state. The efficiency of the conversion to the down-state was regulated by the ATP concentration and membrane potential. Actually, the isolated ε subunits of TF1 and Bacillus subtilis F1 were found to bind ATP (33, 34), suggesting the importance of ATP binding in regulation of the conformational change of ε. However, there have been no structural data on TF1ε so far.

To elucidate the mechanism of the conformational change in TF1ε CTD, and the role of ATP in conversion between the up and down states, we have determined the crystal structure of the isolated TF1 ε subunit with ATP, and the solution structures of the CTD in the absence and presence of ATP. The results provided clear evidence for binding of ATP to TF1ε and the conformational change from the extended to folded form of CTD on ATP binding.

Results

Crystal Structure of the TF1ε/ATP Complex at 1.9-Å Resolution.

The overall structure of TF1 ε is similar to that of EF1ε (14), as shown in Fig. 1A. The refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. The secondary structure elements are indicated in Fig. 2C. TF1ε is composed of two domains, namely, an N-terminal β sandwich (residues 1–84) and a C-terminal α-helical domain (90–133). A 310 helix (85–87) is inserted in the short loop linking the N- and C-terminal domains. The N-terminal domain (NTD) is composed of 10 β strands. Five strands (β1: 4–10, β2: 13–20, β5: 41–45, β8: 66–71, and β9: 74–79) form one antiparallel β sheet except for a parallel pair, β1 and β9, and the other five strands (β3: 22–27, β4: 30–34, β6: 47–54, β7: 57–64 and β10: 82–84) form another antiparallel β sheet. CTD comprises two α-helices (α1: 90–104 and α2: 113–130), and a short loop linking these α-helices. The hydrophobic contact surface between two helices is formed by an “alanine zipper”-like structure, as in the case of EF1ε. The relative orientation of NTD and CTD is slightly different for TF1ε and EF1ε. If TF1ε is superimposed on NTD of EF1ε, the CTD shows deviation by 8° [see supporting information (SI) Fig. 6]. When NTD and CTD of two ε subunits are superimposed independently, they fit well to each other except for the loop in CTD. Actually, the loop is poorly defined (B factor for the main chain, 49.7 Å2), which caused a relatively high rmsd of bond angles and Rfree in table 1. Also, the Asp-109 in this loop is the only residue found in the disallowed regions in the Ramachandran plot.

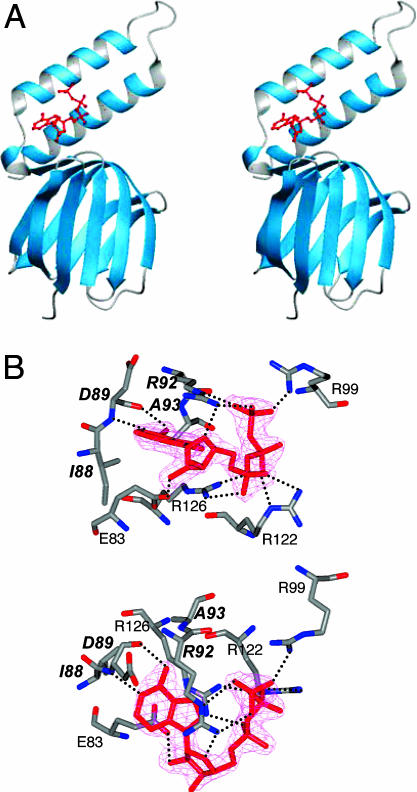

Fig. 1.

The crystal structure of the TF1ε subunit. (A) Stereoview of a ribbon diagram of the TF1ε/ATP complex. The bound ATP is colored red. (B) The omit-difference map of ATP (pink) and the residues involved in ATP binding. The bold symbols stand for the residues in the ATP binding motif. Possible hydrogen bond interactions are shown by dotted lines. (Upper and Lower) Side and top views, respectively.

Table 1.

