Abstract

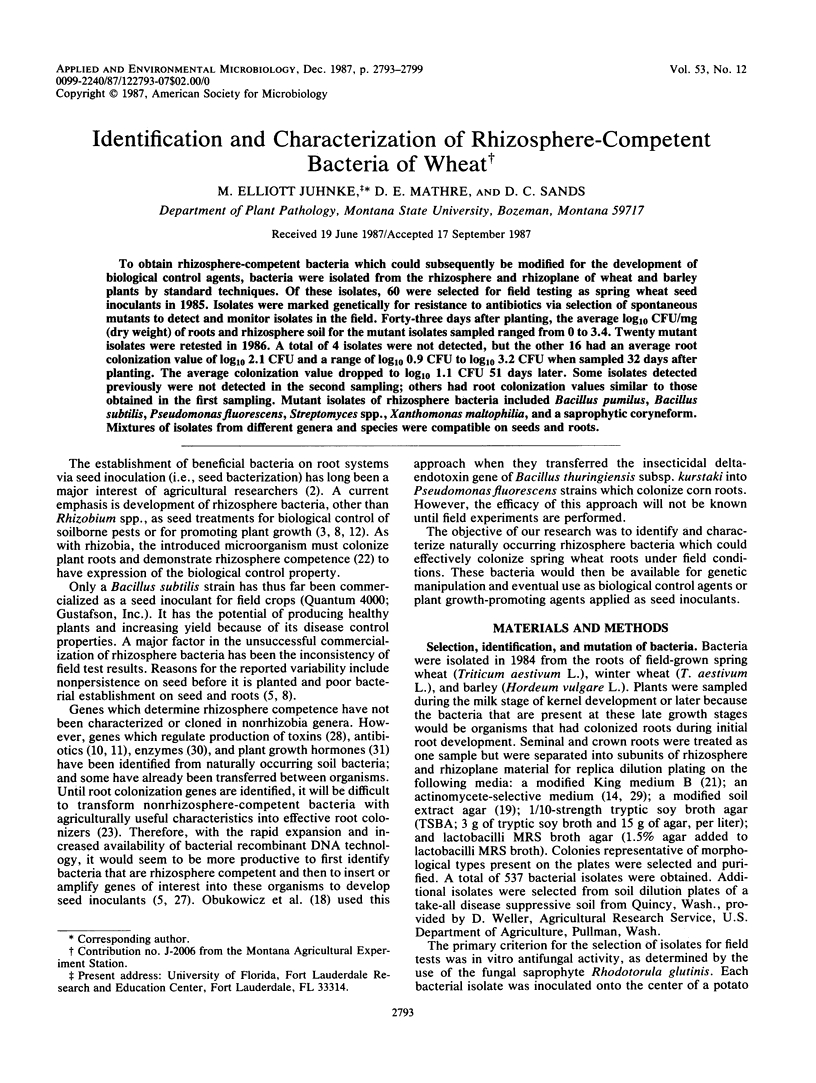

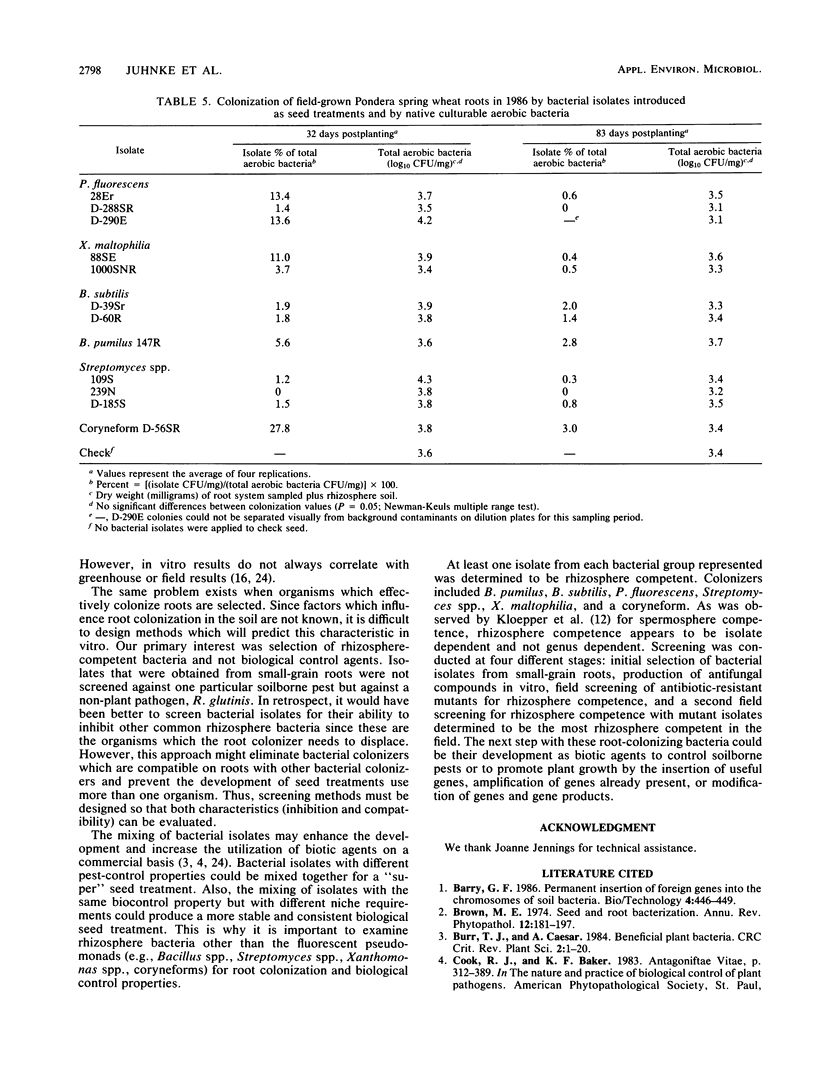

To obtain rhizosphere-competent bacteria which could subsequently be modified for the development of biological control agents, bacteria were isolated from the rhizosphere and rhizoplane of wheat and barley plants by standard techniques. Of these isolates, 60 were selected for field testing as spring wheat seed inoculants in 1985. Isolates were marked genetically for resistance to antibiotics via selection of spontaneous mutants to detect and monitor isolates in the field. Forty-three days after planting, the average log10 CFU/mg (dry weight) of roots and rhizosphere soil for the mutant isolates sampled ranged from 0 to 3.4. Twenty mutant isolates were retested in 1986. A total of 4 isolates were not detected, but the other 16 had an average root colonization value of log10 2.1 CFU and a range of log10 0.9 CFU to log10 3.2 CFU when sampled 32 days after planting. The average colonization value dropped to log10 1.1 CFU 51 days later. Some isolates detected previously were not detected in the second sampling; others had root colonization values similar to those obtained in the first sampling. Mutant isolates of rhizosphere bacteria included Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Streptomyces spp., Xanthomonas maltophilia, and a saprophytic coryneform. Mixtures of isolates from different genera and species were compatible on seeds and roots.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Debette J., Blondeau R. Présence de Pseudomonas maltophilia dans la rhizosphère de quelques plantes cultivées. Can J Microbiol. 1980 Apr;26(4):460–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutterson N. I., Layton T. J., Ziegle J. S., Warren G. J. Molecular cloning of genetic determinants for inhibition of fungal growth by a fluorescent pseudomonad. J Bacteriol. 1986 Mar;165(3):696–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.696-703.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUESTER E., WILLIAMS S. T. SELECTION OF MEDIA FOR ISOLATION OF STREPTOMYCETES. Nature. 1964 May 30;202:928–929. doi: 10.1038/202928a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloepper J. W., Scher F. M., Laliberté M., Zaleska I. Measuring the spermosphere colonizing capacity (spermosphere competence) of bacterial inoculants. Can J Microbiol. 1985 Oct;31(10):926–929. doi: 10.1139/m85-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obukowicz M. G., Perlak F. J., Kusano-Kretzmer K., Mayer E. J., Bolten S. L., Watrud L. S. Tn5-mediated integration of the delta-endotoxin gene from Bacillus thuringiensis into the chromosome of root-colonizing pseudomonads. J Bacteriol. 