Abstract

Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse has been associated with subsequent (adult) sexual risk behavior, but the effects of force and type of sexual abuse on sexual behavior outcomes have been less well-studied. The present study investigated the associations between sexual abuse characteristics and later sexual risk behavior, and explored whether gender of the child/adolescent moderated these relations. Patients attending an STD clinic completed a computerized survey that assessed history of sexual abuse as well as lifetime and current sexual behavior. Participants were considered sexually abused if they reported a sexual experience (1) before age 13 with someone 5 or more years older, (2) between the ages of 13 and 16 with someone 10 or more years older, or (3) before the age of 17 involving force or coercion. Participants who were sexually abused were further categorized based on two abuse characteristics, namely, use of penetration and force. Analyses included 1177 participants (n=534 women; n=643 men). Those who reported sexual abuse involving penetration and/or force reported more adult sexual risk behavior, including the number of lifetime partners and number of previous STD diagnoses, than those who were not sexually abused and those who were abused without force or penetration. There were no significant differences in sexual risk behavior between nonabused participants and those who reported sexual abuse without force and without penetration. Gender of the child/adolescent moderated the association between sexual abuse characteristics and adult sexual risk behavior; for men, sexual abuse with force and penetration was associated with the greatest number of episodes of sex trading, whereas for women, those who were abused with penetration, regardless of whether the abuse involved force, reported the most episodes of sex trading. These findings indicate that more severe sexual abuse is associated with riskier adult sexual behavior.

Keywords: Child/adolescent sexual abuse, Sexually transmitted disease, HIV, Sexual behavior

Introduction

Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse has been associated with a wide variety of adverse mental and physical health outcomes. Research also suggests that the greater the severity of the sexual abuse, the worse the health outcomes. Thus, more severe sexual abuse (e.g., sexual abuse involving force, more intimate sexual acts, a close relative, or repeated sexual abuse) has been associated with poorer social adjustment, less life satisfaction, and more severe psychological symptoms (Callahan, Price, & Hilsenroth, 2003; Carlson, McNutt, & Choi, 2003; Fassler, Amodeo, Griffin, Clay, & Ellis, 2005; Feinauer, Mitchell, Harper, & Dane, 1996). In a meta-analysis on the effects of child sexual abuse, Rind, Tromovitch, and Bauserman (1998) found that force was associated with more negative reactions but not with later psychological symptoms, whereas penetration was unrelated to these outcomes.

Sexual abuse severity also has been associated with subsequent sexual risk behavior, including more sexual partners (Merrill, Guimond, Thomsen, & Milner, 2003) and greater likelihood of sex with someone just met, earlier age at first intercourse, and a higher frequency of STD diagnoses (Walser & Kern, 1996). Although these studies suggest that more severe sexual abuse is associated with more sexual risk behavior, they provide only limited information regarding whether specific aspects of the abuse predict such outcomes. Needed is more fine-grained research to determine whether characteristics of the abuse experience (e.g., whether physical force was used during the abuse and the type of sexual act that occurred during the abuse) are associated with sexual health outcomes.

Two studies have examined the association between sexual abuse with force and later sexual risk behavior. Cinq-Mars, Wright, Cyr, and McDuff (2003) found that adolescent girls who experienced childhood or adolescent sexual abuse with force were more likely than girls who were sexually abused without force to have engaged in subsequent consensual sex during adolescence, to have more than one partner per year, and to have been pregnant. In a sample of men who have sex with men (MSM), Jinich et al. (1998) reported that sexual abuse perceived as moderately or strongly coerced was associated with higher frequency of unprotected anal sex and higher HIV seroprevalence rates, relative to MSM who perceived the sexual abuse as voluntary or mildly coerced. Thus, in these two studies, sexual abuse involving force has been associated with greater sexual risk behavior.

Investigations of the effects of penetrative (vs. non-penetrative) sexual abuse have yielded mixed results. Cinq-Mars et al. (2003) found that adolescent girls who experienced sexual abuse involving penetration were more likely to have engaged in consensual sex and experienced an unplanned pregnancy, compared to girls who experienced non-penetrative sexual abuse. Fergusson, Horwood, and Lynskey (1997) found that, compared to participants reporting no sexual abuse, those who experienced non-penetrative sexual abuse reported higher rates of unprotected sex. However, those who experienced penetrative sexual abuse reported the worst outcomes; compared to participants who were not sexually abused, those who reported penetrative sexual abuse were more likely to have been pregnant, to report more than five sexual partners by age 18, to have had unprotected sex, and to have had an STD.

