Brodmann’s area 44 delineates part of Broca’s area within the inferior frontal gyrus of the human brain and is a critical region for speech production1,2, being larger in the left hemisphere than in the right1–4 — an asymmetry that has been correlated with language dominance2,3. Here we show that there is a similar asymmetry in this area, also with left-hemisphere dominance, in three great ape species (Pan troglodytes, Pan paniscus and Gorilla gorilla). Our findings suggest that the neuroanatomical substrates for left-hemisphere dominance in speech production were evident at least five million years ago and are not unique to hominid evolution.

To our knowledge, no one has assessed whether there is any consistent left–right anatomical asymmetry in the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) of any non-human primate. This is surprising because it is known from cytoarchitectonic and electrical stimulation studies that many non-human primates, including the great apes5,6, possess a homologue of area 44. We have therefore investigated whether homologous neuro-anatomical asymmetries are present in area 44 in great apes.

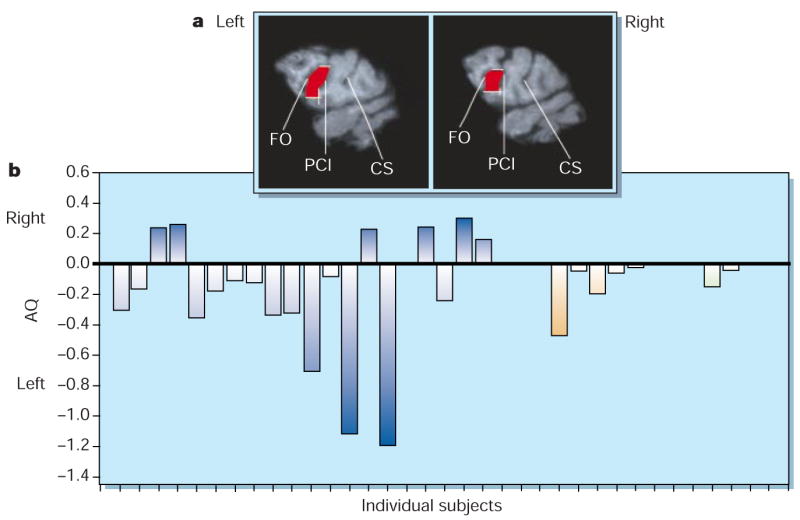

From magnetic resonance images (MRI) obtained from 20 chimpanzees (P. troglodytes), 5 bonobos (P. paniscus) and 2 gorillas (G. gorilla; Fig. 1a), we found that area 44 in these species shows a pattern of morphological asymmetry that has left-hemisphere surface-area predominance similar to the homologous cortical area of humans (mean left, 127.7 mm2±8.1 s.e.; mean right, 104.2 mm2±6.1 s.e.; F(1,25) = 7.45, P=0.011; see supplementary information for details of the statistical analysis, and see Fig. 1b for individual asymmetry measures). In humans, this region is part of Broca’s area, a key anatomical substrate for speech functions, particularly in motor aspects of speech such as articulation and fluency2,7.

Figure 1.

Asymmetry of Brodmann’s area 44 in great apes. a, Area 44 (shown in red in the two hemispheres of a chimpanzee brain), which is defined as the portion of cortical surface of the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) bounded by the fronto-orbital (FO) and precentral-inferior (PCI) sulci (CS, central sulcus). Both the FO and PCI sulci can be seen in parasagittal (1 mm thick) slices obtained using magnetic resonance imaging. The dorsal and ventral borders of area 44 are marked in white. We base the definition of the ventral border on cytoarchitectonic studies that show area 44 expanding over the ventral extent of the IFG, even if the PCI sulcus usually terminates at a more dorsal level5,6. b, Individual asymmetry quotients (AQ; calculated as (R−L)/[(R+L)×0.5], where R and L represent areas in the right and left regions, respectively; the sign of the quotient indicates the direction of asymmetry: positive, right-hemisphere asymmetry; negative, left-hemisphere asymmetry) in individual chimpanzees ((blue bars), bonobos (orange) and gorillas (green). On the basis of criteria used for humans3, 20 apes showed left-hemisphere asymmetry, six showed right-hemisphere asymmetry and one had no asymmetry (χ2(2) = 21.56, P<0.001). The number of subjects with a left-hemisphere asymmetry was greater than the number of subjects with either right-hemisphere asymmetry (z=2.55, P=0.011) or no asymmetry (z=4.15, P<0.001).

The part possession by great apes of a homologue of Broca’s area is puzzling, particularly considering the discrepancy between sophisticated human speech and the primitive vocalizations of great apes. This may be explained by the contribution that gestures have made to the evolution of human language and speech8. In monkeys, the so-called ‘mirror neurons’ in area 44 seem to subserve the imitation of hand grasping and manipulation, and this neural system may have been specialized initially for gestural and later for vocal communication9. In captive great apes, manual gestures are both referential and intentional10,11, and are preferentially produced by the right hand (which is controlled by the left hemisphere). This right-hand bias is consistently greater when gesturing is accompanied by vocalization10.

From an evolutionary standpoint, therefore, asymmetry in area 44 may be associated with the production of gestures accompanied by vocalizations in great apes, an ability that eventually selected for the development of speech systems in modern humans and perhaps generated more cortical folding in the IFG, leading to expansion of Brodmann’s area 45 in the human brain.

Whatever the function of area 44 in great apes, our finding that these species show a human-like asymmetry not only in posterior (such as the planum temporale12,13) but also in frontal regions, indicates that the origin of asymmetry in language-related areas of the human brain should be interpreted in evolutionary terms rather than being confined to the human species.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplementary information accompanies this communication on Nature’s website (www.nature.com).

References

- 1.Galaburda AM. In: Cerebral Dominance: The Biological Foundations. Geschwind N, Galaburda AM, editors. Harvard Univ. Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1984. pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foundas AL, Eure KF, Luevano LF, Weinberger DR. Brain Lang. 1998;64:282–296. doi: 10.1006/brln.1998.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amunts K, Schleicher A, Bürgel U, Mohlberg H, Uylings HB, Zilles K. J Comp Neurol. 1999;412:319–341. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990920)412:2<319::aid-cne10>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broca P. Bull Soc Anat Paris. 1861;2:330–357. [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Bonin G. In: The Precentral Motor Cortex. Bucy PC, editor. Univ. Illinois Press; Urbana-Champaign: 1949. pp. 7–82. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey P, von Bonin G, McCulloch WS. The Isocortex of the Chimpanzee. Univ. Illinois Press; Urbana-Champaign: 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luria AR. Traumatic Aphasia. Mouton; The Hague: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corballis MC. Cognition. 1992;44:197–226. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(92)90001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizzolatti G, Arbib MA. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:188–194. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopkins WD, Leavens DA. J Comp Psychol. 1998;112:95–99. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.112.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hostetter AB, Cantero M, Hopkins WD. J Comp Psychol. doi: 10.1037//0735-7036.115.4.337. (in the press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gannon PJ, Holloway RL, Broadfield DC, Braun AR. Science. 1998;279:220–222. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopkins WD, Marino L, Rilling JK, MacGregor LA. NeuroReport. 1998;9:2913–2918. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199808240-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.