Abstract

Ovariectomized Fischer (CDF-344) rats, with bilateral cannulae in the mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH) near the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMN), were used to test the hypothesis that serotonin receptors in the VMN contribute to the lordosis-inhibiting effects of mild restraint. Rats were hormonally primed with 10 μg estradiol benzoate (EB) followed 48 h later with sesame seed oil. Four to six h later (during the dark portion of the light-dark cycle), rats were pretested for sexual behavior. Thereafter, they were infused with saline, 2 μg of the serotonin (5-HT) 2 receptor agonist, (±)-2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl-2-aminopropane HCl (DOI), or 1 μg of the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, N-{2[4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1-piperazinyl]ethyl}-N-(2-pyridinyl) cyclohexanecarboxamide trihydrochloride (WAY100635). After a five min restraint, rats were tested for sexual receptivity. Rats infused with saline showed a significant decline in lordosis behavior after restraint. Infusion with either DOI or WAY100635 attenuated these effects of restraint. These findings extend earlier observations that the lordosis-disruptive effects of mild restraint include activation of 5-HT1A receptors in the VMN and are the first to implicate VMN 5-HT2 receptors in protection against mild restraint.

Keywords: female rats, serotonin, serotonin 2 receptors, serotonin 1A receptors, lordosis, ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus

1. Introduction

In prior experiments, we have used the lordosis reflex as a behavioral model for studying the role of serotonin (5-HT) receptors in the female’s successful adaptation to environmental challenge (Uphouse et al., 2003). The lordosis reflex is a supraspinal reflex made by sexually receptive female rats in response to sensory stimuli from the male and is necessary for successful reproduction to occur (Pfaff and Modianos, 1985). The reflex is dependent on estrogen and is facilitated by progesterone (Sodersten, 1981) and hormone action within the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMN) is crucial for elicitation of lordosis (Pfaff and Modianos, 1985). Within the VMN, serotonin (5-HT) exerts inhibitory control over female rat lordosis behavior (Uphouse, 2000). However, 5-HT’s role is complex with 5-HT1A receptor agonists inhibiting lordosis behavior while 5-HT2 receptor agonists may facilitate the behavior (Uphouse et al., 1992; Uphouse et al., 1993; Wolf et al., 1998b). Such facilitation is evident when ovariectomized rats receive hormone priming that is suboptimal for the elicitation of lordosis behavior (Uphouse et al., 1994a; Wolf et al., 1998b) or when sexual receptivity is reduced by coinfusion with 5-HT1A receptor agonists (Uphouse et al., 1994a).

We have suggested that this dual control by 5-HT1A and 5-HT2 receptors allows the female to (a) stop mating under conditions that may be substantially threatening to the female but (b) enable mating to continue under conditions that are only mildly stressful (Uphouse, 2000). Chronic stress is often associated with a breakdown in adaptive mechanisms including a decline in reproductive functioning (Dobson et al., 2003; Kalantaridou et al., 2004) while behavioral effects of acute mild stressful events may or may not lead to reproductive failure (Campbell et al., 1977; Gorzalka and Whalen, 1977; White and Uphouse, 2004). The female’s response to novel or potentially threatening stimuli depends on the degree of hormonal priming and the relative balance between 5-HT1A and 5-HT2 receptors (Sinclair-Worley and Uphouse, 2004; Uphouse, 2000; White and Uphouse, 2004) so that the effects of acute mild stress is a useful model for examining the mechanisms responsible for successful sexual adaptation during stress.

