Abstract

Background and purpose:

This study investigated whether stimulation of cannabinoid receptors influences smooth muscle contractility in the rat prostate gland.

Experimental approach:

Immunohistochemistry was used to characterize and localize cannabinoid receptors in the rat prostate gland. Isolated organ bath experiments were carried out to investigate the effects of cannabinoids on prostate contractility.

Key results:

Immunohistochemical studies of the rat prostate yielded positive immunoreactivity for the CB1 receptor, but not the CB2 receptor. Double labelling revealed that CB1 receptors were not colocalized with α-actin in the smooth muscle layer but were primarily expressed within the epithelial lining of the prostatic acini. The cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 (10 nM – 10 μM) inhibited contractile responses to electrical-field stimulation (10 Hz, 0.5 ms, 60 V for 2 s per minute) in a concentration-dependent manner. The CB1 selective antagonists, SR141716 (1 μM) and LY 320135 (1 μM), reversed the WIN 55,212-2-mediated inhibition but the CB2 selective antagonist, SR144528 (1 μM), did not. Furthermore, the cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin (0.1 μM) caused significant reversal of the WIN 55,212-2 mediated inhibition of contractile responses, whereas the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor N ω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-NAME, 1 mM) did not. Prostaglandin E2 (10 nM – 10 μM), produced a similar concentration-dependent inhibition to WIN 55,212-2.

Conclusions and implications:

WIN 55,212-2, an agonist at cannabinoid receptors, causes inhibition of smooth muscle contraction in the rat prostate by activating epithelial CB1 receptors. This inhibition is mediated via the cyclooxygenase pathway.

Keywords: cannabinoids; rat prostate; epithelial cells; WIN 55,212-2; smooth muscle; cyclooxygenase and prostaglandin

Introduction

In all mammals the prostate gland surrounds the proximal urethra just inferior to the urinary bladder. Enclosed within its capsule is a complex series of ducts that form a glandular structure that provides proteins that constitute part of the ejaculatory fluid (Lee et al., 1990). These ducts are lined with mainly columnar epithelial cells that separate the lumen from an underlying stromal matrix (Jesik et al., 1982). Like other mammals, the stromal matrix of the rat prostate gland incorporates smooth muscle, which is sympathetically innervated (Flickinger, 1972). Release of noradrenaline and adenosine 5′-trisphosphate (ATP) from sympathetic nerve terminals causes contraction of the rat prostatic smooth muscle to propel prostatic secretions into the urethra during ejaculation (Ventura et al., 2003).

Cannabinoid receptors are G-protein-coupled receptors that recognize cannabinoid ligands and are denoted by the abbreviation CB (Howlett et al., 2002). To date, two cannabinoid receptor subtypes have been cloned, the CB1 and CB2 receptor (Matsuda et al., 1990; Munro et al., 1993). The difference between the two receptors is based on predicted amino-acid sequences, signalling mechanisms and their tissue distribution (Howlett et al., 2002). It has been shown that the CB1 receptor, which is predominantly found in the central nervous system, is expressed in peripheral tissues including the male reproductive tract (Ruiz-Llorente et al., 2003). Cannabinoids are capable of eliciting an effect on reproductive organs through either direct or indirect mechanisms (Purohit et al., 1980; Murphy et al., 1998). Although the presence of endocannabinoids has not been shown in the prostate, CB1 receptor expression has been shown in the epithelial cell layer of the human prostate (Ruiz-Llorente et al., 2003). Furthermore an anandamide uptake transporter and the enzyme responsible for endocannabinoid degradation, fatty acid amidohydrolase (FAAH), are expressed in human prostate (Ruiz-Llorente et al., 2004). Research in the area has focused on the ability of cannabinoids to influence cellular proliferation using epithelial cell lines. However, epithelial and stromal tissue layers, such as are found in the prostate, are able to interact and communicate molecular instructions (Hayward, 2002). This suggests that CB receptors may influence prostatic contractility.

Increasing evidence suggests that cannabinoids are able to affect smooth muscle contractility through a number of different mechanisms at different sites in the body. Peripheral CB1 receptors have been shown to inhibit electrically stimulated contractions in the rat vas deferens presynaptically (Christopoulos et al., 2001), presumably through the inhibition of noradrenaline release from presynaptic nerve terminals (Ishac et al., 1996). Prejunctional CB1 receptors are also involved in presynaptic neurotransmission in other peripheral tissues such as the guinea-pig ileum (Izzo et al., 1998) and the mouse urinary bladder (Pertwee and Fernando, 1996). The ability of cannabinoids to influence contractility is also seen in blood vessels, where cannabinoids are capable of causing endothelial dependent or independent smooth muscle relaxation (Deutsch et al., 1997; Ho and Hiley, 2003).

The aims of this study were to investigate whether cannabinoids are capable of influencing electrically evoked contractions of the rat prostate and to characterize the mechanism of action of any observed effect.

