Abstract

The community composition of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) was analyzed in roots of Gentiana verna, Gentiana acaulis, and accompanying plant species from two species-rich Swiss alpine meadows located in the same area. The aim of the study was to elucidate the impact of host preference or host specificity on the AMF community in the roots. The roots were analyzed by nested PCR, restriction fragment length polymorphism screening, and sequencing of ribosomal DNA small-subunit and internal transcribed spacer regions. The AMF sequences were analyzed phylogenetically and used to define monophyletic sequence types. The AMF community composition was strongly influenced by the host plant species, but compositions did not significantly differ between the two sites. Detailed analyses of the two cooccurring gentian species G. verna and G. acaulis, as well as of neighboring Trifolium spp., revealed that their AMF communities differed significantly. All three host plant taxa harbored AMF communities comprising multiple phylotypes from different fungal lineages. A frequent fungal phylotype from Glomus group B was almost exclusively found in Trifolium spp., suggesting some degree of host preference for this fungus in this habitat. In conclusion, the results indicate that within a relatively small area with similar soil and climatic conditions, the host plant species can have a major influence on the AMF communities within the roots. No evidence was found for a narrowing of the mycosymbiont spectrum in the two green gentians, in contrast to previous findings with their achlorophyllous relatives.

Arbuscular mycorrhiza is an ancient symbiosis (26) between the majority of land plants and fungi from the phylum Glomeromycota (30). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) colonize plant roots and contribute to the mineral nutrient uptake of the hosts in exchange for carbohydrates (32).

The diversity of AMF can be evaluated using microscopic analysis of spore morphology or molecular methods. The production of spores is highly dependent on environmental conditions and the physiological status and life strategy of the particular mycorrhizal fungus. Molecular methods allow the identification of the symbiotic community currently colonizing the roots of an individual plant at any given time. The majority of recent molecular studies have used AMF-specific primers for nuclearly encoded rRNA genes (rDNA). However, identification of AMF on the species or even isolate level is complicated by the heterogeneity of rDNA within glomeromycotan spores and isolates. Several authors have shown that different variants of rDNA genes coexist within single AMF spores (15, 27). Hence, a conservative approach in the evaluation of phylogenetic analyses is advisable by, e.g., defining a well-supported monophyletic sequence cluster as an AMF phylotype.

On the basis of the morphological features of their spores, only about 200 species of AMF have been described so far (http://www.lrz-muenchen.de/∼schuessler/amphylo/). This small number of species was originally thought to colonize the majority of higher plant species, and as a consequence, their host specificity or preference was thought to be very low (32). However, molecular studies of AMF field communities from the last decade (e.g., references 3, 12, and 40) revealed numerous previously unknown phylotypes. In several cases, significant differences were observed between the AMF communities inhabiting roots of different host plant species in the same habitat, mainly in grasslands (8, 10, 29, 36, 37). In contrast, an apparent lack of host specificity was reported by other authors (20, 28).

Achlorophyllous mycoheterotrophic members of the Gentianaceae were among the plants showing the strongest host specificity known so far in arbuscular mycorrhiza (2). Therefore, it was intriguing to see whether their green relatives show a similar restriction to a narrow clade of fungal symbionts. Previous studies provided evidence suggesting the possibility of a partly nonmutualistic interaction with AMF in gentians, based on the observation of a strong similarity of the mycorrhizal morphology between Gentiana spp. and mycoheterotrophic plants (14). Such morphology in a Paris-type mycorrhiza with hyphal coils and pronounced swellings but without apparent arbuscules was also observed in the Gentiana acaulis and Gentiana verna roots used in our study (not shown). Moreover, we previously found that G. verna could be colonized only with AMF from a living host plant of another species acting as the AMF donor (34). Therefore, data about the mycorrhizal specificity of gentians may provide insight into the presumed transition from a mutualistic arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis to mycoheterotrophy by identifying evolutionary trends in the mycorrhizal interactions.

In the present study, we used the set of primers designed by Redecker (24), allowing us to detect seven genera of Glomeromycota, which is the largest possible portion of taxon diversity recognized so far. The aims of this study were (i) to analyze and compare the communities of AMF in roots of two green gentian species and some of their surrounding plants sampled in the Swiss Alps and (ii) to evaluate whether green gentians would show specificity towards AMF similar to that of their achlorophyllous mycoheterotrophic relatives (2). The present study is also the first one to use molecular methods to analyze AMF communities in the European upper montane zone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Field sites.

