Abstract

As adulterated and substituted Chinese medicinal materials are common in the market, therapeutic effectiveness of such materials cannot be guaranteed. Identification at species-, strain- and locality-levels, therefore, is required for quality assurance/control of Chinese medicine. This review provides an informative introduction to DNA methods for authentication of Chinese medicinal materials. Technical features and examples of the methods based on sequencing, hybridization and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are described and their suitability for different identification objectives is discussed.

Background

Chinese medicinal materials have long been used for disease prevention and therapy in China and are becoming increasingly popular in the West [1-3]. The annual sales of herbal medicines have amounted to US $7 billion in Europe and those in the United States increased from US $200 million in 1988 to more than US $3.3 billion in 1997 [4]. Despite the belief that Chinese medicines are of natural origin which have few adverse effects, there have been numerous reports on adverse effects associated with herbal remedies [5]. One possible cause is the variable quality of both crude medicinal materials (plants, fungi, animal parts and minerals) and Chinese proprietary medicines. Many substitutes and adulterants are in the market due to their lower costs or misidentification caused by similarity in appearance with their authentic counterparts. It is particularly difficult to identify those medicines derived from processed parts of organisms and commercial products in powder and/or tablet forms. Some of the adulterants or substitutes caused intoxications and even deaths [6-8]. Moreover, it is also common for several species to have the same name [9-12]. Inadvertent substitution of these species can also lead to intoxication [13]. Adulterants and substitutes may have completely different or weaker pharmacological actions compared with their authentic counterparts; even different species of the same genus may have totally different actions. For example, Panax ginseng (Renshen), considered to be 'hot', is used in 'yang-deficient' conditions, while Panax quinquefolius (Xiyangshen) [14], considered to be 'cool ', is used in 'yin-deficient 'conditions. Authentication of Chinese medicinal materials is the key to ensure the therapeutic potency, minimize unfair trade and raise consumers' confidence towards Chinese medicine in general.

Locality-level identification is also of great importance to ensure highest therapeutic effectiveness. 'Daodi' is a Chinese term describing the highest quality of herbal materials that are collected from the best region and at the best time [15]. Chinese medicinal materials cultivated in different localities differ in therapeutic effectiveness. For example, it is well accepted that Atractylodes macrocephala (Baizhu) grown in Jiangning, Jiangshu province, China is more effective than those grown in Zhejiang and Jiangxi provinces [16]. Condonopsis pilosula (Dangshen) grown in Shanxi province is generally considered to be more potent than those grown in other provinces [16]. Furthermore, samples from the same localities are probably of the same strains; therefore, origin identification helps select the best strains of Chinese medicinal materials. There have been a number of studies investigating medicinal materials grown in different geographical regions. Codonopsis pilosula (Dangshen) [16], Panax notoginseng (Sanqi) [15], Bufo bufo gargarizans (Chansu) [17] and Paeonia lactiflora (Baishao, or Chishao) [18] are just a few examples.

DNA methods for identification of Chinese medicinal materials

One of the most reliable methods for identification of Chinese medicinal materials is by analyzing DNA that is present in all organisms. DNA methods are suitable for identifying Chinese medicinal materials because genetic composition is unique for each individual irrespective of the physical forms of samples, and is less affected by age [19], physiological conditions, environmental factors [20-22], harvest [19], storage and processing [23-31]. DNA extracted from leaves, stems or roots of a herb all carry the same genetic information [32]. In general, extracted DNA is stable and can be stored at -20°C for a long period of time (about 3–5 years), hence eliminating the time constraint in performing the analysis. A small amount of sample is sufficient for analysis and this is advantageous for analyzing medicinal materials that are expensive or in limited supply [32,33].

In terms of the mechanisms involved, DNA methods can be classified into three types, namely polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based, hybridization-based and sequencing-based.

PCR-based method

PCR-based methods use amplification of the region(s) of interest in the genome; subsequent gel electrophoresis is performed to size and/or score the amplification products.

PCR-based methods have the advantage of requiring tiny amounts of samples for analysis due to the high sensitivity of PCR. However, PCR inhibitors (e.g. polyphenols, pigments and acidic polysaccharides) may be present in DNA samples, thereby hampering amplification. Moreover, PCR is prone to contamination because of its high sensitivity [34]. DNA from contaminating bacteria or fungi in some improperly-stored medicinal samples may be co-amplified if the stringency used is not high enough.

PCR-based methods include sequence characterized amplified regions (SCAR), amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS), simple sequence repeat (SSR) analysis and DNA fingerprinting methods.

DNA fingerprinting

DNA fingerprinting refers to simultaneous analysis of multiple loci in a genome to produce a unique pattern for identification. These methods include PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP), random-primed PCR (RP-PCR), direct amplification of length polymorphism (DALP), inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR), amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) and directed amplification of minisatellite-region DNA (DAMD). Except PCR-RFLP and DAMD, these methods share the following characteristics:

• Suitable for Chinese medicinal materials which lack DNA sequence information, as they do not require prior sequence knowledge

• Large numbers of loci can be screened in a short time

• Require DNA of good quality, in terms of DNA integrity and the absence of PCR inhibitors

• Unknown origins of the sequences

• Can be used to show the phylogenetic relationships among organisms within the same genus

PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP)

PCR-RFLP uses endonucleases to digest PCR products of regions with sequence polymorphisms. By using an endonuclease which recognizes and cleaves at the polymorphic sites, the digestion of a longer PCR fragment into smaller fragments will change the banding pattern. PCR-RFLP has been used for authentication of Panax species [14,35,36], Fritillaria pallidiflora [37], Atractylodes species [38] and differentiation of Codonopsis from their adulterants [39].

Screening PCR products by using various restriction enzymes can be an alternative of sequencing to find out polymorphic regions among samples [34,40]. This method is more reproducible than random priming methods, but it is limited by the degree of polymorphism among individuals within a species [25]. The loss of restriction sites associated with degraded DNA, creation or deletion of restriction sites due to intra-specific variation [34], and the presence of enzyme inhibitors may lead to incomplete digestion.

Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP)

AFLP involves restriction of genomic DNA and ligation to adapters, selective amplification of restriction fragments using primers containing the adapter sequences and selective bases at the 3' terminals, and subsequent gel analysis of the amplified fragments [41]. The number of resulting fragments in this multi-locus approach is determined by the number and composition of selective nucleotides as well as the complexity of the genomes. Polymorphisms detected may be caused by a single nucleotide change at the restriction site or 3' end of the primer binding site, insertions and deletions as well as rearrangements. It has been used for authentication [42] and studying genetic diversity [43-46] of Chinese medicines.

AFLP combines the advantages of the reliability of RFLP and the power of PCR. The high reproducibility resulting from stringent reaction conditions enables the use of polymorphic bands in developing cultivar-specific probes, which can then be used for easy identification [47]. By using adapter sequences, fingerprints can be generated without prior sequence knowledge. The number of amplified fragments can be controlled by changing the restriction enzymes and the number of selective bases and thus this method is suitable for DNA of any origin and complexity. It is efficient in revealing polymorphisms even between closely related individuals [48]. The number of polymorphisms per reaction can be higher than RFLP or RAPD [47,49]. Three steps and four different primers are required for analysis of complex genomes [48]. Imperfect ligation or incomplete restriction of DNA will lead to artifactual polymorphisms because of partial fragments [48]. Moreover, if the sequence homology between two organisms is less than 90%, their fingerprints will share very few common fragments [50].

Random-primed PCR (RP-PCR)

RP-PCR involves amplification at low annealing temperatures using one or two random primers in each PCR reaction to generate unique fingerprints (Figure 1). At reduced stringency, the arbitrary primers bind to a number of sites randomly distributed in the genomic DNA template although the primer and the template sequences may not be perfectly matched. Each anonymous and reproducible fragment is derived from a region of genome that contains, on opposite DNA strands, two primer binding sites located within an amplifiable distance from each other. Polymorphisms are resulted from sequence differences which inhibit primer binding or interfere with amplification. The presence or absence of bands is scored and the results can be used for calculating genetic distances [51-53] and constructing phylogenetic trees [18,54] to study the relationships among samples.

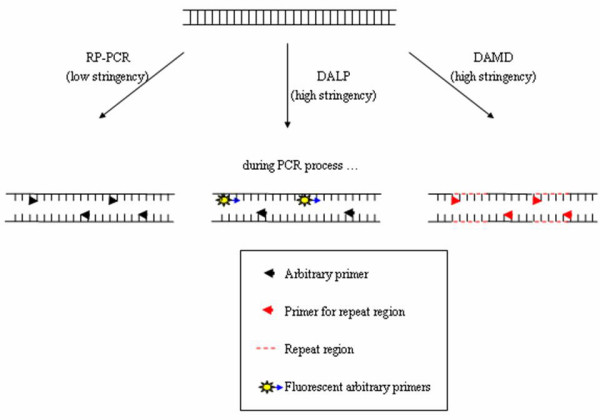

Figure 1.

