Abstract

In the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta, proteolytic activation of prophenoloxidase (proPO) is mediated by three proPO-activating proteinases (PAPs) and two serine proteinase homologs (SPHs) (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 95 (1998) 12220–12225; J. Biol. Chem. 278 (2003a) 3552–3561; Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 33 (2003b) 1049–1060). While our current data are consistent with the hypothesis that the SPHs serve as a cofactor/anchor for PAPs (Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 33 (2003) 197–208; Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 34 (2004) 731–742), roles of these clip-domain proteins (i.e. PAPs and SPHs) in proPO activation are poorly defined. To better understand this process, we further characterized the activation reaction using proPO, PAP-1 and SPHs. PAP-1 itself cleaved nearly 1/3 of proPO at Arg51 without generating much phenoloxidase (PO) activity. In the presence of SPHs, the cleavage of proPO became more complete while the increase in PO activity was over 20-fold, indicating that the extent of cleavage does not directly correlate with PO activity. Since SPHs and p-amidinophenyl methanesulfonyl fluoride (APMSF)-treated PAP-1 did not generate active PO by interacting with proPO, proteolytic cleavage is critical for proPO activation. After 1/5 of proPO was processed by PAP-1 alone which was then inactivated by M. sexta serpin-1J or APMSF, further incubation of the reaction mixture with SPHs failed to generate active PO either. Thus, SPHs cannot generate PO activity by simply binding to cleaved proPO. M. sexta proPO activation requires active PAP-1 and SPHs at the same time—one for limited proteolysis and the other as a cofactor, perhaps. Gel filtration chromatography and native gel electrophoresis revealed the PAP-SPH, proPO-PAP, and SPH-proPO associations, essential for generating high Mr, active PO at the site of infection.

Keywords: Phenoloxidase, Malanization, Serine proteinase, Clip domain, Insect immunity, Hemolymph proteins, Tobacco hornworm

1. Introduction

Proteolytic activation of prophenoloxidase (proPO) in insects and crustaceans is an important physiological process against pathogen infection (Ashida and Brey, 1998; Söderhäll and Cerenius, 1998). It generates PO that catalyzes the formation of quinones. Quinones are reactive intermediates for cuticle sclerotization and melanin synthesis. They may also participate in wound healing and pathogen killing/sequestration. To minimize possible cytotoxicity of quinones to host tissues and cells, proPO activation and PO activity need to be regulated as a local reaction against invading microorganisms. Several controlling mechanisms have already been elucidated, including recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns, activation of proPO by a cascade of interacting proteinases, inhibition of proPO-activating proteinases (PAPs) by serpins, and requirement of clip-domain serine proteinase homologs (SPHs) for generating active PO. Among them, the function of SPHs appears to be most intriguing and somewhat controversial at present (Jiang et al., 1998, 2003a, b; Lee et al., 1998; Satoh et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2003; Wang and Jiang, 2004).

M. sexta SPH-1 and SPH-2 are similar in sequence to clip-domain serine proteinases (e.g. PAPs) but lack a proteolytic activity, because their active site Ser is replaced by a Gly residue. They associate with immulectin-2, a C-type lectin that binds lipopolysac-charide and mannan (Yu and Kanost, 2000). Through interactions with PAP and proPO, these proteinase-like molecules may anchor proPO activation to the surface of microorganisms. A masquerade-like, clip-domain SPH from the crayfish Pacifastacus leniusculus may serve as an opsonin by associating with microbial cells and host hemocytes (Huang et al., 2000; Lee and Söderhäll, 2001). We have isolated three clip-domain serine proteinases from M. sexta, which cleave proPO at Arg51 but require the SPHs to generate active PO. To distinguish them from Bombyx mori proPO-activating enzyme (PPAE) which yielded active PO by itself (Satoh et al., 1999), we named the M. sexta enzymes PAP-1, PAP-2, and PAP-3 and proposed that M. sexta PPAE could be a PAP-SPH complex and that SPHs may serve as a cofactor for PAP (Wang and Jiang, 2004). While our results agree with these hypotheses, a detailed mechanism is still unknown for the clip-domain SPHs. Consequently, we consider “PAP cofactor” as a tentative term and use it interchangeably with M. sexta SPH-1 and SPH-2 in this paper.

The requirement of proteins other than PAPs for proPO activation was also observed in Hyalophora cecropia, Holotrichia diomphalia, and Tenebrio molitor (Andersson et al., 1989; Lee et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2002). H. diomphalia proPO-activating factor I (PPAF-I) cleaved proPO polypeptide-1 and -2 at Arg50 and Arg51, respectively, but generated little PO activity. In the presence of cleaved H. diomphalia PPAF-II (a clip-domain SPH), the proPO polypeptide-1 was further cleaved by PPAF-I at Arg160 to produce active PO. The precursor of PPAF-II is activated by another clip-domain serine proteinase, H. diomphalia PPAF-III (Kim et al., 2002).

With three PAPs and two SPHs involved, proPO activation in M. sexta appears to be more complex than those in the other insect systems. To understand the auxiliary effect of SPH-1 and SPH-2, we investigated the molecular associations among proPO, PAP-3, and SPHs (Wang and Jiang, 2004). HPLC gel filtration chromatography coupled with proPO activation assays allowed the detection of all three binary complexes. We also found that the association between PAP-3 and proPO was stronger than the proPO-SPH or SPH-PAP association. However, it is unclear if similar protein-protein interactions exist among proPO, SPHs, and PAP-1/PAP-2 and if such interactions are essential for proPO activation. In this work, we found that proteo-lytic cleavage is critical for proPO activation but not directly correlated with PO activity. ProPO, PAP-1, and SPHs have to be present at the same time to generate active PO, which represents a previously unknown mechanism for regulating the proPO activation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Purification of M. sexta proPO, PAP-1, SPHs, and serpin-1J

M. sexta proPO was isolated from the larval hemolymph as described before (Jiang et al., 1997). PAP-1 and SPHs were prepared from cuticle and hemolymph of the prepupae, respectively (Wang and Jiang, 2004; Gupta et al., 2004). M. sexta serpin-1J was expressed as a soluble protein in Escherichia coli (Jiang and Kanost, 1997). The recombinant serpin was purified by ammonium sulfate fractionation, Ni-affinity chromatography, and ion exchange chromatography (Jiang et al., 2003b).