In contrast, in a meta-analysis, Arriola, Louden, Doldren, and Fortenberry (2005) found that the effect size for the relation between sexual abuse and later sexual behavior (i.e., unprotected sex, sex with multiple partners, and sex work) did not differ for studies including non-contact abuse, studies including contact abuse only, and studies including penetration abuse only; their findings suggest that type of sexual act during sexual abuse was not associated with later sexual behavior. However, some of these categories included very few studies (e.g., there were only three studies that included penetration abuse only). Furthermore, effects may have been obscured if studies with less restrictive definitions of sexual abuse included a large number of participants who had exper- ienced more severe (i.e., contact or penetrative) sexual abuse.

In sum, evidence from a small number of studies suggests that force and penetration may be associated with adult sexual risk behavior. An important limitation of previous research is that few studies have investigated the differential effects of sexual abuse for men and women. Because women in heterosexual relationships often have less control or power over sexual encounters compared to men (see the Theory of Gender and Power, Connell, 1987, for an explanation of the power imbalance between men and women), it is important to study gender in relation to sexual health behaviors. Indeed, the limited research on this topic suggests that the association between sexual abuse and adult sexual behavior differs by gender (e.g., Futterman, Hein, Reuben, Dell, & Shaffer, 1993; Mason, Zimmerman, & Evans, 1998; Zierler et al., 1991). It is possible that gender interacts with abuse characteristics to lead to different outcomes for males and females, an idea which is supported by research on the psychological sequelae of sexual abuse. For example, in a meta-analysis, Rind et al. (1998) found that whether or not the sexual abuse experience was consensual was associated with later psychological adjustment for men, but not for women. Few studies have investigated the effects of the interaction of gender and abuse characteristic on later sexual behavior. Overall, previous studies investigating the association between abuse characteristics and later sexual behavior have tended to use small samples, or included only males or only females, thus precluding gender comparisons.

The primary purpose of this study was to determine whether use of force and type of sexual act was associated with sexual risk behavior in a group of patients receiving outpatient care from a sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinic. Based on previous research, we hypothesized that: (1) the use of force; and (2) sexual abuse involving penetration would be associated with greater sexual risk behavior. The secondary purpose of this study was to determine whether the effects of abuse characteristics on adult sexual behavior differed by gender.

Method

Participants

Participants were men and women attending a public STD clinic in upstate New York. All had been screened for possible inclusion in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating several different sexual risk reduction programs. Screening criteria for the RCT included: age 18 or older; not HIV positive; and sexual behavior (e.g., unprotected sex, multiple partners) that put them at risk for contracting an STD in the past 3 months. This study used baseline data from the RCT, prior to the receipt of the interventions. Baseline data were available from 1265 eligible participants. Data from participants who refused to answer sexual abuse (n=12) or demographic (n=1) questions, were inconsistent in reporting their sexual behavior (n=5), were outliers on sexual behavior data (n=30; defined as having a studentized deleted residual >4), or were recruited in error (n=1) were eliminated. Outliers on sexual behavior data were excluded because these individuals likely were members of an extremely high-risk population that merits separate investigation (Wegener & Fabrigar, 2000).

Overall, the sample was 46% female (n=557), 65% African American (n=785), and 24% Caucasian (n=294). The majority of participants were unemployed (n=620; 51%), had a high school education or less (n=762; 63%), and had a household income of less than $15,000 per year (n=686; 57%). Most participants were single (never married; n=958; 79%); 75 participants (6%) were married, and 183 (15%) were divorced, separated, or widowed. Participants were, on average, 29.2 years of age (SD=9.7). Among women, 504 (90%) reported having sex with only men in the past 3 months; 53 (10%) reported having sex with both men and women. Among men, 612 (93%) reported having sex with only women in the past 3 months; 31 (5%) reported having sex with only men; and 15 (2%) reported having sex with both men and women in the past 3 months.

Procedure

Patients who registered for a clinic visit were invited to a private exam room by a trained research assistant (RA), and were asked to answer a series of brief screening questions. The RA explained the study to patients who met eligibility criteria and obtained informed consent. Participants then completed a 45-minute, Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) that included measures of demographic characteristics, health behaviors and beliefs, and psychosocial functioning, as well as questions about childhood sexual experiences and current sexual behavior. ACASI was used because it optimizes participant privacy (improving data quality) while allowing low-literacy persons to participate (Schroder, Carey, & Vanable, 2003). For the present study, we used data from measures of childhood/adolescent sexual abuse and sexual behavior. After their clinic exam and counseling, participants were paid $20 to compensate them for their time. All procedures were approved by the IRBs of the participating institutions.