RP-PCR, DALP and DAMD. RP-PCR employs low stringency conditions and unlabeled arbitrary primers, while DALP employs high stringency conditions and both fluorescent-labeled and unlabeled arbitrary primers. DAMD employs high stringency conditions and an unlabeled primer targeting repeat regions.

Techniques based on this concept include arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR) [55], random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) [56] and DNA amplification fingerprinting (DAF) [57]. AP-PCR employs primers of approximately 20 nucleotides long and only two relaxed PCR cycles while RAPD employs primers of 10 nucleotides long and all the PCR cycles are relaxed, and DAF employs primers of 5–8 nucleotides long and all the PCR cycles are relaxed with lower stringency than that of RAPD. AP-PCR results are the most reproducible among these three methods.

As any part of the genome, including non-coding regions, may be amplified, these methods can be used to discriminate between closely related individuals. RP-PCR have been used for marker-assisted selection in breeding [58], identification at the individual, variety, strain and species levels [51,59-62], study of genetic diversity [63,64] and differentiation of cultivated and wild samples [18,65,66]. It has been used to authenticate Chinese medicines [51,52,67-69] and identify their geographical origins [16,18,53,70,71].

RP-PCR is a quick and easy method to screen a large number of loci for DNA polymorphisms in a single PCR. Polymorphic markers can be generated rapidly without sequence information. The marker sequences obtained from RP-PCR can also be used to design specific oligonucleotides to be used in SCAR assay [72]. Moreover, any single primer can be used, including those for specific PCR amplification or sequencing. However, there are some limitations in RP-PCR. Firstly, it is sensitive to the reaction conditions, including the amounts of templates [73-75] and magnesium ions [76,77], the sequences of primers [78-81], the presence of glycerol [82] and the quantity and quality of the polymerase [83]. Thermocyclers may also influence the banding patterns due to their different ramp time from the annealing step to the extension step [84,85]. Therefore, results generated with different reaction conditions cannot be compared directly. Secondly, the reproducibility of RP-PCR patterns can be influenced by the quality, quantity and purity of DNA templates [86,87]. Some researchers consider this to have a more significant effect to reproducibility than other factors such as enzyme quality or buffer conditions which may affect only the relative intensities of bands, but do not cause a band to appear or disappear [88]. The number of bands produced can be greatly increased by adding bovine serum albumin (BSA), which prevents various contaminants in impure DNA from binding to Taq polymerase [89] thereby stabilizing the polymerase [90]. This method is, therefore, unreliable for identification of medicinal materials with impure or degraded DNA [91] caused by processing or long storage time. Amplification should be performed using DNA templates at two concentrations with at least two-fold difference [92] to ensure reproducibility of the results. Thirdly, as arbitrary primers and low stringencies are used, DNA from any organisms including DNA from contaminants can be amplified, thereby contributing to the banding pattern. Fourthly, as different loci in the genome have different degree of homology among samples (e.g. coding regions are more conserved), the number of loci to be included should be large enough to reveal differences in the whole genome. Fifthly, fragments of the same size in the fingerprints are not necessarily the same sequence [93]. It should not be assumed that bands of a similar size are homologous sequences, especially when distant species are being examined. The extent of polymorphism is indicated by the presence and absence of bands of particular sizes and thus applying RP-PCR on high taxonomic levels leads to an increase in variance of genetic distance estimates.

Direct amplification of length polymorphism (DALP)

DALP uses a selective forward primer containing a 5' core sequence (e.g. M13 universal sequencing primer) plus additional bases at the 3' end and a common reverse primer (e.g. M13 reverse primer) to generate multibanded patterns in denaturing polyacrylamide gel [48]. For identification of fragments having two different ends, two PCR reactions are performed for each sample, with each reaction containing either of the primers labeled. The common bands in both labeled reactions are the products having two different ends. Any of these bands can be excised from the gel and sequenced directly using forward or reverse primers. After sequencing the polymorphic bands among the samples, species- or strain-specific primers can be designed. These specific primers can then be used for mono-locus amplification (i.e. sequence-tagged site) (Figure 2). DALP is similar to AP-PCR except that it uses higher stringency (i.e. higher annealing temperature, lower concentration of magnesium ion and fewer cycles). At this stringency, a given arbitrary primer will anneal to fixed sites across experiments [48]. Moreover, the polymorphic bands can be sequenced directly to further design species- or strain-specific primers, whereas in AP-PCR the two ends of the products contain the same primer sequence. For this reason, AP-PCR products cannot be sequenced directly (Figure 1). DALP has been used to detect polymorphisms between species [48,94] and between strains [48] and to authenticate Panax ginseng (Renshen) and Panax quinquefolius (Xiyangshen) [95]. It has also been used in mapping for marker-assisted selection in breeding [96].

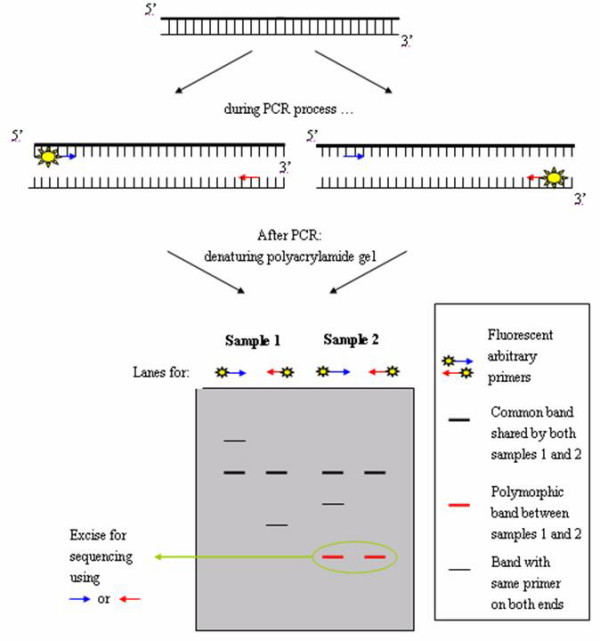

Figure 2.

DALP. DALP employs two separate PCRs, each containing one of the primers labeled, for each sample. After separation in denaturing polyacrylamide gel, bands shared by the two reactions are products with different primers at both ends. These bands are compared with those of other samples in order to find the polymorphic bands among the samples. Polymorphic bands can be excised from the gel and sequenced directly using either of the primers.

Identification of polymorphic products can be done easily by searching in public sequence databases. However, each sample must be subject to two separate PCR reactions by alternative labeling of the two primers. This requires an additional step apart from identifying polymorphic bands among samples. Unlike RP-PCR, much time and effort are required in screening for suitable primer pairs and optimizing primer ratio [97].

Inter-simple sequence repeats (ISSR)

ISSR [98] employs a primer containing simple repeat sequences for PCR amplification to generate fingerprints (Figure 3). The primer can be 5' or 3' anchored by selective nucleotides to prevent internal priming of the primer and to amplify only a subset of the targeted inter-repeat regions, thereby reducing the number of bands produced by priming of dinucleotide inter-repeat region [98-100]. Therefore regions between inversely oriented closely spaced microsatellites are amplified [101]. This method relies on the existence of 'SSR hot spots' in genomes [98,101]. It has been used in the authentication of Dendrobium officinale (Tiepi Shihu) [102] and in the studies of genetic variations and relationships [103-106].

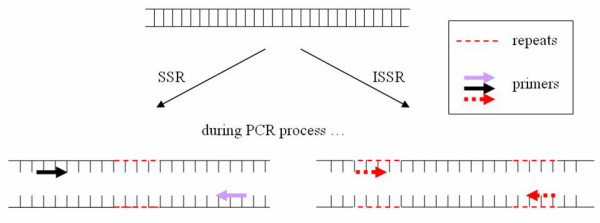

Figure 3.

SSR and ISSR. SSR employs primers targeting a single repeat region, while ISSR employs a single primer containing repeats to amplify regions between two repeats.

As simple sequence repeats exist in any genome, this method allows fingerprints to be generated for any organism. However, the primers may anneal to sequences other than microsatellites of the desired repeats as in RAPD [99]. Moreover, the banding patterns can be affected by magnesium ion concentration, thermocycler and annealing temperature in use [102]. Compared to SSR markers, ISSR markers are not locus-specific and anonymous bands are produced in the fingerprints [101].

