Abstract

Infection with human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) is strongly associated with a number of disease states, of which cervical and anal cancers represent the most drastic endpoints. Induction of T-cell-mediated immunity, particularly cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), is important in eradication of HPV-induced lesions. Studies have shown that heat shock protein fusion proteins are capable of inducing potent antigen-specific CTL activity in experimental animal models. In addition, E7-expressing tumors in C57BL/6 mice can be eradicated by treatment with HspE7, an Hsp fusion protein composed of Mycobacterium bovis BCG Hsp65 linked to E7 protein of HPV16. More importantly, HspE7 has also displayed significant clinical benefit in phase II clinical trials for the immunotherapy of HPV-related diseases. To delineate the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of HspE7, we investigated the capability of HspE7 to induce antigen-specific protective immunity. Here, we demonstrate that HspE7 primes potent E7-specific CD8+ T cells with cytolytic and cytokine secretion activities. These CD8+ T cells can differentiate into memory T cells with effector functions in the absence of CD4+ T-cell help. The HspE7-induced memory CD8+ T cells persist for at least 17 weeks and confer protection against E7-positive murine tumor cell challenge. These results indicate that HspE7 is a promising immunotherapeutic agent for treating HPV-related disease. Moreover, the ability of HspE7 to induce memory CD8+ T cells in the absence of CD4+ help indicates that HspE7 fusion protein may have activity in individuals with compromised CD4+ functions, such as those with invasive cancer and/or human immunodeficiency virus infection.

Human papillomaviruses (HPV) have been detected in most anogenital cancers, and HPV type 16 (HPV16) is closely associated with severe cervical dysplasia and with cervical, anal, and approximately 25% of head and neck cancers (12, 15, 25, 51). Evidence indicates that proper immunosurveillance can impede HPV-associated tumor development and that T-cell immunity is important in the resolution and control of HPV-induced diseases (15, 25, 45, 50). Cellular immune responses to HPV-E6 and/or E7 oncoproteins are detectable in some patients diagnosed with HPV-associated malignancies. However, these responses are not strong enough to inhibit cancer development (28, 30, 37, 41, 42). Many experimental therapeutic approaches for enhancing the preexisting immunity have been examined, including treatment with synthetic peptides, chimeric virus-like particles, recombinant proteins, plasmid DNA, and viral or bacterial vectors expressing E6 and/or E7-proteins and adoptive transfer of tumor-specific T cells (reviewed in references 14, 15, 25, and 31). Some of these experimental approaches have been evaluated in clinical studies to verify the concept of promoting HPV-specific antitumor immune responses for the treatment of not only precursor lesions but also fully developed cervical cancer (reviewed in references 14 and 31). The observed clinical responses to date, however, were inadequate in these trials. One reason for this inadequacy might be the failure of these therapeutic approaches to induce strong, sustained immunity in cancer patients with impaired immune function. Therefore, ways to develop more potent immunotherapies aimed at initiating very robust anti-HPV immune responses need to be thoroughly explored.

Heat shock proteins (Hsp), besides their well-characterized role as protein chaperones, are highly immunogenic and play a fundamental role in immune surveillance of infection and malignancy (27, 33, 43). The ability of mycobacterial Hsp to elicit antigen-specific immunity has been examined in the context of recombinant fusion proteins (2, 9, 11, 17, 18, 23, 32). Previous studies have shown that a single treatment with HspE7, an Hsp fusion protein composed of Mycobacterium bovis BCG Hsp65 linked to E7 protein of HPV16, can eradicate the outgrowth of established TC-1 tumors (a HPV16 E7-expressing tumor cell line) in C57BL/6 mice (10). Immunization with equimolar doses of E7 protein alone failed to induce tumor regression in this tumor model. By using CD8+ knockout (CD8+-KO) or major histocompatibility complex class II Aβ-chain gene KO (MHC-II KO) mice or depleting CD8+ or CD4+ lymphocyte subsets, Chu and colleagues demonstrated that the TC-1 tumor regression following therapeutic treatment was CD8 dependent and CD4 independent. They also showed that HspE7 immunization induced cytolytic activity against TC-1 tumor cells when the splenocytes were restimulated in vitro with inactivated TC-1 cells (10). Although HspE7 immunization has been demonstrated to induce the regression of established TC-1 tumors through a CD8-dependent mechanism which is likely linked to the generation of E7-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), many parameters of the induction of an E7-specific cellular immune response by HspE7 as well as the question of the optimal immunization regimen have not been explored. It is likely that effective immunotherapy of HPV-induced cancers will require the generation of very strong antitumor immune responses. Thus, the current study was undertaken to further characterize the cellular anti-E7 immune response induced by HspE7 immunization and to determine the optimum immunization regimen for inducing effective antitumor immunity. The study investigated the ability of HspE7 to induce E7-specific memory CD8+ T cells, the optimal regimen for the induction of memory T cells, and the abilities of these memory T cells to protect mice against antigen-positive TC-1 tumor challenge. The results of our studies demonstrate that a prime-boost immunization with an 8-week interval is optimal for inducing anti-E7 immunity and preventing outgrowth of a subsequent tumor challenge. Further, these studies show that immunization of CD4-deficient mice with HspE7 induces potent antigen-specific cytolytic CD8+ T cells that are able to proliferate following a boost immunization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Female C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (St. Constant, QC, Canada). MHC-II KO mice on a C57BL/6 background were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). Mice were housed in filter top cages under specific pathogen-free conditions and were used in accordance with the guidelines of Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC) and the Nventa Animal Care Committee.

Cell lines.

The EL4 thymoma cell line (H-2b) was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). EL4/E7 cells were generated at Nventa Biopharmaceuticals Corporation by transfecting EL4 cells with plasmid DNA encoding the full-length wild-type E7 gene of HPV16. EL4/E7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; HyClone, Logan, UT), 2 mM l-glutamine (GIBCO/BRL, Burlington, ON, Canada), and 1.5 mg/ml Geneticin (GIBCO/BRL). A more tumorigenic subline of TC-1 tumor cells (transduced with the HPV16 E6, E7, and activated human Ha-ras genes) was kindly provided by W. M. Kast (University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA) and maintained as previously described (24).

HspE7 fusion protein and peptide.

HspE7 fusion protein, Hsp65 of M. bovis BCG, and (h)E7 (N terminus histidine-tagged HPV16 E7) were purified as previously described (10). E7.49-57.Db peptide (RAHYNIVTF, amino acids 49 to 57 of the E7 protein) with >95% purity, a defined H-2Db-restricted CTL epitope, was synthesized by AnaSpec Inc. (San Jose, CA). NP.366-374.Db peptide (ASNENMETM, amino acids 366 to 374 from the nucleoprotein of influenza virus) with >95% purity was synthesized by Research Genetics (Huntsville AL).

CTL assay.

Mice (four per group) were immunized by subcutaneous injection of various immunogens at the nape of the neck. In some cases, a boost immunization was given 2 to 8 weeks later as specified for each experiment. Control mice received a sham injection of Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) or histidine buffer (30 mM histidine, 5% trehalose, pH 7.6). In some experiments, molar equivalents of Hsp65, (h)E7, or an admixture of Hsp65 and (h)E7 were used as controls. Mice were euthanized by CO2 or cervical dislocation at the desired time point after immunization. Single-cell suspensions of pooled spleens from each group were prepared in CTL medium: RPMI 1640 (GIBCO/BRL) supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate (GIBCO/BRL), 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 50 μg/ml gentamicin sulfate (GIBCO/BRL). Splenocytes were restimulated in 10 ml CTL medium by incubating 3 × 107 viable lymphoid cells in the presence of 1 μM E7.49-57.Db peptide in an upright T25 tissue culture flask. The effector cells were harvested after 7 days and analyzed for cytolytic activity and intracellular gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production. Cytolytic activity was assayed in triplicates in 96-well culture plates by culturing the effector cells with 51Cr-labeled EL4 target cells pulsed with E7.49-57.Db-peptide or EL4 cells expressing E7 endogenously (EL4/E7 cells) at effector/target (E/T) ratios of 100:1, 33:1, or 11:1. Control targets were 51Cr-labeled EL4 cells pulsed with an irrelevant H-2Db-restricted influenza virus (NP.366-374.Db) peptide. After 4 h of incubation at 37°C/5% CO2, the 96-well culture plates were centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min using a Beckman G5-6R centrifuge (Beckman Coulter Canada, Mississauga, ON). One hundred microliters of the culture supernatant was collected from each well into Beckman ready caps, and the released radioactivity was determined by scintillation counting using a Beckman LS 6500 multipurpose scintillation counter. To determine spontaneous or total release of the label, target cells were cultured without effector cells in either medium or Triton X-100 (1% [wt/vol]), respectively. Results were expressed as percent specific lysis, which was calculated as [(cmptest − cpmspont)/(cpmtotal − cpmspont)] × 100. The control target lysis values were consistently <10% and were subtracted from the results shown.

