Abstract

The standard treatment for tinea capitis caused by Microsporum species for many years has been oral griseofulvin, which is no longer universally marketed. Voriconazole has been demonstrated to inhibit growth of Microsporum canis in vitro. We evaluated the efficacy and tissue pharmacokinetics of oral voriconazole in a guinea pig model of dermatophytosis. Guinea pigs (n = 16) were inoculated with M. canis conidia on razed skin. Voriconazole was dosed orally at 20 mg/kg/day for 12 days (days 3 to 14). The guinea pigs were scored clinically (redness and lesion severity) and mycologically (microscopy and culture) until day 17. Voriconazole concentrations were measured day 14 in blood, skin biopsy specimens, and interstitial fluid obtained by microdialysis in selected animals. Clinically, the voriconazole-treated animals had significantly less redness and lower lesion scores than untreated animals from days 7 and 10, respectively (P < 0.05). Skin scrapings from seven of eight animals in the voriconazole-treated group were microscopy and culture negative in contrast to zero of eight animals from the untreated group at day 14. The colony counts per specimen were significantly higher in samples from untreated animals (mean colony count of 28) than in the voriconazole-treated animals (<1 in the voriconazole group [P < 0.0001]). The voriconazole concentration in microdialysate (unbound) ranged from 0.9 to 2.0 μg/ml and in the skin biopsy specimens total from 9.1 to 35.9 μg/g. In conclusion, orally administered voriconazole leads to skin concentrations greater than the necessary MICs for Microsporum and was shown to be highly efficacious in an animal model of dermatophytosis. Voriconazole may be a future alternative for treatment of tinea capitis in humans.

Dermatophytes are keratinophilic fungi that infect tissue containing keratin such as hair, nails, and skin. Dermatophytes consist of three genera: Microsporum, Trichophyton, and Epidermophyton. Microsporum species, with Microsporum canis predominating, are frequent causes of scalp ringworm, tinea capitis, in Europe (9). M. canis is zoophilic and can be transmitted to humans during close contact with an infected animal, mainly cats and, to a lesser extent, dogs. Other Microsporum species, e.g., M. audouinii and its variants M. langeronii and M. rivalieri, are anthropophilic, and infections are transmitted between humans, sometimes causing epidemics (9). Tinea capitis primarily affects children (3).

Oral griseofulvin has long been the standard treatment of tinea capitis; however, this agent has been withdrawn from the market in several countries in Europe. Alternative antifungal agents have been suggested: itraconazole, which is not universally licensed for the treatment of children (7, 10); fluconazole, which in most comparative studies appears to be less effective when M. canis is involved and which is not approved for tinea capitis in the United States (8); and finally terbinafine, which again is less efficient in Microsporum than in Trichophyton infections (6). Although there is no standardized method for susceptibility testing of dermatophytes, studies using modifications of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI; formerly the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards) methodology have shown voriconazole to be active against dermatophytes, including Microsporum species, with MICs in the range of 0.01 to 2 μg/ml (5, 13). We therefore sought to investigate the pharmacokinetics and in vivo efficacy of voriconazole in a guinea pig model of M. canis dermatophytosis. Skin biopsy specimens, whole blood, and samples obtained by microdialysis (from infected and uninfected skin) were collected in order to measure the total concentrations of voriconazole and the unbound fraction to correlate this with in vivo efficacy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

The experiments were approved by the Animal Experiments Inspectorate under the Danish Ministry of Justice (number 2003/561-868). Eighteen female guinea pigs (Hsd.Poc:DH; Harlan Netherlands, Horst, The Netherlands) weighing 418 to 482 g were used. Due to the risk of transmitting the infection by Microsporum spores from infected skin scales to other animals in the animal stable, the experiments were carried out under biosafety level (BSL) 3 conditions. The food and stable conditions were as prescribed for BSL 3.

Preparation of inoculum.

