Abstract

Formation of disulfide bonds, an essential step for the maturation and exit of secretory proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), is controlled by specific ER-resident enzymes. A pivotal element in this process is Ero1α, an oxidoreductin that lacks known ER retention motifs. Here we show that ERp44 mediates Ero1α ER localization through the formation of reversible mixed disulfides. ERp44 also prevents the secretion of an unassembled cargo protein with unpaired cysteines. We conclude that ERp44 is a key element in thiol-mediated retention. It might also favour the maturation of disulfide-linked oligomeric proteins and their quality control.

Keywords: disulfide bond formation/IgM polymerization/protein secretion/quality control/redox regulation

Introduction

Intercellular communication largely depends on interactions between secreted proteins and membrane receptors. Hence, their production and release must be strictly regulated, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Proteins destined for the extracellular space fold and assemble in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), with the assistance of many chaperones and enzymes operating in optimal ionic and redox conditions. The ER quality control machinery ensures that only molecules that have attained their native structure are transported to the Golgi (Ellgaard and Helenius, 2001, 2003). Folding and assembly intermediates are retained in the ER and eventually retrotranslocated (dislocated) to the cytosol for proteasomal disposal (Ellgaard and Helenius, 2003).

The basic mechanisms of quality control are highly conserved in different cell types, despite the diversity of cargo proteins produced by individual cells during development or differentiation. How do cells discriminate between native and non-native secretory proteins? BiP and other chaperone molecules recognize hydrophobic patches on folding or assembly intermediates. Immature glycans on cargo glycoproteins are bound by calnexin and cal reticulin, two lectin-like molecules that, in collaboration with ERp57, promote folding (Ellgaard and Helenius, 2001), or EDEM, which targets terminally misfolded glycoproteins to ER-associated degradation (ERAD) (Hosokawa et al., 2001).

Studies of immunoglobulins (Ig) have revealed another mechanism of quality control, based on the recognition of exposed thiols on assembly intermediates (thiol-mediated retention; Alberini et al., 1990). In plasma cells, IgM secretion is restricted to hexamers [(µ2L2)6] or pentamers [(µ2L2)5-J], in which individual subunits are linked by disulfide bonds involving a conserved cysteine residue (C575) in the Ig-µ chain C-terminal tailpiece (µtp). C575 acts as a three-way switch, mediating assembly, retention and degradation of unpolymerized IgM (Fra et al., 1993). In B lymphocytes, polymerization is inefficient; as a result, virtually all secretory µ chains are retained in the ER and eventually degraded (Sitia et al., 1990). Thiol-mediated retention thus serves an important function in controlling IgM secretion during B-cell development. Retention of µ2L2 subunits may be also important to increase their local concentration, thereby favouring polymerization.

Whilst the ER localization of soluble resident proteins largely depends on KDEL receptor-mediated retrieval from the intermediate compartment or Golgi apparatus (Pelham and Munro, 1993; Meunier et al., 2002), ER retention seems to be the fate of thiol-exposing proteins (Isidoro et al., 1996). It is not clear how disulfide bond formation is coupled to thiol-mediated retention.

Disulfide bond formation occurs in the ER and is an essential step in the structural maturation of secretory and membrane proteins. Members of the Ero1 family transfer oxidative equivalents to cargo proteins via PDI and other ER oxidoreductases (Frand and Kaiser, 1998, 1999; Pollard et al., 1998), generally characterized by thioredoxin (trx)-like domains. However, disulfide bonds must be formed in nascent proteins (Jansens et al., 2002) and reduced in terminally misfolded proteins destined for degradation (Tortorella et al., 1998; Fagioli et al., 2001; Fassio and Sitia, 2002). The co-existence of these opposed reactions may reflect functional specialization amongst the numerous ER oxidoreductases (PDI, ERp72, ERp57, p5, etc.). Indeed, human Ero1α and β (hEROs) preferentially oxidize PDI (Mezghrani et al., 2001). On the other hand, PDI can mediate disulfide formation, isomerization or reduction depending on its redox state (Tsai et al., 2001; Tsai and Rapoport, 2002). Therefore, Ero1 activity must be tightly controlled, as some reduced PDI is necessary to catalyse disulfide isomerization and to promote ERAD (Tortorella et al., 1998; Fagioli et al., 2001). Another important question is how Ero1α and β, which lack known ER localization motif(s) (Cabibbo et al., 2000; Pagani et al., 2000), maintain their subcellular topology (Pagani et al., 2001).

In a search of the molecule(s) involved in ER redox control in mammalian cells, we recently identified ERp44 as a protein that can form mixed disulfides with hEROs as well as with unassembled Ig subunits (Anelli et al., 2002). To investigate the functional role(s) of ERp44, we have generated and characterized a panel of mutants. We show that ERp44 localizes Ero1α in the ER, and is also involved in the thiol-dependent retention of unassembled IgM subunits.

Results

ERp44 forms mixed disulfides with Ero1α and other partner proteins

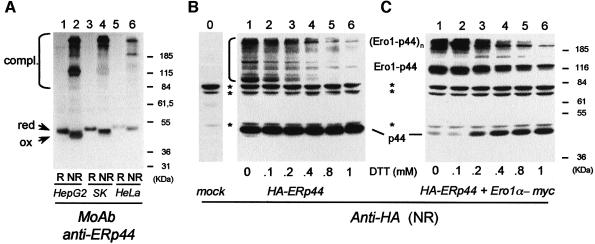

ERp44 was isolated as a protein that forms mixed disulfides with Ero1α and β, as well as with unassembled Ig subunits (Anelli et al., 2002). Endogenous ERp44 is found both in the free state and as mixed disulfides with several proteins (Figure 1A), the identity of which remains to be determined. Some bands migrate with similar mobility in the different cell lines tested, suggesting the presence of conserved ERp44 partners, such as members of the Ero1 family. When overexpressed in HeLa cells, HA-tagged ERp44 forms numerous mixed disulfides (Figure 1B, lane 1). As previously reported (Anelli et al., 2002), co-expression of Ero1α in excess resulted in the vast majority of HA-tagged ERp44 be covalently linked with the oxidoreductin (Figure 1C, lane 1).

Fig. 1. ERp44 forms mixed disulfides with Ero1α and numerous other proteins. (A) Lysates from HepG2, SK-N-BE and HeLa cells were resolved under reducing (R) or non-reducing (NR) conditions (8.8% SDS–PAGE), blotted and decorated with a monoclonal antibody (36C9) against ERp44. The migration of reduced and oxidized ERp44 monomers and covalent complexes is indicated on the left hand margin. (B) HeLa cells transiently transfected with HA-ERp44 were treated with DTT for 15 min at 37°C at the indicated concentrations prior to lysis. Aliquots were resolved under non-reducing conditions (10% SDS–PAGE), blotted and decorated with monoclonal anti-HA antibodies. Asterisks denote background bands, as indicated by the reactivity of the antibody on a lysate of mock transfected cells (lane 0). (C) HeLa cells co-transfected with HA-ERp44 and Ero1α-myc were processed as in (B). The identity of ERp44/Ero1α complexes was confirmed by decorating the blot shown in (C) with anti-myc antibodies (not shown).