Intracellular-cytokine assay.

Flow cytometry was performed to detect IFN-γ production by E7-specific CD8 T cells. The restimulated effector cells were harvested after 7 days and incubated with 1 μM E7.49-57.Db peptide for 4 h at 37°C in the presence of GolgiStop (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Cells were harvested and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-CD8α (clone 53-6.7; BD Biosciences) in DPBS containing 0.3% FCS. The cells were fixed and permeabilized using a Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were then stained for intracellular IFN-γ with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2; BD Biosciences) and analyzed by a FACSCalibur flow cytometer using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

ELISA for cytokine detection.

To quantitate the release of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and IFN-γ from E7-specific CD8+ T cells, the restimulated effector cells were seeded in U-bottomed 96-well microtiter plates in triplicates and cocultured with 1 μM E7.49-57.Db peptide and EL4 target cells at E/T ratios of 100:1, 33:1, or 11:1. The culture supernatants were harvested after incubation at 37°C/5% CO2 for 4 h, and the amounts of TNF-α and IFN-γ released were determined using OptEIA mouse TNF-α and IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

IFN-γ ELISPOT.

Multiscreen HTS-IP filtration 96-well plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA) were coated overnight with 0.5 μg per well of purified anti-mouse IFN-γ (monoclonal antibody AN18; MabTech, Cincinnati, OH) in phosphate-buffered saline. The plates were washed and blocked for 2 h with RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS at 37°C/5% CO2. Triplicate cultures of freshly isolated splenocytes were plated at 2 × 106, 1 × 106, and 0.5 × 106 cells per well in CTL medium. Similarly, the splenocytes, after restimulation for 7 days, were plated at 2 × 104, 1 × 104, and 0.5 × 104 cells per well in the presence of 1 × 106 feeder cells. The cells were cultured with 1 μM E7.49-57.Db peptide or medium alone for 18 to 22 h at 37°C/5% CO2. After the plates were washed, the bound IFN-γ was detected with biotinylated anti-mouse IFN-γ (R4-6A2 Biotin; MabTech) followed by streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (MabTech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The spots of IFN-γ-secreting cells were visualized by incubation with nitroblue tetrazolium-BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate) substrate (BioLynx, Brockville, ON, Canada) and enumerated using the Carl Zeiss automated enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT) system. The data for IFN-γ-producing cells are expressed as numbers of spot-forming cells (SFC) per 106 or 104 splenocytes as indicated in the figures.

Bio-Plex cytokine assay.

To assess the cytokine secretion profile of splenocytes from HspE7-immunized mice, pooled splenocytes from groups of four mice were harvested and made into a single-cell suspension. Using 96-well flat-bottomed plates, duplicate cultures of 6× 105 cells were stimulated with medium, 10 μg/ml (h)E7, or 50 μg/ml of HspE7 protein in 0.2 ml for 48 h at 37°C/5% CO2. The production of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IFN-γ, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10 were determined from culture supernatants by using a Bio-Rad custom Bio-Plex cytokine assay kit (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In vivo tumor protection.

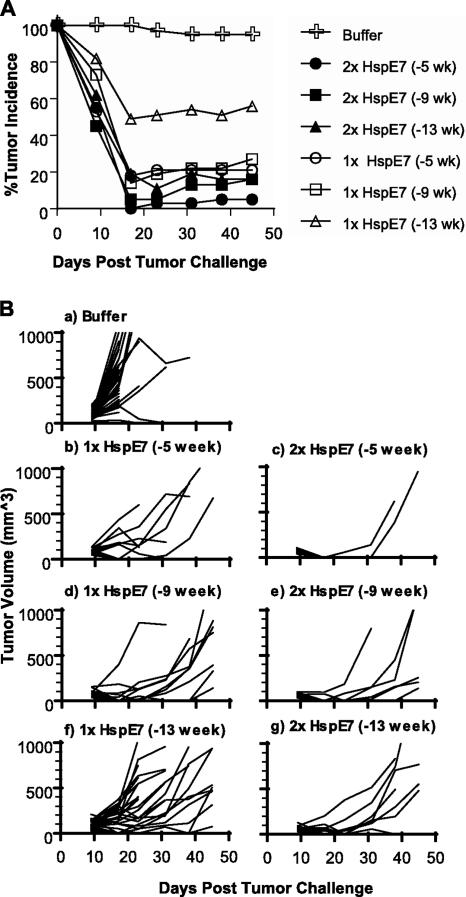

Mice (13/group) were immunized with 400 μg HspE7 once (1× HspE7) or twice with an 8-week interval (2× HspE7). The immunizations were staggered so that tumor challenge occurred on the same day for all groups, either 5, 9, or 13 weeks after the last immunization. The mice were challenged subcutaneously with 6 × 104 TC-1 tumor cells/mouse in the hind flank. Tumor incidence and volume were monitored weekly and recorded beginning 9 days after tumor challenge, and monitoring continued for up to 45 days. If a tumor was detected, the two longest dimensions were measured using an electronic digital caliper (Fowler Sylvac Ultra-Cal Mark III). Tumor volumes were calculated by width2 × length × 0.5 (29). The tumor-bearing mice were euthanized when the tumor volume reached approximately 2,500 mm3 according to the CCAC guideline. Differences in tumor incidence between treatment groups 45 days following tumor challenge were evaluated by Fisher's exact test.

RESULTS

HspE7 primes potent E7-specific CD8+ T-cell responses.

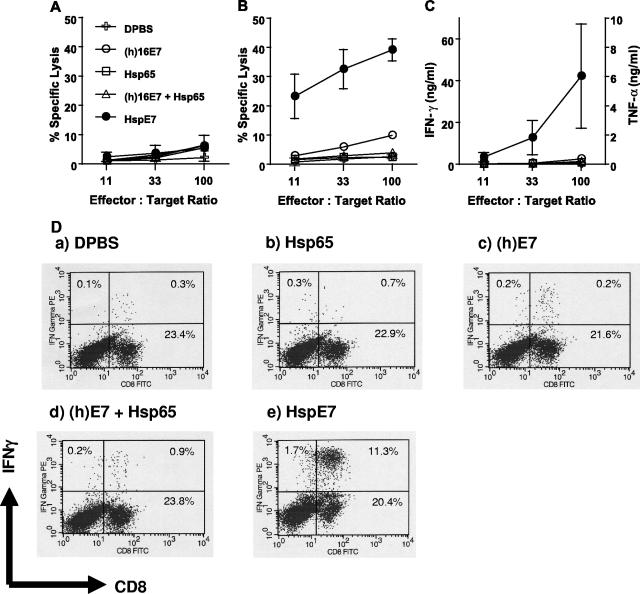

It has been demonstrated previously that HspE7 is able to induce the regression of E7-expressing TC-1 tumors in mice through either prophylactic or therapeutic treatment (10). To examine whether HspE7 is able to prime E7-specific CD8+ T cells, C57BL/6 mice were immunized once subcutaneously with DPBS, 250 μg HspE7, or molar equivalents of Hsp65, (h)E7, or an admixture of Hsp65 and (h)E7. Splenocytes were harvested 7 days after immunization and restimulated in vitro for 7 days with a defined H-2Db-restricted E7 CTL epitope peptide (E7.49-57.Db) (13). The cytolytic activities of the restimulated splenocytes against 51Cr-labeled target cells were assayed. When activity against 51Cr-labeled EL4 cells pulsed with an irrelevant NP.366-374.Db peptide for specificity control was assayed, no E7-specific cytolytic activity was detected (Fig. 1A). When activity against 51Cr-labeled EL4 cells pulsed with E7.49-57.Db peptide was assayed, a single subcutaneous immunization of C57BL/6 mice with HspE7 was found to induce a strong E7-specific cytolytic activity (Fig. 1B). An equivalent result was obtained when EL4/E7 cells expressing E7 endogenously were used as target cells (data not shown). The restimulated splenocytes were also able to lyse 51Cr-labeled TC-1 tumor cells (data not shown). In contrast, the restimulated splenocytes from mice immunized with (h)E7, Hsp65 alone, or an admixture of Hsp65 and (h)E7 exhibited very low to no cytolytic activity (Fig. 1B). These results demonstrate that the covalent linkage between Hsp65 and E7 is necessary for priming potent E7-specific CD8+ T-cell responses.