Our working model is that mild restraint reduces sexual behavior by enhancing 5-HT action at lordosis-inhibiting 5-HT1A receptors and that 5-HT2 receptors protect against this lordosis-inhibiting effect of restraint. Prior data are consistent with these suggestions. For example, five min of restraint reduced lordosis behavior in ovariectomized rats that had been primed with 10 μg EB (EO rats), but not in ovariectomized rats hormonally primed with 10 μg EB plus 500 μg progesterone (EP rats) (Truitt et al., 2003; Uphouse et al., 2003). However, when EP rats were injected prior to restraint with either the nonselective 5-HT2 receptor antagonist, ketanserin (ketanserin tartrate, 3-[2-[4-(4-fluorbenzoyl)-1-piperdinyl]ethyl]-2,4(1H,3H)-quinazolinedione), or the 5-HT2C receptor antagonist, 5-methyl-1-(3-pyridylcarbamoyl)-1,2,3,5-tetrahydropyrrolo[2,3-f]indole (SB 206553), EP rats responded like EO rats (e.g. lordosis behavior was reduced by the restraint) (Uphouse et al., 2003). However, the effects of a 5-HT1A receptor agonist on lordosis behavior of EP rats were also amplified by mild restraint (Uphouse et al., 2003), consistent with prior suggestions that mild restraint inhibits lordosis behavior by activating 5-HT1A receptors in the VMN. These findings led us to speculate that the greater vulnerability of EO females, relative to EP females, to restraint-induced lordosis decline resulted from a heightened activation of 5-HT1A receptors and a lower activation of 5-HT2 receptors in the VMN. If so, then the infusion of either a 5-HT1A receptor antagonist or a 5-HT2 receptor agonist should prevent the effects of restraint on lordosis behavior of EO rats.

The current experiment was designed to test these hypotheses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

Disposable Decapicones® restrainers were purchased from Braintree Scientific Inc. (Braintree, MA). The 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist, DOI, the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, WAY100635, estradiol benzoate (EB), and sesame seed oil were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Isoflurane (AErrane®) was obtained from Henry Schein (Baxter Labs, Deerfield, IL). Suture materials were purchased from Henry Schein (Melville, NY). All other materials were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Houston, TX).

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Animals and housing

Female Fischer (CDF-344) rats were purchased as adults or were bred in the TWU animal facility from stock obtained from Charles Rivers Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Rats were housed 2 or 3 per cage in polycarbonate shoebox cages in a colony room maintained at 25°C and 55% humidity, with lights on from 12 midnight to 12 noon. Food and water were available ad lib. All procedures were conducted according to PHS policy and were approved by the IACUC at Texas Woman’s University.

2.2.2 Surgical procedures and hormone treatments

Females, weighing between 140 and 170 g (approximately 60 to 90 days of age), were anesthetized with AErrane® and stereotactically implanted bilaterally with 22-gauge stainless steel cannulae directed toward the VMN (atlas coordinates AP 4.38; DV - 7.8; ML ± 0.4 from König and Klippel (König and Klippel, 1963) as previously described (Uphouse et al., 1992). Two weeks later, rats were ovariectomized under AErrane® anesthesia. Two weeks later, females were injected with 10 μg of EB followed 48 h later with sesame seed oil. Injections were given subcutaneously (s.c.) in a volume of 0.1 ml/rat.

2.2.3 Testing for sexual receptivity and intracranial infusions

On the morning of testing (prior to lights out), rats were moved to the testing room where the males were housed. Testing for sexual behavior, as previously described (Uphouse et al., 1992), was initiated within one to three h after colony lights off and four to six h after the oil injection. Visibility was aided by red lighting. In the pretest for sexual receptivity, females were placed in the home cages of sexually experienced Sprague-Dawley male rats and behavior was monitored until the male had accomplished 10 mounts; rats with a pretest lordosis to mount (L/M) ratio of 0.7 or higher were included in the remaining experiments. Lordosis quality, as previously described (Hardy and DeBold, 1971; Uphouse et al., 1992), was also recorded.

After the pretest, rats were infused intracranially with saline, 2.0 μg DOI, or 1.0 μg WAY100635. These concentrations of DOI and WAY100635 were previously shown to attenuate the lordosis-inhibiting effects of a 5-HT1A receptor agonist (Uphouse et al., 1994a; Uphouse and Wolf, 2004). Infusions were delivered at a rate of 0.24-0.26 μl/min to a final infusion volume of 0.5 μl per cannula. On the basis of our prior studies (Uphouse et al., 1993; Uphouse et al., 1991), we have estimated diffusion distances to be less than 0.3 mm laterally and ventrally from the cannula tip.

