Abstract

Goods-based contingency management interventions (e.g., those using vouchers or prizes as incentives) have demonstrated efficacy in reducing cocaine use, but cost has limited dissemination to community clinics. Recent research suggests that development of a cash-based contingency management approach may improve treatment outcomes while reducing operational costs of the intervention. However, the clinical safety of providing cash-based incentives to substance abusers has been a concern. The present 16-week study compared the effects of goods-based versus cash-based incentives worth $0, $25, $50, and $100 on short-term cocaine abstinence in a small sample of cocaine-dependent methadone patients (N=12). A within-subject design was used; a 9-day washout period separated each of 8 incentive conditions. Higher magnitude ($50 and $100) cash-based incentives (checks) produced greater cocaine abstinence compared with the control ($0) condition, but a magnitude effect was not seen for goods-based incentives (vouchers). A trend was observed for greater rates of abstinence in the cash-based versus goods-based incentives at the $50 and $100 magnitudes. Receipt of $100 checks did not increase subsequent rates of cocaine use above those seen in control conditions. The efficacy and safety data provided in this and other recent studies suggest that use of cash-based incentives deserves consideration for clinical applications of contingency management, but additional confirmation in research using larger samples and more prolonged periods of incentive delivery is needed.

Keywords: contingency management, abstinence incentives, contingent reinforcement, cocaine dependence

Contingency management is a behavioral modification strategy shown to improve treatment outcomes in drug abusers (for a review, see Budney, Sigmon, & Higgins, 2001; Higgins, Alessi, & Dantona, 2002). Based on principles of learning and conditioning, contingency management interventions use motivational incentives to facilitate behavior change (e.g., drug abstinence, clinic attendance). Adding contingency management to psychosocial treatments for drug dependence has improved treatment retention and abstinence rates during and after treatment in controlled clinical trials for the treatment of alcohol, cocaine, marijuana, nicotine, and opioid dependence (Higgins et al., 2002).

Two predominant strategies for incentive delivery have emerged in contingency management interventions for drug dependence. One strategy is the voucher-based incentive approach developed by Higgins and colleagues to treat cocaine dependence (Higgins et al., 1993, 1994; Higgins, Wong, Badger, Ogden, & Dantona, 2000). In this approach, patients earn vouchers with predetermined monetary values for meeting treatment goals. To promote more sustained behavior change, voucher values increase the longer the patient continues to perform the target behavior (e.g., cocaine abstinence) and reset to a lower value once there is a break in that behavior (e.g., cocaine use). Throughout treatment, earned vouchers are added into a patient account and can be exchanged for retail goods and services. Clinic staff work with patients to determine appropriate ways to spend their voucher earnings, and the staff then purchase items in the community for the patients.

A second incentive delivery strategy is the prize-draw approach developed by Petry and colleagues (Petry & Martin, 2002; Petry, Martin, Cooney, & Kranzler, 2000). In this approach, participants earn the opportunity to directly receive retail items (prizes) rather than receiving a secondary reinforcer (vouchers) that must later be exchanged. Similar to the voucher approach, extended periods of uninterrupted behavior change (e.g., abstinence) are rewarded with increased opportunities to earn prizes. Prizes valued between $1 and $100 are kept on-site, with a variety of prize choices offered. The prize-based approach is unique when compared with vouchers because it is possible for patients to earn high-magnitude incentives early in treatment. However, only about half of patient draws yield a prize, whereas the remaining draws contain slips of paper that say “Good job, try again.”

Both of these goods-based incentive approaches (vouchers and prizes) have comparable efficacy in obtaining high rates of treatment retention and drug abstinence (Petry, Alessi, Marx, Austin, & Tardif, 2005); however, translation of either approach to community treatment clinics has been limited, with cost usually cited as the primary feasibility limitation (Kirby, Benishek, Dugosh, & Kerwin, 2006). Reducing the cost of contingency management interventions further is therefore desirable to enhance dissemination to community clinics. Minimizing staff time spent obtaining the incentives and managing the voucher accounts or prize-drawing system is one particularly attractive cost-reduction strategy. The operational cost of staff time is typically high, with frequent trips to purchase incentives. The alternative cost-cutting strategy of reducing the value of incentives (direct cost) may result in reduced treatment efficacy (Dallery, Silverman, Chutuape, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 2001; Silverman, Chutuape, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 1999) and so is not an attractive option.