Measures

Childhood/adolescent sexual abuse

Three items, adapted from Finkelhor’s (1979) longer survey of childhood sexual experiences, were used to assess sexual abuse (see Appendix A).1 Participants who reported any contact sexual experiences (including kissing, fondling, giving oral sex, receiving oral sex, vaginal sex, or anal sex) (1) before age 13 with someone 5 or more years older or (2) between ages 13 and 16 with someone 10 or more years older, and those who reported (3) any contact sexual experience before age 17 involving force or coercion, were classified as sexually abused; all other participants were classified as not sexually abused. Those who were sexually abused were further categorized according to whether the abuse involved force and/or penetration. Participants who reported a sexual experience before age 17 involving force or coercion were considered to have experienced sexual abuse with force. Sexually abused participants who reported any oral, vaginal, or anal sex were considered to have experienced sexual abuse with penetration. A single, four level categorical variable was created to examine the impact of different abuse characteristics on sexual risk behavior: (1) no sexual abuse; (2) sexual abuse without force or penetration; (3) sexual abuse with penetration but without force; and (4) sexual abuse with both force and penetration. Too few participants reported sexual abuse with force and without penetration (n=39, 5%) to include a sexual abuse with force only category.

Current sexual behavior

The sexual risk behavior items were developed and tested in previous studies (Carey et al., 1997, 2000, 2004). Participants were asked to report: the number of male and female sexual partners they had in their lifetime and in the past 3 months; the number of times they exchanged sex for money or drugs (lifetime); and the number of times they had been treated for an STD (lifetime).

The frequency of unprotected sex was also investigated. Participants were asked to report the number of times in the past 3 months that they had vaginal and anal sex with and without a condom with their: (1) steady partner; (2) other male partners; and (3) other female partners. Responses to these items were used to calculate the absolute number and the proportion (number of unprotected sex episodes/number of protected and unprotected sex episodes) of unprotected sex episodes in the past 3 months.

Statistical analyses

Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to determine whether the four categories of sexual abuse (no sexual abuse; sexual abuse without force or penetration; sexual abuse with penetration; and sexual abuse with both force and penetration) were associated with later risky sexual behavior. If there was a significant overall effect of sexual abuse, Tukey tests were conducted to determine specifically which groups differed. Demographic variables that differed between groups were controlled for in these analyses. Thus, the ANOVAs included: (1) demographic covariates and (2) a main effect of sexual abuse. Continuous outcome variables that were not normally distributed (i.e., the number of lifetime partners, the number of partners in the past 3 months, the number of episodes of unprotected sex in the past 3 months, the number of times participants exchanged sex for money or drugs, and the number of previous STD diagnoses) were transformed using a log10 of (x+1) transformation (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). Unless otherwise stated, analyses associated with these variables used the log transformation.

Exploratory analyses were conducted to investigate whether gender moderated the relations between the sexual abuse characteristics and later sexual behavior. ANOVAs were conducted including demographic covariates, a main effect of abuse, and the interaction of abuse and gender.

Results

Of the 1216 patients who completed the survey, 66% reported childhood/adolescent sexual abuse (n=807). Of these 807 participants who met criteria for sexual abuse, 159 (20%) reported sexual abuse without force and without penetration, 313 (39%) reported sexual abuse with penetration, 39 (5%) reported sexual abuse with force and without penetration, and 296 (37%) reported sexual abuse with both force and penetration. Because few participants reported sexual abuse with force but without penetration, those participants were excluded from the analyses, leaving a final sample size of N=1177. Sexual abuse characteristics by gender are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sexual abuse characteristics by gender

| Men (n=643) | Women (n=534) | Total (n=1177) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % of men | n | % of women | n | % of total | |

| No sexual abuse | 227 | 35 | 182 | 34 | 409 | 35 |

| Sexual abuse without force and without penetration | 100 | 16 | 59 | 11 | 159 | 14 |

| Sexual abuse with penetration only (no force) | 208 | 32 | 105 | 20 | 313 | 27 |

| Sexual abuse with both force and penetration | 108 | 17 | 188 | 35 | 296 | 25 |

Demographic differences

Preliminary analyses examined whether any demographic variables were associated with the sexual abuse characteristics (see Table 2). Sexual abuse was significantly associated with sex, race, education, and current age. Thus, for example, participants reporting a history of sexual abuse were more likely to be less well-educated and more likely to report a minority racial/ethnic identity than nonabused participants. Importantly, sexual abuse involving force and penetration was more likely to be reported by women than by men. All pairwise comparisons for the demographic characteristics are presented in Table 2. Because of these associations, sex, race, education, and current age were used as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of sexual abuse groups formed by force and penetration

| No Sexual Abusea (n=409) | Sexual Abuse (no force or penetration)b (n=159) | Sexual Abuse (penetration)c (n=313) | Sexual Abuse (force and penetration)d (n=296) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Sex (male) | 227c,d | 56 | 100d | 63 | 208a,d | 66 | 108a,b,c | 36 |

| Race (minority) | 269b,c,d | 66 | 120a,c | 75 | 279a,b,d | 89 | 228a,c | 77 |

| Education (high school or less) | 212b,c,d | 52 | 100a,c | 63 | 244a,b,d | 78 | 191a,c | 65 |