When transfected cells are exposed to dithiothreitol (DTT) prior to lysis, ERp44 containing mixed disulfides disappear in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1B and C). ERp44–Ero1α complexes are particularly resistant to the reducing agent, some of them persisting at 1 mM DTT. This may suggest a special role for the ERp44–Ero1α association in mammalian cells.

ERp44 forms mixed disulfides via C29

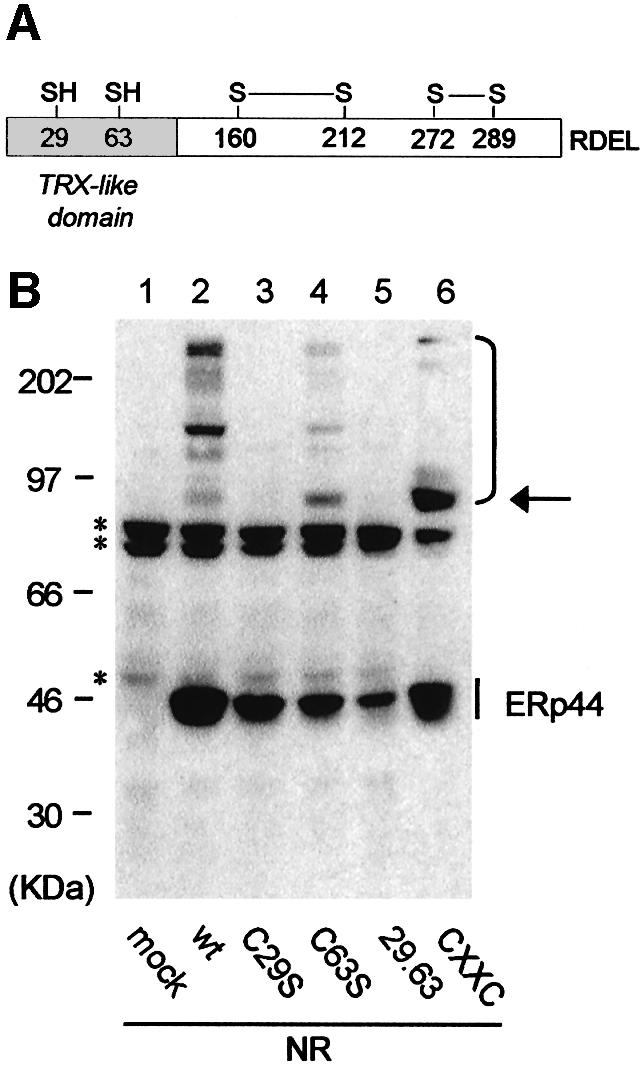

ERp44 contains six cysteines. Mass spectrometry analyses revealed that the four C-terminal cysteines are covalently linked in sequential pairs, as indicated in Figure 2A. In contrast, the two cysteines in the trx-like domain (C29 and C63) are alkylated when living cells are exposed to N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), suggesting that they are reduced (our unpublished observations). To determine their role in covalently binding partner proteins, single and double cysteine to serine replacement mutants were constructed (C29S, C63S, 29.63). In addition, a cysteine residue was inserted at position 32 to generate a CRFC motif mimicking the active site of PDI-like proteins (CxxC).

Fig. 2. ERp44 forms mixed disulfides with endogenous proteins via C29 in the trx-like domain. (A) Schematic diagram of ERp44. The redox status and pairing of the cysteines was determined by mass spectrometry analyses. (B) Lysates from HeLa cells transfected with the indicated HA-ERp44 mutants were resolved under non-reducing (NR) conditions, blotted and decorated with anti-HA. The arrow on the right points to a complex the abundance of which increases in both C63S and CxxC mutants: mass spectrometry analyses confirmed that this consists mainly if not only of ERp44 homodimers. Complexes between ERp44 and endogenous HeLa cargo proteins are indicated on the right hand margin. Asterisks denote background bands (see Figure 1B).

When C29 is absent, neither the mixed disulfides with endogenous partners (Figure 2B, compare lanes 2 and 3) nor those with Ero1α (see Figure 4 below; Supplementary figure 1, available at The EMBO Journal Online) are formed. In contrast, mutating C63 does not prevent formation of covalent complexes (Figure 2B, lane 4). These are barely detectable in the CxxC mutant (Figure 2B, lane 6), with the exception of a 90-kDa band (see arrow on the right hand margin), the intensity of which increases with respect to the wild-type (wt) molecule. MALDI-TOF peptide mass mapping suggests that this band consists of ERp44 homodimers, as only peptides derived from this protein were detected (not shown). ERp44 homodimers are formed via C29, since they are also abundant in the C63S mutant, and are probably stabilized in the CxxC mutant by the presence of a cysteine at position 32. It is likely that the stabilization of this dimeric form discourages ERp44 from binding to other client proteins. It is also possible that an intramolecular disulphide bond is formed between C29 and C32 in mutant CxxC. Taken together, these results indicate that C29 is involved in binding both Ero1α and other client proteins.

Fig. 4. ERp44 mediates the intracellular retention of Ero1α. HeLa cells were co-transfected with Ero1α-myc alone or with different HA-ERp44 mutants as indicated. Cells transfected only with the empty vector were used as control (mock). The supernatants of 3.5 × 106 cells cultured over night in Optimem (SN, upper panel) were precipitated with Concanavalin A–Sepharose (ConA) or anti-HA, as indicated. Aliquots of the lysates corresponding to 1.5 × 106 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA and resolved under reducing conditions (lower panel). Blots were sequentially decorated with anti-myc (Ero1α) and anti-HA (ERp44) antibodies.

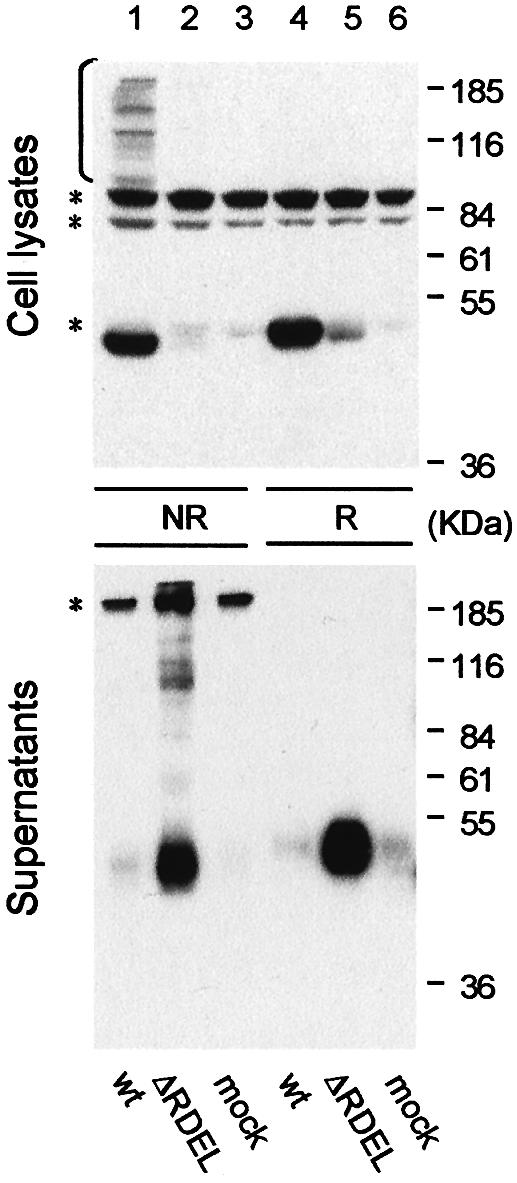

The C-terminal RDEL motif mediates ERp44 intracellular retention

Removal of the C-terminal RDEL motif allows secretion of ERp44ΔRDEL (Figure 3). Analysis under non-reducing conditions reveals that the mutant is secreted mainly as oxidized monomers. However, some covalent complexes are secreted as well (Figure 3, lane 2, bottom panel), suggesting that deleting the RDEL motif impairs the localization of ERp44, but not its capability of covalently binding substrates.