2.2. PO and PAP-1 activity assays

PO activity was determined by a microplate assay using dopamine as a substrate (Jiang et al., 2003a). The amidase activity of PAP-1 was measured similarly using acetyl-Ile-Glu-Ala-Arg-p-nitroanilide (IEARpNA) as a chromogenic substrate (Jiang et al., 2003a).

2.3. SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis of proPO cleavage

For SDS-PAGE analysis, protein samples were treated with SDS sample buffer containing 0.1 M dithiothreitol and separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Laemmli, 1970). Proteins were visualized by silver staining or immunoblot analysis using 1:2000 diluted rabbit antiserum to proPO (Jiang et al., 1997).

2.4. Inspection of the relationship between proPO cleavage and PO activity

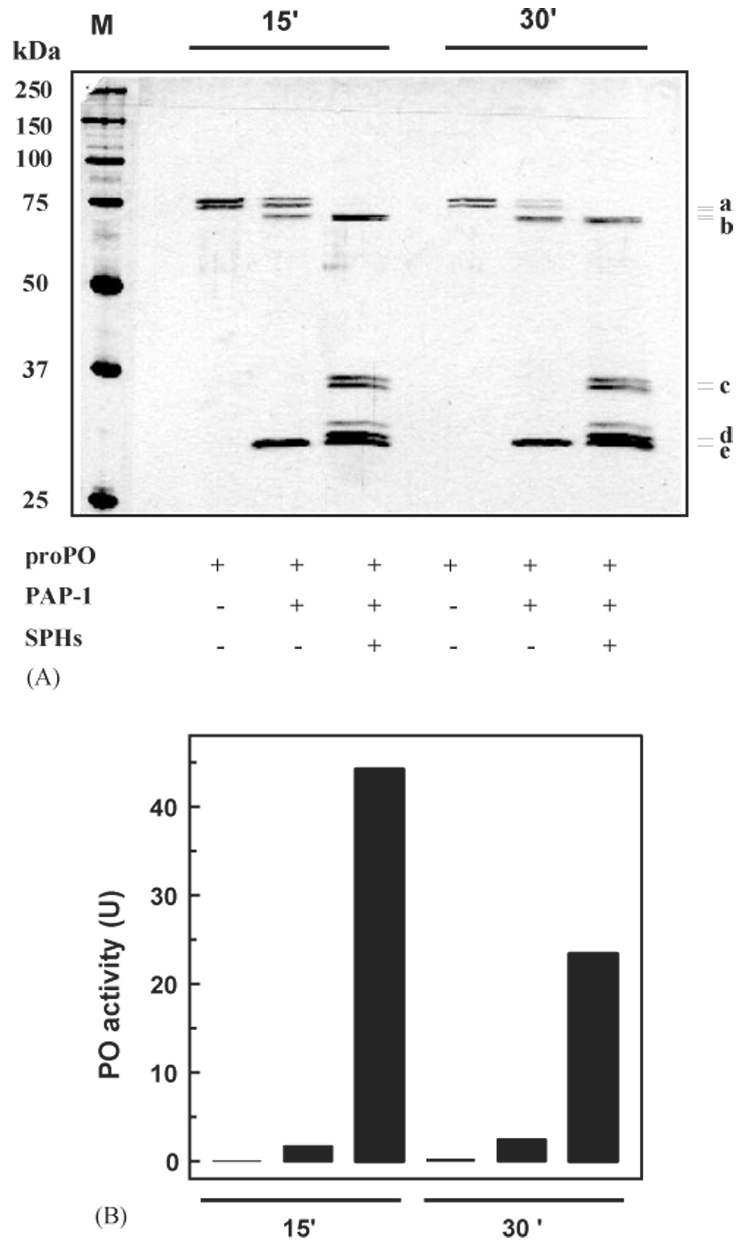

To test if there is a direct correlation between proPO cleavage and PO activity, proPO was incubated with buffer, PAP-1, or a mixture of PAP-1 and SPHs at room temperature for 15 or 30 min (see Fig. 1 legend for details). The reaction mixtures were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE and silver staining to reveal the cleavage extent of proPO. In the duplicate reactions, PO activities were measured and compared with the relative amounts of cleaved proPO.

Fig. 1.

Examination of the relationship between proPO cleavage and PO activity. As described in Section 2, proPO (10 µl, 10 ng/µl) was incubated with buffer (6 µl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0), buffer and PAP-1 (4 µl + 2 µl, 20 ng/µl), or a mixture of buffer, PAP-1 and SPHs (2 µl + 2 µl, 20 ng/µl + 2 µl, 20 ng/µl) at room temperature for 15 or 30 min. The reaction mixtures (containing 0.001% PTU) and molecular weight standards (lane M) were treated with SDS-sample buffer, separated on 10% gel under reducing condition, and visualized by silver staining (A). Correlating with the lanes in panel A, PO activities (in the duplicate reactions not containing PTU) were measured and plotted in the bar graph (B). Position and size of the protein standards are indicated in panel A. (a) proPO polypeptide-1 and -2; (b) cleaved proPO polypeptide-1 and -2; (c) 37 kDa cleaved SPH-1 and SPH-2; (d) 30 kDa cleaved SPH-1; (e) PAP-1 catalytic domain. The identities of these bands were confirmed by immunoblot analysis (data not shown).

