Abstract

The detection of virulence determinants harbored by pathogenic Escherichia coli is important for establishing the pathotype responsible for infection. A sensitive and specific miniaturized virulence microarray containing 60 oligonucleotide probes was developed. It detected six E. coli pathotypes and will be suitable in the future for high-throughput use.

Pathogenic Escherichia coli strains constitute a significant public health problem worldwide (12). In contrast to their nonpathogenic counterparts, these strains have acquired specific virulence attributes that allow them to cause a spectrum of human and animal illnesses (10, 15). Numerous methods exist for the detection of pathogenic E. coli, including geno- and phenotypic marker assays for the detection of virulence genes and their products (7, 17, 21, 23). These methods have the common drawback of screening a relatively small number of determinants simultaneously. DNA microarrays offer a viable alternative due to their ability to screen multiple markers simultaneously.

The aim of this work was to develop a simple high-throughput system based in a microtube (details are available from CLONDIAG, Jena, Germany) (13, 20) for pathotyping E. coli isolates sent to clinical diagnostic laboratories.

Design and validation of miniaturized virulence arrays.

A miniaturized E. coli oligonucleotide virulence array was designed containing 39 virulence, 7 bacteriocin, and 15 control (rrl and gad) gene probes (Table 1). Eighteen genes were specific to a particular E. coli pathotype, 13 were common between 2 or more pathotypes, and 7 were unassigned. The design of probes/primers and the specificity were tested as previously described (1, 13).

TABLE 1.

Probes and primers used in the miniaturized microarraya

| Probe/gene | Probe/gene function | Target gene accession no. | Pathotype(s)b | Control strain (origin or reference)e | Probe sequence (5′-3′) | Primer sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| astA | Heat-stable enterotoxin | AE005345.1 | EAEC, ETEC | Abbotstown (22) | ||

| astA_11 | TCgTgCATATGGTGCgCAACAG | GACGGCTTTGTAgTCCTTCC | ||||

| astA_21 | TCgTgCATATGGTGCgCAACAG | TGACGGCTTTGTAtTCCTTCC | ||||

| bfpA | Major subunit of bundle-forming pili | AB024946.1 | EPEC | E2348/69 (16) | GGTGTGATGTTTTACTACCAGTCTGC | CGCTCATTACTTCTGAAATaGCA |

| cba | Colicin B pore forming | M16816.1 | Undesignated | EC2334/03 (VLA) | GGATGGTCTGTCAGTGTGCACG | GCGGAAACTTTCTCGTTTCC |

| cdtB | Cytolethal distending toxin B | AJ508930.1 | EPEC, STEC, ETEC, ExPEC* | EC934/04 (VLA) | ||

| cdtB_40 | GCTGTTGATGCCtTtGGTGGAAG | GCTAACCAGAGCAAGATTGAC | ||||

| cdtB_50 | GCTGTTGATGCCcTtGGTGGAAG | |||||

| celb | Endonuclease colicin E2 | X03632.1 | Undesignated | EC2334/03 (VLA) | GGACCGTATCTCCGTCATCAACAG | GCGTTGCTAATCCGGTCAC |

| cfaC | Colonization factor antigen I | M55661.1 | ETEC | IMI100 (Bern) | GGAATAGCGCGCTGGGTATTACAGA | TCATCCACCAATTTAAGACAGC |

| cma | Colicin M, resembles beta-lactam antibiotics | M16754.1 | Undesignated | EC2334/03 (VLA) | TGTAACGCCGACCGAAATCTGGT | TCATAAACGCTTATTCCAGGGT |

| cnf | Cytotoxic necrotizing factor | AF483828.1 | ExPEC* | S5 (8) | CTTCCAGTATGGGGATCAGTTTTGATCA | CGACGTTCTTCATAAGTATCACC |