FIG. 1.

HspE7 fusion protein primes E7-specific CD8+ T-cell responses. C57BL/6 mice (four per group) were immunized once subcutaneously with DPBS, 250 μg HspE7, or molar-equivalents of (h)E7, Hsp65, or an admixture of Hsp65 and (h)E7. At 7 days postimmunization, pooled splenocytes from each group were restimulated with 1 μM E7.49-57.Db peptide for 7 days and assayed for CD8+ responses. E7-specific cytolytic activity against 51Cr-labeled EL4 cells pulsed with an irrelevant NP.366-374.Db peptide as target cells for specificity control (A) or 51Cr-labeled EL4 cells pulsed with E7.49-57.Db peptide (B) was assayed. The same results were obtained when EL4/E7 or TC-1 tumor cells, which express E7 endogenously, were used as target cells. (C) TNF-α and IFN-γ were detected in the supernatant of the same restimulated splenocytes used for panels A and B after exposure to E7.49-57.Db peptide for 4 h. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of IFN-γ expression from the same restimulated splenocytes used in panels A to C. Data shown are means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments.

In addition to the cytolytic activity, we also examined the capability of the restimulated splenocytes to secrete cytokines, such as TNF-α and IFN-γ. As seen in the target cell lysis assay, only cells from HspE7-immunized mice secreted TNF-α and IFN-γ after exposure to E7.49-57.Db peptide for 4 h (Fig. 1C). Similar results were also obtained by intracellular IFN-γ staining (Fig. 1D). The majority of the IFN-γ producing cells were positive for CD8, indicating that the IFN-γ producing cells are E7.49-57.Db-specific CD8+ T cells.

HspE7-induced immune responses are dose dependent and can be boosted.

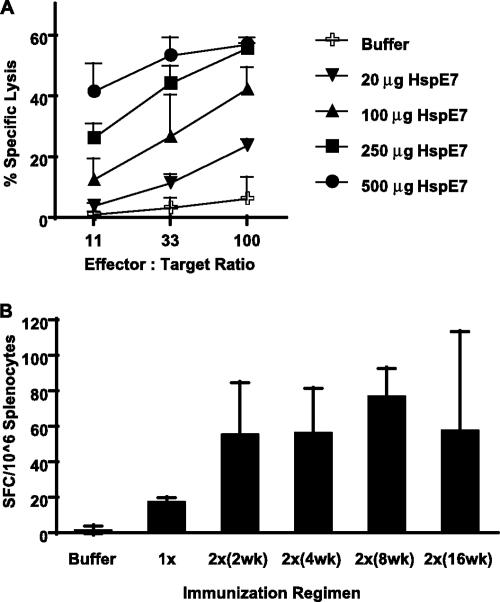

To determine the correlation between antigen dose and CTL activity, C57BL/6 mice were immunized once with 20, 100, 250, or 500 μg of HspE7 fusion protein. The splenocytes were restimulated, and their activities against 51Cr-labeled target cells were assayed. The results show that CTL activity induced by a single HspE7 immunization is dose dependent (Fig. 2A). Twenty micrograms of HspE7 fusion protein was capable of eliciting weak E7-specific CTL activity, and the peak lytic activity of approximately 60% was observed when the doses administered were between 250 and 500 μg HspE7.

FIG. 2.

HspE7 induces dose-dependent CD8+ responses. (A) C57BL/6 mice (four per group) were immunized once with different doses of HspE7. At 7 days postimmunization, pooled splenocytes from each group were restimulated with E7.49-57.Db peptide for 7 days and their specific lytic activities against 51Cr-labeled EL4 cells pulsed with E7.49-57.Db peptide at 11:1, 33:1, and 100:1 E/T ratios were assayed. Similar results were obtained when EL4/E7 cells expressing E7 endogenously were used as target cells. No cytolytic activity against EL4 cells pulsed with an irrelevant NP.366-374.Db peptide was detected with the assay. (B) Four hundred micrograms of HspE7 was given as a single immunization (1×) or a prime-boost immunization with a 2-, 4-, 8-, or 16-week interval (2×). The immunizations were staggered so that the IFN-γ-producing cells were assayed ex vivo by IFN-γ ELISPOT using freshly isolated splenocytes 7 days after the single or the boost immunization. Data shown are means ± standard deviations for two independent experiments.

We also examined the CTL priming activity of 400 μg HspE7 administered as a single dose with that of a prime-boost regimen (two immunizations were given 2, 4, 8, or 16 weeks apart). The immunizations were staggered so that the IFN-γ-secreting cells of all groups were assayed ex vivo at the same time using freshly isolated splenocytes 7 days after the single or the boost immunization. As shown in Fig. 2B, the HspE7-induced immune responses could be boosted and the optimal boosting effect was consistently observed when the two immunizations were given with an 8-week interval.

HspE7 induces CD8+ memory response.

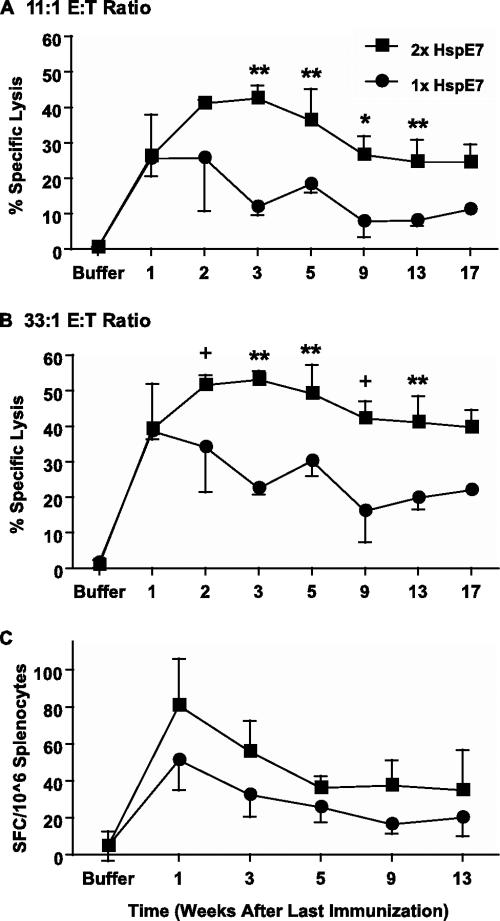

One of the challenges for development of either prophylactic or therapeutic vaccines is to induce potent immune responses and establish long-lasting immune memory. We have demonstrated that HspE7 is able to induce potent E7-specific immune responses (Fig. 1 and 2). To assess whether HspE7 is able to elicit long-lasting memory T cells, mice were immunized once with 400 μg of HspE7. The immunizations were staggered so that the mice were sacrificed and the cytolytic and cytokine-secreting activities of all mice were assayed at the same time. These experiments demonstrated that HspE7 elicited a high level of cytolytic activity in the first week after a single immunization (Fig. 3). The cytolytic activity started to decline at 3 weeks and persisted at approximately one-half of the peak activity until 17 weeks (Fig. 3A and B).

FIG. 3.

