Abstract

The vascular endothelium of the coronary arteries has been identified as the important organ that locally regulates coronary perfusion and cardiac function by paracrine secretion of nitric oxide (NO) and vasoactive peptides. NO is constitutively produced in endothelial cells by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). NO derived from this enzyme exerts important biological functions including vasodilatation, scavenging of superoxide and inhibition of platelet aggregation. Routine cardiac surgery or cardiologic interventions lead to a serious temporary or persistent disturbance in NO homeostasis. The clinical consequences are “endothelial dysfunction”, leading to “myocardial dysfunction”: no- or low-reflow phenomenon and temporary reduction of myocardial pump function. Uncoupling of eNOS (one electron transfer to molecular oxygen, the second substrate of eNOS) during ischemia-reperfusion due to diminished availability of L-arginine and/or tetrahydrobiopterin is even discussed as one major source of superoxide formation. Therefore maintenance of normal NO homeostasis seems to be an important factor protecting from ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. Both, the clinical situations of cardioplegic arrest as well as hypothermic cardioplegic storage are followed by reperfusion. However, the presently used cardioplegic solutions to arrest and/or store the heart, thereby reducing myocardial oxygen consumption and metabolism, are designed to preserve myocytes mainly and not endothelial cells. This review will focus on possible drug additives to cardioplegia, which may help to maintain normal NO homeostasis after I/R.

Keywords: cardioplegia, nitric oxide, ischemia–reperfusion, heart

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) has been identified as a key regulator of vascular function, representing one of the most powerful vasodilators, antagonizing vasoconstrictors such as endothelin. Consequently, an imbalance in NO production, availability or increased NO degradation on the one hand and increased endothelin production or reduced degradation on the other hand leads to vasoconstriction. In contrary, NO overproduction seen in acute organ rejection or during septic shock leads to vasoplegia. Therefore it is fair to say that NO homeostasis is the precondition for physiologic blood pressures and flow conditions. The action of NO in vascular and cardiovascular regulation is not limited to its vasodilatation properties. NO inhibits platelet aggregation, reduces oxygen consumption, has lusotropic potential, influences directly or indirectly myocardial contractility, scavenges superoxide (O2−) (antioxidant properties), prevents leukocyte adhesion and is an antiproliferative and anti-inflammatory mediator.

It is of common knowledge that atherosclerosis affects the major site of NO production, the endothelium. The clinical consequences of atherosclerosis are coronary artery and/or peripheral artery disease, hypertension, stroke, and so on. On the basis of severe atherosclerosis, routine cardiac surgery or cardiologic interventions lead to a serious temporary or persistent disturbance in NO homeostasis. The clinical consequences of persistent impaired NO activity and increased radical oxygen species activity lead to ‘endothelial dysfunction' and ultimately to ‘myocardial dysfunction': no- or low-reflow phenomenon and temporary reduction of myocardial pump function.

However, solutions to arrest the heart during cardiac surgery, the so-called cardioplegic solutions, have been primarily designed to protect the myocytes from ischemia and the following reperfusion (Bretschneider et al., 1975; Braimbridge et al., 1977; Buckberg 1979; Southard, 1995). Cardiovascular research has recognized rather late that the endothelium of the heart is an important organ that locally regulates coronary perfusion and cardiac function by paracrine secretion of NO and vasoactive peptides (Linz et al., 1992). Therefore cardioplegic solutions in general and storage solutions in cardiac transplantation in particular are now critically discussed with respect to preservation of both myocytes and endothelial integrity and function.

This review will focus on NO homeostasis as a target for drug additives to cardioplegia. The maintenance of NO homeostasis is a complex field and in the case of cardioplegia directly related to prevention of ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) damage. Strategies for additives to cardioplegic solutions include calcium antagonists, scavengers of O2− and indirect and direct supplementation of NO. Therefore we briefly address the following topics:

NO homeostasis in the cardiovascular system

Disturbed NO homeostasis during I/R

Clinical state of the art to preserve the heart during cardiac surgery and transplantation

The endothelium as a target for cardioplegic solutions

Discussion and outlook

NO homeostasis in the cardiovascular system

NO pathway

NO is constitutively produced under physiologic conditions by the two isoenzymes eNOS (endothelial nitric oxide synthase, NOS-3) and nNOS (neuronal nitric oxide synthase, NOS-1) that are both calcium and calmodulin dependent, and a third enzyme, iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase, NOS-2) which is independent of the calcium–calmodulin pathway and not expressed under physiologic circumstances in the endothelium (Balligand and Cannon, 1997). Within the cardiovascular system, eNOS is the most important isoform. eNOS is a Ca2+-, NADPH-, flavin- and biopterin-dependent enzyme, which utilizes the guanido nitrogen atom of L-arginine and incorporates molecular oxygen to generate NO and L-citrulline (Wu, 2002). Thus, NO is concerned with the regulation of vascular tone by inducing relaxation of vascular smooth muscle cells through stimulation of the enzyme-soluble guanylyl cyclase. Activation of soluble guanylate cyclase leads to conversion of magnesium guanosine 3′,5′-triphosphate to the second messenger guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate guanosine, which stimulates two cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-dependent protein kinases (PKG I and PKG II) (Kojda and Kottenberg, 1999). PKG I is the major kinase-mediating vasodilatation and inhibition of platelet aggregation. PKG I acts via a phosphorylization of phospholamban and a phosphorylization of the 1,4,5-inositoltriphosphate receptor-associated cGMP kinase substrate. The activity of cGMP is terminated by a rapid conversion to GMP, catalyzed by various phosphodiesterases (Moncada et al., 1991; Gewaltig and Kojda, 2002).

NO-mediated effects

Produced by endothelial cells, NO is responsible for the following actions:

vasodilatation (Ignarro et al., 1987)

inhibition of platelet aggregation (Azuma et al., 1986; Radomski et al., 1987; Kalinowski et al., 2002)

reduction of oxygen consumption (Loke et al., 1999; Recchia et al., 1999)

lusitropy (an increase in cardiac compliance) (Paulus and Shah, 1999) and therefore

a direct- or indirect-mediated increase in myocardial contractility (Brady et al., 1993; Kanai et al., 1997)

scavenging of O2− (antioxidant properties) (Beckman et al., 1990)

prevention of leukocyte (neutrophil) adhesion (Ma et al., 1993)

reduction of proliferation and inflammation (Garg and Hassid, 1989; Wright et al., 1992)

After cardioplegic arrest and storage initial reperfusion is a critical step. Better organ preservation with improved cardioplegic solutions focusing on both, myocytes and endothelial cells, are of major interest. Also the first step of many, leading to successful heart transplantation is adequate organ preservation ensuring maintenance of organ viability and function. Thereby, the major challenge is to minimize pathologic damage and impairment of function because during procurement, storage and implantation, the heart is always exposed to I/R.

Disturbed NO homeostasis during I/R

Re-establishing blood flow to ischemic tissues or organs (reperfusion) is an essential step in many surgical procedures (Korthuis et al., 1985), including reperfusion after cardioplegic arrest or transplantation of the heart after organ preservation in cardioplegic solutions. However, reperfusion, especially after prolonged ischemia, leads to changes in vasomotility and an increase in microvascular permeability causing tissue reperfusion edema (Sternbergh et al., 1993). These are constant features of I/R injury. The consequences of such an injury are frequently massive edema formation and tissue destruction (Baue, 1992; Grace, 1994). Constitutive eNOS plays a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of I/R injury. The onset of ischemia leads to elevated intracellular calcium ion concentrations mediated by increased levels of catecholamines. These increased calcium ion concentrations activate eNOS (enhanced generation of NO). Data by Huk et al. (1997) and Hallström et al. (2002) also show that I/R injury is initiated by a massive burst of NO production (measured in vivo with a porphyrinic-based microsensor – Malinski and Taha, 1992) after onset of ischemia, which depletes local L-arginine and/or (6R)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) concentrations, followed by high production of O2− after reperfusion and consequently high production of peroxynitrite. It has become clear from studies with purified eNOS that under substrate or cofactor depletion, the enzyme may become ‘uncoupled'. In such an uncoupled state, electrons are rather diverted to molecular oxygen rather than to L-arginine, resulting in production of O2− (Xia and Zweier, 1997; Vasquez-Vivar et al., 1998) and consequently high production of peroxynitrite. Although the mechanisms underlying endothelial dysfunction are likely to be multifactorial, it is important to note that increased production of oxygen-derived free radicals by an uncoupled eNOS markedly contributes to this phenomenon (Münzel et al., 2005).

