Abstract

Neonatal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 12 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and 84 uninfected children were assessed for their distribution of T-cell receptors (TCRs) by flow cytometry employing monoclonal antibodies to 14 Vβ types. Vβ 2, 5c, and 13 were the most commonly found on CD4 cells (in that order). There was a bimodal distribution of Vβ 2, being most common in 48% of individuals but in limiting frequency (<2% of CD4) in 21%. Vβ 2, 3, 8b, and 13 were most commonly expressed on CD8 cells at similar frequencies. There was little difference in the pattern displayed among the infected compared to that of the uninfected. The variation of the distribution over time was studied in 12 infants (7 infected). Only a single HIV-infected child had a significant difference in the interquartile range; none of the HIV-negative patients showed a significant difference. In conclusion, newborns demonstrate different distributions of TCR Vβ types on CD4 and CD8 cells. HIV infection produces no change in neonatal TCR and little change over the course of 2 years compared to that seen in the uninfected.

Peripheral blood lymphocytes emerge from the thymus after a process of negative selection. After antigenic exposure, both positive selection and negative selection may occur, modifying the “naïve” repertoire. van den Beemd et al. noted similar Vβ usage among 36 healthy controls (ranging from 5 neonates to adults as old as 86 years) in CD4 and CD8 T cells for most tested Vβ domains except for Vβ 2, 5.1, 6.7, 9.1, and 22 (higher in CD4+) as well as Vβ 1, 7.1, 14, and 23 (higher in CD8) (24). In the small subgroup of neonates, there appeared to be similar frequencies in the CD4 and CD8 populations. Their study confirmed observations by Grunewald et al., who noted skewing in the distribution of Vβ 5.1, 6.7, 8, and 12, with overrepresentation of these domains in CD4 T cells (7). Except for these five neonates, there is little information about the distribution of T-cell receptor (TCR) markers in newborns, which are presumably affected only by negative selection. Moreover, there is no information about the variation in this repertoire once antigenic exposure is in place. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection has antigen-driven, direct cell killing and possibly superantigenic effects on T cells and might result in predictable TCR signatures on HIV-infected patients. We undertook a prospective evaluation of the TCR repertoire by performing Vβ typing using flow cytometry to detect a number of markers detected by commercially available monoclonal antibodies by typing HIV-exposed but uninfected and infected children. For comparison, we also studied a small number of cord blood specimens of HIV-uninfected mothers. We also performed a longitudinal analysis of a group of HIV-infected children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

HIV-infected pregnant women were enrolled in an institutional review board-approved study that evaluated the potential effect of perinatal HIV infection on the development of infant T-cell receptors. The initial analysis occurred within 72 h of birth and was either performed on cord blood or on peripheral blood. Blood was subsequently obtained every 3 months (range, 2 to 4 months) for as long as the parent allowed. HIV infection was determined by HIV culture or PCR performed on peripheral blood at birth, 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks. A diagnosis of HIV infection required two separate positive assays. Avoidance of HIV infection was confirmed by the loss of antibody to HIV by 15 months of age. An additional six cord blood samples from HIV-uninfected pregnancies were also obtained for typing.

TCR typing.

Whole blood was incubated with a series of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled monoclonal antibodies directed at the variable region of the β chain of different TCRs. Proper gating by flow cytometry was achieved using control mouse immunoglobulin G1 antibodies labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate, phycoerythrin, and phycocyanin, as well as phycocyanin-labeled anti-CD4 and phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD8 antibodies. The monoclonal antibodies were purchased from different vendors (initially from T Cell Diagnostics [Woburn, MA], Immunotech [Miami, FL], and Endogen [Woburn, MA]; most recently, all from Becton Dickinson Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ), maintaining the original clones, as the products were available. These represent about half of the total TCR repertoire. Both two- and three-color flow analyses were performed using a FACScan cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analyses.

The frequencies of 14 Vβ TCRs were assessed and compared between neonatal CD4 and CD8 T cells from 84 HIV-uninfected and 12 HIV-infected individuals at birth (baseline) using numerical and graphical summary statistics. The longitudinal variation in the frequencies over time was assessed in seven HIV-infected and five uninfected children to determine the possible effects of chronic HIV exposure on the T-cell repertoire. Nonparametric methods were used in all statistical analyses because Vβ receptor frequencies were not normally distributed.

Baseline data were analyzed as follows. For each Vβ receptor, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to compare the Vβ receptor frequencies between the CD4 T cells and the CD8 T cells, separately for the HIV-infected and the uninfected patients. The Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare the Vβ receptor frequencies between the HIV-infected and uninfected patients for the CD4 and CD8 T cells separately. Spearman's correlation coefficients were used to describe associations between CD4 and CD8 TCR frequencies.

For longitudinal data, the following tests were performed: Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare the variability of each Vβ receptor over time between the HIV-infected and uninfected patients; the tests were conducted separately for CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells. The interquartile range (IQR) of each Vβ receptor frequency over time was used as a measure of variability. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the median IQR over all Vβ receptor frequencies in CD4 T cells with the median IQR in the CD8 T cells, separately for each patient.

Each of the tests described above involved multiple comparisons. To account for multiple comparisons, the P values from each series of tests were adjusted according to the Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate method and the adjusted P values were reported (1). Adjusted P values of 5% or less were considered significant. Confidence intervals for each β receptor for CD4 and CD8 cells and for the pairwise differences between CD4 and CD8 cells were calculated using bootstrap methods for HIV-positive and -negative subjects.