HspE7 induces E7-specific CD8+ memory responses. C57BL/6 mice (four per group) were immunized with 400 μg HspE7 once (1×) or twice with an 8-week interval (2×). The immunizations were staggered so that the mice were sacrificed at the same time. Pooled splenocytes from each group were restimulated, and their cytolytic activities against 51Cr-labeled EL4 cells pulsed with E7.49-57.Db peptide were assayed. Similar results were obtained when EL4/E7 were used as target cells. The cytolytic activity was assayed at an 11:1 E/T ratio (A) or a 33:1 E/T ratio (B). No cytolytic activity against EL4 cells pulsed with an irrelevant NP.366-374.Db peptide was detected with the assay. (C) The IFN-γ-producing cells in the pooled splenocytes were assayed ex vivo by IFN-γ ELISPOT. Data shown are means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments. Lytic activities of splenocytes immunized once were compared with those of splenocytes immunized twice by Student's t test. +, P < 0.08; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Of clinical interest, we also examined the prime-boost regimen in CD8+ memory induction. Mice were immunized with 400 μg of HspE7 and the primed T cells allowed to form memory T cells before the response was boosted by a second immunization 8 weeks later. These experiments demonstrated that HspE7 elicited high levels of cytolytic activity at all time points tested when mice were immunized with a prime-boost regimen (Fig. 3A and B). The cytolytic activity peaked at 3 weeks and declined very slowly after the boost immunization compared to what was found for the single immunization (Fig. 3A and B). The peak response was higher and the contraction phase was prolonged after the boost compared to what was found for the single immunization (Fig. 3A and B). We also examined the frequencies of E7-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes at various times following either a single immunization or a prime-boost immunization by ex vivo ELISPOT. Although not significant (P > 0.05), there was a consistent reproducible trend for splenocytes from the prime-boost groups to have higher levels of IFN-γ-secreting cells than splenocytes from the single-immunization groups (Fig. 3C). The memory CD8+ T cells induced by both single-immunization and prime-boost regimens displayed the capability of secreting IFN-γ and TNF-α after restimulation as detected by ELISA and intracellular IFN-γ staining (data not shown).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that (i) HspE7 is able to induce long-lasting memory CD8+ T cells which persist for at least 17 weeks, (ii) these memory CD8+ T cells display functional activities of target cell lysis and cytokine secretion after in vitro restimulation, and (iii) the prime-boost regimen is superior to a single immunization in the induction of memory CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3).

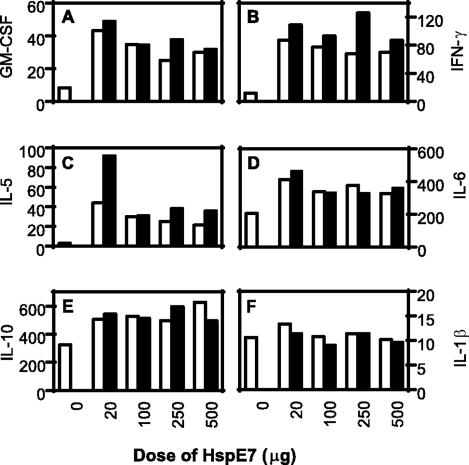

HspE7 immunization induces GM-CSF, IFN-γ, and IL-5 secretion from C57BL/6 mice.

Th1 responses play an important role in protection against pathogen infections and tumor development. Cytokine environment is a major factor in determining the outcome of Th1 versus Th2 responses. We therefore examined the cytokine profiles induced by a single HspE7 immunization or a primary immunization followed by a boost 2 weeks later. The mice were immunized with buffer or different doses of HspE7, and the splenocytes were isolated 7 days after the second immunization and restimulated in vitro with medium, 10 μg/ml (h)E7, or 50 μg/ml of HspE7 fusion protein for 48 h at 37°C/5% CO2. The cytokine profiles were determined from duplicate culture supernatants by a Bio-Plex cytokine assay. The results showed that the splenocytes from mice immunized with HspE7 secreted much more GM-CSF, IFN-γ, and IL-5 than those from mice immunized with buffer upon restimulation with HspE7 fusion protein (Fig. 4A to C). The splenocytes from mice immunized with low doses (20 μg per mouse) of HspE7, especially after prime-boost immunizations, secreted much higher levels of IL-5 than those from mice immunized with higher doses of HspE7 (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that low doses of HspE7 may favor a Th2-like response, while higher doses of HspE7 may drive the immune responses toward a Th1-like profile characterized by the higher ratio of IFN-γ to IL-5 (Fig. 4B and C). HspE7 may also stimulate cytokine production from cells of the innate immune system as splenocytes restimulated in vitro with HspE7 produced IL-1, IL-6, and IL-10 at levels much greater than those seen with splenocytes incubated in medium only. The secretion levels of these cytokines were similar in all splenocytes regardless of whether the mice had been previously immunized with HspE7 or buffer, indicating that the cytokines may be derived from cells of the innate immune system, such as dendritic cells (DCs) (Fig. 4D, E, and F). When splenocytes were stimulated in vitro with medium or (h)E7 protein, background levels of these cytokines which did not exceed 2 pg/ml for GM-CSF and IL-1 or 10 pg/ml for all other cytokines for any group were detected (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

HspE7 immunization induces cytokine secretion. C57BL/6 mice (four per group) were immunized either once (□) with different doses of HspE7 or twice (▪) with a 2-week interval. The splenocytes were isolated 7 days after the second immunization and restimulated in vitro with 50 μg/ml HspE7 fusion protein in duplicate culture wells for 48 h. The cytokine secretions (pg/ml) were determined from the culture supernatants by a Bio-Plex cytokine assay. When splenocytes were stimulated in vitro with medium, background levels of these cytokines which did not exceed 2 pg/ml for GM-CSF and IL-1 or 10 pg/ml for all other cytokines for any group were detected. Data (means for the duplicates) are representative of two independent experiments.

Taken together, these results indicate that HspE7 has the ability to stimulate innate immune cells to secrete proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1 and IL-6. HspE7 is also able to stimulate the antigen-specific immune cells to secrete immune-stimulatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ and CM-CSF. These, in turn, may contribute to a local microenvironment conducive to cell-mediated immunity.

HspE7 primes CD4-independent CD8+ T-cell responses.

We have demonstrated that HspE7 is able to induce potent CD8+ CTL responses in wild-type C57BL/6 mice. To determine the requirement for CD4+ T cells in the induction of CD8+ responses by HspE7, wild-type C57BL/6 and MHC-II KO mice were immunized once with 400 μg HspE7. At 7 days postimmunization, the splenocytes were restimulated with E7.49-57.Db peptide and the cytolytic activity was determined. The results demonstrated that E7-specific CD8+ responses were elicited by HspE7 immunization in the MHC-II KO mice (Fig. 5A). Although not reaching the optimal response seen in the wild-type mice, the CD8+ T cells induced in the MHC-II KO mice were able to lyse both peptide-pulsed target cells and cells expressing E7 endogenously. These CD8+ T cells generated in the absence of CD4+ help were capable of secreting IFN-γ and TNF-α after in vitro peptide restimulation (data not shown). These results demonstrate that class II-restricted CD4+ T cells are not required for either priming or the effector functions of the HspE7-induced CD8+ T cells. However, since the optimal CD8+ responses were detected in the wild-type mice, these results also imply that HspE7 does induce CD4+ T cells which enhance the antigen-specific CD8+ responses in normal individuals. It is likely that immunization with HspE7 induces tumor regression in CD4-depleted and MHC-II KO mice, as we reported previously (10), due to the fact that the cytotoxic T-cell response produced by HspE7 immunization in these mice, although suboptimal, is still of sufficient magnitude to eradicate the growing tumor.

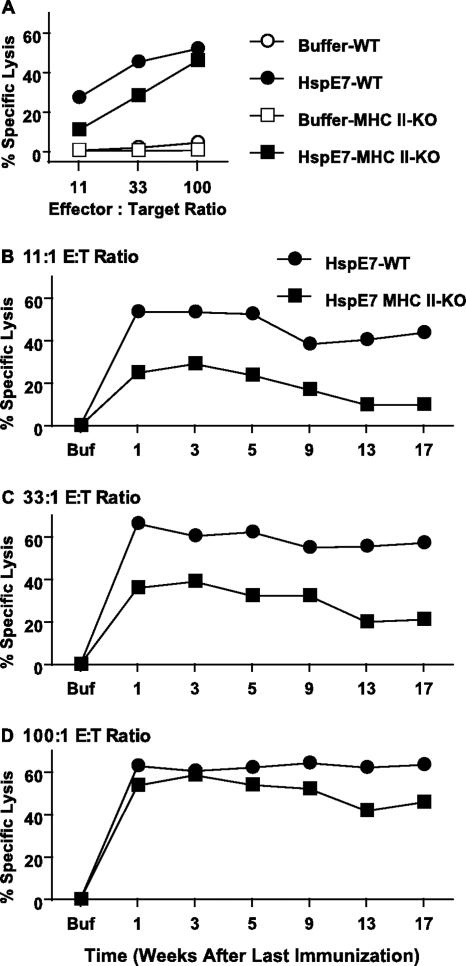

FIG. 5.