The formation of excessive local peroxynitrite concentrations and consequent cleavage products during the initial phase of reperfusion is deleterious. Three of these cleavage products (hydroxyl free radical, nitrogen dioxide free radical and nitronium cation) are among the most reactive and damaging species and may be major contributors to the severe I/R damage (Huk et al., 1997). The pathophysiologic settings mentioned above are associated with endothelial dysfunction. In cardiac transplantation I/R, hypothermia and atherosclerosis are of particular interest. The first two pathologic conditions contribute to endothelial dysfunction during and shortly after transplantation. Atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries of the transplanted organ, to some extent being a result of the endothelial dysfunction set by hypothermia and I/R, is one of the leading causes for deaths years after transplantation and is directly related to the time of ischemia of the allograft (Valantine, 2003; Weis and Cooke, 2003).

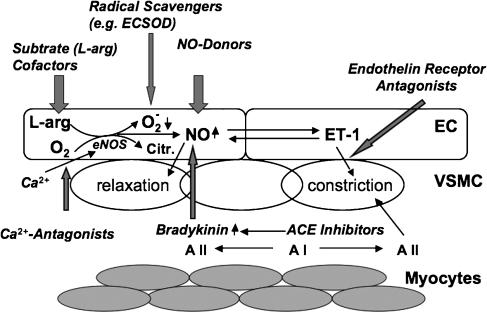

The immediate consequences of I/R and hypothermia are endothelial dysfunction: vasoconstriction due to decreased NO production or bioavailability and dominance of endothelins, a group of vasoactive peptides, produced by the endothelium (Gourine et al., 2001; Laude et al., 2001). This leads to no reflow and finally to organ failure. In the heart, this temporary failure is called ‘myocardial stunning'. The term myocardial stunning, as it is used by many authors, is characterized as a mechanical dysfunction that persists after reperfusion despite the absence of irreversible damage and despite restoration of normal or near-normal coronary blood flow. This implies that this is a postischemic dysfunction that is fully reversible, no matter how severe or prolonged, and that the dysfunction is not caused by a primary deficit of myocardial perfusion (Bolli, 1990). Figure 1 summarizes the effect of I/R on NO homeostasis and depicts possible targets of therapeutic intervention.

Figure 1.

Nitric oxide (NO) homeostasis as a target for drug additives to cardioplegia – possible routes: following reperfusion after cardioplegia, the levels of NO are decreased mainly due to ‘uncoupling' of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), which leads to enhanced level of superoxide (O2−). This results in increased vascular tone due to reduced bioavailability of NO and therefore reduced relaxation as well as enhanced production of the vasoconstrictors endothelin-1 (ET-1) and angiotensin II (A II). This reperfusion injury can be attenuated by enhancing the levels of bioavailable NO with substrates/cofactors of eNOS, NO-donors (feedback inhibition and prevention of ‘uncoupling'), bradykinin, blocking ET-I receptors, blocking the receptors (AT-I) or production (ACE- inhibitors) of angiotensin II and free radical scavengers of superoxide such as extracellular superoxide dismutase (ECSOD). Calcium antagonists on the other hand can counteract the initial Ca2+ increase at the onset of ischemia and prevent eNOS stimulation. The enhanced (normalized) levels of bioavailable NO, for example, attenuate/prevent inflammation by inhibiting the activation of the proinflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and cell adhesion molecules. As consequence this results in a decreased expression of proinflammatory cytokines and reduced leukocyte (neutrophil) adhesion. The above figure mainly illustrates the possible routes of intervention.

Clinical state of the art to preserve the heart during cardiac surgery and transplantation

Cardioplegic arrest

Till date, the vast majority of heart operations are performed on the arrested heart. Exceptions are so-called off-pump coronary artery revascularizations. The numbers differ largely between countries and centers, in Europe approximately 15% of all coronary bypass operations are performed without cardiac arrest and consequently without the use of the heart–lung machine (HLM). The possible advantage of off-pump surgery is its minimal invasiveness, defined in this case not by a limited skin incision but by a reduction in the side effects of the HLM on inflammation. The results so far show that patients with high co-morbidities, such as renal failure, reduced cardiac function or a history of neurological complications benefit most. However, for the majority of patients undergoing coronary revascularization, no difference has been identified between on- and off-pump surgery (Sellke et al., 2005). In all other surgical procedures, especially those, where the heart has to be opened such as in pediatric and valve surgery as well as in cardiac transplantation, cardioplegic arrest is mandatory.

The concept of cardiac arrest has been developed by the demands of cardiac surgeons to replace a calcified, stenotic valve or to perform a perfect communication between two vessels (anastomosis) with small diameters. However, uncoupling the heart from its natural source of oxygen and fuel (carbohydrates and fatty acids) leads to I/R damage and ultimately to myocardial infarction. Therefore, strategies were developed to enable this necessary uncoupling already from the very beginning of cardiac surgery (Melrose et al., 1955; Shumway et al., 1959). Common goal is the reduction of myocardial oxygen consumption either by hypothermia or by uncoupling of cardiac contraction. The former is based on experimental data showing that reduction of myocardial temperature from 37 to 22°C reduces oxygen consumption by 90% (Buckberg et al., 1977). The latter is based on the fact that 60–70% of cardiac energy goes into contraction. Hyperpolarization by K+, Mg+ or Na+ containing cardioplegic solutions induces cardiac arrest even under normothermic conditions (Bretschneider et al., 1975; Braimbridge et al., 1977). Till date, a combination of these two techniques is the gold standard of myocardial protection for heart procurement. In general, cardiac surgery temperature can vary from cold to tepid or normothermia, according to the patients special needs and the surgeons preferences (Guru et al., 2006).

Depending on the concentration of Na+, two types of cardioplegic solutions can be distinguished: intra- and extracellular solutions (Podesser et al., 1996). In Europe, the clinically most relevant intracellular solution is Bretschneider's HTK solution with a Na+ concentration of 15 mmol/l compared to the extracellular solutions such as St Thomas' cardioplegia (Na+ 117 mmol/l) or blood cardioplegia according to Buckberg (Na+ 120 mmol/l). Especially, HTK is also widely accepted as storage solution for cardiac transplantation together with Celsior, a solution designed to combine the general principles of hypothermic organ preservation specific to the heart with the possibilities to use it also during initial donor arrest, poststorage graft reimplantation and early reperfusion (Perrault et al., 2001).

Whenever the aortic root is not only clamped but also dissected and the heart is arrested and excised for organ procurement, it has to be stored. Again, these storage solutions have been designed as cardioplegic solutions for myocyte preservation only. Current clinical routine allows 4–5 h maximum for organ procurement, transport and beginning of reperfusion (Jahania et al., 1999). Experiments conducted with isolated porcine coronary endothelial cells to investigate the effect of cold ischemic storage of these cells in University of Wisconsin solution, another storage solution, mainly used for visceral organs in the US, have shown that a significant decrease in eNOS activity was seen after storage for more than 6 h. There was no significant decrease in cells subjected to cold ischemic storage for 1 h only (Redondo et al., 2000).

However, with an increase in the average life span, cardiac surgeons face an older population of patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery, valve replacement and reconstruction as well as transplantation. This cohort of patients is more likely to have impaired endothelial function. Consequently new strategies have to be developed to maintain operative mortality and morbidity at acceptable levels.