The study sites were two species-rich meadows with approximately 80 plant species in two 25-m2 plots per site (K. Maurer, personal communication). They were situated close to the village Ramosch in the Engadin region of Switzerland in the upper montane forest zone (definition according to Körner [16]). Site 2A is at 10°23′30‴E/46°51′40‴N and 1,820 m above sea level [ASL] and site 11 is at 10°23′00‴E/46°51′30‴N and 2,010 m ASL). The timberline in this part of the Alps is around 2,200 m ASL. Both meadows are mown regularly, but neither is grazed by cattle or fertilized (18). They are situated about 600 m apart, separated by a forest, and exposed to the southeast. The altitude difference between the two sites is ca. 200 m. Site 11 is relatively steep and situated close to the forest line, with scattered ericaceous shrubs and Juniperus communis, whereas site 2A is a relatively flat meadow without interspersed shrubs. The dominant grass in both sites was Nardus stricta, and the sites shared approximately 50 other plant species; the remaining 30 species were unique to each site (K. Maurer, personal communication). At site 2A, the soil pH (H2O) was 6.6, the level of sodium acetate-extractable phosphorus was relatively low at 9 ng/g, and the total carbon content was 4.2% (wt/wt) (as determined in the laboratory of F. M. Balzer, Wetter-Amönau, Germany). Both sites were subjected to a plant diversity research project (17).

Sampling.

In May 2003, 16 soil cores with a diameter of ca. 20 cm and a depth of 15 cm were sampled in each meadow. The cores were randomly removed from areas of approximately 40 and 30 m in diameter. Each core contained one Gentiana verna or Gentiana acaulis plant and up to eight taxa of the surrounding plants. The plants were separated from each other and identified to the species level if possible, and their roots were washed carefully and blotted dry using tissue paper. Aliquots of 50 mg consisting of root pieces assembled from a single root system were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. Roots of the following plant species were used for further analyzes: Crocus albiflorus Kit., Hieracium hoppeanum Schult., Leontodon hispidus, an unidentified grass (“Poaceae sp.”), Polygala vulgaris, Ranunculus montanus, Thymus pulegioides, and Trifolium spp. Plants belonging to the genus Trifolium turned out to be difficult to identify to the species level, as they were not flowering; therefore, we decided to pool all Trifolium root samples into one category: Trifolium spp. Plant records made by Katrin Maurer (personal communication) suggest that this taxon may comprise Trifolium pratense, Trifolium montanum, Trifolium repens, and Trifolium badium, as these were the predominant Trifolium species at both field sites.

DNA extraction and PCR.

Roots were ground in liquid nitrogen using a pellet pestle within a 1.5-ml tube. DNA was extracted from roots using the DNeasy plant mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was eluted in two steps (each step used 50 μl of elution buffer). DNA extracts were diluted 1:10 or 1:100 in Tris-EDTA buffer and used as templates for the first PCR. PCR was performed by a nested procedure as described by Redecker (24) using Taq polymerase from Amersham (Basel, Switzerland) or New England Biolabs (BioConcept; Allschwil, Switzerland), 2 mM MgCl2, a 0.5 μM concentration of the primers, and a 0.13 mM concentration of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate. The first round of amplification was performed using the universal eukaryote primers NS5 and ITS4 (39). The cycling parameters were 3 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 45 s at 94°C, 50 s at 51°C, and 1 min 30 s at 72°C. The program was concluded by a final extension phase of 10 min at 72°C.

The PCR products were diluted 1:100 in Tris-EDTA buffer and used as templates in the second round. Five separate PCRs were performed using the primer pairs GLOM1310/ITS4i, LETC1677/ITS4i, ACAU1661/ITS4i, ARCH1311AB/ITS4i, and NS5/GIGA5.8R (24, 25). The PCR parameters for the second round differed from the first one only in the annealing temperature (61°C). Moreover, a “hot start” at 61°C was performed manually to prevent nonspecific amplification. In order to check the success of amplification, PCR products were run on agarose gels (2% NuSieve-1% SeaKem; Cambrex Bio Science, Rockland, ME) in Tris-acetate buffer at 120 V for 30 min.

Cloning, restriction fragment length polymorphism analyses, and sequencing.

PCR products were purified using the High Pure kit from Hoffman-La Roche (Basel, Switzerland) and cloned into a pGEM-t vector (Promega/Catalys, Wallisellen, Switzerland). Inserts were reamplified, and preferably 10 positive clones of each PCR product were digested with HinfI and MboI and run on agarose gels as described above. Restriction fragment patterns were compared to a database modified from the spreadsheet developed by Dickie et al. (7). Representative clones of new restriction types were then reamplified, purified using the High Pure kit, and sequenced in both directions. The BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (ABI, Foster City, CA) was used for labeling. Samples were run on an ABI 310 capillary sequencer.

Sequence analyses.

Sequences were aligned to previously published sequences in PAUP*4b10 (33). The glomeromycotan origin of the sequences was initially tested with BLAST (1). Separate internal transcribed spacer alignments were prepared for each of the target groups of the specific primers LETC1677, GLOM1310, ACAU1661, and ARCH1311AB. In addition, an alignment of the partial 3′ end of the 18S rDNA small subunit was compiled for the sequences amplified with GLOM1310 and ARCH1311AB (2).

Phylogenetic trees were obtained primarily by distance analysis (the neighbor-joining algorithm) with PAUP*4b10 using the Kimura two-parameter model and a gamma shape parameter of 0.5. Results were verified by performing maximum likelihood analyses based on parameters estimated with Modeltest 3.5 (22).

Definition of sequence phylotypes.

