Abstract

In recent years, somatic stem cells have been heralded as potential therapeutic agents to address a large number of degenerative diseases. Yet, in order to rationally utilize these cells as effective therapeutic agents, and/or improve treatment of stem-cell-associated malignancies such as leukemias and carcinomas, a better understanding of the basic biological properties of stem cells needs to be acquired. A major limitation in the study of somatic stem cells lies in the difficulty of accessing and studying these cells in vivo. This barrier is further compounded by the limitations of in vitro culture systems, which are unable to emulate the microenvironments in which stem cells reside and which are known to provide critical regulatory signals for their proliferation and differentiation. Given the complexity of vertebrate adult somatic stem cell populations and their relative inaccessibility to in vivo molecular analyses, the study of somatic stem cells should benefit from analyzing their counterparts in simpler model organisms. In the past, the use of Drosophila or C. elegans has provided invaluable contributions to our understanding of genes and pathways involved in a variety of human diseases. However, stem cells in these organisms are mostly restricted to the gonads, and more importantly neither Drosophila, nor C. elegans are capable of regenerating body parts lost to injury. Therefore, a simple animal with experimentally accessible stem cells playing a role in tissue maintenance and/or regeneration should be very useful in identifying and functionally testing the mechanisms regulating stem cell activities. The planarian Schmidtea mediterranea is poised to fill this experimental gap. S. mediterranea displays robust regenerative properties driven by an adult, somatic stem cell population capable of producing the ∼40 different cell types found in this organism, including the germ cells. Given that all known metazoans depend on stem cells for their survival, it is extremely likely that the molecular events regulating stem cell biology would have been conserved throughout evolution, and that the knowledge derived from studying planarian stem cells could be vertically integrated to the study of vertebrate somatic stem cells. Current efforts, therefore, are aimed at further characterizing the somatic population of planarian stem cells in order to define its suitability as a model system in which to mechanistically dissect the basic biological attributes of metazoans stem cells.

Introduction

Advances in human stem cell isolation [1-7] has led to a resurgence of interest in the biology of stem cells. This interest is due, in large part, to the therapeutic potential of stem cells for curing degenerative diseases and repairing injuries. However, before the recent breakthroughs in studies of human stem cells can be effectively and safely applied in the clinic, several fundamental questions about the basic biology of stem cells need to be addressed. How is their proliferation regulated in vivo to generate the appropriate number of daughter stem cells and differentiating progeny? Is there something special in the microenvironment of the stem cell that controls its proliferation and differentiation? How are the developmental potentials of stem cells restricted to a particular fate? How is pluripotentiality maintained and what steps lead to the loss of this pluripotentiality?