The analyses were performed using R (19) (and Bioconductor, open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics [www.bioconductor.org]).

RESULTS

Baseline analyses.

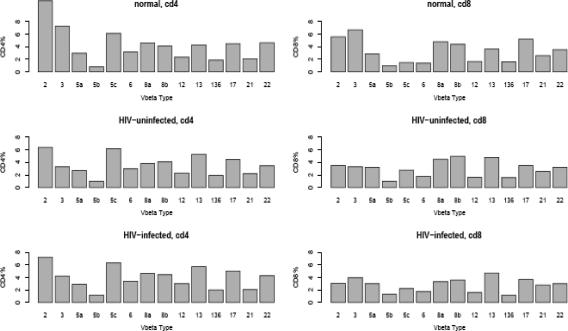

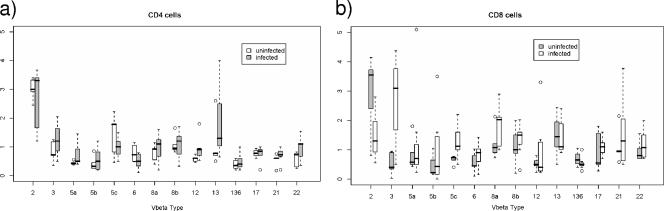

Ninety-six newborns were studied. The racial distribution was 46% African American, 41% Hispanic, and 11% Caucasian. Fifty-one percent were female. Eighty-four of the children proved to be uninfected. In 5 of the 12 HIV-infected children, the virus was detected at birth, and these children were considered infected in utero. All children were infected with a virus that did not utilize the CXCR4 receptor, as determined by MT-2 cell tropism. The Vβ receptor frequencies of CD4 and CD8 T cells among the HIV-infected, HIV-exposed but uninfected children, and children born of HIV-uninfected mothers (“normal”) are shown in Fig. 1. There are substantial similarities in Vβ frequencies for HIV-positive and -negative subjects, in both the CD4 T cells and the CD8 T cells (not statistically significant).

FIG. 1.

Median frequencies of Vβ receptors for CD4 T cells (left panels) and CD8 T cells (right panels) for HIV-negative (n = 84), HIV-positive subjects (n = 12), and cord blood samples from healthy (“normal”) mothers (n = 6). The unlabeled bars correspond to Vβ 13.6.

CD4 TCR distribution.

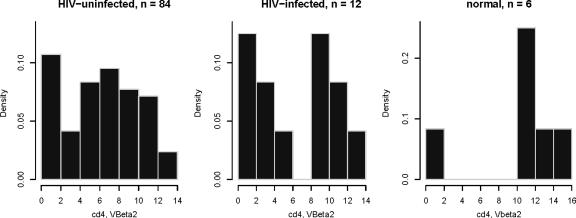

Seventy-three (87%) of 84 HIV-exposed but uninfected children had Vβ 2, 5c, or 13 as the most prevalent of their neonatal TCRs. Vβ 5c was the most prevalent in 21 children (25%), and Vβ 13 was the most prevalent in 12 children (14%). There was a bimodal distribution of Vβ 2 on CD4 T cells, with it being the most frequent TCR gene in 40 children (48%) while 18 (21%) had a very low (<2%) frequency of Vβ 2 (Fig. 2). There appeared to be some “linkage” of receptor distribution, as 20 of the 40 with Vβ 2 as the most prevalent TCR had Vβ 5c as the next most prevalent. However, those with Vβ 5c as the most prevalent were more likely to have Vβ 13 as the next most prevalent (10/21) than Vβ 2 (2/21). Eight of the individuals with Vβ 5c as the most prevalent had Vβ 2 percentages of <2%. The distribution of TCRs on CD4 T cells among the 12 HIV-infected neonates was not dissimilar to those of the HIV-exposed but uninfected neonates. Six had Vβ 2 as their most prevalent TCR, and three had Vβ 5c as their most prevalent TCR.

FIG. 2.

Histograms of Vβ 2 frequencies in CD4 cells from HIV-uninfected, HIV-infected, and healthy individuals. Vβ 2 frequencies are expressed as density. The CD4 cells from HIV-uninfected, HIV-infected, and cord blood specimens from healthy (“normal”) HIV-uninfected mothers. The y axis represents the proportion of cells that demonstrate the TCR type represented on the x axis. The histograms suggest that the distribution of Vβ 2 may be bimodal.

CD8 TCR distribution.

Seventy-seven (92%) of the 84 HIV-uninfected children had Vβ 2 (17%), 3 (19%), 8a (11%), 8b (19%), 13 (19%), and 17 (7%) as the most prevalent neonatal TCRs. As there was no difference in TCRs in those five who were infected in utero and the seven infected perinatally, the results were merged. The Vβ distribution among the infected cohort of 12 neonates was not very different, with Vβ 2 most prevalent in 3 (25%), Vβ 3 in 3 (25%), and Vβ 8a in 2 (17%).

Comparison of CD4 and CD8 frequencies.