2.5. Examination of the significance of limited proteolysis on proPO activation

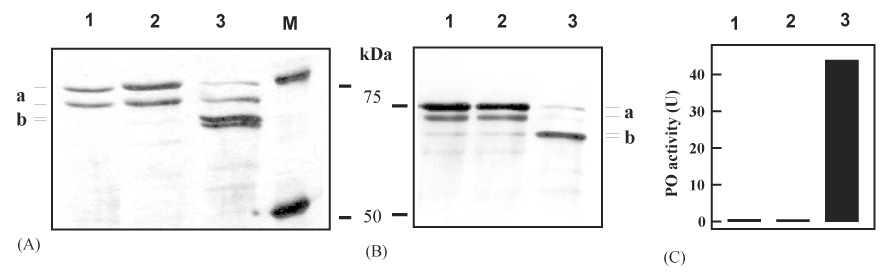

For assessing the role of proteolysis in proPO activation, proPO and SPHs were incubated with buffer, APMSF-inactivated PAP-1, or active PAP-1 at 0 °C for 1 h (see Fig. 2 legend for details). The reaction mixtures were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining or immunoblot using proPO antibodies. The extent of proPO cleavage was examined and compared with corresponding PO activities in the duplicate reactions.

Fig. 2.

The importance of limited proteolysis in proPO activation. After PAP-1 (2 µl, 20 ng/µl) was inactivated by freshly prepared APMSF (2 µl, 8 mM in H2O) at 0 °C for 10 min, proPO (10 µl, 10 ng/µl) and SPHs (2 µl, 20 ng/µl) were added and incubated for 50 min. The controls are proPO only and a mixture of proPO, PAP-1 (active), and SPHs incubated at 0 °C for 60 min. Following SDS-PAGE under reducing condition, the proteins were visualized by silver staining (A) or immunoblot analysis using 1:2000 diluted proPO antiserum as the first antibody (B). PO activities in the duplicate reactions were measured and plotted in the bar graph (C). The polyacrylamide gels were 6% for (A) and 10% for (B). Size and position of the protein standards are marked. Lane 1, proPO; lane 2, proPO + APMSF-treated PAP-1 + SPHs; lane 3, proPO + active PAP-1 + SPHs. (a) proPO polypeptide-1 and -2; (b) PO polypeptide-1 and -2.

2.6. Possible activation of cleaved proPO by SPHs

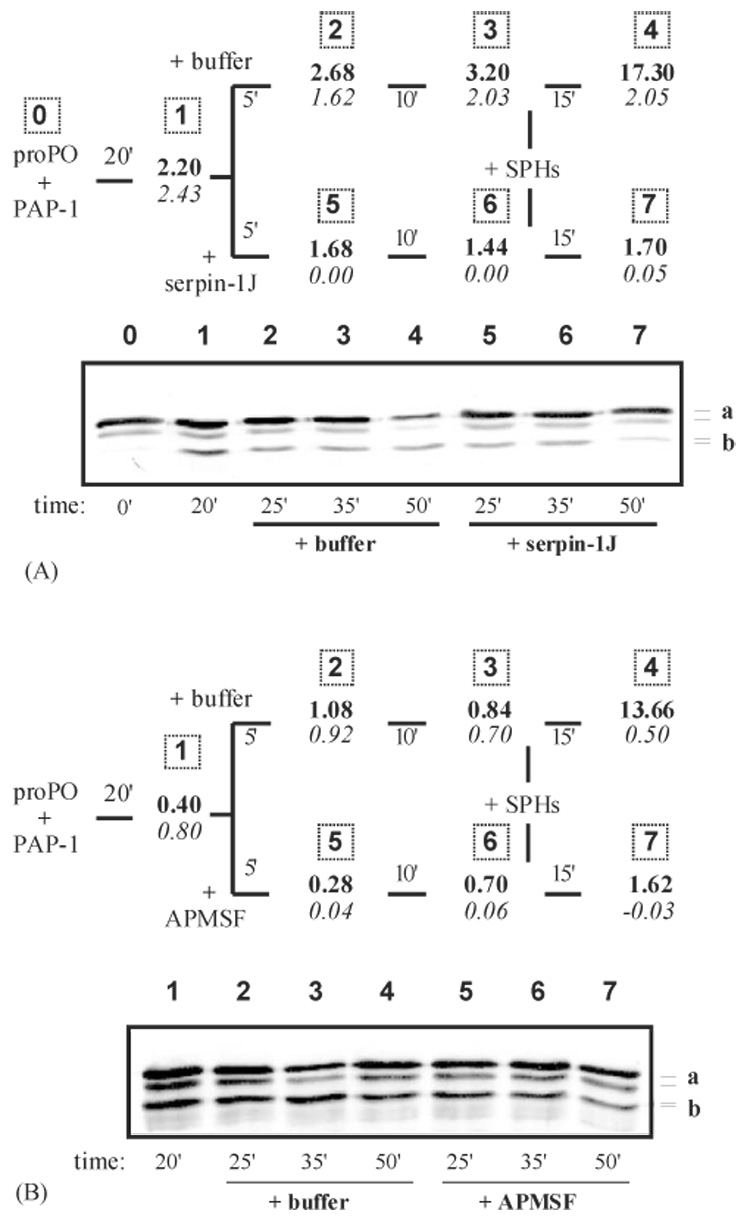

To test if SPHs can bind to cleaved proPO and yield PO activity in the absence of active PAP-1, proPO and PAP-1 were first incubated on ice for 20 min (see Fig. 3 for details). Aliquots of the reaction mixtures were taken for PO activity assay, PAP amidase assay, and immunoblot analysis using proPO antibodies. Recombinant serpin-1J was added to inactivate the proteinase in half of the reaction mixture whereas buffer was added to the other half as a control. Samples were taken after 5 and 15 min for the activity assays and immunoblot analysis. SPHs were added to the two mixtures, incubated at 0 °C for 15 min, and subjected to the activity and gel analyses. The same experiment was carried out using APMSF instead of serpin-1J to inactivate PAP-1.