Directed amplification of minisatellite-region DNA (DAMD)

Minisatellites are also known as variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR). They are similar to microsatellites except that the repeat unit sequence is longer than 10 bp (the distinction between microsatellites and minisatellites is often arbitrary with repeat units between 8 and 15 bp [107]). DAMD [108] is a DNA fingerprinting method based on amplification of the regions rich in minisatellites at relatively high stringencies by using previously found VNTR core sequences as primers (Figure 1). It is employed in identification of species-specific sequences [109]. The method has been used for authentication of Panax ginseng (Renshen) and Panax quinquefolius (Xiyangshen) [42] and characterization of varieties [78] and cell lines [110].

Similar to SSR, minisatellites are present in all organisms, making it possible to apply this method to any genome. Examples include plants such as mulberry [78] and oilseed [109], mushrooms Agaricus bisporus and Pleurotus [111], animals such as human, snake and mouse [110], insects such as mosquito and moth. This method is more reproducible than RAPD due to the longer primers used [111]. However, similar to ISSR, it only reveals polymorphisms in the regions rich in repetitive sequences, while RP-PCR can represent the polymorphisms of the whole genome [78]. Moreover, polymorphic sequence must be obtained by cloning polymorphic bands prior to sequencing because of the same primer sequences at both ends of the PCR product.

Sequence characterized amplified regions (SCAR)

SCAR [72] can be used for detection or differentiation of samples by using specific primers designed from polymorphic RAPD [72,112] or ISSR [113,114] fragments for PCR, leading to positive or negative amplification in target-containing and non-target-containing samples respectively [112,115] or amplification products of different sizes in the case of closely related samples [91,116]. This method has been used for authentication of Panax [91] and crocodilian species [115], and for discrimination of Artemisia princeps (Kuihao) and Artemisia argyi (Aiye) from other Artemisia herbs [112].

SCAR markers are more reproducible than RAPD markers, and they are straightforward for data interpretation. As little DNA is required for PCR, DNA extraction must be performed on a sample representative of the mix in order to accurately detect a target in a mixture. Prior sequence information (i.e. sequencing the polymorphic fragments) is required for designing the primers flanking the polymorphic region. As PCR inhibitory effects of ingredients in Chinese medicine can lead to false negative results, amplification of a control fragment using the same DNA template [114,115] or spiking control DNA amplifiable by the same primers to the sample DNA should be performed to ensure that the quality of sample DNA is suitable for PCR.

Amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS)

ARMS [117] is also known as allele-specific PCR (AS-PCR) [118]. It refers to PCR amplification using primers which differ in the 3' terminal for distinguishing related samples. This method is based on the fact that mismatches at the last base(s) at the 3' terminal of primers can lead to failure in PCR [119,120]. It has been used to identify Panax species [121] and Curcuma (Ezhu) species [122] using primers based on chloroplast trnK and nuclear 18S rRNA genes. ARMS based on mitochondrial cytochrome b gene has been used for detection of tiger bone DNA [123]. It has also been used for distinguishing Myospalax baileyi [124] and gecko [125] from their substitutes and adulterants.

This method is simple, rapid and reliable [117]. However, as the absence of bands is also considered as a positive result for detection experiments, appropriate positive controls should be included to show that the reagents have indeed worked properly and that the PCR process was not problematic. PCR inhibitory effects leading to false negative results can be identified by parallel testing of samples spiked with tiny quantities of pure target DNA to demonstrate the level of detection [123].

Simple sequence repeats (SSR) analysis

SSR analysis is also referred to as simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP). SSR [126,127] is also known as microsatellites, short tandem repeats and sequence-tagged microsatellite sites (STMS) which are short tandem repeats of 2–8 nucleotides [128,129] or 1–6 nucleotides [130-132] widely and abundantly dispersed in most nuclear eukaryotic genomes [130,133,134]. Changes in repeat numbers at SSR loci are much more frequent than normal mutation rate [101,135,136] because of slippage [133,136-138] and recombination [133,138-140]. The different numbers of repeating units (alleles) in polymorphic loci lead to variation in band sizes (length polymorphism) when specific flanking primers designed based on conserved sequences are used for amplification of the loci in organisms of the same species. The presence or absence of each allele at each locus can be scored digitally. Figure 3 shows the procedural differences between ISSR and SSR.

SSR analysis has been applied in authentication of ginseng [25,141]. In SSR analysis, Panax quinquefolius (Xiyangshen) showed different allele patterns compared with those of Panax ginseng (Renshen). Moreover, cultivated and wild Panax quinquefolius (Xiyangshen) can be distinguished from each other [141]. This method has also been used in characterization of germplasm resource of Gastrodia elata (Tianma) [142] and studying genomic variation in regenerants of Codonopsis lanceolata (Dangshen) [104]. Due to its ability for analysis at low taxonomic levels, it has been applied to breeding programs [143].

SSR loci are highly polymorphic [101,144]. In bread wheat, loci with 4 to 40 alleles have been found for 480 varieties [145], with an average of 16.4 alleles. It is possible to multiplex 17 loci in a single PCR reaction [146]. As the primers are designed according to conserved sequences, they may be successfully applied for related species [147,148] and sometimes across genera [147,149]. Moreover, the primers can be accessible to other laboratories via published primer sequences [150-152]. Besides the advantages of employing PCR and the high reproducibility, this technique can be fully automated (including automated sizing of PCR products by fluorescence-based detection) and fitted into large-scale, high throughput authentication centers [25].

Size differences can also be caused by insertions and deletions, and duplication events in the flanking sequences [153-155]. However, high initial investment and technical expertise are required for development of SSR markers [156-158]. Although SSR markers can be identified by screening DNA [150,159,160] or EST sequence databases [161-163], sequence information is not available for most Chinese medicinal species. Without sequence information, SSR marker development involves either constructing enriched genomic libraries [142,147,149,164], ISSR genomic pools [165,166] or Southern hybridization-screened RAPD genomic pools [167,168] followed by cloning and sequencing. However, the identified loci may not be polymorphic or informative [169]. Moreover, null alleles (i.e. loss of PCR products occurring due to mutations in the primer binding sites) may be encountered [143,150,158] even when using SSR markers developed from the same species [170].

Sequencing-based methods

Much information can be obtained from DNA sequences [34]. DNA sequences can be used for studying phylogenetic relationships among different species [70,171,172]. Sequencing also allows detection of new or unusual species [34,173]. Another advantage of using sequencing for species identification is that the identities of adulterants can be identified by performing sequence searches on public sequence databases such as GenBank. By database searching, Mihalov et al. [174] successfully identified soybean substituted for ginseng (Panax species) in commercial samples. However, prior sequence knowledge is required for designing primers for amplification of the region of interest [34].

DNA sequencing can be used to assess variations due to transversions, transitions, insertions or deletions. Different regions in the genome evolve at different rates, which are useful for identification at different taxonomic levels [33]. Regions that do not code for proteins are under lower selective pressure and thus can be more variable. The more variable is a particular region, the more closely related individuals can be differentiated by this region. Regions commonly used include rRNA genes, mitochondrial genes and chloroplast genes [175]. There are more than 100 copies of these genes in a cell, which evolve inter-dependently (i.e. concerted evolution [176-178], previously known as horizontal evolution [179] in the case of rRNA genes, and homoplasmy [180,181] in the cases of mitochondrial and chloroplast genes). Thus, methods using these regions are highly sensitive and amplifications are facilitated. This is also advantageous during PCR amplification of medicinal samples with degraded DNA because the presence of one full-length copy in a reaction is theoretically enough for amplification. Moreover, the conserved sequences flanking the genes are useful for designing 'universal' primers to be used for amplifying and sequencing the genes from many species [182-185].

rDNA sequences have been used for studying Chinese medicines such as Panax species [35,186-188], Eucommia ulmoides (Duzhong) [189], Cordyceps (Dongchongxiacao) species [190], Dendrobium (Shihu) species [191], Myospalax baileyi [192] and Ligusticum chuanxiong (Chuanxiong) [193]. The chloroplast sequences have been used for studying Curcuma (Ezhu) species [194], Panax notoginseng (Sanqi) [67,188], Adenophora (Shashen) species [195] and Atractylodes (Cangzhu) species [38]. The mitochondrial sequences have been used for studying Bungarus parvus [196], Hippocampus species [197] and turtle shells [198].

Hybridization-based methods

Nucleic acid hybridization is a process in which two complementary single-stranded nucleic acids anneal into a double-stranded nucleic acid through the formation of hydrogen bonds. DNA hybridization has been used for detection of Dendrobium (Shihu) species by incorporating a species-specific region of reference samples on a glass slide and subsequent hybridization of the region amplified from a complex mixture of medicinal materials using universal primers [199]. Besides Dendrobium (Shihu) [200], it has also been used to identify Fritillaria (Chuanbeimu) species [201] and toxic Chinese medicinal materials such as Datura (Yangjinhua) species [202,203], Pinellia (Banxia) species [33,202] and others[202,204].