The endothelium as a target for cardioplegic solutions

Additives to cardioplegic solutions influencing NO homeostasis

Radical scavengers

Scavenging of O2− may increase NO bioavailability (Table 1). Indeed, in the past three decades, much work has been performed to use superoxide dismutase (SOD) as a therapeutic agent. Most efforts focused on cytosolic SOD, although it is not normally found in extracellular sites. Despite some success in experimental studies, there has been little success in clinical applications. The variable effects of cytosolic SOD may be related to the limited cell penetration of the exogenous-applied cytosolic enzyme.

Table 1.

Additives to cardioplegic solutions influencing NO homeostasis (most relevant experimental and clinical studies)

| Additives | Results | References |

|---|---|---|

| Radical scavengers | ECSOD type C is cardioprotective in isolated cold-arrested rat hearts; human chimeric SOD improves myocardial preservation in the rabbit heart | Sjöquist et al. (1991), Hatori et al. (1992), Nelson et al. (2002) |

| Calcium antagonists | Diltiazem protects lipid fraction within the cell membrane | |

| Against the toxic effects of free oxygen radicals | Koller and Bergmann (1989), Kröner et al. (2002) | |

| Diltiazem reduces infarct size and protects against reperfusion injury | Tadokoro et al. (1996), Klein et al. (1984) | |

| ACE inhibitors | Quinaprilat improves postischemic systolic and diastolic function, coronary perfusion and energy phosphates in the healthy rabbit and the failing rat heart undergoing I/R | Korn et al. (2002), Podesser et al. (2002) |

| Captopril and TCV-116 reduce chronic allograft rejection | Furukawa et al. (1996) | |

| Bradykinin | Bradykinin preconditioning improves postischemic left ventricular and microvascular function | Feng et al. (2000, 2006) |

| Endothelin receptor antagonists | Bosentan preserves endothelial and cardiac contractile function during I/R in isolated rat and mouse hearts via a NO-mediated mechanism | Gonon et al. (2004) |

| TBC-3214Na improves postischemic systolic and diastolic function, in the failing rat heart undergoing I/R | Trescher et al. (2006) | |

| Substrates and cofactors of eNOS | L-arginine cardioplegia supplementation reduces troponin T and CK-MB levels in CABG | Carrier et al. (2002), Kiziltepe et al. (2004) |

| L-arginine reduces cytokine release and wedge pressure in CABG | Colagrande et al. (2006) | |

| BH4 is cardioprotective in cold rat heart preservation | Yamashiro et al. (2003) | |

| NO-releasing compounds | S-nitrosoglutathione monoethyl ester shows protective effects during cardioplegic arrest in isolated rat hearts | Konorev et al. (1996) |

| S-NO-HSA improves functional and metabolic outcome after cold organ storage in the isolated rabbit heart (6 h) | Semsroth et al. (2005) | |

| and in orthotopically transplanted pig hearts (4h) | Gottardi et al. (2004) |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; BH4, (6R)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CK-MB, creatinine kinase-myocardial band; ECSOD, extracellular superoxide dismutase; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; NO, nitric oxide; TBC-3214Na, selective endothelin A-receptor blocker; TCV-116, selective angiotensin II-receptor blocker; S-NO-HSA, S-nitroso human serum albumin; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

New approaches focus on therapeutic equivalents of extracellular superoxide dismutase (ECSOD), which is electrostatically bound to heparan sulfate proteoglycans in the glycocalyx of various cell types (for example, endothelial cells). The ECSOD is the major SOD in extracellular fluids. ECSOD has a highly hydrophylic positively charged, carboxyl terminal that imparts the high heparin affinity, which allows the enzyme to be bound to heparin sulfate proteoglycans on endothelial surfaces (Sandstrom et al., 1992). Recombinant human ECSOD type C has been shown to have cardioprotective effects in isolated rat heart subjected to I/R (Sjöquist et al., 1991) as well as in isolated cold-arrested rat hearts (Hatori et al., 1992). More recently a human chimeric SOD, a product of a fusion gene encoding a mutant manganese SOD and the carboxy terminal 26-aminoacid tail from ECSOD, has shown to improve myocardial preservation of isolated rabbit hearts subjected to warm and cold ischemia (Nelson et al., 2002).

Calcium antagonists

A number of studies have reported that administration of diltiazem before or during I/R reduces infarct size and protects against reperfusion injury (Klein et al., 1984; Seitelberger et al., 1994; Tadokoro et al., 1996). The beneficial effects of diltiazem on ischemic myocardium are generally thought to be due to coronary artery vasodilatation and a decrease of heart rate as well as cardiac contractility (Ferrari and Visioli, 1991). The net result of these effects is a reduction in the imbalance between oxygen supply and demand in acutely ischemic myocardium, through a simultaneous increase in collateral blood flow (mediated by coronary vasodilatation) and a reduction in oxygen consumption (secondary to a decrease in heart rate, contractility and afterload).

It has become apparent that free oxygen radical generation and calcium overload contribute to the development of reperfusion injury (Hess and Manson, 1984; Ferrari, 1996). We and others have shown data that suggest that calcium antagonists protect the lipid fraction within the cell membrane against the toxic effects of free oxygen radicals (Koller and Bergmann, 1989; Kröner et al., 2002). Lipid peroxidation is considered a major mechanism of oxygen radical toxicity, thereby altering membrane permeability (Hess and Manson, 1984; Ambrosio et al., 1991). Calcium antagonists administered before ischemia may help maintaining NO homeostasis by preventing activation of eNOS and thereby preventing ‘uncoupling'.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and bradykinin

There have been numerous experimental (Kitakaze et al., 1995; Zahler et al., 1999; Korn et al., 2002) and clinical reports (GISSI-3 APPI study Group, 1996; Lazar et al, 1998) on the beneficial action of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors in the setting of I/R. The concept behind the use of ACE inhibitors is well understood: ACE is also known as kininase II. This dual enzymatic position explains its dual action: on the one hand, the conversion of angiotensin I (AT I) to angiotensin II is blocked, leading directly to vasorelaxation; on the other hand, the breakdown of bradykinin is blocked, leading to an increase in NO with consequent vasodilatation (Hartmann, 1995). The cardioprotective effect of ACE inhibitors could be abolished by the presence of icatibant (HOE 140), a specific bradykinin-B2 receptor antagonist (Linz et al., 1992).

Similarly, both captopril and lisinopril were able to enhance subthreshold preconditioning by augmenting bradykinin levels, an effect also eliminated by icatibant (Morris and Yellon, 1997). However, the ability of ACE inhibitors to confer protection in the absence of a preconditioning stimulus is more controversial (see Review from Baxter and Ebrahim, 2002). Experimental studies have used bradykinin preconditioning before ischemic arrest with cold crystalloid cardioplegia (Feng et al., 2005, 2006). In the cardiovascular system, the action of bradykinin is vasodilatation, mediated in several vascular beds by the release of NO and prostacyclin (Hatta et al., 1997; Wirth et al., 1997). Pretreating the heart with bradykinin before crystalloid cardioplegic ischemia significantly improved postischemic left ventricular and microvascular function, suggesting that pharmacological bradykinin may be an important addition to our current methods of myocardial and microvascular protection with hyperkalemic cardioplegia (Feng et al., 2000).

In two recent studies we have shown that preischemic ACE inhibition can significantly improve myocardial function in the healthy and in the failing heart, undergoing I/R compared to cardioplegia alone. The treated hearts showed an improvement in postischemic systolic and diastolic function, coronary perfusion as well as higher levels of high-energy phosphates (Korn et al., 2002; Podesser et al., 2002). The direct use of ACE inhibitors in the setting of heart transplantation is rare. Sasayama and co-workers report on the effect of captopril and a selective angiotensin II (AT II)-receptor blocker in a murine model of graft sclerosis. Both, the ACE inhibitor and the AT II receptor blocker were able to reduce chronic allograft rejection compared to controls (Furukawa et al., 1996).