Fig. 3.

The effect of SPHs on cleaved proPO in the presence of serpin-1J- or APMSF-inactivated PAP-1. (A) After proPO (30 µl, 10 ng/µl), PAP-1 (3.0 µl, 20 ng/µl), and buffer (12 µl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) were incubated on ice for 20 min, recombinant serpin-1J (6.0 µl, 0.5 µg/µl) was added to inactivate the proteinase. The buffer (6.0 µl), instead of serpin-1J, was added to a duplicate reaction as a control. Samples (5 µl) were taken before (20′), 5 min after (25′) and 10 min after (35′) serpin-1J or buffer was thoroughly mixed. Then, SPHs (3.0 µl, 20 ng/µl) were added to the reaction mixtures and further incubated for 15 min at 0 °C. All the samples were subjected to PO and amidase activity assays (upper panel) and 6% SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis using proPO antibodies (lower panel). (B) The same as (A), except that APMSF (8 mM) was used instead of serpin-1J. In the upper panels, PO activity at each time point was shown in bold whereas IEARase activity in italic. In the lower panels, lane numbers correspond to the sampling numbers (upper panels). (a) proPO polypeptide-1 and -2; (b) cleaved proPO polypeptide-1 and -2.

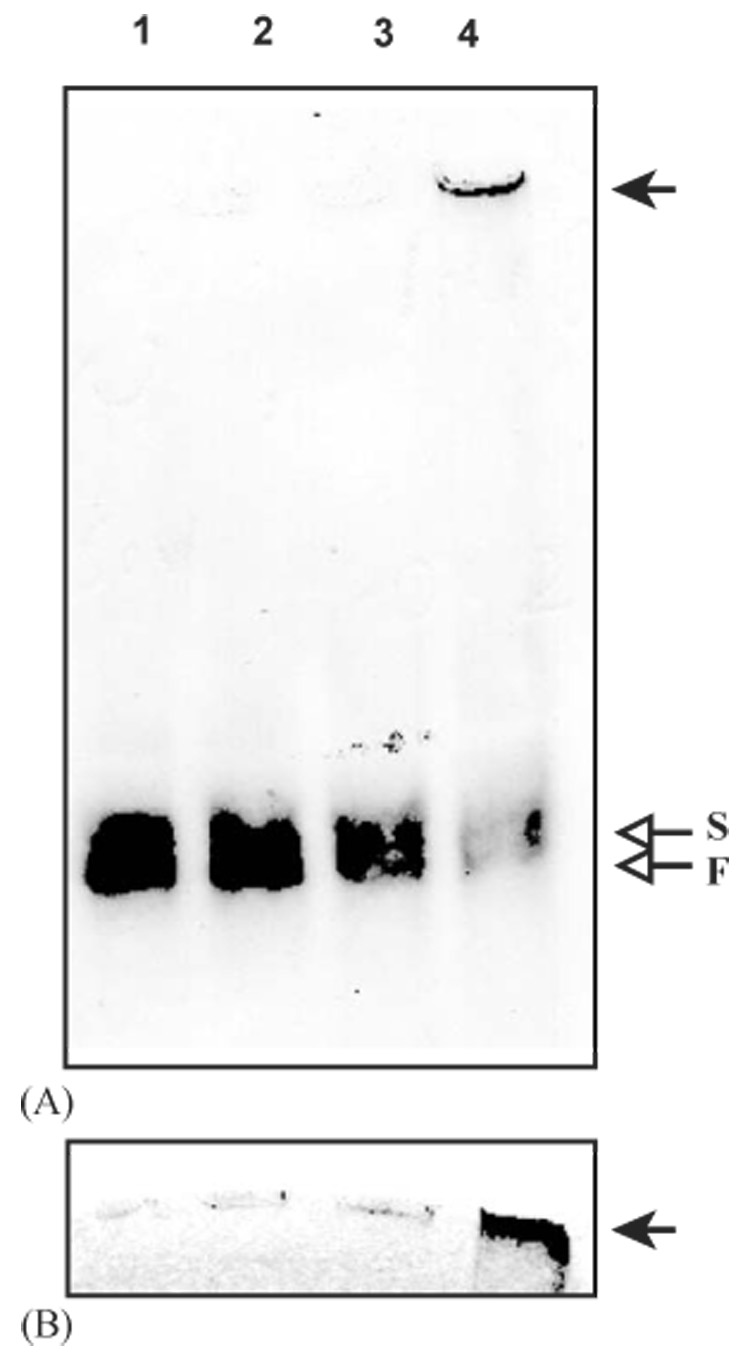

2.7. Electrophoretic analysis of cleaved proPO on native gel

Purified proPO was incubated with buffer, PAP-1, SPHs, or a mixture of PAP-1 and SPHs on ice for 60 min (see Fig. 4 for details). The reaction mixtures were individually mixed with sample buffer without SDS or reducing agent (Laemmli, 1970) and separated on 6% polyacrylamide gel under non-denaturing conditions (4 °C, constant current, 12 mA/gel). After electrophoresis, the stacking and separating gels together were incubated with 2 mM dopamine in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) to detect PO activity. The same protein samples on a duplicate gel were treated with 1% SDS for 15 min, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and analyzed using proPO antibodies.