Methods

Animals and tissues

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (200–300 g) were housed in a controlled environment at 22°C and exposed to a photoperiod of 12 h light and 12 h dark. Animals were allowed access to food and water ad libitum. Rats were killed by cervical dislocation. Abdominal incisions were made exposing the male urogenital region of the rat. Testes were then repositioned to the left and right to allow ease of access while dissecting out the lobes of the prostate. Each rat provided two prostatic preparations from the left and right lobes of the prostate thus providing internal controls for contractile experiments. Ethics approval was obtained from the Monash University Standing Committee of Animal Ethics in Animal Experimentation (Ethics no. VCPA 2003/05).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue preparation

Dissected prostate lobes were placed in a fixative solution consisting of 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; mM; NaCl 137.0, KCl 3.0, KH2PO4 2.0, Na2HPO4 8.0; pH=7.4) for 2 h at room temperature. Tissues were subsequently washed four times for 10 min in PBS containing 7% sucrose and 0.01% sodium azide and cryoprotected in this solution for 48 h at 4°C. Tissues were then placed in Tissue TEK (OCT embedding compound) in plastic moulds, snap frozen using iso-pentane cooled in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Frozen 12 μM tissue sections were cut using a Leica CM1850 cryostat at −20°C and thawed onto gelatin-coated slides. Slide-mounted sections were allowed to air dry for 1 h.

Single labelling

Slide-mounted sections were incubated for 18–20 h in a moist chamber at room temperature with a rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:200) targeting the CB1 or CB2 receptor (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). A PBS medium containing 0.1% w/v sodium azide, 0.01% w/v bovine serum albumin, 0.1% w/v lysine and 0.1% v/v Triton was used for all antibody dilutions. Tissue sections were subsequently washed in PBS four times for 10 min and incubated with fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC) tagged anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were again washed in PBS four times for 10 min and then a coverslip was applied using the fluorescence preserving mounting medium, Vectashield (Vector). In all studies, background levels of fluorescence were determined by comparison with negative controls that excluded the primary antibody from the diluting medium. Sections were viewed with an Olympus BX60 fluorescence microscope fitted with an Olympus U-MWB filter cube. Immunofluorescent micrographs were taken using a SPOT RT230 Slider Digital Camera and processed using SPOT RT software v3.1 run on a Compaq personal computer.

Double labelling

Double labelling techniques were used to compare immunopositive staining with other structures in the rat prostate. Prostate sections were immunoprocessed by simultaneously incubating sections with the rabbit polyclonal antibody for the CB1 receptor (Cayman; 1:200) and a mouse monoclonal antibody for smooth muscle actin (DAKO; 1:250) for 18–20 h. Slides were then washed in PBS four times for 10 min.

A secondary simultaneous incubation period of 1 h was performed at room temperature with FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Vector; 1:250) and Texas Red-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Vector; 1:200). Sections were again washed with PBS four times at 10 min intervals and a coverslip applied using Vectashield (Vector). Immunoreactivity was visualized using an Olympus BX60 fluorescence microscope fitted with an Olympus U-MWB filter cube to visualize the immunofluorescent FITC tag and an Olympus U-MWIY filter cube to visualize the Texas Red staining. Immunofluorescent micrographs were taken using a SPOT RT230 Slider Digital Camera and processed using SPOT RT software v3.1 run on a Compaq personal computer.

Isolated organ bath studies

Organ bath setup

The connecting fascia of the rat prostate was bisected to provide left and right paired lobe preparations. Immediately following excision, prostates were placed into a Petri dish containing Krebs–Henseleit solution (mM: NaCl 118.1, KCl 4.69, KH2PO4 1.2, NaHCO3 25.0, glucose 11.7, MgSO4 0.5, CaCl2 2.5; pH=7.4) and the surrounding prostatic capsule along with excess fatty tissue was dissected away to facilitate drug distribution throughout the tissue. Prostates were mounted between two platinum electrodes embedded in a perspex tissue holder. One end of the prostate was attached to a static platinum hook embedded in the tissue holder which was subsequently suspended in a 10 ml jacketed organ bath filled with Krebs–Henseleit solution maintained at 37°C and bubbled with 95% O2:5% CO2. The other end of the prostate was attached to an isometric Grass FTO3 force transducer, which measured the force displacement caused by tissue contractility. A PowerLab data acquisition system transmitted information provided by the force transducer for recording on a Power Macintosh 5500/225 computer.

During the course of the experiment, preparations were maintained at a resting tension of 0.5–0.8 g. Tissues were initially equilibrated for a 60 min period where nerve terminals were stimulated by a Grass S88 stimulator via the parallel platinum electrodes incorporated in the perspex tissue holders. Electrical field stimulation parameters during equilibration were set to deliver repeated pulses of 0.5 ms duration, 60 V at 0.01 Hz over the 60 min period. The bath solution was replaced every 15 min during the equilibration period and as needed during experiments to avoid any sporadic disturbances caused by frothing from tissue secretions. All experiments were undertaken with a contralateral internal control where one tissue was treated with a blocking drug and the other with vehicle.

