Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection can persist despite HCV-specific T-cell immunity and can have a more aggressive course in persons coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). Defects in antigen-presenting, myeloid dendritic cells (DCs) could underlie this T-cell dysfunction. Here we show that monocyte-derived DCs from persons with chronic HCV infection, with or without HIV-1 coinfection, being treated with combination antiretroviral therapy produced lower levels of interleukin 12 (IL-12) p70 in response to CD40 ligand (CD40L), whereas the expression of DC surface activation and costimulatory molecules was unimpaired. The deficiency in IL-12 production could be overcome by addition of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) with CD40L, resulting in very high, comparable levels of IL-12 production by DCs from HCV- and HIV-1-infected subjects. Smaller amounts of IL-12 p70 were produced by DCs treated with the immune modulators tumor necrosis factor alpha and IL-1β, with or without IFN-γ, and the amounts did not differ among the uninfected and infected subjects. Blocking of IL-10 with an anti-IL-10 monoclonal antibody in the CD40L-stimulated DC cultures from HCV-infected persons increased the level of IL-12 p70 production. The ability of DCs from HCV-infected persons to stimulate allogeneic CD4+ T cells or induce IL-2, IL-5, or IL-10 in a mixed lymphocyte reaction was not impaired. Thus, myeloid DCs derived from persons with chronic HCV infection or with both HCV and HIV-1 infections have defects in IL-12 p70 production related to IL-10 activity that can be overcome by treatment of the DCs with CD40L and IFN-γ. DCs from these infected subjects have a normal capacity to stimulate CD4+ T cells. The functional effectiveness of DCs derived from HCV-infected individuals provides a rationale for the DC-based immunotherapy of chronic HCV infection.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major public health problem, with nearly 3% of the world's population persistently infected with the virus (40). There is accumulating evidence for a central role of adaptive immunity directed by CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in the control of HCV infection and liver disease (4, 37). In about 15 to 20% of the cases, the resolution of acute HCV infection and clearance of the virus are associated with T-cell immunity to various HCV proteins. HCV infection persists, however, in most infected individuals, which is associated with variable, residual HCV-specific cellular immune responses and chronic HCV infection in the liver. Moreover, persons coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) can have a more aggressive course of liver disease (46). This is of particular concern, in that control of HIV-1 infection with combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) can have little effect on the progressive, severe liver disease caused by chronic HCV infection.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells that provide a critical link between innate and adaptive T-cell immunity (45). In this regard, decreases in circulating myeloid and plasmacytoid DC number and function have been documented in patients with chronic HCV infection (1, 18, 30, 51) and in persons with HCV and HIV-1 coinfection (1). In contrast to these findings, information from the few studies of DCs derived from the monocytes of persons with chronic HCV infection show normal levels of interleukin 12 (IL-12) production and the induction of an allogeneic mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR) (22, 35, 44). This and encouraging studies of DC immunotherapy in HCV models of mice (8, 19, 50, 52, 53) support the proposed use of DCs for the immunotherapy of persons with chronic HCV infection (10, 15, 21), similar to the use of antigen-loaded, monocyte-derived DCs for the therapy of HIV-1 infection (24).

The capacity of monocyte-derived DCs to activate T-cell immunity depends on their state of activation (45). Immunomodulating factors that induce optimal DC activation include the CD40 ligand (CD40L) on activated CD4+ T cells (34) and various proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β (39a) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (28). The activation of DCs is manifested as increases in the expression of surface molecules involved in the interaction with T cells, e.g., major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and costimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86, CD83), and the production of T-cell-stimulating cytokines, such as IL-12, followed by a maturation process associated with the reduction or the loss of the IL-12-producing function (16, 20). IL-12 polarizes CD4+ T cells by enhancing Th1-cell production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) rather than enhancing Th2-cell production of cytokines, which in turn enhances antigen-specific, CD8+ T-cell reactivity. The IL-15 produced by DCs is also considered important for the maintenance of memory CD8+ T-cell responses (36). Anti-inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-10, are potent inhibitors of IL-12 production by DCs and can thereby impede Th1 polarization and CD8+ T-cell responses (7). Thus, the decrease in T-cell reactivity during HCV infection could potentially be reversed by treatment with DCs that have been engineered with immunomodulating factors that enhance CD8+ and Th1-cell functions but not Th2-cell functions. However, comprehensive studies that have directly compared the effects of immunomodulators on the function of monocyte-derived DCs from HCV-monoinfected, HCV- and HIV-1-coinfected, and HIV-1-monoinfected subjects with the effects of those from virus-negative control subjects have not been conducted. In the present study, we therefore investigated the effects of chronic HCV infection, with or without HIV-1 infection, on the ability of DCs to respond to activation stimuli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects.

The study population consisted of 35 uninfected donors, 9 HCV-infected and HIV-1-uninfected subjects, 16 HCV-uninfected and HIV-1-infected subjects, and 10 HCV- and HIV-1-coinfected subjects enrolled in the Pittsburgh portion of the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (Table 1), a study of the natural history of HIV infection, based on their availability to participate in this immunologic study. The HCV-infected subjects were not receiving IFN-α treatment during this study. The HIV-1-infected subjects were receiving ART. T-cell counts were determined by flow cytometry, and HIV-1 RNA loads were assayed by PCR, as described previously (13). HCV RNA in serum was quantified by PCR (COBAS AMPLICOR Monitor HCV assay, version 2.0; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) (5). The levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were determined by UV space kinetics (Quest Diagnostic).

TABLE 1.

Virologic and immunologic characteristics of the four study groups

| Characteristic | Value for the following group:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV negative, HIV-1 negative | HCV positive, HIV-1 negative | HCV negative, HIV-1 positive | HCV positive, HIV-1 positive | |

| No. of subjects | 35 | 9 | 16 | 10 |

| CD4 counts (no. of cells/ml) | 898 ± 25 | 938 ± 60 | 691 ± 47a | 438 ± 33b |

| % CD4 | 45 ± 0.7 | 48 ± 2.3 | 34 ± 1.5a | 31 ± 1.6a |

| CD8 counts (no. of cells/ml) | 589 ± 32 | 494 ± 50c | 900 ± 60b | 655 ± 39 |

| % CD8 cells | 28 ± 0.8 | 26 ± 2.3 | 44 ± 1.8a | 49 ± 2.1a |

| CD3 counts (no. of cells/ml) | 1,508 ± 50 | 1,440 ± 87 | 1,583 ± 78 | 1,095 ± 64b |

| % CD3 cells | 75 ± 0.6 | 70 ± 2.8 | 78 ± 1.2 | 77 ± 1.4 |

| ALT level (U/liter) | 25 ± 2 | 59 ± 4d | 26 ± 1.7 | 52 ± 6d |

| No. of subjects infected with HCV genotype 1/2/not done | NAe | 7/1/1 | NA | 9/0/1 |

| No. of HCV RNA copies/ml | NA | (1.81 ± 0.86) × 106f | NA | (1.18 ± 0.28) × 106 |

| No. of HIV-1 RNA level copies/ml | NA | NA | 2,555 ± 900f | 23,019 ± 17,260 |

P < 0.05 compared to the results for the two HIV-negative groups.