Sequence phylotypes were defined in a conservative manner as consistently separated monophyletic groups in the phylogenetic trees. Only those clades that were supported by neighbor-joining bootstrap analysis and also present in the respective maximum likelihood tree were used. In cases of GLOM A and ARCH phylotypes, the clades had to be supported by both 18S partial-subunit and internal transcribed spacer trees. We avoided splitting the lineages unless there was positive evidence for doing so. The sequence phylotypes were designated beginning with the major clade to which they belonged, followed by a numerical index (x in the following examples) identifying the type (11): GLOM A-x (Glomus group A), GLOM B-x (Glomus group B), ACAU-x (Acaulosporaceae), ARCH-x (Archaeosporaceae). Representative sequences of each sequence type were checked manually for possible chimeras, which were excluded from further analyses.

Statistical analyses.

The presence or absence of AMF phylotypes in each root sample was used to construct the sampling effort curves (with 95% confidence intervals, using the analytical formulas of Colwell et al. (6) in the program EstimateS, version 7.5 (5), and to calculate Shannon diversity indices H [H = −Σpi·ln(pi), where pi is the relative abundance of each sequence type.] for each plant species. G. verna, G. acaulis, and Trifolium spp. were represented by 9 to 13 root samples each, and thus these plant taxa were analyzed in detail. The data for the remaining host plant species were pooled, as only 1 to 3 root samples per plant species were analyzed due to technical limitations.

The influence of host plant species and field site on the number of sequence types found in the root samples was analyzed using the program NCSS (NCSS, Kaysville, UT). In order to investigate the influence of environmental factors (host plant species and field sites) on the distribution of the AMF phylotypes in the root samples, ordination analyzes were conducted in CANOCO for Windows, version 4.5 (35), using the presence/absence data for each root sample. Initial detrended correspondence analysis suggested a unimodal character of the data response to the sample origin (the lengths of gradients were >4); therefore, the canonical-correspondence analysis (CCA) was used. The variance-partitioning method with permutations in blocks defined by the covariables was used to compare the influence of host plants with that of field sites. Host plants were considered covariables when the influence of field sites was tested as a variable and vice versa. Monte Carlo permutation tests were conducted using 499 random permutations. The subsequent forward-selection procedure ranked the environmental variables according to their importance and significance for the distribution of the sequence types.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences of the clones were deposited in the EMBL database under the accession numbers AM384904 to AM384984, shown in the phylogenetic trees.

RESULTS

PCR yields and sequence types detected in the root samples.

Using our PCR approach with four nested-primer sets, 45 of the 67 extracted root samples (67%) yielded 119 PCR products (693 clones after the cloning), of which 71 (60%) could be ascribed to AMF phylotypes. Whereas all DNA extracts of Trifolium spp. yielded PCR amplicons of AMF origin, only 75% of G. verna and 42% of G. acaulis extracts did. No PCR products or only non-AMF amplicons were obtained from the remaining samples.

