Abstract

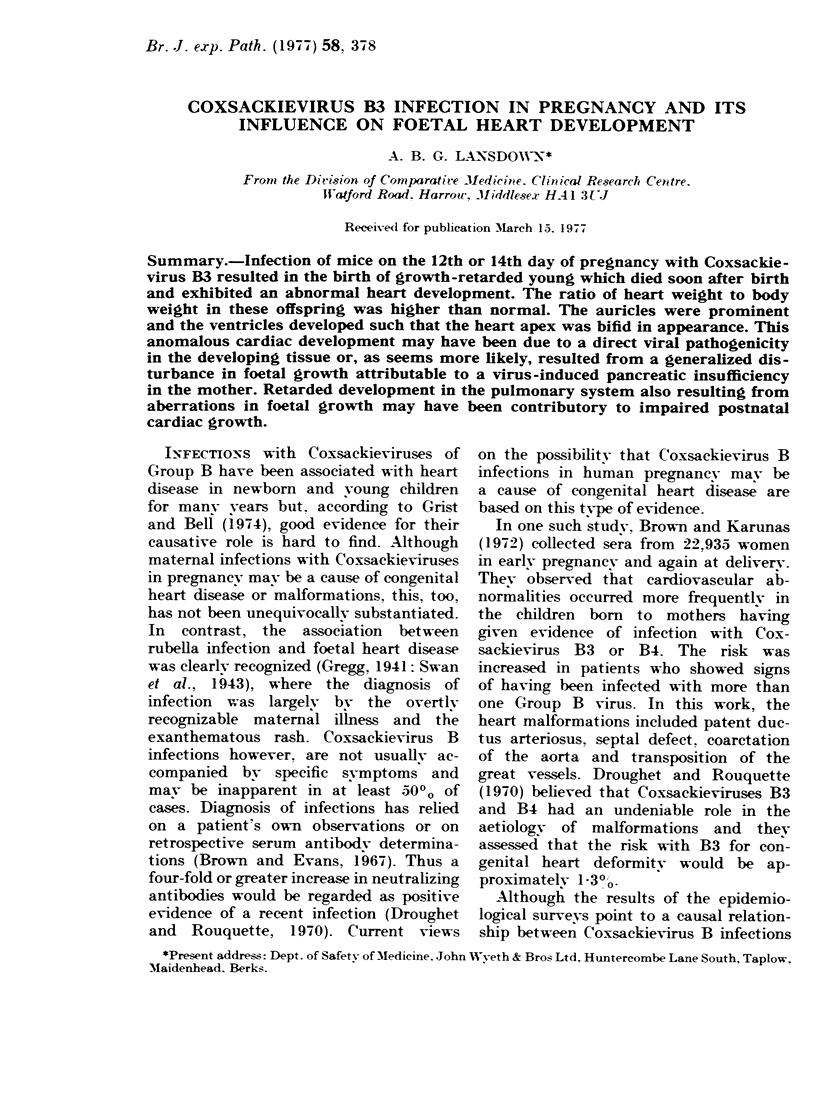

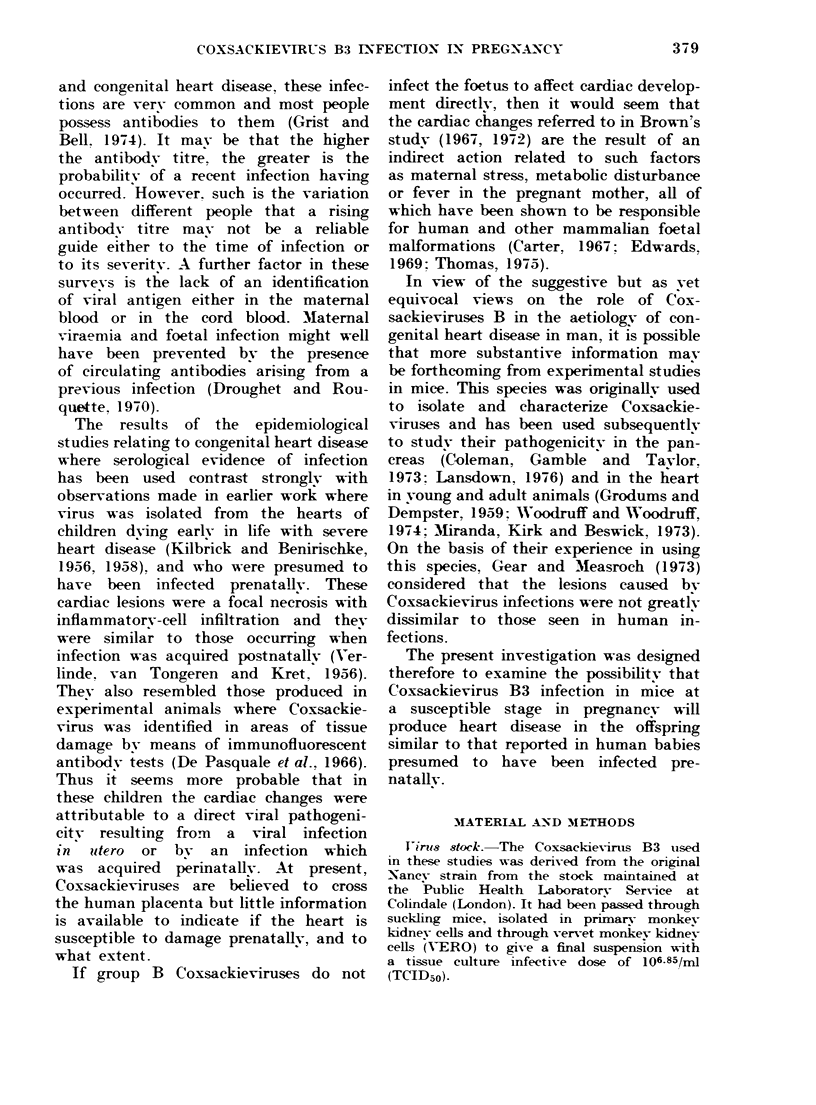

Infection of mice on the 12th or 14th day of pregnancy with Coxsackievirus B3 resulted in the birth of growth-retarded young which died soon after birth and exhibited an abnormal heart development. The ratio of heart weight to body weight in these offspring was higher than normal. The auricles were prominent and the ventricles developed such that the heart apex was bifid in appearance. This anomalous cardiac development may have been due to a direct viral pathogenicity in the developing tissue or, as seems more likely, resulted from a generalized disturbance in foetal growth attributable to a virus-induced pancreatic insufficiency in the mother. Retarded development in the pulmonary system also resulting from aberrations in foetal growth may have been contributory to impaired postnatal cardiac growth.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brown G. C., Evans T. N. Serologic evidence of Coxsackievirus etiology of congenital heart disease. JAMA. 1967 Jan 16;199(3):183–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. C., Karunas R. S. Relationship of congenital anomalies and maternal infection with selected enteroviruses. Am J Epidemiol. 1972 Mar;95(3):207–217. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter C. O. Congenital malformations. WHO Chron. 1967 Jul;21(7):287–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coid C. R., Ramsden D. B. Retardation of foetal growth and plasma protein development in foetuses from mice injected with Coxsackie B3 virus. Nature. 1973 Feb 16;241(5390):460–461. doi: 10.1038/241460a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePasquale N. P., Burch G. E., Sun S. C., Hale A. R., Mogabgab W. J. Experimental Coxsackie virus B4 valvulitis in cynomolgus monkeys. Am Heart J. 1966 May;71(5):678–683. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(66)90319-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M. J. Congenital defects in guinea pigs: prenatal retardation of brain growth of guinea pigs following hyperthermia during gestation. Teratology. 1969 Nov;2(4):329–336. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420020407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRODUMS E. I., DEMPSTER G. Myocarditis in experimental Coxsackie B-3 infection. Can J Microbiol. 1959 Dec;5:605–615. doi: 10.1139/m59-074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grist N. R., Bell E. J. A six-year study of coxsackievirus B infections in heart disease. J Hyg (Lond) 1974 Oct;73(2):165–172. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400023998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdown A. B. Pathological changes in the pancreas of mice following infection with Coxsackie B viruses. Br J Exp Pathol. 1976 Jun;57(3):331–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda Q. R., Kirk R. S., Beswick T. S. The long-term effects of neonatal Coxsackie-B5 infection in mice: reduced fecundity of recovered females. J Pathol. 1973 Mar;109(3):183–193. doi: 10.1002/path.1711090303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soike K. Coxsackie B-3 virus infection in the pregnant mouse. J Infect Dis. 1967 Jun;117(3):203–208. doi: 10.1093/infdis/117.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff J. F., Woodruff J. J. Involvement of T lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of coxsackie virus B3 heart disease. J Immunol. 1974 Dec;113(6):1726–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]