Intracranial drug concentrations are indicated as the amount of drug infused through each bilateral cannula or one-half the concentration per animal. Six min after infusion with DOI, rats were placed in Decapicones® for five min. For WAY100635, the infusion occurred during the five min restraint. Saline infusion conditions were matched to the drug and later pooled for analysis. For all three conditions, rats were placed in the male’s cage immediately after restraint. Sexual behavior testing was for 30 consecutive min as previously described (Uphouse et al., 2003).

2.2.4 Restraint procedures

For restraint, the female was placed head first into the Decapicone® so that her nose was flush with the small opening at the tip of the cone. A longitudinal slit was made along the cone to allow room for the top of the guide cannulae. The slit was then secured with lab tape after the female’s nose was flush with the air hole. The base of the cone was gathered around the female’s tail and secured tightly with tape. The process of wrapping the female required between 30 and 60 sec. The wrapped female was set aside for five min.

2.2.5 Histological procedures

After behavioral testing, rats were anesthetized with AErrane® and perfused with 0.9% saline followed by 10% buffered formalin. Brain tissue was placed into 10% buffered formalin for at least 24 h before sectioning. Coronal sections (100 μm) were stained with cresyl violet and examined for cannulae placement according to the atlas of König and Klippel (König and Klippel, 1963). Data from rats with cannulae in the mediobasal hypothalamus in the vicinity of the VMN were included in the study. Rats with misplaced cannulae were excluded from data analyses.

2.2.6 Statistical procedures

For statistical purposes, L/M ratios or lordosis quality scores were grouped into the pretest interval and five-min intervals after restraint. Data were evaluated by repeated measures ANOVA with type of infusion as the independent factor. Differences between treatment groups, within time intervals, were compared with Tukey’s test. Comparisons within groups, across time after restraint, were made with Dunnett’s test to the pretest interval. The statistical reference was Zar (Zar, 1999), and an alpha level of 0.05 was required for rejection of the null hypothesis.