Summary of refinement statistics

| Resolution range (outer shell), Å | 10.0–1.92 (1.968–1.920) |

| Reflections used | 17,451 (841) |

| No. of atoms | 2,309 |

| Protein/ATP/water | 2,042/62/205 |

| R factor/Rfree (%) | |

| With ATP | 19.9 (19.9)/24.9 (27.7) |

| Without ATP | 24.2 (22.6)/30.6 (31.4) |

| rmsd bond length, Å/bond angle, ° | 0.016/2.208 |

| Ramachandran plot statistics | |

| Most favored regions, % | 93.6 |

| Additional allowed regions, % | 5.6 |

| Generously allowed regions, % | 0.4 |

| Disallowed regions, % | 0.4 |

| Averaged B factor, Å2 | |

| Over all/protein | 29.9/29.5 |

| Main chain/side chain | 27.8 (49.7*)/31.4 (51.6*) |

| ATP/water | 19.7/36.0 |

| Wilson Plot | 23.4 |

*The value is only for the loop (105–112) region.

Fig. 2.

Effects of ATP on NMR spectrum and secondary structure of the TF1ε subunit. (A and B) 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the uniformly 15N labeled TF1ε at pH 6.8 and 30°C in the presence (A) and absence (B) of ATP, respectively. (C) Secondary structure elements commonly predicted on TALOS and CSD analyses along the primary sequence of TF1ε, which was update in 2000 (GenBank accession no. AB044942). The dotted lines show the helices based on TALOS. Black, crystal structure with ATP; gray and white, in solution with and without ATP, respectively. The asterisks indicate residues involved in ATP binding.

A well defined ATP-binding site for the ε subunit was found in this structure. The ATP in TF1ε takes on an unusual structure, in which the triphosphate chain bends at the β-phosphate. Because the structure fits well to the omit-difference map (Fig. 1), the average B factor for ATP is the smallest, and R and Rfree without ATP are larger than those with ATP (Table 1), this ATP structure is reliable. The ATP binding site is composed of β10, a loop and two helices. The residues involved in ATP binding are shown in Fig. 1B. A search with program PROSITE (35) failed to find a close homologue to this structure in the database of ATP binding motifs. This binding site is an ATP-specific one involving at least four residues. The carbonyl and amide groups of Asp-89 specifically recognize the adenine ring through Watson–Crick type hydrogen bonds. The π electron system of the guanidyl group of Arg-92 stacks on the adenine ring. Arg-92 also recognizes the ribose and γ-phosphate through hydrogen bonds. Therefore, these two residues play key roles in specific recognition of ATP. Actually, these two residues are conserved in most bacterial ε subunits (14). Furthermore, it turned out, as judged on inspection of the sequences, that Ile-88 and Ala-93 are also conserved in the same bacterial ε subunits, provided that Ile can be replaced by Leu. In the crystal structure, they actually contribute to form the adenine-binding pocket. Thus, we propose I(L)DXXRA (X, any amino acid residue) as a previously undescribed ATP-binding motif. In addition to these residues, the side chains of three Arg residues (Arg-99, Arg-122, and Arg-126) coordinate the phosphate group of ATP, and Glu-83 is also involved in formation of the adenine-binding pocket (Fig. 1B and SI Fig. 7). Because positive charges are concentrated around the ATP-binding site, the surface charge distribution is significantly different from that for EF1ε (SI Fig. 8).

The Backbone Assignment of NMR Signals and Secondary Structure Prediction of TF1ε in Solution.

Fig. 2 A and B presents 2D 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra of uniformly 15N labeled TF1ε in the presence and absence of ATP, respectively. The congested regions are expanded in SI Fig. 9. These spectra are significantly different from each other, revealing a structural change induced on ATP binding. Kd of the TF1ε/ATP complex is 1.4 μM at 36°C (32). The chemical shifts of backbone resonances were assigned by means of multidimensional and multinuclear NMR experiments. In the presence of ATP, the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum was well resolved. All NH resonances except for those of Pro and the N-terminal two residues were assigned. In the absence of ATP, on the other hand, the peaks appeared in a narrower chemical shift range. Nevertheless, the NH resonances could be completely assigned except for Pro, the C-terminal six and the N-terminal two residues, which were not observed. There were also some resonances exhibiting weak intensity, suggesting the coexistence of a minor conformation.

The Cα, Cβ, Hα, and HN chemical shifts of the assigned residues were analyzed with TALOS (36) to estimate dihedral angles φ and ψ in the presence and absence of ATP, respectively. The obtained angles are presented in SI Fig. 10 along with chemical shift deviations from the random coil (CSD). The secondary structures predicted on the basis of TALOS angles and CSD analysis (37) are shown in Fig. 2C. The secondary structure elements in the presence of ATP are almost the same for the crystal and solution structures. In contrast, those in the absence of ATP are different from those in the presence of ATP in the regions of β4∼β5 and the C-terminal domain. There are four helical regions with short linkers. On the basis of φ/ψ angles, however, three of them form a long single helix as shown by dotted lines in Fig. 2C, suggesting that the hairpin can turn into an extended helical structure on release of ATP.