Concentration–response curves

Concentration–response curves were constructed to test the effect of the CB receptor agonist, WIN 55,212-2, in the rat prostate, on electrical field stimulation-induced contractions (parameters: 0.5 ms duration, 60 V, 10 Hz. Tissues were electrically stimulated with 2 s trains once every minute). Discrete additions of increasing concentrations (10 nM–10 μM) of WIN 55,212-2 were added to baths at half log unit increments. The mean of four contractile responses was taken from tissues at the end of a 10 min exposure and compared to contractile responses taken at the beginning of the experiment before the addition of the first concentration of agonist. Tissues were subsequently washed with four to five times the bath volume, and the next concentration was added after a further 10 min.

Receptor antagonists and enzyme inhibitors were added at the beginning of the incubation period, so that they were in contact with the isolated prostates for at least 60 min before the beginning of the concentration–response curves. All concentration–response curves were run in parallel with contralateral vehicle controls. Antagonists, inhibitors and vehicles were replaced after washes to maintain tissue contact for the duration of the experiment. The antagonists SR141716 (1 μM) and LY320135 (1 μM) were used to block CB1 receptors and SR144528 (1 μM) was used to block CB2 receptors. Concentrations used are at least five times greater than the published Ki values (Alexander et al., 2006) at these receptors. The enzyme inhibitors used were Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-NAME) (0.1–1 mM) and indomethacin (0.1 μM). We routinely use these concentrations in our laboratory to block nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase, respectively.

In a subset of experiments, isolated prostates were not stimulated and the effect of WIN 55,212-2 (1 or 10 μM) was tested on contractions mediated by exogenously administered noradrenaline (1 μM). Vehicle or WIN 55,212-2 (1 or 10 μM) was administered 10 min before noradrenaline (1 μM). Noradrenaline (1 μM) was administered at 10 min intervals.

Analysis of data

All measurements taken from experiments were of peak contractile force (g). Results from experiments were expressed as a percentage of initial contractile force taken before the addition of the first concentration of cannabinoid and subsequently analysed with repeated measures two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using GraphPad Prism 4.0. The interaction between concentration and treatment was used to evaluate statistical significance. Control responses in the absence or presence of blocking drugs before the addition of WIN 55,212-2 or prostaglandin E2 were compared using Student's paired t-tests. In all cases, values of P<0.05 were considered significant.

Drugs

Drugs used were indomethacin (from Sigma-Aldrich), L-NAME (from Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), LY320135 (6-methoxy-2-(methoxyphenyl)benzo[b][thien-3-yl][4-cyanophenyl]methanone; generous gift from Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, USA), Prostaglandin E2 (from Sigma-Aldrich), SR141716 (N-piperidino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-3-pyrazolecarboxa-mide); generous gift from Sanofi-Synthélabo Recherche, Montepellier, France), SR144528 (N-[1S)-endo-1,3,3-triemthyl bicyclo [2.2.1] heptan-2-yl]-5-(4-chloro-3-methylphenyl)-1-(4-methylbenzyl)-pyrazole-3-carboxamide; generous gift from Sanofi-Synthélabo Recherche, Montpellier, France), WIN 55,212-2 ((R)-(+)-[2,3-dihydro-5-methyl-3[(4-morpholinyl)methyl]pyrolol[1,2,3-de]-1,4-benzoxazinyl]-(1-napthalenyl)methanone mesylate; from Sigma-Aldrich). LY320135, SR141716, SR144528 and WIN 55,212-2 were dissolved using DMSO. Indomethacin was dissolved using ethanol. L-NAME and prostaglandin E2 were dissolved using distilled water. All dilutions to the required concentrations were made in distilled water. The maximum volume of vehicle or drug added to the 10 ml organ baths was 100 μl.