Fig. 4.

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic analysis of cleaved proPO. As described in Section 2, proPO (0.5µg/µl, 1 µl) was incubated with buffer (lane 1, 9µl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0), PAP-1 (lane 2, 1 µl, 20 ng/µl and 8µl buffer), SPHs (lane 3, 1 1 #x000B5;l, 20 ng/µl and 8µl buffer), or a mixture of PAP-1 and SPHs (lane 4, 20 ng each and 7µl buffer) on ice for 60 min. The reaction mixtures were separated on 6% polyacrylamide gel under non-denaturing condition, and detected by proPO antibodies (A) or in-gel PO activity assay (B). The PO activity recognized by the antibodies (arrow) is located at the top of the stacking gel. On native gels, proPO mostly migrates as heterodimers of proPO-p1 and proPO-p2 in two allelic forms (Jiang et al., 1997). Here, due to limited resolution of native gel electrophoresis, the proPO cleaved by PAP-1 alone (lane 2) appears to co-migrate with the zymogen in the slow (S) and fast (F) migrating forms.

2.8. Association of proPO, PAP-1, and SPHs

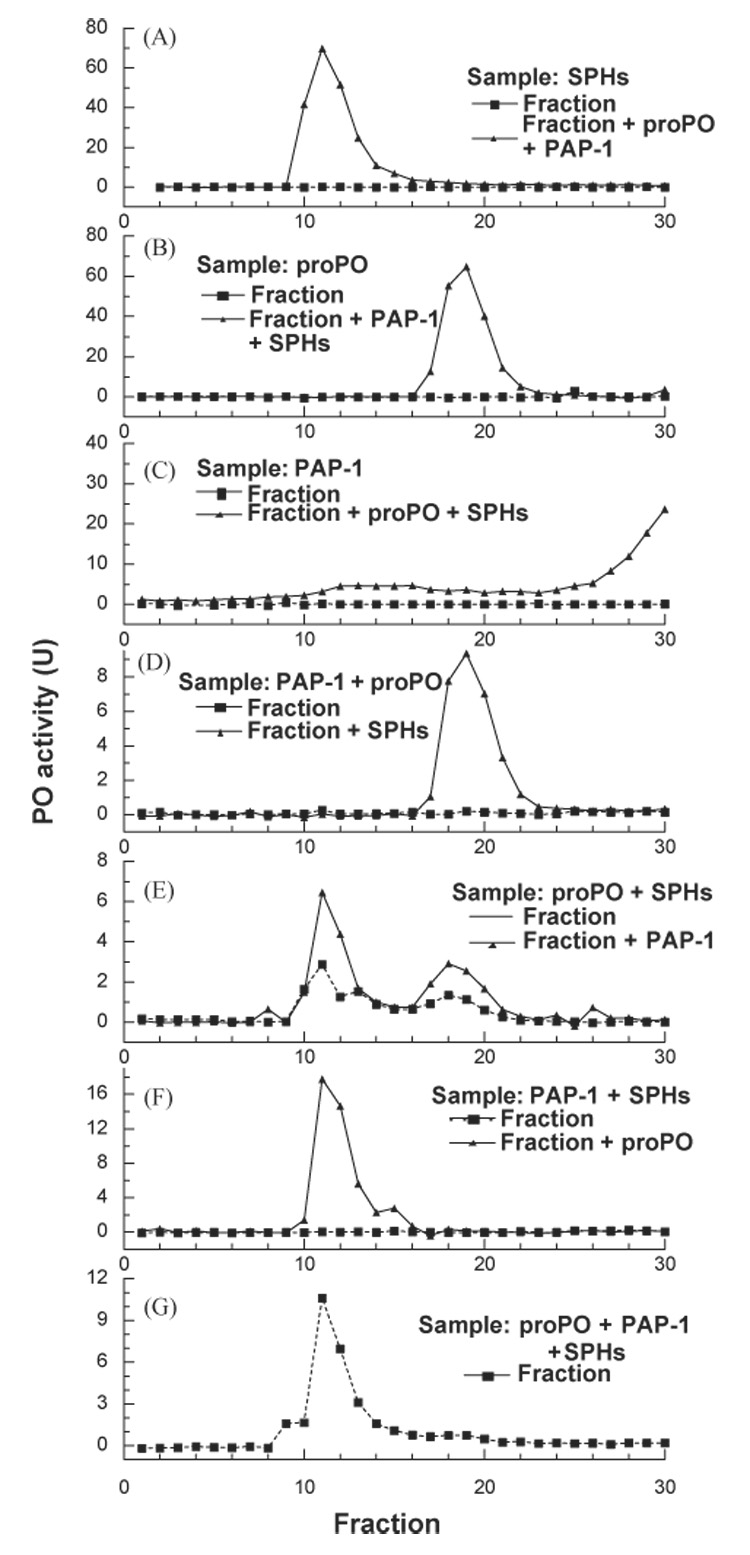

Purified proPO, PAP-1, and its cofactor were first individually analyzed by size exclusion chromatography on an HPLC gel filtration column equilibrated with 0.1 M potassium phosphate, 20 mM KCl, pH 7.5 (Wang and Jiang, 2004). The proteins were eluted by the same buffer at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min and fractions were collected at 0.33 ml/tube. The other two reaction components were incubated with each elution fraction (50 µl) on ice for 1 h, and PO activity was determined to locate the loaded protein and its elution time. Secondly, any two of these three components were mixed and resolved on the column. The third component was then incubated with the fractions individually to detect any complex formation. At last, proPO, PAP-1, and SPHs were mixed and immediately injected into the separation system. After 1 h at 0 °C, PO activity in the column fractions was measured to reveal the ternary complex formation.