Structure Determination of the C-Terminal Domain of TF1ε.

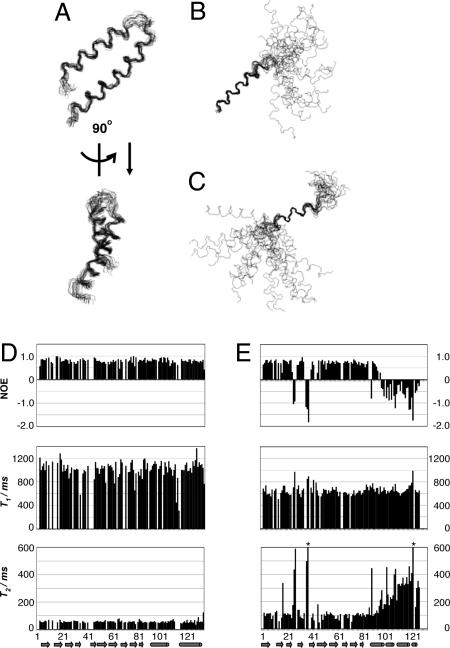

We determined the solution structure of CTD, because NTD and CTD are structurally independent. Indeed, the solution structure of EF1ε was obtained through individual determination of the two domains (15). CTD of TF1ε can be defined as residues 90–133 based on the crystal structure. We have determined the solution structures of residues 88–133 and 88–127 of the whole protein in the presence and absence of ATP, respectively. They were calculated with CYANA, by using 397 and 311 distance restraints, and 89 and 77 dihedral angle restraints, respectively (SI Table 2). Of the 100 structures calculated, the best 20 were superimposed in Fig. 3. In the presence of ATP (Fig. 3A), the conformation of the CTD backbone of TF1ε was well defined except for the N and C-terminal residues, and the backbone rmsd of the 20 structures (residues 90–131) was 0.50 Å. This structure comprises two antiparallrel helices (α1; residues 90–105 and α2; 113–131) connected by a loop. Twenty-six inter-helix NOEs were observed. The hairpin structure was identical for the crystal and solution structures, revealing that the crystal structure holds also in solution. The ATP binding was evidenced by the Asp-89 NH signal, which was observed at 11 ppm in the presence of ATP. The unusual down-field shift can be ascribed to hydrogen bonding with the adenine of ATP. In contrast, the best 20 structures in the absence of ATP did not converge, and the backbone rmsd was >4 Å. The structure was basically helical with two well defined helices (residues 90–102 and 113–117). The former includes one of dotted regions in Fig. 2C, suggesting that the short linkers can actually take helical structures in solution. Inter-helix NOEs were not observed. When each helical region was superimposed, they were well defined with backbone rmsd of 0.39 Å and 0.28 Å, respectively (Fig. 3 B and C). It should be emphasized that even the flexible region showed a helical feature on secondary structure analysis (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 3.

Solution structures of the C-terminal domain of TF1ε and their relaxation prameters. (A) Superposition of 20 structures with the lowest target function values in the presence of ATP for residues 90–131. (B and C) Those in the absence of ATP. The backbone heavy atoms are superimposed for the regions comprising residues 90–102 (B) and residues 113–117 (C). (D and E) 15N NOE, T1, and T2 of TF1ε amide signals in the presence (D) and absence (E) of ATP as a function of sequence number. T2 values with asterisks at 38 and 122 are 614 and 732 ms, respectively.

Dynamic Properties of TF1ε in Solution.

Relaxation parameters of TF1ε were obtained for in the presence and absence of ATP in solution. They are summarized in Fig. 3 D and E as a function of sequence number. The ATP-bound TF1ε reveals uniform NOE, T1 and T2 values all through the sequence, showing that NTD and CTD form a rigid body through strong interdomain interactions mediated by ATP. On the other hand, two domains exhibit completely different dynamic properties in the absence of ATP. NTD up to β10 forms a rigid body and CTD becomes more and more flexible with approaching to the C terminus. Its dynamics also well corresponds to the secondary structure elements shown in Fig. 2C and is consistent with the solution structure of CTD. In contrast to the ATP-bound form, loops linking secondary structure elements are flexible. This property makes whole molecule more flexible as can be seen in smaller NOE, shorter T1 and longer T2 than those for the ATP-bound form. This result indicates that the interaction between NTD and CTD is important to keep each domain rigid.