HspE7 induces CD4-independent CD8+ memory responses. (A) Wild-type C57BL/6 (WT) and MHC-II KO mice (four per group) were immunized once with either buffer or 400 μg HspE7. Seven days after immunization, pooled splenocytes from each group were restimulated and their activities against 51Cr-labeled EL4/E7 cells were assayed. (B to D) Wild-type C57BL/6 and MHC-II KO mice were immunized twice with 400 μg HspE7 with an 8-week interval. The immunizations were staggered so that the mice were sacrificed at the same time. Pooled splenocytes were restimulated, and their cytolytic activities against 51Cr-labeled EL4/E7 cells at 11:1 (B), 33:1 (C), and 100:1 (D) E/T ratios were assayed. Similar results were obtained when EL4 cells pulsed with E7.49-57.Db peptide were used as target cells. No cytolytic activity against EL4 cells pulsed with an irrelevant NP.366-374.Db peptide was detected with the assay. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

HspE7 induces CD4-independent CD8+ memory response.

To address the role of CD4+ T cells in the induction and maintenance of memory CD8+ T cells, experiments identical to memory induction with the prime-boost regimen as shown in Fig. 3 were performed with both wild-type and MHC-II KO mice. As seen in Fig. 5D, HspE7 induced similar high levels of cytolytic activity in both types of mice at 100:1 E/T ratios; however, the cytolytic activity titrated down faster in MHC-II KO mice than in wild-type mice at 11:1 and 33:1 E/T ratios (Fig. 5B and C). The fast titration of cytolytic activity is most likely due to the fact that fewer E7-specific CD8+ precursors were primed in the MHC-II KO than in wild-type mice as detected ex vivo by IFN-γ ELISPOT (Fig. 6A). The difference in CD8+ T-cell numbers was maintained during the 7-day in vitro restimulation (Fig. 6B). To examine the in vitro proliferative function of the CD4-independent memory CD8+ T cells, the proliferative responses of these CD8+ precursors were determined by their abilities to expand after a reencounter with peptide antigen, which is calculated as the ratio of E7-specific CD8+ T cells detected after a 7-day period of in vitro restimulation to those estimated ex vivo using an IFN-γ ELISPOT. The results showed that the magnitudes of proliferation of memory CD8+ T cells are similar in both types of mice (Fig. 6C), even though the absolute numbers of IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells are much lower in MHC-II KO mice (Fig. 6A and B). In addition to the normal in vitro proliferative response, these CD4-independent memory CD8+ T cells are also capable of secreting TNF-α and IFN-γ after in vitro restimulation (Fig. 6D and E). However, the levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ secreted from the splenocytes of MHC-II KO mice were much lower than those for wild-type mice. TNF-α secretion seemed to be much more dependent on help from CD4+ cells than did IFN-γ secretion (Fig. 6D and E). The low levels of cytokine secretion are most likely due to fewer E7-specific CD8+ T cells secreting these cytokines in MHC-II KO mice than in wild-type mice (Fig. 6B).

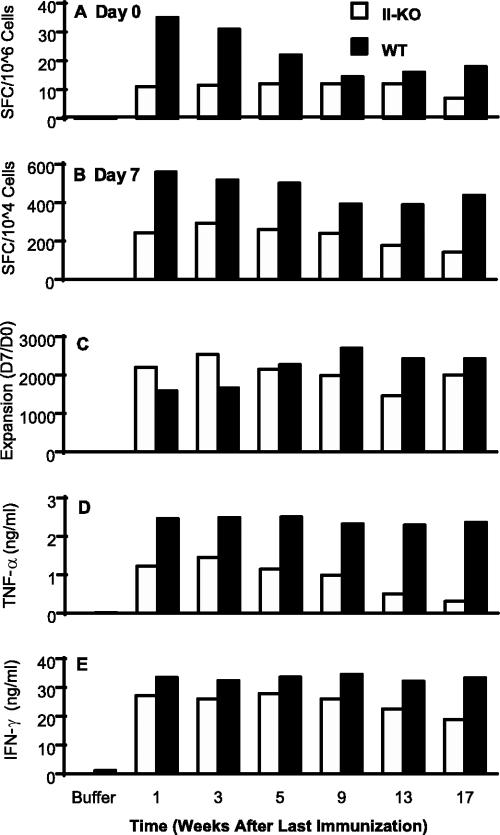

FIG. 6.

HspE7-induced CD4-independent memory CD8+ T cells are able to proliferate and secrete effector cytokines. (A) Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 and MHC-II KO (II-KO) mice (four per group) were immunized twice with 400 μg HspE7 with an 8-week interval. The immunizations were staggered so that the mice were sacrificed at the same time. Pooled splenocytes from wild-type C57BL/6 and MHC-II KO mice were assayed directly ex vivo by IFN-γ ELISPOT in the presence of E7.49-57.Db peptide for the estimation of E7-specific CD8+ T-cell precursors (day 0). (B) The number of E7-specific CD8+ T cells was assayed again after a 7-day restimulation with E7.49-57.Db peptide (day 7). (C) The expansion of the IFN-γ-secreting cells during the 7-day in vitro restimulation was calculated as the ratio of day 7 IFN-γ SFC to day 0 SFC. Levels of TNF-α (D) and IFN-γ (E) secretion from the supernatant of restimulated splenocytes were measured by ELISA. Data (means for triplicate tissue culture wells) are representative of two independent experiments.

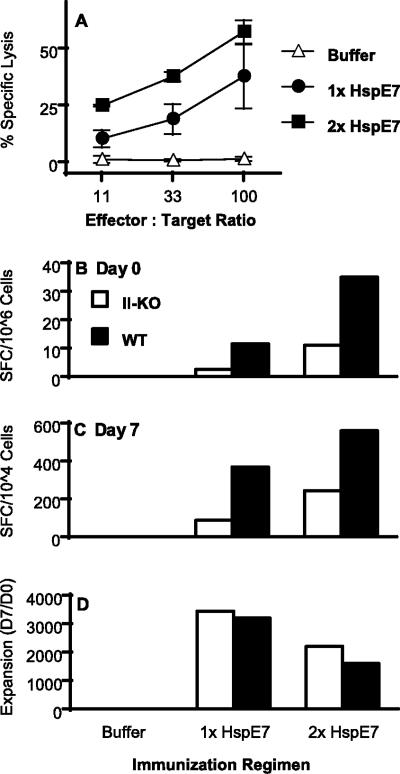

CD4-independent memory CD8+ T cells maintain the ability to undergo boosting upon a reencounter with antigen.

Recent studies have shown that CD8+ memory can be generated without the help of CD4+ T cells during microbial infections but that the proliferative and effector functions of these memory CD8+ T cells are severely impaired during a reencounter with antigens (6, 7, 8, 19, 34, 35, 39). If the proliferative and effector functions of the CD4-independent memory CD8+ T cells induced by HspE7 are impaired during a secondary encounter with antigen, boosting effects on cytolytic and cytokine-secreting activities will not be detectable. To understand the influence of CD4+ T cells on the function of memory T cells induced by HspE7, the proliferative and effector functions of the memory CD8+ T cells were examined in both wild-type and MHC-II KO mice. Mice were immunized with a single HspE7 immunization or two HspE7 immunizations with an 8-week interval. One week after the second immunization, the splenocytes were restimulated and the boosting effects on the cytolytic and cytokine-secreting functions were assessed. The in vivo proliferative response of the memory CD8+ T cells was determined by examining the CD8+ precursor frequency after prime-boost immunization, and the result was compared to that for a single immunization with an ex vivo IFN-γ ELISPOT. In MHC-II KO mice, two HspE7 immunizations induced much higher cytolytic activity than a single immunization (Fig. 7A). Similar results were detected in cytokine (TNF-α and IFN-γ) secretions (data not shown). The boosting effect was also detected in the number of CD8+ T cells capable of secreting IFN-γ ex vivo (day 0) after secondary immunization in both wild-type and MHC-II KO mice (Fig. 7B). These results indicate that repeated HspE7 immunizations stimulate the in vivo proliferation of memory CD8+ T cells with effector functions in the absence of CD4+ help. These CD8+ T cells are also able to proliferate in vitro after an encounter with peptide antigen for 7 days (Fig. 7C). Although fewer E7-specific CD8+ T cells were primed in the absence of CD4+ helper T cells, the magnitudes of in vitro expansion of these CD8+ T cells are same as those detected in the wild-type mice (Fig. 7D).