3. Results

3.1. Relationship between proPO cleavage and PO activity

In a previous paper (Yu et al., 2003), we reported that PAP-1 alone cleaved a little proPO. In the presence of SPHs (which did not cleave proPO), the proteolysis became more complete (~30%) and a high level of PO activity (22 U) was generated. When purified PAP-1 was available (Gupta et al., 2004), we repeated the same experiment to test whether the extent of cleavage has any direct correlation with PO activity. To our surprise, when nearly 1/3 of proPO had been cleaved by PAP-1 alone at room temperature for 15 min, we detected low PO activity (1.7 U) (Fig. 1). Complete proteolysis was achieved in the presence of SPHs and, while cleavage efficiency increased nearly 3-fold, we detected a 25-fold increase in PO activity (44 U). At 30 min after PAP-1 was incubated with proPO, ~2/3 of the substrate was converted in the absence of cofactor, and we again detected a low PO activity (2.4 U). When the SPHs were present in the reaction mixture, we observed 1.5- and 9.6-fold increases in cleavage extent and PO activity, respectively. Again, there is no direct correlation between cleaved proPO and PO activity, and the SPHs are critical for producing active PO.

3.2. Significance of proteolytic cleavage in proPO activation

While a linear relationship does not exist between cleavage extent and PO activity, is the limited proteolysis of proPO important at all for generating active PO? Perhaps, like other organic chemicals (e.g. detergents and alcohols) or polypeptides (e.g. antimicrobial peptides, serine proteinase precursors) (Asada et al., 1993; Decker et al., 2001; Nagai et al., 2001; Nagai and Kawabata, 2000), PAP-1 and SPHs could simply bind to proPO, change its conformation, and yield PO activity without any proteolysis. To test this possibility, we first incubated PAP-1 with an irreversible serine proteinase inhibitor, APMSF, to block its amidase activity. We then added SPHs and proPO, incubated the reaction mixture on ice for 1 h, and examined proPO processing and PO activity. As anticipated, proPO was not hydrolyzed by the inactivated PAP-1 (Fig. 2). We did not detect any active PO, either. In other words, proteolytic cleavage by PAP-1 is essential for proPO activation by PAP and SPHs.

3.3. Simultaneous requirement of PAP-1 and SPHs for proPO activation

As we started to use the term “cofactor” (Jiang et al., 1998), its identity and mechanism was not understood. Neither did we provide evidence that SPHs and PAP have to be present simultaneously—a prerequisite for SPHs to serve as “PAP cofactor”. While the increase in proPO cleavage and PO activity (Fig. 1) was certainly indicative of a direct interaction of SPHs with PAP and/or proPO (Wang and Jiang, 2004), we did not know if cleavage of proPO by PAP-1 and binding of cleaved proPO by SPHs can be two independent steps for generating PO activity. In other words, can SPHs simply bind to cleaved proPO and yield active PO, but not serve as a “cofactor” by interacting with PAP-1?

To test this possibility, we preincubated proPO with PAP-1 on ice for 20 min and detected significant cleavage (~1/5) but low PO activity (2.2 U) (Fig. 3A). The PO and PAP-1 amidase activities did not change substantially after buffer was added to half of the reaction mixture. At 5 min and 15 min after serpin-1J was added to the other half, the PAP-1 amidase activity was completely blocked whereas the PO activity did not decrease much. We then added the same amount of SPHs to both reactions and incubated them on ice for another 15 min. In the mixture containing active PAP-1, we detected a high level of PO activity (17.3 U) (Fig. 3A). In contrast, we did not detect any significant PO activity increase in the serpin-containing sample.

Although these results suggested that active PAP-1 and SPHs are needed at the same time for proPO activation, we had to exclude the possibility that the PAP-serpin complex somehow interfered with association between SPHs and cleaved proPO and abolished the process of generating active PO. Therefore, we repeated the same experiment by replacing serpin-1J with APMSF, a small irreversible serine proteinase inhibitor not expected to interfere with the protein-protein interaction. In the presence of APMSF-inactivated PAP-1, the SPHs failed to generate PO activity by binding to cleaved proPO (Fig. 3B). In contrast, we observed a marked increase in PO activity in the control reaction where active PAP-1, proPO, and SPHs were all present at the same time.

3.4. The difference between active and inactive PO

Since proPO proteolysis is indirectly correlated with PO activity (Fig. 1), cleaved proPO probably has more than one activation state—some cleavage products may be inactive. SPHs, required at the same time as PAP-1 cleaves proPO, may somehow induce and/or stabilize the formation of active PO. If this is true, what is active PO and how is it different from inactive, cleaved proPO? To answer these questions, we examined the association status of cleavage products by electrophoretic analysis on a native polyacrylamide gel. PAP-1 alone yielded cleavage products co-migrating with proPO (Fig. 4A). In comparison, as the amount of proPO was greatly reduced after PAP-1 and SPHs treatment, we detected an immunoreactive band that hardly left the sample well in the stacking gel. This band corresponded to the active PO detected by the in-gel activity assay (Fig. 4B). Due to its stickiness, some active PO was probably lost during sample preparation. No PO activity was detected at the positions of proPO or PAP-1-cleaved proPO. These results indicated that active PO has a much higher Mr than the inactive PO. The SPHs possibly determine the association state of cleaved proPO, a new function consistent with our previous hypotheses that M. sexta PPAE can be a PAP-SPH complex and that SPHs may serve as a cofactor/anchor for PAP.