3. Results

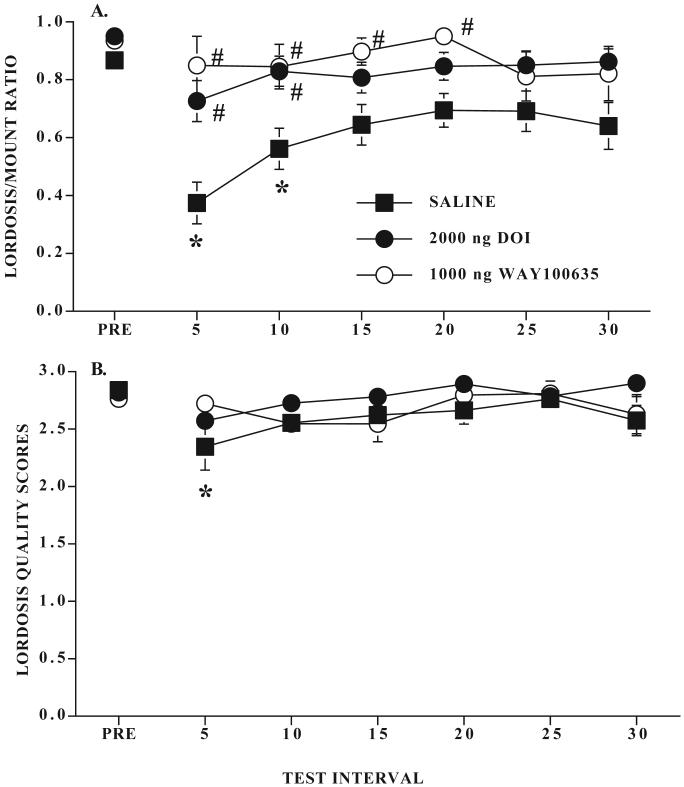

L/M ratios from rats infused with saline, 2.0 μg DOI, or 1.0 μg WAY100635 are shown in Figure 1A. Only rats with cannulae located near the VMN were included in the data analysis. In agreement with prior studies (Uphouse et al., 2003; White and Uphouse, 2004), five min restraint significantly reduced lordosis behavior. VMN infusion with either 2.0 μg DOI or 1.0 μg WAY100635 attenuated this decline in lordosis behavior. Out of the 16 rats infused with saline during restraint, 14 showed a decline in lordosis behavior. In contrast, only 4 of the 12 rats infused with DOI showed such a decline. One rat infused with DOI had both cannulae located slightly anterior to the VMN and was excluded from the ANOVA but this rat did not show a decline in lordosis behavior. Every rat infused with WAY100635 into the VMN showed protection from the restraint-induced decline in lordosis behavior. Three rats infused with WAY100635 had their cannulae located outside the VMN and were excluded from the ANOVA. All three of these rats showed a decline in lordosis behavior after restraint.

Figure 1. Effects of DOI and WAY100635 on sexual receptivity after 5 min restraint.

Ovariectomized rats with bilateral cannulae near the VMN were hormonally primed with 10 μg estradiol benzoate followed by sesame seed oil. After a pretest for sexual receptivity, rats were infused with saline, DOI, or WAY100635 (Ns respectively are 16, 12 and 6) and restrained for five min as described in the Methods. Data in 1A and 1B are the mean ± S.E. lordosis to mount (L/M) ratios and lordosis quality scores, respectively, for the pretest interval (PRE) and 6 consecutive five min intervals after restraint. * indicates intervals where the L/M ratio was significantly different from the pretest. # indicates intervals where rats infused with DOI or WAY100635 differed significantly from the saline group.

There were significant effects of treatment (F2,31 = 10.92, P ≤ 0.0003) and time (F6,186 = 4.99, P ≤ 0.0001) on lordosis behavior. Overall, saline-treated rats were significantly different from both DOI and WAY100635 infused rats (respectively, Tukey’s q31,3 = 5.54 and 6.51, P ≤ 0.05). Saline treated rats differed significantly from their pretest interval at five and 10 min after restraint and were significantly different from DOI and WAY100635 infused rats, respectively, at the five and 10 min and five through 20 min intervals (all q ≥ 2.8, all P ≤ 0.05).

There was also a small, but significant, time-dependent decline in lordosis quality after restraint (F1,186 = 2.7, P ≤ 0.05) but there was neither a significant treatment effect nor a significant interaction between time and treatment (all P > 0.05; Fig 1B). With posthoc comparisons, only for the saline-infused rats was the decline in lordosis quality statistically significant (Tukey’s q186,7 ≥ 2.8, P ≤ 0.05).

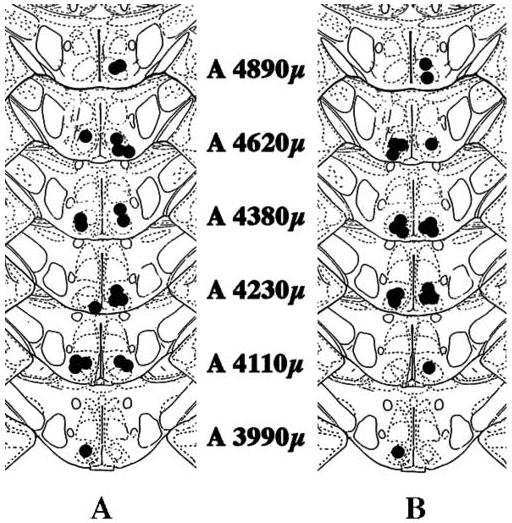

Cannulae locations from rats infused with WAY100635 or DOI are shown in Figure 2. A representative section is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2. Location of cannulae in rats infused with saline or DOI.