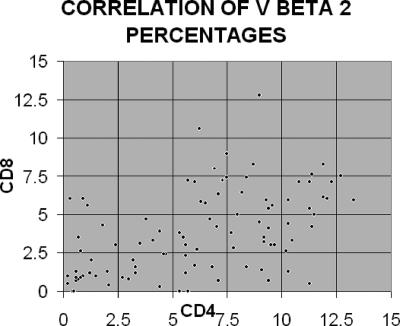

The frequencies of Vβ 2 expressed by CD4 and CD8 cells are shown in Fig. 3. Table 1 presents the results of pairwise comparisons of baseline Vβ frequencies from neonatal individuals between CD4 cells and CD8 cells. Tests were run separately for HIV-infected and HIV-exposed but uninfected patients. Note that for the HIV-negative patients, there are significant differences between CD4 and CD8 cells for 10 out of the 14 Vβ cell types, but for HIV-uninfected patients, there are no significant results. By examining the differences in median values of the CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells for the HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups, we can surmise that much of this difference in significance of results for the two groups is due to sample size.

FIG. 3.

Display of Vβ 2 expressed by CD4 and CD8 T cells. Each point represents a single individual.

TABLE 1.

Pairwise comparisons of Vβ frequencies on CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells by HIV status

| Patient group and TCR | Median frequency of TCR (95% CIa) on:

|

Adj. P value for diff.b | 95% CI for diff.c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 T cells | CD8 T cells | |||

| HIV infected (n = 12) | ||||

| Vβ 2 | 7.2 (2.7, 9.9) | 3.1 (1.1, 7.1) | 0.087 | 0.1, 5.5 |

| Vβ 3 | 4.2 (2.1, 6.3) | 4.0 (0.8, 6.9) | 0.973 | −1.0, 1.1 |

| Vβ 5a | 2.9 (2.0, 3.4) | 3.0 (2.4, 4.1) | 0.543 | −1.3, 0.7 |

| Vβ 5b | 1.2 (0.8, 1.4) | 1.3 (0.9, 2.4) | 0.298 | −1.1, 0.4 |

| Vβ 5c | 6.3 (6.1, 6.8) | 2.2 (2.0, 3.7) | 0.056 | 2.4, 5.2 |

| Vβ 6 | 3.4 (1.3, 3.8) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.2) | 0.087 | 0.0, 2.2 |

| Vβ 8a | 4.6 (3.9, 6.0) | 3.3 (2.4, 5.9) | 0.117 | 0.6, 1.5 |

| Vβ 8b | 4.4 (3.8, 5.3) | 3.6 (2.9, 5.0) | 0.453 | −0.6, 2.2 |

| Vβ 12 | 3.0 (1.7, 3.8) | 1.6 (0.6, 3.3) | 0.316 | −0.4, 2.8 |

| Vβ 13 | 5.7 (3.8, 6.0) | 4.7 (2.1, 5.2) | 0.118 | 0.0, 2.0 |

| Vβ 13.6 | 2.0 (1.8, 2.5) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.5) | 0.087 | 0.3, 1.5 |

| Vβ 17 | 5.0 (4.4, 5.3) | 3.7 (3.1, 4.9) | 0.277 | 0.4, 2.1 |

| Vβ 21 | 2.1 (1.5, 3.2) | 2.8 (1.4, 3.1) | 0.298 | −1.1, 0.6 |

| Vβ 22 | 4.3 (3.5, 5.5) | 3.0 (2.6, 3.5) | 0.087 | 0.4, 2.5 |

| HIV uninfected (n = 84) | ||||

| Vβ 2 | 6.4 (5.6, 7.5) | 3.5 (2.7, 4.4) | 0.001 | 1.5, 3.8 |

| Vβ 3 | 3.3 (2.9, 4.0) | 3.3 (2.4, 3.9) | 0.273 | −0.4, 0.2 |

| Vβ 5a | 2.7 (2.6, 2.8) | 3.2 (2.8, 3.3) | 0.062 | −0.5, 0.0 |

| Vβ 5b | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 0.260 | 0.0, 0.2 |

| Vβ 5c | 6.2 (5.5, 6.5) | 2.8 (2.5, 3.2) | 0.0001 | 2.7, 3.5 |

| Vβ 6 | 3.0 (2.6, 3.5) | 1.8 (1.5, 2.0) | 0.0001 | 0.5, 1.5 |

| Vβ 8a | 3.8 (3.7, 4.3) | 4.5 (4.1, 4.8) | 0.0002 | −0.8, −0.2 |

| Vβ 8b | 4.1 (3.9, 4.3) | 5.0 (4.6, 5.3) | 0.0001 | −1.2, −0.4 |

| Vβ 12 | 2.3 (2.1, 2.5) | 1.6 (1.4, 1.8) | 0.0001 | 0.4, 0.9 |

| Vβ 13 | 5.3 (5.1, 5.6) | 4.8 (4.3, 5.1) | 0.021 | 0.2, 0.8 |

| Vβ 13.6 | 1.9 (1.7, 2.0) | 1.6 (1.4, 1.8) | 0.008 | 0.1, 0.5 |

| Vβ 17 | 4.5 (4.2, 4.8) | 3.5 (3.3, 4.0) | 0.002 | 0.3, 0.9 |

| Vβ 21 | 2.2 (2.1, 2.4) | 2.6 (2.3, 2.8) | 0.007 | −0.6, −0.2 |

| Vβ 22 | 3.5 (3.2, 3.8) | 3.2 (3.0, 3.6) | 0.248 | −0.1, 0.5 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Adj. P value for diff., adjusted P value for difference between the median values for CD4 and CD8 cells. The adjusted values that were not statistically significant are shown in boldface type.

95% CI for diff., 95% CI for difference between the median values for CD4 and CD8 cells.