Endothelin receptor antagonists

Another endothelium-derived substance is the potent vasoconstrictor endothelin 1 (ET-1) (Yanagisawa et al., 1988). ET-1 mediates vasoconstriction by binding to the endothelin type A and B receptors located on the smooth muscle cells. ET-1 may also mediate NO-dependent vasodilatation by activation of the endothelin type B receptor located on the vascular endothelium (de Nucci et al., 1988; Arai et al., 1990; Sakurai et al., 1990). NO not only counteracts the vasoconstrictor effect (Kourembanas et al., 1991) but also inhibits the release of ET-1 from endothelial cells (Boulanger and Lüscher, 1990). The production and release of ET-1 is increased during ischemia and contributes to I/R-injury. Selective ETA and mixed ETA/ETB receptor agonists have been shown to be cardioprotective in I/R. For instance, the dual ETA/ETB receptor agonist bosentan has been shown to preserve endothelial and cardiac contractile function during I/R in isolated rat and mouse hearts via a mechanism depending on endothelial NO production (Gonon et al., 2004). Similarly, we have studied the selective ETA-receptor blocker TBC1421 as an adjunct to blood cardioplegia in healthy and failing rat hearts in the setting of acute and chronic ischemia. Interestingly, cardiac function was preserved in both, the acute and the chronic treatment group, whereas preservation of coronary relaxation was seen only in the acute group (Trescher et al., 2006). These additional cardioprotective effects of ET-receptor blockers are especially important, as chronic treatment with ET-receptor blockers is currently only used in the clinical situation of severe pulmonary hypertension.

Substrates and cofactors of eNOS

L-Arginine

The most widely investigated additive to cardioplegia concerning NO homeostasis is L-arginine. The NOS substrate L-arginine has been reported to be effective as a supplement to cardioplegia in a dose range between 2 and 5 mmol/l in numerous experimental studies. The critical timing of L-arginine in cardioplegic arrest and reperfusion seems to be important. It has been shown in isolated working rat hearts that L-arginine given during initial reperfusion is deleterious to recovery of myocardial function. However, given before cardioplegic arrest, it exerts its beneficial effects (Engelman et al., 1996). Furthermore, different effects of L-arginine after cardioplegic arrest under moderate and deep hypothermia in isolated working rat hearts have been reported (Amrani et al., 1997). In this study, L-arginine as an additive to St Thomas' No 1 cardioplegic solution was effective only after moderate hypothermic ischemia (1 h; 20°C) and not after deep hypothermic ischemia (4 h; 4°C). Temperature therefore seems to be another important factor. The different approaches include supplementation of L-arginine during warm blood cardioplegia (Hayashida et al., 2000), supplementation of L-arginine directly to different cardioplegic solutions before short- (Amrani et al., 1997) and long-term ischemia in isolated working rat hearts (Desrois et al., 2000), or in a heterotopic rat heart transplantation model (Caus et al., 2003). In a recent paper on cardiac allograft preservation in an orthotropic cardiac transplant pig model using intermittent perfusion of donor-shed blood supplemented with L-arginine the question of the dose is addressed. The low dose group (L-arginine: 2.5 mmol/l) in this study showed a greater ability to wean-off cardiopulmonary bypass had an improved recovery of left ventricular function and a decreased release of inflammatory cytokines compared to control. In contrast, the high dose group (L-arginine: 5.0 mmol/l) resulted in severe endothelial injury in terms of uniform ischemic contracture and no recovery of ventricular function after 5 h of global ischemia (Ramzy et al., 2005).

Recently, the first clinical studies about the use of L-arginine in addition to cardioplegia demonstrated efficacy in reducing postoperative troponin T and creatinine kinase-myocardial band levels in coronary bypass graft operations (Carrier et al., 2002; Kiziltepe et al., 2004). A more recent study also showed reduced cytokine release (significant for interleukin 6) and myocardial damage (troponin T) in coronary artery bypass patients due to L-arginine cardioplegia supplementation. Wedge pressure as a clinical surrogate for ventricular volume load and intensive care unit stay was also significantly reduced in the treatment group (Colagrande et al., 2006). All these studies have in common that high doses of L-arginine added to the first 500 ml solution, that is, 7.5 g L-arginine in 500 ml of cardioplegia (Carrier et al., 2002; Colagrande et al., 2006) were used with best results when warm (33°C) cardioplegia was infused. Lower doses are safe but inefficient (Carrier et al., 1998). According to the results of experimental work, all the above clinical approaches were preformed by addition of L-arginine to cardioplegia before reperfusion.

Cofactors of eNOS

BH4 is an absolute cofactor required for NO synthase and is thus a critical determinant of NO production. Activation of purified eNOS in the presence of suboptimal levels of BH4 results in uncoupling. The concomitant addition of L-arginine and BH4 abolishes O2− generation by eNOS (Vasquez-Vivar et al., 1998).

Furthermore, in human aortic endothelial cells exposed to prolonged stretching, inhibition of BH4 synthesis has been shown to stimulate O2− production (Hishikawa and Lüscher, 1997). Effects of BH4 (20 μmol/l) supplementation have been studied in an in vitro human ventricular heart cell model of simulated I/R cellular injury, as assessed by means of trypan blue uptake, was significantly prevented (Verma et al., 2002). Very recently, cardioprotective effects of BH4 in cold heart preservation (4°C) have been shown by Yamashiro et al. (2003). BH4 improved the contractile and metabolic abnormalities in the reperfused cold preserved rat hearts that were subjected to normothermic ischemia. Additionally BH4 significantly alleviated ischemic contracture during ischemia and restored the perfusate levels of nitrite plus nitrate.

The cardioprotective effect of BH4 implies that BH4 could be a novel therapeutic option. Although not discussed by the authors it is known that BH4 is a very unstable compound, which is rapidly oxidized to dihydrobiopterin. Therefore, the compound in solution is presumably dihydrobiopterin, which is intracellulary converted to BH4 by dihydrobiopterin reductase with NADPH. In part, this possibility is discussed by Hasegawa et al. (2005).

NO-releasing compounds

In models of myocardial I/R injury, damage can also be reduced by addition of exogenous NO either as authentic NO gas (Johnson et al., 1991) or NO-donating compounds (Siegfried et al., 1992; Bilinska et al., 1996). Similarly, in the setting of organ transplantation, improved organ function has been observed when exogenous NO-donating agents have been included in the hypothermic storage solution in a heart model (Pinsky et al., 1994). Exogenous NO exhibits a negative feedback on the production of NO by eNOS (product inhibition of the enzyme; Griscavage et al., 1995) and thereby can prevent uncoupling of the enzyme in I/R. NO donors used in storage solutions to date have been glyceryl trinitrate (Bhabra et al., 1997), sodium nitroprusside (SNP) (Yamashita et al., 1996) and diazeniumdiolates (Du et al., 1998). In the NO donor SNP, a molecule of NO is coordinated to iron metal forming the square bipyramidal complex with five cyanide anions. Interactions of SNP with reducing agents lead to the formation of NO. In the vascular system, NO release by SNP requires the presence of vascular tissue (Bates et al., 1991; Marks et al., 1995). NO formation from SNP is accompanied by cyanide release (Bates et al., 1991), which can be toxic to the vascular cells. It has also been reported that SNP could be involved in the formation of O2− anions and in consequent peroxynitrite. Due to these toxic effects of SNP, different metallonitrosyl complexes have recently been developed as NO delivery agents such as nitrosyl ruthenium complexes (Wang et al., 2000; Sauaia et al., 2003; Bonventura et al., 2004; Oliveira et al., 2004). These agents have not been used as drug additives to cardioplegic solutions until now.