Results

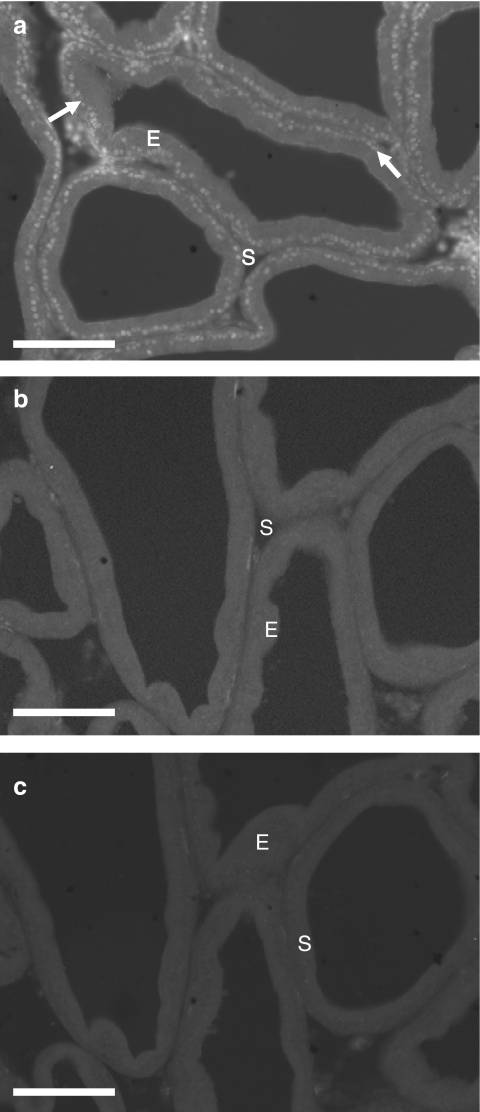

Immunofluorescence

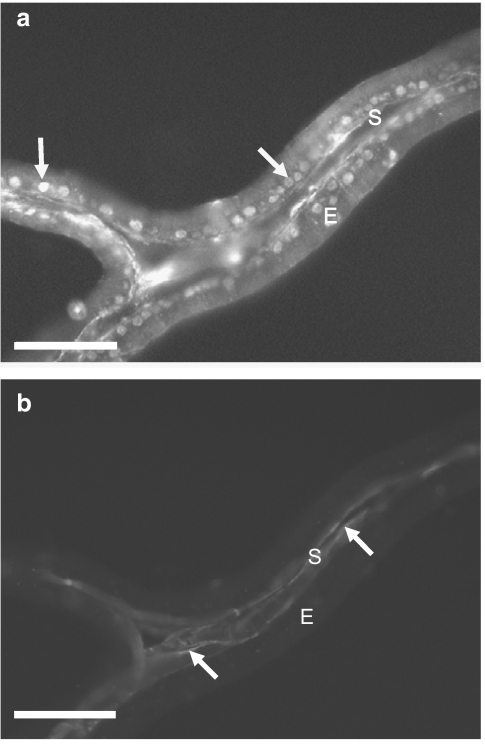

When the primary antibody was excluded from the diluting medium for the purpose of all negative controls no immunoreactivity was observed (Figure 1c). Similarly, no immunoreactivity for the CB2 receptor was seen in either the prostatic epithelium or the fibromuscular stroma (Figure 1b). CB1 receptor immunoreactivity was observed throughout the prostatic epithelium and the most intense staining appeared to be in the centre of the cells, correlating to the epithelial nuclei, and to a lesser extent in the region of the basal membrane (Figure 1a). Double-labelled sections of tissue stained for both the CB1 receptor (Figure 2a) and smooth muscle actin (Figure 2b), confirming that the CB1 receptor was not expressed within the smooth muscle layer, but in the epithelial layer surrounding the prostatic acini.

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescent photomicrographs of fixed, frozen 12 μm sections of rat prostate. (a) Tissue incubated with antibodies for the CB1 receptor. (b) Tissue incubated with antibodies for the CB2 receptor. (c) Negative control incubated without primary antibodies present. White arrows indicate positive staining, E (epithelial layer) and S (stromal layer). Calibration bars indicate 100 μm.

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescent photomicrographs of fixed, frozen 12 μm section of rat prostate double labelling with: antibodies for the CB1 receptor (a) and antibodies for smooth muscle α-actin (b). White arrows indicate positive staining, E (epithelial layer) and S (stromal layer). Calibration bars indicate 50 μm.

Isolated organ bath studies

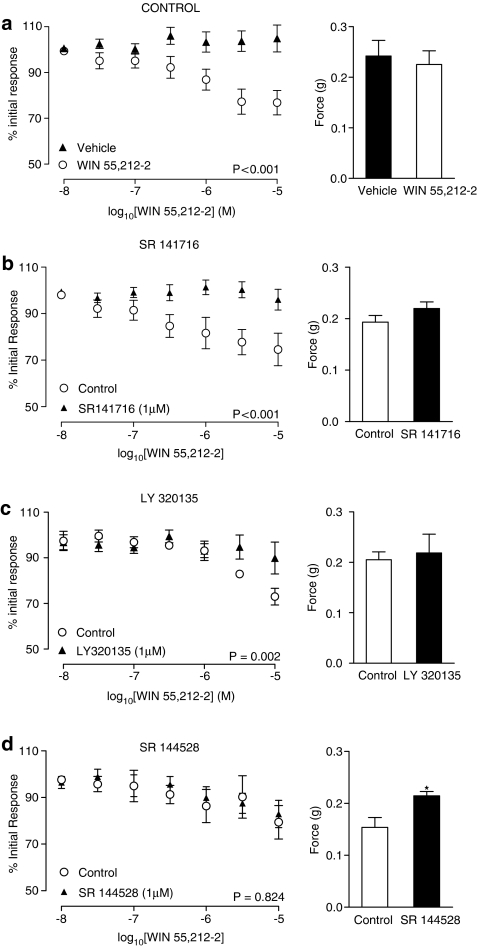

Responses to electrical field stimulation (0.5 ms, 60 V, 10 Hz) were inhibited by the synthetic cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 (10 nM–10 μM) in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3a; P<0.001, n=6). Inhibition was blocked by the CB1 selective antagonists SR141716 (1 μM, P<0.001, n=6) and LY320135 (1 μM, P=0.002, n=6) (Figure 3b and c, respectively). The CB2 selective antagonist SR144528 (1 μM) had no effect on the WIN55,212-2-mediated inhibition (Figure 3d; P=0.824, n=6).