One approach that has been relatively unexplored is the use of cash-based incentives (cash or check payments). There are several reasons to believe that cash-based incentives would have advantages over goods-based incentives. First, use of cash-based incentives would likely significantly reduce operational costs associated with staff time spent off-site compared with voucher- or prize-based incentives. In addition, there is evidence that cash is a more potent reinforcer compared with vouchers. This suggestion is based on findings from two human choice studies, one that showed a preference among pregnant drug-dependent women for cash over voucher incentives of comparable magnitude (Rosado, Sigmon, Jones, & Stitzer, 2005) and another in which cash was better able than vouchers of equal value to compete with cocaine self-administration (Hart, Haney, Foltin, & Fischman, 2000). It is not clear whether this advantage would extend to check payments because of the delay and response cost required to exchange the check for cash. Last, cash-based incentives have the advantage of being more flexible for the recipient compared with goods-based incentives: Cash is not limited in the type of goods or services that can be obtained, it can be used at any time, and it does not require a prior commitment to a particular purchase.

Despite the potential advantages of cash-based incentives, several concerns need to be addressed before they are used clinically. Of primary concern is that substance abusers receiving cash-based incentives could use their incentives to purchase drugs or engage in other activities that may negatively impact treatment goals. However, there is little empirical evidence on this subject. Two recent studies suggest that cash incentives pose no greater risk of new drug use compared with noncash alternatives and that they may actually be associated with clinical benefits. Festinger et al. (2005) randomly assigned drug treatment patients to receive cash or gift certificate payments for completing a 6-month follow-up assessment. Participants offered cash were significantly more likely to complete the follow-up visit compared with those offered gift certificates. Further, a safety assessment conducted the week after receipt of the incentives indicated that rates of new drug use were low and did not differ by incentive type. In another study, Drebing, Van Ormer, and Krebs (2005) observed significant improvements in drug- and employment-related outcomes when a cash-based contingency management intervention was added to a vocational rehabilitation program for dually diagnosed veterans.

The current study extends prior research on the relative reinforcing efficacy of cash-based versus goods-based incentives and assesses the safety of providing cash-based incentives by examining effects on subsequent drug use. Understanding the relative efficacy and safety of cash-based incentives for therapeutic gains in substance abusers may be an important step in our attempts to maximize the success and dissemination of contingency management interventions in substance abusers.

Method

Participants

Participants were 12 patients (10 female, 2 male) enrolled in the methadone treatment clinic at the Johns Hopkins University Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit in Baltimore, Maryland, who had demonstrated problematic use of cocaine during the course of their treatment for opiate dependence. The group composition was 75% African American and 25% Caucasian. On average, participants were 41 years old (SD = 4), had 12 years of education (SD = 1), and had been on methadone maintenance for 16 months (SD = 11) at the time of study admission. Three were employed part time during the study, the rest were unemployed. All participants met criteria for cocaine dependence as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev.; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). In the 2 weeks prior to study admission, 76% of thrice-weekly urine samples were cocaine positive (>300 ng/mL benzoylecgonine). Self-report diaries obtained at intake and during the study indicated that smoked crack cocaine was the predominant route of cocaine administration in this sample.

Experimental Design

A within-subject design using the brief abstinence test (BAT) model (Robles et al., 2000) was used rather than a clinical trial approach in order to test multiple experimental conditions in a short period of time. The protocol lasted 16 weeks and included eight experimental conditions. Each experimental condition consisted of a 5-day BAT during which incentives could be earned twice for cocaine abstinence, and was followed by a 9-day washout period during which cocaine use was monitored but no incentives could be earned for abstinence. The type (voucher vs. check) and magnitude ($0, $25, $50, or $100) of incentive that participants could earn for abstaining from cocaine was manipulated across the eight study conditions. Exposure to incentive type (voucher or check) occurred in two counterbalanced blocks, each lasting 8 weeks. Within these blocks participants were exposed to each of the incentive magnitudes ($0, $25, $50, and $100) in a randomized order. Throughout the study, participants continued usual treatment for opiate dependence, which included daily methadone and group and individual counseling.