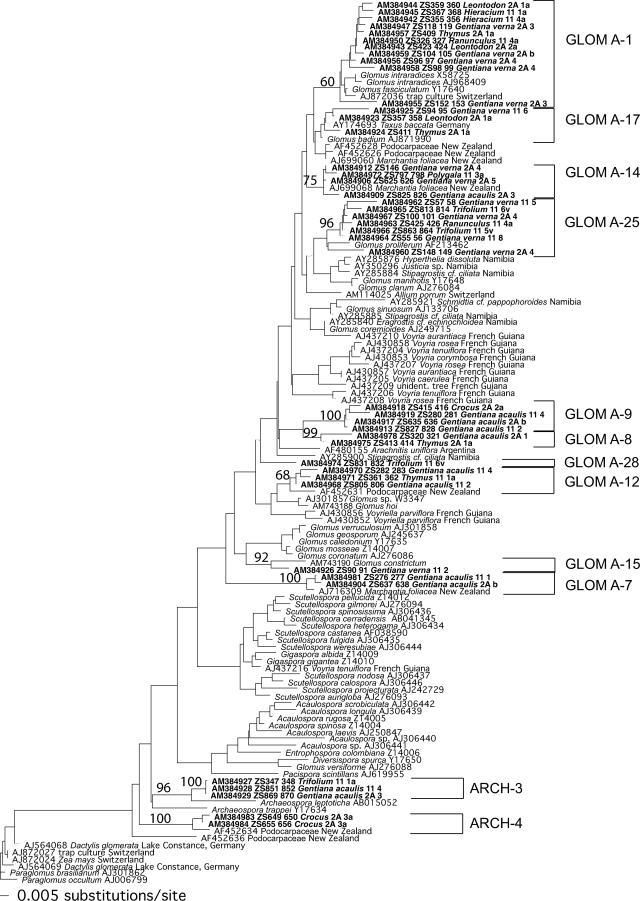

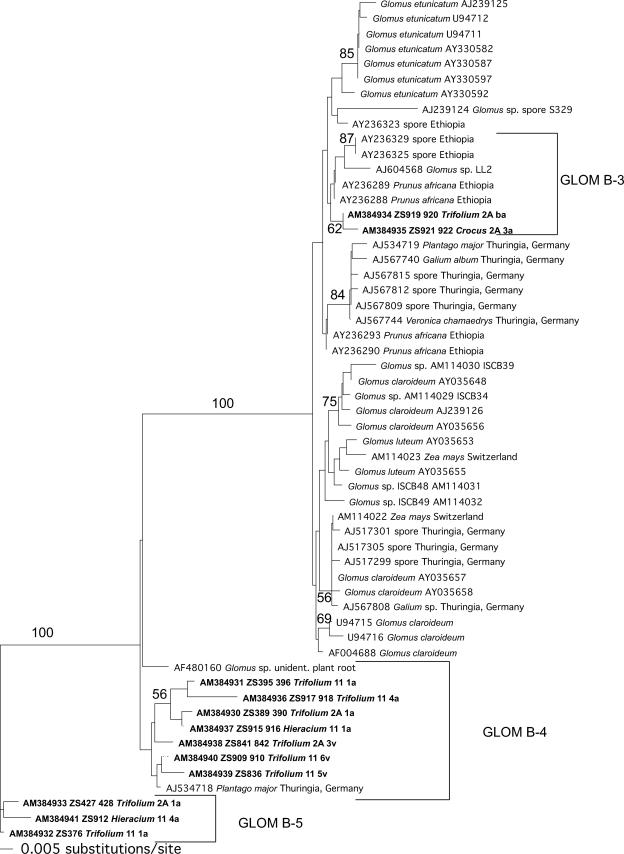

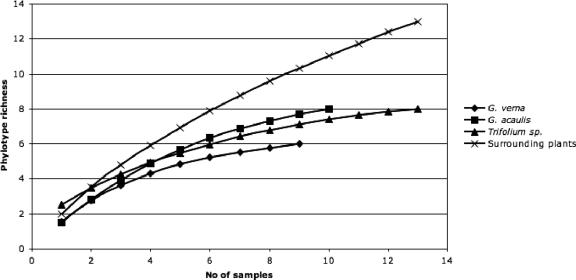

After restriction fragment length polymorphism screening, 166 clones obtained from 10 root samples of G. verna, 9 samples of G. acaulis, 13 samples of Trifolium spp., and 13 samples of other surrounding plants were sequenced and analyzed phylogenetically. All together, 17 different sequence types were found, 10 of which belonged to Glomus group A (group definitions are according to Schwarzott et al. [31]), 3 belonged to Glomus group B, 2 belonged to the Acaulosporaceae, and 2 belonged to the Archaeosporaceae (Fig. 1 and 2; see also Fig. S1, S2, and S3 and Table S1 in the supplemental material). The sampling effort curve (Fig. 3) showed that for G. verna, G. acaulis, and Trifolium spp., the number of analyzed root samples was sufficient to detect the majority of sequence types present in their roots, as the curve approaches saturation. In contrast, the curve for the pooled data of the remaining host plant species did not level off.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of Glomeromycota obtained by neighbor-joining analysis of 310 characters of the 18S rDNA subunit. Numbers above branches denote bootstrap values from 1,000 replications. The tree was rooted by Paraglomus occultum and Paraglomus brasilianum. Sequences obtained in the present study are shown in boldface. They are labeled with the database accession number (e.g., AM384944), the internal identification number (e.g., ZS359_360), the host plant species from which they were obtained (e.g., Leontodon), the field site code (2A or 11), and the soil core code (1 to 8 or A to C). Except with Gentiana verna and G. acaulis, the last letter (a or v) indicates whether the host plant was collected in a soil core with G. verna (v) or with G. acaulis (a). The brackets show the delimitation of the sequence types.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of Glomus group B based on neighbor-joining analysis of 375 characters of ITS2 and 5.8S rDNA sequences. Numbers above branches denote neighbor-joining bootstrap values from 1,000 replications. The tree was rooted using the sequence type GLOM B-5. Sequences obtained in the present study are shown in boldface and are labeled as described in the legend of Fig. 1. The brackets show the delimitation of the sequence types.

FIG. 3.

Sampling effort curve for Gentiana verna (n = 9), G. acaulis (n = 10), Trifolium spp. (n = 13), and the remaining pooled host plants (n = 13). Sample order was randomized by 100 replications in EstimateS, version 7.5 (5).

By far the most abundant sequence type (found in 29 root samples) was GLOM A-1 (Fig. 1), which corresponds to the morphologically defined species Glomus intraradices. The second- and third-most-frequent sequence types were GLOM B-4 (Fig. 2) (which could not be assigned to any morphologically described species) and GLOM A-25 (Fig. 1) (which corresponds to Glomus proliferum). Interestingly, no sequence types belonging to the genera Paraglomus, Scutellospora, or Gigaspora were found.

AMF richness and diversity.

The observed absolute numbers of sequence types per root sample were compared using analysis of variance. The host plant taxon had a significant influence (P = 0.029) on the number of sequence types, whereas the field sites did not (P = 0.60). The plant harboring the highest mean number of AMF phylotypes (2.61) was Trifolium spp., which differed significantly from G. verna and G. acaulis (1.44 and 1.50, respectively) according to Fisher's least significant difference multiple-comparison test. The mean number of AMF phylotypes harbored by the remaining host plants (2.0 [pooled data]) did not significantly differ from those of either of the host plant species mentioned above.