A clinical isolate of M. canis was incubated at 25°C on Sabouraud glucose agar (SAB) with cycloheximide and chloramphenicol (SSI Diagnostica, Hillerød, Denmark) for 3 weeks. The fungal cells were harvested by floating the colonies with 12 ml of sterile water mixed with 2 drops of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) containing 0.01% Tween 20 (SSI Diagnostica), followed by gentle agitation with a single-use sterile pipette. Macroconidia and large hyphal elements were removed by filtration (Nylon Net Filters, pore size 11 μm; Millipore, Carrigtwohill, Ireland); the number of microconidia was counted in a hemacytometer and adjusted to approximately 8 × 105 conidia/ml. The viability of the conidia was confirmed by growth on SAB.

Antifungal susceptibility testing.

The MIC was determined according to the CLSI M38-A method procedure with the following modifications. The inoculum used was 105 CFU/ml, and the incubation was done at 25°C for 10 days (11). Determinations were performed in triplicates, and the MIC was determined to be 0.25 μg/ml.

Anesthesia.

Guinea pigs were anesthetized by intramuscular administration of a combination anesthetic containing Zoletil 50 Vet (Zolazepam [125 mg] and Tiletamin [125 mg]; Virbac S.A., Carros, France), Xylazin Vet (20 mg/ml; Intervet International B.V., Boxmeer, The Netherlands), and Torbugesic Vet (Butorphanol [10 mg/ml]; Fort Dodge Veterinaria S.A., vall de Bianya, Spain). The guinea pigs were anesthetized before inoculation, voriconazole dosing, and specimen collection. Neutral Vaseline ointment was used to prevent cornea damage.

Infection model.

Sixteen guinea pigs (n = 8 in the voriconazole group and n = 8 in the untreated control group) were clipped and shaved with a single-use manual razor (Zorrik twin blades; Super-Max., Ltd., Feltham, United Kingdom) at five areas at the flanks and back to prepare the inoculation. Shaving traumatizes the skin and makes it more susceptible to infection (17). Portions (50 μl) of fungal suspension (8 × 105 conidia/ml) were used to inoculate four of the five ring areas on each guinea pig. The areas were margined by a Vaseline ring and measured 1.5 cm in diameter. The guinea pigs were evaluated clinically on days 3, 7, 10, 14, and 17 by the same person. The clinical evaluation consisted of a semiquantitative score where the inoculated areas were evaluated and compared to the uninfected ring area on the back of the same animal. The redness score was graduated as follows: 0, normal; 1, pink; 2, red; and 3, violet. The lesion score was graduated as follows: 0, normal; 1, papule; 2, skin scales; 3, single layer of skin scales and ulcers; and 4, multiple layers skin scales and ulcers. Examples of clinical scores are shown in Fig. 1. Areas that had been used for prior specimen sampling were excluded for subsequent clinical evaluation to avoid bias by redness and ulcers due to prior scraping. Mycological examinations were performed on days 3, 7, 14, and 17. The specimens were taken according to routine standards for obtaining material for dermatomycological examinations using a sterile sharp spoon for scraping and forceps for the collection of hair (12). Sampling was done after disinfection with 70% isopropyl alcohol and 0.5% chlorohexidine (OY Teampac AB, Helsinki, Finland) in order to remove superficial residual fungal elements from the previously applied inoculum. One of the four inoculation ring areas per animal was used on each occasion of sampling. The entire ring area (diameter of 1.5 cm) was scraped; however, the amount of material varied depending on the severity of the lesion (amount of hair, scales, and crust). In the case of no visual lesion, 20 to 30 hairs were obtained and the skin scraped. The specimens were placed between two glass slides and wrapped in paper. Half of the material was subsequently used for direct microscopy and the other half for culture. Direct examination was performed in 20% KOH (SSI Diagnostica) by using a light (phase) microscope. Microscopy was positive when hyphae, arthroconidia, and/or conidia were detected. Cultures were incubated on SAB with cycloheximide and chloramphenicol (SSI Diagnostica) for 28 days and evaluated weekly. M. canis is considered a true pathogen, and a positive culture is significant for the diagnosis of dermatophytosis. The numbers of colonies (i.e., CFU) per specimen were noted, and identification to the species level was done according to the method of Campell et al. (2). Lactophenol Cottonblue-Phenol+Ethanol (SSI Diagnostica) was used for coloring the material before microscopy. Negative controls of hair were used to test the possibility of contaminating the specimens in the laboratory.