Does EF1ε Bind ATP?

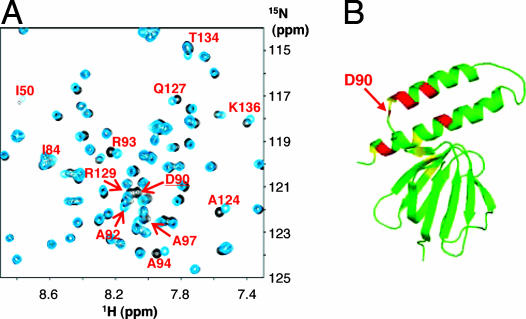

We have also examined ATP binding to the isolated EF1ε. The 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of uniformly 15N labeled EF1ε was almost the same as that reported previously (38) (Fig. 4A and SI Fig. 11A). Because the assignment was made in the previous study (38), an ATP titration experiment was carried out. The NH resonance of Asp-90 disappeared at the molar ratio of ATP/ε = 1. This residue corresponds to Asp-89 of TF1ε, whose amide nitrogen directly binds to the adenine ring of ATP. This signal appeared again with a down-field shift at ATP/ε = 3. This sample was titrated with ATP up to ATP/ε = 50. The dissociation constant (Kd) obtained from the titration curve is 22 ± 1 mM at 25°C (SI Fig. 11B). Several other signals were also perturbed along with that of Asp-90. The average chemical shift perturbation (Δδave) of each NH resonance in the presence of ATP was calculated by using the equation, Δδave = [ΔδH2+(ΔδN/5)2]1/2, where ΔδH and ΔδN are the differences in the 1H and 15N chemical shifts, respectively (SI Fig. 11C). The perturbed residues (Δδave > 0.03) were Asp-90, Arg-93, Ala-94, Ala-97, Ala-124, and Thr-134 at ATP/ε = 7, and Ile-50, Tyr-63, Ile-84, Ala-92, Arg-129, and Lys-136 in addition to the previous ones at ATP/ε = 10. These residues were mapped on the solution structure of EF1ε (15) (Fig. 4B). They are located in the area same as the ATP-binding site in TF1ε (Fig. 1B). Especially Asp-90, Arg-93, and Ala-94 are the key residues in the ATP-binding motif. Therefore, it can be concluded that EF1ε has an ATP-binding site at the same position as in TF1ε although the affinity is very low.

Fig. 4.

The chemical shift perturbations induced by ATP for the signals of EF1 ε subunit. (A) A relevant region of 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the uniformly 15N labeled EF1ε in the absence of ATP (black) and in the presence of 10-fold ATP (blue). The whole spectra are given in SI Fig. 11A. (B) Mapping of the residues on the solution structure of EF1ε perturbed by the ATP titration. Red and yellow indicate the perturbed residues in the case of 7- and 10-fold ATP, respectively.

Discussion

Our structural analysis has clearly shown that TF1ε takes on two conformations in CTD, folded and extended ones, depending on ATP-binding. On the basis of TALOS analysis and structure determination, ATP-free CTD takes on a long helical structure with high flexibility in the C-terminal half. This result provides a structural basis for elucidation of the regulation of ATPase activity by the ε subunit in F1. Cross-linking and FRET experiments indicated that the C terminus of ε and the N terminus of the γ subunit could come close to each other in TF1 in the absence of ATP, suggesting that its CTD takes on a structure extending along the axial helices of the γ subunit (the up-extended form) (31, 32). It was also shown that the structure could reversibly change between the up-extended (up-state) and folded (down-state) forms, depending on the ATP concentration (32). The extended long helical structure of the isolated TF1ε is consistent with the up-extended conformation of F1. The reversible binding of ATP to the isolated TF1ε and the resulting conformational change from the extended to folded forms must be the basis for the reversible conversion between the up and down states.