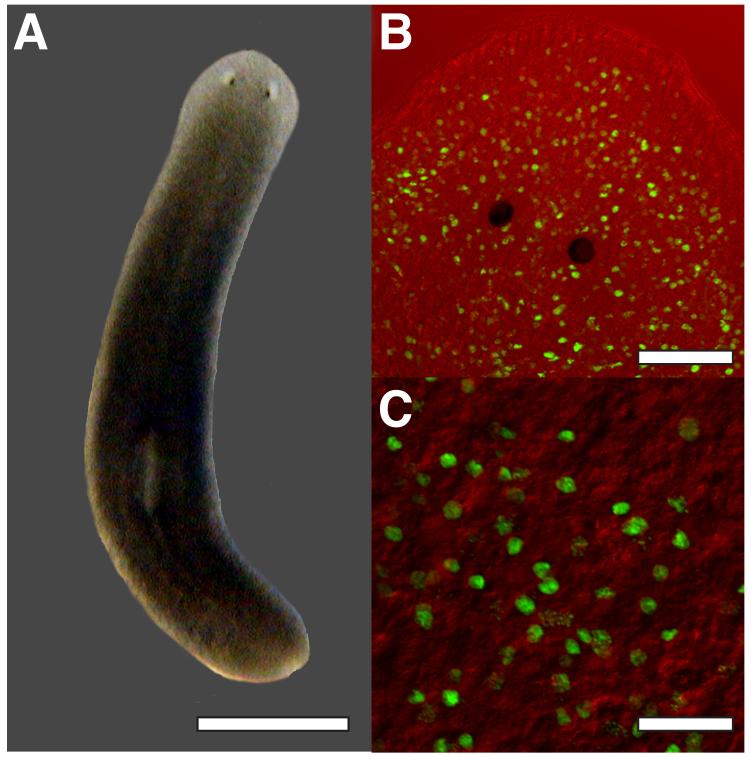

A number of established methodologies and recent technical advances make planarians an excellent model system in which to address these types of questions (Figure 1). A collection of ∼15,000 non-redundant cDNAs are now available, and methods for large-scale, automated, whole-mount in situ hybridization have been established to begin analyzing the spatio-temporal patterns in which these genes are expressed in the animal [8]. We have also shown that double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) can be used to inhibit specifically gene expression in planarians [9]. Furthermore, planarians can be fed an artificial food mixture containing E.coli cells engineered to produce dsRNA [10], resulting in specific gene inhibition as initially described in C. elegans [11, 12]. This technology has greatly expedited large-scale screens for genes that are involved in regenerative processes [13]. Moreover, if planarians are subjected to gamma irradiation (10,000 rads) the organisms lose their neoblasts and their ability to regenerate and survive. In order to take advantage of these tools to study planarian stem cells, it will be necessary to further characterize the cell biology of neoblasts.

Figure 1.

The planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. A) A specimen of the asexual, clonal strain CIW4. B) Labeled neoblasts and their division progeny six days after a single pulse of BrdU. C) Magnification of labeled proliferating neoblasts 8 hours after a single pulse of BrdU (see [16] for experimental details). Scale bars for A, B and C are 1mm, 100μm and 50μm, respectively

The planarian stem cells: the Neoblasts

The term neoblast was first coined by Harriet Randolph in 1892 to describe the small, undifferentiated, embryonic–like cells found in the adult body plan of earthworms [14]. The term was extended to planarians when similar cells were found in their body plan (Figure 1B, C). With respect to studying stem cell biology, the planarian neoblasts can give rise to any part of the worm (in sexual forms, this includes the germ line), regardless of their position in the animal [15]. Given the apparent immortality of asexually reproducing planarian strains, these stem cells also appear to be immortal. Thus, the large and experimentally accessible population of stem cells in planarians [16] should allow for the identification of events leading to aplasias, hypoplasias, dysplasias and myoproliferative disorders in neoblast populations. The recently sequenced S. mediterranea genome and the availability of the human, as well as other vertebrate (mouse and zebrafish) and deuterostome (ascidians and sea urchins) genome sequences will help us determine if what is learned in planarians at the molecular level could be applied to the study of vertebrate stem cell biology and to the treatment of stem cell disorders in humans caused by defects in stem cell maintenance (aniridia), proliferation (leukemias) and differentiation (teratocarcinomas).

Defining the in vivo population dynamics of animal stem cells

We have already shown that the neoblasts are the only proliferating cells in the planarian as they are the only cells that can be labeled specifically with bromodeoxyuridine [16]. In addition, we have generated cDNA libraries from a cell fraction enriched in neoblasts and have begun to identify neoblast-specific genes [17]. These molecular reagents, along with our ability to abrogate gene expression by using RNA-interference (RNAi) have allowed us to begin a delineation of key molecular characteristics of the roles these cells play during both regeneration and tissue homeostasis [13, 18]. However, this information will be truly useful if more knowledge on the behavior of neoblast populations under a variety of conditions were to be acquired.