3.5. Molecular interactions among proPO, PAP-1, and SPHs

HPLC gel filtration chromatography coupled with proPO activation assays indicated that SPHs and proPO peaked in fractions 11 and 19, respectively (Fig. 5, A and B). PAP-1 associated with the column and eluted mainly in fractions 30–48 as a broad peak (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Associations among M. sexta proPO, PAP-1, and SPHs. As described in Section 2, SPHs (A), proPO (B), or PAP-1 (C) was analyzed by gel filtration chromatography coupled with proPO activation assay to locate the applied proteins. To detect possible binary complexes of proPO-PAP-1 (D), proPO-SPHs (E), SPHs-PAP-1 (F), two of the three reaction components were combined and separated on the same column. Complex formation in the fractions was detected by incubating the fractions with the third component and by PO activity assay. To detect the formation of a ternary complex (G), proPO, PAP-1, and SPHs were mixed and separated by gel filtration chromatography, and PO activity in the column fractions was measured 1 h after the fractions had been collected. Injected samples, protein(s) for detection, and results from the test (▲-----▲) and control (■——■) experiments are indicated in each panel.

After proPO and PAP-1 were combined and then resolved on the same column, proPO activation was detected in fractions 18–21 in the presence of SPHs (Fig. 5D), indicative of complex formation between proPO and PAP-1. The peak shape and elution time did not differ from those of proPO (Fig. 5B)—“sticky” portions of PAP-1 were probably buried in the complex and did not interact with the column to affect the elution profile. We have also observed the association between proPO and SPHs (Fig. 5E): proPO in fractions 10–13 and 17–20 was activated by PAP-1 (added in the assay) in the presence of SPHs (in the same fractions). Since there were two peaks of proPO activation, close to the SPHs and proPO elution times (Fig. 5A and C), the proPO-SPH association seemed to be looser than the proPO-PAP association. When the mixture of PAP-1 and SPHs was separated by gel filtration, fractions 11–14 activated proPO at higher levels than the fraction controls (Fig. 5F), indicating a complex formation between PAP-1 and SPHs. The distribution of such complex was narrower than SPHs only (Fig. 5A), suggesting that “sticky” parts of PAP-1 and SPHs may participate in the protein-protein interaction. This is markedly different from the complex of PAP-3 and SPHs, which spread all over the column fractions (Wang and Jiang, 2004). Finally, after proPO, PAP-1, and SPHs were mixed and immediately resolved on the column, we detected a PO activity peak in fractions 10–14 (Fig. 5G). This result further confirmed that active PO has a high molecular weight (Fig. 4).

4. Discussion

So far, results from different insects are not consistent regarding the requirement of clip-domain SPH(s) for proPO activation and relationship between PO activity and proteolytic events. The silkworm PPAE by itself cleaved proPO after Arg51 and generates active PO (Satoh et al., 1999). The H. diomphalia PPAF-1 alone cut proPO at the corresponding site but failed to generate active PO, unless Arg162 of proPO polypeptide-1 was cleaved in the presence of a clip-domain SPH (Lee et al., 1998). In M. sexta, PAP-1, -2, and -3 cleaved proPO at Arg51 and the proteolysis was more complete after the SPHs were added (Fig. 1). Our unpublished results indicate that M. sexta proPO polypeptide-1 can also be hydrolyzed at Arg163 under certain conditions, but the significance of such cleavage is still unclear. At this moment, we cannot exclude the possibility that the high PO activity resulted from minute amounts of secondary cleavage product. Site-directed mutagenesis and recombinant expression of proPO should allow us to confirm or disprove the role of cleavage at Arg163 during proPO activation in M. sexta.

Although details are still lacking regarding the cleavage events, it is quite clear that PAP and proPO function as an enzyme-substrate pair during proPO activation. On the other hand, the “cofactor” activity of SPHs remains intriguing: SPHs do not cleave proPO (Yu et al., 2003; Wang and Jiang, 2004), but they enhance proPO cleavage by PAP-1 (Fig. 1), PAP-2 (Jiang et al., 2003a), and PAP-3 (unpublished data). It is unknown whether or not SPH-1 and SPH-2 are both needed and how they affect proPO activation. In this paper, we proved that proPO, active PAP-1, and SPHs must coexist to generate active PO. While this finding can be considered as a prerequisite for SPHs to serve as a “PAP cofactor”, it actually represent a previously unknown mechanism for regulating proPO activation. M. sexta SPH-1 and SPH-2 associated with immulectin-2, a C-type lectin that binds lipopolysaccharide and mannan, perhaps to anchor proPO activation to a pathogen surface (Yu and Kanost, 2000; Yu et al., 2003). Now, we demonstrated that proPO, after cleavage by PAP-1 at the correct site in the absence of the SPHs, has little PO activity (Fig. 1). Neither did the cleavage product become active by binding to the SPHs (Fig. 3). These ensure that, even if PAP molecules diffuse away from the site of infection, escape from irreversible proteinase inhibitors (e.g. serpins), and cleave its substrate proPO, active PO will not be generated to cause damage to the host. In other words, PO activity has to be produced locally at the site of wounding or pathogen infection.