The Shannon diversity index calculated for different host plant species was 1.99 in the case of G. acaulis, 1.69 for Trifolium spp. (1.61 for Trifolium spp. collected in the soil cores with G. acaulis and 1.20 for Trifolium spp. collected in the soil cores with G. verna), and 1.50 for G. verna; for the remaining, pooled host plant species, it reached 2.17. The Shannon index calculated for the whole study was 2.38.

AMF communities in different host plant species and field sites.

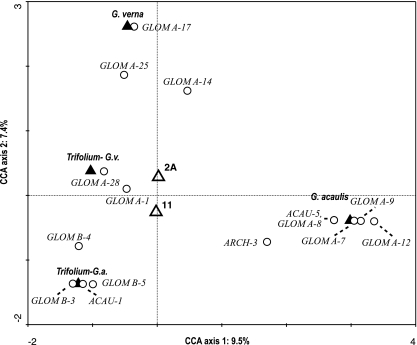

The influence of the host plant species and the field sites (subsequently called “all environmental factors”) on the distribution of AMF sequence types was investigated using a multivariate statistical approach. Sample G. verna 11-2 was excluded from the analysis as an outlier, because only one sequence type (GLOM A-15) was detected in it—which occurred only once in the whole study. CCA was focused on G. acaulis, G. verna, and Trifolium spp., as these plant taxa were represented by 9 to 13 root samples each and thus analyzed in detail. Trifolium spp. plants originating from soil cores with G. verna or G. acaulis were treated as different categories. All environmental factors explained 22.2% of the whole variance, and their effect on the distribution of AMF sequence types was clearly significant (P = 0.002). The variance partitioning showed that the host plant identity accounted for 86% of the variance explained by all environmental factors, whereas the field sites accounted only for 13.7% (the remaining 0.3% was explained by the correlation of both of them). Moreover, the influence of the host plants was statistically significant (P = 0.002). According to the forward-selection output, G. acaulis (P = 0.002) and G. verna (P = 0.004) were the two variables with significant contributions. These results demonstrate that the AMF communities hosted by those two plants were different from each other and also from the AMF harbored by Trifolium spp.

The biplot diagram of this CCA (Fig. 4) also demonstrates these results; the centroids representing the field sites are close to each other, indicating that the sites hosted similar AMF communities. In contrast, the centroids representing different host plant species are distant to each other, which demonstrates that they harbored distinct AMF. Figure 4 also clearly shows which sequence types occurred in which of these three host plants; e.g., GLOM A-7, GLOM A-8, GLOM A-9, and GLOM A-12 were hosted exclusively by G. acaulis. The only sequence type common to all three host plants was GLOM A-1, but its relative abundances differed; it was detected in 100% of Trifolium spp. samples but in only 44% of G. verna samples and 30% of G. acaulis samples (see also Table S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 4.

CCA biplot of the sequence types and environmental factors (using Hill's scaling focused on interspecies distances) of the reduced data set comprising Trifolium spp., Gentiana verna (G.v.), and G. acaulis (G.a.) samples. Host plant species are represented by filled triangles, field sites by open triangles, and sequence types by circles. The first axis accounted for 42.9% of the variability explained by all canonical axes, and differences were significant (P = 0.006). The percentages shown on the first and second axes correspond to the percentages of variance of AMF sequence type data explained by the particular axis.

The AMF communities in the roots of Trifolium spp. neighboring G. acaulis or G. verna did not significantly differ from each other. However, a trend towards more similar AMF between Trifolium spp. and its neighboring Gentiana species was observed, probably due to sharing of some phylotypes (ARCH-3 in G. acaulis and their neighboring Trifolium spp. and GLOM A-25 in G. verna and their neighboring Trifolium spp.).

The CCA conducted with the whole data set with all host plants supported the results of the first CCA: all environmental factors accounted for 33.3% of the whole variance, and their influence on the sequence type distribution was significant according to the Monte Carlo permutation test (P = 0.006). Similarly to what occurred in the first CCA, the variance partitioning method revealed that host plants accounted for 90.4% of the variability explained by all environmental factors together, whereas field sites contributed only 9.3%. The remainder (0.3%) was explained by the correlation of both of them. A CCA biplot of this analysis is shown in Fig. S4 in the supplemental material.

DISCUSSION

AMF in the European alpine and upper montane forest zones.

To our knowledge, this is the first molecular diversity study of AMF in the upper montane forest zone in Europe. Previous studies of this topic used spore morphology or root staining in order to evaluate the diversity of symbiotic fungi and root colonization (9, 23).