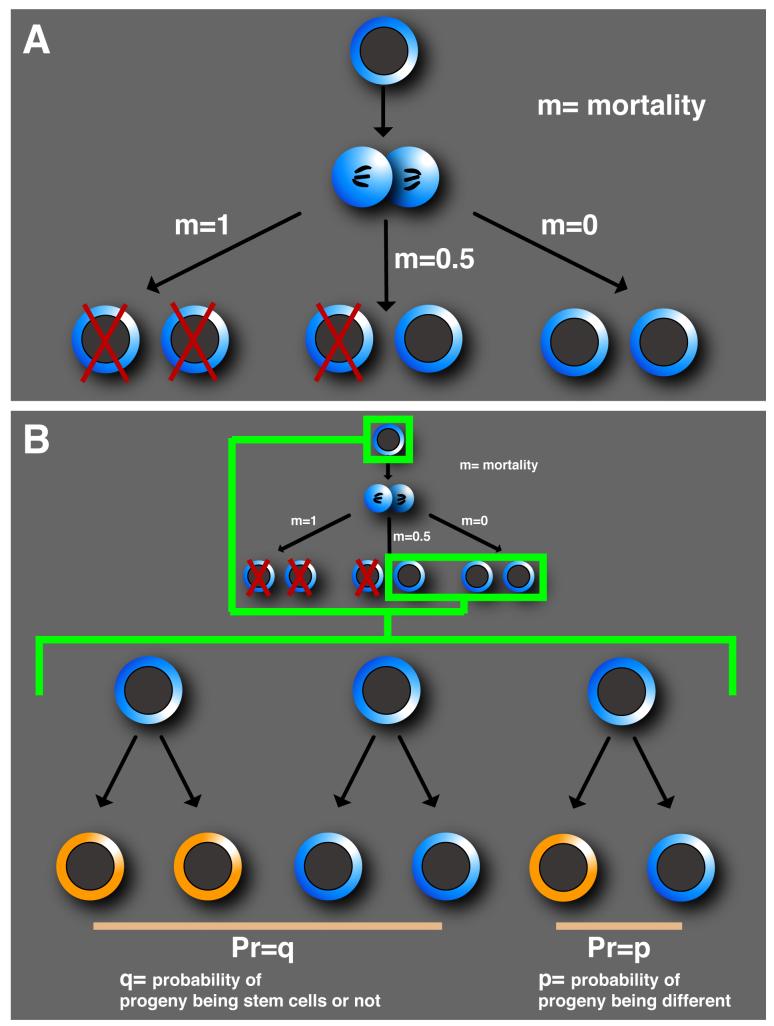

Yet, we know little about the mechanisms by which stem cell populations are regulated in vivo in general, and during growth and regeneration in particular, or how their numbers are maintained during the normal physiological turnover experienced by most tissues. In fact, models for the regulation of the population dynamics of metazoan stem cells have been worked out primarily in vitro (Figure 2). Such models, therefore, suffer of at least the following caveats. First, because of the strong selective pressures imposed by tissue culture on cell survival and their downstream activities, it is difficult to recapitulate in vivo conditions. Second, most available models, therefore, do not allow to distinguish between multiple concurrent processes, e.g., self-renewal and differentiation, likely to be predominant in mixtures of cells with many subpopulations at different stages of differentiation.

Figure 2.

Models of stem cell population dynamics: mortality, proliferation and differentiation of stem cells. A) Probabilistic outcomes of mortality events in effecting regulation of stem cell population numbers. Red crosses indicate death. B) Deterministic and stochastic models of stem cell population dynamics of cells that scape death (boxed in green). The deterministic model posits that a small number of stem cells reside in a niche, each of which divides asymmetrically to produce a stem cell and a transient amplifying cell. Stem cells in this model are, thus, “immortal”. The stochastic model postulates multiple stem cells occupying a niche, and each stem cell division yielding two, one, or no stem cells (or alternatively zero, one, or two proliferating transient amplifying cells). The net result is a ‘‘drift’’ in the numbers of descendants of each stem cell lineage over time [23, 24].

Such lack of knowledge regarding cell population dynamics of stem cells in vivo also extends to the planarian neoblasts. Therefore, defining the molecular characteristics of a metazoan stem cell population such as the planarian neoblasts, in combination with the ability to study its cell behavior in vivo will provide a unique model system for trying to understand how multicellular organisms regulate the pluripotentiality of their cells. Mechanistic insight at both the molecular and cellular level of this fundamental biological property is bound to have deep implications in our understanding of stem cell biology and the rational development of stem-cell-based therapeutic strategies.