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age (in years) | 28.4d | 9.6 | 28.7 | 9.5 | 29.2 | 9.8 | 30.5a | 9.7 |

ap < .05, compared to No Sexual Abuse.

bp < .05, compared to Sexual Abuse, No Force, No Penetration.

cp < .05, compared to Sexual Abuse, No Force, Penetration.

dp < .05, compared to Sexual Abuse, Force, Penetration.

Relation between sexual abuse characteristics and sexual behavior

After controlling for relevant demographic covariates, sexual abuse was significantly associated with the number of lifetime partners, F(3, 1160)=21.08, p < .0001, the number of episodes of unprotected sex in the past 3 months, F(3, 1169)=3.97, p < .01, the number of partners in the past 3 months, F(3, 1169)=7.28, p < .0001, the number of times sex was traded, F(3, 1153)=14.23, p < .0001, and the number of previous STD diagnoses, F(3, 1169)=8.01, p < .0001 (see Table 3). Sexual abuse was not significantly associated with the proportion of unprotected sex episodes in the past 3 months.

Table 3.

Sexual risk behaviors of participants who reported sexual abuse with force, sexual abuse without force, and no sexual abuse (raw data)

| No Sexual Abusea (n=409) | Sexual Abuse (no force or penetration)b (n=159) | Sexual Abuse (penetration)c (n=313) | Sexual Abuse (force and penetration)d (n=296) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Sexual partners (number, lifetime) | 31.7c,d | 80.9 | 27.6c,d | 28.2 | 60.1a,b | 211.5 | 64.2a,b | 172.4 |

| Sexual partners (number, past 3 months) | 2.5c,d | 2.1 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 3.2a | 2.7 | 3.5a | 4.0 |

| Unprotected sex (number of events, past 3 months) | 15.3c,d | 24.3 | 17.0 | 26.8 | 20.7a | 30.1 | 22.8a | 38.2 |

| Unprotected sex (proportion, past 3 months) | 0.68 | 0.32 | 0.64 | 0.33 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.67 | 0.33 |

| Exchanged sex for money or drugs (number, lifetime) | 4.9c,d | 55.9 | 5.6d | 42.0 | 6.5a,d | 42.4 | 17.6a,b,c | 89.6 |

| STD diagnoses (number, lifetime) | 2.4c,d | 3.0 | 2.6c,d | 3.2 | 3.4a,b | 3.6 | 4.0a,b | 4.1 |

ap < .05, compared to No Sexual Abuse.

bp < .05, compared to Sexual Abuse, No Force, No Penetration.

cp < .05, compared to Sexual Abuse, No Force, Penetration.

dp < .05, compared to Sexual Abuse, Force, Penetration.

Follow-up Tukey tests showed that, compared to those who were sexually abused with penetration, those who were not sexually abused had significantly fewer: (1) lifetime sexual partners (Cohen’s d=.40); (2) partners in the past 3 months (d=.23); (3) episodes of unprotected sex in the past 3 months (d=.19); (4) episodes of sex trading (d=.31); and (5) previous STD diagnoses (d=.22; all ps < .05). Similarly, compared to those who were sexually abused with both force and penetration, those who were not sexually abused had significantly fewer: (1) lifetime sexual partners (d=.49); (2) partners in the past 3 months (d=.29); (3) episodes of unprotected sex in the past 3 months (d=.21); (4) episodes of sex trading (d=.46); and (5) previous STD diagnoses (d=.34; all ps < .05).

In addition, compared to those who were sexually abused with penetration, those who experienced sexual abuse without force and without penetration had significantly fewer lifetime sexual partners (d=.32) and fewer previous STD diagnoses (d=.17; both ps < .05). Similarly, compared to those who were sexually abused with both force and penetration, those who experienced sexual abuse without force and without penetration had significantly fewer: (1) lifetime sexual partners (d=.34); (2) episodes of sex trading (d=.29); and (3) previous STD diagnoses (d=.30; all ps < .05). Finally, those who were sexually abused with both force and penetration reported significantly more episodes of sex trading than those who were sexually abused with penetration (d=.29; p < .05).

Because sex trading likely leads to a greater number of sexual partners, episodes of unprotected sex, and STD diagnoses, follow-up analyses were conducted to determine whether penetration was still associated with the sexual behavior outcomes after controlling for sex trading. All effects remained significant after controlling for sex trading (all ps < .05).