| eaec | Intimin | AJ579371.1 | EPEC, EHEC | E2348/69 (25) | ||

| eae_10 | GTTACAaCaTTATGGAACGGCAGAGGT | CgTCAAAGTTATtACCaCTCTGC | ||||

| eae_20 | GTTACAaCgTTATGGAACGGCAGAGG | AGTcTCGCCAgTATTCgC | ||||

| eae_30 | TGGTgAtAATACCCGtTTAGGtATtGGt | |||||

| eae_40b | TGGTgAtAATACCCGcTTAGGtATtGG | |||||

| f17Ac | Subunit A of F17 fimbrial protein | AF022140.1 | ETEC, ExPEC* | CK210 (6), S5 (8) | ||

| f17A_40b | ggTAcTAtGCaACgGgtcaGGC | TGATAAgCGATGGTGTAATTcACaG | ||||

| f17A_50b | CagTAcTAcGCaACgGgtgtGG | TGATAAgCGATGGTGTAATTaACtG | ||||

| f17A_60b | aCaaTAtTAtGCcACaGcgccGG | CTGATAAaCGATGGTGTAATTtACtG | ||||

| f17G | Adhesin subunit of F17 fimbrial protein | AF022140.1 | ETEC, ExPEC* | CK210 (6) | TGCAATGGATAACCTGCCATTTGTCT | CCAGACATTTGCATTCTGATATCC |

| fanA | Involved in biogenesis of K99/F5 fimbriae | X05797.1 | ETEC | ETEC562 (VLA) | AGCAAGGTGCTTCCAATTATTAGTGGA | CGTAAATACCCCTAGAACTACGT |

| fasA | Fimbrial 987P/F6 subunit | M35257.1 | ETEC | HM1535 (VLA) | GCCAAGTGGATACTTCTAATCTGTCGC | GAGCAGAAGTAGACAACTCTCC |

| fim41a | Mature Fim41a/F41 protein | X14354.1 | ETEC | ETEC562 (VLA) | GGCTTGTTAATCCAGGTCGATTTACTG | GAGAGTCCATTCCATTTATAGGCT |

| gad | Glutamate decarboxylase | M84025.1 | All E. coli | All | GATATCGTCTGGGACTTCCGCCT | TGAAGCACTGATCGATTTCACA |

| ehx (hlyA) | Hemolysin A | AB011549.2 | EPEC, EHEC | EDL933 (19) | TGTAGGATTAACTGAACGTGGTGTTGC | GCAGAAGTTTGTCAAGTTGTGG |

| hlyE | Avian E. coli hemolysin | AF052225.1 | ExPEC* | M1000 (14) | CCAAGATAGATACTTCGAGGCGACAC | TCACTCCACACCATTCATAAACT |

| ipaH9.8 | Invasion plasmid antigen | AF047365.1 | Shigella sonnei | NCTC8192 (HPA)** | TCGCGCTCACATGGAACAATCTC | GCCTGATGGACCAGGAGG |

| ireA | Siderophore receptor | AF320691.1 | ExPEC* | CFT073 (24) | CCACAAATGACTTCTATCTGTCAGGC | CTCCATATAGCTGAAGACCAAGT |

| iroN | Enterobactin siderophore receptor protein | AF449498.1 | ExPEC* | CFT073 (24) | GCCTGTCGAGTAACATGATCAATGCT | GAGGCTTTGCGAAGTGAGC |

| iss | Increased serum survival | AF042279.1 | ExPEC* | CFT073 (24) | CCGCTCTGGCAATGCTTATTACAGG | gGTTTGTTTccAACAGTAAACGT |

| K88ab | K88/F4 protein subunit gene | V00292.1 | ETEC | Abbotstown (22) | GCCTGGATGACTGGTGATTTCAATGG | GTGATACTACCACCGATATCGAC |

| lngA | Longus type IV pilus | AF004308.1 | ETEC | B1308 (VLA) | CGTCTGGTTCATATGCCATGACAGC | CCACAGACATATCTACACCAGT |

| lthA | Heat-labile enterotoxin A subunit | AB011677.1 | ETEC | ETEC21d (VLA) | GGTTTCTGCGTTAGGTGGAATACCA | ACCAAAATTAACACGATACCATCC |