Comparison of Vβ frequencies of HIV-infected and -uninfected individuals.

Table 2 presents the results of comparisons of baseline Vβ frequencies from HIV-infected (n = 12) and HIV-uninfected neonatal individuals (n = 84). Tests were run separately for CD4 and CD8 T cells. None of the differences were statistically significant after multiple comparison adjustment as was noted above (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Comparisons of Vβ frequencies on CD4 and CD8 of HIV-infected and -uninfected individuals

| T-cell type and TCR | Median frequency of TCR (95% CIa) in:

|

Unadjusted P value for diff.b | Adjusted P value for diff.b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-uninfected patients (n = 84) | HIV-infected patients (n = 12) | |||

| CD4 | ||||

| Vβ 2 | 6.40 (5.55, 7.50) | 7.20 (2.65, 9.85) | 0.69 | 0.96 |

| Vβ 3 | 3.30 (2.90, 3.95) | 4.20 (2.05, 6.30) | 0.36 | 0.82 |

| Vβ 5a | 2.70 (2.65, 2.81) | 2.90 (2.10, 3.40) | 0.77 | 0.96 |

| Vβ 5b | 1.00 (1.00, 1.10) | 1.20 (0.80, 1.40) | 0.64 | 0.96 |

| Vβ 5c | 6.20 (5.45, 6.50) | 6.30 (6.10, 6.80) | 0.47 | 0.82 |

| Vβ 6 | 3.00 (2.60, 3.50) | 3.40 (1.25, 3.80) | 0.92 | 0.96 |

| Vβ 8a | 3.80 (3.70, 4.30) | 4.60 (3.90, 6.10) | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| Vβ 8b | 4.10 (3.85, 4.30) | 4.40 (3.75, 5.30) | 0.28 | 0.82 |

| Vβ 12 | 2.30 (2.10, 2.50) | 3.00 (1.65, 3.80) | 0.33 | 0.82 |

| Vβ 13 | 5.30 (5.10, 5.60) | 5.70 (3.50, 5.90) | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Vβ 13.6 | 1.90 (1.70, 2.00) | 2.00 (1.75, 2.50) | 0.19 | 0.82 |

| Vβ 17 | 4.45 (4.15, 4.80) | 5.00 (4.40, 5.25) | 0.41 | 0.82 |

| Vβ 21 | 2.20 (2.10, 2.40) | 2.05 (1.45, 3.20) | 0.82 | 0.96 |

| Vβ 22 | 3.45 (3.20, 3.80) | 4.25 (3.45, 5.50) | 0.04 | 0.25 |

| CD8 | ||||

| Vβ 2 | 3.50 (2.65, 4.35) | 3.05 (1.10, 7.10) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Vβ 3 | 3.30 (2.40, 3.90) | 3.95 (0.75, 6.90) | 0.93 | 1.00 |

| Vβ 5a | 3.20 (2.87, 3.23) | 3.00 (2.40, 4.10) | 0.70 | 1.00 |

| Vβ 5b | 1.00 (0.90, 1.10) | 1.30 (0.90, 2.40) | 0.13 | 0.59 |

| Vβ 5c | 2.80 (2.50, 3.10) | 2.20 (1.95, 3.70) | 0.54 | 1.00 |

| Vβ 6 | 1.75 (1.50, 2.00) | 1.75 (1.30, 2.15) | 0.91 | 1.00 |

| Vβ 8a | 4.50 (4.10, 4.80) | 3.30 (2.75, 5.90) | 0.47 | 1.00 |

| Vβ 8b | 5.00 (4.60, 5.25) | 3.60 (2.85, 4.95) | 0.04 | 0.59 |

| Vβ 12 | 1.60 (1.40, 1.80) | 1.60 (0.70, 3.40) | 0.98 | 1.00 |

| Vβ 13 | 4.80 (4.30, 5.10) | 4.70 (2.15, 5.15) | 0.27 | 0.95 |

| Vβ 13.6 | 1.55 (1.35, 1.80) | 1.15 (1.00, 1.50) | 0.11 | 0.59 |

| Vβ 17 | 3.50 (3.30, 4.00) | 3.65 (3.05, 4.85) | 0.95 | 1.00 |

| Vβ 21 | 2.55 (2.30, 2.80) | 2.80 (1.35, 3.05) | 0.90 | 1.00 |

| Vβ 22 | 3.20 (3.00, 3.55) | 3.00 (2.60, 3.45) | 0.45 | 1.00 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Unadjusted and adjusted P values for the differences between the median values for HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected patients.

Correlation of Vβ frequencies among CD4 and CD8 populations.

Given in Table 3 are Spearman's coefficients of correlation between the CD4 and CD8 T cells for each Vβ receptor frequency and the corresponding P values adjusted for multiple comparison. Most of the frequencies are highly correlated. It should be noted, however, that there are a number of individuals with low (i.e., <2%) Vβ 2 on their CD4 T cells who maintain higher frequencies of this receptor on their CD8 T cells, implying the absence of a generalized depletion of Vβ 2.

TABLE 3.