In the figure are shown cannulae locations for rats used in this experiment. Coronal sections are taken from König and Klippel (1963). Numbers in the figure refer to atlas locations. Cannula location was assigned to the brain section containing the most ventral location of the cannula track. In 2A and 2B, filled circles on the right side of each section indicate bilateral locations from rats that were infused with saline. Filled circles on the left of 2A indicate bilateral locations from rats that were infused with DOI. Filled circles on the left of 2B indicate bilateral locations from rats that were infused with WAY100635.

Figure 3. A representative section of cannulae locations in the VMN.

The figure represents a section through the VMN where infusion cannulae were located. The section was treated as described in the Methods.

The average number of mounts by the male for saline, DOI, and WAY100635-treated rats, respectively, was 8.39 ± 0.54, 8.29 ± 0.43, and 7.07 ± 0.64 per test interval and there were no significant differences among the three infusion conditions (F1,144 = 3.2, P > .05).

4. Discussion

In previous experiments, we reported that five min restraint reduced lordosis behavior of rats hormonally primed only with estrogen (EO rats) but not in rats primed with estrogen and progesterone (EP rats) (Uphouse et al., 2003; White and Uphouse, 2004). However, systemic treatment with either ketanserin or the 5-HT2B/2C receptor antagonist, SB 206553, did allow reduction of lordosis behavior in EP rats after restraint (Uphouse et al., 2003). The current study was designed to determine if an EO rat’s response to restraint could be modified by 5-HT receptor compounds so that the EO rat’s behavior resembled that of rats primed with both hormones.

We have hypothesized that the reduced lordosis behavior after restraint reflects a stress-induced enhancement of 5-HT1A receptor activation within the VMN due to an increased release of 5-HT in response to the stress (Uphouse et al., 2003). Although effects of such a mild restraint on extracellular 5-HT have not been examined, various stressors (including restraint) increase extracellular 5-HT in a variety of brain areas, including the hypothalamus (Kirby et al., 1997; Shimizu et al., 1992). The current findings that the effects of restraint were attenuated by prior infusion with a 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, WAY100635, add support to this hypothesis.

Both estrogen and progesterone influence functioning of the 5-HT system (Bethea et al., 2002). Ovariectomized rats treated with estrogen and progesterone are less sensitive to the lordosis-inhibiting effects of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist, 8-OH-DPAT, as the priming dose of estrogen increases (Jackson and Uphouse, 1996; Jackson and Uphouse, 1998; Trevino et al., 1999; Uphouse et al., 1994b). Progesterone also reduces the inhibitory effect of 8-OH-DPAT on lordosis behavior (Truitt et al., 2003). Moreover, lower doses of 8-OH-DPAT inhibit lordosis behavior in hormone-primed ovariectomized rats than are required the reduce the behavior in naturally-cycling proestrous rats (Jackson and Uphouse, 1996; Truitt et al., 2003; Uphouse et al., 1992). Thus, hormonal priming may influence the response to mild restraint by reducing the activation of 5-HT1A receptors following restraint.

The mechanisms whereby such attenuation occurs is not yet clear. However, there is considerable evidence that estrogen can uncouple 5-HT1A receptors from their G-proteins (Bethea et al., 2002; Mize and Alper, 2000; Mize et al., 2001; Raap et al., 2000) so that higher concentrations of agonist would be required to mediate effects of the receptor. Given the inhibitory effect of 5-HT1A receptors on lordosis behavior, it might be anticipated that 5-HT1A receptors would be completely desensitized in sexually receptive females. However, this does not appear to be the case [for review, see Uphouse (Uphouse, 2000)]. Instead, sexually receptive females have less extracellular 5-HT available for activation of 5-HT1A receptors and progesterone may be responsible for this decline in 5-HT (Farmer et al., 1996; Maswood et al., 1999).