With DNA hybridization, detection from a variety of possible species is feasible [204]. Detection of the presence of multiple species in admixtures [205,206] and in a wide range of commercially processed, heated and canned food products have also been demonstrated [206-208]. Moreover, DNA hybridization has been used to identify organisms of different breeds [209]. If the probes are oligonucleotides shorter than 100 bases, hybridization is possible even after a considerable level of DNA degradation [34]. However, a relatively large amount of DNA is required and the process is time-consuming (because the hybridization step typically requires overnight incubation) [34] and labor-intensive compared to PCR-based methods. If the experimental conditions are not stringent enough, cross-hybridization with highly similar but not identical targets may also occur [204,210,211], resulting in false-positive results. Furthermore, only a limited number of probes can be applied in one hybridization experiment [212,213] for most hybridization methods. As a result, much time has to be spent on testing a large number of probes and checking for false-positives and false-negatives. Despite the fact that microarray hybridization has a high throughput, it is still quite expensive.

Comparison of methods

Level of identification

The level of identification by a certain method largely depends on its targeted region in the genome and its mechanism and principle of analysis. Species-specific regions, such as internal transcribed spacers (ITS) and 5S rRNA spacer regions of ribosomal DNA, mitochondrial cytochrome b and chloroplast trnL-trnF spacer regions, have been used for species-level identification by sequencing [53,70,174], microarray hybridization [199,204] and PCR [123]. SCAR, in which the species-specific bands generated from fingerprints are used for primer construction [91,112], is applicable to species-level identification. However, techniques based on differences of several bases, such as ARMS and PCR-RFLP, can be applied to species-level identification or lower even when more conserved genes are employed, as long as sufficient polymorphic nucleotides can be found in the genes. For example, 18S ribosomal gene has been used for PCR-RFLP for differentiation of Panax ginseng (Renshen) from 4 localities [36]. The chloroplast trnK gene and the nuclear 18S rRNA gene have been used for ARMS to identify Panax species [121] and Curcuma (Ezhu) species [122].

Except for PCR-RFLP, fingerprinting methods can only be used to discriminate among closely related individuals, mostly on population [214,215], strain and locality [36,53,59,62] levels. However, if scoring of bands for further processing is not required, fingerprinting methods can be applied in differentiation at the species level [51,60] by banding pattern comparison with reference materials.

SSR analysis can be used in identification of species within the same genus [25,141], at the variety and cultivar level [143,145,216] as well as at the individual level [217,218]. It is not used for comparing species of different genus because the sequences of the amplification products can be quite different even if the primers can successfully amplify PCR products [153,219]. ISSR involves amplification of regions between SSR loci and can be used for authentication at population [102,220,221] and species levels [222,223].

Choice of method

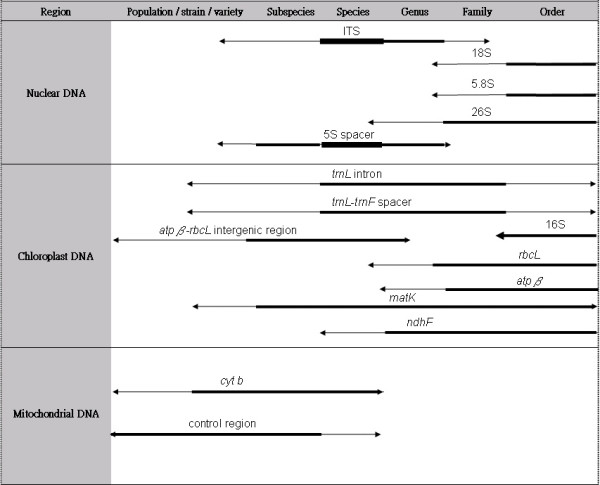

Table 1 summarizes the methods mentioned in this article. Each method has its own advantages and limitations. Decisions as to which method to use should be based on the aim, the DNA quality of the obtained sample and the cost of implementation (e.g. whether prior sequence knowledge is obtainable and required). A diagram showing the technical considerations affecting the choice of method is provided in Figure 4. Besides method selection, choosing a suitable DNA region for analysis is also crucial in obtaining good results (Figure 5). It should be noted that the exact taxonomic levels the regions can be applied to depend on the choice of method, and that successful application on a species does not guarantee successful application on other species at the same taxonomic level.

Table 1.

Comparison of various DNA methods (adapted from [135, 237, 245, 247])

| SCAR | ARMS | SSR | PCR-RFLP | RP-PCR | ISSR | AFLP | Sequencing | Hybridization | |

| Development cost | medium | medium | high | medium a | low | low | low | medium | medium |

| Running cost | low | low | medium | medium a | low | low | medium | medium | medium |

| Polymorphism | low b | low c | high d | low e | medium f | medium f | medium f | medium-low g | only for detection h |

| Detection of contamination by DNA of the same target species (mixture) | no | no | yes | yes/noi | no | no | no | yes/nok | yes/nok |

| Detection of contamination by non-target species DNA (mixture) | no | no | no | yes j | no | no | no | yes/nok | yes/nok |

| Detection of contamination by DNA of the same target species (mixture) | no | no | yes | yes/no i | no | no | no | yes/nok | yes/nok |

| Detection of contamination by non-target species DNA (mixture) | no | No | no | yesj | No | no | no | yes/nok | yes/nok |

| Multi-locus/single locus | single locus | single locus | single locus | single locus | multi-loci | multi-loci | multi-loci | single locus | single locus |

| Level of identification (taxonomic level) | species | species to strain | strain | species to strain | species to strain | species to strain | species to strain | family to strain | genus to subspecies |

| Quality of DNA required (integrity) | medium | medium | low | medium | high | high | high | medium | medium |

| Quality of DNA required (purity) | high l | high l | medium | high | high | high | high | high l | high |

| Prior sequence knowledge requirement (including universal primer sequence) | yes | yes | yes | no | no | no | no | yes | yes |

| Throughput | low | low | high | low | high | high | high | low | high |

| Level of skills required | low | low | low-medium | low | low | low | medium | medium | medium |

| Automation | yes | yes | yes | difficult | yes | yes | yes | yes | difficult |

| Reliability | high | high | high | high | low | medium | high | high | medium |

Development cost: cost for developing standardized reference results for target samples

Running cost: cost for routine testing

Detection of contamination: same target species = samples of the same strain or locality; non-target species = adulterants or substitutes

Multi-locus: simultaneous amplification of multiple regions in the genome in a single PCR

Prior sequence requirement: sequence requirement to design primers for amplification or probes for hybridization

Throughput: number of samples that can be handled within a given period of time

Reliability: giving reproducible and accurate results under the same conditions

a: enzyme dependent

b: band/no band, or size polymorphism

c: band or no band

d: null allele or size polymorphism

e: band number and size polymorphism

f: presence/absence of all the bands in a pattern

g: sequence dependent; nucleotide difference

h: presence or absence of sample DNA

i: restriction enzyme dependent

j: primer dependent

k: sequence dependent

l: crude tolerated

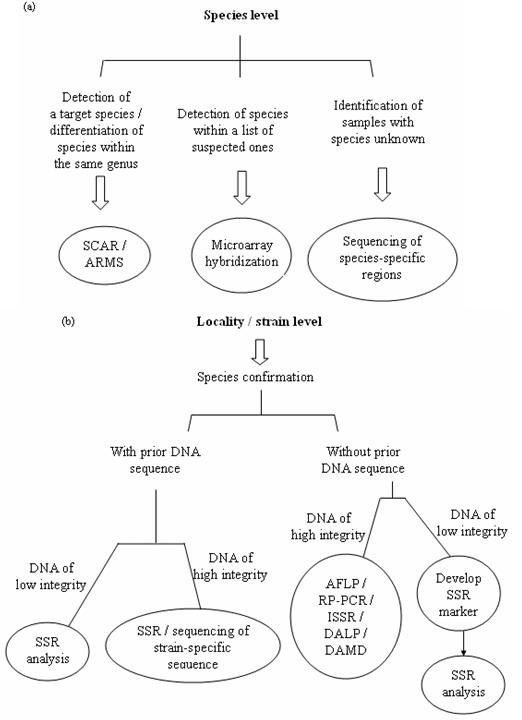

Figure 4.