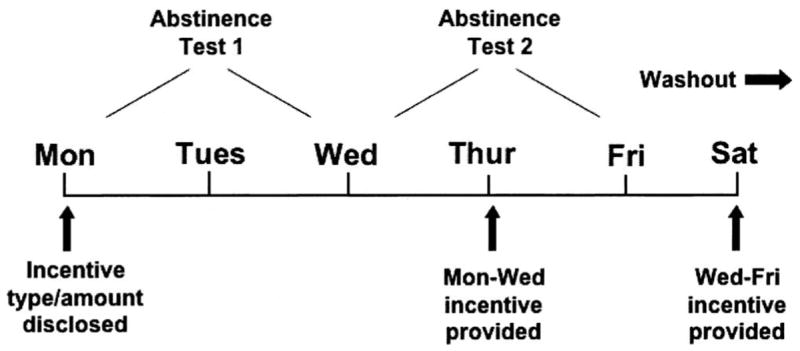

Figure 1 shows the procedures during the 5-day abstinence test intervention. On Monday of each study condition, participants were informed of the incentive type (voucher or check) and magnitude ($0, $25, $50, or $100) available to them for abstaining from cocaine during two discrete 48-hr periods during the week (Monday through Wednesday; Wednesday through Friday). Observed urine specimens were collected and tested on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday and assessed for recent drug use versus abstinence (described below). The first incentive (voucher or check) was delivered on Thursday for evidence of abstinence from Monday through Wednesday, and an additional incentive of the same type and amount was provided on Saturday for evidence of abstinence from Wednesday through Friday. The 24-hr delay in providing abstinence feedback was necessary owing to the time required to conduct quantitative urine testing (described below).

Figure 1.

Timeline of methods during cocaine abstinence test conditions.

Voucher incentives were provided as slips of paper that indicated the amount earned for the completed abstinence period as well as the cumulative voucher earnings available to the participant. Voucher earnings could be redeemed at any time during weekday clinic visits. Participants would complete a purchase order with their counselor, which indicated the items or services they wished to purchase. Goods were delivered to the participants within 2 weekdays of this request. The goods and services obtained with the vouchers varied considerably across participants, but most were redeemed for clothing, food items, transportation, and personal hygiene/grooming or to cover the cost of home utilities. Checks were selected as the cash-based incentive because of the limited security resources at the clinic during the study. For participants who did not have a personal bank account, checks could be cashed free of charge at a local bank located approximately two blocks from the research clinic.

Abstinence Criteria

Cocaine abstinence was assessed via quantitative urine benzoylecgonine testing on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday during experimental conditions and washout weeks. Urine samples were collected under observation of a same-sex research assistant and temperature tested to confirm their validity. Cocaine metabolite quantitation was conducted using an enzyme-multiplied immunoassay technique on a Syva 30R instrument (Dade-Behring, Cupertino, CA). Serial dilutions were performed when necessary until values fell within the quantitative range deemed valid by the instrument manufacturer (300–3,000 ng/ml). Participants were considered abstinent during the first 48-hr abstinence test if the urine sample provided on Wednesday either was cocaine negative (<300 ng/ml benzoylecgonine) or showed a 50% or greater reduction in benzoylecgonine concentration compared with the sample provided on Monday (Preston, Silverman, Schuster, & Cone, 1997). Similarly, they were considered abstinent if the Friday urine sample was cocaine negative or had at least 50% lower benzoylecgonine concentration compared with the sample obtained on Wednesday. Missing samples were considered positive.

