Abstract

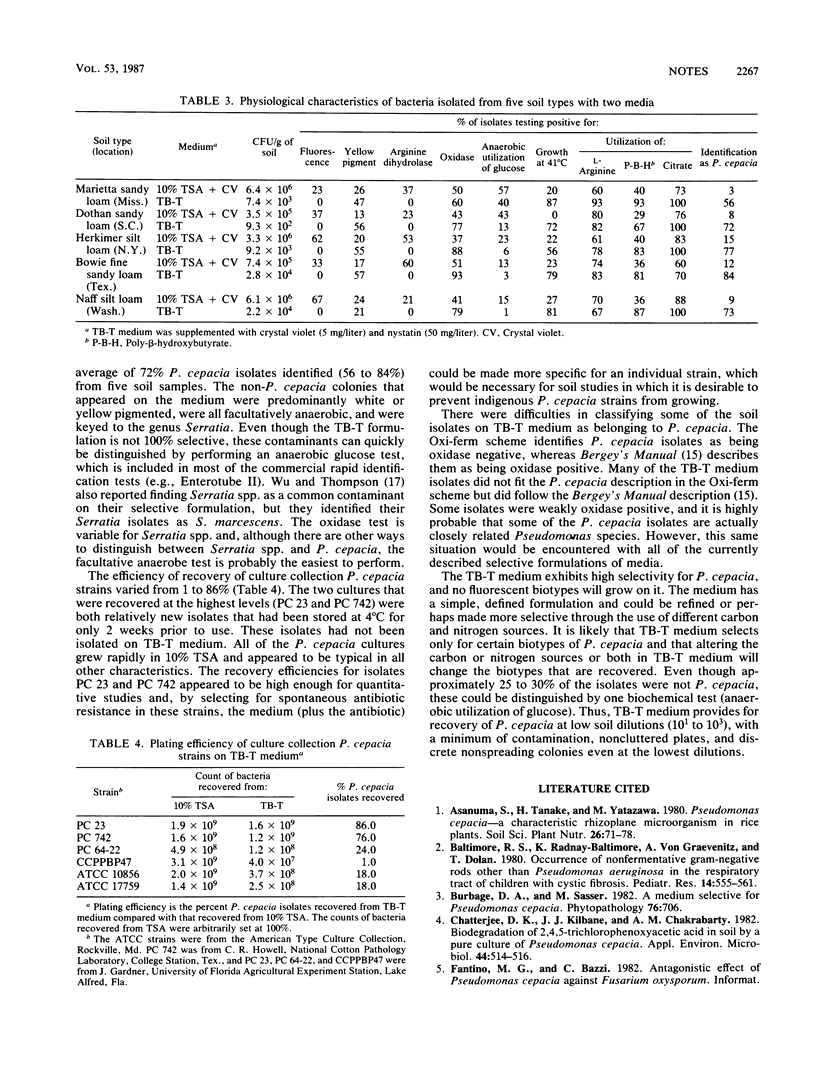

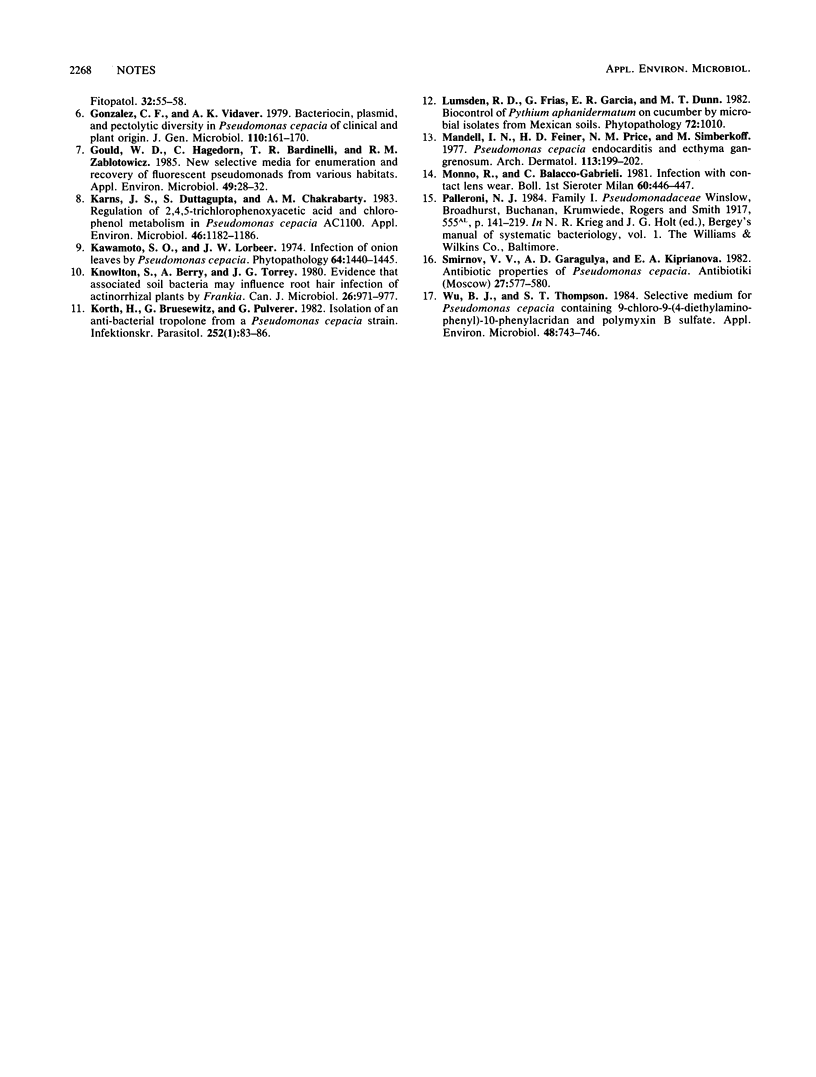

TB-T medium provides a high degree of selectivity for and detection of Pseudomonas cepacia biotypes upon initial plating from soil. TB-T medium consists of a basal medium with glucose as the sole carbon source and asparagine as the sole nitrogen source. The selectivity of TB-T medium is based on the combination of trypan blue (TB) and tetracycline (T) (pH 5.5). On TB-T medium, 216 of 300 isolates (72%) from five different soil types were identified as P. cepacia. The remaining 28% were facultative organisms that could be separated readily from P. cepacia by anaerobic glucose fermentation and by their inability to grow at 41 degrees C. Molds were controlled on low soil dilutions by adding crystal violet, nystatin, or both. Elimination of either ingredient or elevation of the pH to 7.5 resulted in a pronounced loss of selectivity. The efficiency of recovery varied considerably among P. cepacia strains but was high enough for some strains (76 to 86%) to permit quantitative studies. TB-T medium combines a defined formulation with high selectivity and allows recovery of P. cepacia biotypes from low soil dilutions (10(1) to 10(3)).

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chatterjee D. K., Kilbane J. J., Chakrabarty A. M. Biodegradation of 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid in soil by a pure culture of Pseudomonas cepacia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982 Aug;44(2):514–516. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.2.514-516.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C. F., Vidaver A. K. Bacteriocin, plasmid and pectolytic diversity in Pseudomonas cepacia of clinical and plant origin. J Gen Microbiol. 