A new class of compounds with special features is S-nitrosothiols. Low molecular weight S-nitrosothiols such as S-nitrosoglutathione and S-nitrosocysteine have a short half-life in a range of a few seconds, whereas high molecular weight S-nitrosothiols such as S-nitrosoalbumin show a prolonged half-life between 15–20 min in vivo (Hallström et al., 2002). It has been shown that (a) S-nitroso-N-acetyl-DL-penicillamine induces late preconditioning against myocardial stunning and infarction in conscious rabbits (Takano et al., 1998), (b) S-nitrosoglutathione monoethyl ester has protective effects in isolated rat hearts during cardioplegic ischemic arrest (Konorev et al., 1996), (c) S-nitrosoglutathione inhibits platelet activity during coronary angioplasty (Langford et al., 1994) and suppresses increased NOS activity after canine cardiopulmonary bypass (Mayers et al., 1999). In addition, studies have shown that synthetic compounds such as furoxans require thiols for their thiol-mediated generation of NO (Feelisch et al., 1992).

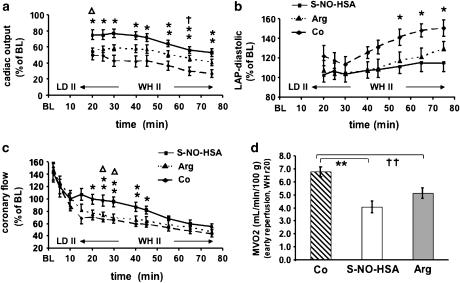

Concerning NO homeostasis and cardioplegia, we are currently working with a new NO-Donor, S-nitroso human serum albumin (S-NO-HSA). This special high molecular weight S-nitrosothiol has an exact equimolar S-nitrosation and high S-nitrosograde due to a defined preprocessing (Hallström et al., 2002). In an experimental setting of 2 h of hindlimb ischemia and reperfusion, Hallström et al. (2002) could show that a supplementation of NO with S-NO-HSA before ischemia or before reperfusion preserves the function of eNOS, stabilizes the basal production of NO, decreases production of reactive oxygen species, and therefore has beneficial effects in reduction of I/R injury. In a second study, simulating clinical cold organ procurement and storage, hearts were reperfused after 6 h of ischemia on an isolated, erythrocyte-perfused working heart model. We could not only show a statistical significant beneficial hemodynamic and metabolic effect of S-NO-HSA compared to control but also compared to supplementation with L-arginine (Semsroth et al., 2005). In Figure 2, we have included data from these experiments. In a third group of experiments, orthotopically transplanted pig hearts underwent 4 h of ischemia followed by 3 h of reperfusion. We observed beneficial hemodynamic and metabolic effects of S-NO-HSA compared to control (Dworschak et al., 2004; Gottardi et al., 2004).

Figure 2.

S-nitroso human serum albumin (S-NO-HSA) attenuates ischemia/reperfusion injury after prolonged cardioplegic arrest in isolated rabbit hearts: in an isolated erythrocyte-perfused rabbit working heart model after assessment of hemodynamic baseline values hearts were randomly assigned to receive S-NO-HSA (0.2 μmol/100ml, n=8), L-arginine (10 mmol/100 ml, n=8) or albumin (control; 0.2 μmol/100 ml, n=8). After 20 min of infusion, the hearts were arrested and stored in Celsior solution (4°C) enriched with respective drugs for 6 h, followed by 75 min of reperfusion. Postischemic recovery of hemodynamic parameters are shown. (a) Time course of cardiac output; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 S-NO-HSA versus control. ΔP<0.05 S-NO-HSA versus L-arginine;†P<0.05 L-arginine versus control. (b) Time course of coronary flow; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 S-NO-HSA versus control. ΔP<0.05 S-NO-HSA versus L-arginine. (c) Time course of left atrial pressure; *P<0.05 S-NO-HSA versus control. (d) Myocardial oxygen consumption; **P<0.01 S-NO-HSA versus control. ††P<0.01 L-arginine versus control. (This figure is from Semsroth et al., 2005: J Heart Lung Transplant 24: 2226–2234© Elsevier Publishing Group with permission.)

Discussion and outlook

Still the supplementation of NO is controversial since there are studies that report negative effects. This might be caused by either different experimental settings, differences in NO donors or different methods of supplementation. In a review, Bolli (2001) concludes that endogenous and exogenous NO is beneficial in protecting the unstressed heart, not preconditioned against damage occurring during I/R. NO plays a critical bifunctional role in late preconditioning, a preconditioning phase that appears 12–24 h after an ischemic stimulus and persists for 72 h. In the latter situation, enhanced production of NO by eNOS is essential to trigger enhanced production of NO by iNOS that is required to mediate the anti-stunning and anti-infarct actions of late preconditioning.

As noted by Vasquez-Vivar et al. (1998) and Huk et al. (1997), the production of NO depends on sufficient supply of its substrate L-arginine and cofactors as BH4. A relative deficiency of L-arginine leads to an ‘uncoupling' of NOS activity with the production of O2− anion instead of NO. It is important to note that if iNOS is expressed in vivo (for example, in sepsis), being independent of calcium and calmodulin, then there is a much higher production of NO. Therefore, iNOS is even more predisposed to deplete substrates and cofactors and to predominantly produce O2−. This circumstance might also explain the deleterious effects of iNOS induction in many experimental settings as for example in a model of transgenic mice transfected with iNOS under the control of a cardiac-specific promotor leading to cardiomyopathy, bradyarrhythmia and sudden cardiac death (Mungrue et al., 2002). Therefore, preservation of NO production during organ storage by either supplementation of L-arginine as the physiologic substrate of eNOS or supplementation of NO via the use of a NO-donor may be beneficial for the subsequent heart transplantation.

In the same review as mentioned above, Bolli (2001) examined the role of NO in modulating the severity of I/R injury. Seventy-three percent of the reviewed studies showed that NO either endogenous or exogenous exert a beneficial effect on myocardial protection against infarction or stunning. Caus et al. (2003) have shown in a heterotopic heart transplant model in the rat with 3 h of ischemia that adding L-arginine to their storage solution had a highly significant beneficial effect on graft function after early reperfusion (1 h after aortic declamping).

Similarly, Schwarzacher et al. (1997) reported that in an experimental model of balloon angioplasty, administration of L-arginine at the site of previous vascular damage resulted in a reduction of endothelial dysfunction and improvement of NO generation. This promising study was performed before the era of drug-eluting stents (DES). The possible clinical implications of simultaneous cardioprotective drug delivery and balloon angioplasty and stenting have been overruled by the development of DES. However, with the current critical discussion on DES and the possible risk of late stent thrombosis (Pfisterer et al., 2006), the approach with simultaneous cardioprotective drug delivery and balloon angioplasty could see an experimental and clinical revival.

Reduced NO bioavailability not only has effects on the endothelium but also on the sarcolemmal membrane of the cardiac myocytes. Xu et al. (2003) could show that sarcolemmal-associated NOS isoforms, nNOS and eNOS, may serve to modulate oxidative stress during ischemia in cardiac muscle and thereby regulate the function of key membrane enzymes including (Na+ + K+)-ATPase with a resulting prevention of calcium overload. Pretreatment with a NO-donor NOC-7 (1-hydroxy-2-oxo-3-(N-3-methyl-aminopropyl)-3-methyl-1-triazene) markedly protected both, sarcolemmal NOS isoforms as well as the function of the (Na++K+)-ATPase during ischemia. The protection was also facilitated by the radical scavenging properties of NO released by NOC-7.

In summary, protection of the endothelium and maintenance of NO homeostasis has been recognized as important concept for myocardial protection and is currently evaluated experimentally and clinically. This review has focused on possible drug additives to cardioplegia, which can influence the impairment of NO bioavailability.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ludwig Boltzmann Gesellschaft, 1010 Vienna, for the continuous support.