Figure 3.

Mean inhibitory log concentration–response curves for WIN 55,212-2 in the presence and absence of any agonist or antagonist (a), in the presence and absence of the CB1 receptor antagonists SR 141716 (1 μM) (b) and LY 320135 (1 μM) (c), and in the presence and absence of the CB2 receptor antagonist SR 144528 (1 μM) (d). Effects were measured on electrical field stimulated (10 Hz, 0.5 ms, 60 V for 2 s per minute) contractile responses of the rat prostate. Data points are the mean and vertical lines show s.e.m. of six experiments. P-values are for the concentration-treatment interaction of repeated-measures two-way ANOVA. Histogram columns represent the mean control force developed from contractile responses to electrical field stimulation in control and treated tissues. Bars represent s.e.m. *Significantly different from control, P<0.05 using Student's paired t-test.

Incubation with the CB1 selective antagonists, SR141716 (1 μM) and LY320135 (1 μM), had no significant effect on mean control responses to electrical field stimulation (P=0.460 and 0.802, respectively) (Figure 3b and c, respectively; n=6). Incubation with the CB2 selective antagonist, SR144528 (1 μM), increased mean control responses to electrical field stimulation (Figure 3d; P=0.015, n=6).

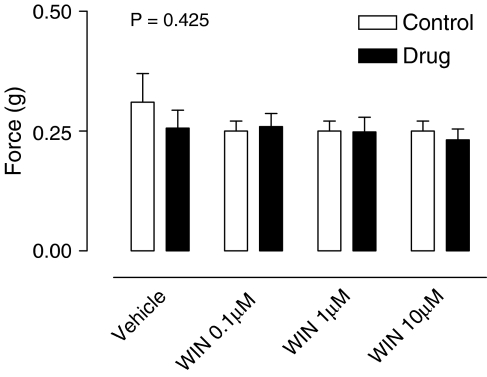

WIN 55,212-2 (0.1, 1 or 10 μM) had no significant effect on contractile responses mediated by exogenously added noradrenaline (1 μM) (Figure 4; P=0.425, n=6).

Figure 4.

Mean contractile responses to exogenous noradrenaline (1 μM) in the rat prostate in the absence and presence of WIN 55,212-2 (0.1, 1 and 10 μM). Data points are the mean and vertical lines show s.e.m. of six experiments. P-values are for the concentration-treatment interaction of repeated-measures two-way ANOVA.

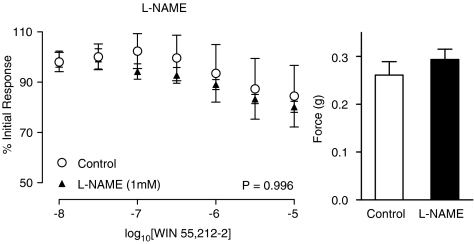

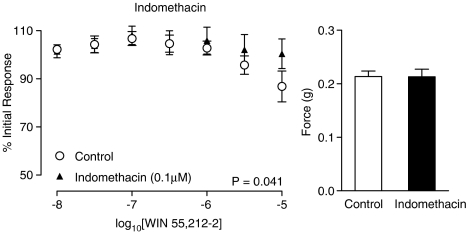

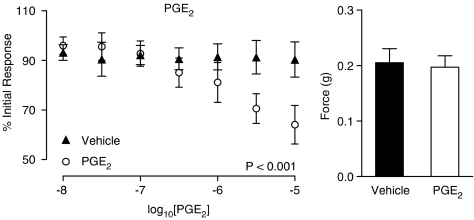

The nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-NAME had no effect on control electrical field stimulated contractions (Figure 5; P=0.409, n=6). L-NAME had no significant effect on the WIN 55,212-2-mediated inhibition at a concentration of 0.1 mM (figure not shown; P=0.710, n=6) or 1 mM (Figure 5; P=0.996, n=6). Indomethacin on the other hand blocked the inhibitory response seen with increasing concentrations of WIN 55,212-2 (Figure 6; P=0.041, n=6). Indomethacin had no effect on control contractions to electrical field stimulation (Figure 6; P=0.975, n=6). Prostaglandin E2 (10 nM–10 μM) caused a concentration-dependent inhibition of the contractions in response to electrical field stimulation (Figure 7; P<0.001, n=6), which was similar in quality and magnitude to that produced by WIN 55,212-2.