P < 0.01 compared to the results for the other three groups.

P < 0.05 compared to the results for the two HIV-positive groups.

P < 0.01 compared to the results for the two HCV-negative groups.

NA, not applicable.

P > 0.05 compared to the results for the HCV- and HIV-positive group.

Generation of DCs.

Monocyte-derived DCs were obtained from CD14+ blood monocytes to a purity of >97%, as described previously (13). The DCs were cultured for 5 to 6 days in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 1,000 U/ml of recombinant IL-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and 1,000 U/ml recombinant granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor (Amgen, Seattle, WA). The DCs were treated with CD40L (1 μg/ml; Amgen) or IL-1β (10 ng/ml; R&D Systems), TNF-α (50 ng/ml; BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA), and IFN-γ (1,000 U/ml; R&D Systems) for 40 h. The activation status of the DCs was determined by flow cytometry as the percent positive and the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of cells expressing HLA class II (HLA-DR), HLA class I (HLA-ABC), CD83, CD86, and CD209. In some experiments, an anti-IL-10 monoclonal antibody (MAb) or an immunoglobulin G (IgG) control (0.1 μg/ml; R&D Systems) was added on day 5 to block IL-10 production.

IL-12 p70 and p40, IL-15, and IL-10 production by DCs.

Supernatants from untreated, matured, and polarization factor-treated DC cultures were collected at 0, 4, 24, and 48 h. These samples were frozen at −70°C for later assay of IL-12 p70 and p40, IL-15, and IL-10 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems). To rule out an effect of the FCS in the cultures on DC function (25), we found in preliminary studies that cytokine production was similar for DCs cultured in serum-free AIM V medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS (data not shown).

Allogeneic MLR and IL-2, IL-5, and IL-10 production.

The MLR is a vigorous, short-term proliferation of naïve T cells that can be activated by the MHC-antigen determinants on allogeneic DCs. For this assay, CD4+ T cells enriched by negative selection with anti-CD8 MAb-coated magnetic microbeads (Stem Cell Technologies) were stimulated in 96-well plates for 5 days with graded numbers of allogeneic DCs that had been treated with different activation factors. The assays were performed in triplicate wells. The cells were harvested after they were labeled with 0.5 μCi/well of [3H]thymidine (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Irvine, CA) for the final 16 h, and the radioactivity was measured with a scintillation counter (Topcount; Packard, Meriden, CT). Supernatants were also harvested at 24 h and frozen at −70°C for later assessment of IL-2, IL-5, and IL-10 production by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems). To compare the effects of treatment of the cells with an anti-IL-10 MAb on IL-12 production, we calculated the percent change in IL-12 p70 production between the non-IL-10 MAb-treated and the anti-IL-10 MAb-treated groups.

Statistical analysis.

Comparisons were done by Student's t test or paired t test. The data among the different cohorts were analyzed by analysis of variance with a Scheffe multiple-comparison test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Basic laboratory parameters for study subjects.

We assessed the blood of the four groups of subjects for various immunologic and virologic parameters that are related to the control of HCV and HIV-1 infections. As expected, both groups of subjects with chronic HCV infection, with or without HIV-1 coinfection, had twofold higher levels of serum ALT than uninfected or HIV-1-infected persons and an average of 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 HCV RNA copies per ml of serum (Table 1). The subjects were infected with the predominant North American HCV genotype, genotype 1, with only one HCV-positive/HIV-1-negative subject infected with genotype 2 and none of the subjects infected with genotype 3. The two groups infected with HIV-1 and receiving ART had similar, low levels of HIV-1 in their blood.

The numbers and percentages of CD4+ T cells were lower and those of CD8+ T cells higher for the two HIV-1-positive groups on long-term ART, most of whom had suppressed HIV-1 viremia (Table 1). Dual HCV and HIV-1 infection can delay the recovery of CD4+ T cells during treatment with ART (11). However, we did not find an association between the length of time that the subjects had been treated with ART at the time of our immunologic testing (data not shown).

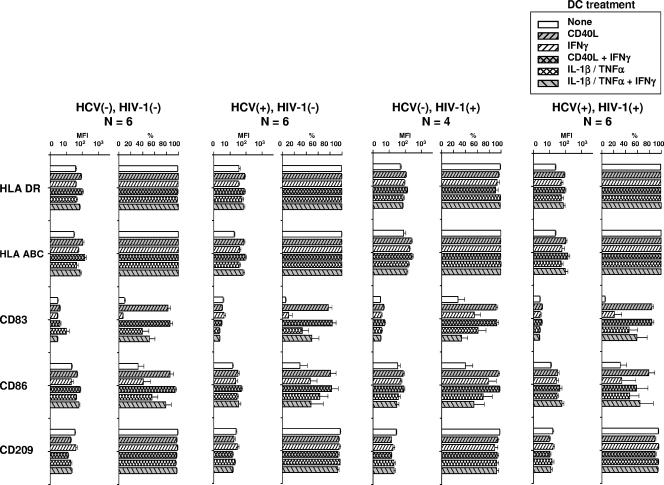

Effect of HCV and HIV-1 infection on DC phenotypic markers.

The DCs were examined by flow cytometry for surface markers related to activation and costimulation. Immature DCs derived from the blood monocytes of the four groups of study subjects did not differ in their expression (MFI or percent positive) of the surface MHC markers HLA DR or HLA ABC or of CD83, CD86, or CD209, which are involved in antigen-specific T-cell activation (Fig. 1). After treatment of the DCs from the various study subjects with either of the two activation factors, CD40L or IL-1β-TNF-α, there was a similar enhancement of the MFI for HLA DR and HLA ABC and of the MFI and the percent positivity for CD83 and CD86, with lower levels of MFI expression for CD209. The results of treatment of the DCs with either activation factor combined with IFN-γ were similar to those of treatment without IFN-γ. These results indicate that chronic HCV infection, with or without HIV-1 coinfection, or that HIV-1 infection alone that is being controlled by ART has no demonstrable effects on the expression of surface molecules on immature and mature DCs that are related to T-cell activation.

FIG. 1.

Effect of HCV and HIV-1 infection of DCs and treatment with CD40L and inflammatory cytokines on expression of DC phenotypic markers. The data are the means ± standard errors for MFI and DCs expressing the various markers. P was not significant within the DC treatments for the five DC markers compared across the four groups of study subjects. HCV(−), HCV negative; HIV-1(−), HIV-1 negative; HCV(+), HCV positive; HIV-1(+), HIV-1 positive.

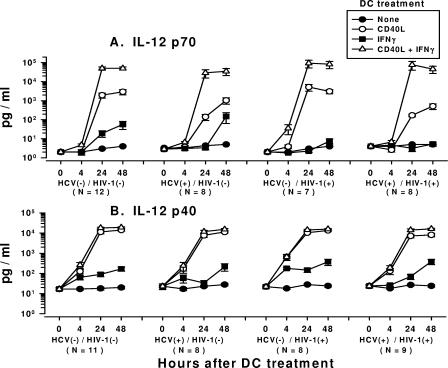

Effects of CD40L and IFN-γ on production of IL-12 p70 and p40 by DCs from HCV- and HIV-1-infected subjects.