Gender as a moderator of the relation between sexual abuse characteristics and sexual behavior

To determine whether gender moderated the relation between sexual abuse characteristics and sexual behavior, gender-by-sexual abuse interactions were included in the ANOVAs. Relevant demographic covariates were included.

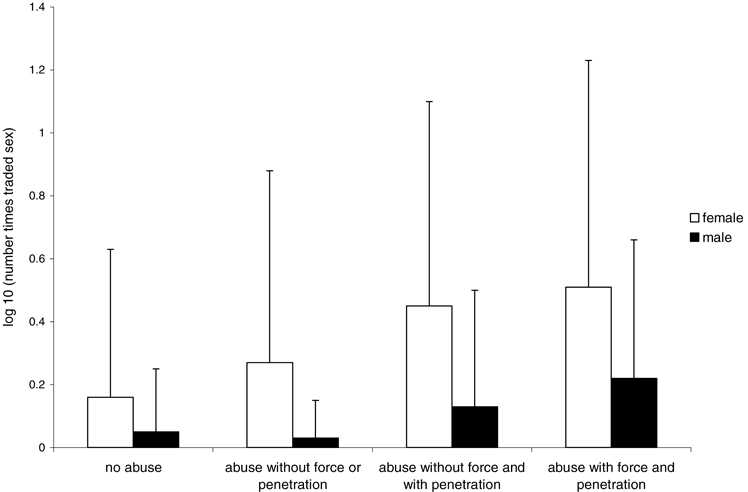

The gender-by-sexual abuse interaction was significantly associated with the number of episodes of sex trading, F(3, 1150)=3.56, p < .05. Analyses of simple main effects revealed that, for both women and men, those who were sexually abused with force and penetration reported significantly more episodes of sex trading than those who were not abused, or than those who were abused without force and without penetration. However, for women only, those who were sexually abused with penetration reported significantly more episodes of sex trading than those who were not abused (all ps < .05; see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The effect of the interaction of gender and sexual abuse status on the number of episodes of sex trading

Discussion

This study investigated whether characteristics of childhood and adolescent sexual abuse (i.e., force and type of sexual activity) were related to adult sexual risk behavior, and whether these associations differed by gender. This research benefited from several methodologic strengths. For example, we sampled a large group of both men and women who reported sexual abuse; this large and diverse sample allowed exploration of two sexual abuse characteristics and gender differences. We also used psychometrically sound measures and a computer-administered survey, known to result in higher, and presumably more candid, rates of socially stigmatized and sensitive behaviors (Schroder et al., 2003). These strengths increase confidence in the validity and generalizability of the results.

A key set of findings was that (1) sexual abuse with penetration as well as (2) sexual abuse with force and penetration were both related to higher rates of adult sexual behavior compared to (3) sexual abuse without force and without penetration and (4) no sexual abuse. This pattern of findings corroborates results from research investigating the mental health sequelae of sexual abuse, which indicate that force (e.g., Bulik, Prescott, & Kendler, 2001; Rind et al., 1998; Rodriguez, Ryan, Kemp, & Foy, 1997) and penetration (e.g., Briere & Elliott, 2003; Bulik et al., 2001) are associated with worse psychological outcomes; the current research also adds to the limited body of research suggesting a relation between force and penetration, and later sexual behavior (e.g., Cinq-Mars et al., 2003; Fergusson et al., 1997). The effect sizes for the association between sexual abuse and later sexual behavior were small to medium, indicating that other variables besides sexual abuse account for a large portion of the variance in adult sexual behavior. The latter finding is consistent with the idea that adult sexual behavior is influenced by multiple environmental as well as individual factors (Smith & Subramanian, 2006).

Penetration by itself (i.e., without force) and penetration in combination with force were associated with increased sexual risk behavior relative to those who were abused without force and without penetration, and those who were not abused. The sole difference between the penetration only and the penetration plus force groups involved sex trading, where those who experienced sexual abuse with force and penetration reported engaging in a greater frequency of sex trading, relative to those who experienced sexual abuse with penetration and no force. However, this finding was qualified by a significant gender-by-abuse interaction. Because only a very small number of participants reported sexual abuse with force but without penetration (i.e., forced kissing or fondling), we were unable to investigate the impact of force only.

A somewhat unexpected finding was that the group that reported sexual abuse without force and without penetration did not differ significantly from the nonabused group on any of the sexual behavior outcomes. Future investigation of the relation between sexual abuse and adult sexual behavior might find it fruitful to conduct more fine-grained assessments of the sexual experiences that involve only large age differentials to determine how these experiences are perceived by both men and women, and whether such experiences influence subsequent sexual behavior.