Figure 5.

Mean inhibitory log concentration–response curves to WIN 55,212-2 on electrical field stimulation (10 Hz, 0.5 ms, 60 V for 2 s per minute) induced contractile responses of the rat prostate in the absence and presence of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-NAME (1 mM). Data points are the mean and vertical lines show s.e.m. of six experiments. P-values are for the concentration-treatment interaction of repeated-measures two-way ANOVA. Histogram columns represent the mean control force developed from contractile responses to electrical field stimulation in control and treated tissues. Bars represent s.e.m.

Figure 6.

Mean inhibitory log concentration–response curves to WIN 55,212-2 on electrical field stimulation (10 Hz, 0.5 ms, 60 V for 2 s per minute)-induced contractile responses of the rat prostate in the absence and presence of the cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin (0.1 mM). Data points are the mean and vertical lines show s.e.m. of six experiments. P-values are for the concentration-treatment interaction of repeated-measures two-way ANOVA. Histogram columns represent the mean control force developed from contractile responses to electrical field stimulation in control and treated tissues. Bars represent s.e.m.

Figure 7.

Mean inhibitory log concentration–response curves to PGE2 on electrical field stimulation (10 Hz, 0.5 ms, 60 V for 2 s per minute)-induced contractile responses of the rat prostate. Data points are the mean and vertical lines show s.e.m. of six experiments. P-values are for the concentration-treatment interaction of repeated-measures two-way ANOVA. Histogram columns represent the mean control force developed from contractile responses to electrical field stimulation in control and treated tissues. Bars represent s.e.m.

Discussion

Using immunohistochemical techniques, we have demonstrated the presence of the CB1, but not the CB2 receptor in epithelial cells lining the secretory acini of the rat prostate. This is consistent with previous research using human prostate to display CB1 receptor expression in epithelial cells (Ruiz-Llorente et al., 2003). Staining in this study was primarily concentrated in the region of the epithelial nuclei and to a lesser extent the basal region of the epithelial cells. The morphological location of cannabinoid receptors in epithelial but not stromal cells would indicate a role in regulating secretion rather than contraction.

Previous studies in our laboratory have shown that the electrical field stimulation parameters used elicit contractions of the rat prostate which are predominantly neuronal and sympathetic in nature since they are attenuated by tetrodotoxin and guanethidine (Ventura et al., 2003). These contractions have also been shown to be mediated by cotransmission of noradrenaline and ATP (Ventura et al., 2003). As yet the effect of electrical stimulation on the release of epithelial mediators is unknown, but there is a tetrodotoxin-resistant component of electrical field stimulation-induced contractions using these parameters (Ventura et al., 2003). The synthetic cannabinoid, WIN 55,212-2, was chosen for use in functional experiments due to its high affinity for both cannabinoid receptor subtypes and high intrinsic activity as a full agonist (Pertwee, 1997; Howlett et al., 2002). Functional experiments revealed that WIN 55,212-2 caused a concentration-dependent inhibition of nerve-mediated responses in prostatic smooth muscle, which was reversed by selective antagonists for the CB1, but not the CB2 receptor. This indicates that the observed contractile inhibition is through CB1 receptor activation. The maximal inhibition seen with WIN 55,212-2 in the prostatic tissue was approximately 30% and was obtained at high concentrations, which may reflect the fact that it is harder to see an inhibitory effect on isolated tissues with high frequency stimulation rather than single pulses or due to the indirect route of cannabinoid influence on the prostatic smooth muscle.

The lack of any effect of the CB1 selective antagonists on field stimulation-induced responses suggests there is no basal endogenous cannabinoid release. This is in contrast to previous research done in the rat vas deferens where SR141716 increased the amplitude of electrically stimulated contractions (Christopoulos et al., 2001). The increase in the electrical field stimulated response following incubation with the selective CB2 receptor antagonist, SR144528, was unexpected considering that exogenous cannabinoids are unable to influence the contractile response via CB2 receptors.

The histological localization of the CB1 receptor in epithelial cells implies that inhibition is not through prejunctional nerve terminals, as seen in the rat vas deferens, mouse urinary bladder and the guinea-pig ileum (Pertwee and Fernando, 1996; Izzo et al., 1998; Christopoulos et al., 2001). However, functional experiments indicate that WIN 55,212-2 does not alter noradrenaline-induced responses, implying that cannabinoids are not acting postjunctionally on smooth muscle. The mechanism of action of WIN 55,212-2 appears to be through activation of CB1 receptors on epithelial cells to release an inhibitory signalling molecule that is able to inhibit electrical field stimulation-induced smooth muscle contractility by acting on prejunctional nerve endings.