AMF diversity has recently been studied using the classical approach based on spore morphology in multiple field sites covering the whole Swiss Alps at altitudes from 1,000 to 3,000 m ASL (F. Oehl et al., unpublished). Part of this study was conducted in several high mountainous grazed meadows close to our study sites in the community of Ramosch and in the neighboring community Sent. Twelve to 18 AMF species were identified per site (F. Oehl, personal communication), which is in agreement with the 17 phylotypes found in our study. Oehl et al. (19) observed that species belonging to the genus Acaulospora were particularly prominent and more abundant in the Swiss Alps than in the lowlands of Switzerland; those authors also described a new species, Acaulospora alpina, which was found exclusively in the Alps at altitudes above 1,300 m ASL. As our study site near Ramosch was close to one of the study sites investigated by Oehl et al. (19), it was interesting to see whether we could recover A. alpina from colonized roots. The sequence type ACAU-5 (Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) that we detected was related to A. alpina but formed a distinct clade with sequences originating from a mountainous area from central Germany (between 640 and 705 m ASL [3]). These findings suggest the possibility of the existence of another Acaulospora clade related to A. alpina that preferentially occurs in mountainous meadows.

Relationships to phylotypes in other studies.

Fifteen out of the 17 AMF phylotypes have been found in previous studies (Table S2 in the supplemental material). Only the sequence types GLOM A-8 and GLOM B-5 were detected for the first time; i.e., no sequences belonging to these groups were found in the EMBL database. These records demonstrate a surprisingly broad ecological amplitude and geographical distribution for most of the AMF sequence types. However, due to our conservative approach in sequence type definition, it is possible that we underestimated AMF species diversity and that some sequence types contained more than one species. The molecular delimitation of an AMF species is problematic due to sequence heterogeneity within spores and species (27).

The high proportion of sequence types without a known counterpart among described morphospecies (76.5%) is consistent with previous predictions (10) that the 200 morphospecies are only a fraction of the true diversity of the Glomeromycota.

Our phylotypes cannot easily be compared to those of other studies using the primer pair NS31/AM1 because those targeted a different 18S rDNA region. In addition, Glomus group B is not detected very often using these primers, possibly because of mismatches in the annealing sites.

AMF richness and diversity at our study sites.

It is difficult to directly compare results of molecular studies of the AMF diversity in the field, as different research teams target different parts of DNA and define the sequence types inconsistently.

Nonetheless, the overall number of sequence types found in both our sites—17—is in the same range as those of other studies focusing on undisturbed plant species-rich grasslands, which revealed between 10 and 24 phylotypes (3, 21, 29, 36).

Interestingly, AMF community richness varied on two different levels, which may respond to different factors. The highest AMF richness per sample was detected in Trifolium spp. Moreover, Trifolium spp. and G. acaulis harbored a higher overall AMF richness than G. verna (see the sampling effort curves in Fig. 3). The highest overall richness was found in the category “surrounding plants,” and it was clearly not characterized exhaustively. The richness per sample, however, was not significantly different from that of G. verna or G. acaulis. These findings indicate that AMF richness in a plant taxon per root system and across the habitat may not necessarily be linked.

The lower amplification success from G. acaulis samples could have been caused by high contents of secondary metabolites, like xanthones, reported from some Gentiana species (4). A higher sampling effort was necessary to obtain a number of samples yielding PCR products comparable to those from G. verna and Trifolium spp. A lower efficiency of amplification may potentially have biased the AMF community composition detected in G. acaulis. However, this is unlikely for several reasons: (i) the sampling effort curve demonstrates that the AMF community in this plant is not less diverse than in Trifolium spp., (ii) the number of phylotypes found in each sample is not significantly different from the number in G. verna, and (iii) a systematic bias against some glomeromycotan lineages by possible differences in primer susceptibilities towards the inhibitor substances is unlikely because phylotypes were detected from the same lineages as in G. verna.

Host preference versus other factors influencing AMF communities.

The sampling effort curve (Fig. 3) shows an interesting trend: several host plant species that were pooled hosted more-different AMF sequence types than the single plant species or genus, which supports the host preference hypothesis.

Our CCA results (Fig. 4; see also Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) concerning the strong influence of the plant species on the composition of the AMF community in the roots are in agreement with the results of several studies which have presented evidence for host preferences in arbuscular mycorrhiza in the past few years (10, 36, 37). In all these cases, host plants harbored diverse communities of glomeromycotan symbionts, usually from different genera or families. In other studies, environmental factors other than host preference appeared to be dominant: site dependency (20), sampling season and soil nitrogen content (28), sampling date and field site (12), or age classes of seedlings (13).

Host specificity in the stricter sense, i.e., a host plant being colonized only by a narrow clade of fungal taxa, has been demonstrated only for mycoheterotrophic members of the Gentianaceae (2). The Gentiana species that we studied clearly show host preference but not host specificity as defined above. In this respect, they are more similar to other green plants from other families than to their mycoheterotrophic relatives. Thus, we did not find evidence for narrowing of a restricted set of symbionts as a possible symptom of a transition to a nonmutualistic symbiosis.