It may seem counter-intuitive that individuals who experienced more severe sexual abuse (i.e., sexual abuse with force or penetration) would engage in more sexual experiences than those who experienced less severe sexual abuse; that is, one might expect individuals who experienced severe sexual abuse to avoid sex because of the negative consequences. However, relative to individuals who experienced less severe sexual abuse, individuals who experienced more severe sexual abuse may use different strategies to cope with their sexual abuse experience(s). Thus, for both men and women, those who experienced more severe forms of sexual abuse may use alcohol or drugs to cope with the sexual abuse, which, in turn, may lead to the exchange of sex for money or drugs, and/or to a greater number of sexual partners and episodes of unprotected sex. In addition, alcohol and other drug use may lead to a greater number of sexual partners and episodes of unprotected sex due to decreased ability to attend to distal concerns, such as acquiring an STD when intoxicated or high (cf. alcohol myopia; Steele & Josephs, 1990). Indeed, we have reported previously that substance use is an important mediator of the relation between sexual abuse and risky sexual behavior (Senn, Carey, Vanable, Coury-Doniger, & Urban, 2006); future research should explore whether substance use and other potential mediators operate differently for those who experienced different severity levels of sexual abuse.

An alternative explanation for the association between more severe sexual abuse and greater adult sexual risk behavior is Finkelhor and Browne’s (1985) traumagenic dynamics model. This model proposes that one consequence of sexual abuse is traumatic sexualization, in which a child develops maladaptive scripts for sexual behavior, when rewarded for sexual behavior by affection. More severe sexual abuse, such as sexual abuse involving force or penetration, may lead to greater traumatic sexualization. As adults, those who experienced traumatic sexualization may believe sex is necessary to obtain affection from others. Thus, traumatic sexualization may lead to, for example, earlier consensual sex or a greater number of sexual partners (e.g., Cinq-Mars et al., 2003; Fergusson et al., 1997).

Another consequence of sexual abuse, according to Finkelhor and Browne (1985), is powerlessness, in which a child learns that his or her needs or requests are ignored by others; the child thus fails to develop self-efficacy to stop unwanted sexual advances. More severe sexual abuse, particularly sexual abuse involving force or penetration, may lead to greater feelings of powerlessness. Perhaps because they lack the interpersonal skills or the self-efficacy to stop unwanted sexual advances, these individuals may be less likely to refuse intercourse with aggressive partners, resulting in more sexual partners. Powerlessness could help explain findings linking more severe sexual abuse to more adult sexual risk behavior (e.g., Cinq-Mars et al., 2003; Fergussion et al., 1997). In this regard, Kallstrom-Fuqua, Weston, and Marshall (2004) found that sexual abuse severity had an indirect effect on maladaptive relationships, mediated through powerlessness; thus, having many sexual partners could be a consequence of difficulty forming close relationships. Further research is needed to examine whether the sexual abuse characteristics investigated in this study are associated with Finkelhor and Browne’s (1985) traumagenic dynamics.

Another finding yielded by this study is that abuse characteristics were associated with different outcomes for men and women. For men, only abuse with both force and penetration was associated with a greater frequency of sex trading, whereas for women, abuse with penetration, regardless of whether or not force was involved, was associated with more sex trading. In the current cultural context, young males may view sex with an older woman as masculine and mature, rather than abusive. Males, therefore, may tend to view only experiences involving force or coercion as abusive. Women, on the other hand, may be more likely to view intercourse with an older individual as abusive, regardless of whether or not force was involved. This idea is supported by meta-analytic findings that boys’ reactions to sexual abuse were less negative than were girls’ reactions (Rind et al., 1998). Different perceptions of whether or not the experience was abusive may lead to the use of different coping strategies.

These results should be interpreted mindful of the limitations of the study. One limitation involved the brevity of the sexual abuse assessment. Use of a brief survey allowed us to obtain a large and diverse sample, but limited the richness of the data collected. The survey did not assess other aspects of sexual abuse, such as duration, frequency, and relationship to the perpetrator, which may be important correlates of later outcomes (e.g., Banyard & Williams, 1996; Briere & Elliott, 2003). In addition, these brief questions did not allow for assessment of reactions to the sexual experience; many participants, especially those who did not report force or coercion, may not have considered themselves sexually abused, but may have viewed these sexual experiences as inconsequential or even consensual. Future research, involving mixed qualitative and quantitative methods, might help to elucidate the empirical relations observed in the current sample.