Spearman's coefficients of correlations between CD4 and CD8 TCR frequencies for HIV-negative and -positive subjects

| TCR | HIV-negative subjects (n = 84)a

|

HIV-positive subjects (n = 12)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | Adjusted P value | ρ | Adjusted P value | |

| Vβ 2 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.19 |

| Vβ 3 | 0.73 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.26 |

| Vβ 5a | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.83 |

| Vβ 5b | 0.12 | 0.31 | 0.43 | 0.39 |

| Vβ 5c | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.82 |

| Vβ 6 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.26 |

| Vβ 8a | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 0.26 |

| Vβ 8b | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.82 |

| Vβ 12 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.96 |

| Vβ 13 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.39 |

| Vβ 13.6 | 0.35 | 0.00 | −0.13 | 0.83 |

| Vβ 17 | 0.05 | 0.66 | −0.08 | 0.86 |

| Vβ 21 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 0.20 |

| Vβ 22 | 0.41 | 0.00 | −0.12 | 0.83 |

Spearman's coefficients of correlations (ρ) for TCR frequencies for HIV-negative and -positive subjects. P values that were zero or near zero are shown in boldface type.

Longitudinal analyses.

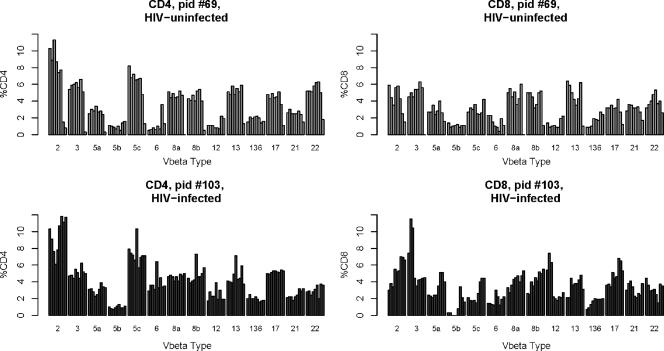

The longitudinal variation in the frequencies over time was assessed in HIV-infected and -uninfected children to determine the possible effects of chronic HIV exposure on the T-cell repertoire. Nonparametric methods were used in all statistical analyses because Vβ receptor frequencies were not normally distributed. Five HIV-exposed but uninfected and seven HIV-infected children were studied longitudinally, with seven repeated assays performed on each of the children over a 3-year period, starting at birth. Shown in Fig. 4 are representative child longitudinal assessments over seven intervals from each group (patient 69 [HIV exposed but uninfected] and patient 103 [HIV infected]). All the infected children developed plasma viral loads in excess of 500,000 copies/ml. Three of the seven established virologic control (i.e., <400 copies/ml) by 6 months of age. The remaining four were consistently viremic (i.e., >30,000 copies/ml of plasma) throughout the study period. Table 4 shows the intrapatient pairwise comparisons of the variability of Vβ cell receptor frequencies over time between CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells (as measured by the median of the IQRs of all Vβ cells over time). With the exception of patient 12, the variation exhibited within the CD4 compartment was no different than was seen in the CD8 compartment. This individual established complete HIV control by 6 months but was also coinfected with hepatitis C virus.

FIG. 4.

Representative longitudinal TCR frequencies of an HIV-uninfected (top) and HIV-infected individual (bottom). pid #69, patient identification number 69.

TABLE 4.

Intrapatient pairwise comparisons of the variability (as measured by IQR) of Vβ cell receptor frequencies over time between CD4 T cells and CD8 T cellsa

| Patient | HIV statusb | Median of IQRs of all Vβ cells over timea

|

Adjusted P valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 T cells | CD8 T cells | |||

| 1 | − | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.675 |

| 2 | − | 0.98 | 0.73 | 0.367 |

| 3 | − | 1.30 | 1.10 | 0.972 |

| 4 | − | 0.90 | 1.05 | 0.367 |

| 5 | − | 0.78 | 1.00 | 0.367 |

| 6 | + | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.233 |

| 7 | + | 1.70 | 2.00 | 0.972 |

| 8 | + | 0.90 | 1.50 | 0.207 |

| 9 | + | 1.08 | 1.25 | 0.818 |

| 10 | + | 0.78 | 1.33 | 0.164 |

| 11 | + | 1.10 | 0.65 | 0.164 |

| 12 | + | 0.50 | 1.55 | 0.036 |

Value is an indicator of the variability of Vβ TCR frequencies over time.

−, negative; +, positive.

The smallest adjusted P value is shown in boldface type.

Comparisons of changes over time in HIV-infected and -uninfected individuals.

Shown in Fig. 5 and Table 5 are the group interquartile variation over time in HIV-infected and -uninfected infants, shown separately for CD4 and CD8 TCRs. With the exception of one CD4 TCR (Vβ 12) and two CD8 TCRs (Vβ 3 and 5c), most of the variation is comparable in the two groups.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of changes (interquartile variation) (y axis) of TCRs over time in HIV-infected and -uninfected individuals. Boxplots of individual IQRs over time are shown. The black bars represent median values, the box ends denote IQRs (i.e., 25th and 75th percentiles), and the dashed lines extend to the 5th and 95th percentiles. The open circles represent extreme values.

TABLE 5.