Analyses

The aims of the study were twofold: (a) to assess the efficacy of voucher versus check incentives in initiating short periods of cocaine abstinence and (b) to assess the safety of providing high-magnitude cash-based incentives (checks) to cocaine-abusing drug treatment patients. To address this first aim, we used a repeated measures analysis of variance (PROC MIXED procedure with autoregressive[1] covariance structure in SAS 9.1) to investigate differences in abstinence rates with respect to the incentive type (voucher vs. check) and incentive value during the BAT conditions. The GLIMMIX macro was used for this analysis because the $100 voucher condition was missing for 1 participant owing to incarceration that occurred during the final study condition. Planned comparisons using independent-samples t tests were conducted to detect magnitude differences ($0 vs. $25, $0 vs. $50, and $0 vs. $100) within each incentive type and to detect effects of incentive type at each magnitude within the model. We hypothesized that greater abstinence rates would be observed during “active” experimental conditions ($25, $50, and $100) compared with control conditions ($0) and when checks could be earned compared with vouchers. Because several nonsignificant trends were observed in the initial analysis, a secondary analysis using the same model was conducted with the four experimental conditions collapsed into low ($0/$25) and high ($50/$100) magnitude conditions to increase statistical power.

To assess the safety of providing cash-based incentives, we compared cocaine use following receipt of the highest magnitude (greatest risk) check condition with cocaine use following the control ($0) condition for the 11 participants who earned at least $100 (of $200 possible) during the $100 check condition. Urinalysis results for these individuals were compared using a z test for dependent proportions. This allowed for the detection of carryover effects of receiving high-magnitude cash-based incentives on cocaine use when abstinence incentives are removed. Abstinence during the washout periods was determined in the same manner as during the experimental conditions, and data are presented as the percentage of Wednesday and Friday washout period samples indicating abstinence since the prior urine test.

Results

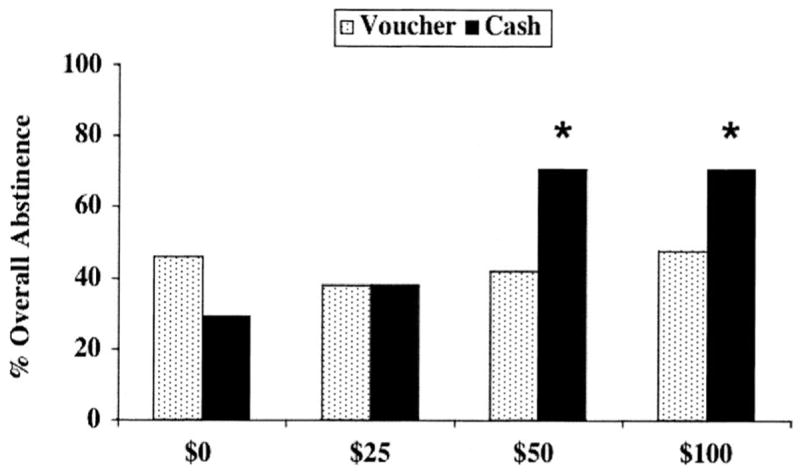

Rates of cocaine abstinence detected during all earning opportunities are illustrated in Figure 2. No main effect of incentive type or magnitude was observed in the initial data analysis. However, planned comparisons indicated significantly higher abstinence rates during the $50 check (71%) and the $100 check (71%) conditions relative to the control condition (29%), t(1) = −2.4, p ≤.05, for both comparisons. Further, there were nonsignificant trends toward greater abstinence in the $50 and $100 check conditions (71% in each) compared with the same high-magnitude voucher conditions (42% and 48% abstinence in the $50 and $100 conditions, respectively). The secondary analysis that collapsed low ($0/$25) and high ($50/$100) magnitude conditions yielded a significant interaction of incentive type and magnitude, F(1, 11) = 4.64, p ≤ .05. Further, a planned comparison of incentive type indicated that more cocaine abstinence was detected during high-magnitude check conditions compared with high-magnitude voucher conditions, t(1) = 2.16, p ≤ .05.

Figure 2.

Percentage of occasions when cocaine abstinence was detected either from Monday through Wednesday or from Wednesday through Friday on the basis of quantitative urinalysis criteria. Data in each bar are based on 24 abstinence opportunities (2 opportunities per condition × 12 participants). Asterisks indicate significant differences from the control ($0) condition.

