Abstract

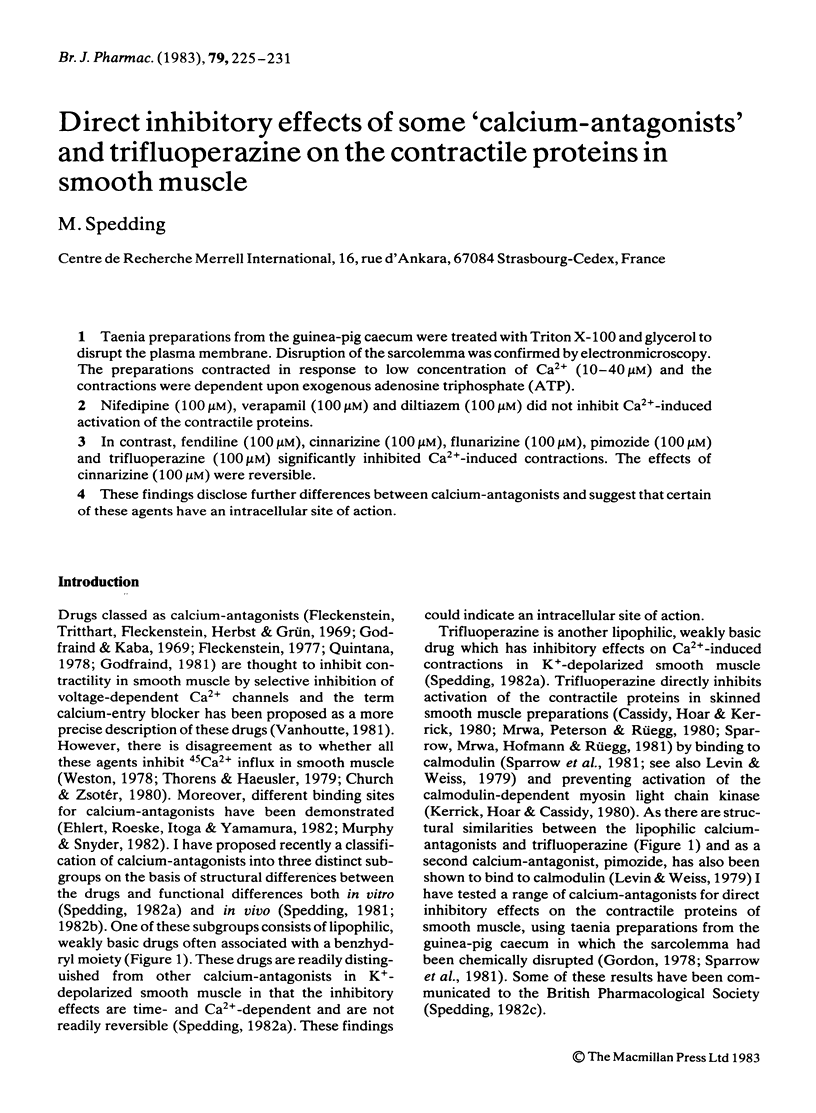

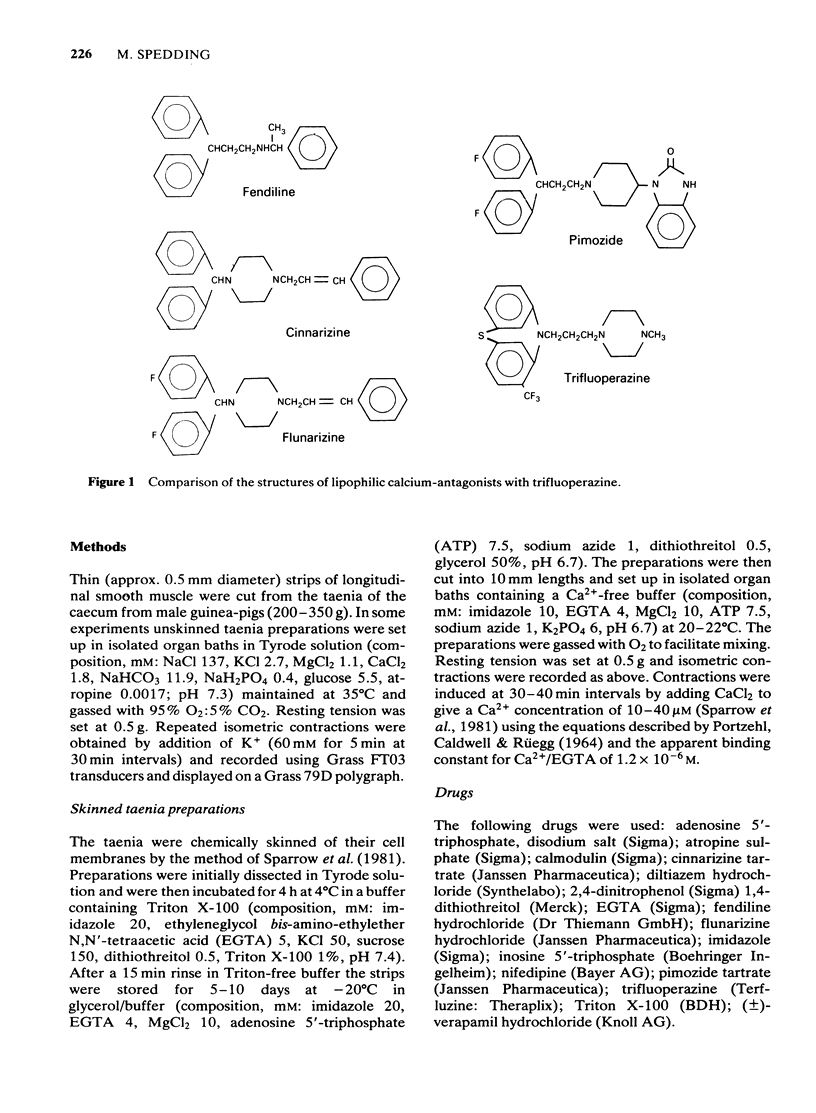

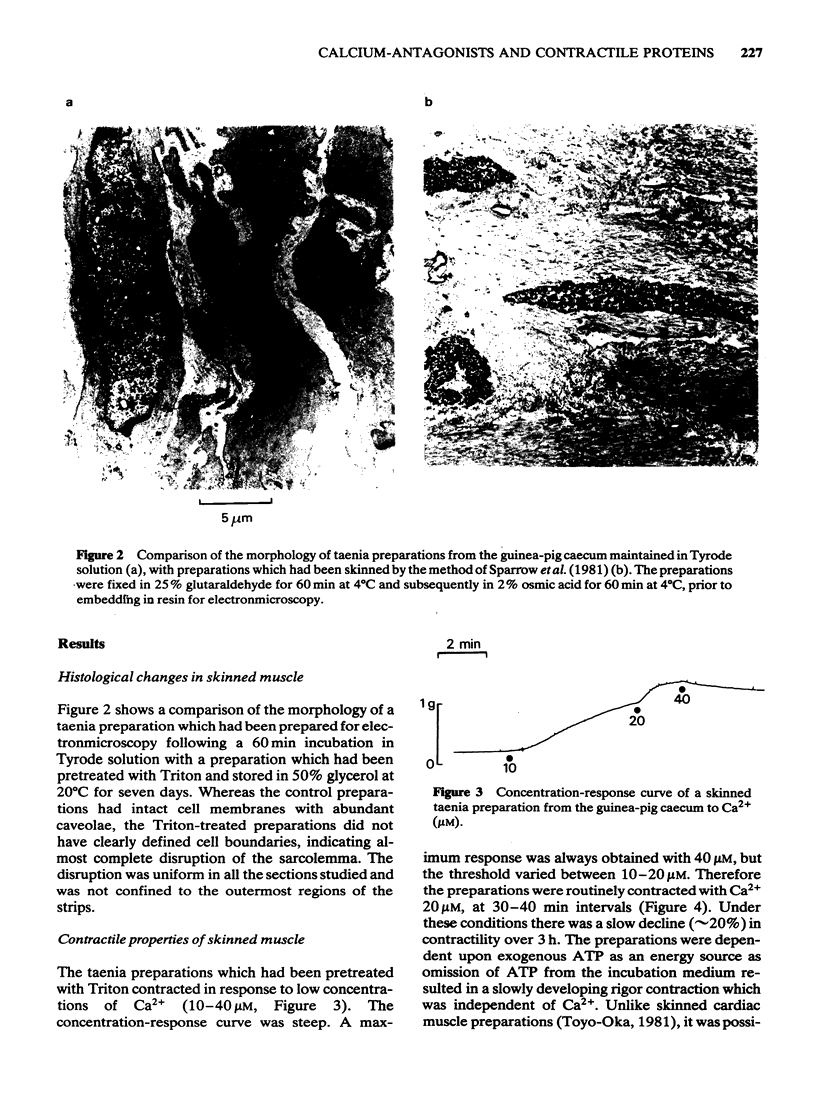

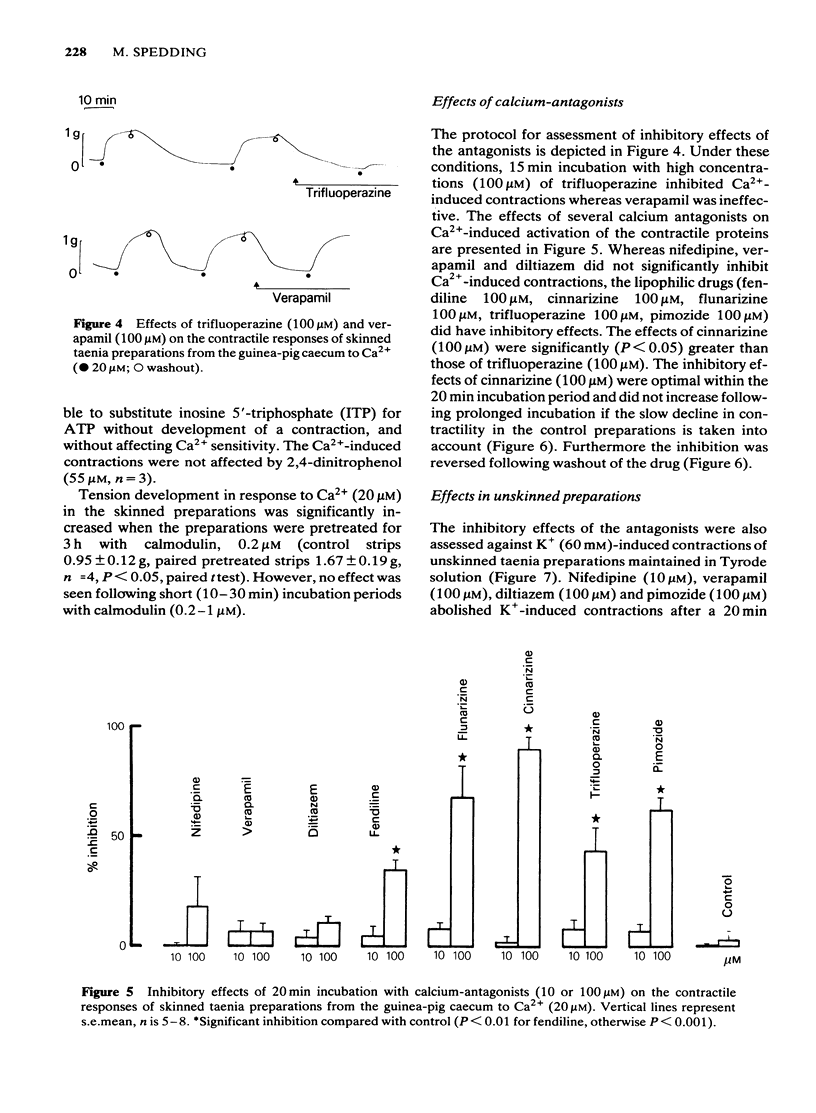

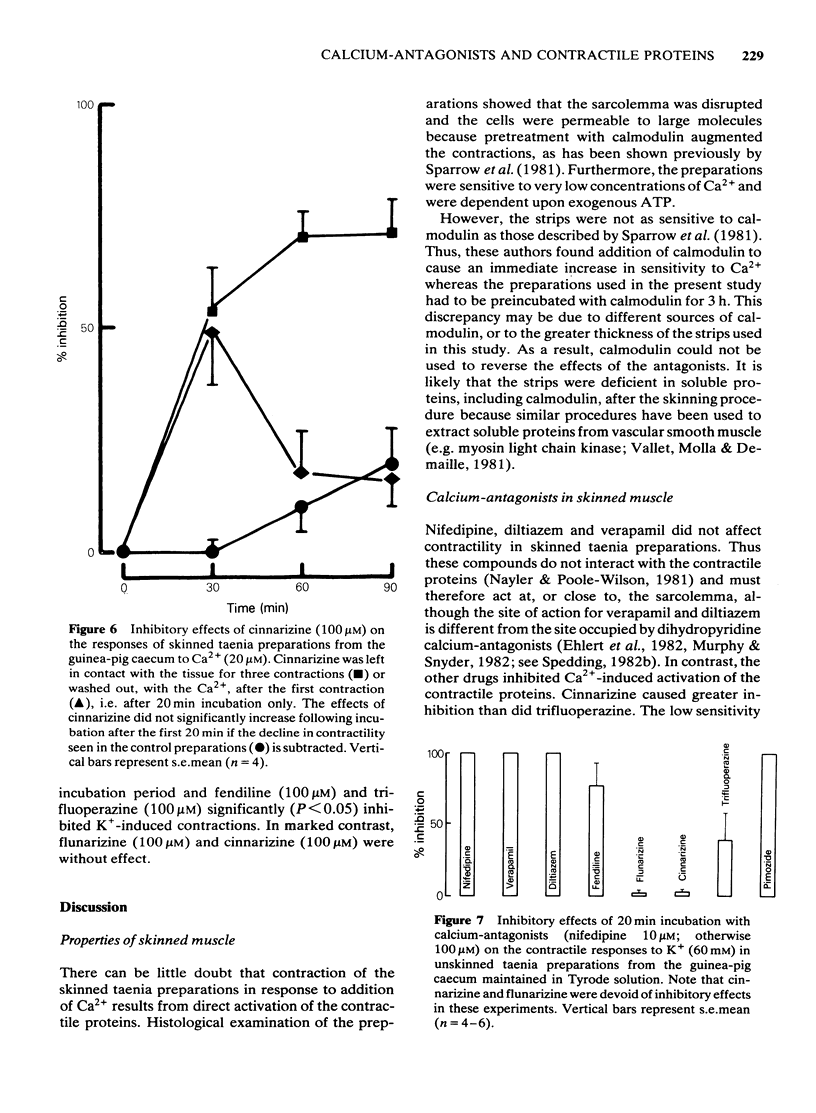

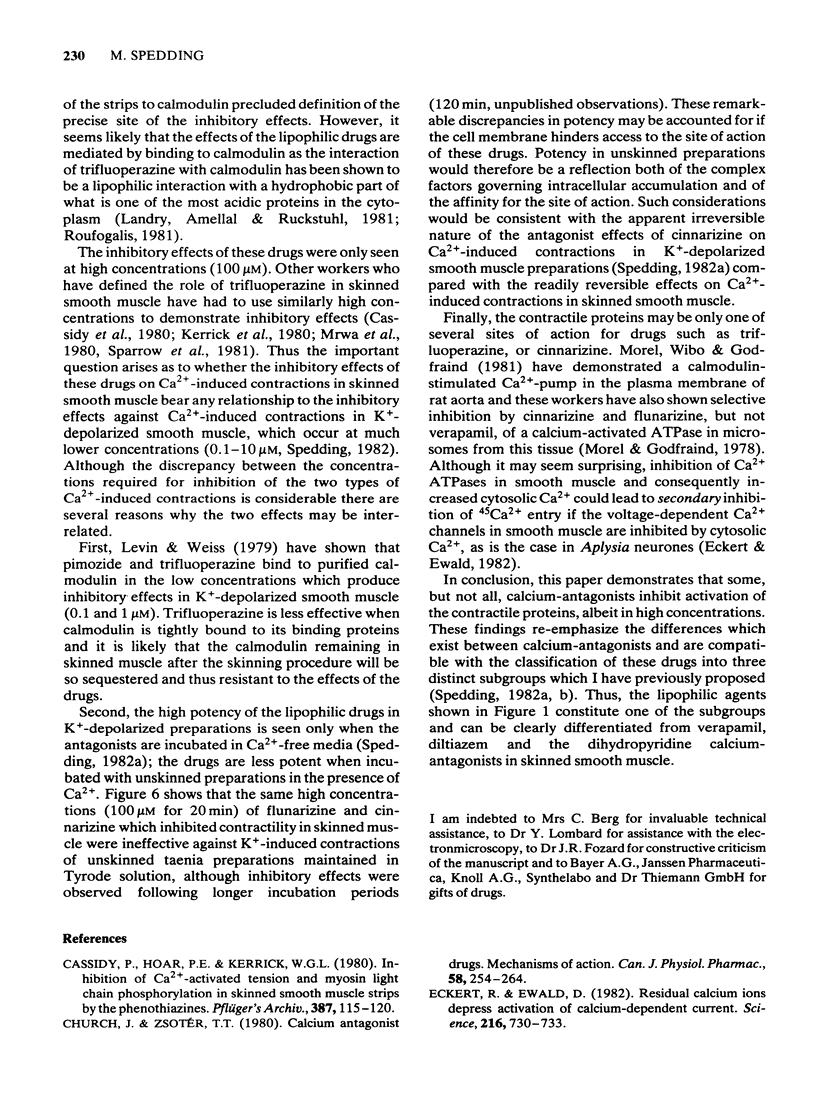

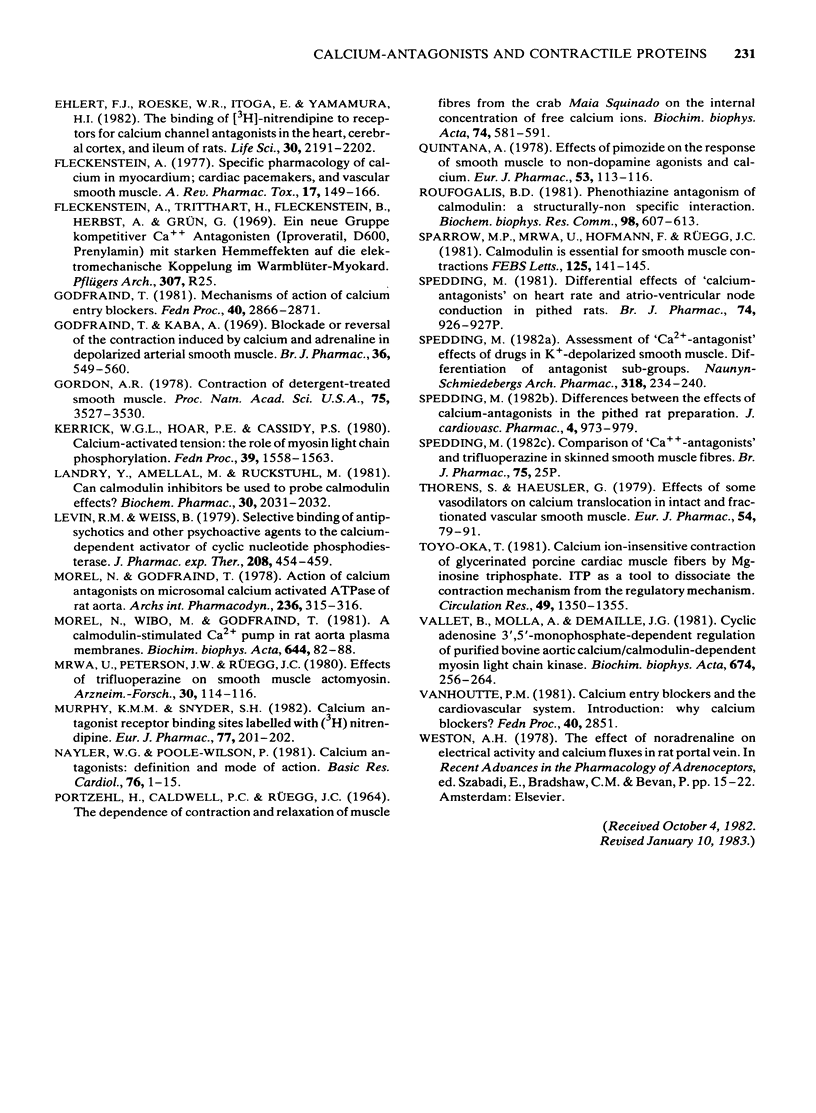

1 Taenia preparations from the guinea-pig caecum were treated with Triton X-100 and glycerol to disrupt the plasma membrane. Disruption of the sarcolemma was confirmed by electronmicroscopy. The preparations contracted in response to low concentration of Ca2+ (10-40 microM) and the contractions were dependent upon exogenous adenosine triphosphate (ATP). 2 Nifedipine (100 microM), verapamil (100 microM) and diltiazem (100 microM) did not inhibit Ca2+-induced activation of the contractile proteins. 3 In contrast, fendiline (100 microM), cinnarizine (100 microM), flunarizine (100 microM), pimozide (100 microM) and trifluoperazine (100 microM) significantly inhibited Ca2+-induced contractions. The effects of cinnarizine (100 microM) were reversible. 4 These findings disclose further differences between calcium-antagonists and suggest that certain of these agents have an intracellular site of action.