Abbreviations

- ACE

angiotensin converting enzyme

- DES

drug-eluting stent

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- I/R

ischemia/reperfusion

- nNOS

neuronal NO synthase

- NO

nitric oxide

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- O2−

superoxide

- BH4

(6R)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Ambrosio G, Flaherty JT, Duilio C, Tritto I, Santoro G, Elia PP, et al. Oxygen radicals generated at reflow induce peroxidation of membrane lipids in reperfused hearts. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:2056–2066. doi: 10.1172/JCI115236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrani M, Gray CC, Smolenski RT, Goodwin AT, London A, Yacoub MH. The effect of L-arginine on myocardial recovery after cardioplegic arrest and ischemia under moderate and deep hypothermia. Circulation. 1997;96 (Suppl 9):II274–II279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H, Hori S, Aramori I, Ohkubo H, Nakashini S. Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding an endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;3458:730–732. doi: 10.1038/348730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma H, Ishikawa M, Sekizaki S. Endothelium–dependent inhibition of platelet aggregation. Br J Pharmacol. 1986;88:411–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balligand JL, Cannon PJ. Nitric oxide synthases and cardiac muscle. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:1846–1858. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.10.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JN, Baker MT, Guerra R, Jr, Harrison DG. Nitric oxide generation from nitroprusside by vascular tissue. Evidence that reduction of the nitroprusside anion and cyanide loss is required. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;42:157–165. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90406-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baue AE. The horror autotoxicus and multiple-organ failure. Arch Surg. 1992;127:1451–1462. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420120085016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter GF, Ebrahim Z. Role of bradykinin in preconditioning and protection of the ischemic myocardium. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:843–854. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, Marshall PA, Freeman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhabra MS, Hopkinson DN, Shaw TE, Hooper TL. Attenuation of lung graft reperfusion injury by a nitric oxide donor. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113:327–334. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilinska M, Maczewski M, Beresewicz A. Donors of nitric oxide mimic effects of ischemic preconditioning on perfusion induced arrhythmias in isolated rat hearts. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996;161:265–271. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1279-6_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolli R. Mechanism of myocardial ‘stunning'. Circulation. 1990;82:723–738. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.3.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolli R. Cardioprotective function of inducible nitric oxide synthase and role of nitric oxide in myocardial ischemia and preconditioning: an overview of a decade of research. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1897–1918. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonventura D, Oliveira FS, Tognioli V, Tedesco AC, da Silva RS. A macrocyclic nitrosyl ruthenium complex is a NO donor that induces rat aorta relaxation. Nitric oxide. 2004;10:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger C, Lüscher TF. Release of endothelin from the porcine aorta. Inhibition by endothelium-derived nitric oxide. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:587–590. doi: 10.1172/JCI114477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady AJ, Warren JB, Poole-Wilson PA, Williams TJ, Harding SE. Nitric oxide attenuates cardiac myocyte contraction. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:H176–H182. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.1.H176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braimbridge MV, Chayen J, Bitensky L, Hearse DJ, Jynge P, Cankovic-Darracott S. Cold cardioplegia or continous coronary perfusion? Report on preliminary clinical experience as assessed cytochemically. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1977;74:900–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretschneider HJ, Hubner G, Knoll D, Lohr B, Nordbeck H, Spieckermann PG. Myocardial resistance and tolerance to ischemia: physiological and biochemical basis. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1975;16:241–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckberg GD. A proposed ‘solution' to the cardioplegic controversy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1979;77:803–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckberg GD, Brazier JR, Nelson RL, Goldstein SM, MyConnell DH, Cooper N. Studies of the effects of hypothermia on regional myocardial blood flow and metabolism during cardiopulmonary bypass. III. Effects of temperature, time, and perfusion pressure in fibrillating hearts. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1977;73:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier M, Pellerin M, Perrault LP, Bouchard D, Page P, Searle N, et al. Cardioplegic arrest with L-arginine improves myocardial protection: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2002;73:837–842. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier M, Pellerin M, Page PL, Searle NR, Martineau R, Caron C, et al. Can L-arginine improve myocardial protection during cardioplegic arrest? Results of a phase I pilot study. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:108–112. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caus T, Desrois M, Izquierdo M, Lan C, LeFur Y, Confort-Gouny S, et al. NOS substrate during cardioplegic arrest and cold storage decreases stunning after heart transplantation in a rat model. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22:184–191. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colagrande L, Formica F, Porta F, Martino A, Sangalli F, AvalLi L, et al. Reduced cytokines release and myocardial damage in coronary artery bypass patients due to L-arginine cardioplegia supplementation. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2006;81:1256–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Nucci G, Gryglewski RJ, Warner TD, Vane JR. Receptor-mediated release of endothelium-derived relaxing factor and prostacyclin from bovine aortic endothelial cells is coupled. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2334–2338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrois M, Sciacky M, Lan C, Cozzone PJ, Bernard M. L-arginine during long-term ischemia: effects on cardiac function, energetic metabolism and endothelial damage. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2000;19:367–376. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(00)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du ZY, Hicks M, Jansz P, Rainer S, Spratt P, Macdonald P. The nitric oxide donor, diethylamine NONOate, enhances preservation of the donor rat heart. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17:1113–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworschak M, Franz M, Hallström S, Semsroth S, Gasser H, Haisjackl M, et al. S-nitroso human serum albumin improves oxygen metabolism during early reperfusion after severe myocardial ischemia. Pharmacol. 2004;72:106–112. doi: 10.1159/000079139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman DT, Watanabe M, Maulik N, Engelman RM, Rousou JA, Flack JE, III, et al. Critical timing of nitric oxide supplementation in cardioplegic arrest and reperfusion. Circulation. 1996;94 (Suppl 9):II407–II411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feelisch M, Schonafinger K, Noack E. Thiol-mediated generation of nitric oxide accounts for the vasodilator action of furoxans. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;44:1149–1157. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90379-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Bianchi C, Sandmeyer JL, Sellke FW. Bradykinin preconditioning improves the profile of cell survival proteins and limits apoptosis after cardioplegic arrest. Circulation. 2005;112:I190–I195. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Li JY, Rosenkranz ER. Bradykinin protects the heart after cardioplegic ischemia via NO-dependent mechanisms. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2000;70:2119–2124. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Sellke ME, Ramlawi B, Boodhwani M, Clements R, Li J, et al. Bradykinin induces microvascular preconditioning through the opening of calcium-activated potassium channels. Surgery. 2006;140:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari R. The role of mitochondria in ischemic heart disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1996;28:1–10. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199600003-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari R, Visioli O. Protective effects of calcium antagonists against ischemia and reperfusion damage. Drugs. 1991;42 (Suppl 1):14–26. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199100421-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa Y, Matsumori A, Hirozane T, Sasayama S. Angiotensin II receptor antagonist TCV-116 reduces graft coronary artery disease and preserves graft status in a murine model. A comparative study with captopril. Circulation. 1996;93:333–339. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg UC, Hassid A. Nitric oxide-generating vasodilators and 8-bromo-cyclic guanosine monophosphate inhibit mitogenesis and proliferation of cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1774–1777. doi: 10.1172/JCI114081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewaltig MT, Kojda G. Vasoprotection by nitric oxide: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55:250–260. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonon AT, Erbas D, Bröijerson A, Valen G, Pernow J. Nitric oxide mediates protective effect of endothelin receptor antagonism during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1767–H1774. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00544.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottardi R, Szerafin T, Semsroth S, Trescher K, Wolner E, Hallström S, et al. S-nitroso-human serum albumin improves organ preservation in orthotopic heart transplantation in the pig J Heart Lung Transplant 200423172(Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Gourine AV, Gonon AT, Pernow J. Involvement of nitric oxide in cardioprotective effect of endothelin receptor antagonist during ischemia–reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H1105–H1112. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace PA. Ischemia–reperfusion injury. Br J Surg. 1994;81:637–647. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griscavage JM, Hobbs AJ, Ignarro LJ. Negative modulation of nitric oxide synthase by nitric oxide and nitroso compounds. Adv Pharmacol. 1995;34:215–234. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)61088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guru V, Omura J, Alghamdi AA, Weisel R, Fremes SE. Is blood superior to crystalloid cardioplegia? A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trails. Circulation. 