| mchB | Microcin H47 part of colicin H | AJ515252.1 | Undesignated | CFT073 (24) | GGTTGTAGTTGGAGCCGTATCTGC | GGTCGAGCCAATTGCTGT |

| mchC | MchC protein | AJ515252.1 | Undesignated | CFT073 (24) | CTGTCGGGTTAGATCTGTGATCCAC | CCGGTGGTACAGGTAGATATCC |

| mchF | ABC transporter protein MchF | AJ515251.1 | Undesignated | CFT073 (24) | TCCGGTTATTCATCAGACGGAGACC | CAAAATGACCGCATATCATTGC |

| mcmA | Microcin M part of colicin H | AJ515251.1 | Undesignated | CFT073 (24) | CCTCCATGTCTCCCTCAGGTATAGG | GGCACTTGATGTACCTCTGC |

| perAc | EPEC adherence factor, transcriptional activator | |||||

| perA_10 | AF255772.1 | EPEC | E2348/69 (16) | TGTTTGGTTGGGTTTAATTCCACATCA | TTGGTGTTGTGTTGTAATATTCCT | |

| perA_20 | N1743-95 (Bern) | GCTTGGTTGGTTTTAATTCCACGTC | ||||

| pet | Autotransporter enterotoxin | AF056581.1 | EAEC | NZ1470-95 (Bern) | GCTGACAAGGATAATTCTGCCACAAGA | GCATCGCGAGAGCAAACT |

| prfB/papB | P-related fimbriae regulatory gene | X76613.1 | ExPEC* | CFT073 (24) | GGGAGACTTATACGGCTGAATGCTC | TCATCTGTATAATAAGGTGCAAGC |

| senB | Plasmid-encoded enterotoxin | Z54195.1 | EIEC | NCTC9774 (HPA) | GCTCTATATCGGACACACCCAGTCAG | GGTGTCAAACATACTGATACGC |

| sfaS | S fimbria minor subunit | X16664.4 | ExPEC* | E536 (VLA) | CAATGCAGGAAGTGGATCTCCATGG | TCCGGTGAGAGACAGATCA |

| sta1Ac | Heat-stable enterotoxin ST-Ia | |||||

| sta1A_111 | AJ555214.1 | ETEC | ETEC562 (VLA) | ACACATTTTACTGCTGTGAACTTTGTTG | AACATggAGCACAGGCAG | |

| sta1A_121 | AACATccAGCACAGGCAG | |||||

| sta1B | Heat-stable enterotoxin ST-Ib | AY342058 | ETEC | IMI100 (Bern) | AGCAATTACTGCTGTGAATTGTGTTGT | AGCACCCGGTACAAGCAG |

| stb | Heat-stable enterotoxin II | AJ555214.1 | ETEC | Abbotstown (22) | GAGATGGTACTGCTGGAGCATGCT | TTGCTGCAACCATTATTTGGG |

| stx1A | Shiga toxin 1 A subunit | AB035142.1 | STEC | EDL933 (19) | GTGACAGTAGCTATACCACGTTACAGC | TCTGCATCCCCGTACGAC |

| stx2A | Shiga toxin 2 A subunit | AB035143.1 | STEC | EDL933 (19) | GCAGTTATACCACTCTGCAACGTGTC | CtgAttTGCATtCCgGaACG |

| virF | VirF transcriptional activator, ipaBCD-positive regulator | AF386526.1 | Shigella flexneri | NCTC8192 (HPA)** | GCCTTTTATCAGCTGTTTCTGATGAGGA | GAGAAGAAGCTATCGATATCGAAGT |

| rrl_0101_0177_10 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | GTGTGTTTCGACACACTATCATTAACTGA | GGTTCGCCTCATTAACCTATGG |

| rrl_0101_0177_20 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | GTGTGATTCGTCACACTATCATTAACTGA | |

| rrl_0260_0330_10 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | CAGAGCCTGAATCAGTATGTGTGTTAGT | GCCTTTCCAGACGCTTCC |

| rrl_0260_0330_20 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | GAGCCTGAATCAGTGTGTGTGTTAGT | |