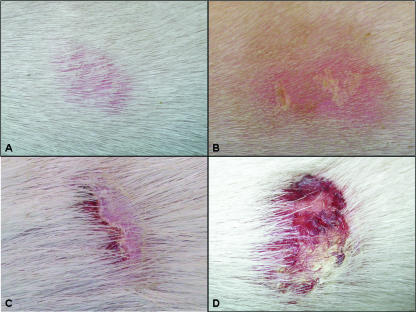

FIG. 1.

Examples of clinical scores: A, redness score (RS) pink and lesion score (LS) normal; B, RS pink, LS skin scales; C, RS pink, LS one layer skin scales and ulcers; D, RS red, LS multiple skin scales and ulcers.

Treatment.

Animals in the treatment group received voriconazole oral solution (purchased from Pfizer, Ballerup, Denmark) by gavage tube in a dose of 20 mg/kg/day (0.3 ml) for 12 days (days 3 to 14). Animals in the control group were left untreated.

Microdialysis procedure.

The three first numbers of the treated guinea pigs were included in the pharmacokinetic part of the study day 14. The animals underwent surgery in general anesthesia. Skin channels were made in the dermis by penetrating uninfected (normal) and inoculated skin by a cannula with diameters of 1.2 and 1.65 mm (BD Microlance; BD Drogheda, Ireland). CMA 70 microdialysis brain catheters with an outer diameter of 0.9 mm (CMA/Microdialysis, Solna, Sweden) were placed in the channels and CMA 107 microdialysis infusion pumps were connected. The positions of the catheters were controlled by visual inspection of the dermal channel by autopsy. The tissue was allowed to recover for 30 min after the insertion trauma before starting the experiment. Flow rates were set to 1 μl/min, and isotonic NaCl solution was chosen as the perfusate. Prior to the voriconazole administration, in vivo relative recovery of voriconazole was attained in every guinea pig. This was done according to the retrodialysis method as previously published (19) in order to calibrate the probe. For this, two premanufactured concentrations (5 and 10 μg/ml) of voriconazole (intravenous solution, purchased from Pfizer) were added to the perfusate. The in vivo relative recovery was calculated as follows: RR (%) = [1 − (Cdialysate/Cperfusate)] × 100, where Cdialysate is the outlet concentration (μg/ml) and Cperfusate is the inlet concentration of voriconazole (μg/ml). The unbound tissue concentration was defined as Ctissue = 100 × Cdialysate × RR−1.

Time zero was defined as the end of the administration of voriconazole (20 mg/kg/day, the twelfth dose). Microdialysates were collected every 30 min over a period of 3 h.

Blood samples and skin biopsy specimens.

Blood samples were obtained from the eye vein and collected hourly beginning 1 h after voriconazole administration. Full-thickness 3-mm skin punch biopsy specimens (Produkte für die Medizin AG, Cologne, Germany) were collected from the margin of the inoculated area hourly.

Voriconazole concentration determinations in serum, skin biopsy, and interstitial fluid samples. (i) Chemicals.

Voriconazole for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analyses was provided by Pfizer Global Research and Development (Sandwich Kent, USA) and was used under isocratic conditions with a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Acetonitrile (HPLC gradient grade) was purchased from Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany), ammonia (30%) was from Gruessing (Filsum, Germany), and ammonium dihydrogen phosphate was from Fluka Chemie AG (Neu-Ulm, Germany).

(ii) HPLC.

HPLC experiments were performed by using an HPLC system (JASCO, Gross-Umstadt, Germany) with UV detection at 254 nm. Samples were separated on a LiChrospher-100 RP-18 (5 μm, 125-by-4-mm column with an integrated precolumn (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) as the stationary phase. The mobile phase consisted of an acetonitrile-ammonium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0; 0.04 M; 46:54 [vol/vol]) and was used under isocratic conditions with a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The lower and upper limits of quantification of voriconazole were 0.2 and 10 μg/ml, respectively.

(iii) Sample preparation.