Fig. 3. The C-terminal RDEL motif mediates intracellular retention of ERp44. Aliquots from the lysates (top panel) and the anti-HA immunoprecipitated material from the supernatants (bottom panel) of HeLa cells expressing ERp44 (wt) or a mutant lacking the C-terminal RDEL motif (ΔRDEL) were resolved under reducing (R) or non-reducing (NR) conditions, and processed as in Figure 2B. Asterisks denote background bands.

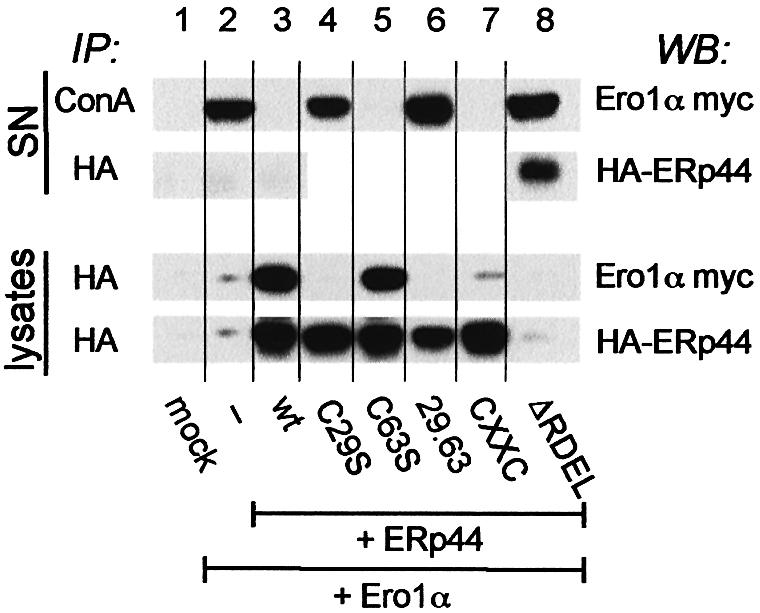

ERp44 mediates the intracellular retention of Ero1α

Endogenous Ero1α is efficiently retained intracellularly (E.Ruffato, unpublished results). In contrast, some Ero1α is secreted in the medium by transfected HeLa cells (Figure 4, lane 2, upper panel, SN), suggesting that the normal ER localization mechanisms are saturated. Since ERp44 binds Ero1α, we reasoned that ERp44 could be responsible for the intracellular retention of its partner oxidoreductin. In agreement with this, overexpressing wt ERp44 prevents the secretion of co-transfected Ero1α (Figure 4, lane 3, upper panel). The co-expression of the secreted ERp44ΔRDEL mutant does not impede the secretion of Ero1α (Figure 4, lane 8, upper panel). Likewise, neither C29S nor the double mutant 29.63 prevent the secretion of Ero1α (Figure 4, lanes 4 and 6, upper panel), indicating that the presence of C29 is essential to mediate retention. In contrast, the mutant in C63 effectively abolishes Ero1α secretion (Figure 4, lane 5). Accordingly, Ero1α does not co-precipitate with mutants that do not mediate its retention (lower panel), confirming that retention correlates with binding to ERp44. However, the CxxC mutant is able to mediate retention, despite the fact that only few covalent complexes with Ero1α are detected at steady state (Figure 4, lane 7, lower panel; Supplementary figure 1). This correlates with the different kinetics with which Ero1α forms stable covalent interactions with ERp44 wt and the CxxC mutant in pulse–chase assays (Supplementary figure 2): the amount of Ero1α co-immunoprecipitated with ERp44 wt remains almost constant during the chase, while the interaction with the CxxC mutant becomes detectable only at later times. Therefore, the possibility of forming reversible mixed disulfides via C29 is essential for retention. Retention of endogenous Ero1α in non-transfected cells probably reflects the fact that normally ERp44 is in excess with respect to Ero1α (vanAnken et al., 2003).

ERp44 interacts with unassembled Ig-µ chains and mediates their retention

Having shown that ERp44 mediates Ero1α retention, we sought to determine whether it also controls the intracellular transport of cargo proteins. Secretory IgM offer a good model system to analyse the mechanisms that couple assembly and quality control of oligomeric proteins. The retention (and degradation) of unassembled µ chains depends on at least two elements: the first constant domain (CH1), which in the absence of L chains interacts with BiP, and C575 in the C-terminal tailpiece, which mediates retention of unpolymerized subunits. Removal of both elements allows µ chain secretion (Sitia et al., 1990), whilst the addition of exogenous reducing agents is sufficient to induce µΔCH1 secretion (Alberini et al., 1990; Valetti and Sitia, 1994).

