Abstract

Hhex is required for early development of the liver. A null mutation of Hhex results in a failure to form the liver bud and embryonic lethality. Therefore, Hhex null mice are not informative as to whether this gene is required during later stages of hepatobiliary morphogenesis. To address this question, we derived Hhex conditional null mice using the Cre-loxP system and two different Cre transgenics (Foxa3-Cre, and Alfp-Cre). Deletion of Hhex in the hepatic diverticulum (Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/-) led to embryonic lethality, and resulted in a small and cystic liver with loss of Hnf4α and Hnf6 expression in early hepatoblasts. In addition, the gall bladder was absent and the extrahepatic bile duct could not be identified. Loss of Hhex in the embryonic liver (Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/-) caused irregular development of intrahepatic bile ducts and an absence of Hnf1β in many (cystic) biliary epithelial cells, which resulted in a slow, progressive form of polycystic liver disease in adult mice. Thus, we have shown that Hhex is required during multiple stages of hepatobiliary development. The altered expression of Hnf4α, Hnf6 and Hnf1β in Hhex conditional null mice suggests that Hhex is an essential component of the genetic networks regulating hepatoblast differentiation and intrahepatic bile duct morphogenesis.

Keywords: Hhex, Liver, Biliary tract, Extrahepatic bile duct, Polycystic liver disease

INTRODUCTION

The liver and biliary tract arise from the hepatic diverticulum, which develops as an out-pocketing of the ventral foregut endoderm around embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5) in mice (reviewed in Lemaigre and Zaret, 2004). For the most part, the cranial portion of the hepatic diverticulum gives rise to the liver and intrahepatic biliary tree while the caudal portion forms the extrahepatic biliary tract (Du Bois, 1963; Shiojiri, 1979). Early hepatoblasts in the diverticulum migrate into the surrounding mesenchyme and form the liver bud and cystic primordium (gall bladder precursor) by E10.5. Bipotential hepatoblasts within the liver bud eventually give rise to hepatocytes and biliary epithelial cells (BEC), which line the bile ducts (Shiojiri, 1979; reviewed in Shiojiri, 1997). BEC of the intrahepatic bile ducts (IHBD) originate from hepatoblasts surrounding branches of the portal vein within the embryonic liver (Shiojiri, 1979; Shiojiri, 1984). Development of IHBD occurs through a series of distinct stages including differentiation of BEC around E13.5, formation of the ductal plate by E15.5, and ductal plate remodeling that ends shortly after birth (Clotman et al., 2002). The ducts of the extrahepatic biliary tract are also lined by BEC, although development of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary systems occurs separately and apparently through different mechanisms. The extrahepatic biliary system forms by budding from the hepatic diverticulum in close association with the liver bud, and is composed of the gall bladder and several relatively large ducts, which converge to form the extrahepatic bile duct (EHBD) that connects the liver to the duodenum (Du Bois, 1963; Shiojiri, 1979).

The homeobox gene Hhex is expressed in the ventral foregut endoderm at E8.5 (Thomas et al., 1998; Bogue et al., 2000), and is required for very early development of the liver (Hallaq et al., 2004; Keng et al., 2000; Martinez-Barbera et al., 2000). In Hhex-/- mouse embryos, the hepatic diverticulum is specified in the foregut endoderm, but proliferation of cells in the diverticulum is reduced (Bort et al., 2004) and subsequent migration of early hepatoblasts into the surrounding mesenchyme fails to occur (Bort et al., 2006). As a result, the liver bud is absent in Hhex null embryos (Keng et al., 2000; Martinez-Barberra et al., 2000). In addition, Hhex mutants are lacking the cystic primordium, which has been attributed to defective movements within the foregut endoderm (Bort et al., 2004). Therefore, Hhex is essential for the delamination and migration of early hepatoblasts from the hepatic diverticulum in formation of the liver bud, and in the absence of Hhex hepatic development is arrested, after the specification stage, at E9.5.

The expression pattern of Hhex has also been described in hepatobiliary tissue during later stages of development. Hhex mRNA has been detected in the liver bud, the embryonic liver, the gall bladder and the extrahepatic bile duct (Thomas et al., 1998; Bogue et al., 2000). Furthermore, Hhex is expressed in the adult liver in hepatocytes and IHBD cells (Bogue et al., 2000; Keng et al., 1998), and Hhex has been shown to regulate the in-vitro expression of the ntcp gene (Denson et al., 2000), which encodes a bile acid transporter expressed in adult hepatocytes. These findings suggest that Hhex has important roles during later stages of hepatobiliary morphogenesis, which thus far have not been addressed using genetic means because of the very early arrest in liver and biliary tract development in Hhex-/- embryos.