FIG. 7.

HspE7-induced CD4-independent CD8+ responses can be boosted. (A) MHC-II KO mice (four per group) were immunized once with 400 μg HspE7 or twice with an 8-week interval. One week after the second immunization, pooled splenocytes were restimulated and the boosting effects on cytolytic activity against 51Cr-labeled EL4/E7 cells were determined. No cytolytic activity against EL4 cells pulsed with an irrelevant NP.366-374.Db peptide was detected with the assay. The data shown are means ± standard deviations for two independent experiments. (B) Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 and MHC-II KO (II-KO) mice were immunized either once or twice with 400 μg HspE7 with an 8-week interval. One week after the second immunization, pooled splenocytes were assayed ex vivo (day 0) by IFN-γ ELISPOT for the estimation of E7-specific CD8+ T-cell precursors. (C) The number of E7-specific CD8+ T cells was assayed again after a 7-day restimulation with E7.49-57.Db peptide (day 7). (D) The expansion of the IFN-γ-secreting cells during the 7-day in vitro restimulation was calculated as the ratio of day 7 IFN-γ SFC to day 0 SFC. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that the proliferative and effector functions of the CD4-independent CD8+ and memory CD8+ T cells induced by HspE7 are not impaired upon a reencounter with antigens (Fig. 6 and 7).

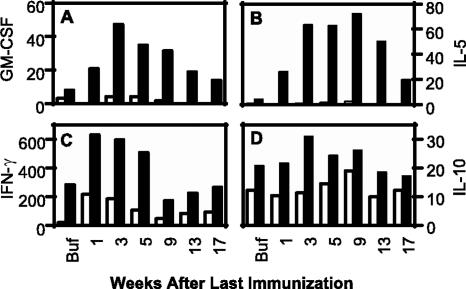

HspE7 induces GM-CSF and IL-5 secretion from wild-type but not from MHC-II KO mice.

To determine the contribution of CD4+ T cells to cytokine secretion profiles, freshly isolated splenocytes of both wild-type and MHC-II KO mice from the memory study were restimulated with medium or 50 μg/ml of HspE7 fusion protein for 48 h, and the cytokine profiles were determined by a Bio-Plex cytokine assay. The results show that the HspE7-stimulated splenocytes from wild-type mice immunized with HspE7 secreted GM-CSF and IL-5, while very little to no GM-CSF and IL-5 were detected from the splenocytes of MHC-II KO mice (Fig. 8A and B). These results imply that GM-CSF and IL-5 were secreted by antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. Consistent with the finding that fewer E7-specific CD8+ T cells were primed in the absence of CD4+ help, lower levels of IFN-γ were detected from the splenocytes of MHC-II KO mice immunized with HspE7 than from the splenocytes of wild-type mice (Fig. 8C). Splenocytes from wild-type mice secreted slightly more IL-10 than splenocytes from MHC-II KO mice; however, the levels of IL-10 secretion were similar between the splenocytes immunized with HspE7 and buffer (Fig. 8D). No differences in IL-1β and IL-6 secretions were detected between the splenocytes from either type of mice immunized with HspE7 when the splenocytes were restimulated with HspE7 (data not shown). As expected, none of these cytokines were observed from the splenocytes of either type of mice immunized with either buffer or HspE7 when the splenocytes were stimulated with medium (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

HspE7-induced memory T cells are capable of secreting cytokines. Pooled splenocytes from wild-type (▪) and MHC-II KO (□) mice were stimulated with 50 μg/ml HspE7 fusion protein in CTL medium for 48 h at 37°C/5% CO2. The production of different cytokines (pg/ml) was determined from duplicate culture supernatants by a Bio-Plex assay. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

HspE7-induced memory CD8+ T cells can protect mice against tumor challenge.

It has been shown previously that the outgrowth of established TC-1 tumors in C57BL/6 mice can be eradicated by treatment with a single HspE7 immunization (10). However, in clinical settings, multiple boosts usually need to be given to patients with cancerous lesions in order to obtain effective cellular immune responses. We have demonstrated that both one and two HspE7 immunizations are able to induce long-lasting memory CD8+ T cells. In order to assess whether a prime-boost regimen is more effective than a single HspE7 immunization in protecting mice from tumor challenge, mice were given either a single immunization with 400 μg HspE7 (1× HspE7) or a prime-boost immunization with an 8-week interval (2× HspE7). The immunizations were staggered so that tumor challenge occurred on the same day for all groups, either 5, 9, or 13 weeks after the second immunization. The mice were 27 weeks old when challenged subcutaneously with TC-1 tumor cells. Histidine buffer was used as a control. The percent tumor incidences and individual mouse tumor volumes from the combined results for three independent experiments are shown in Fig. 9. Tumor incidence in the buffer control group was 100% 9 days after tumor challenge and persisted at 95% thereafter (Fig. 9A and B, panel “a”). The majority of the mice who developed tumors in the control group had to be euthanized approximately 3 weeks after tumor challenge due to the tumor burden. All groups immunized with HspE7 displayed significantly improved protection from tumor challenge compared with buffer-treated mice (P < 0.001). Eighty percent of mice who received a single HspE7 immunization and 95% who received a prime-boost immunization were protected (i.e., tumor free) when challenged at 5 weeks postimmunization (Fig. 9A and B, panels “b” and “c”). When tumor challenge was delayed to 13 weeks postimmunization, mice who had received a prime-boost immunization demonstrated significantly better tumor protection than mice who received a single immunization (P < 0.005). Mice receiving a prime-boost immunization 13 weeks prior to tumor challenge maintained a high level (84%) of protection (Fig. 9A and B, panel “g”), while those mice who received a single immunization demonstrated reduced protection (44%) when the tumor challenge was given at 13 weeks postimmunization (Fig. 9A and B, panel “f”). For those mice in which HspE7 immunization failed to prevent tumor take, the rates of tumor growth were much lower than those observed in buffer-immunized control mice (Fig. 9B, panel “a” versus panels “b” to “g”).

FIG. 9.

HspE7-induced memory T cells protect mice against TC-1 tumor challenge. C57BL/6 mice (13/group) were given either a single immunization with 400 μg HspE7 (1× HspE7) or two immunizations with an 8-week interval (2× HspE7). The immunizations were staggered so that the tumor challenge occurred on the same day for all groups, either 5, 9, or 13 weeks after the second immunization. The mice were challenged subcutaneously with TC-1, an E7-expressing murine tumor cell line. (A) Tumor incidence: percentage of tumor-bearing mice. (B) Individual tumor volume. Data shown here are the combined results for three independent experiments.

This study demonstrates that a single HspE7 immunization is capable of eliciting long-lasting memory CD8+ T cells and conferring protection against murine TC-1 tumor challenge. However, two HspE7 immunizations protect a higher proportion of mice for a longer duration.

DISCUSSION

The treatment of chronic viral disease, such as HPV infection, will require therapeutic interventions which induce strong antiviral cellular immune responses to eradicate the persistent infection and which lead to the formation of long-lived antiviral memory responses for preventing reinfection. Previously, we had demonstrated that HspE7 immunization could prevent outgrowth of an E7-expressing tumor cell line (TC-1) and eradicate established E7-expressing tumors (10). Further, it was demonstrated that tumor elimination occurred through a CD8-dependent cellular immune response. The current study extends the findings of Chu et al. by exploring the ability of HspE7 to induce long-lived E7-specific cellular immune responses, both in immunocompetent and in MHC II-deficient mice. We demonstrate that HspE7 elicits potent E7-specific CD8+ T cells, which can differentiate into memory T cells with effector functions in the absence of CD4+ T-cell help. Further, the current study explores the optimum immune regimen for inducing long-lived immunity to E7-expressing cells.