What biochemical mechanism could be responsible for such a tight regulation? Based on the interactions observed in the gel filtration experiment, the SPHs bind to both PAP-1 and proPO (Fig. 5). These bindings, as well as the interaction between PAP-1 and proPO, ensure a more efficient proteolysis of proPO (Fig. 1) and an active conformation. In the presence of proPO, SPHs, and APMSP-inactivated PAP-1, although suitable interactions were there, no cleavage can be made to trigger a conformation change for yielding active PO (Fig. 2). In the other case, PAP alone cleaved proPO (Fig. 3) and, since SPHs were absent, the cleavage-induced conformation can be either unstable or distorted for manifesting PO activity. After SPHs were replenished later in the presence of inactivated PAP-1, the proteinase-like molecules failed to regenerate the active conformation by simply binding to cleaved proPO. This model successfully explained why there was no direct correlation between cleavage extent and PO activity level (Fig. 1).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM58634 (to H. J.). We thank Drs. Kanost and Dillwith for their helpful comments on the manuscript. This article was approved for publication by the Director of Oklahoma Agricultural Experimental Station and supported in part under project OKLO2450.

Abbreviations

- proPO and PO

prophenoloxidase and phenolox-idase

- PAP

proPO-activating proteinase

- PPAE

proPO activating enzyme

- SPH

serine proteinase homolog

- IEARpNA

acetyl-Ile-Glu-Ala-Arg-p-nitroanilide

- PTU

1-phenyl-2thiourea

- APMSF

p-amidi-nophenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride

- Con A

concanavalin A

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- MALDI-TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

References

- Andersson K, Sun S, Boman HG, Steiner H. Purification of the prophenol oxidase from Hyalophora cecropia and four proteins involved in its activation. Insect Biochem. 1989;19:629–637. [Google Scholar]

- Asada N, Fukumitsu T, Fujimoto K, Masuda K. Activation of prophenoloxidase with 2-propanol and other organic compounds in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1993;23:515–520. doi: 10.1016/0965-1748(93)90060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashida M, Brey PT. Recent advances on the research of the insect prophenoloxidase cascade. In: Brey PT, Hultmark D, editors. Molecular Mechanisms of Immune Responses in Insects. London: Chapman & Hall; 1998. pp. 135–172. [Google Scholar]

- Decker H, Ryan M, Jaenicke E, Terwilliger N. SDS-induced phenoloxidase activity of hemocyanins from Limulus polyphemus, Eurypelma californicum, and Cancer magister. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:17796–17799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Wang Y, Jiang H. Purification and characterization of Manduca sexta prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-1 (PAP-1), an enzyme involved in insect defense responses. Protein Expression and Purification. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.10.011. manuscript accepted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TS, Wang H, Lee SY, Johansson MW, Söderhäll K, Cerenius L. A cell adhesion protein from the crayfish Pacifastacus leniusculus, a serine proteinase homolog similar to Drosophila masquerade. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:9996–10001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.9996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Kanost MR. Characterization and functional analysis of 12 naturally occurring reactive site variants of serpin-1 from Manduca sexta. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:1082–1087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Ma C, Kanost MR. Subunit composition of pro-phenol oxidase from Manduca sexta: molecular cloning of subunit proPO-p1. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1997;27:835–850. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(97)00066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Kanost MR. Pro-phenol oxidase activating proteinase from an insect, Manduca sexta, a bacteria-inducible protein similar to Drosophila easter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1998;95:12220–12225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Yu X-Q, Kanost MR. Prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-2 (PAP-2) from hemolymph of Manduca sexta: a bacteria-inducible serine proteinase containing two clip domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2003a;278:3552–3561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wang Y, Yu X-Q, Zhu Y, Kanost MR. Prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-3 (PAP-3) from Manduca sexta hemolymph: a clip-domain serine proteinase regulated by serpin-1J and serine proteinase homologs. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003b;33:1049–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(03)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MS, Baek MJ, Lee MH, Park JW, Lee SY, Söderhäll K, Lee BL. A new easter-type serine protease cleaves a masquerade-like protein during prophenoloxidase activation in Holotrichia diomphalia larvae. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:39999–40004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Söderhäll K. Characterization of a pattern recognition protein, a masquerade-like protein, in the freshwater crayfish Pacifastacus leniusculus. J. Immunol. 2001;166:7319–7326. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Kwon TH, Hyun JH, Choi JS, Kawabata S, Iwanaga S, Lee BL. In vitro activation of pro-phenoloxidase by two kinds of pro-phenol-oxidase-activating factors isolated from hemolymph of coleopteran, Holotrichia diomphalia larvae. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;254:50–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KY, Zhang R, Kim MS, Park JW, Park HY, Kawabata S, Lee BL. A zymogen form of masquerade-like serine proteinase homologue is cleaved during pro-phenoloxidase activation by Ca2+ in coleopteran and Tenebrio molitor larvae. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:4375–4383. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Kawabata S. A link between blood coagulation and prophenol oxidase activation in arthropod host defense. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:29264–29267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Osaki T, Kawabata S. Functional conversion of hemocyanin to phenoloxidase by horseshoe crab antimicrobial peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:27166–27170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh D, Horii A, Ochiai M, Ashida M. Prophenoloxidase-activating enzyme of the silkworm, Bombyx mori: purification, characterization and cDNA cloning. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7441–7453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderhäll K, Cerenius L. Role of the prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrate immunity. Curr. Opin.Immunol. 1998;10:23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jiang H. Prophenoloxidase (proPO) activation in Manduca sexta: an analysis of molecular interactions among proPO, proPO-activating proteinase-3, and a cofactor. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;34:731–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Lee SY, Cerenius L, Söderhäll K. Properties of the prophenoloxidase activating enzyme of the freshwater crayfish, Pacifastacus leniusculus. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:895–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Kanost MR. Immulectin-2, a lipopolysaccharide-specific lectin from an insect, Manduca sexta, is induced in response to gram-negative bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:37373–37381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Jiang H, Wang Y, Kanost MR. Nonproteolytic serine proteinase homologs are involved in phenoloxidase activation in the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;33:197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]