A model structure for the up-extended form of F1ε is presented in Fig. 5 on the basis of our results, the observations mentioned above and the crystal structure of MF1 (16). In the case of EF1, the bottom part of the γ subunit is unwound by ≈80° in comparison with that in MF1 (39). This observation suggests that the γ subunit can fluctuate under certain conditions. Because ε NTD binds to the γ axial helices at the bottom for both structures, the ε CTD helix can extend up along either γ helix. The fluctuation of γ and the flexibility of ε would facilitate the reversible conversion between the up-extended and down-folded structures. This structural conversion can be regarded as an arm-like motion of ε CTD. As shown by the γ′ε crystal structure and FRET, there could be intermediate forms between the up-extended and down-folded conformations. This kind of equilibrium can explain the inconsistent results of cross-linking experiments so far reported, namely, βD380C-εS108C, βE381C-εS108C, βS383C-εS108C, εA117C-cc′Q42C, and γL99C-εS118C for E. coli (23, 26, 40), and γS3C-εC134 and εA85C-εC134 for PS3 (31). ATP hydrolysis starts with binding of ATP to an empty catalytic site with a conformational change from the open to closed form (1–7). Usually, this conformational change induces clockwise rotation of γ in Fig. 5 (on the top and right). However, the presence of the ε helix would block this rotation, because the contact between the closed form of β and the γ axle is tight even without ε, leaving little space for the γε axle to get through. This blockage results in inhibition of ATPase activity. On the other hand, anticlockwise rotation for ATP synthesis would be possible because βTP will change to βE, leading to looser contact with the axle. The flexible property of the ε helix will help get it through the relatively narrow space.

TF1ε specifically binds ATP and forms a folded conformation in solution as well as in the crystal. The ATP-binding to TF1ε is very unique. In the ATP-binding motif of bacterial ε subunits, I(L)DXXRA, the adenine ring is recognized by the backbone rather than the side chain of Asp-89, which is not directly involved in the interaction with ATP. Nevertheless, Asp is completely conserved in the motif. The side chain seems to help ATP fit into the correct orientation with the electrostatic repulsion against triphosphate groups. It also contributes to formation of the adenine pocket. In addition to the general motif, Glu-83 and Arg-99 play unique roles. At the position of Arg-99, positively charged residues (Arg or Lys) are highly conserved in bacteria. The side chain of Arg-99 interacts with the γ-phosphate, suggesting that this residue contributes to the recognition of triphosphate group. The position of Glu-83 is occupied by either Glu or Ile in the bacteria that have the ATP-binding motif. Both have long side chains, which could participate in the formation of the adenine pocket. In particular, Glu can stabilize the ribose through hydrogen bonding (Fig. 1B and SI Fig. 7). Therefore, a higher ATP binding affinity would be expected for the ε subunits that have Glu and Arg at the positions mentioned above, respectively, in addition to the ATP binding motif. Actually, the ε subunits of PS3 and B. subtilis have Glu and Arg whereas EF1ε has Ile and Lys at these positions. Glu-83 also stabilizes the orientation of CTD relative to NTD through the hydrogen bonding.

There is no ATP-binding motif in chloroplast ε subunits (14). Therefore, it is expected to take on only the extended conformation in F1. In the case of chloroplasts, FoF1 ATP synthase should be used solely for ATP synthesis. Thus, the extended conformation inhibits ATP hydrolysis and keeps ATP synthesis going. In the case of bacteria, however, their environment can change drastically. Although FoF1 ATP synthase is also mainly used for ATP synthesis in bacteria under normal conditions, it has to pump out protons in an acidic environment such as in acidic hot springs. To cope with this situation, the inhibitory action would be suppressed through conversion of CTD from the up-extended to the down-folded conformation. Because acidic conditions can cause the production of much ATP, The ATP concentration could be one of the major regulation factors, as shown by cross-linking and FRET experiments on TF1 (35). Actually, Kd of the TF1ε/ATP complex is 0.67 mM at physiological temperature (65°C), in contrast to 1.4 μM at 36°C (32). Thus, the ATP-free form should be the major species of TF1ε under normal physiological conditions. This value should be compared with Kd = 22 mM for E. coli.

In conclusion, we have found a significant structural change from an extended to the folded conformation depending on ATP-binding in TF1ε. The latter has a well-defined ATP-binding site with a sequence motif, I(L)DXXRA, that is conserved in most bacterial ε subunits. The ATP binding to EF1ε (this work) and to B. subtilis ε (34) support the proposed motif. An up-extended structural model was proposed based on the obtained conformations and the information reported so far. This model can provide the mechanism for the inhibition of ATPase activity coupled with the arm motion of TF1ε CTD regulated by ATP. It has been reported that it took 9–12 months for the crystallization of EF1ε (14). This fact suggests that there is also an equilibrium between the folded and unfolded forms of EF1ε CTD in the absence of ATP. However, determination of the role of ATP binding in EF1ε remains for future research.