A second limitation involves the correlational nature of the data. Clearly, such data limit causal inferences, although given the temporal sequence of childhood/adolescent sexual abuse and adult sexual behavior, the limits may be less concerning in this context. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that unexplored variables that are related to both sexual abuse and greater sexual risk behavior (e.g., more adverse childhood experiences; Dong, Anda, Dube, Giles, & Felitti, 2003) should be included in future investigations of the sexual abuse–risky sex relation.

It is important to recognize that participants in this study were recruited from a sexually transmitted disease clinic, and were included because they were currently engaging in sexual behavior that conferred risk for contracting an STD. The rates of sexual abuse reported in this sample were considerably higher than rates (i.e., 15% for men and 30% for women) reported in national samples (Briere & Elliott, 2003; Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1990; Vogeltanz et al., 1999). In addition to engaging in sexual risk behavior, patients attending STD clinics may differ from the general population in other important ways as well; for example, patients attending STD clinics often report extremely high rates of alcohol and drug use (Cook et al., 2006). Due to the nature of the sample, these results of the present study may not generalize to other populations.

These results have implications for both practice and research. Regarding public health and clinical practice, they suggest that a thorough sexual health assessment should include inquiry about the nature of the sexual abuse, particularly whether force was involved and what type of sexual act occurred. Given the likely impact of sexual abuse on sexual risk behavior (as well as other health outcomes), we recommend a more comprehensive approach to sexual health assessment, education, counseling, and/or therapy. Indeed, these findings highlight the need to develop interventions tailored to the unique needs of persons with a history of sexual abuse to promote (and restore) sexual health and reduce sexual risk. With respect to research, these findings raise many questions about the conditions under which sexual abuse impairs healthy sexual development and expression, and about the mechanisms by which sexual abuse influences sexual development, behavior, and adjustment. This work will require sophisticated methods and analyses to overcome the limitations of what is inherently retrospective and correlational research.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients for their participation as well as the staff at the Monroe County STD Clinic and the Health Improvement Project team for their contributions to this work. Supported by a grant R01-MH54929 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Appendix A

Child/Adolescent Sexual Abuse Questions

Before you were 13, which types of sexual activity did you have with anyone who was 5 or more years older than you? Check all that apply.

kissing

fondling

receiving oral sex

giving oral sex

vaginal sex

anal sex

none of the above

Between the ages of 13 and 16, which types of sexual activity did you have with anyone who was 10 or more years older than you? Check all that apply.

kissing

fondling

receiving oral sex

giving oral sex

vaginal sex

anal sex

none of the above

Before you were 17, were you ever forced or coerced into any of the following types of sexual activity? Check all that apply.

kissing

fondling

receiving oral sex

giving oral sex

vaginal sex

anal sex

none of the above

Footnotes

Although the questions assessing sexual abuse included complex words, the majority of participants (n=719, 61%) scored a 61 or above (out of a possible 66) on the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM; Davis et al., 1993). A score of 61 or above is consistent with a high school reading level. The average score on the REALM was 57.9 (SD=11.7), which is consistent with a seventh to eighth grade reading level.

References

- Arriola, K. R. J., Louden, T., Doldren, M. A., & Fortenberry, R. M. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship of child sexual abuse to HIV risk behavior among women. Child Abuse and Neglect, 29, 725–746. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Banyard, V. L., & Williams, L. M. (1996). Characteristics of child sexual abuse as correlates of women’s adjustment: A prospective study. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 853–865. [DOI]

- Briere, J., & Elliott, D. M. (2003). Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27, 1205–1222. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bulik, C. M., Prescott, C. A., & Kendler, K. S. (2001). Features of childhood sexual abuse and the development of psychiatric and substance use disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 179, 444–449. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Callahan, K. L., Price, J. L., & Hilsenroth, M. J. (2003). Psychological assessment of adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse within a naturalistic clinical sample. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80, 173–184. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Carey, M. P., Braaten, L. S., Maisto, S. A., Gleason, J. R., Forsyth, A. D., & Durant, L. E. (2000). Using information, motivational enhancement, and skills training to reduce the risk of HIV infection for low-income urban women: A second randomized clinical trial. Health Psychology, 19, 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Carey, M. P., Carey, K. B., Maisto, S. A., Gordon, C. M., Schroder, K. E., & Vanable, P. A. (2004). Reducing HIV-risk behavior among adults receiving outpatient psychiatric treatment: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 252–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carey, M. P., Maisto, S. A., Kalichman, S. C., Forsyth, A. D., Wright, E. M., & Johnson, B. T. (1997). Enhancing motivation to reduce the risk of HIV infection for economically disadvantaged urban women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 531–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carlson, B. E., McNutt, L., & Choi, D. Y. (2003). Childhood and adult abuse among women in primary health care: Effects on mental health. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18, 924–941. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cinq-Mars, C., Wright, J., Cyr, M., & McDuff, P. (2003). Sexual at-risk behaviors of sexually abused adolescent girls. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 12, 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Connell, R. W. (1987). Gender and power: Society, the person, and sexual politics. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Cook, R. L., Comer, D. M., Wiesenfeld, H. C., Chang, C. C., Tarter, R., Lave, J. R., & Clark, D. B. (2006). Alcohol and drug use and related disorders: An underrecognized health issue among adolescents and young adults attending sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 33, 565–570. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Davis, T. C., Long, S. W., Jackson, R. H., Mayeaux, E. J., George, R. B., Murphy, P. W., et al. (1993). Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine: A shortened screening instrument. Family Medicine, 25, 391–395. [PubMed]