Selection of appropriate molecular identification methods for (a) species and (b) locality/strain levels. a) For species level, SCAR and ARMS are suitable for detection of a target species or differentiation of species within the same genus. Microarray hybridization is suitable for detection of species within a list of suspected ones. Sequencing of species-specific regions is suitable for identification of samples with its species totally unknown. b) For locality or strain level, species identification should be performed first. Then, depending on whether prior sequence knowledge is available and the integrity of the DNA samples, different methods can be applied. SSR analysis and sequencing of strain-specific sequences are suitable for samples with primer sequences already available and SSR analysis is especially suitable for samples with DNA of low integrity. For samples without prior sequence knowledge, SSR marker development followed by subsequent SSR analysis can be applied for DNA samples of low integrity, while AFLP, RP-PCR, ISSR, DALP and DAMD can be applied for DNA samples of high integrity.

Figure 5.

Comparison of various regions for use on various taxonomic levels (adapted from [244-246]). The thickness of the lines represents how frequently the regions are used for identification at the levels. The exact taxonomic levels that the regions can be applied to depend on the selected method. Successful application on a species does not guarantee successful application on other species at the same taxonomic level. For nuclear DNA regions, 18S and 5.8S regions are usually used for identification to the order or family levels and 26S is usually used for the order level down to the species level. The two ITS regions and the 5S spacer region are commonly used for identification at the species level, but they can also be applied down to the population/strain/variety level. For chloroplast DNA regions, 16S is suitable for the order level, while rbcL, atpβ and ndhF are suitable for the levels from order to species. The trnL intron, trnL-trnF spacer and matK regions can be applied to the levels from order to population/strain/variety, but the former two are more commonly used for the levels from family to species, while the latter is commonly used for the levels from order to subspecies. The atpβ-rbcL region can be used for the levels from genus to population/strain/variety, but it is more commonly used for the levels from genus to subspecies. For mitochondrial regions, cytochrome b and the control region can be used for identification at the levels from species to population/strain/variety, but the former is more commonly used for the species level and the latter is more commonly used for the subspecies level and lower.

Problems faced for using DNA in identification

While DNA methods are excellent for identifying Chinese medicinal materials of various forms, certain problems remain to be solved. DNA degradation is common for those materials that have been heat-treated [123,224-226] by frying, sun-drying, oven-drying or milling without cooling, treated with various chemicals and stored for a long time in various conditions. This problem may be overcome by choosing more degradation-tolerant methods, one of which is employing multi-copy genes (e.g. ribosomal and mitochondrial genes) [227] so that the chances of getting some full-length copies are higher. The mitochondrial genes are also suitable because mitochondria are relatively intact during processing [228]. Another approach is to analyze small regions of DNA by methods such as SSR analysis [229,230], which may target sequences as short as several tens of base pairs of DNA and the chances of breakage within the target region are minimal [231-233]. Hybridization is also useful in identification of degraded DNA [206,207].

The presence of PCR inhibitors is a problem. Chinese medicinal materials are usually (1) plants that may contain phenolic compounds, acidic polysaccharides and pigments, (2) fungi which may contain acidic polysaccharides and pigments, or (3) animal remains which may contain fat and complex polysaccharides. Choosing the most suitable DNA extraction procedures for the types of samples may help eliminate the PCR inhibitors [234-237]. Other possible solutions are diluting the extracted DNA and adding PCR enhancers.

Contamination by non-target DNA of bacteria, fungi or insects due to improper storage or by other medicinal materials in formulations is another challenge. This creates the biggest problem for fingerprinting methods because the DNA of the contaminants will be amplified. This may be overcome by using methods specific for the target such as ARMS and SCAR. If the region of analysis is species-specific and the stringency is high enough, microarray analysis is also an alternative for studying DNA mixtures [199,238]. However, DNA degradation by microbes cannot be avoided in contaminated samples [239].

DNA information is not directly correlated with the amounts of active ingredients. However, genetic data have its own advantages (as discussed above) over other methods for authentication and identification.

There are successful cases of using DNA methods to identify Chinese medicines, such as Panax [174,186,240] (Table 2), crocodilian species [115] and Dendrobium (Shihu) species [200,241] in commercial products. DNA methods can also be used to identify components in concentrated Chinese medicine preparations in which the components have been grounded, boiled, filtrated, concentrated, dried and blended [242]. By applying appropriate methods and regions of genome, problems in authentication of Chinese medicinal materials can be solved.

Table 2.

DNA methods for identification of Panax species

| Techniques | Samples to differentiate | Prerequisite | Summary of results | Year of publication | Ref |

| PCR-RFLP | Six Panax species and adulterants | ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 sequences | The polymorphisms in the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 sequence among the samples can be shown using various restriction enzymes to create species-specific RFLP profiles. Ten per cent of contamination of P. ginseng was detected from P. quinquefolius sample. | 1999 | 14 |

| PCR-RFLP | Three Panax species | 18S sequences | Based on the 18S rRNA gene, three Panax species gave species-specific electrophoretic profiles by PCR-RFLP and expected fragments corresponding to each species were detected only under defined conditions by mutant allele specific amplification (MASA, i.e. ARMS) analyses. | 1997 | 35 |

| PCR-RFLP | P. ginseng from four localities, one from China and three from Korea | 18S sequences | A ginseng sample showed fragments distinctive from the other two samples of the same country but different locality origins. | 2001 | 36 |

| AFLP | P. ginseng and P. quinquefolius | no | Polymorphic bands unique to P. ginseng and to P. quinquefolius and bands common to them were identified. P. ginseng samples from different farms in China and Korea are homogeneous genetically. P. quinquefolius from different sources are much more heterogeneous. | 2002 | 42 |

| RAPD | P. ginseng from four localities, one from China and three from Korea | no | Similarity among the DNA of ginseng plants analyzed was low. | 2001 | 36 |

| RAPD | Three strains of P. ginseng | no | A 725 bp band was present in the elite strain Aizu K-111 (now called Kaishusan) while the other strains did not always show this band. | 2001 | 62 |

| RAPD | Two cultivated groups of ginseng | no | Cluster analysis of the patterns showed that the genetic relationship between different strains of Da-maya group is closer than those strains of E-maya group. | 2004 | 64 |

| RAPD and AP-PCR | Three Panax species and adulterants | no | Fingerprints for P. ginseng or P. quinquefolius were basically consistent irrespective of plant source or age compared to the very different fingerprints from adulterants. The degree of similarity of the fingerprints confirmed that P. ginseng is more closely related to P. quinquefolius than it is to P. notoginseng. | 1995 | 52 |

| AP-PCR | Oriental ginseng from two sources and two American ginseng | no | Oriental ginseng from two sources produced nearly identical fingerprints. Two American ginseng samples gave fingerprints distinctive to the species with two primers tested but polymorphic and significantly different fingerprints with one of the primers tested. Therefore, the American ginseng samples were supposed to be from different strains. | 1994 | 60 |

| DALP | P. ginseng and P. quinquefolius | no | A DALP fragment was found present in all P. ginsengs but absent in all the P. quinquefolius examined. The species-specific band was converted to sequence-tagged site (i.e. amplification by specific primers giving a species-specific band) for quick authentication. | 2001 | 95 |

| DAMD | P. ginseng and P. quinquefolius | polymorphic AFLP band | A polymorphic AFLP band in P. ginseng contains a minisatellite which can be used in DAMD analysis to authenticate the two tested ginsengs. | 2002 | 42 |

| SCAR | Two Panax species and adulterants | polymorphic RAPD fragment | There is a 25 bp insertion in P. ginseng for a polymorphic RAPD fragment. By using primers designed based on this polymorphic fragment, P. quinquefolius and P. ginseng can be differentiated. Amplification on four other Panax species and two ginseng adulterants gave markedly different products. | 2001 | 91 |

| ARMS | Five Panax species and corresponding Ginseng drugs | trnK and nuclear 18S gene sequences | Five sets of species-specific primers with two pairs in each set were designed. Two expected fragments, one from trnK gene and another from 18S rRNA gene, were observed simultaneously only when the set of species-specific primers encountered template DNA of the corresponding species. | 2004 | 121 |

| SSR | Two Panax species | primer sequences for the loci | Using nine of the 16 screened loci, Chinese ginseng was differentiated unambiguously from the American samples. Some of the informative loci showed different allelic patterns among ginsengs from different farms. | 2003 | 25 |

| SSR | American ginseng and Oriental ginseng, cultivated and wild American ginseng | primer sequences for the loci | American ginseng had a different allele pattern (allele frequency in an American ginseng population of 34 cultivated and 21 wild ginseng) in two microsatellite loci compared with that of the Oriental ginseng (six from China and South Korea). Cultivated and wild American ginseng were distinguished. | 2005 | 141 |

| Sequencing | Three Panax species | primer sequences for 18S region | The sequences of the 18S rRNA region of 3 Panax species have different base substitutions at four nucleotide positions. By the polymorphism, the ginseng species from commercial samples were identified. | 1996 | 186 |