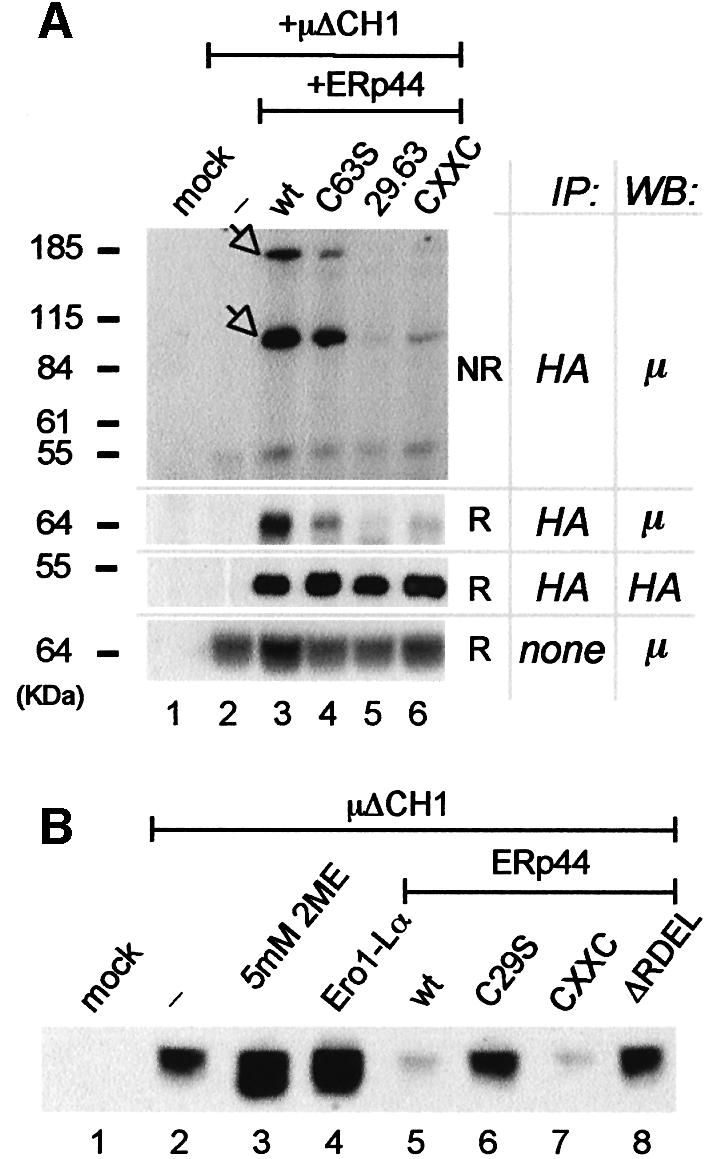

HA-ERp44 is also able to form mixed disulfides with Ig-J, K (Anelli et al., 2002) and µΔCH1 chains (Figure 5A). As in the case of Ero1α, C29 is essential for covalent interaction with µΔCH1 (Figure 5A, lane 5). In view of these findings, we asked whether the interaction with ERp44 could be important for retention of µΔCH1 in the ER, as it is for Ero1α. We took advantage of the fact that retention of µΔCH1 is not as efficient in HeLa cells as it is in myeloma cells (T.Anelli, A.Mezghrani and R.Sitia, unpublished observations): as a result, some µΔCH1 chains are detected in the medium of HeLa transfectants (Figure 5B, lane 2). µΔCH1 secretion can be increased further by treating HeLa cells with 2-mercaptoethanol (2ME; Figure 5B, lane 3), confirming the involvement of thiol-mediated retention mechanisms (Alberini et al., 1990; Valetti and Sitia, 1994).

Fig. 5. ERp44 binds covalently to unassembled µ chains and retains them intracellularly. (A) ERp44 forms mixed disulfides with µΔCH1. Lysates of 3 × 106 HeLa cells transfected with µΔCH1 alone or with HA-ERp44 (wt or mutated), or with the empty vector (mock) were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA, resolved under non-reducing or reducing conditions and immunoblotted with anti-µ and anti-HA antibodies, as indicated. Based on their mobility, the two main bands recognized by the anti-µ antibody likely correspond to µΔCH1 monomers and dimers covalently linked to HA-ERp44 (see arrowheads). As a control of the amount of µΔCH1 in each sample, lysates of 1.2 × 105 cells of each transfection were resolved under reducing conditions and decorated with anti-µ antibody. Note that the mutant CxxC binds less µΔCH1 than wt molecules, at steady state. (B) The supernatants of HeLa cells transfected as indicated were collected after 4 h of culture in Optimem, concentrated with ConA Sepharose and resolved under reducing conditions; blots were decorated with anti-μ. Lane 3 shows the material precipitated from the supernatant of cells treated with 5 mM 2ME for 4 h.

As observed for Ero1α, the co-expression of HA-ERp44 wt prevents µΔCH1 secretion (Figure 5B, lane 5). The C29S mutant is inactive (Figure 5B, lane 6), confirming the role of C29 also in µΔCH1 retention. As expected, the ERp44ΔRDEL mutant is also inactive (Figure 5B, lane 8). The CxxC mutant is almost as efficient as ERp44 wt in preventing µΔCH1 secretion (Figure 5B, lane 7, Supplementary figure 2C), although it covalently binds less µΔCH1 at steady state (Figure 5A, lane 6) and displays slower kinetics of co-precipitation in pulse–chase assays (Supplementary figure 2B). Therefore, ERp44 is capable of mediating retention of unassembled µ chains. Further evidence for this conclusion comes from the results obtained by co-expressing Ero1α and µΔCH1 in HeLa cells. Since the overexpression of Ero1α displaces ERp44 from many endogenous substrates (Figure 1C), we reasoned that excess Ero1α might decoy endogenous ERp44 and inhibit µΔCH1 retention. In agreement with this, the co-expression of Ero1α induces µΔCH1 secretion (lane 4) to an extent comparable to 2ME treatment.