Memory T cells are well suited to respond to foreign antigens expressed by infectious agents and tumor cells because they are present at higher frequencies, undergo vigorous secondary expansion, and persist for extended periods due to antigen-independent homeostatic turnover (3, 20, 21, 47). Moreover, memory T cells also respond rapidly upon a reencounter with cognate antigen. We have observed consistent boosting effects when the two immunizations are separated by 8 weeks (Fig. 2B). These results are consistent with reports in the literature indicating that vaccine boosts should be separated by a significant length of time to allow the effectors to differentiate into memory cells and reset their responsiveness to antigens (1, 16, 20, 48).

In a previous study, we demonstrated that two HspE7 immunizations with a 2-week interval were able to protect mice challenged with TC-1 tumor cells 12 days after the second immunization (10). We further demonstrate herein that a single HspE7 immunization as well as the prime-boost regimen are capable of eliciting memory CD8+ T cells and conferring protection against murine TC-1 tumor challenge 13 weeks after the second immunization (Fig. 3 and 9). The observation that two HspE7 immunizations protect a higher proportion of mice for a longer duration may be explained by the higher numbers of memory CD8+ T cells and the higher level of cytolytic activity observed after the boost immunization (Fig. 3). Similar to the data observed for viral and bacterial infections (4, 16), our results show a higher amplitude of expansion and a prolonged contraction phase after secondary HspE7 immunization. The data presented in this study are also in agreement with the concept that a higher number of memory cells provides better protection against tumor challenge and/or pathogen reinfection (5, 44).

Using noninfectious antigens and certain viral infections, Bourgeois and others demonstrated that CD4+ help influences CD8+ primary responses (5, 8, 46). In contrast, requirement for CD4+ help in primary CD8+ expansion was not detected in some noninflammatory antigens and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) and Listeria infection models (19, 35). In this study, we have used MHC-II KO mice to show that HspE7 fusion protein is able to induce primary CD8+ responses with effector functions in the absence CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5A). The abilities of Hsp fusion proteins to induce antigen-specific CTL independent of CD4+ help indicate that these soluble immunogens can provide activation and maturation signals to antigen-presenting cells (APC) perhaps via the Toll-like receptor or other receptors of innate immunity to initiate an immune response (9, 32). Hsp fusion proteins may also activate APC via other pathways; for example, Lazarevic and colleagues have recently shown that Mycobacterium tuberculosis Hsp70 can bind to CD40 on APC and mimic CD40L-mediated activation (22).

Recent experimental data have led to the notion that CD4+ help is absolutely required for the generation and maintenance of memory CD8+ T cells capable of efficient recall responses to antigen (6, 7, 19, 34, 35, 39, 40, 49). For example, Janssen and colleagues evaluated the role of CD4+ T cells in the CD8+ immune responses to cross-presented antigens and to a viral infection with LCMV (19); Shedlock and Shen studied the responses to vaccinia virus expressing GP33 from LCMV (35); Sun and Bevan examined the effects of CD4+ T cells in an infection with recombinant Listeria monocytogenes expressing OVA or LCMV GP33 (39). In all these studies, activation and differentiation of antigen-specific T cells in the primary immune responses did not require CD4+ help. However, the memory CD8+ T cells primed in the absence of CD4+ T cells not only proliferated very poorly when rechallenged with antigen but also secreted low levels of cytokines. In marked contrast to these studies, we have shown that memory CD8+ T cells primed by HspE7 do not require CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5B to D). These CD4-independent memory CD8+ T cells primed by HspE7 are fully functional in that they display cytolytic activity and cytokine secretion once they are generated (Fig. 5 and 6). They also display similar proliferative capacities upon a reencounter with antigen (Fig. 6C and 7D). The differences in the magnitudes of the CD8+ responses (Fig. 5B to D) are most likely due to the fact that fewer CD8+ T cells are primed in the MHC-II KO mice than in the wild-type mice (Fig. 6A). Although CD4+ T cells are not absolutely required, the suboptimal response detected in MHC-II KO mice does imply that HspE7 fusion protein is able to induce MHC II-restricted CD4+ T cells and these CD4+ T cells can provide help for the optimal induction of CD8+ responses as seen in the wild-type mice (Fig. 5, 6, and 7). Due to the limitation in the number of antigen-specific events, we are unable to determine the phenotype and functional maturation of these memory T cells and compare them on a per-cell basis in our study.