In this study, we have developed a Hhex conditional null allele using the Cre-loxP system to determine the function of Hhex during later stages of liver and biliary tract development. We employed the Foxa3-Cre (Lee et al., 2005a; Lee et al., 2005b) and Alfp-Cre (Parviz et al., 2003) transgenes to eliminate Hhex in the hepatic endoderm at different developmental stages. Elimination of Hhex in the hepatic diverticulum (Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/-) resulted in a severely hypoplastic and cystic liver, with major defects in development of the extrahepatic biliary tract. The liver-enriched transcription factors (LETF’s) HNF4α and HNF6 were absent in hepatoblasts of Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos at E13.5, which resulted in major defects in hepatic epithelial development. Deletion of Hhex in the embryonic liver (Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/-) caused abnormal morphogenesis of IHBD, with a down-regulation of Hnf1β in many biliary epithelial cells, and polycystic liver disease in adult mutant mice. Our results show that Hhex is required in hepatobiliary development after liver bud formation, and that Hhex is essential for proper hepatoblast differentiation and bile duct development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Derivation of Hhexneoflox and Hhexflox alleles

To construct the targeting vector, a Hhex P1 genomic clone was isolated (Bogue et al., 2003). A loxP element was inserted in between XbaI and SpeI sites of the 3rd intron of a Hhex 3’ genomic fragment. An XhoI-BsaI 3’ Hhex fragment containing this loxP site insertion was blunt-end ligated into a BglII site in plasmid GR88 (from Trevor Williams, Univ. of Colorado Health Sciences Center). This plasmid contained a loxP site upstream of a neomycin resistance cassette flanked by FRT sites. Finally, a 3.8kb 5’ Hhex SnaBI-XhoI fragment was blunt-end ligated onto the above 3’ construct. The final targeting vector was sequenced in its entirety and used for the generation of Hhexneoflox ES cell clones by the Animal Genomics Services at the Yale School of Medicine according to standard procedures (Nagy et al., 2002). Mice used in this study were maintained on mixed backgrounds (129S1/Sv and C57Bl/6).

The Flp transgenic mouse (Rodriquez et al., 2000) was provided by the Animal Genomics Services at the Yale School of Medicine. The Hhexflox allele was cloned and sequenced to verify that the recombination event had occurred as designed.

Generation of Hhex conditional null mice

To derive our Hhex conditional null mice, Alfp-Cre (Parviz et al., 2003) and Foxa3-Cre (Lee et al., 2005a; 2005b) mice were bred onto our Hhex+/- background (Bogue et al., 2003). For almost all crosses, Cre;Hhex+/- mice were bred to our Hhexflox/+ or Hhexflox/flox mice. Embryos were staged according to Kaufman (1992). Hhex+/- and Hhexflox/- littermates were used as controls in comparison to Hhex conditional null mutants.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Embryos and adult liver tissue were processed for frozen and paraffin sectioning according to standard procedures (Nagy, et al., 2002). The antibodies used were as follows; rabbit anti-Hhex (Ghosh et al., 2000), rabbit anti-cytokeratin (DakoCytomation #Z0622), goat anti-HNF4α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology #SC-6556), rabbit anti-HNF6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology #SC-13050), and goat anti-HNF1β (Santa Cruz Biotechnology #SC7411). Immunohistochemistry on sections was performed using Antigen Unmasking Solution (H-3300; Vector Labs), Avidin/Biotin Blocking kit (SP-2001; Vector Labs), Vectastain ABC kit (PK-6100; Vector Labs), and the DAB peroxidase substrate kit (SK-4100; Vector Labs) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. For picro-sirius red staining, paraffin sections were cleared in xylene, rehydrated through an ethanol series, and rinsed in water. Slides were then placed in picro-sirius red solution (0.5 g Sirius red F3B in 500ml saturated aqueous picric acid; Sigma), for 1 hour at RT. Finally slides were washed twice in acetic acid water (5ml glacial acetic acid in 11ml distilled water), then dehydrated and cleared in xylene for mounting.

Immunofluorescence and Imaging

Immunofluorescence was performed according to standard procedures using Retrieve-All 2 (Signet Laboratories), Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-goat, Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-rabbit, and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit (Molecular Probes), Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes), and the Prolong Antifade kit (P-7481, Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Antibodies used were as follows; anti-Ki-67 antibody (BD Pharmingen, #556003), anti-human cytokeratin (DakoCytomation #A0575), and anti-HNF4α (Santa Cruz #SC-6556). All fluorescent images were captured on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M with an Axiocam MRm camera using Axiovision software and the ApoTome mode. Images are a ‘3-D’ representation of optical sections through approximately 3.5 microns of tissue.