ERp44 covalently binds to C575 in the µtp

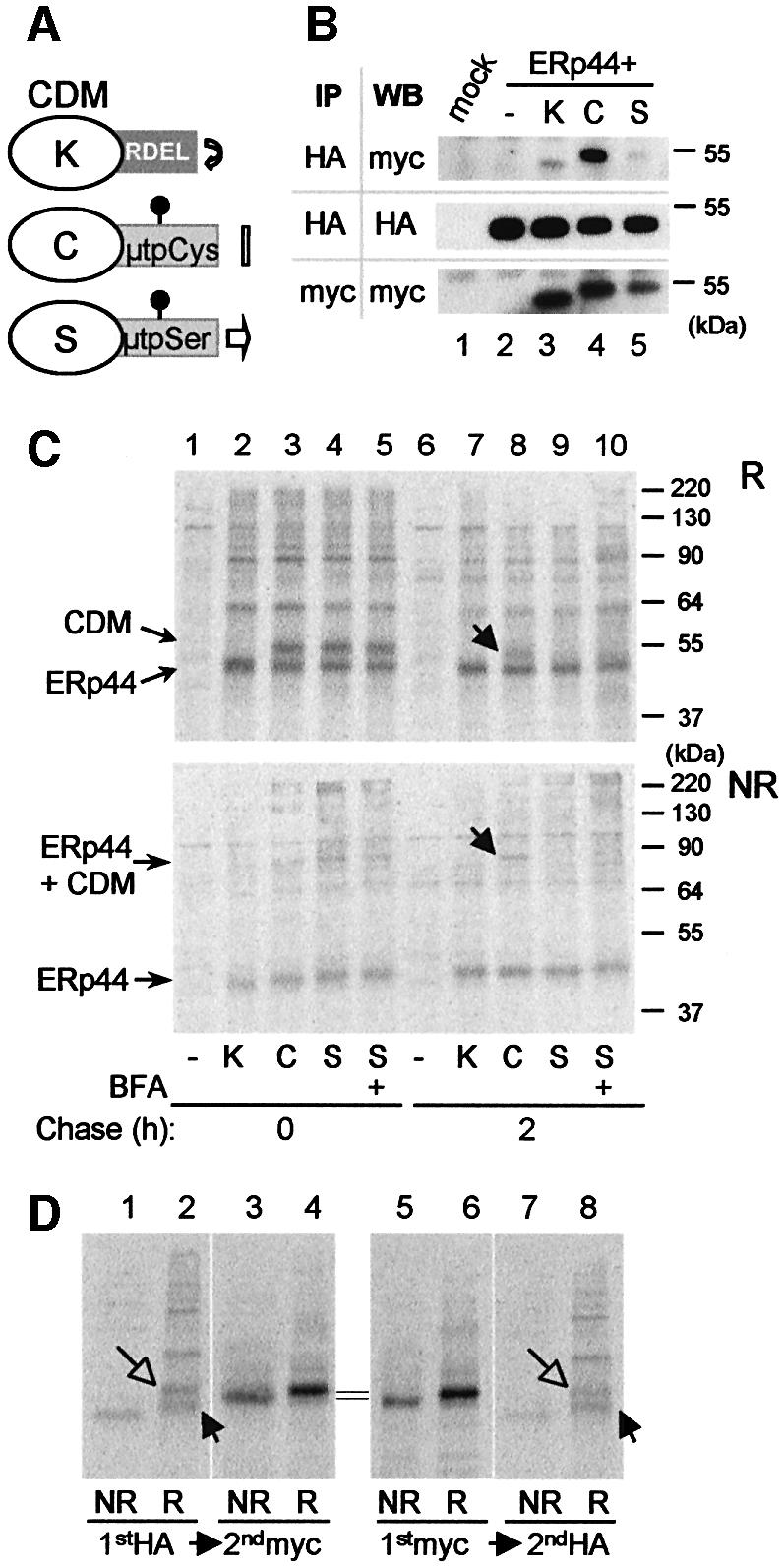

The above results suggested that ERp44 covalently binds C575 in the µtp (Sitia et al., 1990), thereby contributing to the retention of unassembled IgM subunits. To prove that this is indeed the case, we made use of chimeric proteins, in which a myc-tagged cathepsin D is extended with either a KDEL sequence or with the µtp containing a cysteine or a serine in the penultimate position (CDMK, CDMµtpCys and CDMµtpSer; see Figure 6A). When a cysteine is present in the tailpiece, CDMµtpCys are retained and degraded, whilst CDMµtpSer are transported to the Golgi (Isidoro et al., 1996); CDMK are localized in the ER by retrieval mechanisms (Fra et al., 1993).

Fig. 6. ERp44 binds to C575 in the µtp. (A) Scheme of the cathepsin D chimeras utilized (Fra et al., 1993; Pelham and Munro, 1993; Isidoro et al., 1996). C-terminally myc-tagged cathepsin D constructs were further extended with SEKDEL (K) or the 20 residue µtp with a cysteine (C) or a serine (S) in the penultimate position (Fra et al., 1993). The µtp contains an N-glycan. As described previously, CDMµtpSer is transported to the Golgi and in part secreted, while CDMK and CDMtpCys are localized in the ER, the former because of its KDEL-dependent retrieval and the latter because of thiol-mediated retention. Only CDMK accumulates intracellularly with phosphorylated glycans (Isidoro et al., 1996). (B) Interaction between ERp44 and CDM chimeras at steady state. Lysates of 1 × 106 HeLa cells transfected with the vector alone (mock), or with HA-ERp44 alone or with different CDM chimeras were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA or with anti-myc, as a control. The immunoprecipitated material was then resolved in SDS–PAGE under reducing conditions, and decorated with anti-myc or anti-HA antibodies, as indicated. Only a very little amount of CDMK and CDMµtpSer co-precipitated with ERp44 when compared with CDMµtpCys. Note that the µtp confers higher electrophoretic mobility to the chimeras, also owing to the presence of a glycosylation site [also see (A)]. (C) HeLa cells co- transfected with HA-ERp44 and cathepsin D chimeras as indicated were pulsed for 15 min with [35S]amino acids and chased for 0 (lanes 1–5) or 2 h (lanes 6–10) with or without BFA (1 µg/ml). The anti-HA immunoprecipitated materials obtained from cell lysates were resolved under reducing (R, top panel) or non-reducing (NR, bottom panel) conditions. While at the beginning of the chase all CDM chimeras co-precipitate with ERp44, after 2 h chase only CDMµtpCys remains covalently associated with it (lane 8, see arrows). The additional bands present in lanes 2–5 probably correspond to other HeLa endogenous proteins that associate with HA-ERp44, and are released with different kinetics (compare lanes 7–10). (D) Only a fraction of CDMµtpCys is bound to ERp44 at steady state. Lysates of HeLa cells co-transfected with HA-ERp44 and CDMµtpCys, and chased for 2 h after a 15 min pulse of radioactive aminoacids [see (B)] were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-HA or with anti-myc; the leftover of these first IPs were subsequently subjected to IP with anti-myc or anti-HA, respectively. Note that anti-myc antibodies do not co-precipitate ERp44, probably because the myc epitope is masked in the ERp44–CDM complexes. About 10% of CDMµtpCys is bound to ERp44 after 2 h of chase. Closed and open arrows indicate reduced ERp44 and CDM, respectively.

First, we employed immunoprecipitation–western blot assays to determine whether ERp44 interacts preferentially with CDMµtpCys at steady state. Indeed, the CDMµtpCys gave an intense signal (Figure 6B, lane 4). However, some CDMK or CDMµtpSer were also co-immunoprecipitated with ERp44, albeit in lower amounts (Figure 6B, lanes 3 and 5). This interaction could reflect transient binding of ERp44 to the maturing cathepsin domain, which is stabilized by intra-chain disulfide bonds in its native state. To determine whether this is indeed the case, we performed pulse–chase assays (Figure 6C). Soon after the pulse, ERp44 bound all three constructs (Figure 6C, lanes 2–5). Binding was mainly covalent, as indicated by the presence of high molecular weight bands in non-reducing gels (Figure 6C, bottom panel). After a 2 h chase, however, anti-HA antibodies co-precipitated only CDMµtpCys (Figure 6C, lane 8). Binding with ERp44 does not correlate with ER residency, as it is negligible with the CDMK mutant (Figure 6C, lane 7), or when the exit of CDMµtpSer from the ER is prevented with brefeldin A (Figure 6C, lane 10). Therefore, stable interactions with ERp44 require the presence of the penultimate cysteine within the µtp. These findings indicate that ERp44 transiently binds to cysteine(s) within the cathepsin domain, detaching when folding is complete (Fra et al., 1993), as observed for K chains (Anelli et al., 2002). In contrast, binding to the tailpiece cysteine persists, thus contributing to ER retention. Immunoprecipitation with anti-HA and subsequent immunoprecipitation with anti-myc on the leftover of the first one (Figure 6D) revealed that ∼10% of newly synthesized CDMµtpCys molecules were associated to HA-ERp44 after 2 h of chase (Figure 6D, compare lanes 2 and 4). The reverse treatment showed that anti-myc antibodies were unable to precipitate the CDMµtpCys–ERp44 complexes. This may reflect inaccessibility of the myc tag, which lies immediately upstream of the tailpiece that binds ERp44.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that ERp44 utilizes C29 to bind Ero1α and other client proteins. Sequence alignments and computer modelling predict that C29 lies in the position normally occupied by the most reactive residue of trx domains, the first cysteine of the canonical CxxC motif. When C29 is replaced by a serine, ERp44 no longer forms mixed disulfides with Ero1α, Ig subunits and other endogenous proteins. In contrast, replacing C63 has minor effects on the formation of covalent complexes, apart from the fact that ERp44 covalent homodimers become more abundant. This suggests that C63 might be important to resolve homodimers. In contrast, the presence of an additional cysteine in the interacting surface of ERp44CxxC facilitates homodimer formation. However, the CxxC mutant displays a significantly reduced number of stable covalent interactions, perhaps because C29 becomes also involved in intra-molecular interactions with the downstream cysteine.

