Abstract

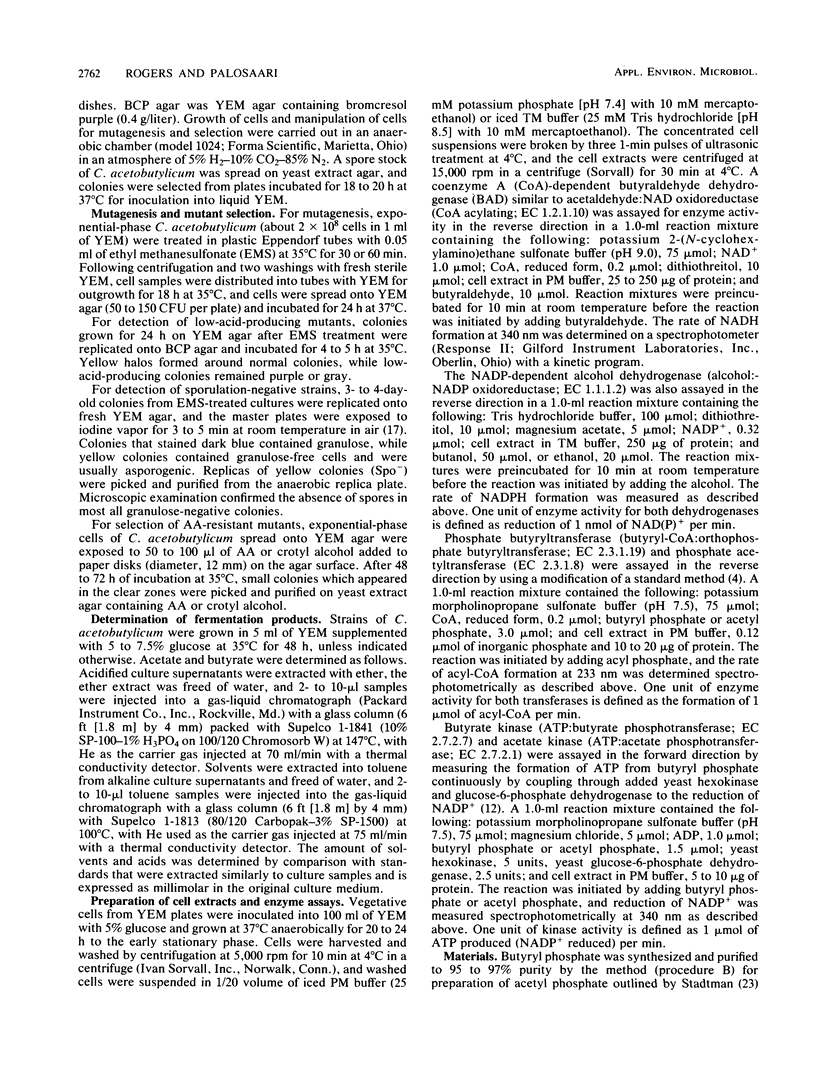

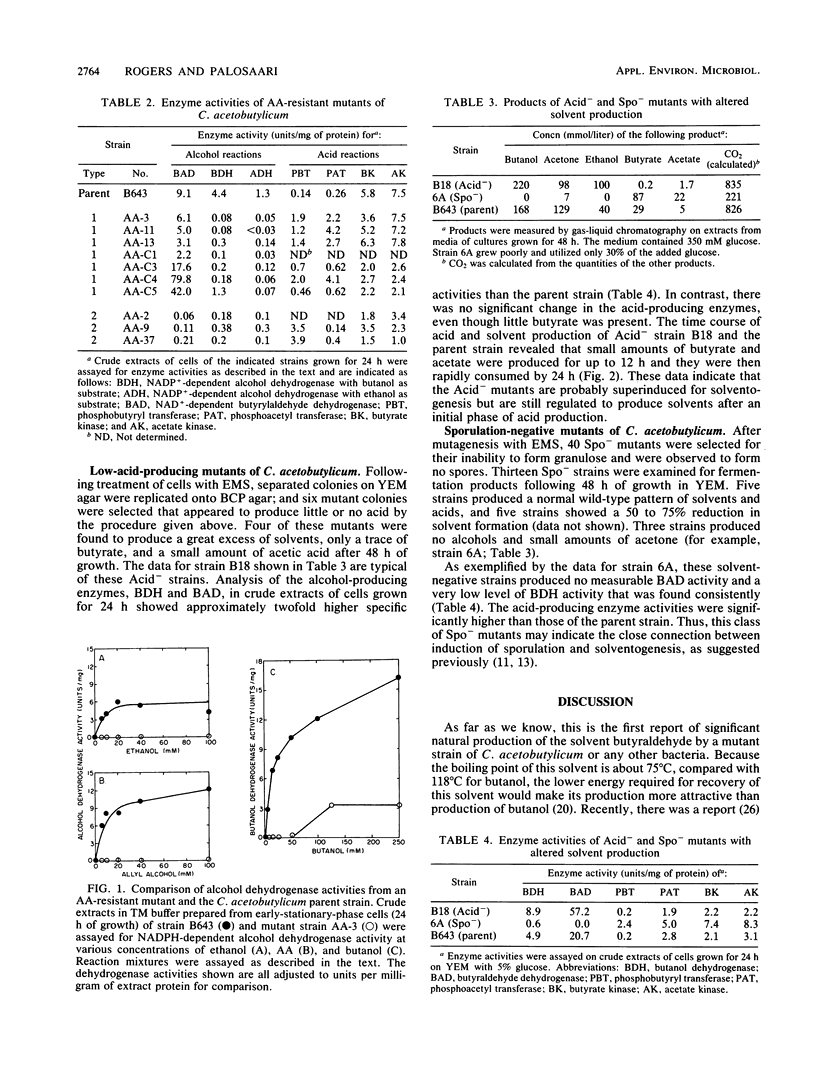

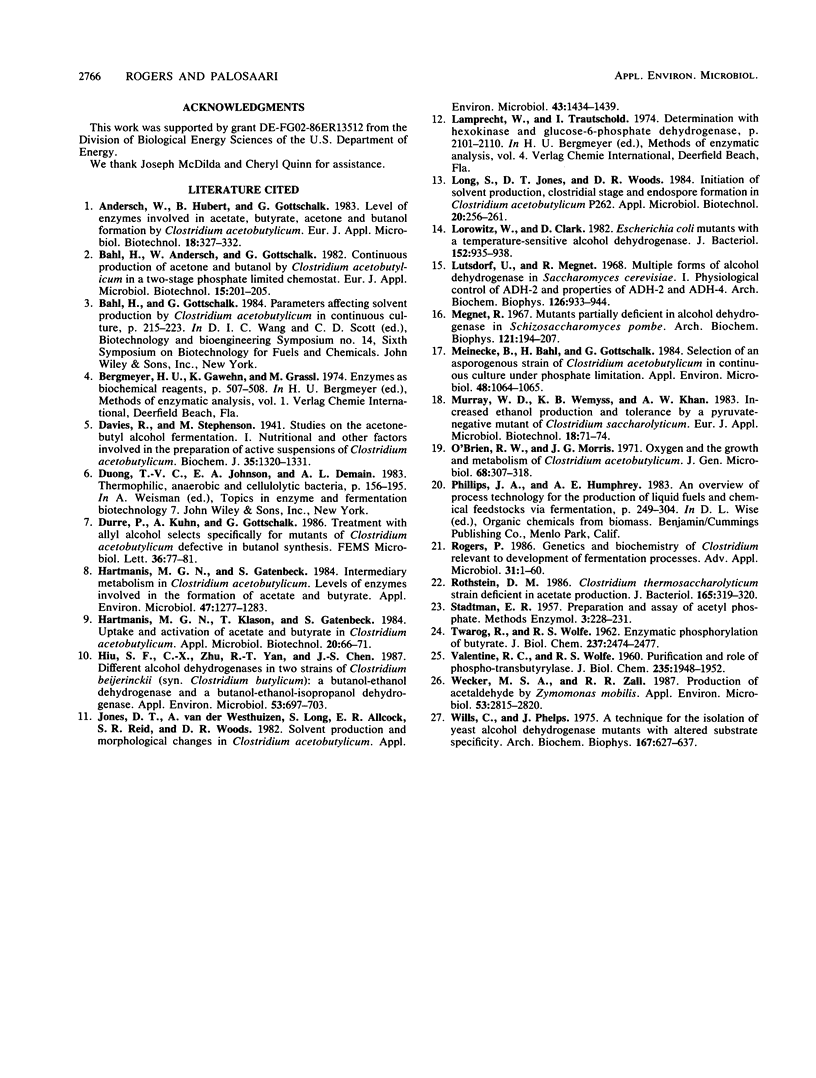

Spontaneous mutants of Clostridium acetobutylicum NRRL B643 that were resistant to allyl alcohol (AA) were selected and characterized. These mutants contained 10- to 100-fold reduced activities of butanol and ethanol alcohol dehydrogenase. The AA mutants formed two groups and produced no ethanol. Type 1 AA mutants produced significant amounts of a new solvent, butyraldehyde, and contained normal levels of the coenzyme A-dependent butyraldehyde dehydrogenase (BAD). Type 2 AA mutants produced no significant butyraldehyde and lower levels of all solvents, and they contained 45- to 100-fold lower activity levels of BAD. Following ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenesis, low-acid-producing (Acid−) mutants were selected and characterized as superinduced solvent producers, yielding more than 99% of theoretical glucose carbon as solvents and only small amounts of acetate and butyrate. Following ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenesis, 13 sporulation-negative (Spo−) mutants were characterized; and 3 were found to produce only butyrate and acetate, a minor amount of acetone, and no alcohols. These Spo− mutants contained reduced butanol dehydrogenase activity and no BAD enzyme activity. The data support the view that the type 2 AA, the Acid−, and the Spo− mutants somehow alter normal regulated expression of the solvent pathway in C. acetobutylicum.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Davies R., Stephenson M. Studies on the acetone-butyl alcohol fermentation: Nutritional and other factors involved in the preparation of active suspensions of Cl. acetobutylicum (Weizmann). Biochem J. 1941 Dec;35(12):1320–1331. doi: 10.1042/bj0351320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmanis M. G., Gatenbeck S. Intermediary Metabolism in Clostridium acetobutylicum: Levels of Enzymes Involved in the Formation of Acetate and Butyrate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984 Jun;47(6):1277–1283. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.6.1277-1283.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiu S. F., Zhu C. X., Yan R. T., Chen J. S. Butanol-Ethanol Dehydrogenase and Butanol-Ethanol-Isopropanol Dehydrogenase: Different Alcohol Dehydrogenases in Two Strains of Clostridium beijerinckii (Clostridium butylicum). Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987 Apr;53(4):697–703. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.4.697-703.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. T., van der Westhuizen A., Long S., Allcock E. R., Reid S. J., Woods D. R. Solvent Production and Morphological Changes in Clostridium acetobutylicum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982 Jun;43(6):1434–1439. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.6.1434-1439.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorowitz W., Clark D. Escherichia coli mutants with a temperature-sensitive alcohol dehydrogenase. J Bacteriol. 1982 Nov;152(2):935–938. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.2.935-938.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutstorf U., Megnet R. Multiple forms of alcohol dehydrogenase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. I. Physiological control of ADH-2 and properties of ADH-2 and ADH-4. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968 Sep 10;126(3):933–944. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90487-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megnet R. Mutants partially deficient in alcohol dehydrogenase in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1967 Jul;121(1):194–201. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(67)90024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinecke B., Bahl H., Gottschalk G. Selection of an Asporogenous Strain of Clostridium acetobutylicum in Continuous Culture Under Phosphate Limitation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984 Nov;48(5):1064–1065. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.5.1064-1065.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien R. W., Morris J. G. Oxygen and the growth and metabolism of Clostridium acetobutylicum. J Gen Microbiol. 1971 Nov;68(3):307–318. doi: 10.1099/00221287-68-3-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein D. M. Clostridium thermosaccharolyticum strain deficient in acetate production. J Bacteriol. 1986 Jan;165(1):319–320. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.1.319-320.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TWAROG R., WOLFE R. S. Enzymatic phosphorylation of butyrate. J Biol Chem. 1962 Aug;237:2474–2477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALENTINE R. C., WOLFE R. S. Purification and role of phosphotransbutyrylase. J Biol Chem. 1960 Jul;235:1948–1952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wecker M. S., Zall R. R. Production of Acetaldehyde by Zymomonas mobilis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987 Dec;53(12):2815–2820. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.12.2815-2820.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills C., Phelps J. A technique for the isolation of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase mutants with altered substrate specificity. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1975 Apr;167(2):627–637. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(75)90506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]