We next examined DCs from the various study groups for the production of IL-12. Nonactivated, immature DCs from all four groups of subjects did not produce IL-12 p70 (< 10 pg/ml). In contrast, activation of the DCs with CD40L alone induced comparable, peak levels of several thousand pg/ml of IL-12 p70 by 24 to 48 h in DCs from HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative and HCV-negative/HIV-1-positive subjects (Fig. 2A). However, the DCs from persons with chronic HCV infection, with or without HIV-1 coinfection (HCV-positive/HIV-1-negative and HCV-positive/HIV-1-positive subjects), produced at 24 h smaller amounts of IL-12 p70 (100 to 200 pg/ml), which peaked at 48 h, than the DCs from the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative persons or the HCV-negative/HIV-1-positive subjects.

FIG. 2.

Production of IL-12 p70 (A) and IL-12 p40 (B) by CD40- and CD40L-IFN-γ-treated DCs from HCV- and HIV-1-infected subjects and virus-negative controls. The data are mean ± standard error levels (pg/ml) of IL-12 p70 and p40 production by DCs in response to the treatments shown. (A) Analysis within each group showed that DCs from the four groups of subjects that were treated with either CD40L or CD40L-IFN-γ produced more IL-12 p70 than untreated DCs at 24 h and 48 h (P < 0.05). DCs that were treated with CD40L-IFN-γ produced larger amounts of IL-12 p70 than DCs treated with CD40L for the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative and HCV-negative/HIV-1-positive groups at 24 h and for all four groups at 48 h (P < 0.05). Analysis across the four groups showed that the levels of IL-12 p70 produced by DCs treated with CD40L from the HCV-positive/HIV-1-negative and HCV-positive/HIV-1-positive groups were lower than the levels produced by the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative and HCV-negative/HIV-1-positive groups (P < 0.05). The levels of IL-12 p70 produced by DCs treated with CD40L-IFN-γ were comparable among the four groups of study subjects (P was not significant). (B) Analysis within each group showed that DCs from the four groups of subjects that were treated with either CD40L or CD40L-IFN-γ produced more IL-12 p40 than untreated DCs at 24 h and 48 h (P < 0.05). DCs from all of the groups that were treated with CD40L produced larger amounts of IL-12 p40 than IL-12 p70 at 24 h and 48 h (P < 0.05). DCs from all of the groups that were treated with CD40L-IFN-γ produced larger amounts of IL-12 p40 than DCs treated with CD40L at 24 h and 48 h (P < 0.001). Analysis across the four groups showed that the levels of IL-12 p40 produced by DCs treated with CD40L were higher at 48 h for the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative group than for the HCV-positive/HIV-1-positive group (P < 0.03) but not for the other two groups (P was not significant). The levels of IL-12 p40 produced by DCs treated with CD40L-IFN-γ were comparable among the four groups of study subjects at 24 h and 48 h (P was not significant). HCV(−), HCV negative; HIV-1(−), HIV-1 negative; HCV(+), HCV positive; HIV-1(+), HIV-1 positive.

Treatment of DCs from all four groups of study subjects with CD40L induced high levels of the IL-12 p40 subunit over time (Fig. 2B), and these levels were also higher than the levels of IL-12 p70 (Fig. 2A). However, in contrast to IL-12 p70 production, the levels of IL-12 p40 produced by DCs treated with CD40L were comparable among the four groups, except that a smaller amount of IL-12 p40 was produced by DCs from the HCV-positive/HIV-1-positive group at 48 h. Thus, the lower levels of biologically active IL-12 p70 produced by CD40L-treated DCs from the two groups of HCV-infected persons were not related to the amounts of the inducible IL-12 p40 subunit produced by these DCs.

Stimulation with IFN-γ alone induced low levels of IL-12 p70 (<10 to 150 pg/ml) in DCs from the four groups (Fig. 2A). The level of production of IL-12 p40, however, was greater than that of IL-12 p70 in cultures of IFN-γ-stimulated DCs from all four groups (Fig. 2B).

Stimulation of the DCs with CD40L-IFN-γ resulted in the most potent production of IL-12 p70, i.e., 30,000 to 100,000 pg/ml, by 24 to 48 h in all four groups of study subjects and eliminated the differences among the HCV-infected and uninfected groups seen with treatment with CD40L alone (Fig. 2A). The levels of IL-12 p70 produced by stimulation of DCs with CD40L-IFN-γ were 20- to 50-fold greater than the levels produced by CD40L-treated DCs from the uninfected and HCV-negative/HIV-1-positive subjects and up to 900-fold greater than the levels produced by DCs from both groups of HCV-infected subjects (Fig. 2A). Treatment of the DCs from the four groups of study subjects with CD40L-IFN-γ resulted in larger amounts of IL-12 p40 than the amounts produced by DCs treated with CD40L, and the amounts were comparable across the four groups of study subjects (Fig. 2B).

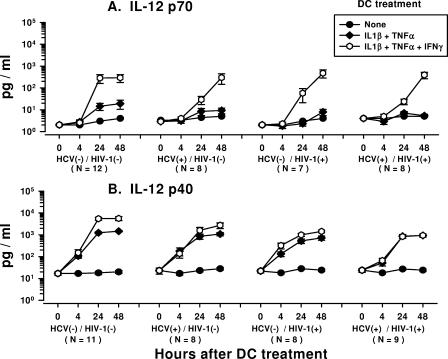

Effects of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ on production of IL-12 p70 and p40 by DCs from HCV- and HIV-1-infected subjects.

Treatment of DCs with IL-1β-TNF-α induced very low levels of IL-12 p70 (20 pg/ml) within each group of study subjects (Fig. 3A). In contrast, treatment of DCs with IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ induced larger amounts of IL-12 p70 over time. The peak response in the production of IL-12 p70 by DCs treated with IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ was at 24 h for the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative group, whereas it was at 48 h for the three virus-infected groups; and the amount produced was larger than the amount of IL-12 p70 produced by IL-1β-TNF-α-treated or untreated DCs at these time points. Notably, there was no difference in the levels of IL-12 p70 production by DCs across the four groups of study subjects that were treated with either IL-1β-TNF-α or IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ.

FIG. 3.