Comparisons of changes over time in Vβ frequencies in CD4 and CD8 TCRs in HIV-infected and -uninfected individuals

| T-cell type and TCR | Median of IQRs over time for:

|

Unadjusted P value for diff.a | Adjusted P value for diff.a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-uninfected individuals (n = 5) | HIV-infected individuals (n = 7) | |||

| CD4 cells | ||||

| Vβ 2 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 0.87 | 1.00 |

| Vβ 3 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.34 | 0.69 |

| Vβ 5a | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.09 | 0.36 |

| Vβ 5b | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Vβ 5c | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.43 | 0.76 |

| Vβ 6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.34 | 0.69 |

| Vβ 8a | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.53 | 0.83 |

| Vβ 8b | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Vβ 12 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.05 | 0.36 |

| Vβ 13 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.15 | 0.42 |

| Vβ 13.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.68 | 0.95 |

| Vβ 17 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.74 | 0.95 |

| Vβ 21 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.10 | 0.36 |

| Vβ 22 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.10 | 0.36 |

| CD8 cells | ||||

| Vβ 2 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 0.11 | 0.50 |

| Vβ 3 | 0.4 | 3.1 | 0.01 | 0.14 |

| Vβ 5a | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Vβ 5b | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.76 | 0.94 |

| Vβ 5c | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.03 | 0.21 |

| Vβ 6 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.25 | 0.60 |

| Vβ 8a | 1.1 | 2.0 | 0.20 | 0.60 |

| Vβ 8b | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.46 | 0.81 |

| Vβ 12 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.88 | 0.94 |

| Vβ 13 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 0.76 | 0.94 |

| Vβ 13.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.22 | 0.60 |

| Vβ 17 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.53 | 0.83 |

| Vβ 21 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.87 | 0.94 |

| Vβ 22 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.42 | 0.81 |

Unadjusted and adjusted P values for the differences between the median IQR values for HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected patients.

DISCUSSION

This study addressed two separate questions. We asked what the TCR repertoire of newborns was like and whether there was a difference in this repertoire between HIV-exposed but uninfected and HIV-infected children. To demonstrate that the uninfected cohort was not different from the healthy (“normal”) cohort, we also looked at six cord blood specimens from HIV-uninfected mothers. The distribution of TCRs in these blood samples proved to be similar to the distribution of TCRs in blood samples from the HIV-exposed but uninfected cohort. We also asked whether the presence of HIV resulted in greater variation of the repertoire over the course of the first years after primary infection of the neonate.

TCRs are composed of α and β variable chains. The frequency distribution patterns of the CD4 and CD8 populations reflect the patterning of naïve cells, via negative and positive selection, once they leave the thymus and the effects of antigenic and supra-antigenic stimulation of both naïve and memory T cells. Since CD4 and CD8 cells that emerged from the thymus were at one point CD4+ CD8+ cells (double positive), these cells might have comparable frequencies of Vβ once they become single positive. With further “experience,” these cells might presumably diverge in their distribution as the individual ages. A variety of investigators have addressed the comparison of CD4 and CD8 TCR phenotypes. Among HIV-negative patients, there were significant differences between CD4 and CD8 cells for 10 out of the 14 β cell types, but for HIV-infected patients, there were no significant results. By examining the differences in median values of the CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells for the HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups, we can surmise that much of this difference in significance of results between the two groups is due to sample size.

Skewing of the repertoire has been suggested both as a selection event (positive or negative) occurring within the thymus and as a postthymic event. A study of the Vβ distribution on human thymic cells also revealed skewing with Vβ 5.1, 6.7, and 12 preferentially used in the CD4+ CD8− population (8). Positive selection within the murine thymus has been thought to be caused by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II determinants (17). Consistent with this rationale is that HLA-identical human twins showed similar patterns of V-gene frequencies, whereas HLA-mismatched twins were more different (9). Mls-like gene products have also been implicated in skewing murine repertoires by cross-linking nonpolymorphic MHC determinants (11, 12). Postthymic skewing could result from superantigen stimulation (13).

Most of the studies of the distribution of Vβ on CD4+ human T cells have been performed with mixed populations of adult individuals of various ages, and the observed repertoire may reflect the antigenic experience of each individual. To try to assess the effect of antigen exposure, Walser-Kuntz et al. looked at the usage of Vβ gene elements in CD45RO− CD4+ (naïve) T cells and compared it to that of CD45RO+ CD4+ (memory) T cells (25, 26). A correlation between Vβ gene segment usage, in this case Vβ 6.7 and also 5.1, and HLA-DRB1 alleles, specifically HLA-DRB1*04, could be demonstrated for the repertoire of the naive CD4+ T cells, suggesting a shaping force of the HLA-DRB1 allele on the peripheral TCR repertoire in the absence of antigen expansion. The influence of these MHC alleles on the repertoire of memory cells was less dramatic, and the authors surmise that this modulation reflects antigenic effects on cells after they have left the thymus. Other investigators have looked at Vβ usage in twins in an area where Plasmodium falciparum is endemic and, while observing that Vβ usage was more concordant within monozygotic twins, the repertoire for the entire group was similar to that for Caucasian populations not living in areas where malaria is endemic (23). A different approach to dissect the relative influence of HLA examined the pattern of the Vβ repertoire from allogeneic bone marrow recipients and their donors (either HLA matched or unrelated [16]). These authors noted that the correlation coefficient among the HLA-matched pairs was twice as good as that from unmatched pairs. However, 3 months after receiving marrow from HLA-matched siblings, the pattern in the recipient was more similar to the pattern seen pretransplant in the recipient than to the pattern of the donor, suggesting that both major and minor HLA antigens influence Vβ patterns. For economic reasons, we did not HLA type the children in this study; however, as noted above, this information would have been useful in interpreting some of our findings.