Alternatively, it has been suggested that hormonal priming enhances the density of 5-HT2 receptors (Cyr et al., 1998; Sumner and Fink, 1993; Sumner and Fink, 1995; Sumner and Fink, 1997; Sumner et al., 1999) but evidence that this occurs within the VMN is lacking. Nevertheless, there is evidence that hormonal treatment alters the effect of VMN infusion with 5-HT2 receptor compounds. The nonselective 5-HT2 receptor antagonist, ketanserin, although able to inhibit lordosis behavior following infusion into the VMN, is less effective in EP than in EO rats (Uphouse, 2000) and the inhibitory effect of the 5-HT2A/2C receptor antagonist, SB206553, is reduced by an increase in hormonal priming (Sinclair-Worley and Uphouse, 2004). Moreover, since agonist activation of 5-HT2 receptors in the VMN facilitates lordosis behavior (Wolf et al., 1999; Wolf et al., 1998a) and attenuates the effects of 5-HT1A receptor agonists (Maswood et al., 1996; Uphouse et al., 1994a), an increased effectiveness of these receptors in the VMN could attenuate the effects of restraint on 5-HT1A receptor activation. DOI’s ability to reduce the effects of mild restraint on lordosis behavior in EO rats, as shown in the current experiment, is consistent with such a possibility.

How DOI attenuates the effects of 5-HT1A receptor activation is not known. However, a 5-HT2 receptor-mediated increase in protein kinase C (PKC) may be involved. 5-HT2 receptors are G-protein coupled receptors, the activation of which increases diacylglycerol and inositol triphosphate and leads to elevations in PKC (Leysen, 2004). 5-HT1A receptors can be phosphorylated by PKC leading to a reduction in functional effectiveness of 5-HT1A receptors (Raymond, 1991). Therefore, DOI may reduce effects of 5-HT1A receptor activation via a 5-HT2 receptor-mediated increase in PKC. In support of this possibility is a recent observation from our laboratory that DOI’s ability to attenuate the lordosis-inhibiting effect of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist, 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino) tetralin (8-OH-DPAT), was blocked by a PKC inhibitor, bisindolymaleimide I hydrochloride (BIM) (Selvamani et al., 2007).

Previously, we reported that VMN infusion with the 5-HT2 receptor antagonist, ketanserin, did not potentiate effects of restraint in ovariectomized rats hormonally primed with estrogen and progesterone (Uphouse et al., 2003). These data led us to suggest that the site of 5-HT2 receptor modulations of the effects of restraint included sites outside the VMN. The current findings, in contrast, allow the suggestion that activation of 5-HT2 receptors in the VMN may be sufficient to attenuate lordosis-inhibiting effects of five min restraint in rats primed only with estrogen.

In summary, mild restraint reduced lordosis behavior of rats hormonally primed only with estrogen. Such lordosis-inhibition was attenuated by a 5-HT2 receptor agonist and completely eliminated by blocking 5-HT1A receptors.