From the fungal point of view, our data indicate that AMF taxa belonging to Glomus group B seem to show strong preference for Trifolium spp. roots. However, none of these phylotypes was detected in Trifolium repens and Trifolium pratense in the surroundings of Jena, Germany (Stefan Hempel, personal communication). These findings are in agreement with the fact that none of the studies addressing the topic of host preferences in AMF so far has shown host preference to act across different geographical regions. Therefore, the term “local host preference” may be more appropriate to describe this phenomenon.

Ecological consequences of AMF host preference.

Scheublin et al. (29) suggested that host plant species may have various degrees of specificity for AMF species that range from selective specialists to nonselective generalists. None of the plants in our experiment showed a distinctly narrowed spectrum of fungal symbionts comparable to that of mycoheterotrophic Gentianaceae; nevertheless, the plant taxa analyzed differed in their levels of AMF richness and diversity and contained distinct communities.

Börstler et al. (3) and Öpik et al. (21) proposed the concept that some AMF species occur globally, showing high local abundance and low host specificity. Glomus intraradices clearly falls into this category as a generalist, because it has been found in a surprisingly broad range of environments. The fact that GLOM A-1 was the only sequence type in our study shared by both gentian species and Trifolium spp. strongly supports this notion. However, the second-most-frequent phylotype (GLOM B-4) showed strong evidence of host preference for Trifolium spp. The fact that this phylotype was not found in another study analyzing Trifolium spp. suggests that the local availability of a fungal inoculum and other environmental factors may also have an influence on this interaction.

The findings of van der Heijden et al. (38) showing that AMF diversity is correlated with diversity and yield of emerging plant communities suggest some degree of specificity in the interactions between symbionts in AM. This specificity can be due to preferential colonization or to specific functional interactions (e.g., nutrient transfer). Only the former aspect was addressed in this study and in other molecular studies of host preferences reported so far. The extent to which this phenomenon is responsible for the maintenance and coexistence of plant species remains to be shown in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Appoloni, S. Agten, and T. Gross for conducting some lab work; I. Hijri, P. Raab, K. Ineichen, and F. Oehl for practical advice; I. Jansová and T. Wohlgemuth for advice with multivariate analyses; K. Maurer for providing plant records from Ramosch; S. Hempel for sharing his data on AMF occurrence in Trifolium spp.; and S. Appoloni and B. Börstler for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was funded by two grants of the Swiss National Science Foundation (D.R.) and was also supported in part by the Swiss National Priority Research Programme NFP48 (Landscapes and Habitats of the Alps) (A.W.) and by a scholarship given by the Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft, Basel, Switzerland, to Z.S.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 July 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. H. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bidartondo, M. I., D. Redecker, I. Hijri, A. Wiemken, T. D. Bruns, L. Domínguez, A. Sérsic, J. R. Leake, and D. J. Read. 2002. Epiparasitic plants specialized on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Nature 419:389-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Börstler, B., C. Renker, A. Kahmen, and F. Buscot. 2006. Species composition of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in two mountain meadows with differing management types and levels of plant biodiversity. Biol. Fertil. Soils 42:286-298. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chericoni, S., L. Testai, V. Calderone, G. Flamini, P. Nieri, I. Morelli, and E. Martinotti. 2003. The xanthones gentiacaulein and gentiakochianin are responsible for the vasodilator action of the roots of Gentiana kochiana. Planta Med. 69:770-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colwell, R. K. 2005. EstimateS: statistical estimation of species richness and shared species from samples, version 7.5. http://www.purl.oclc.org/estimates.

- 6.Colwell, R. K., C. X. Mao, and J. Chang. 2004. Interpolating, extrapolating, and comparing incidence-based species accumulation curves. Ecology 85:2717-2727. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickie, I. A., P. G. Avis, D. J. McLaughlin, and P. B. Reich. 2003. Good-Enough RFLP Matcher (GERM) program. Mycorrhiza 13:171-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gollotte, A., D. van Tuinen, and D. Atkinson. 2004. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonising roots of the grass species Agrostis capillaris and Lolium perenne in a field experiment. Mycorrhiza 14:111-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haselwandter, K. 1987. Mycorrhizal infection and its possible ecological significance in climatically and nutritionally stressed alpine plant-communities. Angew. Bot. 61:107-114. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helgason, T., J. W. Merryweather, J. Denison, P. Wilson, J. P. W. Young, and A. H. Fitter. 2002. Selectivity and functional diversity in arbuscular mycorrhizas of co-occurring fungi and plants from a temperate deciduous woodland. J. Ecol. 90:371-384. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hijri, I., Z. Sýkorová, F. Oehl, K. Ineichen, P. Mäder, A. Wiemken, and D. Redecker. 2006. Communities of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in arable soils are not necessarily low in diversity. Mol. Ecol. 15:2277-2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husband, R., E. A. Herre, S. L. Turner, R. Gallery, and J. P. W. Young. 2002. Molecular diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and patterns of host association over time and space in a tropical forest. Mol. Ecol. 11:2669-2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Husband, R., E. A. Herre, and J. P. W. Young. 2002. Temporal variation in the arbuscular mycorrhizal communities colonising seedlings in a tropical forest. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 42:131-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imhof, S. 1999. Root morphology, anatomy and mycotrophy of the achlorophyllous Voyria aphylla (Jacq.) Pers. (Gentianaceae). Mycorrhiza 9:33-39. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jansa, J., A. Mozafar, S. Banke, B. A. McDonald, and E. Frossard. 2002. Intra- and intersporal diversity of ITS rDNA sequences in Glomus intraradices assessed by cloning and sequencing, and by SSCP analysis. Mycol. Res. 106:670-681. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Körner, C. 2003. Alpine plant life, 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 17.Maurer, K. 2006. Natural and anthropogenic determinants of biodiversity of grasslands in the Swiss Alps. Ph.D. thesis. University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland.