We found a bimodal distribution of Vβ 2. Others have also noted a bimodal distribution of Vβ 2 (3). These authors noted that individuals with low Vβ 2 CD4 T cells also had Vβ 2 distribution on their CD8 cells that clustered at the low end of frequencies measured. We also noted that individuals with Vβ 2 values on their CD4 cell populations of <2% had, with few exceptions, CD8 populations that were <2% (Fig. 1). It is not clear whether those with low Vβ 2 frequencies experienced clonal deletions in utero.

It could be argued that children born to HIV-infected mothers are not representative of healthy (“normal”) children despite not being HIV infected. In utero exposure to antigens of infected mothers may have skewed the repertoire of the fetus. We also examined the TCR distribution of six cord blood specimens of anonymous HIV-uninfected mothers and noted comparable distributions in both CD4 and CD8 populations, suggesting that our results are not influenced by maternal HIV infection. Other investigators have looked at the effect of birth on type 1 diabetic mothers and also found no influence on the TCR repertoire (18).

Previous research, beginning as early as a decade ago, has suggested that HIV may act as a superantigen, causing clonal deletions of different Vβ types (10). It has been argued that any observed deletion might result from a non-HIV immunogen present. A study of HIV effects on a murine SCID-hu mouse model raised in a pathogen-free environment suggested that HIV itself could act as a superantigen (2). We chose to look at the repertoire of newborn T cells, typically pathogen free, to rule out effects of competing superantigens. If HIV were not acting as a superantigen, it would be expected that there would be no selective loss of any particular CD4 Vβ type but a generalized effect on all types. Since the CD4 T-cell lymphoproliferative response to HIV is negligible in most infected individuals, there should be no specific expansion of Vβ types within this phenotype. While HIV does not produce destruction of CD8 T cells, the antigenic effect of HIV on CD8 might result in clonotypic expansions, perhaps subtle or even substantial enough to result in Vβ repertoire changes, particularly among separate subsets of naïve and memory cells (14, 15, 21). In our comparison of the TCR variations seen in seven HIV-infected and five HIV-uninfected children followed prospectively, we saw a trend but no statistically significant increased variation within the CD8 T-cell populations of the infected individuals. This would suggest that the effect of HIV on TCR was minimal in the small population of infants studied here. Possible explanations for this finding are that young infants have impaired CD8 cytotoxic immune responses to HIV (22), that they are infected by potential maternal escape mutants which may also evade the infant immune response (6), and that newborns have CD4 and CD8 T cells that are virtually all “naïve” and memory cells accumulate very slowly during the first few years of life (20).

Interfering in the natural history of HIV effects on the immune system by introducing antiretroviral therapy has been shown to largely reflect changes in the CD8 Vβ repertoire (5). One study found no TCR usage difference between HIV-infected and -uninfected Brazilians prior to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), but the development of an oligoclonal profile of Vβ changes without distinct patterns of usage after HAART in a subset of treated individuals (4). The study participants were adults who all started out with significant T-cell depression prior to therapy. All of the infected children in this study were treated with HAART during their first year of life prior to any significant destruction of T cells. While this may have affected the TCR repertoire, the previous study suggests that it may not have resulted in a large effect.