Production of IL-12 p70 (A) and IL-12 p40 (B) by IL-1β-TNF-α- and IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ-treated DCs from HCV- and HIV-1-infected subjects and virus-negative controls. The data are the mean ± standard error levels (pg/ml) of IL-12 p70 and p40 production by DCs in response to the treatments shown. (A) Analysis within each group showed that the treatment of DCs from the four groups of subjects with IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ but not IL-1β-TNF-α increased the levels of IL-12 p70 production at 24 h and 48 h compared to that at 0 h (P < 0.05). IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ-treated DCs from the four groups produced more IL-12 p70 than IL-1β-TNF-α-treated or untreated DCs at 48 h (P < 0.05). Analysis across the four groups showed that the levels of IL-12 p70 produced by DCs treated with IL-1β-TNF-α or IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ were comparable at 24 h and 48 h (P was not significant). (B) Analysis within each group showed that DCs from the four groups of subjects that were treated with either IL-1β-TNF-α or IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ produced more IL-12 p40 at 24 h and 48 h than at 0 h (P < 0.05). DCs from all of the groups that were treated with IL-1β-TNF-α or IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ produced larger amounts of IL-12 p40 than IL-12 p70 at 24 h (P < 0.05). DCs from the study groups that were treated with IL-1β-TNF-α or IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ produced larger amounts of IL-12 p40 compared to the amounts produced by untreated DCs at 24 h and 48 h (P < 0.05), except for DCs from the HCV-negative/HIV-1-positive group at 24 h and 48 h (P was not significant). DCs from the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative and HCV-negative/HIV-1-positive groups treated with IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ produced more IL-12 p40 than DCs treated with IL-1β-TNF-α at 24 h and 48 h (P < 0.01). Analysis across the four groups showed that the levels of IL-12 p40 produced by DCs from the HCV-negative/HIV-1-positive group and the HCV-positive/HIV-1-positive group treated with IL-1β-TNF-α were lower than the levels produced by DCs from the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative group at 48 h (P < 0.03) but not at 24 h (P was not significant). The levels of IL-12 p40 produced by DCs from all three virus-infected groups treated with IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ were lower than those produced by DCs from the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative group at 24 h and 48 h (P < 0.05). HCV(−), HCV negative; HIV-1(−), HIV-1 negative; HCV(+), HCV positive; HIV-1(+), HIV-1 positive.

The DCs produced larger amounts of the IL-12 p40 subunit than the IL-12 p70 subunit in all four groups of subjects after treatment with either IL-1β-TNF-α or IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ (Fig. 3B). There was an increase over time in the levels of IL-12 p40 production by DCs from all of the study groups that were treated with either IL-1β-TNF-α or IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ. Notably, the levels of IL-12 p40 produced by the DCs from the HCV-negative/HIV-1-positive and the HCV-positive/HIV-1-positive groups treated with IL-1β-TNF-α were lower than the levels produced by the DCs from the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative group at 48 h. Also, the levels of IL-12 p40 produced by DCs from all three virus-infected groups treated with IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ were lower than those produced by DCs from the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative group at 24 h and 48 h.

Taken together, these results indicate that chronic HCV infection, with or without HIV-1 infection, is associated with decreases in IL-12 p70 production by DCs in response to CD40L. This immunosuppressive effect of HCV infection was not directly associated with the production of the IL-12 p40 subunit and, more importantly, was reversed by addition of IFN-γ to the CD40L modulation regimen. The immunomodulation of DCs by the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α required addition of IFN-γ to induce IL-12 p70, regardless of the study group. In contrast to the results obtained by treatment with CD40L, there was no difference in the levels of IL-12 p70 produced by DCs treated with IL-1β-TNF-α-IFN-γ across the four study groups.

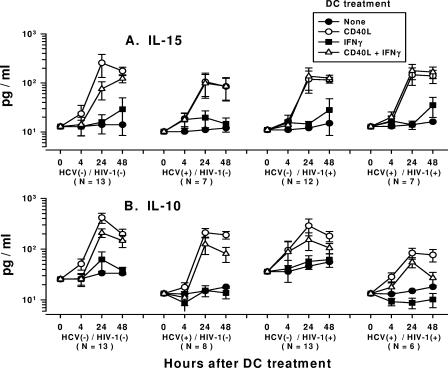

Production of IL-15 by DCs from HCV- and HIV-1-infected subjects.

We assessed the levels of IL-15, a T-cell-stimulating and survival factor, in the DCs treated with CD40L alone or CD40L-IFN-γ, the most potent stimulators of IL-12 production. Peak levels of IL-15 of approximately 100 to 250 pg/ml were induced by CD40L in the DC cultures by 24 h to 48 h (Fig. 4A). There were no significant differences in the levels of IL-15 production induced by CD40L-IFN-γ compared to those induced by CD40L alone in DCs from the four groups of study subjects, except that higher levels of IL-15 were produced at 24 h by CD40L-treated DCs derived from the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative group. The stimulation of DCs with IFN-γ alone produced very little IL-15 by 48 h (<30 pg/ml) (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Production of IL-15 (A) and IL-10 (B) by DCs from HCV- and HIV-1-infected subjects. The data are the mean ± standard error levels (pg/ml) of IL-15 or IL-10 production by DCs in response to the treatments shown. (A) Analysis within each group showed that DCs from all of the groups produced more IL-15 at 24 h and 48 h than at 0 h and that DCs treated with CD40L or CD40L-IFN-γ produced more IL-15 than untreated DCs at 24 h and 48 h (P < 0.05). Analysis across the four groups of study subjects showed that DCs treated with CD40L or CD40L-IFN-γ produced comparable levels of IL-15 at 24 and 48 h (P was not significant). (B) Analysis within each group showed that DCs from the four groups treated with CD40L or CD40L-IFN-γ produced more IL-10 at 24 h and 48 h than at 0 h (P < 0.05). DCs from the four groups treated with CD40L or CD40L-IFN-γ produced more IL-10 than untreated DCs did at 48 h (P < 0.05). Analysis across the four groups showed that there was a lower level of production of IL-10 by untreated DCs at 0 h for the two groups of HCV-infected subjects than for the uninfected or HIV-1-monoinfected groups, which remained lower through the 48 h (P < 0.05). Compared to the level of IL-10 production by DCs from the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative group that were treated with CD40L or CD40L-IFN-γ, the level of IL-10 production by DCs that were treated with CD40L or CD40L-IFN-γ was lower for the HCV-positive/HIV-1-positive group at 24 h and 48 h (P < 0.05). HCV(−), HCV negative; HIV-1(−), HIV-1 negative; HCV(+), HCV positive; HIV-1(+), HIV-1 positive.

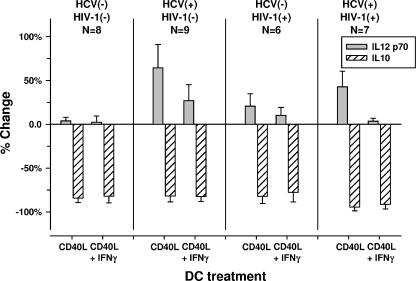

The decrease in IL-12 production by DCs during HCV infection is related to IL-10 activity.

We examined the DCs from the study subjects for associations of the defect in IL-12 production induced by CD40L alone with the production of IL-10, a known inhibitor of IL-12 production by DCs (48). The results for each group showed that very low levels of IL-10 were found in unstimulated DCs or DCs treated with IFN-γ alone (Fig. 4B). In a comparison across the groups, it was notable that there were lower basal (0-h) levels of production of IL-10 by untreated DCs in the two groups of HCV-infected subjects than in the uninfected or HIV-1-monoinfected groups, and the levels remained lower through the 48 h. Within each group, treatment of the DCs with CD40L induced larger amounts of IL-10 over time than treatment of DCs with CD40L-IFN-γ. The levels of IL-10 produced by DCs that were treated with CD40L or CD40L-IFN-γ were lower over time in the HCV-positive/HIV-1-positive group than in the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative group.