Improving the isolation of neoblasts

Until recently [17, 19] the state of the art for neoblast isolation consisted in the dissociation of whole planarians in a medium free of calcium and magnesium, and then serial passage of this cell suspension through Nytex sieves of different pore diameters (160, 100, 60, 40 and 10 μm) [20]. Since neoblasts range between 5-8 μm in diameter, the fraction obtained after passage through the last sieve (10 μm) is rich in neoblasts (∼70%). However this fraction is usually contaminated with a variety of cells (gastric and muscle cells as well as some neurons) that due to their geometry will sometimes pass through the 10 m filter. Agata and colleagues have improved on the methods to purify isolated neoblasts by developing fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) methods suitable for planarian cells [19].

The method takes advantage of irradiation, which is known to eliminate dividing cells (neoblasts, in the case of planarians). Wild type and irradiated planarians are cut into pieces, treated with trypsin and are completely dissociated into single cells by gentle pipetting, and passed through a 40 μm pore-size filter to eliminate aggregated cells. The cell suspension is then stained with propidium iodide to label dead cells for later elimination during sorting. Since no surface-specific antigens are known for planarian neoblasts yet, neoblasts are identified by labeling the dissociated cells of wild type and irradiated animals with Hoechst 323342 blue (stains DNA) and Calcein AM (labels the cytosol of viable cells). The labeled specimens are then subjected to FACS analysis. First, PI-labeled cells are excluded from the samples. The degree of forward-angle light scatter (FSC) is also be used to exclude non-cellular debris and/or any large cells present in the samples. Once debris, and undesired cells are excluded, the samples will be analyzed based on the intensities of DNA and vital dyes (Hoechst 323342 blue, and Calcein AM, for example). By comparing wild type and irradiated planarian samples, two major cell fractions are found missing in the irradiated animals. These correspond to cells which are dividing (X1; DNA content > 2n), and a side population of small cells ranging in size from 6-8 μm in dimaeter (Figure 3). Because of their size and morphology, it is believed that populations X1 and X2 are enriched in neoblasts. Hence, these fractions of cells can be sorted and utilized for downstream applications such as in situ hybridizations [17], RNA and protein isolation, as well as injection into irradiated animals, for example.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence activated cell sorting profiles of planarian cells. In the upper-left plot, Calcein emission is plotted on the X-axis and Hoechst blue on the Y-axis. The analysis gates from which the other 3 plots are sorted are shown in color. The remaining three plots are of the forward (size) and side (granularity) scatter characteristics of the two radiation sensitive populations, X1 and X2, and the radiation resistant cells in Xins. The inset in each of these plots shows representative morphologies of the sorted cells. For all cell insets, scale bar is 10μm.

Conclusions

In recent years, much progress has been made in the identification of molecules associated with the regulation of adult stem cells in mammals [3, 4]. However, the relatively small number of these cells in mammalian tissues and their relative scarcity in traditional invertebrate model systems has hampered progress in our understanding of adult stem cells in animals. We have endeavored to bridge this gap by identifying an invertebrate organism that possesses large numbers of experimentally accessible adult stem cells in which to test large numbers of hypotheses in relatively short periods of time. This organism is the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea a stable diploid with a relatively small (∼700Mbases) and now sequenced genome for which clonal lines (e.g., CIW4) have been developed to reduce naturally occurring variabilities found in wild type populations and thus standardize the study of its biology. We have also introduced the necessary methods to study the stem cells of these organisms at high levels of functional resolution. Hence, it is now possible to measure biological processes in planarians [21], catalog genes and visualize their expression[22], as well as to specifically and robustly interfere with their functions [13].

Because S. mediterranea is composed of a large number of stem cells (neoblasts) yet possess a relatively small number of differentiated cell types, it has now become possible to embark on a systematic in vivo analysis of the population dynamics of this adult stem cell population. It is our expectation that much will be learned soon from these studies not only about the neoblasts themselves, but also about the evolutionarily conserved cellular and molecular mechanisms that must regulate the maintenance, function and differentiation of stem cells in multicellular organisms.