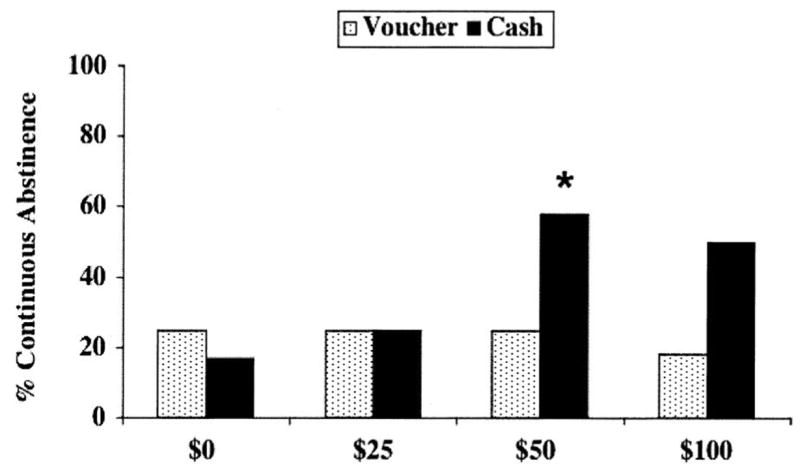

Percentage of participants who were continuously cocaine abstinent (from Monday to Friday) during the experimental conditions is shown in Figure 3. No main effect of incentive type or magnitude was observed on continuous cocaine abstinence in the initial data analysis. Planned comparisons indicated significantly more continuous abstinence during the $50 check condition (58% of participants continuously abstinent) compared with control (17% abstinent), t(1) = −2.1, p ≤ .05. Trends were also observed for greater rates of continuous abstinence in the $100 check condition compared with control and for the $50 and $100 check conditions (58% and 50% of participants continuously abstinent) compared with the $50 and $100 voucher conditions (25% and 18% abstinent). In the secondary analysis, the interaction of incentive type and magnitude approached significance, F(1, 11) = 3.52, p = .08, and planned comparisons indicated that greater rates of continuous abstinence were achieved during high-magnitude check conditions compared with low-magnitude check conditions, t(1) = 2.52, p ≤.05, and during high-magnitude check conditions compared with high-magnitude voucher conditions, t(1) = 2.35, p ≤.05.

Figure 3.

Percentage of participants (N = 12) with evidence of continuous abstinence from Monday through Friday by abstinence condition. Asterisk indicates a significant difference from the control ($0) condition.

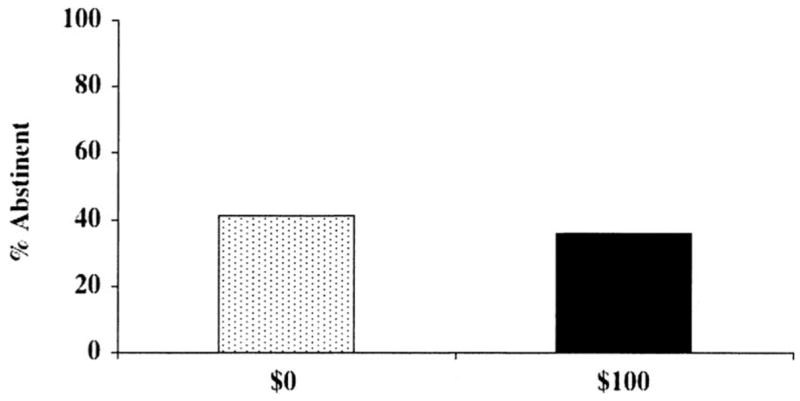

When the $100 check was available as an incentive, 5 participants abstained either from Monday to Wednesday or from Wednesday to Friday, earning $100; 6 participants abstained the entire week, earning $200; and 1 participant did not abstain at all. Cocaine abstinence rates during the washout periods following the $100 and $0 check conditions for the 11 participants who earned at least $100 are shown in Figure 4. No difference in abstinence was observed (z = 0.30, p > .65).

Figure 4.

Percentage of occasions when abstinence was detected either from Monday through Wednesday or from Wednesday through Friday of the washout week on the basis of quantitative urinalysis criteria. Data are shown only for washout weeks following $0 and $100 cash payments and include 11 (of 12) participants who earned at least one incentive during the $100 cash payment condition.