We next examined the effects on IL-12 p70 production by DCs that were treated with the anti-IL-10 MAb. Treatment with the anti-IL-10 MAb significantly neutralized most of the IL-10 in the DC cultures by 24 h (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5). This was associated with an increase in the amount of IL-12 p70 produced by CD40L-treated DCs from the two HCV-infected groups (Fig. 5). The results for the 48-h DC cultures were similar to the results for the 24-h DC cultures, with the same level of significance among the groups (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Increase in IL-12 p70 and decrease in IL-10 at 24 h by blocking with the anti-IL-10 MAb of DCs from HCV-positive/HIV-1-negative and HCV-positive/HIV-1-positive groups treated with CD40L. P was <0.05 for IL-12 p70 production by CD40L-treated DCs from the two HCV-positive groups compared to those from the HCV-negative/HIV-1-negative group. HCV(−), HCV negative; HIV-1(−), HIV-1 negative; HCV(+), HCV positive; HIV-1(+), HIV-1 positive.

Taken together, these results indicate that the capacity of DCs to produce IL-12 p70 in response to CD40L or CD40L-IFN-γ was not related to the levels of IL-10 produced by the DCs. However, the defect in IL-12 p70 production by DCs from HCV-infected subjects could be partially reversed by neutralizing IL-10 with the anti-IL-10 MAb. This suggests that the lower levels of production of IL-12 by these DCs is related in part to DC-derived IL-10.

Stimulation of CD4+ T-cell blastogenesis and IL-2 production by DCs from HCV-infected and HCV- and HIV-1-coinfected subjects.

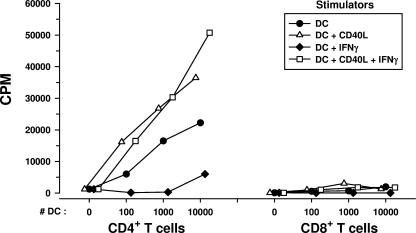

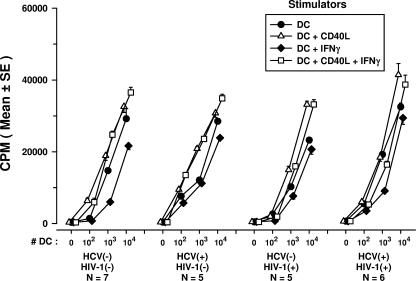

The ability of DCs to stimulate T-cell blastogenesis in an allogeneic MLR was studied as a function of their antigen-presenting capacity. Since both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells can respond to alloantigens (3, 41), we first compared purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from healthy donors in an MLR using allogeneic DCs from healthy donors. We confirmed that CD4+ T cells accounted for most of the MLR response (26) and that DCs treated with CD40L and IFN-γ induced higher levels of T-cell responses in the MLR (Fig. 6). Notably, we observed a decrease in the MLR reactivities of CD4+ T cells to DCs treated with IFN-γ alone. The DCs were then treated with the various immunomodulators and mixed with purified, allogeneic CD4+ T cells obtained from either of two healthy HCV- and HIV-1-negative donors. DCs derived from the three groups of HCV and/or HIV-1-infected persons and used in an immature state or matured with CD40L, with or without IFN-γ, stimulated normal levels of blastogenesis in allogeneic CD4+ T cells compared to the levels stimulated by uninfected donor DCs (Fig. 7). A decrease in the MLR induced by DCs treated with IFN-γ alone was evident among the four groups of study subjects.

FIG. 6.

MLR (mean cpm of triplicate cultures) of purified, allogeneic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in response to DCs that were treated with various immunomodulators.

FIG. 7.

Stimulation of blastogenesis of CD4+ T cells from healthy donors in an MLR by DCs from HCV-infected, HIV-1-infected, and HCV- and HIV-1-coinfected subjects that were treated in vitro with various immunomodulators. P was not significant for DCs treated with CD40L-IFN-γ and CD40L alone within each group and among the four groups of study subjects; for DCs treated with IFN-γ, P was <0.05 within each group of study subjects. HCV(−), HCV negative; HIV-1(−), HIV-1 negative; HCV(+), HCV positive; HIV-1(+), HIV-1 positive.

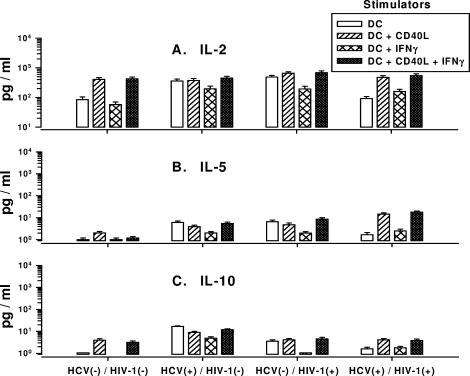

We next examined the MLR cultures for CD4+ Th1-cell reactivity, as determined by IL-2 production, and Th2-cell responses, as determined by IL-5 and IL-10 production. Unstimulated CD4+ T cells did not produce detectable IL-2 (data not shown). In contrast, high levels of IL-2 were detected in cultures of DCs mixed with CD4+ T cells, regardless of the HCV or HIV-1 infection status of the donors of the DCs (Fig. 8A). The larger amounts of IL-2 were induced by DCs treated with CD40L, with or without IFN-γ. Very low levels of IL-5 and IL-10 were produced in MLRs stimulated by DCs derived from all of the groups of subjects (Fig. 8B and C). DCs treated with IFN-γ alone produced the smallest amounts of these cytokines. There was no association between the levels of IL-2, IL-5, or IL-10 production and the MLRs induced by DCs from the various study groups (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

Production of IL-2 (A), IL-5 (B), and IL-10 (C) in MLR cultures of DCs from HCV- and HIV-1-infected subjects and purified CD4+ T cells from healthy donors. P was not significant for DCs treated with CD40L or CD40L-IFN-γ within each group and among the four groups of study subjects. HCV(−), HCV negative; HIV-1(−), HIV-1 negative; HCV(+), HCV positive; HIV-1(+), HIV-1 positive.

DISCUSSION

Chronic HCV infection can lead to severe liver disease that is enhanced by HIV-1 coinfection and that can persist during ART that suppresses the HIV-1 load (46). The T-cell immunity induced by DCs is considered to be important in the host control of HCV infection (17). Based on experimental data and clinical trials showing the efficacy of antigen-loaded monocyte-derived DCs in the treatment of HIV-1 infection (23) and certain cancers (2), the use of DC-based immunotherapy has been proposed for HCV infection (10, 15, 21). We therefore did the first comprehensive assessment of several key properties of monocyte-derived DCs in four groups of subjects with chronic HCV infection with and without HIV-1 coinfection, subjects with HIV-1 infection alone, and uninfected control subjects. We found that IL-12 p70 production in response to CD40L was decreased in DCs derived from subjects with chronic HCV infection compared to that in DCs from healthy uninfected subjects. Thus, monocyte-derived DCs have defects in IL-12 p70 production similar to those of circulating, myeloid DCs isolated directly from the blood of patients with chronic HCV infection (18). We demonstrated further that the defect in IL-12 p70 production was present in DCs derived from HCV-infected subjects with HIV-1 coinfection but not in DCs derived from HIV-1-monoinfected persons. Therefore, the decreases in p70 detected in our study were predominantly due to chronic HCV infection and not to an HIV-1 infection that was being suppressed by ART.