1986 Nov;168(2):982–989. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.982-989.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands D. C., Rovira A. D. Pseudomonas fluorescens biotype G, the dominant fluorescent pseudomonad in South Australian soils and wheat rhizospheres. J Appl Bacteriol. 1971 Mar;34(1):261–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1971.tb02285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt E. L. Initiation of plant root-microbe interactions. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1979;33:355–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.33.100179.002035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroth M. N., Hancock J. G. Disease-suppressive soil and root-colonizing bacteria. Science. 1982 Jun 25;216(4553):1376–1381. doi: 10.1126/science.216.4553.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroth M. N., Hancock J. G. Selected topics in biological control. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1981;35:453–476. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.35.100181.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanier R. Y., Palleroni N. J., Doudoroff M. The aerobic pseudomonads: a taxonomic study. J Gen Microbiol. 1966 May;43(2):159–271. doi: 10.1099/00221287-43-2-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS S. T., DAVIES F. L. USE OF ANTIBIOTICS FOR SELECTIVE ISOLATION AND ENUMERATION OF ACTINOMYCETES IN SOIL. J Gen Microbiol. 1965 Feb;38:251–261. doi: 10.1099/00221287-38-2-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wabiko H., Raymond K. C., Bulla L. A., Jr Bacillus thuringiensis entomocidal protoxin gene sequence and gene product analysis. DNA. 1986 Aug;5(4):305–314. doi: 10.1089/dna.1986.5.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynne E. C., Pemberton J. M. Cloning of a Gene Cluster from Cellvibrio mixtus which Codes for Cellulase, Chitinase, Amylase, and Pectinase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986 Dec;52(6):1362–1367. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.6.1362-1367.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T., Palm C. J., Brooks B., Kosuge T. Nucleotide sequences of the Pseudomonas savastanoi indoleacetic acid genes show homology with Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Oct;82(19):6522–6526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.19.6522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]