- 18.Maurer, K., A. Weyand, M. Fischer, and J. Stöcklin. 2006. Old cultural traditions, in addition to land use and topography, are shaping plant diversity of grasslands in the Alps. Biol. Conserv. 130:438-446. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oehl, F., Z. Sýkorová, D. Redecker, A. Wiemken, and E. Sieverding. 2006. Acaulospora alpina, a new arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal species characteristic for high mountainous and alpine regions of the Swiss Alps. Mycologia 98:286-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Öpik, M., M. Moora, J. Liira, U. Koljalg, M. Zobel, and R. Sen. 2003. Divergent arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities colonize roots of Pulsatilla spp. in boreal Scots pine forest and grassland soils. New Phytol. 160:581-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Öpik, M., M. Moora, J. Liira, and M. Zobel. 2006. Composition of root-colonizing arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in different ecosystems around the globe. J. Ecol. 94:778-790. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Posada, D. 2004. Modeltest 3.5. Facultad de Biologia, Universidad de Vigo, Vigo, Spain.

- 23.Read, D. J., and K. Haselwandter. 1981. Observations on the mycorrhizal status of some alpine plant-communities. New Phytol. 88:341-352. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Redecker, D. 2000. Specific PCR primers to identify arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi within colonized roots. Mycorrhiza 10:73-80. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redecker, D., I. Hijri, and A. Wiemken. 2003. Molecular identification of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in roots: perspectives and problems. Folia Geobot. 38:113-124. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redecker, D., R. Kodner, and L. E. Graham. 2000. Glomalean fungi from the Ordovician. Science 289:1920-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanders, I. R., M. Alt, K. Groppe, T. Boller, and A. Wiemken. 1995. Identification of ribosomal DNA polymorphisms among and within spores of the Glomales—application to studies on the genetic diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities. New Phytol. 130:419-427. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos, J. C., R. D. Finlay, and A. Tehler. 2006. Molecular analysis of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonising a semi-natural grassland along a fertilisation gradient. New Phytol. 172:159-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheublin, T. R., K. P. Ridgway, J. P. W. Young, and M. G. A. van der Heijden. 2004. Nonlegumes, legumes, and root nodules harbor different arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:6240-6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schüßler, A., D. Schwarzott, and C. Walker. 2001. A new fungal phylum, the Glomeromycota: phylogeny and evolution. Mycol. Res. 105:1413-1421. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwarzott, D., C. Walker, and A. Schüßler. 2001. Glomus, the largest genus of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomales), is nonmonophyletic. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 21:190-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith, S. E., and D. J. Read. 1997. Mycorrhizal symbiosis, 2nd ed. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 33.Swofford, D. L. 2001. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods). Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- 34.Sýkorová, Z., J. Rydlová, and M. Vosátka. 2003. Establishment of mycorrhizal symbiosis in Gentiana verna. Folia Geobot. 38:177-189. [Google Scholar]

- 35.ter Braak, C. F. J., and P. Smilauer. 2004. CANOCO reference manual and CanoDraw for Windows user's guide: software for canonical community ordination (version 4.5). Biometris, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- 36.Vandenkoornhuyse, P., R. Husband, T. J. Daniell, I. J. Watson, J. M. Duck, A. H. Fitter, and J. P. W. Young. 2002. Arbuscular mycorrhizal community composition associated with two plant species in a grassland ecosystem. Mol. Ecol. 11:1555-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vandenkoornhuyse, P., K. P. Ridgway, I. J. Watson, A. H. Fitter, and J. P. W. Young. 2003. Co-existing grass species have distinctive arbuscular mycorrhizal communities. Mol. Ecol. 12:3085-3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Heijden, M. G. A., J. N. Klironomos, M. Ursic, P. Moutoglis, R. Streitwolf-Engel, T. Boller, A. Wiemken, and I. R. Sanders. 1998. Mycorrhizal fungal diversity determines plant biodiversity, ecosystem variability and productivity. Nature 396:69-72. [Google Scholar]

- 39.White, T. J., T. Bruns, S. Lee, and J. Taylor. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics, p. 315-322. In M. A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, J. J. Sninsky, and T. J. White (ed.), PCR protocols, a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 40.Wubet, T., M. Weiss, I. Kottke, D. Teketay, and F. Oberwinkler. 2004. Molecular diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in Prunus africana, an endangered medicinal tree species in dry Afromontane forests of Ethiopia. New Phytol. 161:517-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.