Notably, the lower levels of IL-12 p70 produced by the CD40L-treated DCs during HCV infection were not associated with a smaller amount of the IL-12 p40 subunit, except in the HCV-positive/HIV-1-positive group at 48 h. The inducible p40 portion of IL-12 is produced in excess quantities as a monomer, a homodimer, and a heterodimer complexed with IL-12 p35 to form the bioactive p70 form of IL-12 (48). Indeed, IL-12 p35 has been shown to be a subunit that limits the rate of IL-12 p70 production in monocytes (42), and analysis for its significance in HCV and HIV-1 infection is required.

We found that the defect in IL-12 p70 production could be eliminated by treatment of the DCs with IFN-γ together with CD40L. Exceptionally high levels of IL-12 p70 could be induced in DCs from the same subjects chronically infected with HCV by treatment with CD40L plus IFN-γ. Indeed, the levels of IL-12 p70 induced by this combination were extraordinarily high (40,000 to 50,000 pg/ml by 24 h) in DC cultures from all four groups of study subjects (uninfected controls and the three groups of infected subjects), consequently eliminating the differences in this DC function among them. This profound, multisignal effect of CD40L and IFN-γ on IL-12 production by DCs has previously been reported for healthy donors (12, 43). More recently, it has been shown that combinations of Toll-like receptor agonists can mature DCs and enhance their capacity to produce IL-12 (31).

The treatment of DCs with the proinflammatory activation factors IL-1β and TNF-α had little effect on IL-12 p70 production, regardless of the HCV or HIV-1 infection status. However, addition of IFN-γ to IL-1β and TNF-α resulted in the production of IL-12 p70 by the DCs, albeit at much lower levels than those induced by CD40L and IFN-γ. Interestingly, the level of production of IL-12 p70 by DCs from the three groups of HCV- and/or HIV-1-infected subjects that were treated with this triple combination of cytokines was not lower than the level of production by DCs from the uninfected subjects. We have recently examined other activation factors, including the cytokine IFN-α and the Toll-like receptor 3 ligand poly(I:C), together with TNF-α and IFN-γ. In accordance with our previously published data (25, 49), we observed that while these factors can prime DCs for elevated IL-12 p70 production upon subsequent triggering by CD40L, they cannot fully substitute for CD40L and IFN-γ in the induction of IL-12 production by DC (unpublished results).

The basis for the defect in IL-12 production by DCs derived from subjects chronically infected with HCV is unclear. We found no differences in the basic virologic parameters in the HCV- or HIV-1-monoinfected subjects compared to those in subjects with HCV and HIV-1 coinfection. That is, subjects chronically infected with HCV, with and without HIV-1 coinfection, had similar, high levels of HCV in their blood (1 × 106 to 2 × 106 RNA copies per ml of serum). Also, these subjects were infected with the predominant North American HCV genotypes, i.e., HCV genotypes 1a and 1b, with only 1 HCV-positive/HIV-1-negative subject infected with genotype 2 and none of the subjects infected with genotype 3. The two study groups infected with HIV-1 and receiving ART, with and without HCV infection, had similar, low levels of HIV-1 in their blood.

Because of the well-documented inhibitory effects of IL-10 on IL-12 production (7, 29, 48), we assessed DCs from the four groups of subjects for IL-10 activity as a basis for this IL-12 defect. We found that the levels of IL-10 produced in the untreated DC cultures were lower in the two HCV-infected groups than in the uninfected subjects. Furthermore, the only difference in IL-10 production for DCs that were treated with either CD40L or CD40L-IFN-γ was a lower level produced by DCs from the HCV- and HIV-1-coinfected group than by DCs from the uninfected subjects. This is in contrast to the association of high levels of IL-10 with small amounts of IL-12 p70 produced in myeloid DCs isolated directly from the blood of persons with chronic HCV infection (18). Of importance, however, is that we found that the neutralization of IL-10 with the anti-IL-10 MAb significantly increased the level of IL-12 production in CD40L-treated DCs from the HCV-monoinfected and HCV- and HIV-1-coinfected subjects. This effect was partial, as it did not normalize the levels of IL-12 like treatment of DCs with CD40L-IFN-γ did. Likewise, the lack of an effect of the anti-IL-10 MAb on the production of IL-12 by DCs treated with CD40L-IFN-γ is likely related to the maximal enhancement of IL-12 production by this immunomodulation. IL-10 has a variety of immunoregulatory properties, including the ability to decrease IL-12 and IL-18 production and inhibit DC differentiation and costimulation by DCs, which are primarily mediated through a STAT3 pathway (29). Interestingly, the anti-inflammatory properties of IL-10 have been exploited by the treatment of patients with chronic HCV infection with IL-10 to ameliorate hepatic fibrosis (27). However, such treatment with IL-10 has been linked to increases in the HCV load and decreases in HCV-specific T-cell function (32). There is also evidence that blockage of the IL-10 receptor in vitro can enhance T-cell reactivity in HCV infection (38). Clearly, although our data support a role for the IL-10 produced by DCs in the dysregulation of DC function during chronic HCV infection, further studies are needed to distinguish the function of IL-10 in HCV immunity and immunopathology.

DCs derived from blood monocytes of subjects with chronic HCV infection, with or without HIV-1 coinfection, were as capable as those from uninfected persons to express the surface molecules involved in the activation of T cells by DCs, i.e., MHC classes I and II and CD86, CD83, and CD209. This is comparable to the findings of other studies of chronic HCV infection that have not found defects in the expression of coreceptors or activation molecules in monocyte-derived DCs (22, 35). Our data extend this finding to persons with HCV and HIV-1 coinfection and confirm previous results from our laboratory and others on the normal expression of these markers on DCs from HIV-1-infected persons receiving virus-suppressive ART (6, 13, 33).

We observed that DCs from the three infected groups stimulated MLR responses in purified, allogeneic CD4+ T cells comparably to DCs derived from healthy donors. This confirms and expands the findings of other reports on the normal stimulation of an allogeneic MLR by monocyte-derived DCs from either HCV-monoinfected or HCV- and HIV-1-coinfected persons (22, 35, 44). In our study, DCs that had been matured with CD40L and IFN-γ induced the largest amounts of IL-2 in the MLR compared to the amounts induced by immature DCs not treated with either molecule or DCs treated only with IFN-γ. No differences in the levels of production of IL-2, IL-5, and IL-10 in the MLR cultures were found among the infected and uninfected subjects. Expression of the HCV core and E1 antigens in the DCs from healthy donors can inhibit the priming of naïve CD4+ T cells (39). However, we did not find HCV RNA in the monocyte-derived DCs from our study subjects with chronic HCV infection. Finally, we noted that DCs treated with IFN-γ alone induced lower levels of MLR reactivity than immature DCs in all four groups of subjects. This could be related to the previously reported induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by IFN-γ in DCs, which results in the inhibition of T-cell stimulation by the DCs (14).