| rrl_0260_0330_30 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | AGAGCCTGAATCAGTTTGTGTGTTAGT | |

| rrl_0520_0580_10 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | GCAGTGGGAGCACGCTTAGG | AAGGTACGCAGTCACACG |

| rrl_0520_0580_20 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | AAGCAGTGGGAGCATGCTTAGG | |

| rrl_1480_1560_coli_10 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | CCGGAAAATCAAGGATGAGGCGTG | CACCGTAGTGCCTCGTCA |

| rrl_1480_1560_coli_20 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | CGGAAAATCAAGGCTGAGGCGTG | |

| rrl_1480_1560_coli_30 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | GGAAAACCAAGGCTGAGGCGTG2 | |

| rrl_1480_1560_shig_40 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | GGAAAATCAAGGCCGAGGCGTG | |

| rrl_1690_1770_coli_10 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | GCTGATATGTAGGTGAAGCGACTTGC | CGACTGATTTCAGCTCCACG |

| rrl_1690_1770_freu_30 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | CGCTGATATGTAGGTGAAGTGGTTTACT | |

| rrl_1690_1770_shig_20 | 23S rRNA (large rRNA) | M25458.1 | All | E2348/69d | GCTGATACGTAGGTGAAGCGACTTG |

All probes and primers present in the array representing genes or encompassing allelic variations are listed. The description for each gene, the accession number of the target gene used initially for probe/primer design, the pathotype associated with each gene, and the positive control strain are also given. Probes for the 23S rRNA gene (rrl) were included as a species marker, while the gad gene was included as an invariant positive control present in low copy number in all E. coli strains. *, uropathogenic E. coli, avian pathogenic E. coli, and neonatal meningitis E. coli have been classed together as extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) for this study; **, Health Protection Agency, National Culture Typing Collection. Lowercase letters in sequences indicate sequence variability within the consensus region within which the probe or primer was designed.

EAEC, enteroaggregative E. coli; ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli; EPEC, enteropathogenic E. coli; STEC, shigatoxigenic E. coli; EHEC, enterohemorrhagic E. coli; EIEC, enteroinvasive E. coli. “All” indicates all E. coli.

Polymorphic genes where different control strains were found to bind to different probe sets or probes showed different signal intensities reflecting allelic variation that had not been distinguished by PCR (see the supplemental material for details).

For details, see www.sanger.ac.uk.

HPA, Health Protection Agency; VLA, Veterinary Laboratories Agency.

Control strains were used to validate each probe present on the array (Table 1). PCR amplification and sequencing, using primers given in Appendix 1 of the supplemental material, verified the presence of the probes in control strains. The sequenced genes showed between 92 and 100% sequence identity to the respective target gene and showed 100% sequence identity to the probe and primer regions (data not shown).

Genomic DNA was extracted from cells grown aerobically overnight at 37°C in LB broth, using a DNeasy tissue kit (catalog no. 69504; QIAGEN). One microgram of genomic DNA from each strain was used as a template in a multiplex linear amplification and labeling reaction with the set of 60 primers (Table 1), as previously described (1). The amplified products were added to ArrayTubes for hybridizations performed according to the method of Ballmer et al. (1, 13).