2006;114:I331–I338. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallström S, Gasser H, Neumayer C, Fügl A, Nanobashvili J, Jakubowski A, et al. S-nitroso human serum albumin treatment reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury in skeletal muscle via nitric oxide release. Circulation. 2002;105:3032–3038. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018745.11739.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman JC. The role of bradykinin and nitric oxide in the cardioprotective action of ACE inhibitors. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:789–792. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00192-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H, Sawabe K, Nakanishi N, Wakasugi OK. Delivery of exogenous tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) to cells of target organs: role of salvage pathway and uptake of its precursor in effective elevation of tissue BH4. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;86 (Suppl 1):2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatori N, Sjöquist PO, Marklund SL, Pehrsson SK, Ryden L. Effects of recombinant human extracellular-superoxide dismutase type-c on myocardial reperfusion injury in isolated cold-arrested rat hearts. Free radical Biol Med. 1992;13:137–142. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90075-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta E, Rubin LE, Seyedi N. Bradykinin and cardioprotection: don't set your heart on it. Pharmacol Res. 1997;35:531–536. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1997.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashida N, Tomoeda H, Oda T, Tayama E, Chihara S, Akasu K, et al. Effects of supplemental L-arginine during warm blood cardioplegia. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;6:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess ML, Manson NH. Molecular oxygen: friend and foe. The role of the oxygen free radical system in the calcium paradox, the oxygen paradox and ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1984;16:969–985. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(84)80011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hishikawa K, Lüscher TF. Pulsatile stretch stimulates superoxide production in human aortic endothelial cells. Circulation. 1997;96:3610–3616. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huk I, Nanobashvili J, Neumayer C, Punz A, Mueller M, Afkhampour K, et al. L-arginine treatment alters the kinetics of nitric oxide and superoxide release and reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury in skeletal muscle. Circulation. 1997;96:667–675. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.2.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignarro LJ, Buga GM, Wood KS, Byrns RE, Chaudhuri G. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor produced and released from artery and vein is nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:9265–9269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahania MS, Sanchez JA, Narayan P, Lasley RD, Mentzer RM., Jr Heart preservation for transplantation: principles and strategies. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:1983–1987. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G, III, Tsao PS, Lefer AM. Cardioprotective effects of authentic nitric oxide in myocardial ischemia with reperfusion. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:244–252. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199102000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski L, Matys T, Chabielska E, Buczko W, Malinski T. Angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonists inhibit platelet adhesion and aggregation by nitric oxide release. Hypertension. 2002;40:521–527. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000034745.98129.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai AJ, Mesaros S, Finkel MS, Oddis CV, Birder LA, Malinski T. Beta-adrenergic regulation of constitutive nitric oxide synthase in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1371–C1377. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitakaze M, Minamino T, Node K, Komamura K, Shinozaki Y, Mori H, et al. Beneficial effects of inhibition of angiotensin-concerting enzyme on ischemic myocardium during coronary hypoperfusion in dogs. Circulation. 1995;92:950–961. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiziltepe U, Tunctan B, Eyileten ZB, Sirlak M, Arikbuku M, Tasoz R, et al. Efficiency of L-arginine enriched cardioplegia and non-cardioplegic reperfusion in ischemic hearts. Int J Cardiol. 2004;97:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein HH, Schubothe M, Nebendahl K, Kreuzer H. The effects of two different diltiazem treatments on infarct size in ischemic reperfused porcine hearts. Circulation. 1984;69:1000–1005. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.69.5.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojda G, Kottenberg K. Regulation of basal myocardial function by NO. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41:514–523. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00314-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller PT, Bergmann SR. Reduction of lipid peroxidation in reperfused isolated hearts by diltiazem. Circ Res. 1989;65:838–846. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.3.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konorev EA, Joseph J, Tarpey MM, Kalyanaraman B. The mechanism of cardioprotection by S-nitrosoglutathione monoethyl ester in rat isolated heart during cardioplegic ischaemic arrest. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:511–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn P, Kröner A, Schirnhofer J, Hallström S, Bernecker O, Mallinger R, et al. Quinaprilar during cardioplegic arrest prevents ischemia–reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124:352–360. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.121676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthuis RJ, Granger DN, Townsley MI, Taylor AE. The role of oxygen – derived free radicals in ischemia induced increases in canine skeletal muscle vascular permeability. Circ Res. 1985;57:599–609. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourembanas S, Marsden PA, McQuillan LP, Faller DV. Hypoxia induces endothelin gene expression and secretion in cultured human endothelium. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1054–1057. doi: 10.1172/JCI115367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kröner A, Seitelberger R, Schirnhofer J, Bernecker O, Mallinger R, Hallström S, et al. Diltiazem during reperfusion preserves high-energy phosphates by protection of mitochondrial integrity. Europ J Cardio Thorac Surg. 2002;21:224–231. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)01110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford EJ, Brown AS, Wainwright RJ, de Belder AJ, Thomas MR, Smith RE, et al. Inhibition of platelet activity by S-nitrosoglutathione during coronary angioplasty. Lancet. 1994;344:1458–1460. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laude K, Thuillez C, Richard V. Coronary endothelial dysfunction after ischemia and reperfusion: a new therapeutic target. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34:1–7. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2001000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar H, Volpe C, Bao Y, Rivers S, Vita JA, Keany JF., Jr Beneficial effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors during acute revascularization. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:487–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linz W, Wiemer G, Schoelkens BA. ACE-inhibition induces NO-formation in cultured bovine endothelial cells and protects ischemic rat hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1992;24:909–919. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(92)91103-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loke KE, McConnell PI, Tuzman JM, Shesely EG, Smith CJ, Stackpole CJ, et al. Endogenous endothelial nitric oxide synthase-derived nitric oxide is a physiological regulator of myocardial oxygen consumption. Circ Res. 1999;84:840–845. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.7.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XL, Weyrich AS, Lefer DJ, Lefer AM. Diminished basal nitric oxide release after myocardial ischemia and reperfusion promotes neutrophil adherence to coronary endothelium. Circ Res. 1993;72:403–412. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinski T, Taha Z. Nitric oxide release from a single cell measurement in situ by a porphyrinic based microsensor. Nature. 1992;358:676–678. doi: 10.1038/358676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks GS, McLaughlin BE, Jimmo SL, Poklewska-Koziell M, Brien JF, Nakatsu K. Time-dependent increase in nitric oxide formation concurrent with vasodilation induced by sodium nitroprusside, 3-morpholinosydnonimine and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine but not by glyceryl trinitrate. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:1125–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayers I, Salas E, Hurst T, Johnson D, Radomski MW. Increased nitric oxide synthase activity after canine cardiopulmonary bypass is suppressed by S-nitrosoglutathione. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:1009–1016. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melrose DG, Dreyer B, Bentall HH, Baker JB. Elective cardiac arrest. Lancet. 1955;269:21–22. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(55)93381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S, Palmer RM, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide: phsiology, pathophsiology and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SD, Yellon DM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors potentiate preconditioning through bradikinin B2 receptor activation in human heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1559–1606. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzel T, Daiber A, Ullrich V, Mülsch A. Vascular consequences of endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling for the activity and expression of the soluble guanylyl cyclase and the cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1551–1557. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000168896.64927.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungrue IN, Gros R, You X, Pirani A, Azad A, Csont T. Cardiomyocyte overexpression of iNOS in mice results in peroxynitrite generation, heart block, and sudden death. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:735–743. doi: 10.1172/JCI13265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SK, Gao B, Bose S, Rizeq M, McCord JM. A novel heparin-binding, human chimeric, superoxide dismutase improves myocardial preservation and protects from ischemia–reperfusion injury. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21:1296–1303. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00461-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira FS, Tognioli V, Pupo TT, Tedesco AC, da Silva RS. Nitrosyl ruthenium complex as nitric oxide delivery agent: synthesis characterization and photochemical properties. Inorg Chem Commun. 2004;7:160–164. [Google Scholar]