Discussion

The current study extends prior clinical and experimental research suggesting that the type and magnitude of incentives are important variables in determining the outcome when contingent reinforcement is used to modify drug use behavior. Greater rates of cocaine abstinence were attained when high-magnitude ($50 or $100) cash-based incentives (checks) could be earned for abstinence compared with control (no-incentive) conditions or when goods-based incentives (vouchers) of equal value were available. This finding is consistent with prior laboratory studies demonstrating that drug abusers value cash-based incentives over voucher alternatives (Hart et al., 2000; Rosado et al., 2005). This is important from both clinical and budgetary perspectives, because not only are cash-based incentives associated with greater abstinence rates, but they also require minimal overhead cost compared with voucher or prize-based incentives.

The safety of using cash-based incentives as part of drug abuse treatment interventions is supported in this study in that receipt of high-magnitude check payments did not result in increased rates of subsequent cocaine use relative to other incentive and no-incentive conditions. Continuous abstinence was greatest during the $50 and $100 check conditions despite receipt of a check in the middle of the abstinence test period. Furthermore, abstinence rates (as detected by quantitative urinalysis testing) during washout periods following receipt of at least $100 in checks were not different from abstinence rates during washout periods following control (no-incentive) conditions within participants.

These safety data are consistent with those of Festinger and colleagues (2005), who randomly assigned drug treatment patients to receive cash or gift certificate payments worth $10, $40, or $100 for completing a 6-month follow-up assessment. Participants offered cash were significantly more likely to complete the follow-up visit compared with those offered gift certificates (48% vs. 37%; odds ratio = 1.97). Further, a safety assessment conducted 1 week after receipt of the incentives indicated that rates of new drug use were low and did not differ by incentive type (7–14% for cash, 8–25% for gift certificates). Contrary to the concern that cash-based incentives could precipitate drug use among substance abusers, these data provide initial empirical support for cash-based incentives as a safe incentive alternative.

Although the current study adds to support for the safety and efficacy of cash-based incentives, additional research will be needed to address the limitations of the current study and other general concerns before the use of cash-based incentives can be adopted in clinical practice. With regard to limitations of the current study, the sample size was small, and as a result, secondary analyses using collapsed conditions were needed to obtain statistical significance for the differences observed between the voucher and check conditions. Second, we provided incentives in the form of personal checks, which may not be equivalent to actual paper money. The better outcomes seen under the check payment condition are especially notable given this delay in actual cash delivery. Nevertheless, replication of these findings using actual cash-in-hand rewards would be useful. Third, an incentive magnitude effect was seen for the check but not for the voucher conditions, which is inconsistent with previous research that has shown a magnitude effect with vouchers (Dallery et al., 2001; Silverman et al., 1999). It is unclear why no voucher magnitude effect was seen in the current study. It may be due to the sample size, the context in which cash-based incentives were also available, or some other aspect of the study design. Last, because the BAT model excludes many elements of contingency management as it is used in applied settings (escalating incentives for continuous abstinence, reset contingencies, etc.), these findings need to be replicated in clinical trials.

Beyond assessments of efficacy and patient safety, several other concerns regarding the use of cash-based incentives warrant discussion. Although actual cash incentives are immediate and powerful reinforcers, careful consideration would be needed to address the security concerns associated with the transfer and storage of money in clinics. Security concerns can be minimized with the use of checks; however, a substantial portion of substance abusers may lack a bank account or other resources with which they can cash checks without penalty. Clinics could attempt to arrange patient check cashing with their local banking affiliate, but this may not always be possible.

Another potential limitation of cash-based incentives is the reduced control for clinicians to ensure that patients use their abstinence incentives to purchase goods or services that can promote a long-term drug-free lifestyle change. For example, in the voucher incentive system developed by Higgins and colleagues, clinicians target specific activities for voucher redemption that are attractive to the patient but are also intended to compete with drug use. Although the role of specific voucher purchases has not been investigated, the overall efficacy of the voucher incentive method has been amply demonstrated for improving long-term treatment retention and outcomes of drug abuse patients (Higgins et al., 1994, 2000), and the use of vouchers to support lifestyle enhancements may be an important element contributing to this effectiveness. Though clinicians can recommend similar purchases to patients using a cash-based system, patient compliance and ultimate long-term outcomes will need to be studied.