In summary, in this large survey of newborn TCR distribution, we have found substantial variability in the display of several types available for study using commercially available monoclonal antibodies. We have not determined the source of this variation, particularly the bimodal expression of Vβ 2 on CD4 cells. HIV-infected newborns demonstrated comparable distribution of these receptors on CD4 and CD8 T cells. Since about 70% of these children were uninfected at birth but were infected at 2 to 6 weeks of age, HIV could not have affected this distribution at birth. However, the subsequent changes over the course of infancy are generally not different from what is seen in the HIV-uninfected population, suggesting a minimal effect of HIV early in life in defining the expression of these receptors. Clonotyping these receptors may be a more sensitive tool for evaluating clonal deletions if they occur.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant M01 RR-00096 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamini, Y., and Y. Hochberg. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a powerful and practical approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 57289-300. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boldt-Houle, D. M., B. D. Jamieson, G. M. Aldrovandi, C. R. Rinaldo, Jr., G. D. Ehrlich, and J. A. Zack. 1997. Loss of T cell receptor Vbeta repertoire in HIV type 1-infected SCID-hu mice. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 13:125-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke, G. R., H. Reyburn, F. C. Lancaster, and A. W. Boylston. 1994. Bimodal distribution of V β 2+CD4+ T cells in human peripheral blood. Eur. J. Immunol. 24:837-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giacoia-Gripp, C. B., I. Neves, Jr., M. C. Galhardo, and M. G. Morgado. 2005. Flow cytometry evaluation of the T cell repertoire Vbeta repertoire among HIV-1 infected individuals before and after antiretroviral therapy. J. Clin. Immunol. 25:116-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorochov, G., A. U. Neumann, A. Kereveur, C. Parizot, T. Li, C. Katlama, M. Karmochkine, G. Raquin, B. Autran, and P. Debvre. 1998. Perturbation of CD4 and CD8 T-cell repertoires during progression to AIDS and regulation of the CD4 repertoire during antiretroviral therapy. Nat. Med. 4215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goulder, P. J., C. Brander, Y. Tang, C. Tremblay, R. A. Colbert, M. M. Addo, E. S. Rosenberg, T. Nguyen, R. Allen, A. Trocha, M. Altfeld, S. He, M. Bunce, R. Funkhouser, S. I. Pelton, S. K. Burchett, K. McIntosh, B. T. Korber, and B. D. Walker. 2001. Evolution and transmission of stable CTL escape mutations in HIV infection. Nature 412:334-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grunewald, J., C. H. Janson, and H. Wigzell. 1991. Biased expression of individual T cell receptor V gene segments in CD4+ and CD8+ human peripheral blood T lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 21:819-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grunewald, J., N. Shankar, H. Wigzell, and C. H. Janson. 1991. An analysis of alpha/beta TCR V gene expression in the human thymus. Int. Immunol. 3699-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gulwani-Akolkar, B., D. N. Posnett, J. Janson, C. H. Grunewald, H. Wigzell, P. Akolkar, K. Gregersen, and J. Silver. 1991. T cell receptor V-segment frequencies in peripheral blood T cells correlate with human leukocyte antigen type. J. Exp. Med. 174:1139-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imberti, L., A. Sottini, A. Bettinardi, M. Puott, and D. Primi. 1991. Selective depletion in HIV infection of T cells that bear specific T-cell receptor Vbeta sequences. Science 254860-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janeway, C. A., Jr., J. Yagi, P. J. Conrad, M. E. Katz, B. Jones, S. Vroegop, and S. Buxser. 1989. T-cell responses to Mls and to bacterial proteins that mimic its behavior. Immunol. Rev. 10761-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janeway, C. A., Jr., U. Dianzani, P. Portoles, S. Rath, E. P. Reich, J. Rojo, J. Yagi, and D. B. Murphy. 1989. Cross-linking and conformational change in T-cell receptors: role in activation and in repertoire selection. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 54:657-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kappler, J., B. Kotzin, L. Herron, E. W. Gelfand, R. D. Bigler, A. Boylston, S. Carrel, D. N. Posnett, Y. Choi, and P. Marrack. 1989. V β-specific stimulation of human T cells by staphylococcal toxins. Science 244:811-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kharbanda, M., T. W. McCloskey, R. Pahwa, M. Sun, and S. Pahwa. 2003. Alterations in T-cell receptor Vβ repertoire of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10:53-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kou, Z. C., J. S. Puhr, M. Rojas, W. T. McCormack, M. M. Goodenow, and J. W. Sleasman. 2000. T-cell receptor Vβ repertoire CD3 length diversity differs within CD45RA and CD45RO T-cell subsets in healthy and human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7953-959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lonial, S., C. Bomberger, and E. K. Waller. 2001. Changes in the pattern of TCR V β repertoire expression after bone marrow transplant is linked to the HLA haplotype in humans. Br. J. Haematol. 113:224-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald, H. R., R. K. Lees, R. Schneider, R. M. Zinkernagel, and H. Hengartner. 1988. Positive selection of CD4+ thymocytes controlled by MHC class II gene products. Nature 336:471-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manfras, B. J., S. Claudi-Boehm, R. Kreienberg, and B. O. Boehm. 2004. T-cell receptor repertoire and function in umbilical cord blood lymphocytes from newborns of type 1 diabetic mothers. Acta Diabetol. 41:167-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.R Development Core Team. 2006. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.Rproject.org.

- 20.Shearer, W. T., H. M. Rosenblatt, R. S. Gelman, R. Oyomopito, S. Plaeger, E. R. Stiehm, D. W. Wara, S. D. Douglas, K. Luzuriaga, E. J. McFarland, R. Yogev, M. H. Rathore, W. Levy, B. L. Graham, S. A. Spector, and the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group. 2003. Lymphocyte subsets in healthy children from birth through 18 years of age: the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group P1009 study. J. Allerg. Clin. Immunol. 112973-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soudeyns, H., P. Champagne, C. L. Holloway, G. U. Silvestri, N. Ringuette, J. Samson, N. Lapointe, and R.-P. Sekaly. 2000. Transient T cell receptor beta chain variable region-specific expansions of CD4 and CD8 T cells during the early phase of pediatric human immunodeficiency virus infection: characterization of expanded cell populations by T cell receptor phenotyping. J. Infect. Dis. 181:107-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiegel, H. M. L., R. Chandwani, M. E. Sheehy, J. Dobroszycki, G. Fennelly, A. Wiznia, J. Radding, M. Rigaud, H. Pollack, W. Borkowsky, M. Rosenberg, and D. F. Nixon. 2000. The impact of early initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) on the human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific CD8+ T cell response in children. J. Infect. Dis. 18288-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Troye-Blomberg, M., A. Fogdell, G. El-Ghazali, A. Larsson, M. Hassan King, F. Sisay-Joof, O. Olerup, J. Grunewald, and A. Jepson. 1997. Analysis of the T-cell receptor V β usage in monozygotic and dizogotic twins living in a P. falciparum endemic area in West Africa. Scand. J. Immunol. 45541-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van den Beemd, R., P. P. Boor, E. G. van Lochem, W. C. Hop, A. W. Langerak, I. L. Wolvers-Tettero, H. Hooijkaas, and J. J. van Dongen. 2000. Flow cytometric analysis of the Vβ repertoire in healthy controls. Cytometry 40:336-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walser-Kuntz, D. R., C. M. Weyand, J. W. Fulbright, S. B. Moore, and J. J. Goronzy. 1995. HLA-DRB1 molecules and antigenic experience shape the repertoire of CD4 T cells. Hum. Immunol. 44:203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walser-Kuntz, D. R., C. M. Weyand, A. J. Weaver, W. M. O'Fallon, and J. J. Goronzy. 1995. Mechanisms underlying the formation of the T cell receptor repertoire in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunity 2597-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]