Besides IFN-γ and TNF-α secretion from the restimulated splenocytes, we have shown that only the HspE7-immunized splenocytes from wild-type mice secrete GM-CSF and IL-5 after a reencounter with antigen in vitro (Fig. 8A and B). It has been shown that GM-CSF is critical for DC survival and differentiation in vitro. GM-CSF is also able to enhance the abilities of DCs to present antigens to stimulate T cells (26). It would be interesting to investigate whether GM-CSF can compensate for CD4+ help during CD8+ priming and memory maintenance in MHC-II KO mice after HspE7 immunization. The ability of HspE7 to stimulate the antigen-specific T cells, as well as innate immune cells, to secrete various cytokines provides further understanding of the mechanisms of its therapeutic potential.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that HspE7 induces potent antigen-specific CD8+ T cells with cytolytic and cytokine-secreting functions. These CD8+ T cells can differentiate into long-lasting memory T cells with effector functions in the absence of CD4+ T cell help, although the optimal levels of memory CD8+ T cells are established in the presence of CD4+ T-cell help. The HspE7-induced memory CD8+ T cells persist for at least 17 weeks and confer protection against murine TC-1 tumor challenge. The CD4+-independent nature of the CD8+ responses makes HspE7 an attractive candidate for therapy for individuals with compromised CD4+ function, such as those with invasive cancer and/or human immunodeficiency virus infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Larry S. D. Anthony for valuable discussions and critical review of the manuscript. The expert technical assistance of Mary Anderson, Melany Nauer, and LiJuan Sun is greatly appreciated. We also thank Susan Albrechtson and Stacey Spratt for the excellent animal care.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed, R., and D. Gray. 1996. Immunological memory and protective immunity: understanding their relation. Science 272:54-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthony, L. S., H. Wu, H. Sweet, C. Turnnir, L. J. Boux, and L. A. Mizzen. 1999. Priming of CD8+ CTL effector cells in mice by immunization with a stress protein-influenza virus nucleoprotein fusion molecule. Vaccine 17:373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badovinac, V. P., and J. T. Harty. 2006. Programming, demarcating, and manipulating CD8+ T-cell memory. Immunol. Rev. 211:67-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badovinac, V. P., K. A. Messingham, S. E. Hamilton, and J. T. Harty. 2003. Regulation of CD8+ T cells undergoing primary and secondary responses to infection in the same host. J. Immunol. 170:4933-4942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badovinac, V. P., K. A. Messingham, A. Jabbari, J. S. Haring, and J. T. Harty. 2005. Accelerated CD8+ T-cell memory and prime-boost response after dendritic-cell vaccination. Nat. Med. 11:748-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourgeois, C., B. Rocha, and C. Tanchot. 2002. A role for CD40 expression on CD8+ T cells in the generation of CD8+ T cell memory. Science 297:2060-2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourgeois, C., and C. Tanchot. 2003. CD4 T cells are required for CD8 T cell memory generation. Eur. J. Immunol. 33:3225-3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourgeois, C., H. Veiga-Fernandes, A. M. Joret, B. Rocha, and C. Tanchot. 2002. CD8 lethargy in the absence of CD4 help. Eur. J. Immunol. 32:2199-2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho, B. K., D. Palliser, E. Guillen, J. Wisniewski, R. A. Young, J. Chen, and H. N. Eisen. 2000. A proposed mechanism for the induction of cytotoxic T lymphocyte production by heat shock fusion proteins. Immunity 12:263-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu, N. R., H. B. Wu, T. Wu, L. J. Boux, M. I. Siegel, and L. A. Mizzen. 2000. Immunotherapy of a human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 E7-expressing tumour by administration of fusion protein comprising Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) hsp65 and HPV16 E7. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 121:216-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniel, D., C. Chiu, E. Giraudo, M. Inoue, L. A. Mizzen, N. R. Chu, and D. Hanahan. 2005. CD4+ T cell-mediated antigen-specific immunotherapy in a mouse model of cervical cancer. Cancer Res. 65:2018-2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devaraj, K., M. L. Gillison, and T. C. Wu. 2003. Development of HPV vaccines for HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 14:345-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feltkamp, M. C., H. L. Smits, M. P. Vierboom, R. P. Minnaar, B. M. de Jongh, J. W. Drijfhout, J. ter Schegget, C. J. Melief, and W. M. Kast. 1993. Vaccination with cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope-containing peptide protects against a tumor induced by human papillomavirus type 16-transformed cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 23:2242-2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frazer, I. H. 2004. Prevention of cervical cancer through papillomavirus vaccination. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:46-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Govan, V. A. 2005. Strategies for human papillomavirus therapeutic vaccines and other therapies based on the E6 and E7 oncogenes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1056:328-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grayson, J. M., L. E. Harrington, J. G. Lanier, E. J. Wherry, and R. Ahmed. 2002. Differential sensitivity of naive and memory CD8+ T cells to apoptosis in vivo. J. Immunol. 169:3760-3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harmala, L. A., E. G. Ingulli, J. M. Curtsinger, M. M. Lucido, C. S. Schmidt, B. J. Weigel, B. R. Blazar, M. F. Mescher, and C. A. Pennell. 2002. The adjuvant effects of Mycobacterium tuberculosis heat shock protein 70 result from the rapid and prolonged activation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in vivo. J. Immunol. 169:5622-5629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang, Q., J. F. Richmond, K. Suzue, H. N. Eisen, and R. A. Young. 2000. In vivo cytotoxic T lymphocyte elicitation by mycobacterial heat shock protein 70 fusion proteins maps to a discrete domain and is CD4+ T cell independent. J. Exp. Med. 191:403-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen, E. M., E. E. Lemmens, T. Wolfe, U. Christen, M. G. von Herrath, and S. P. Schoenberger. 2003. CD4+ T cells are required for secondary expansion and memory in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Nature 421:852-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaech, S. M., S. Hemby, E. Kersh, and R. Ahmed. 2002. Molecular and functional profiling of memory CD8 T cell differentiation. Cell 111:837-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaech, S. M., E. J. Wherry, and R. Ahmed. 2002. Effector and memory T-cell differentiation: implications for vaccine development. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:251-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazarevic, V., A. J. Myers, C. A. Scanga, and J. L. Flynn. 2003. CD40, but not CD40L, is required for the optimal priming of T cells and control of aerosol M. tuberculosis infection. Immunity 19:823-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, D., H. Li, P. Zhang, X. Wu, H. Wei, L. Wang, M. Wan, P. Deng, Y. Zhang, J. Wang, Y. Liu, Y. Yu, and L. Wang. 2006. Heat shock fusion protein induces both specific and nonspecific anti-tumor immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 36:1324-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin, K. Y., F. G. Guarnieri, K. F. Staveley-O'Carroll, H. I. Levitsky, J. T. August, D. M. Pardoll, and T. C. Wu. 1996. Treatment of established tumors with a novel vaccine that enhances major histocompatibility class II presentation of tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 56:21-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahdavi, A., and B. J. Monk. 2005. Vaccines against human papillomavirus and cervical cancer: promises and challenges. Oncologist 10:528-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller, G., V. G. Pillarisetty, A. B. Shah, S. Lahrs, Z. Xing, and R. P. DeMatteo. 2002. Endogenous granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor overexpression in vivo results in the long-term recruitment of a distinct dendritic cell population with enhanced immunostimulatory function. J. Immunol. 169:2875-2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizzen, L. 1998. Immune responses to stress proteins: applications to infectious disease and cancer. Biotherapy 10:173-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monnier-Benoit, S., F. Mauny, D. Riethmuller, J. S. Guerrini, M. Capilna, S. Felix, E. Seilles, C. Mougin, and J. L. Pretet. 2006. Immunohistochemical analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets in high risk human papillomavirus-associated pre-malignant and malignant lesions of the uterine cervix. Gynecol. Oncol. 102:22-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naito, S., A. C. von Eschenbach, R. Giavazzi, and I. J. Fidler. 1986. Growth and metastasis of tumor cells isolated from a human renal cell carcinoma implanted into different organs of nude mice. Cancer Res. 46:4109-4115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nimako, M., A. N. Fiander, G. W. Wilkinson, L. K. Borysiewicz, and S. Man. 1997. Human papillomavirus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in patients with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III. Cancer Res. 57:4855-4861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Padilla-Paz, L. A. 2005. Human papillomavirus vaccine: history, immunology, current status, and future prospects. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 48:226-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palliser, D., Q. Huang, N. Hacohen, S. P. Lamontagne, E. Guillen, R. A. Young, and H. N. Eisen. 2004. A role for Toll-like receptor 4 in dendritic cell activation and cytolytic CD8+ T cell differentiation in response to a recombinant heat shock fusion protein. J. Immunol. 172:2885-2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pockley, A. G. 2003. Heat shock proteins as regulators of the immune response. Lancet 362:469-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rocha, B., and C. Tanchot. 2004. Towards a cellular definition of CD8+ T-cell memory: the role of CD4+ T-cell help in CD8+ T-cell responses. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 16:259-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shedlock, D. J., and H. Shen. 2003. Requirement for CD4 T cell help in generating functional CD8 T cell memory. Science 300:337-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reference deleted.

- 37.Steele, J. C., C. H. Mann, S. Rookes, T. Rollason, D. Murphy, M. G. Freeth, P. H. Gallimore, and S. Roberts. 2005. T-cell responses to human papillomavirus type 16 among women with different grades of cervical neoplasia. Br. J. Cancer 93:248-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stern, P. L. 2005. Immune control of human papillomavirus (HPV) associated anogenital disease and potential for vaccination. J. Clin. Virol. 32(Suppl. 1):S72-S81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun, J. C., and M. J. Bevan. 2003. Defective CD8 T cell memory following acute infection without CD4 T cell help. Science 300:339-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun, J. C., M. A. Williams, and M. J. Bevan. 2004. CD4+ T cells are required for the maintenance, not programming, of memory CD8+ T cells after acute infection. Nat. Immunol. 5:927-933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Todd, R. W., S. Roberts, C. H. Mann, D. M. Luesley, P. H. Gallimore, and J. C. Steele. 2004. Human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16-specific CD8+ T cell responses in women with high grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Int. J. Cancer 108:857-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valdespino, V., C. Gorodezky, V. Ortiz, A. M. Kaufmann, E. Roman-Basaure, A. Vazquez, and J. Berumen. 2005. HPV16-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses are detected in all HPV16-positive cervical cancer patients. Gynecol. Oncol. 96:92-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Eden, W., A. Koets, P. van Kooten, B. Prakken, and R. van der Zee. 2003. Immunopotentiating heat shock proteins: negotiators between innate danger and control of autoimmunity. Vaccine 21:897-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veiga-Fernandes, H., U. Walter, C. Bourgeois, A. McLean, and B. Rocha. 2000. Response of naive and memory CD8+ T cells to antigen stimulation in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 1:47-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Villada, I. B., M. M. Barracco, M. Ziol, A. Chaboissier, N. Barget, S. Berville, B. Paniel, E. Jullian, T. Clerici, B. Maillere, and J. G. Guillet. 2004. Spontaneous regression of grade 3 vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia associated with human papillomavirus-16-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses. Cancer Res. 64:8761-8766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, J. C., and A. M. Livingstone. 2003. Cutting edge: CD4+ T cell help can be essential for primary CD8+ T cell responses in vivo. J. Immunol. 171:6339-6343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welsh, R. M., L. K. Selin, and E. Szomolanyi-Tsuda. 2004. Immunological memory to viral infections. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22:711-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wherry, E. J., V. Teichgraber, T. C. Becker, D. Masopust, S. M. Kaech, R. Antia, U. H. von Andrian, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 T cell subsets. Nat. Immunol. 4:225-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams, M. A., B. J. Holmes, J. C. Sun, and M. J. Bevan. 2006. Developing and maintaining protective CD8+ memory T cells. Immunol. Rev. 211:146-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williamson, A. L., J. A. Passmore, and E. P. Rybicki. 2005. Strategies for the prevention of cervical cancer by human papillomavirus vaccination. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 19:531-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.zur Hausen, H. 1991. Human papillomaviruses in the pathogenesis of anogenital cancer. Virology 184:9-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]