Last, it is possible that members of the public will have a more negative perception about providing cash-based incentives compared with prizes or voucher-based incentives to substance abusers for achieving treatment goals (Kirby et al., 2006). However, continued exposure to the concept and accumulation of empirical evidence that clearly indicates the clinical utility and cost effectiveness of contingency management interventions (cash based or goods based) may ultimately change these attitudes.

In sum, the present study contributes initial support for the safety and efficacy of cash-based incentives when they are used to promote abstinence in drug abuse treatment patients. These findings suggest further research on the use of cash-based incentives in clinical applications of contingency management is warranted. Clinical trials using larger samples and more prolonged exposure to cash-based incentives would be especially useful. With regard to safety, future studies should consider including a therapy component on money management when cash-based incentives are offered as incentives and assessing the uses for which patients spend their earned cash incentives. Research on the optimal circumstances for use of cash-based versus voucher or prize incentives is also needed. For example, one approach could be to use voucher incentives early in treatment, when patients are more vulnerable to relapse, thereby limiting safety concerns, and then transition to use of cash-based incentives after a period of sustained abstinence is achieved. Alternatively, the more potent cash incentives may be useful for promoting initial abstinence in some patients, with a subsequent switch to vouchers. Future research can help clarify the optimal use of cash-based incentives and can address any lingering clinical and community concerns surrounding such an approach.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grants R01–DA12439 and T32–DA07209. We thank Linda Felch, Lindsay Ward, and the staff of the Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit methadone clinic for assistance conducting the study and preparing the manuscript for publication.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Sigmon SC, Higgins ST. Contingency management: Using science to motivate change. In: Coombs RH, editor. Addiction recovery tools: A practical handbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. pp. 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Silverman K, Chutuape MA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Voucher-based reinforcement of opiate plus cocaine abstinence in treatment-resistant methadone patients: Effects of reinforcer magnitude. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9:317–325. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drebing CE, Van Ormer A, Krebs C. The impact of enhanced incentives on vocational rehabilitation outcomes for dually diagnosed veterans. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:359–372. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.100-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger DS, Marlowe DB, Croft JR, Dugosh KL, Mastro NK, Lee PA, et al. Do research payments precipitate drug use or coerce participation? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;78:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Haney M, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Alternative reinforcers differentially modify cocaine self-administration by humans. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2000;11:87–91. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200002000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Alessi SM, Dantona RL. Voucher-based incentives: A substance abuse treatment innovation. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:887–910. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Foerg F, Donham R, Badger G. Incentives improve outcome in out-patient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:568–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070060011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Foerg F, Badger G. Achieving cocaine abstinence with a behavioral approach. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:763–769. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Wong CJ, Badger GJ, Ogden DH, Dantona R. Contingent reinforcement increases cocaine abstinence during outpatient treatment and 1 year of follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:64–72. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KC, Benishek LA, Dugosh KL, Kerwin ME. Substance abuse treatment providers’ beliefs and objections regarding contingency management: Implications for dissemination. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;85:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Marx J, Austin M, Tardif M. Vouchers versus prizes: Contingency management treatment of substance abusers in community settings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:1005–1014. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B. Low-cost contingency management for treating cocaine- and opioid-abusing methadone patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:398–405. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, Kranzler HR. Give them prizes, and they will come: Contingency management for treatment of alcohol dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:250–257. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Silverman K, Schuster CR, Cone EJ. Assessment of cocaine use with quantitative urinalysis and estimation of new uses. Addiction. 1997;92:717–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles E, Silverman K, Preston KL, Cone EJ, Katz E, Bigelow GE, et al. The brief abstinence test: Voucher-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:205–212. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado J, Sigmon SC, Jones HE, Stitzer ML. Cash value of voucher reinforcers in pregnant drug-dependent women. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;13:41–47. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.13.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman KS, Chutuape MAD, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Voucher-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in treatment-resistant methadone patients: Effects of reinforcement magnitude. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:128–138. doi: 10.1007/s002130051098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]