| Sequencing | Twelve Panax species | primer sequences for ITS and 5.8S regions | The sequences of the ITS and 5.8S coding region were used to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships among twelve Panax species. P. quinquefolius was suggested to be more closely related to the eastern Asian species than P. trifolius. Previous suggestions about monophyly of P. ginseng, P. notoginseng and P. quinquefolius were not supported by the ITS data. Several biogeographical implications were inferred from the results. | 1996 | 187 |

| Sequencing | Panax notoginseng of different cultivar origins | primer sequences for 18S and matK genes | The nuclear 18S rRNA and chloroplast matK genes of 18 samples of Panax notoginseng and its processed material Sanqi (Radix Notoginseng) were found to be identical regardless of cultivar origin. Thus the same strain should be used in cultivation for conservation of the species. | 2006 | 188 |

| Sequencing | P. notoginseng and adulterants | primer sequences for 18S and matK genes | Notoginseng and its adulterants were differentiated on the basis of their sequence variation in the nuclear ribosomal RNA small subunit (18S rRNA) and chloroplast matK gene. | 2001 | 67 |

| Sequencing | Two Panax species and adulterants | primer sequences for ITS and rbcL genes | The nuclear ITS and chloroplast rbcL regions were amplified using universal primers and then sequenced using nested ginseng-specific primers. All the samples including five root samples, thirteen powder samples and six capsule samples were identified as American or Korean ginseng except a capsule and a tablet that were identified as soybean, by using the universal primers for sequencing. They could not be sequenced by the nested primers. | 2000 | 174 |

The results obtained from Panax do not represent Chinese medicines. The results of specific techniques depend on their conditions (e.g. primers and magnesium concentration).

Conclusion

Authentication of Chinese medicinal materials is important for ensuring safe and appropriate use of Chinese medicines, ensuring the therapeutic effectiveness, minimizing unfair trade and raising consumers' confidence towards Chinese medicines. It also plays an important role in the modernization, industrialization and internationalization of Chinese medicine. DNA methods are reliable approaches towards authentication of Chinese medicinal materials. While their abilities in identification at various levels (e.g. species, strain and locality levels) may vary, they are used in identification of samples in any physical forms and provide consistent results irrespective of age, tissue origin, physiological conditions, environmental factors, harvest, storage and processing methods of the samples. The low requirement of sample quantity for analysis is of particular importance for quality control of premium medicinal materials and for detecting contaminants. For future development, it is necessary to compile a reference library of Chinese medicines with genetic information, especially for endangered species and those with high market value and/or with possible poisonous adulterants [243].

Abbreviations

5S spacer 5S rRNA gene spacer

18S gene a gene encoding for the small ribosomal subunit

26S gene a gene encoding for the large ribosomal subunit

AFLP amplified fragment length polymorphism

AP-PCR arbitrarily primed PCR

ARMS amplification refractory mutation system

AS-PCR allele-specific PCR

atpβ gene encoding the β-subunit of ATP synthase

atpβ-rbcL intergenic spacer the spacer region between the atpβ and rbcL genes

BSA bovine serum albumin

cyt b cytochrome b gene

DAF DNA amplification fingerprinting

DALP direct amplification of length polymorphism

DAMD directed amplification of minisatellite-region DNA

ISSR inter-simple sequence repeat

ITS internal transcribed spacer

matK gene encoding a putative maturase for splicing the precursor of trnK

ndhF gene encoding the ND5 protein of chloroplast NADH dehydrogenase

PCR polymerase chain reaction

PCR-RFLP PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism

RAPD random amplified polymorphic DNA

rbcL gene encoding large subunit of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase

rDNA ribosomal DNA

RP-PCR random-primed PCR

rRNA genes ribosomal RNA genes

SCAR sequence characterized amplified regions

SSLP simple sequence length polymorphism

SSR simple sequence repeat

STMS sequence-tagged microsatellite sites

trnK chloroplast transfer RNA (tRNA) gene for lysine

trnL – trnF spacer non-coding intergenic spacer between trnL and trnF in the chloroplast genome

trnL intron intron region between the two exons of tRNA gene for leucine

VNTR variable number of tandem repeat

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PYY drafted the manuscript. CFC, CYM and HSK helped draft and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The Astragalus samples were supplied by The School of Chinese Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Contributor Information

Pui Ying Yip, Email: hkanna2-paper@yahoo.com.hk.

Chi Fai Chau, Email: chaucf@nchu.edu.tw.

Chun Yin Mak, Email: cymak@govtlab.gov.hk.

Hoi Shan Kwan, Email: hoishankwan@cuhk.edu.hk.