Materials and Methods

Protein Preparation.

The genes of TF1 and EF1ε subunits harbored in pET21c were expressed in E. coli strain BL21 (DE3), and selenomethionyl protein was produced in E. coli strain BL21 codon plus (DE3)-RIL/pET21c. All proteins were purified as described (33) with an additional gel-filtration. Uniformly, 15N-, and 13C-,15N-labeled TF1 and EF1 ε subunits were produced by using 15NH4Cl, and U-13C-glucose and 15NH4Cl in M9 medium, respectively (see SI Materials and Methods).

Crystallization and Structure Determination.

Crystallization was carried out at 20°C by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. The concentrations of purified proteins were adjusted to 20 mg/ml (1.4 mM) in 50 mM potassium phosphate (KPi) buffer, pH 6.8, including 10 mM NaCl and 1.5 mM ATP. Crystals of proteins were obtained from a reservoir solution containing 100 mM citric acid buffer, pH 4.0, including 5% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 6000. The crystals belong to orthorhombic space group P212121, and the unit cell dimensions are a = 37.5 Å, b = 64.9 Å, c = 103.9 Å, α = β = γ = 90°.

X-ray diffraction data of native crystals were collected by using an imaging plate detector DIP-6040 (MAC Science/Bruker AXS, Yokohama, Japan) at beam line BL44XU of SPring-8. X-rays were monochromatized with a Si (1 1 1) monochrometer, and focused with a mirror. The wave-length of x-ray was tuned at 0.90 Å, and collimated to a size of 50 μm × 50 μm. All data sets were collected at 100 K. The data collection statistics are summarized in SI Table 3. An initial phase obtained by the multiwavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) method was improved by solvent flattening and histogram matching with program DM (41). The modified electron density map revealed the main chain and most of the side chains. Because TF1ε was a homodimer, one molecule was built into the electron density map by using program O (42), and the other one was generated by the NCS operation. Because the C-terminal loop was not clear, 2Fo-Fc omit maps were used to built structural models of this region. Simulated annealing and positional, and B-factor refinement were carried out with program CNS (43) (see SI Materials and Methods).

NMR Measurements and Structure Determination.

NMR spectra were obtained with Bruker DRX500 and DRX600 NMR spectrometers at 30°C (TF1) and 25°C (EF1). TF1ε subunits were dissolved at 0.5–1 mM in 50 mM KPi buffer, pH 6.8, containing 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaN3 and 10% 2H2O. Two-dimensional (2D) 1H-15N HSQC spectra were obtained with a data size of 256 (15N) × 2048 (1H) complex points. Sequential assignments of the backbone resonances of the TF1ε were performed by using HNCACB, HN(CO)CACB, HNCO, HN(CO)CA and HBHA(CO)NH spectra. Side chain signals were assigned only for the C-terminal domain of the full-length TF1ε by using H(CCO)NH and C(CO)NH spectra. The EF1ε subunit was dissolved at 0.5 mM in 50 mM KPi buffer, pH 7.4, containing 10% 2H2O. For ATP titration, a small amount of a 250 mM ATP solution was added directly to the sample solution. All NMR data were processed with NMRPipe and NMRDraw (44), and analyzed with Sparky, a program developed by T. D. Goddard and D. G. Kneller of the University of California (San Francisco, CA).

Distance and backbone torsion angle restraints were acquired by 2D NOESY, 15N-edited NOESY and 13C-edited NOESY spectra (mixing time, 100 ms), and TALOS analysis (36). The restraints for the backbone dihedral angles, φ and ψ, were applied in the forms of average ± 2 SD (standard deviation) and 3 SD for Good and New categories, respectively. The structures were calculated with software CYANA 1.0.6 (45) by means of molecular dynamics in a torsion angle space, with 40,000 steps. The best 20 of 100 calculated structures were analyzed with MOLMOL (46) and PROCHECK-NMR software (47). Spectra for determining 15N longitudinal relaxation times, T1, 15N transverse relaxation times, T2, and {1H}-15N steady-state heteronuclear NOE were acquired at 30°C with a DRX600 spectrometer. The pulse sequences included the combination of sensitivity enhancement and gradient echo for the indirect 15N dimensions (48) (see SI Materials and Methods).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (to H.A.) and Grants-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (to H.Y.) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Technology, Sport and Culture of Japan, and grants from Japan Science and Technology Agency (CREST) (to H.A.) and ERATO (to M.Y.).