1979 Jan;110(1):161–170. doi: 10.1099/00221287-110-1-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould W. D., Hagedorn C., Bardinelli T. R., Zablotowicz R. M. New selective media for enumeration and recovery of fluorescent pseudomonads from various habitats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985 Jan;49(1):28–32. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.1.28-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karns J. S., Duttagupta S., Chakrabarty A. M. Regulation of 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid and chlorophenol metabolism in Pseudomonas cepacia AC1100. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983 Nov;46(5):1182–1186. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.5.1182-1186.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton S., Berry A., Torrey J. G. Evidence that associated soil bacteria may influence root hair infection of actinorhizal plants by Frankia. Can J Microbiol. 1980 Aug;26(8):971–977. doi: 10.1139/m80-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korth H., Brüsewitz G., Pulverer G. Isolierung eines antibiotisch wirkenden Tropolons aus einem Stamm von Pseudomonas cepacia. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A. 1982 May;252(1):83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell I. N., Feiner H. D., Price N. M., Simberkoff M. Pseudomonas cepacia endocarditis and ecthyma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 1977 Feb;113(2):199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monno R., Balacco-Gabrieli C. Infection with contact lens wear. Boll Ist Sieroter Milan. 1981 Nov;60(5):446–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B. J., Thompson S. T. Selective medium for Pseudomonas cepacia containing 9-chloro-9-(4-diethylaminophenyl)-10-phenylacridan and polymyxin B sulfate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984 Oct;48(4):743–746. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.4.743-746.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]