Microdialysates, retrodialysis, and probe calibration solution samples were transferred from the microdialysis microvials into safe-lock tubes. After a simple one-step dilution of microdialysates with acetonitrile at the ratio 40 to 60 (vol/vol) and vortexing (Microshaker Type 326; Premed, Warsaw, Poland), a volume of 20 μl was injected into the HPLC system. Whole-blood samples were prepared by a two-in-one step preparation procedure. Precipitation of proteins and dilution were performed by mixing a 50-μl aliquot with 75 μl of acetonitrile. The mixtures were vortexed and centrifuged at 13,500 × g for 15 min (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5417R; Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). Then, 30 μl of the clear supernatant was injected into the HPLC system. Biopsy samples were extracted with acetonitrile-ammonium phosphate buffer (0.04 M, 60:40 [vol/vol]) for 6 h at room temperature under continuous shaking. Five freeze-thaw cycles with liquid nitrogen were performed during the first hour in order to force extraction of the skin. After the extraction procedure the samples were centrifuged at 13,500 × g for 10 min, and 35 μl of the supernatant was injected into the HPLC system.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed by using PC SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). A Wilcoxon two-sample test was used to compare the VCZ group to the control group with respect to clinical scores and colony counts per assessment time. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Clinical results.

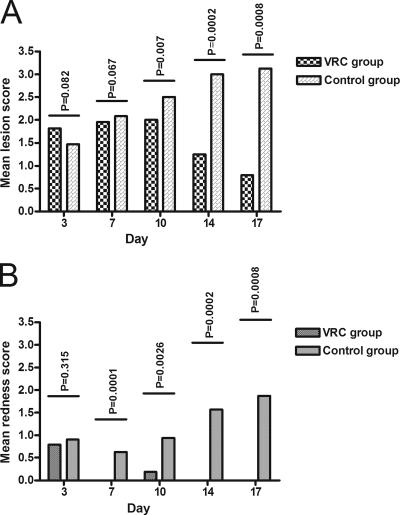

All animals showed clinical signs of infection day 3; however, in three animals in the voriconazole group one of four inoculation sites was clinically uninfected. These areas were therefore excluded from further evaluations. The clinical scores are shown in Fig. 2A (lesion severity) and B (skin redness). As expected, no significant differences were observed between animals in the two groups on day 3 when treatment was initiated. Redness score and lesion score were significantly less severe in the voriconazole-treated animals than in untreated animals on days 7 and 10 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Clinical score in eight voriconazole-treated and eight untreated animals, respectively. (A) Lesion score (0, normal; 1, papule; 2, skin scales; 3, single layer of skin scales and ulcers; 4, multiple layers of skin scales and ulcers). (B) Redness score (0, normal; 1, pink; 2, red; 3, violet). The results are indicated as the means of the inoculated areas of all of the animals in each of the groups. Areas previously used for mycological sampling were excluded. Days 3 and 7 consist of four areas per animal, days 10 and 14 consist of three areas per animal, and day 17 consists of two areas per animal. Scores were compared between the two groups for each observation day, and the P values (Wilcoxon test) are shown above the columns.

Mycological results.

Prior to treatment a significant difference in colony counts was observed between the two animal groups, since cultures from animals in the voriconazole group yielded higher colony counts than those in the untreated control group (P = 0.023, Table 1). During treatment (days 7 and 14), skin scrapings from animals in the voriconazole-treated group yielded significantly fewer colonies than scrapings from the control group. This effect was retained until the end of the study 3 days after the last dose, at which point the mean colony counts were <1 versus 25.5 in the control group (P = 0.002, Table 1). Similarly, the number of microscopy- and culture-negative animals was higher in the voriconazole-treated group (eight of eight animals were microscopy negative and seven of eight animals were culture negative) than in the control group (0 of 8 animals were microscopy and/or culture negative).

TABLE 1.

Microscopy and culture results from the voriconazole-treated animals and an untreated positive control group over time

| Group | Animal no. | Detection at daya:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3

|

7

|

14

|

17

|

||||||

| M | CC | M | CC | M | CC | M | CC | ||

| Voriconazole-treated animals | 3072 | + | 9 | - | 7 | - | 0 | ND | ND |

| 3073 | - | 0 | + | 6 | - | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 3074 | - | 8 | - | 6 | - | 0 | ND | ND | |