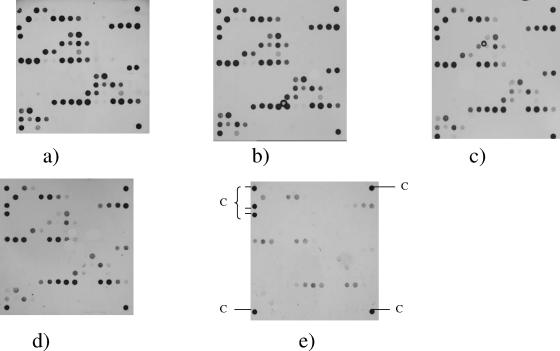

The sequenced strains EDL933, CFT073, and E2348/69 were used to estimate assay sensitivity to ensure strong signal intensity with minimal nonspecific cross-hybridization. Optimization included varying the concentrations of genomic DNA used for labeling (2 to 0.05 μg), the primers present in the linear multiplex mix (0.135 to 0.810 μM), and the poly-horseradish peroxidase-streptavidin conjugate used for detecting hybridization (50 to 400 pg/μl). The minimal concentration of genomic DNA found to reliably detect all expected genes was 1.0 μg, while a concentration of 0.135 μM per primer in the stock solution was sufficient for the detection of target DNA (Fig. 1). The optimal concentration of poly-horseradish peroxidase-streptavidin conjugate was found to be 200 pg/μl; concentrations above or below this value resulted in high background or no detectable reaction at all (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Optimization of the genomic concentration used in this study. The optimal concentration of genomic DNA from EDL933 used for the detection of genes on the virulence oligonucleotide miniaturized microarray chip was assessed using (a) 2 μg, (b) 1 μg, (c) 0.5 μg, (d) 0.1 μg, and (e) 0.05 μg of DNA. The six biotinylated marker spots (C) are visible in all arrays. A concentration of 0.135 μM per primer in the stock solution and 200 pg/μl of poly-horseradish peroxidase-streptavidin conjugate were used for these assays.

The spot signal intensity was derived by calculating the quantitative staining value with IconoClust software (version 2; CLONDIAG). The data were normalized using the signal intensity of the gad probe, and the normalized signal intensity for genes within positive and negative control strains was used to differentiate between present (signal intensity value above 0.4) and absent (signal intensity value below 0.3) genes. Genes with signal intensity values between 0.3 and 0.4 were considered ambiguous. Two replicate hybridizations were performed for each control strain, and the 95% confidence interval of error across replicate hybridizations was 1.6 to 3% (see Appendix 2 in the supplemental material).

The specificity of each probe was estimated by comparing array data with PCR and sequenced data from control strains. In all cases, the virulence gene(s) known to be present within positive control strains was clearly identified by array, while two negative control strains, including the sequenced strain MG1655, showed the presence of only 23S rRNA and gad genes (see Appendix 2 in the supplemental material). For many positive control strains, additional virulence genes were detected (Table 2). Furthermore, PCR amplification in all control strains of five randomly chosen genes (eae, astA, ehx or hlyA, iss, and mcmA), showed 100% correlation between array and PCR data, indicating the probes to be highly specific with minimum cross-reactions (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Virulence determinants detected within each positive control strain

| Virulence gene | Gene presence ina:

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbotstown | E2348/69 | EC2334/03 | EC934/04 | IMI100 | S5 | EDL933 | CFT073 | CL394 | ETEC562 | HM1535 | M1000 | NCTC9774 | B1308 | ETEC21d | NZ1470-95 | E536 | N1743-95 | NCTC8192 | |

| astA | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| bfpA | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| cba | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| cdtB_40 | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| cdtB_50 | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| celb | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| cfaC | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| cma | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| cnf | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| eae_10 | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| eae_20 | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| eae_30 | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| eae_40 | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| f17A_40 | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| f17A_50 | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| f17A_60 | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| f17G | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| fanA | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| fasA | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| fim41a | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| ehx (hlyA) | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| hlyE | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| ipaH9.8 | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| ireA | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| iroN | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| iss | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| K88ab | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| lngA | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| lthA | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| mchB | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| mchC | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| mchF | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| mcmA | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| perA_10 | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| perA_20 | |||||||||||||||||||

| pet | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| prfB/papB | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| senB | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| sfaS | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| sta1A | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| sta1B | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| stb | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| stx1A | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| stx2A | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| virF | X | ||||||||||||||||||

The X's indicate virulence genes present in each positive control strain from using the virulence gene pathoarray, while clear boxes indicate absent genes. The control rrl and gad genes have been omitted for clarity; see the supplemental material for full details. The mean number of virulence determinants found in the control set of strains was 5, with the highest and lowest numbers being 9 and 1, respectively.

Pathotyping clinical isolates.