Retaining Ero1 in the ER

Since secretory proteins form their disulfide bonds in the ER, it is crucial that the necessary components of the redox machineries reside in this compartment. HeLa cells efficiently retain endogenous Ero1α molecules (E.Ruffato, A.Mezghrani and R.Sitia, unpublished results), despite the absence of known ER localization motifs. In contrast, overexpressed Ero1α is in part secreted (Figure 4), probably owing to saturation of the normal localization mechanism(s). How is human Ero1α retained? One possibility is via binding to PDI (Mezghrani et al., 2001). However, it would seem difficult to saturate the high pool of this oxidoreductase, unless Ero1α binds to a subset of PDI molecules (Tsai and Rapoport, 2002). Also, the interactions with ER membrane components could prevent transport to the Golgi of endogenous Ero1α (Cabibbo et al., 2000). Our results indicate that ERp44 plays a crucial role in localizing Ero1α in the ER. When wt ERp44 is expressed in excess, virtually all overexpressed Ero1α remains intracellular. Retention requires the presence of C29, and correlates with the capability of ERp44 to form mixed disulfides with Ero1α (Figure 1C; Supplementary figure 1; Anelli et al., 2002). Mass spectrometry analyses (not shown) reveal that many cysteines in transfected Ero1α are exposed and in the thiol state, and this probably makes the oxidoreductin a privileged client of ERp44. All single and some double cysteine-replacement Ero1α mutants retain the ability of covalently binding ERp44 (G.Bertoli, T.Simmen, T.Anelli, S.Nerini Molteni and R.Sitia, unpublished results). Therefore, Ero1α is a multivalent substrate for ERp44, capable of competing with endogenous substrates when overexpressed (Figure 1, compare B with C). Pulse–chase assays confirm that ERp44 preferentially interacts with Ero1α (Supplementary figure 2A). The two molecules covalently associate with each other with extreme rapidity, complexes being abundant already at the end of a short pulse. In contrast, µΔCH1 can be co-immunoprecipitated with ERp44 only later during the chase (Supplementary figure 2B). The higher affinity of ERp44 for Ero1α probably reflects the different physiology of the interactions. While Ero1α is an ER resident protein, Ig-µ chains are models of cargo molecules in the process of forming covalent oligomers.

Retention by formation of reversible disulfide bonds with the ER matrix

Studies on Ig-L chains led us to propose that retention may be achieved by formation of reversible disulfide bonds with proteins of the ER matrix (Reddy et al., 1996; Reddy and Corley, 1999). The results obtained with a µ chain deleted of the CH1 domain (µΔCH1) demonstrate that ERp44 plays an important role also in thiol-mediated cargo retention. The retention of µΔCH1 chains, which largely depends on thiol-mediated mechanisms involving C575 in the tailpiece (Alberini et al., 1990; Sitia et al., 1990), is less efficient in HeLa than in myeloma cells. This may reflect a lower relative concentration of ERp44 in HeLa cells, or/and different redox conditions or chaperone composition in the ER (A.Mezghrani, E.Ruffato and R.Sitia, unpublished observations). Expression of wt ERp44, but not of the inactive C29S mutant, efficiently prevents µΔCH1 secretion (Figure 5B). In contrast, µΔCH1 secretion is increased when Ero1α is co-expressed. It is possible that Ero1α, a privileged ERp44 partner (Figure 1C), acts as a decoy for endogenous ERp44, ‘distracting’ it from its duty of retaining µΔCH1. Alternatively, Ero1α could also favour C575 oxidation with small thiols (Reddy et al., 1996). Overexpressing ERp44ΔRDEL does not significantly increase µΔCH1 secretion, confirming that retrieval from the Golgi plays a minor role in thiol-mediated ER localization (Isidoro et al., 1996). It will be of interest to determine the molecular composition of the mixed disulphides containing ERp44 ΔRDEL present in the spent medium of HeLa transfectants, as these species could represent endogenous ERp44 substrates.

The above findings identify ERp44 as a key element in thiol-mediated retention of oxidative folding and assembly intermediates in the early compartments of the secretory route. Owing to the presence of a C-terminal RDEL sequence, ERp44 molecules are retrieved to the ER. Here, newly made proteins with unpaired cysteines interact with ERp44 and other proteins that are part of the matrix. Provided that a RDEL-localization device is present, overexpression of ERp44 increases the capacity of the matrix. The interactions with ERp44 and other proteins of the matrix may delay the exit from the ER and eventually dispatch terminally misfolded or unassembled molecules to the cytosol for degradation (Fra et al., 1993; Fagioli et al., 2001). This model may explain why CDMµtpCys appears to be retained in earlier compartments than CDMK (Isidoro et al., 1996).

Should we envisage a homogeneous matrix in the ER, or rather a patchwork of specialized subsections? Hendershot and colleagues recently proposed that BiP, GRP94, UGT and other ER-resident folding assistants interact with each other to form supramolecular complexes that may be important for folding and quality control (Meunier et al., 2002). Interestingly, neither calnexin-calreticulin nor ERp44 and Ero1α were found in this complex. It is tempting to speculate that different chaperone complexes exist within the ER, acting sequentially as cargo proteins complete their maturation. During IgM biogenesis, µ-L assembly (largely patrolled by BiP and GRP94; Hendershot et al., 1987; Melnick et al., 1994) precedes C575-dependent polymerization, and this may reflect interaction with different chaperone complexes.

An important result is that the CxxC mutant is also effective in retaining Ero1α and µΔCH1 despite mixed disulfides with the client proteins are formed later in the chase (Supplementary figure 2) and are much less abundant at steady state (Figure 4; Supplementary figure 1) with respect to the wt molecule. These data imply that it is the capability of forming mixed disulfides with ERp44 that is important for retention. They also suggest that rather few active ERp44 molecules are sufficient to mediate retention. Moreover, the complexes detected at the beginning of chase seem non-essential for retention, as the CxxC mutant is able to retain too. Hence, ERp44 might act as a late ‘check point’ before cargo exit from the ER, receiving molecules that have already undergone BiP or calnexin-mediated quality control. Consistent with this, deletion of the RDEL motif causes rapid secretion of ERp44.

Our findings demonstrate that ERp44 uses C29 to establish disulfide bonds with client proteins with unpaired cysteines, hence mediating their retention. What catalyses the formation of covalent bonds between ERp44 and its substrates? The oxidative power of Ero1α could be used in intramolecular (ERp44–Ero1α) and intermolecular (ERp44–µΔCH1) reactions as well. However, the finding that Ero1α overexpression weakens µΔCH1 retention argues against this possibility. It is also possible that ERp44 homodimers be the active form. This important question clearly deserves further investigation.