Acknowledgements

I thank Mr. & Mrs. Kurt and Ilse Piotrowski for support during the preparation of this manuscript; Dr. Kiyokazu Agata for sharing sorting protocols; Mr. James Jenkin for assisting with FACS experiments; all other members of my laboratory for discussions; and NIH NIGMS RO-1 GM57260 and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute for funding.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bjornson CR, Rietze RL, Reynolds BA, Magli MC, Vescovi AL. Turning brain into blood: a hematopoietic fate adopted by adult neural stem cells in vivo. Science. 1999;283:534–537. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5401.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark LD, Clark RK, Heber-Katz E. A new murine model for mammalian wound repair and regeneration. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;88:35–45. doi: 10.1006/clin.1998.4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Yilmaz OH, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim I, He S, Yilmaz OH, Kiel MJ, Morrison SJ. Enhanced purification of fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells using SLAM family receptors. Blood. 2006;108:737–744. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, Henegariu O, Hwang S, Gardner R, Neutzel S, Sharkis SJ. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shamblott MJ, Axelman J, Wang S, Bugg EM, Littlefield JW, Donovan PJ, Blumenthal PD, Huggins GR, Gearhart JD. Derivation of pluripotent stem cells from cultured human primordial germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13726–13731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Elder J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiegiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarado A. Sánchez, Newmark P, Robb SMC, Juste R. The Schmidtea mediterranea database as a molecular resource for studying platyhelminthes, stem cells and regeneration. Development. 2002 doi: 10.1242/dev.00167. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarado A. Sánchez, Newmark PA. Double-stranded RNA specifically disrupts gene expression during planarian regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:5049–5054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newmark PA, Reddien PW, Cebria F, Alvarado A. Sánchez. Ingestion of bacterially expressed double-stranded RNA inhibits gene expression in planarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(Suppl 1):11861–11865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834205100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Timmons L, Court DL, Fire A. Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene. 2001;263:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Timmons L, Fire A. Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature. 1998;395:854. doi: 10.1038/27579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddien PW, Bermange AL, Murfitt KJ, Jennings JR, Alvarado A. Sánchez. Identification of genes needed for regeneration, stem cell function, and tissue homeostasis by systematic gene perturbation in planaria. Dev Cell. 2005;8:635–649. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Randolph H. The regeneration of the tail in lumbriculus. J. Morphol. 1892;7:317–344. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddien PW, Alvarado A. Sánchez. Fundamentals of planarian regeneration. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:725–757. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.095114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newmark P, Alvarado A. Sánchez. Bromodeoxyuridine specifically labels the regenerative stem cells of planarians. Dev Biol. 2000;220:142–153. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddien PW, Oviedo NJ, Jennings JR, Jenkin JC, Alvarado A. Sánchez. SMEDWI-2 is a PIWI-like protein that regulates planarian stem cells. Science. 2005;310:1327–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.1116110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newmark PA. Opening a new can of worms: a large-scale RNAi screen in planarians. Dev Cell. 2005;8:623–624. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi T, Asami M, Higuchi S, Shibata N, Agata K. Isolation of planarian X-ray-sensitive stem cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Dev Growth Differ. 2006;48:371–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2006.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baguñá J, Saló E, Auladell C. Regeneration and pattern formation in planarians. III. Evidence that neoblasts are totipotent stem cells and the source of blastema cells. Development. 1989;107:77–86. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oviedo NJ, Newmark PA, Alvarado A. Sánchez. Allometric scaling and proportion regulation in the freshwater planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Dev Dyn. 2003;226:326–333. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvarado A. Sánchez, Newmark PA, Robb SM, Juste R. The Schmidtea mediterranea database as a molecular resource for studying platyhelminthes, stem cells and regeneration. Development. 2002;129:5659–5665. doi: 10.1242/dev.00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ro S, Rannala B. Methylation patterns and mathematical models reveal dynamics of stem cell turnover in the human colon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10519–10521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201405498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viswanathan S, Davey RE, Cheng D, Raghu RC, Lauffenburger DA, Zandstra PW. Clonal evolution of stem and differentiated cells can be predicted by integrating cell-intrinsic and-extrinsic parameters. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2005;42:119–131. doi: 10.1042/BA20040207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]