This study indicates that DCs derived from persons with chronic HCV infection, with or without HIV-1 coinfection, retain the ability to respond to the combination of CD40L and IFN-γ, resulting in the normalization of their production of IL-12. This multisignal approach could allow DCs to be engineered to induce T cells to target HCV infection in the host as a potent form of immunotherapy. This is based on the work of our group (N. C. Connolly, T. L. Whiteside, C. C. Wilson, T. V. Kondragunta, C. R. Rinaldo, and S. A. Riddler, submitted for publication) and others (9, 24) on similar models of immunotherapy for HIV-1 infection, which has many virologic and immunologic properties similar to those of persistent HCV infection. Our goal of the ex vivo engineering of DCs for use in immunotherapy of HCV and HIV-1 infections is to enhance their ability to modulate virus-specific T-cell immunity after in vivo infusion. This is based on a three-signal model in which activated, mature DCs present the MHC-peptide complex to the T-cell receptor (signal 1), as well as a costimulatory signal (e.g., CD86-CD28) (signal 2), to induce antigen-specific T-cell reactivity. These DCs provide a third signal (signal 3), particularly IL-12, to elicit either CD4+ Th1- or Th2-cell function (25). IFN-γ is the key molecule that induces IL-12 production by the DCs, which in turn polarizes Th1 cells to produce of IFN-γ and other enhancers of antiviral CD8+ T-cell reactivity. Thus, a distinction may need to be made between the activation of DCs from HCV- and HIV-1-infected persons to produce large amounts of IL-12 ex vivo and more limited, ex vivo priming of DCs to enhance their capacity to produce high levels of IL-12 after in vivo infusion. To achieve the latter effect, which could be more relevant to the clinical outcome of immunotherapy, we are currently examining the ex vivo treatment of DCs with IFN-γ and other activators, such as Toll-like receptor agonists, to prime DCs for IL-12 production and stimulation of anti-HCV CD8+ T-cell reactivity upon subsequent interaction with CD40L- and IFN-γ-expressing Th1 cells.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Pitt Men's Study participants for their blood donations. We thank Amgen (Seattle, WA) for the gift of CD40L (MTA no. 200312724) and K. Phalmer (Amgen) for assistance; W. Buchanan for clinical assistance; D. Vy, L. Borowski, C. Kalinyak, P. Zhang, W. Jiang, N. Krisnamoorthy, S. McQuiston, H. Richards, and L. Zheng for technical assistance; A. Brickner for helpful comments; and C. Perfetti for database assistance.