References

- Coon JT, Ernst E. Complementary and alternative therapies in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2004;40:491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X, Sucher NJ. Stroke therapy in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM): prospects for drug discovery and development. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:478–484. doi: 10.1078/09447110260571760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marian F, Widmer M, Herren S, Donges A, Busato A. Physicians' philosophy of care: a comparison of complementary and conventional medicine. Forsch Komplementarmed. 2006;13:70–77. doi: 10.1159/000090735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahady GB. Global harmonization of herbal health claims. J Nutr. 2001;131:1120S–1123S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.1120S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh HL, Woo SO. Chinese proprietary medicine in Singapore: regulatory control of toxic heavy metals and undeclared drugs. Drug Saf. 2000;23:351–362. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200023050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- But PP, Tomlinson B, Cheung KO, Yong SP, Szeto ML, Lee CK. Adulterants of herbal products can cause poisoning. BMJ. 1996;313:117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7049.117a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HH, Yen DHT, Wu ML, Deng JF, Huang CI, Lee CH. Acute Erycibe henryi Prain ("Ting Kung Teng") poisoning. Clin Toxicol. 2006;44:71–75. doi: 10.1080/15563650500394902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaneberg BT, Khan IA. Analysis of products suspected of containing Aristolochia or Asarum species. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;94:245–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Chen L, An Z, Shi S, Zhan Y. Non-technical causes of fakes existing in Chinese medicinal material markets. Zhongyaocai. 2002;25:516–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YQ, Wang N, Zhou H, Qu LH. Differentiation of medicinal Cordyceps species by rDNA ITS sequence analysis. Planta Med. 2002;68:635–639. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XQ, Zhu DY, Li SP, Dong TT, Tsim KW. Authentic identification of stigma Croci (stigma of Crocus sativus) from its adulterants by molecular genetic analysis. Planta Med. 2001;67:183–186. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-11533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YP. Toxicity of the Chinese herb mu tong (Aristolochia manshuriensis). What history tells us. Adverse Drug React Toxicol Rev. 2002;21:171–177. doi: 10.1007/BF03256194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan ST. Consideration on the problem of "ascension of the case poisoned by Chinese Traditional Medicines". Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2000;25:579–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngan F, Shaw P, But P, Wang J. Molecular authentication of Panax species. Phytochemistry. 1999;50:787–791. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(98)00606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong TT, Cui XM, Song ZH, Zhao KJ, Ji ZN, Lo CK, Tsim KW. Chemical assessment of roots of Panax notoginseng in China: regional and seasonal variations in its active constituents. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:4617–4623. doi: 10.1021/jf034229k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YB, Ngan FN, Wang ZT, Ng TB, But PPH, Shaw PC, Wang J. Random primed polymerase chain reaction differentiates Codonopsis pilosula from different localities. Planta Med. 1999;65:157–160. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-14058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Cui Z, Liu Y, Wang D, Liu N, Yoshikawa M. Quality evaluation of traditional Chinese drug toad venom from different origins through a simultaneous determination of bufogenins and indole alkaloids by HPLC. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2005;53:1582–1586. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HT, Hu SL, Guo BL, Feng XF, Yan YN, Li JS. A study on genetic variation between wild and cultivated populations of Paeonia lactiflora Pall. Yaoxue Xuebao. 2002;37:383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XQ, Shi Q, Duan JA, Dong TT, Tsim KW. Chemical analysis of Radix Astragali (Huangqi) in China: a comparison with its adulterants and seasonal variations. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:4861–4866. doi: 10.1021/jf0202279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Feo V, Bruno M, Tahiri B, Napolitano F, Senatore F. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oils from Thymus spinulosus Ten. (Lamiaceae) J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:3849–3853. doi: 10.1021/jf021232f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira AC, Richter T, Bennetzen JL. Regional and racial specificities in sorghum germplasm assessed with DNA markers. Genome. 1996;39:579–587. doi: 10.1139/g96-073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denke A, Schempp H, Mann E, Schneider W, Elstner EF. Biochemical activities of extracts from Hypericum perforatum L. 4th Communication: influence of different cultivation methods. Arzneimittelforschung. 1999;49:120–125. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1300371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WT, Thissen U, Ehlert KA, Koek MM, Jellema RH, Hankemeier T, van der Greef J, Wang M. Effects of growth conditions and processing on Rehmannia glutinosa using fingerprint strategy. Planta Med. 2006;72:458–467. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo BL, Basang D, Xiao PG, Hong DY. Research on the quality of original plants and material medicine of Cortex Paeoniae. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2002;27:654–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hon CC, Chow YC, Zeng FY, Leung FC. Genetic authentication of ginseng and other traditional Chinese medicine. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2003;24:841–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XD, Su ZR, Lai XP, Lin SH, Dong XB, Liu ZQ, Xie PS. Changes of dehydroandrographolide's contents of andrographis tablet in the process of production. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2002;27:911–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GH. Effect of processing on essential components of Raphnus sativus L. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 1993;18:89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZL, Song ZQ, Zhang L, Li SL. Influence of process methods on contents of chemical component Radix Polygoni Multiflori. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2005;30:336–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Cao L, Meng XC, Wang XJ. Studies on the method for the processing roots of cultivated Saposhnikovia divaricata. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2003;28:402–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian YH, Jin FY, Lei H. Effects of processing on contents of saccharides in huangqi. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2003;28:128–129. 173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZM, You LS, Jiang X, Li L, Wang WH, Wang G. Methodological studies on selectively removing toxins in Aristolochiae manshuriensis by chinese processing techniques. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2005;30:1243–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K. Some aspects of toxic contaminants in herbal medicines. Chemosphere. 2003;52:1361–1371. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YP, Cao H, Komatsu K, But PP. Quality control for Chinese herbal drugs using DNA probe technology. Yaoxue Xuebao. 2001;36:475–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockley AK, Bardsley RG. DNA-based methods for food authentication. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2000;11:67–77. doi: 10.1016/S0924-2244(00)00049-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fushimi H, Komatsu K, Isobe M, Namba T. Application of PCR-RFLP and MASA analyses on 18S ribosomal RNA gene sequence for the identification of three Ginseng drugs. Biol Pharm Bull. 1997;20:765–769. doi: 10.1248/bpb.20.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Um JY, Chung HS, Kim MS, Na HJ, Kwon HJ, Kim JJ, Lee KM, Lee SJ, Lim JP, Do KR, Hwang WJ, Lyu YS, An NH, Kim HM. Molecular authentication of Panax ginseng species by RAPD analysis and PCR-RFLP. Biol Pharm Bull. 2001;24:872–875. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CZ, Li P, Ding JY, Jin GQ, Yuan CS. Identification of Fritillaria pallidiflora using diagnostic PCR and PCR-RFLP based on nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer sequences. Planta Med. 2005;71:384–386. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-864112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami H, Okabe Y, Kohda H, Hiraoka N. Identification of the crude drug atractylodes rhizome (Byaku-jutsu) and atractylodes lancea rhizome (So-jutsu) using chloroplast TrnK sequence as a molecular marker. Biol Pharm Bull. 2000;23:589–594. doi: 10.1248/bpb.23.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu RZ, Wang J, Zhang YB, Wang ZT, But PP, Li N, Shaw PC. Differentiation of medicinal Codonopsis species from adulterants by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism. Planta Med. 1999;65:648–650. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-14091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbo EC, Majiwa PA, Claassen EJ, Roos MH. Measure of molecular diversity within the Trypanosoma brucei subspecies Trypanosoma brucei brucei and Trypanosoma brucei gambiense as revealed by genotypic characterization. Exp Parasitol. 2001;99:123–131. doi: 10.1006/expr.2001.4666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos P, Hogers R, Bleeker M, Reijans M, van de Lee T, Hornes M, Frijters A, Pot J, Peleman J, Kuiper M. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha WY, Shaw PC, Liu J, Yau FC, Wang J. Authentication of Panax ginseng and Panax quinquefolius using amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) and directed amplification of minisatellite region DNA (DAMD) J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:1871–1875. doi: 10.1021/jf011365l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datwyler SL, Weiblen GD. Genetic variation in hemp and marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) according to amplified fragment length polymorphisms. J Forensic Sci. 2006;51:371–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong DY, Lau AJ, Yeo CL, Liu XK, Yang CR, Koh HL, Hong Y. Genetic diversity and variation of saponin contents in Panax notoginseng roots from a single farm. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:8460–8467. doi: 10.1021/jf051248g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan M, Hong Y. Heterogeneity of Chinese medical herbs in Singapore assessed by fluorescence AFLP analysis. Am J Chin Med. 2003;31:773–779. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X03001351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Huang BB, Kai GY, Guo ML. Analysis of intraspecific variation of Chinese Carthamus tinctorius L. using AFLP markers. Yaoxue Xuebao. 2006;41:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh JP, Kiew R, Kee A, Gan LH, Gan YY. Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) provides molecular markers for the identification of Caladium bicolor cultivars. Ann Bot (Lond) 1999;84:155–161. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1999.0903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desmarais E, Lanneluc I, Lagnel J. Direct amplification of length polymorphisms (DALP), or how to get and characterize new genetic markers in many species. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1458–1465. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.6.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JR, Fuller JD, Macaulay M, Hatz BG, Jahoor A, Powell W, Waugh R. Direct comparison of levels of genetic variation among barley accessions detected by RFLPs, AFLPs, SSRs and RAPDs. Theor Appl Genet. 1997;95:714–722. doi: 10.1007/s001220050617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vos P, Kuiper M. AFLP analysis. In: Caetano-Anollés G, Gresshoff PM, editor. DNA markers: protocols, applications, and overviews. New York Wiley-Liss; 1997. pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, But PP, Shaw PC. Authentication of the Chinese drug "ku-di-dan" (herba elephantopi) and its substitutes using random-primed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) Yaoxue Xuebao. 1996;31:543–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PC, But PP. Authentication of Panax species and their adulterants by random-primed polymerase chain reaction. Planta Med. 1995;61:466–469. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-958138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip PY, Kwan HS. Molecular identification of Astragalus membranaceus at the species and locality levels. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;106:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau DT, Shaw PC, Wang J, But PP. Authentication of medicinal Dendrobium species by the internal transcribed spacer of ribosomal DNA. Planta Med. 2001;67:456–460. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-15818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh J, McClelland M. Fingerprinting genomes using PCR with arbitrary primers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:7213–7218. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JG, Kubelik AR, Livak KJ, Rafalski JA, Tingey SV. DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6531–6535. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano-Anolles G, Bassam BJ, Gresshoff PM. DNA amplification fingerprinting using very short arbitrary oligonucleotide primers. Biotechnology (N Y) 1991;9:553–557. doi: 10.1038/nbt0691-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez P, Dorado G, Ramirez MC, Laurie DA, Snape JW, Martin A. Development of cost-effective Hordeum chilense DNA markers: molecular aids for marker-assisted cereal breeding. Hereditas. 2003;138:54–58. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5223.2003.01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JL, Huang LQ, Shao AJ, Lin SF. RAPD analysis on different varieties of Rehmannia glutinosa. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2002;27:505–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung KS, Kwan HS, But PP, Shaw PC. Pharmacognostical identification of American and Oriental ginseng roots by genomic fingerprinting using arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction (AP-PCR) J Ethnopharmacol. 1994;42:67–69. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan HS, Chiu SW, Pang KM, Cheng SC. Strain typing in Lentinula edodes by polymerase chain reaction. Exp Mycol. 1992;16:163–166. doi: 10.1016/0147-5975(92)90023-K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tochika-Komatsu Y, Asaka I, Ii I. A random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) primer to assist the identification of a selected strain, aizu K-111 of Panax ginseng and the sequence amplified. Biol Pharm Bull. 2001;24:1210–1213. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding G, Ding XY, Shen J, Tang F, Liu DY, He J, Li XX, Chu BH. Genetic diversity and molecular authentication of wild populations of Dendrobium officinale by RAPD. Yaoxue Xuebao. 2005;40:1028–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao AJ, Li X, Huang LQ, Wei JH, Lin SF. Genetic analysis of cultivated ginseng population with the assistance of RAPD technology. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2004;29:1033–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista NS, Solis R, Kamijima O, Ishii T. RAPD, RFLP and SSLP analyses of phylogenetic relationships between cultivated and wild species of rice. Genes Genet Syst. 2001;76:71–79. doi: 10.1266/ggs.76.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Liang H, Sun Y, Yan Q, Zhang X. Identification of somatic hybrids between rice cultivar and wild Oryza species by RAPD. Chin J Biotechnol. 1996;12:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Liu Y, Fushimi , Komatsu K. Identification of notoginseng (Panax notoginseng) and its adulterants using DNA sequencing. Zhongyaocai. 2001;24:398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LQ, Wang M, Yang B, Gu HY. Authentication of the Chinese drug Tian-hua-fen (Radix Trichosanthes) and its adulterants and substitutes using Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) Chin J Pharm Anal. 1999;19:233. [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Su Y, Zhu J, Li X, Zeng O, Xia N. Studies on DNA amplification fingerprinting of cortex Magnoliae officinalis. Zhongyaocai. 2001;24:710–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong TT, Ma XQ, Clarke C, Song ZH, Ji ZN, Lo CK, Tsim KW. Phylogeny of Astragalus in China: molecular evidence from the DNA sequences of 5S rRNA spacer, ITS, and 18S rRNA. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:6709–6714. doi: 10.1021/jf034278x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Terefework Z, Chen W, Lindstrom K. Genetic diversity of rhizobia isolated from Astragalus adsurgens growing in different geographical regions of China. J Biotechnol. 2001;91:155–168. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(01)00337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paran I, Michelmore RW. Development of reliable PCR-based markers linked to downy mildew resistance genes in lettuce. Theor Appl Genet. 1993;85:985–993. doi: 10.1007/BF00215038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasco OP, Graham GC, Henry RJ, Adkins SW, Smith MK, Godwin ID. Random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) detection of dwarf off-types in micropropagated Cavendish (Musa spp AAA) bananas. Plant Cell Rep. 1996;16:118–123. doi: 10.1007/BF01275464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos KM, Gale MD. The use of random amplified polymorphic DNA markers in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 1992;84:567–572. doi: 10.1007/BF00224153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez T, Albornoz J, Dominguez A. An evaluation of RAPD fragment reproducibility and nature. Mol Ecol. 1998;7:1347–1357. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano-Anolles G. DAF optimization using Taguchi methods and the effect of thermal cycling parameters on DNA amplification. Biotechniques. 1998;25:472–476. doi: 10.2144/98253rr03. 478–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff K, Schoen ED, Petersvanrijn J. Optimizing the generation of random amplified polymorphic DNAs in chrysanthemum. Theor Appl Genet. 1993;86:1033–1037. doi: 10.1007/BF00211058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya E, Ranade SA. Molecular distinction amongst varieties of mulberry using RAPD and DAMD profiles. BMC Plant Biol. 2001;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlenbacher SA, Brown RN, Davis JW, Chen H, Bassil NV, Smith DC, Kubisiak TL. RAPD markers linked to eastern filbert blight resistance in Corylus avellana. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;108:651–656. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1476-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian W, Ge S, Hong DY. Genetic variation within and among populations of a wild rice Oryza granulata from China detected by RAPD and ISSR markers. Theor Appl Genet. 2001;102:440–449. doi: 10.1007/s001220051665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ronimus RS, Parker LE, Morgan HW. The utilization of RAPD-PCR for identifying thermophilic and mesophilic Bacillus species. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;147:75–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YH, Negre S. Use of glycerol for enhanced efficiency and specificity of PCR amplification. Trends Genet. 1993;9:297. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90238-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schierwater B, Ender A. Different thermostable DNA polymerases may amplify different RAPD products. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4647–4648. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.19.4647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Lankhorst RM, Vermunt A, Weide R, Zabel P. Isolation of molecular markers for tomato (L. esculentum) using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) Theor Appl Genet. 1991;83:108–114. doi: 10.1007/BF00229232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobral BWS, Honeycutt RJ. High output genetic mapping of polyploids using PCR-generated markers. Theor Appl Genet. 1993;86:105–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00223814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheli MR, Bova R, Pascale E, D'Ambrosio E. Reproducible DNA fingerprinting with the random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) method. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1921–1922. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.10.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JG, Reiter RS, Young RM, Scolnik PA. Genetic mapping of mutations using phenotypic pools and mapped RAPD markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2697–2702. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.11.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland M, Welsh J. DNA fingerprinting by arbitrarily primed PCR. PCR Methods Appl. 1994;4:S59–65. doi: 10.1101/gr.4.1.s59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreader CA. Relief of amplification inhibition in PCR with bovine serum albumin or T4 gene 32 protein. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1102–1106. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.1102-1106.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stommel JR, Panta GR, Levi A, Rowland LJ. Effects of gelatin and BSA on the amplification reaction for generating RAPD. Biotechniques. 1997;22:1064–1066. doi: 10.2144/97226bm11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ha WY, Ngan FN, But PP, Shaw PC. Application of sequence characterized amplified region (SCAR) analysis to authenticate Panax species and their adulterants. Planta Med. 2001;67:781–783. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh J, Ralph D, McClelland M. DNA and RNA fingerprinting using arbitrarily primed PCR. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, editor. PCR Strategies. San Diego: Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kostia S, Palo J, Varvio SL. DNA sequences of RAPD fragments in artiodactyls. Genome. 1996;39:456–458. doi: 10.1139/g96-057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Wang Y, Lei G, Xu R, Painter J. Genetic differentiation within metapopulations of Euphydryas aurinia and Melitaea phoebe in China. Biochem Genet. 2003;41:107–118. doi: 10.1023/A:1022078017952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha WY, Yau FC, But PP, Wang J, Shaw PC. Direct amplification of length polymorphism analysis differentiates Panax ginseng from P. quinquefolius. Planta Med. 2001;67:587–589. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langar K, Lorieux M, Desmarais E, Griveau Y, Gentzbittel L, Berville A. Combined mapping of DALP and AFLP markers in cultivated sunflower using F9 recombinant inbred lines. Theor Appl Genet. 2003;106:1068–1074. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha WY, Yau FCF, Wang J, Shaw PC. Differentiation of Panax ginseng from P. quinquefolius by Direct Amplification of Length Polymorphisms. In: Shaw PC, Wang J, But PPH, editor. Authentication of Chinese medicinal materials by DNA technology. Singapore: World Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zietkiewicz E, Rafalski A, Labuda D. Genome fingerprinting by simple sequence repeat (SSR)-anchored polymerase chain reaction amplification. Genomics. 1994;20:176–183. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira RL, Carvalho OS, Lage RC, Cardoso PC, Oliveira GC. Sequencing of simple sequence repeat anchored polymerase chain reaction amplification products of Biomphalaria glabrata. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:23–26. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000900006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souframanien J, Gopalakrishna T. A comparative analysis of genetic diversity in blackgram genotypes using RAPD and ISSR markers. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;109:1687–1693. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1797-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakoczy-Trojanowska M, Bolibok H. Characteristics and a comparison of three classes of microsatellite-based markers and their application in plants. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2004;9:221–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Ding X, Liu D, Ding G, He J, Li X, Tang F, Chu B. Intersimple sequence repeats (ISSR) molecular fingerprinting markers for authenticating populations of Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:420–422. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan MZ, Bornet B, Balatti PA, Branchard M. Inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers as a tool for the assessment of both genetic diversity and gene pool origin in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Euphytica. 2003;132:297–301. doi: 10.1023/A:1025032622411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo WL, Gong L, Ding ZF, Li YD, Li FX, Zhao SP, Liu B. Genomic instability in phenotypically normal regenerants of medicinal plant Codonopsis lanceolata Benth. et Hook. f., as revealed by ISSR and RAPD markers. Plant Cell Rep. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tian C, Nan P, Shi S, Chen J, Zhong Y. Molecular genetic variation in Chinese populations of three subspecies of Hippophae rhamnoides. Biochem Genet. 2004;42:259–267. doi: 10.1023/B:BIGI.0000034430.93055.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Zheng YL, Chen L, Wei YM, Yang RW, Yan ZH. Evaluation of genetic relationships in the genus Houttuynia Thunb. in China based on RAPD and ISSR markers. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2005;33:1141–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.bse.2005.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DB, Schlötterer C, (Eds) Microsatellites: Evolution and Applications. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Heath DD, Iwama GK, Devlin RH. PCR primed with VNTR core sequences yields species specific patterns and hypervariable probes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5782–5785. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.24.5782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers DJ, Demmon G. Identification of repetitive, genome-specific probes in crucifer oilseed species. Genome. 2002;45:485–492. doi: 10.1139/g02-006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva LM, Montes de Oca H, Diniz CR, Fortes-Dias CL. Fingerprinting of cell lines by directed amplification of minisatellite-region DNA (DAMD) Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34:1405–1410. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2001001100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroso G, Sonnenberg AS, Van Griensven LJ, Labarere J. Molecular cloning of a widely distributed microsatellite core sequence from the cultivated mushroom Agaricus bisporus. Fungal Genet Biol. 2000;31:115–123. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2000.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MY, Doh EJ, Park CH, Kim YH, Kim ES, Ko BS, Oh SE. Development of SCAR marker for discrimination of Artemisia princeps and A. argyi from other Artemisia herbs. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:629–633. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]