- Dong, M., Anda, R. F., Dube, S. R., Giles, W. H., & Felitti, V. J. (2003). The relationship of exposure to childhood sexual abuse to other forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction during childhood. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27, 625–639. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fassler, I. R., Amodeo, M., Griffin, M. L., Clay, C. M., & Ellis, M. A. (2005). Predicting long-term outcomes for women sexually abused in childhood: Contributions of abuse severity versus family environment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 29, 269–284. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Feinauer, L. L., Mitchell, J., Harper, J. M., & Dane, S. (1996). The impact of hardiness and severity of childhood sexual abuse on adult adjustment. American Journal of Family Therapy, 24, 206–214. [DOI]

- Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., & Lynskey, M. T. (1997). Childhood sexual abuse, adolescent sexual behaviors and sexual revictimization. Child Abuse and Neglect, 21, 789–803. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Finkelhor, D. (1979). Sexually victimized children. New York: The Free Press.

- Finkelhor, D., & Browne, A. (1985). The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 55, 530–541. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Finkelhor, D., Hotaling, G., Lewis, I. A., & Smith, C. (1990). Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse and Neglect, 14, 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Futterman, D., Hein, K., Reuben, N., Dell, R., & Shaffer, N. (1993). Human immunodeficiency virus-infected adolescents: The first 50 patients in a New York City program. Pediatrics, 91, 730–735. [PubMed]

- Jinich, S., Paul, J. P., Stall, R., Acree, M., Kegeles, S., Hoff, C., et al. (1998). Childhood sexual abuse and HIV risk-taking behavior among gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior, 2, 41–51. [DOI]

- Kallstrom-Fuqua, A. C., Weston, R., & Marshall, L. L. (2004). Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse of community women: Mediated effects on psychological distress and social relationships. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 980–992. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mason, W. A., Zimmerman, L., & Evans, W. (1998). Sexual and physical abuse among incarcerated youth: Implications for sexual behavior, contraceptive use, and teenage pregnancy. Child Abuse and Neglect, 22, 987–995. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Merrill, L. L., Guimond, J. M., Thomsen, C. J., & Milner, J. S. (2003). Child sexual abuse and number of sexual partners in young women: The role of abuse severity, coping style, and sexual functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 987–996. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rind, B., Tromovitch, P., & Bauserman, R. (1998). A meta-analytic examination of assumed properties of child sexual abuse using college samples. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 22–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, N., Ryan, S. W., Kemp, H. V., & Foy, D. W. (1997). Posttraumatic stress disorder in adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse: A comparison study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schroder, K. E. E., Carey, M. P., & Vanable, P. A. (2003). Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. Accuracy of self-reports. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 26, 104–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Senn, T. E., Carey, M. P., Vanable, P. A., Coury-Doniger, P., & Urban, M. A. (2006). Childhood sexual abuse and sexual risk behavior among men and women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 720–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Smith, A. M. A., & Subramanian, S. V. (2006). Population contextual associations with heterosexual partner numbers: A multilevel analysis. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82, 250–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Steele, C. M., & Josephs, R. A. (1990). Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist, 45, 921–933. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Vogeltanz, N. D., Wilsnack, S. C., Harris, T. R., Wilsnack, R. W., Wonderlich, S. A., & Kristjanson, A. F. (1999). Prevalence and risk factors for childhood sexual abuse in women: National survey findings. Child Abuse and Neglect, 23, 579–592. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Walser, R. D., & Kern, J. M. (1996). Relationships among childhood sexual abuse, sex guilt, and sexual behavior in adult clinical samples. Journal of Sex Research, 33, 321–326.

- Wegener, D. T., & Fabrigar, L. R. (2000). Analysis and design for nonexperimental data: Addressing causal and noncausal hypotheses. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 412–450). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Zierler, S., Feingold, L., Laufer, D., Velentgas, P., Kantrowitz-Gordon, I., & Mayer, K. (1991). Adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse and subsequent risk of HIV infection. American Journal of Public Health, 81, 572–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]