A panel of 63 E. coli human and animal clinical isolates were pathotyped using the virulence miniaturized microarray (see Appendix 3 in the supplemental material). For five strains, two hybridization reactions were performed and the 95% confidence interval of error between replicates was 0.9 to 5.0%. Only one hybridization reaction was performed for the remaining test strains.

Fifty-five of the isolates hybridized to more than one virulence determinant and were readily designated within a recognized pathotype, mostly matching the clinical diagnosis where available. Five isolates that harbored only the iss gene and/or microcins and three isolates that hybridized to only control genes could not be pathotyped. These isolates may harbor virulence genes not present on our array. Several isolates with novel combinations of genes were detected and included two shigatoxigenic E. coli strains, one with senB, iss, cma, cba, and mchBCF genes and another with astA, cdtB, and cnf genes. The most commonly detected gene was iss, which was present in half the strains tested. Other genes which were detected in at least 10 or more isolates included eae, ehx, astA, iroN, mchF, mchB, mchC, f17A (three variants combined), f17G, mcmA, cba, cma, and prfB/papB. Genes virF, pet, hlyE, fasA, and cfa were not detected in any test isolate (see Appendix 3 in the supplemental material).

Conclusion.

Several E. coli virulence arrays for genotyping have been described previously (2-5, 9, 11, 18). These arrays use mostly a glass slide printed with oligonucleotide probes or PCR products for target genes and fluorescent Cy dyes to label DNA used for hybridization. This system is time consuming, with expensive reagents and requires a skilled technician. In contrast, the microtube-based array system used in this study has a short assay time due to an amplification step and inexpensive reagents and requires low technical skills, making it amenable for use in clinical diagnostic laboratories. In the future, the routine use of virulence microarrays in such laboratories will not only allow rapid detection and designation of the pathotypes of strains sent to diagnostic laboratories but also enable emergent strains harboring novel virulence combinations to be detected before such strains spread to become a health problem.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Enteric Reference Laboratory at VLA for the provision of E. coli strains and in particular to Katherine Sprigings and Louise Finch. We thank Elke Müller and Jana Sachtschal for their assistance.