| 3076 | + | 13 | + | 3 | - | 0 | - | 0 | |

| 3078 | - | 3 | - | 3 | - | 0 | - | 0 | |

| 3079 | + | 1 | - | 3 | - | 0 | - | 0 | |

| 3080 | + | 8 | + | 5 | - | 0 | - | 1 | |

| 3081 | + | 9 | - | 0 | - | 2 | - | 0 | |

| Mean | 6.4 | 4.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |||||

| Control animals | 3082 | + | 2 | + | 16 | + | 23 | + | 21 |

| 3083 | - | 2 | + | 16 | + | 38 | + | 13 | |

| 3084 | - | 0 | + | 17 | + | 33 | + | 28 | |

| 3085 | - | 0 | + | 29 | + | 22 | + | 16 | |

| 3086 | + | 3 | + | 8 | + | 26 | + | 45 | |

| 3087 | + | 3 | + | 19 | + | 39 | + | 25 | |

| 3088 | - | 0 | + | 25 | + | 21 | + | 30 | |

| 3089 | + | 0 | + | 12 | + | 22 | + | 26 | |

| Mean | 1.3 | 17.8 | 28 | 25.5 | |||||

M, microscopy, CC, colony count per specimen; +, hyphae and/or arthroconidia detected, −; no fungal elements; ND, not done. Treatment was initiated on day 3. Animals 3072 to 3074 were sacrificed day 14 (enrolled in the pharmacokinetic study). The P values, representing the differences in colony counts between the untreated control and the treated groups of animals, were 0.023, <0.001, <0.001, and 0.002 for days 3, 7, 14, and 17, respectively.

Voriconazole concentration determinations in whole blood, skin biopsy specimens, and interstitial fluid.

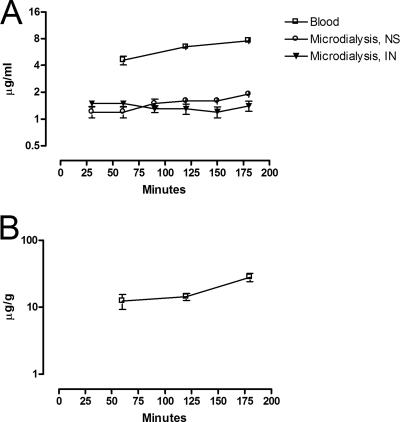

The voriconazole concentration in blood, microdialysate, and biopsy specimens during the 3-h sampling period is presented in Fig. 3. A notably high concentration was achieved in skin (mean Cmax 28.1 μg/g; range, 23.6 to 35.9 μg/g). The mean maximal concentration in blood was 7.6 μg/ml (range, 7.6 to 7.7 μg/ml) and in microdialysate was 1.7 μg/ml (range, 1.1 to 2.0 μg/ml). During the entire investigation, the average and minimum and maximum concentrations were 18.3 μg/g and 9.1 to 35.9 μg/g for skin biopsy specimens, 6.3 μg/ml and 4.0 to 7.7 μg/ml for whole blood, and 1.4 μg/ml and 0.9 to 2.0 μg/ml for microdialysates, respectively (Table 2).

FIG. 3.

Voriconazole concentrations in interstitial fluid (microdialysis) and blood (A) and in skin biopsy specimens (B) after the twelth dose (20 mg/kg/day). NS, normal skin; IN, inoculated skin. The results are presented as means ± the SD.

TABLE 2.

Voriconazole concentrations in whole blood, microdialysates, and skin biopsy samples over the whole sampling time (3 h)

| Value | Voriconazole concn in:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole blood (μg/ml) | Microdialysate (μg/ml) | Skin biopsy sample (μg/g) | |