Owing to the similarities between yeast and mammalian oxidative folding pathways, epitomized by the observation that both human Ero1α and Ero1β complement a defective yeast strain (Cabibbo et al., 2000; Pagani et al., 2000), it is perhaps surprising that yeast do not have an ERp44 homologue. Besides the similarities, however, there are important differences between yeast and human Ero1 members. For instance, yeast Ero1 has an essential C-terminal tail that serves to associate the molecule to the membrane. This tail is absent from hEROs, which nonetheless associate in part with the membranes (Cabibbo et al., 2000; Pagani et al., 2000). Since hEROs do not contain hydrophobic regions able to mediate membrane insertion, they may interact with ERp44 and other proteins to attain complete localization and function. It is somehow surprising that, whilst the main oxidase activity is conserved in the two distant species, the localization mechanisms diverged. The use in mammalian cells of an in trans device to mediate Ero1 localization may allow further levels of regulation, controlling its topology and/or function (Anelli et al., 2002; Tsai et al., 2002).

Another interesting feature is that a similar localization mechanism is used by Ero1α, a protein destined to reside in the ER, and by cargo proteins in transit towards the Golgi. This may have functional implications with respect to oligomerization. We have recently observed that ERp44 is up-regulated during B to plasma cell differentiation (vanAnken et al., 2003). This could solely reflect the massive ER expansion that accompanies B cell development, but an additional function can be envisaged. By retaining unassembled IgM subunits and J chains, ERp44 might play an active role in initiating polymerization. In this scenario, co-localized Ero1 molecules could deliver the oxidative equivalents required for this process.

Materials and methods

Cells and reagents

Cell lines were obtained from ATCC. DTT, 2ME, brefeldin A (BFA), NEM, iodoacetamide (IAA), trypsin, SDS and Concanavalin A Sepharose-4B were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO); fetal calf serum (FCS) and culture media were from Gibco-BRL (Milan, Italy); Lipofectin was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); and Sepharose-conjugated proteins A and G, CNBr-activated Sepharose, ECL reagents and [35S]amino acids (PROMIX) were from Amersham Biosciences (Milan, Italy). Horseradish peroxidase goat anti-mouse IgG(H+L) was from Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc. (Birmingham, AL); horseradish peroxidase goat anti-rabbit IgG was from Jackson ImmunoResearch (Baltimore, MD); and polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse IgM was from ZYMED (San Francisco, CA). Mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for myc (9E10) and HA (12CA5) were immobilized by cross-linking to protein G and protein A beads, respectively (Reddy et al., 1996) and used to precipitate tagged molecules.

Mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for ERp44 were raised using the chimera GST–ERp44 (Anelli et al., 2002) as an antigen (ARETA International S.r.l., Gerenzano, Italy): their characteristics will be described elsewhere.

Plasmids and vectors

The vectors for the expression of HA-ERp44, CDMK, CDMµtpCys and CDMµtpSer were as previously described (Fra et al., 1993; Anelli et al., 2002).

The vector for µΔCH1 expression was prepared by RT–PCR from RNA isolated from N[µΔCH1] cells (Valetti et al., 1991; Benedetti et al., 2000). The first strand cDNAs were synthesized by incubation of 1–3 µg of total RNA with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (5 U; Promega, Madison, WI) for 1 h at 42°C. The resulting first strand cDNA was then used for PCR amplification with primers containing unique restriction sites, BamHI for the forward primer (GGAATTCG CACACAGGACCTCACC) and XbaI for the reverse primer (AAAAA ATCTAGACTGGTTGAGCGCTAGCATGG). PCR product were digested and cloned in pcDNA3-1(+) (Invitrogen, Life Technologies).

To generate mutants, HA-ERp44 was excised from pcDNA3.1(–) using the restriction sites XhoI–Acc65I and inserted in pBS KSII(–). Point mutagenesis was performed using the following oligonucleotides: TA16S and TA17R for C29S; TA20S and TA21R for C63S; TA18S and TA19R for CxxC; TA22S and TA23R for ΔRDEL. The mutated sequences were then re-inserted in pcDNA3.1(–) using XhoI and Acc65I.

The double mutant 29.63 was obtained with digestion and ligation from the sequences of the two mutants C29S and C63S: the fragment obtained by digestion of the plasmid C29S pcDNA3.1(–) with HindIII (and containing the sequence for C63) was exchanged with the one obtained from the mutant C63S (encoding a serine in position 63).

Oligonucleotides

Oligonucleotides used were as follows: TA16S, GTAAATTTTTATG CTGACTGGTCCCGTTTCAGTCAGATGTTG; TA17R, CAACATCT GACTGAAACGGGACCAGTCAGCATAAAAATTTAC; TA18S, CT GACTGGTGTCGTTTCTGTCAGATGTTGCATCC; TA19R, GGATG CAACATCTGACAGAAACGACACCAGTCAG; TA20S, GTGTTTG CCAGAGTTGATAGTGATCAGCACTCTG; TA21R, CAGAGTGCT GATCACTATCAACTCTGGCAAACAC; TA22S, CTATTGAGGGA TTGAGATCTGCTTTAAGGTACC; TA23R, GGTACCTTAAAGCA GATCTCAATCCCTCAATAG.

Transfection, pulse–chase assays, immunoprecipitation and western blotting

Transient transfections and western blot analyses were performed as previously described (Pagani et al., 2000; Mezghrani et al., 2001; Anelli et al., 2002). When indicated, aliquots of supernatants or cell lysates were precipitated with Sepharose-bound Concanavalin A to concentrate glycoproteins before western blotting.

For pulse–chase assays, 48 h after transfection cells were subjected to a 30 min starvation (DMEM without methionine and cysteine, 1% dialysed FCS), pulsed for 5 or 10 min (as indicated) with [35S]amino acids (200 µCi/0,5ml; 200 µCi/9 × 106 cells) and then washed and chased for different lengths of time as indicated. At the end of each chase time, cells were treated with 10 mM NEM to block disulphide interchange and then lysed as described previously (Anelli et al, 2002). When indicated, supernatants of chase were collected, 20 mM of NEM added, and subjected to immunoprecipitation.

In-gel digestion of proteins, mass spectrometric analysis and database searching

Bands of interest were excised from the gel, subsequently cut into ∼1 × 1 mm pieces, transferred to an 0.5 ml Eppendorf tube, rinsed with water and reduced, alkylated and digested overnight with bovin trypsin as described elsewhere (Shevchenko et al., 1996).

Proteins were identified by MALDI-TOF peptide mass mapping. Briefly, 1 µl of the supernatant of the digestion was loaded onto the MALDI target using the dried droplet technique and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as matrix. MALDI-MS measurements were performed on a Voyager-DE STR (Applied Biosystems) time of flight (TOF) mass spectrometer and processed via the Data Explorer software. Proteins were unambiguously identified by searching against a comprehensive non-redundant sequence database using the program ProFound (Zhang and Chait, 2000).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Adam Benham, Ineke Braakman, Neil Bulleid, Claudio Fagioli, Anna Fassio, Erwin Ivessa, Maurizio Molinari, Silvia Nerini Molteni, Raffaella Scorza and Eelco vanAnken for helpful reagents, suggestions and discussions, and Tania Mastrandrea for secretarial assistance. This work was in part supported by the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), Ministero della Sanitá (RF 46, 96) e MIUR (CoFin and Center of Excellence in Physiopathology of Cell Differentiation) and Telethon. T.A., A.M. and T.S. were recipients of fellowships from Federazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (FIRC), European Community (CEE52106) and Telethon (380/bs), respectively.