Abbreviations

- NTD

N-terminal domain of ε subunit

- CTD

C-terminal domain of ε subunit, respectively.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2E5Y for the crystal structure of TF1 ε; PDB ID code 2E5U and 2E5T for the solution structure of CTD of TF1 ε in the absence and in the presence of ATP, respectively).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0701045104/DC1.

References

- 1.Boyer PD. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:717–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stock D, Gibbons C, Arechaga I, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:672–679. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshida M, Muneyuki E, Hisabori T. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:669–677. doi: 10.1038/35089509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capaldi RA, Aggeler R. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:154–160. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)02051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber J, Senior AE. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1319:19–58. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(96)00121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrahams JP, Leslie AGW, Lutter R, Walker JE. Nature. 1994;370:621–628. doi: 10.1038/370621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyer PD. FEBS Lett. 2002;512:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duncan TM, Bulygin VV, Zhou Y, Hutcheon ML, Cross RL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10964–10968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aggeler R, Ogilvie I, Capaldi RA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19621–19624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noji H, Yasuda R, Yoshida M, Kinoshita K., Jr Nature. 1997;386:299–302. doi: 10.1038/386299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laget PP, Smith JB. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1979;197:83–89. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sternweis PC, Smith JB. Biochemistry. 1980;19:526–531. doi: 10.1021/bi00544a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato-Yamada Y, Bald D, Koike M, Motohashi K, Hisabori T, Yoshida M. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33991–33994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uhlin U, Cox GB, Guss JM. Structure (London) 1997;5:1219–1230. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkens S, Dahlquist FW, Mclntosh LP, Donaldson LW, Capaldi RA. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:961–967. doi: 10.1038/nsb1195-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbons C, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1055–1061. doi: 10.1038/80981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiong H, Zhang D, Vik SB. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16423–16429. doi: 10.1021/bi981522i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuki M, Noumi T, Maeda M, Amemura A, Futai M. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17437–17442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nowak KF, Tabidze V, McCarty RE. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15130–15134. doi: 10.1021/bi026594v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nowak KF, McCarty RE. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3273–3279. doi: 10.1021/bi035820d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cipriano DJ, Dunn SD. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:501–507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509986200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dallmann HG, Flynn TG, Dunn SD. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18953–18960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aggeler R, Haughton MA, Capaldi RA. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9185–9191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang C, Capaldi RA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3018–3024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aggeler R, Capaldi RA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13888–13891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bulygin VV, Duncan TM, Cross TL. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31765–31769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsunoda SP, Rodgers AJW, Aggeler R, Wilce MCJ, Yoshida M, Capaldi RA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6560–6564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111128098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulenburg B, Capaldi RA. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28351–28355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato-Yamada Y, Yoshida M, Hisabori T. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35746–35750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006575200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodgers AJW, Wilce MCJ. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1051–1054. doi: 10.1038/80975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki T, Murakami T, Iino R, Suzuki J, Ono S, Shirakihara Y, Yoshida M. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46840–46846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iino R, Murakami T, Iizuka S, Kato-Yamada Y, Suzuki T, Yoshida M. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40130–40134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato-Yamada Y, Yoshida M. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36013–36016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kato-Yamada Y. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:6875–6878. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bucher P, Bairoch A. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1994;2:53–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. J Bionol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wishart DS, Bigam CG, Holm A, Hodges RS, Sykes BD. J Biomol NMR. 1995;5:67–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00227471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilkens S, Capaldi RA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26645–26651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hausrath AC, Capaldi RA, Matthews BW. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47227–47232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bulygin VV, Duncan TM, Cross TL. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35616–35621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cowtan K, Main P. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:487–493. doi: 10.1107/s0907444997011980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones TA, Zou J-Y, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, Delano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang J-S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Güntert P, Mumenthaler C, Wüthrich K. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:283–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laskowski RA, Rullmann JAC, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. J Mol Biol. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farrow NA, Muhandiram R, Singer AU, Pascal SM, Kay CM, Gish G, Shoelson SE, Pawson T, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5984–6003. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.