Acknowledgements

Special appreciation is given to Mr. Dan Wall and Ms. Karolina Blaha-Black for animal care and to Dr. Nathaniel Mills for assistance with imaging. The research was supported by NIH R01 HD28419 and GM 55380 and by the Department of Biology at Texas Woman’s University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bethea CL, Lu NZ, Gundlah C, Streicher JM. Diverse actions of ovarian steroids in the serotonin neural system. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2002;23(1):41–100. doi: 10.1006/frne.2001.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell GA, Kurcz M, Marshall S, Meites J. Effects of starvation in rats on serum levels of follicle stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, thyrotropin, growth hormone and prolactin; response to LH-releasing hormone and thyrotropin-releasing hormone. Endocrinology. 1977;100(2):580–7. doi: 10.1210/endo-100-2-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr M, Bosse R, Di Paolo T. Gonadal hormones modulate 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptors: emphasis on the rat frontal cortex. Neuroscience. 1998;83(3):829–36. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00445-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson H, Ghuman S, Prabhakar S, Smith R. A conceptual model of the influence of stress on female reproduction. Reproduction. 2003;125(2):151–63. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1250151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer CJ, Isakson TR, Coy DJ, Renner KJ. In vivo evidence for progesterone dependent decreases in serotonin release in the hypothalamus and midbrain central grey: relation to the induction of lordosis. Brain Res. 1996;711(12):84–92. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorzalka BB, Whalen RE. The effects of progestins, mineralocorticoids, glucocorticoids, and steroid solubility on the induction of sexual receptivity in rats. Horm Behav. 1977;8(1):94–9. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(77)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy DF, DeBold JF. The relationship between levels of exogenous hormones and the display of lordosis by the female rat. Horm Behav. 1971;2:287–297. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A, Uphouse L. Prior treatment with estrogen attenuates the effects of the 5-HT1A agonist, 8-OH-DPAT, on lordosis behavior. Horm Behav. 1996;30(2):145–52. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1996.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A, Uphouse L. Dose-dependent effects of estradiol benzoate on 5-HT1A receptor agonist action. Brain Res. 1998;796(12):299–302. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantaridou SN, Makrigiannakis A, Zoumakis E, Chrousos GP. Stress and the female reproductive system. J Reprod Immunol. 2004;62(12):61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby LG, Chou-Green JM, Davis K, Lucki I. The effects of different stressors on extracellular 5-hydroxytryptamine and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid. Brain Res. 1997;760(12):218–30. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König J, Klippel R. “The Rat Brain. A Stereotaxic Atlas of the Forebrain and Lower Parts of the Brain Stem.”. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Leysen JE. 5-HT2 receptors. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2004;3(1):11–26. doi: 10.2174/1568007043482598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maswood S, Andrade M, Caldarola-Pastuszka M, Uphouse L. Protective actions of the 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist, DOI, on 5-HT1A receptor-mediated inhibition of lordosis behavior. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35(4):497–501. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maswood S, Truitt W, Hotema M, Caldarola-Pastuszka M, Uphouse L. Estrous cycle modulation of extracellular serotonin in mediobasal hypothalamus: role of the serotonin transporter and terminal autoreceptors. Brain Res. 1999;831(12):146–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mize AL, Alper RH. Acute and long-term effects of 17beta-estradiol on G(i/o) coupled neurotransmitter receptor function in the female rat brain as assessed by agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPgammaS binding. Brain Res. 2000;859(2):326–33. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)01998-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mize AL, Poisner AM, Alper RH. Estrogens act in rat hippocampus and frontal cortex to produce rapid, receptor-mediated decreases in serotonin 5-HT(1A) receptor function. Neuroendocrinology. 2001;73(3):166–74. doi: 10.1159/000054633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff DW, Modianos D. Neural mechanisms of female reproductive behavior. In: Adler D, Pfaff D, Goy RW, editors. Handbook of behavioral neurobiology”. Plenum Press; New York: 1985. pp. 423–493. [Google Scholar]