- Paulus WJ, Shah AM. NO and cardiac diastolic function. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;43:595–606. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrault LP, Nicker C, Desjardins N, Dumont E, Thai P, Carrier M. Improved preservation of coronary endothelial function with Celsior compared with blood and crystalloid solutions in heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:549–558. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(01)00242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfisterer M, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Buser PT, Rickenbacher P, Hunziker P, Mueller C, Basket-Late Investigators et al. Late clinical events after discontinuation may limit the benefit of drug-eluting stents: an observational study of drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2592–2595. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky DJ, Oz MC, Koga S, Taha Z, Broekman MJ, Marcus AJ, et al. Cardiac preservation is enhanced in a heterotopic rat transplant model by supplementing the nitric oxide pathway. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2291–2297. doi: 10.1172/JCI117230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podesser BK, Schirnhofer J, Bernecker OJ, Kröner A, Franz M, Semsroth S, et al. Optimizing I/R-injury in the failing rat heart improved myocardial protection with acute ACE inhibition. Circulation. 2002;106:I277–1283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podesser BK, Zegner M, Weisser J, Koci G, Kunold A, Hallström S, et al. Vergleich dreier gängiger Kardioplegielösungen-Untersuchungen am isolierten Herz zur Myokardprotektion während Ischämie und Reperfusion. Acta Chirurg Austriaca. 1996;28:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Radomski MW, Palmer RMJ, Moncada S. Endogenous nitric oxide inhibits human platelet adhesion to vascular endothelium. Lancet. 1987;2:1057–1058. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramzy D, Rao V, Mallidi H, Tumiati LC, Xu N, Miriuka S, et al. Cardiac allograft preservation using donor-shed blood supplemented with L-arginine. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1665–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recchia FA, McConnell PI, Loke KE, Xu X, Ochoa M, Hintze TH. Nitric oxide controls cardiac substrate utilization in the conscious dog. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;44:325–332. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redondo J, Manso AM, Pacheco ME, Hernandez L, Salaices M, Marin J. Hypothermic storage of coronary endothelial cells reduces nitric oxide synthase activity and expression. Cryobiology. 2000;41:292–300. doi: 10.1006/cryo.2000.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y, Miyazaki H, Kimura S, Goto K, et al. Cloning of a cDNA encoding a non-isopeptide-selective subtype of the endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:732–735. doi: 10.1038/348732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom J, Carlson L, Marklund SL, Edlund T. The heparin binding domain of extra cellular superoxide dismutase-c and formation of varients with reduced heparin affinity. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18205–18209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauaia MG, de Lima RG, Tedesco AC, da Silva RS. Photoinduced NO release by visible light irradation from pyrazine-bridged nitrosyl ruthenium complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14718–14719. doi: 10.1021/ja0376801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzacher SP, Lim TT, Wang B, Kernoff RS, Niebauer J, Cooke JP, et al. Local intramural delivery of L-arginine enheances nitric oxide generation and inhibits lesion formation after balloon angiplasty. Circulation. 1997;95:1863–1869. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.7.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitelberger R, Hannes W, Gleichauf M, Keilich M, Christoph M, Fasol R. Effects of diltiazem on perioperative ischemia, arrhythmias, and myocardial function in patients undergoing elective coronary bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:811–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellke FW, DiMaio MJ, Caplan LR, Ferguson TB, Gardner TJ, Hiratzka LF, et al. Comparing on-pump and off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Circulation. 2005;111:2858–2864. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.165030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semsroth S, Fellner B, Trescher T, Bernecker OY, Kalinowski L, Gasser H, et al. S-nitroso human serum albumin attenuates ischemia/reperfusion injury after prolonged cardioplegic arrest in isolated rabbit hearts. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:2226–2234. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumway NE, Lower RR, Stofer RC. Selective hypothermia of the heart in anoxic cardiac arrest. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1959;109:750–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegfried MR, Carey C, Ma XL, Lefer AM. Beneficial effects of SPM-5185, a cysteine-containing NO donor in myocardial ischemia–reperfusion. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H771–H777. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.3.H771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöquist PO, Carlson L, Jonason G, Marklund SL, Abrahamson T. Cardioprotective effects of recombinant human extracellular-superoxide dismutase type C in rat isolated heart subjected to ischemia and reperfusion. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1991;17:678–683. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199104000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southard JH. Organ preservation. Ann Rev Med. 1995;46:235–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.46.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternbergh WC, Makhoul RG, Adelman B. Nitric oxide mediated endothelium dependent vasodilatation is selectively attenuated in the postischemic extremity. Surgery. 1993;114:960–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro H, Miyazaki A, Satomura K, Ryden L, Kaul S, Kar S, et al. Infarct size reduction with coronary venous retroinfusion of diltiazem in the acute occlusion/reperfusion porcine heart model. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1996;28:134–141. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199607000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano H, Tang XL, Qiu Y, Guo Y, French BA, Bolli R. Nitric oxide donors induce late preconditioning against myocardial stunning and infarction in conscious rabbits via an antioxidant-sensitive mechanism. Circ Res. 1998;83:73–84. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The GISSI-3 APPI study Group Early and six month outcome in patients with angina pectoris early after acute myocardial infarction (the GISSI-3 APPI study) Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:1191–1197. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trescher K, Bauer M, Dietl W, Gottardi R, Hallström S, Wick N, et al. Improvement of cardioprotection by the selective endothelin-A-receptor antagonist TBC-3214Na: acute versus long-term blockade Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 20065O55-I (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Valantine HA. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: central role of endothelial injury leading to transplant ‘atheroma'. Transplantation. 2003;76:891–899. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000080981.90718.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B, Martasek P, Hogg N, Masters BS, Karoui H, et al. Superoxide generation by endothelial nitric oxide synthase: the influence of cofactors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9220–9225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S, Maitland A, WEisel RD, Fedak PW, Pomroy NC, Li SH, et al. Novel cardioprotective effects of tetrahydrobiopterin after anoxia and reoxygenation: Identifying cellular targets for pharmacologic manipulation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:1074–1083. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.121687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YX, Legzdins P, Poon JS, Pang CC. Vasodilator effects of organotransition–metal nitrosyl complexes, novel nitric oxide donors. J Cardiovascular Pharmacol. 2000;35:73–77. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200001000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis M, Cooke JP. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy and dysregulation of the NO synthase pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:567–575. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000067060.31369.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth KJ, Linz W, Weimer G, Schoelkens BA. Kinins and cardioprotection. Pharmacol Res. 1997;35:527–530. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1997.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CE, Rees DD, Moncada S. Protective and pathological roles of nitric oxide in endotoxin shock. Cardiovasc Res. 1992;26:48–57. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu KK. Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity and gene expression. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;962:122–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Zweier JL. Direct measurement of nitric oxide generation from nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12705–12710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu KY, Kuppusamy SP, Wang JQ, Li H, Cui H, Dawson TM, et al. Nitric oxide protects cardiac sarcolemmal membrane enzyme function and ion active transport against ischemia-induced inactivation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41798–41803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashiro S, Noguchi K, Kuniyoshi Y, Koya K, Sakanashi M. Role of tetrahydrobiopterin on ischemia–reperfusion injury in isolated perfused rat hearts. J Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;44:37–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M, Schmid RA, Ando K, Cooper JD, Patterson GA. Nitroprusside ameliorates lung allograft injury. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62:791–796. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)00439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Tomobe Y, Kobayashi M, Mitsui Y, et al. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1988;332:411–415. doi: 10.1038/332411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahler S, Kupatt CH, Becker BF. ACE inhibition attenuates cardiac cell damage and preserves release of NO in the postischemic heart. Immunopharmacology. 1999;44:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]