References

- Alberini C.M., Bet,P., Milstein,C. and Sitia,R. (1990) Secretion of immunoglobulin M assembly intermediates in the presence of reducing agents. Nature, 347, 485–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anelli T., Alessio,M., Mezghrani,A., Simmen,T., Talamo,F., Bachi,A. and Sitia,R. (2002) ERp44, a novel endoplasmic reticulum folding assistant of the thioredoxin family. EMBO J., 21, 835–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti C., Fabbri,M., Sitia,R. and Cabibbo,A. (2000) Aspects of gene regulation during the UPR in human cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 278, 530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabibbo A., Pagani,M., Fabbri,M., Rocchi,M., Farmery,M.R., Bulleid,N.J. and Sitia,R. (2000) ERO1-L, a human protein that favors disulfide bond formation in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 4827–4833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellgaard L. and Helenius,A. (2001) ER quality control: towards an understanding at the molecular level. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 13, 431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellgaard L. and Helenius,A. (2003) Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 3, 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagioli C., Mezghrani,A. and Sitia,R. (2001) Reduction of inter-chain disulfide bonds precedes the dislocation of Ig-μ chains from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol for proteasomal degradation. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 40962–40967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassio A. and Sitia,R. (2002) Formation, isomerisation and reduction of disulphide bonds during protein quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Histochem. Cell Biol., 117, 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fra A., Fagioli,C., Finazzi,D., Sitia,R. and Alberini,C. (1993) Quality control of ER synthetized proteins: an exposed thiol group as a three-way switch mediating assembly, retention and degradation. EMBO J., 12, 4755–4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frand A.R. and Kaiser,C.A. (1998) The ERO1 gene of yeast is required for oxidation of protein dithiols in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Cell, 1, 161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frand A.R. and Kaiser,C.A. (1999) Ero1p oxidizes protein disulfide isomerase in a pathway for disulfide bond formation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Cell, 4, 469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot L., Bole,D., Kohler,G. and Kearney,J.F. (1987) Assembly and secretion of heavy chains that do not associate posttranslationally with immunoglobulin heavy chain-binding protein. J. Cell Biol., 104, 761–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa N., Wada,I., Hasegawa,K., Yorihuzi,T., Tremblay,L.O., Herscovics,A. and Nagata,K. (2001) A novel ER alpha-mannosidase-like protein accelerates ER-associated degradation. EMBO Rep., 2, 415–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isidoro C., Maggioni,C., Demoz,M., Pizzagalli,A., Fra,A.M. and Sitia,R. (1996) Exposed thiols confer localization in the endoplasmic reticulum by retention rather than retrieval. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 26138–26142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansens A., van Duijn,E. and Braakman,I. (2002) Coordinated nonvectorial folding in a newly synthesized multidomain protein. Science, 298, 2401–2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick J., Dul,J.L. and Argon,Y. (1994) Sequential interaction of the chaperones BiP and GRP94 with immunoglobulin chains in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature, 370, 373–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier L., Usherwood,Y.K., Chung,K.T. and Hendershot,L.M. (2002) A subset of chaperones and folding enzymes form multiprotein complexes in endoplasmic reticulum to bind nascent proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell, 13, 4456–4469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezghrani A., Fassio,A., Benham,A., Simmen,T., Braakman,I. and Sitia,R. (2001) Manipulation of oxidative protein folding and PDI redox state in mammalian cells. EMBO J., 20, 6288–6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani M., Fabbri,M., Benedetti,C., Fassio,A., Pilati,S., Bulleid,N.J., Cabibbo,A. and Sitia,R. (2000) Endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductin 1-lβ (ERO1-Lβ), a human gene induced in the course of the unfolded protein response. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 23685–23692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani M., Pilati,S., Bertoli,G., Valsasina,B. and Sitia,R. (2001) The C-terminal domain of yeast Ero1p mediates membrane localization and is essential for function. FEBS Lett., 508, 117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham H.R. and Munro,S. (1993) Sorting of membrane proteins in the secretory pathway. Cell, 75, 603–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard M.G., Travers,K.J. and Weissman,J.S. (1998) Ero1p: a novel and ubiquitous protein with an essential role in oxidative protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Cell, 1, 171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy P.S. and Corley,R.B. (1999) The contribution of ER quality control to the biologic functions of secretory IgM. Immunol. Today, 20, 582–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy P., Sparvoli,A., Fagioli,C., Fassina,G. and Sitia,R. (1996) Formation of reversible disulfide bonds with the protein matrix of the endoplasmic reticulum correlates with the retention of unassembled Ig light chains. EMBO J., 15, 2077–2085. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A., Wilm,M., Vorm,O. and Mann,M. (1996) Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem., 68, 850–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitia R., Neuberger,M., Alberini,C., Bet,P., Fra,A., Valetti,C., Williams,G. and Milstein,C. (1990) Developmental regulation of IgM secretion: the role of the carboxy-terminal cysteine. Cell, 60, 781–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortorella D., Story,C.M., Huppa,J.B., Wiertz,E., Jones,T.R. and Ploegh,H.L. (1998) Dislocation of type I membrane proteins from the ER to the cytosol is sensitive to changes in redox potential. J. Cell Biol., 142, 365–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai B. and Rapoport,T.A. (2002) Unfolded cholera toxin is transferred to the ER membrane and released from protein disulfide isomerase upon oxidation by Ero1. J. Cell Biol., 159, 207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai B., Rodighiero,C., Lencer,W.I. and Rapoport,T.A. (2001) Protein disulfide isomerase acts as a redox-dependent chaperone to unfold cholera toxin. Cell, 104, 937–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai B., Ye,Y. and Rapoport,TA. (2002) Retro-translocation of proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum into the cytosol. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 3, 246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valetti C. and Sitia,R. (1994) The differential effects of dithiothreitol and 2-mercaptoethanol on the secretion of partially and completely assembled immunoglobulins suggest that thiol-mediated retention does not take place in or beyond the Golgi. Mol. Biol. Cell, 5, 1311–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valetti C., Grossi,C.E., Milstein,C. and Sitia,R. (1991) Russell bodies: a general response of secretory cells to synthesis of a mutant immunoglobulin which can neither exit from, nor be degraded in, the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol., 115, 983–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanAnken E., Romijn,E.P., Maggioni,C., Mezgrhani,A., Sitia,R., Braakman,I. and Heck,A.J.R. (2003) Sequential waves of functionally related proteins are expressed when B cells prepare for antibody secretion. Immunity, 18, 243–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. and Chait,B.T. (2000) ProFound: an expert system for protein identification using mass spectrometric peptide mapping information. Anal. Chem., 72, 2482–2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]