This work was supported by NIH grants R37-AI41870, U01-AI35041, and P01-AI055794.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anthony, D. D., N. L. Yonkers, A. B. Post, R. Asaad, F. P. Heinzel, M. M. Lederman, P. V. Lehmann, and H. Valdez. 2004. Selective impairments in dendritic cell-associated function distinguish hepatitis C virus and HIV infection. J. Immunol. 1724907-4916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banchereau, J., and A. K. Palucka. 2005. Dendritic cells as therapeutic vaccines against cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5296-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barber, L. D., and J. A. Madrigal. 2006. Exploiting beneficial alloreactive T cells. Vox Sang. 9120-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowen, D. G., and C. M. Walker. 2005. Adaptive immune responses in acute and chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Nature 436946-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caliendo, A. M., A. Valsamakis, Y. Zhou, B. Yen-Lieberman, J. Andersen, S. Young, A. Ferreira-Gonzalez, G. J. Tsongalis, R. Pyles, J. W. Bremer, and N. S. Lurain. 2006. Multilaboratory comparison of hepatitis C virus viral load assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 441726-1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chougnet, C., S. S. Cohen, T. Kawamura, A. L. Landay, H. A. Kessler, E. Thomas, A. Blauvelt, and G. M. Shearer. 1999. Normal immune function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells from HIV-infected individuals: implications for immunotherapy. J. Immunol. 1631666-1673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Jong, E. C., H. H. Smits, and M. L. Kapsenberg. 2005. Dendritic cell-mediated T cell polarization. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 26289-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Encke, J., J. Findeklee, J. Geib, E. Pfaff, and W. Stremmel. 2005. Prophylactic and therapeutic vaccination with dendritic cells against hepatitis C virus infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 142362-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia, F., M. Lejeune, N. Climent, C. Gil, J. Alcami, V. Morente, L. Alos, A. Ruiz, J. Setoain, E. Fumero, P. Castro, A. Lopez, A. Cruceta, C. Piera, E. Florence, A. Pereira, A. Libois, N. Gonzalez, M. Guila, M. Caballero, F. Lomena, J. Joseph, J. M. Miro, T. Pumarola, M. Plana, J. M. Gatell, and T. Gallart. 2005. Therapeutic immunization with dendritic cells loaded with heat-inactivated autologous HIV-1 in patients with chronic HIV-1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 1911680-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gowans, E. J., K. L. Jones, M. Bharadwaj, and D. C. Jackson. 2004. Prospects for dendritic cell vaccination in persistent infection with hepatitis C virus. J. Clin. Virol. 30283-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greub, G., B. Ledergerber, M. Battegay, P. Grob, L. Perrin, H. Furrer, P. Burgisser, P. Erb, K. Boggian, J. C. Piffaretti, B. Hirschel, P. Janin, P. Francioli, M. Flepp, and A. Telenti. 2000. Clinical progression, survival, and immune recovery during antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus coinfection: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Lancet 3561800-1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilkens, C. M., P. Kalinski, M. de Boer, and M. L. Kapsenberg. 1997. Human dendritic cells require exogenous interleukin-12-inducing factors to direct the development of naive T-helper cells toward the Th1 phenotype. Blood 901920-1926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang, X. L., Z. Fan, B. A. Colleton, R. Buchli, H. Li, W. H. Hildebrand, and C. R. Rinaldo, Jr. 2005. Processing and presentation of exogenous HLA class I peptides by dendritic cells from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected persons. J. Virol. 793052-3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwu, P., M. X. Du, R. Lapointe, M. Do, M. W. Taylor, and H. A. Young. 2000. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase production by human dendritic cells results in the inhibition of T cell proliferation. J. Immunol. 1643596-3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakimi, K. 2003. Immune-based novel therapies for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hum. Cell 16191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalinski, P., J. H. Schuitemaker, C. M. Hilkens, E. A. Wierenga, and M. L. Kapsenberg. 1999. Final maturation of dendritic cells is associated with impaired responsiveness to IFN-gamma and to bacterial IL-12 inducers: decreased ability of mature dendritic cells to produce IL-12 during the interaction with Th cells. J. Immunol. 1623231-3236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanto, T., and N. Hayashi. 2006. Immunopathogenesis of hepatitis C virus infection: multifaceted strategies subverting innate and adaptive immunity. Intern. Med. 45183-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanto, T., M. Inoue, H. Miyatake, A. Sato, M. Sakakibara, T. Yakushijin, C. Oki, I. Itose, N. Hiramatsu, T. Takehara, A. Kasahara, and N. Hayashi. 2004. Reduced numbers and impaired ability of myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells to polarize T helper cells in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 1901919-1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuzushita, N., S. H. Gregory, N. A. Monti, R. Carlson, S. Gehring, and J. R. Wands. 2006. Vaccination with protein-transduced dendritic cells elicits a sustained response to hepatitis C viral antigens. Gastroenterology 130453-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langenkamp, A., M. Messi, A. Lanzavecchia, and F. Sallusto. 2000. Kinetics of dendritic cell activation: impact on priming of TH1, TH2 and nonpolarized T cells. Nat. Immunol. 1311-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson, M. 2006. The dendritic cell: the immune system's adjuvant—a strategy to develop a HCV vaccine? Gastroenterology 130603-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longman, R. S., A. H. Talal, I. M. Jacobson, M. L. Albert, and C. M. Rice. 2004. Presence of functional dendritic cells in patients chronically infected with hepatitis C virus. Blood 1031026-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lori, F., L. M. Kelly, and J. Lisziewicz. 2004. APC-targeted immunization for the treatment of HIV-1. Expert Rev. Vaccines 3S189-S198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu, W., L. C. Arraes, W. T. Ferreira, and J. M. Andrieu. 2004. Therapeutic dendritic-cell vaccine for chronic HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 101359-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mailliard, R. B., A. Wankowicz-Kalinska, Q. Cai, A. Wesa, C. M. Hilkens, M. L. Kapsenberg, J. M. Kirkwood, W. J. Storkus, and P. Kalinski. 2004. Alpha-type-1 polarized dendritic cells: a novel immunization tool with optimized CTL-inducing activity. Cancer Res. 645934-5937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martins, S. L., L. S. St John, R. E. Champlin, E. D. Wieder, J. McMannis, J. J. Molldrem, and K. V. Komanduri. 2004. Functional assessment and specific depletion of alloreactive human T cells using flow cytometry. Blood 1043429-3436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McHutchison, J. G., G. Giannelli, L. Nyberg, L. M. Blatt, K. Waite, P. Mischkot, S. Pianko, A. Conrad, and P. Grint. 1999. A pilot study of daily subcutaneous interleukin-10 in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 191265-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McIlroy, D., and M. Gregoire. 2003. Optimizing dendritic cell-based anticancer immunotherapy: maturation state does have clinical impact. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 52583-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mege, J. L., S. Meghari, A. Honstettre, C. Capo, and D. Raoult. 2006. The two faces of interleukin 10 in human infectious diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6557-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murakami, H., S. M. Akbar, H. Matsui, N. Horiike, and M. Onji. 2004. Decreased interferon-alpha production and impaired T helper 1 polarization by dendritic cells from patients with chronic hepatitis C. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 137559-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Napolitani, G., A. Rinaldi, F. Bertoni, F. Sallusto, and A. Lanzavecchia. 2005. Selected Toll-like receptor agonist combinations synergistically trigger a T helper type 1-polarizing program in dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 6769-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson, D. R., Z. Tu, C. Soldevila-Pico, M. Abdelmalek, H. Zhu, Y. L. Xu, R. Cabrera, C. Liu, and G. L. Davis. 2003. Long-term interleukin 10 therapy in chronic hepatitis C patients has a proviral and anti-inflammatory effect. Hepatology 38859-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newton, P. J., I. V. Weller, I. G. Williams, R. F. Miller, A. Copas, R. S. Tedder, D. R. Katz, and B. M. Chain. 2006. Monocyte derived dendritic cells from HIV-1 infected individuals partially reconstitute CD4 T-cell responses. AIDS 20171-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Sullivan, B., and R. Thomas. 2003. CD40 and dendritic cell function. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2383-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piccioli, D., S. Tavarini, S. Nuti, P. Colombatto, M. Brunetto, F. Bonino, P. Ciccorossi, F. Zorat, G. Pozzato, C. Comar, S. Abrignani, and A. Wack. 2005. Comparable functions of plasmacytoid and monocyte-derived dendritic cells in chronic hepatitis C patients and healthy donors. J. Hepatol. 4261-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pulendran, B. 2006. Division of labor and cooperation between dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 7699-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rehermann, B., and M. Nascimbeni. 2005. Immunology of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5215-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rigopoulou, E. I., W. G. Abbott, P. Haigh, and N. V. Naoumov. 2005. Blocking of interleukin-10 receptor—a novel approach to stimulate T-helper cell type 1 responses to hepatitis C virus. Clin. Immunol. 11757-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarobe, P., J. J. Lasarte, N. Casares, A. Lopez-Diaz de Cerio, E. Baixeras, P. Labarga, N. Garcia, F. Borras-Cuesta, and J. Prieto. 2002. Abnormal priming of CD4+ T cells by dendritic cells expressing hepatitis C virus core and E1 proteins. J. Virol. 765062-5070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39a.Schiller, M., M. Metze, T. A. Lugar, S. Grabbe, and M. Gunzer. 2006. Immune response modifiers—mode of action. Exp. Dermatol. 15331-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shepard, C. W., L. Finelli, and M. J. Alter. 2005. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5558-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherman, L. A., and S. Chattopadhyay. 1993. The molecular basis of allorecognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 11385-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snijders, A., C. M. Hilkens, T. C. van der Pouw Kraan, M. Engel, L. A. Aarden, and M. L. Kapsenberg. 1996. Regulation of bioactive IL-12 production in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytes is determined by the expression of the p35 subunit. J. Immunol. 1561207-1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Snijders, A., P. Kalinski, C. M. Hilkens, and M. L. Kapsenberg. 1998. High-level IL-12 production by human dendritic cells requires two signals. Int. Immunol. 101593-1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stebbing, J., S. Patterson, S. Portsmouth, C. Thomas, R. Glassman, A. Wildfire, F. Gotch, M. Bower, M. Nelson, and B. Gazzard. 2004. Studies on the allostimulatory function of dendritic cells from HCV-HIV-1 co-infected patients. Cell Res. 14251-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steinman, R. M. 2003. Some interfaces of dendritic cell biology. APMIS 111675-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan, Y. J., S. G. Lim, and W. Hong. 2006. Understanding human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and hepatitis C virus coinfection. Curr. HIV Res. 421-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reference deleted.

- 48.Trinchieri, G. 2003. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3133-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vieira, P. L., E. C. de Jong, E. A. Wierenga, M. L. Kapsenberg, and P. Kalinski. 2000. Development of Th1-inducing capacity in myeloid dendritic cells requires environmental instruction. J. Immunol. 1644507-4512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang, Q. C., Z. H. Feng, Y. X. Zhou, and Q. H. Nie. 2005. Induction of hepatitis C virus-specific cytotoxic T and B cell responses by dendritic cells expressing a modified antigen targeting receptor. World J. Gastroenterol. 11557-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wertheimer, A. M., A. Bakke, and H. R. Rosen. 2004. Direct enumeration and functional assessment of circulating dendritic cells in patients with liver disease. Hepatology 40335-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiang, M., C. Eisenbach, C. M. Lupu, E. Ernst, W. Stremmel, and J. Encke. 2006. Induction of antigen-specific immune responses in vivo after vaccination with dendritic cells transduced with adenoviral vectors encoding hepatitis C virus NS3. Viral Immunol. 19210-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu, H., H. Huang, J. Xiang, L. A. Babiuk, and S. van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk. 2006. Dendritic cells pulsed with hepatitis C virus NS3 protein induce immune responses and protection from infection with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing NS3. J. Gen. Virol. 871-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]