Cannabinoid activation of endothelial CB1 receptors has been shown to cause release of nitric oxide in regions of vascular tissue in the kidney to cause vasodilatation (Deutsch et al., 1997). However, in contrast to this, WIN 55,212-2-mediated inhibition of prostatic contractions was not affected by the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-NAME. Endogenous cannabinoids have also been shown to activate TRPV1 receptors, found on sensory nerves, to mediate inhibition of electrically evoked contractions in the rat vas deferens (Ross et al., 2001). Calcitonin gene-related peptide has also been shown to be present in nerves (presumably sensory) innervating the rat prostate and to inhibit prostatic contractions (Ventura et al., 2000). Therefore, stimulation of TRPV1 receptors in rat prostate may conceivably also produce inhibition of rat prostatic contractions. However in this study, the chosen cannabinoid agonist WIN 55,212-2 lacks efficacy at the TRPV1 receptor avoiding conflicting results which may result using an endogenous cannabinoid such as anandamide (Zygmunt et al., 1999; Smart et al., 2000; Ross et al., 2001). Indomethacin on the other hand reversed the inhibitory effect of WIN 55,212-2, suggesting that CB1 receptor stimulation positively influences cyclooxygenase within the prostate. Human levels of cyclooxygenase mRNA are found to be highest in the prostate, and both the COX-1 and COX-2 isoforms are expressed (O'Neill and Ford-Hutchinson, 1993; Kirschenbaum et al., 2000). Furthermore, cannabinoids have previously been linked to increased prostaglandin E2 production in cell cultured fibroblasts derived from lung tissue (Burstein et al., 1982), so it is distinctly possible that CB1 receptor stimulation mediates inhibition in the rat prostate by increasing the synthesis of prostaglandin E2.

The possibility that the CB1 receptor is linked to the cyclooxygenase pathway needs to be explored further, including the effect of any molecular products. Preliminary evidence as seen in this study shows that prostaglandin E2 is able to inhibit electrically stimulated contractile responses in a concentration-dependent manner similar in magnitude to WIN 55,212-2. It has been shown that in the prostate molecular products of the COX pathway cause a contractile response, which contradicts what was observed in this study (Kitada and Kumazawa, 1987; Sudoh et al., 1997). However, in those studies prostaglandins were tested in the absence of any electrical field stimulation and this could account for the difference seen in the results.

These results suggest that cannabinoids potentially inhibit smooth muscle contractions by activating cannabinoid receptors of the CB1 receptor subtype, found within the epithelial layer. It has been previously shown that prostatic stromal and epithelial layers are capable of communicating through paracrine mediators, as regards cellular proliferation (Farnsworth, 1999), and it has been suggested that in rabbit mesenteric artery, cannabinoids can relax smooth muscle cells by promoting diffusion of an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor via gap junctions (Chaytor et al., 1999). However, this is the first study to suggest that mediators from epithelial cells may influence contractility of the adjacent stromal smooth muscle cells in the prostate. A factor which needs to be taken in to consideration while interpreting these results is that it is possible for electrical stimulation to cause epithelial secretion, as seen in the dog prostate gland (Smith et al., 1983). This secretion in response to electrical stimulation also peaks in the first minute of stimulation and then subsides (Smith et al., 1983), therefore certain mediators necessary to influence contractile responses may get depleted from the epithelial cells. This may account for the low effect seen with WIN 55,212-2.

In conclusion, WIN 55,212-2 causes inhibition of electrical field stimulation-induced contractions of the smooth muscle in the rat prostate, via epithelial CB1 receptors. The cyclooxygenase pathway appears to be involved, suggesting that stimulation of CB1 receptors present on prostate epithelial cells may cause release of a prostaglandin to produce smooth muscle relaxation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants to SV from the NHMRC (Australia), Ramaciotti Foundation and Mary and Arthur Osborne Estate. Authors are also grateful to Sanofi-Recherche for their generous gifts of SR141716 and SR144528, and to Eli Lilly for their generous gift of LY320135.

Abbreviations

- ATP

adenosine 5′-trisphosphate

- CB

cannabinoid

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- L-NAME

Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- TRPV1

transient receptor potential type V1

Conflict of interest

SR141716 and SR144528 were generously donated by Sanofi-Recherche, and LY320135 was donated by Eli Lilly. This manuscript has been approved for publication by Eli Lilly.