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Cassidy P., Hoar P. E., Kerrick W. G. Inhibition of Ca2+-activated tension and myosin light chain phosphorylation in skinned smooth muscle strips by the phenothiazines. Pflugers Arch. 1980 Sep;387(2):115–120. doi: 10.1007/BF00584261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church J., Zsotér T. T. Calcium antagonistic drugs. Mechanism of action. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1980 Mar;58(3):254–264. doi: 10.1139/y80-044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert R., Ewald D. Residual calcium ions depress activation of calcium-dependent current. Science. 1982 May 14;216(4547):730–733. doi: 10.1126/science.6281880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlert F. J., Roeske W. R., Itoga E., Yamamura H. I. The binding of [3H]nitrendipine to receptors for calcium channel antagonists in the heart, cerebral cortex, and ileum of rats. Life Sci. 1982 Jun 21;30(25):2191–2202. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein A. Specific pharmacology of calcium in myocardium, cardiac pacemakers, and vascular smooth muscle. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1977;17:149–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.17.040177.001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfraind T., Kaba A. Blockade or reversal of the contraction induced by calcium and adrenaline in depolarized arterial smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 1969 Jul;36(3):549–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1969.tb08010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfraind T. Mechanisms of action of calcium entry blockers. Fed Proc. 1981 Dec;40(14):2866–2871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A. R. Contraction of detergent-treated smooth muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Jul;75(7):3527–3530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrick W. G., Hoar P. E., Cassidy P. S. Calcium-activated tension: the role of myosin light chain phosphorylation. Fed Proc. 1980 Apr;39(5):1558–1563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry Y., Amellal M., Ruckstuhl M. Can calmodulin inhibitors be used to probe calmodulin effects? Biochem Pharmacol. 1981 Jul 15;30(14):2031–2032. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(81)90217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin R. M., Weiss B. Selective binding of antipsychotics and other psychoactive agents to the calcium-dependent activator of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1979 Mar;208(3):454–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel N., Godfraind T. Action of calcium antagonists on microsomal calcium activated ATPase of rat aorta. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1978 Dec;236(2):315–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel N., Wibo M., Godfraind T. A calmodulin-stimulated Ca2+ pump in rat aorta plasma membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981 Jun 9;644(1):82–88. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(81)90061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrwa U., Peterson J. W., Rüegg J. C. Effects of trifluoperazine on smooth muscle actomyosin. Short communication. Arzneimittelforschung. 1980;30(1):114–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K. M., Snyder S. H. Calcium antagonist receptor binding sites labeled with [3H]nitrendipine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982 Jan 22;77(2-3):201–202. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(82)90021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayler W. G., Poole-Wilson P. Calcium antagonists: definition and mode of action. Basic Res Cardiol. 1981 Jan-Feb;76(1):1–15. doi: 10.1007/BF01908159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORTZEHL H., CALDWELL P. C., RUEEGG J. C. THE DEPENDENCE OF CONTRACTION AND RELAXATION OF MUSCLE FIBRES FROM THE CRAB MAIA SQUINADO ON THE INTERNAL CONCENTRATION OF FREE CALCIUM IONS. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1964 May 25;79:581–591. doi: 10.1016/0926-6577(64)90224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana A. Effects of pimozide on the response of smooth muscle to non-dopamine agonists and calcium. Eur J Pharmacol. 1978 Dec 15;53(1):113–116. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(78)90274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roufogalis B. D. Phenothiazine antagonism of calmodulin: a structurally-nonspecific interaction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981 Feb 12;98(3):607–613. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow M. P., Mrwa U., Hofmann F., Rüegg J. C. Calmodulin is essential for smooth muscle contraction. FEBS Lett. 1981 Mar 23;125(2):141–145. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80704-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spedding M. Assessment of "Ca2+ -antagonist" effects of drugs in K+ -depolarized smooth muscle. Differentiation of antagonist subgroups. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1982 Feb;318(3):234–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00500485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spedding M. Differences between the effects of calcium antagonists in the pithed rat preparation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1982 Nov-Dec;4(6):973–979. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198211000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorens S., Haeusler G. Effects of some vasodilators on calcium translocation in intact and fractionated vascular smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 1979 Feb 15;54(1-2):79–91. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(79)90410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyo-oka T. Calcium ion-insensitive contraction of glycerinated porcine cardiac muscle fibers by Mg-inosine triphosphate. ITP as a tool to dissociate the contraction mechanism from the regulatory mechanism. Circ Res. 1981 Dec;49(6):1350–1355. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.6.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet B., Molla A., Demaille J. G. Cyclic adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate-dependent regulation of purified bovine aortic calcium/calmodulin-dependent myosin light chain kinase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981 May 5;674(2):256–264. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(81)90383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]