| Mean | 6.3 | 1.4 | 18.3 |

| Minimum | 4.0 | 0.9 | 9.1 |

| Maximum | 7.7 | 2.0 | 35.9 |

The peak concentration did not seem to have been reached in either of the two compartments—blood or skin—during the 3-h sampling period since concentrations were still increasing. Concentrations in the interstitial fluid (the microdialysate samples) varied between 0.9 to 2.0 μg/ml and 0.9 to 1.7 μg/ml in normal and inoculated skin, respectively. This finding indicates that the unbound concentrations of free voriconazole in tissue interstitial fluids were not influenced by inflammation (Fig. 3A).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we demonstrated a significant clinical efficacy of oral voriconazole against M. canis dermatophytosis. Skin redness and lesion severity scores were significantly reduced and continued to decline in contrast to the progressive infection observed in the untreated animals throughout the 17-day observation period. This effect was confirmed by mycological examination since only one animal in the treatment group was culture positive (one residual colony) at the end of the study. Finally, there was no recurrence of the dermatophytosis 3 days after the last dose of voriconazole treatment. Although a direct comparison of the efficacy of voriconazole and other licensed compounds would require additional studies, the cure rate demonstrated in the present study was comparable to that reported in previous studies with a shorter (14) and similar (1) treatment duration. Even though we found an overall agreement between microscopy and culture results, it was surprising that the microscopy appeared less sensitive than cultures, since the opposite is true for examinations of dermatophytosis in humans. Although we cannot completely rule out that samples from uninfected areas may have been contaminated during sampling with a few but viable conidia, the risk of this was minimized by prior disinfection with alcohol prior to specimen collection. A more likely explanation may be the difference in the nature of human and guinea pig skin; human but not guinea pig skin has a very thick nonvascularized keratin layer in which nonviable dermatophytes may be detected more easily.

Voriconazole has been demonstrated to possess in vitro activity against dermatophytes (5, 13), with MICs for Microsporum spp. in general (M. canis, M. gypseum, M. cookei, M. distortum, M. audouinii, and M. nanum) of between 0.01 and 2 μg/ml (5, 13) and for M. canis specifically in the range of 0.01 to 0.5 μg/ml. In the present study we found an average concentration of non-protein-bound voriconazole in microdialysate fluid of 1.4 μg/ml (mean Cmax = 1.7 μg/ml; range, 1.1 to 2.0 μg/ml) in the 3-h observation period after dosing the twelfth day of treatment. The concentration of voriconazole in the microdialysate was four times lower than in blood but still above the MIC of the M. canis isolate (0.25 μg/ml). Furthermore, the concentration in skin biopsy specimens was notably high, as illustrated by a mean concentration of 18.3 μg/g. Although these concentrations cannot be directly compared, the data demonstrate an accumulation in the skin that cannot be explained by protein binding solely. Such accumulation has been described for other compounds in this drug class (4, 18). Itraconazole and fluconazole have been shown to accumulate in stratum corneum of the skin and fluconazole has been shown to be incorporated into the keratin structures of epidermal adnexa, where it can be detected months after the cessation of the treatment (4, 18, 20). This accumulation of itraconazole and fluconazole is thought to contribute to the eradication of the dermatophyte infection and to the fact that pulse therapy including weeks without treatment is effective. Future studies are warranted to elucidate the nature and time course of the voriconazole accumulation in the skin.

We did not find any difference between the voriconazole concentrations measured in microdialysates from normal and infected skin areas. This was probably due to the fact that the infection was almost healed at this time. Thus, we cannot rule out that an ongoing infection with inflammation may influence voriconazole concentration in interstitial fluid. A possible difference might have been found, if the pharmacokinetic experiment had been performed at an earlier stage of the infection. Furthermore, the fact that the concentrations did not vary considerably during the sample period may be explained by the multiple dosing previously.

The levels of voriconazole were still increasing 3 h after dosing in whole-blood and skin biopsy specimens, indicating that the peak concentration was not reached yet. This is in concordance with a study by Roffey et al. (16), who showed an increasing voriconazole blood concentration in guinea pigs during an 8-h period after a single oral dosing. The plasma concentration typically peaks earlier than 2 h postadministration in humans (15), and this discrepancy may at least in part be due to decreased gastrointestinal absorption during anesthesia.

In conclusion, we showed here the efficacy of oral voriconazole for treating dermatophytosis caused by M. canis in a guinea pig model. Furthermore, HPLC measurements of voriconazole concentrations in whole blood, microdialysates from skin, and especially skin biopsy specimens were in the range or higher than the MICs previously published for M. canis. These findings indicate that voriconazole may be a future alternative to griseofulvin for the treatment of tinea capitis in humans.

Acknowledgments

The excellent technical assistance of Dorothea Frenzel in HPLC analysis, the staff from the animal stable, and the mycology laboratory are gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Anders Mørup Jensen for statistical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borgers, M., B. Xhonneux, and J. Van Cutsem. 1993. Oral itraconazole versus topical bifonazole treatment in experimental dermatophytosis. Mycoses 36:105-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell, C. K., E. M. Johnson, C. M. Philpot, and D. W. Warnock. 1996. Identification of pathogenic fungi. Public Health Laboratory Service, London, England.