- Raap DK, DonCarlos L, Garcia F, Muma NA, Wolf WA, Battaglia G, Van de Kar LD. Estrogen desensitizes 5-HT(1A) receptors and reduces levels of G(z), G(i1) and G(i3) proteins in the hypothalamus. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39(10):1823–32. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond JR. Protein kinase C induces phosphorylation and desensitization of the human 5-HT1A receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(22):14747–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvamani A, Lincoln C, Uphouse L.The PKC inhibitor, bisindolymaleimide, blocks DOI’s attenuation of the effects of 8-OH-DPAT on female rat lordosis behavior Pharmacol Biochem Behav submitted 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu N, Take S, Hori T, Oomura Y. In vivo measurement of hypothalamic serotonin release by intracerebral microdialysis: significant enhancement by immobilization stress in rats. Brain Res Bull. 1992;28(5):727–34. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90252-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair-Worley L, Uphouse L. Effect of estrogen on the lordosis-inhibiting action of ketanserin and SB 206553. Behav Brain Res. 2004;152(1):129–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodersten P. Estradiol-progesterone interactions in the reproductive behavior of female rats. In: Ganten D, Pfaff D, editors. Current Topics in Neuroendocrinology: Actions of Progesterone on the Brain.”. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1981. pp. 141–174. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner BE, Fink G. Effects of acute estradiol on 5-hydroxytryptamine and dopamine receptor subtype mRNA expression in female rat brain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1993;4:83–92. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1993.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner BE, Fink G. Estrogen increases the density of 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptors in cerebral cortex and nucleus accumbens in the female rat. J. Steroid. Biochem. Molec. Biol. 1995;54:15–20. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00075-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner BE, Fink G. The density of 5-hydoxytryptamine2A receptors in forebrain is increased at pro-oestrus in intact female rats. Neurosci Lett. 1997;234(1):7–10. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00651-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner BE, Grant KE, Rosie R, Hegele-Hartung C, Fritzemeier KH, Fink G. Effects of tamoxifen on serotonin transporter and 5-hydroxytryptamine(2A) receptor binding sites and mRNA levels in the brain of ovariectomized rats with or without acute estradiol replacement. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;73(12):119–28. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevino A, Wolf A, Jackson A, Price T, Uphouse L. Reduced efficacy of 8-OH-DPAT’s inhibition of lordosis behavior by prior estrogen treatment. Horm Behav. 1999;35(3):215–23. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truitt W, Harrison L, Guptarak J, White S, Hiegel C, Uphouse L. Progesterone attenuates the effect of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist, 8-OH-DPAT, and of mild restraint on lordosis behavior. Brain Res. 2003;974(12):202–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uphouse L. Female gonadal hormones, serotonin, and sexual receptivity. Brain Res Rev. 2000;33(23):242–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uphouse L, Andrade M, Caldarola-Pastuszka M, Maswood S. Hypothalamic infusion of the 5-HT2/1C agonist, DOI, prevents the inhibitory actions of the 5-HT1A agonist, 8-OH-DPAT, on lordosis behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994a;47(3):467–70. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uphouse L, Caldarola-Pastuszka M, Maswood S, Andrade M, Moore N. Estrogen-progesterone and 8-OH-DPAT attenuate the lordosis-inhibiting effects of the 5-HT1A agonist in the VMN. Brain Res. 1994b;637(12):173–80. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uphouse L, Caldarola-Pastuszka M, Montanez S. Intracerebral actions of the 5-HT1A agonists, 8-OH-DPAT and buspirone and of the 5-HT1A partial agonist/antagonist, NAN-190, on female sexual behavior. Neuropharmacology. 1992;31(10):969–81. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(92)90097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uphouse L, Caldarola-Pastuszka M, Moore N. Inhibitory effects of the 5-HT1A agonists, 5-hydroxy- and 5-methoxy-(3-di-n-propylamino)chroman, on female lordosis behavior. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32(7):641–51. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90077-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uphouse L, Montanez S, Richards-Hill R, Caldarola-Pastuszka M, Droge M. Effects of the 5-HT1A agonist, 8-OH-DPAT, on sexual behaviors of the proestrous rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;39(3):635–40. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90139-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uphouse L, White S, Harrison L, Hiegel C, Majumdar D, Guptarak J, Truitt WA. Restraint accentuates the effects of 5-HT2 receptor antagonists and a 5-HT1A receptor agonist on lordosis behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;76(1):63–73. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uphouse L, Wolf A. WAY100635 and female rat lordosis behavior. Brain Res. 2004;1013(2):260–3. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White S, Uphouse L. Estrogen and progesterone dose-dependently reduce disruptive effects of restraint on lordosis behavior. Horm Behav. 2004;45(3):201–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A, Caldarola-Pastuszka M, DeLashaw M, Uphouse L. 5-HT2C receptor involvement in female rat lordosis behavior. Brain Res. 1999;825(12):146–51. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A, Caldarola-Pastuszka M, Uphouse L. Facilitation of female rat lordosis behavior by hypothalamic infusion of 5-HT(2A/2C) receptor agonists. Brain Res. 1998a;779(12):84–95. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A, Jackson A, Price T, Trevino A, Caldarola-Pastuszka M, Uphouse L. Attenuation of the lordosis-inhibiting effects of 8-OH-DPAT by TFMPP and quipazine. Brain Res. 1998b;804(2):206–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zar J. “Biostatistical Analysis.”. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1999. [Google Scholar]