This project was funded through the VLA seedcorn fund.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 July 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ballmer, K., B. M. Korczak, P. Kuhnert, P. Slickers, R. Ehricht, and H. Hachler. 2007. Fast DNA serotyping of Escherichia coli by use of an oligonucleotide microarray. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:370-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruant, G., C. Maynard, S. Bekal, I. Gaucher, L. Masson, R. Brousseau, and J. Harel. 2006. Development and validation of an oligonucleotide microarray for detection of multiple virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3780-3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Call, D. R., F. J. Brockman, and D. P. Chandler. 2001. Detecting and genotyping Escherichia coli O157:H7 using multiplexed PCR and nucleic acid microarrays. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 67:71-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, S., S. Zhao, P. F. McDermott, C. M. Schroeder, D. G. White, and J. Meng. 2005. A DNA microarray for identification of virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes in Salmonella serovars and Escherichia coli. Mol. Cell. Probes 19:195-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chizhikov, V., A. Rasooly, K. Chumakov, and D. D. Levy. 2001. Microarray analysis of microbial virulence factors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3258-3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cid, D., R. Sanz, I. Marin, H. de Greve, J. A. Ruiz-Santa-Quiteria, R. Amils, and R. de la Fuente. 1999. Characterization of nonenterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains producing F17 fimbriae isolated from diarrheic lambs and goat kids. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1370-1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark, C. G., S. T. Johnson, R. H. Easy, J. L. Campbell, and F. G. Rodgers. 2002. PCR for detection of cdt-III and the relative frequencies of cytolethal distending toxin variant-producing Escherichia coli isolates from humans and cattle. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2671-2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Rycke, J., E. A. Gonzalez, J. Blanco, E. Oswald, M. Blanco, and R. Boivin. 1990. Evidence for two types of cytotoxic necrotizing factor in human and animal clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:694-699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenkins, C., C. van Ijperen, E. G. Dudley, H. Chart, G. A. Willshaw, T. Cheasty, H. R. Smith, and J. P. Nataro. 2005. Use of a microarray to assess the distribution of plasmid and chromosomal virulence genes in strains of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 253:119-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaper, J. B., J. P. Nataro, and H. L. Mobley. 2004. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:123-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korczak, B., J. Frey, J. Schrenzel, G. Pluschke, R. Pfister, R. Ehricht, and P. Kuhnert. 2005. Use of diagnostic microarrays for determination of virulence gene patterns of Escherichia coli K1, a major cause of neonatal meningitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1024-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mead, P. S., L. Slutsker, V. Dietz, L. F. McCaig, J. S. Bresee, C. Shapiro, P. M. Griffin, and R. V. Tauxe. 1999. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:607-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monecke, S., and R. Ehricht. 2005. Rapid genotyping of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates using miniaturised oligonucleotide arrays. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11:825-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagai, S., T. Yagihashi, and A. Ishihama. 1998. An avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain produces a hemolysin, the expression of which is dependent on cyclic AMP receptor protein gene function. Vet. Microbiol. 60:227-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nataro, J. P., and J. B. Kaper. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:142-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okeke, I. N., J. A. Borneman, S. Shin, J. L. Mellies, L. E. Quinn, and J. B. Kaper. 2001. Comparative sequence analysis of the plasmid-encoded regulator of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Infect. Immun. 69:5553-5564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osek, J. 2003. Detection of the enteroaggregative Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin 1 (EAST1) gene and its relationship with fimbrial and enterotoxin markers in E. coli isolates from pigs with diarrhoea. Vet. Microbiol. 91:65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palaniappan, R. U., Y. Zhang, D. Chiu, A. Torres, C. Debroy, T. S. Whittam, and Y. F. Chang. 2006. Differentiation of Escherichia coli pathotypes by oligonucleotide spotted array. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1495-1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perna, N. T., G. Plunkett III, V. Burland, B. Mau, J. D. Glasner, D. J. Rose, G. F. Mayhew, P. S. Evans, J. Gregor, H. A. Kirkpatrick, G. Posfai, J. Hackett, S. Klink, A. Boutin, Y. Shao, L. Miller, E. J. Grotbeck, N. W. Davis, A. Lim, E. T. Dimalanta, K. D. Potamousis, J. Apodaca, T. S. Anantharaman, J. Lin, G. Yen, D. C. Schwartz, R. A. Welch, and F. R. Blattner. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 409:529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perreten, V., L. Vorlet-Fawer, P. Slickers, R. Ehricht, P. Kuhnert, and J. Frey. 2005. Microarray-based detection of 90 antibiotic resistance genes of gram-positive bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2291-2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma, V. K. 2002. Detection and quantitation of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157, O111, and O26 in beef and bovine feces by real-time polymerase chain reaction. J. Food Prot. 65:1371-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorns, C. J., C. D. Boarer, and J. A. Morris. 1987. Production and evaluation of monoclonal antibodies directed against the K88 fimbrial adhesin produced by Escherichia coli enterotoxigenic for piglets. Res. Vet. Sci. 43:233-238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, G., C. G. Clark, and F. G. Rodgers. 2002. Detection in Escherichia coli of the genes encoding the major virulence factors, the genes defining the O157:H7 serotype, and components of the type 2 Shiga toxin family by multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3613-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welch, R. A., V. Burland, G. Plunkett III, P. Redford, P. Roesch, D. Rasko, E. L. Buckles, S. R. Liou, A. Boutin, J. Hackett, D. Stroud, G. F. Mayhew, D. J. Rose, S. Zhou, D. C. Schwartz, N. T. Perna, H. L. Mobley, M. S. Donnenberg, and F. R. Blattner. 2002. Extensive mosaic structure revealed by the complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:17020-17024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu, C., T. S. Agin, S. J. Elliott, L. A. Johnson, T. E. Thate, J. B. Kaper, and E. C. Boedeker. 2001. Complete nucleotide sequence and analysis of the locus of enterocyte effacement from rabbit diarrheagenic Escherichia coli RDEC-1. Infect. Immun. 69:2107-2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.