References

- Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA.Guide to receptors and channels Br J Pharmacol 2006147Suppl 3S1–S168.2nd edn, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein S, Hunter SA, Sedor C, Shulman S. Prostaglandins and cannabis – IX. Stimulation of prostaglandin E2 synthesis in human lung fibroblasts by delta 1-tetrahydrocannabinol. Biochem Pharmacol. 1982;31:2361–2365. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(82)90530-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaytor AT, Martin PE, Evans WH, Randall MD, Griffith TM. The endothelial component of cannabinoid-induced relaxation in rabbit mesenteric artery depends on gap junctional communication. J Physiol. 1999;520 Part 2:539–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos A, Coles P, Lay L, Lew MJ, Angus JA. Pharmacological analysis of cannabinoid receptor activity in the rat vas deferens. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:1281–1291. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch DG, Goligorsky MS, Schmid PC, Krebsbach RJ, Schmid HH, Das SK, et al. Production and physiological actions of anandamide in the vasculature of the rat kidney. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1538–1546. doi: 10.1172/JCI119677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth WE. Prostate stroma: physiology. Prostate. 1999;38:60–72. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19990101)38:1<60::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flickinger CJ. The fine structure of the interstitial tissue of the rat prostate. Am J Anat. 1972;134:107–125. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001340109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward SW. Approaches to modeling stromal-epithelial interactions. J Urol. 2002;168:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64620-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho WS, Hiley CR. Endothelium-independent relaxation to cannabinoids in rat-isolated mesenteric artery and role of Ca2+ influx. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:585–597. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett AC, Barth F, Bonner TI, Cabral GA, Casellas P, Devane WA, et al. International Union of pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:161–202. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishac EJ, Jiang L, Lake KD, Varga K, Abood ME, Kunos G. Inhibition of exocytotic noradrenaline release by presynaptic cannabinoid CB1 receptors on peripheral sympathetic nerves. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:2023–2028. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo AA, Mascolo N, Borrelli F, Capasso F. Excitatory transmission to the circular muscle of the guinea-pig ileum: evidence for the involvement of cannabinoid CB1 receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:1363–1368. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesik CJ, Holland JM, Lee C. An anatomic and histologic study of the rat prostate. Prostate. 1982;3:81–97. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990030111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschenbaum A, Klausner AP, Lee R, Unger P, Yao S, Liu XH, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 in the human prostate. Urology. 2000;56:671–676. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada S, Kumazawa J. Pharmacological characteristics of smooth muscle in benign prostatic hyperplasia and normal prostatic tissue. J Urol. 1987;138:158–160. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)43034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Sensibar JA, Dudek SM, Hiipakka RA, Liao ST. Prostatic ductal system in rats: regional variation in morphological and functional activities. Biol Reprod. 1990;43:1079–1086. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.6.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda LA, Lolait SJL, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterisation of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61–65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy LL, Munoz RM, Adrian BA, Villanua MA. Function of cannabinoid receptors in the neuroendocrine regulation of hormone secretion. Neurobiol Disease. 1998;5:432–446. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill GP, Ford-Hutchinson AW. Expression of mRNA for cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 in human tissues. FEBS Lett. 1993;330:156–160. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80263-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Pharmacology of cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;74:129–180. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)82001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG, Fernando SR. Evidence for the presence of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in mouse urinary bladder. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:2053–2058. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit V, Ahluwalia BS, Vigersky RA. Marihuana inhibits dihydrotestosterone binding to the androgen receptor. Endocrinology. 1980;107:848–850. doi: 10.1210/endo-107-3-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RA, Gibson TM, Brockie HC, Leslie M, Pashmi G, Craib SJ, et al. Structure-activity relationship for the endogenous cannabinoid, anandamide, and certain of its analogues at vanilloid receptors in transfected cells and vas deferens. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:631–640. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Llorente L, Ortega-Gutierrez S, Viso A, Sanchez MG, Sanchez AM, Fernandez C, et al. Characterization of an anandamide degradation system in prostate epithelial PC-3 cells: synthesis of new transporter inhibitors as tools for this study. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:457–467. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Llorente L, Sanchez MR, Carmena MJ, Prieto JC, Sanchez-Chapado M, Izquierdo A, et al. Expression of functionally active cannabinoid receptor CB1 in the human prostate gland. Prostate. 2003;54:95–102. doi: 10.1002/pros.10165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart D, Gunthorpe MJ, Jerman JC, Nasir S, Gray J, Muir AI, et al. The endogenous lipid anandamide is a full agonist at the human vanilloid receptor (hVR1) Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:227–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ER, Miller TB, Pebler RF. Transepithelial voltage changes during prostatic secretion in the dog. Am J Physiol. 1983;245:F470–F477. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1983.245.4.F470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudoh K, Inagaki O, Honda K. Responsiveness of smooth muscle in the lower urinary tract of rabbits to various agonists. Gen Pharmacol. 1997;28:629–631. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura S, Dewalagama RK, Lau LCL. Adenosine 5′-trisphosphate (ATP) is an excitatory cotransmitter with noradrenaline to the smooth muscle of the rat prostate gland. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:1277–1284. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura S, Lau WA, Buljubasich S, Pennefather JN. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) inhibits contractions of the prostatic stroma of the rat but not the guinea-pig. Regul Pept. 2000;91:63–73. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt PM, Petersson J, Andersson DA, Chuang H, Sorgard M, Di Marzo V, et al. Vanilloid receptors on sensory nerves mediate the vasodilator action of anandamide. Nature. 1999;400:452–457. doi: 10.1038/22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]