- 3.Elewski, B. E. 2000. Tinea capitis: a current perspective. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 42:1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faergemann, J., and H. Laufen. 1993. Levels of fluconazole in serum, stratum corneum, epidermis-dermis (without stratum corneum) and eccrine sweat. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 18:102-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandez-Torres, B., A. J. Carrillo, E. Martin, P. A. Del, M. K. Moore, A. Valverde, M. Serrano, and J. Guarro. 2001. In vitro activities of 10 antifungal drugs against 508 dermatophyte strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2524-2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleece, D., J. P. Gaughan, and S. C. Aronoff. 2004. Griseofulvin versus terbinafine in the treatment of tinea capitis: a meta-analysis of randomized, clinical trials. Pediatrics 114:1312-1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginter-Hanselmayer, G., J. Smolle, and A. Gupta. 2004. Itraconazole in the treatment of tinea capitis caused by Microsporum canis: experience in a large cohort. Pediatr. Dermatol. 21:499-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta, A. K., S. L. Hofstader, P. Adam, and R. C. Summerbell. 1999. Tinea capitis: an overview with emphasis on management. Pediatr. Dermatol. 16:171-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hay, R. J., W. Robles, G. Midgley, and M. K. Moore. 2001. Tinea capitis in Europe: new perspective on an old problem. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 15:229-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez-Gomez, S., P. A. Del, C. J. Van, C. M. Soledad, L. Iglesias, and A. Rodriguez-Noriega. 1994. Itraconazole versus griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea capitis: a double-blind randomized study in children. Int. J. Dermatol. 33:743-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2002. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. Approved standard M38-A(22). National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 12.Nelson, M. M., A. G. Martin, and M. P. Heffernan. 2003. Superficial fungal infections: dermatophytosis, onychomycosis, tinea nigra, piedra, p. 1989-2001. In I. M. Freedberg, A. Z. Eisen, K. Wolff, K. F. Austen, L. A. Goldsmith, and S. I. Katz (ed.), Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., New York, NY.

- 13.Perea, S., A. W. Fothergill, D. A. Sutton, and M. G. Rinaldi. 2001. Comparison of in vitro activities of voriconazole and five established antifungal agents against different species of dermatophytes using a broth macrodilution method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:385-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petranyi, G., J. G. Meingassner, and H. Mieth. 1987. Activity of terbinafine in experimental fungal infections of laboratory animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 31:1558-1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purkins, L., N. Wood, K. Greenhalgh, M. J. Allen, and S. D. Oliver. 2003. Voriconazole, a novel wide-spectrum triazole: oral pharmacokinetics and safety. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 56(Suppl. 1):10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roffey, S. J., S. Cole, P. Comby, D. Gibson, S. G. Jezequel, A. N. Nedderman, D. A. Smith, D. K. Walker, and N. Wood. 2003. The disposition of voriconazole in mouse, rat, rabbit, guinea pig, dog, and human 2. Drug Metab. Dispos. 31:731-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saunte, D. M., J. P. Hasselby, N. Frimodt-Møller, D. Linnemann, E. L. Svejgaard, M. Haedersdal, and M. C. Arendrup. 2006. Experimental dermatophytosis in guinea pigs: establishing and evaluating an animal model, abstr. P0132. Sixteenth Congress of the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology, Paris, France.

- 18.Sobue, S., K. Sekiguchi, and T. Nabeshima. 2004. Intracutaneous distributions of fluconazole, itraconazole, and griseofulvin in Guinea pigs and binding to human stratum corneum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:216-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stolle, L. B., M. Arpi, P. Holmberg-Jorgensen, P. Riegels-Nielsen, and J. Keller. 2004. Application of microdialysis to cancellous bone tissue for measurement of gentamicin levels. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:263-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wildfeuer, A., J. Faergemann, H. Laufen, G. Pfaff, T. Zimmermann, H. P. Seidl, and P. Lach. 1994. Bioavailability of fluconazole in the skin after oral medication. Mycoses 37:127-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]