RESULTS

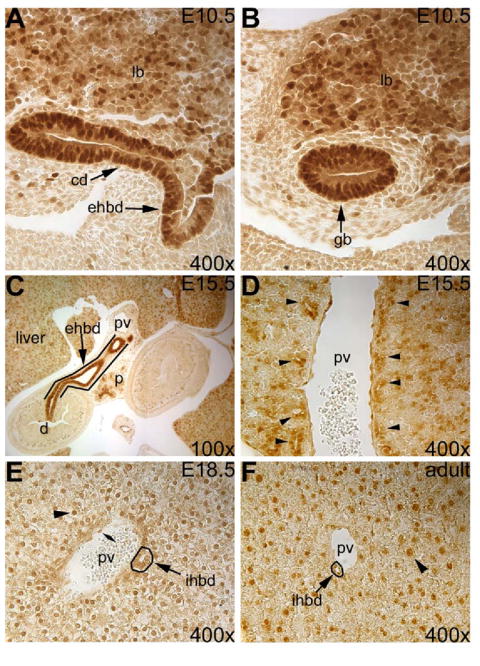

Hhex is expressed in hepatobiliary tissue throughout development

We have previously detected Hhex mRNA in BEC of the extrahepatic and intrahepatic biliary tract during embryogenesis and in the adult liver (Bogue et al 2000). To extend these results, we analyzed Hhex expression in the liver and biliary tract by immunohistochemistry using a polyclonal anti-Hhex antibody (Ghosh et al., 2000). At E10.5, Hhex is detected in hepatoblasts of the liver bud, and epithelial cells of the extrahepatic biliary tract precursors including the gall bladder primordia (Fig. 1A, B). At E15.5 Hhex was highly expressed in the extrahepatic bile duct (EHBD) epithelium (Fig. 1C) and in biliary cells of the ductal plate surrounding large branches of the portal vein near the liver hilum (Fig. 1D). Hhex was also detected in hepatocytes and biliary cells of the IHBD during late embryogenesis (Fig. 1E) and in the adult liver (Fig. 1F). Therefore, Hhex is expressed in the liver and biliary epithelium from the onset of hepatobiliary morphogenesis and into adulthood.

Fig. 1. Hhex immunostaining reveals expression in the liver and biliary epithelium throughout embryogenesis and in the adult.

(A) E10.5 Hhex expression in the liver bud (lb), the extrahepatic bile duct precursor (ehbd) and the cystic duct precursor (cd). (B) Hhex is detected in the gall bladder primordium (gb) at E10.5. (C) Hhex expression in the EHBD (outlined) at E15.5. (D) Hhex is also expressed in the biliary cells of the ductal plate (arrowheads) near the liver hilum. (E) Hhex is present in hepatocytes (arrowhead), intrahepatic bile duct cells (arrow), and endothelial cells (double arrowhead) at E18.5. (F) In the adult liver, Hhex is detected in hepatocytes (arrowhead) and biliary cells (arrow). ihbd=intrahepatic bile duct, d=duodenum, p=pancreas, pv=portal vein.

Derivation of a Hhex conditional null allele

To elucidate the role of Hhex in later stages of hepatobiliary development, we constructed a targeting vector to generate a Hhex conditional null allele using the Cre-loxP system (see Supplemental data, Fig. S1A). This construct was used to generate a targeted ES cell clone from which three chimeric founder males were obtained. Founder males were backcrossed to C57Bl/6 mice to derive the F1 generation of Hhexneoflox/+ mice. Genotyping of the Hhexneoflox/+ mice was performed by Southern and PCR (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Hhexneoflox/+ F1 mice were then used to derive the Hhex conditional allele (Hhexflox) after crossing to Flp/Flp transgenics (Rodriguez et al., 2000). This generated Flp;Hhexflox/+ F1 mice, which were then backcrossed one additional generation to C57Bl/6. These Hhexflox/+ F2 mice, and their progeny, were used for all further analysis, and genotyping was verified by Southern and PCR (Supplementary Fig. S1C). To confirm that the Hhexflox allele was functionally equivalent to the wild-type allele we intercrossed Hhexflox/+ mice. Hhexflox/flox pups were born at a normal Mendalian ratio and were healthy and fertile, indicating that the Hhexflox allele was functionally wild-type. Finally, we used PCR and sequencing to confirm the presence of the Hhexd2,3 allele in our Hhex conditional null mice after crossing the Hhexflox allele to Alfp-Cre mice (Supplementary Fig. S1D).

Hhex is essential for proper morphogenesis of the extrahepatic biliary tract

To test whether Hhex plays a role in the development of the extrahepatic biliary tract, we derived mutants in which Hhex was deleted in the hepatic diverticulum by crossing Hhexflox mice with the Foxa3-Cre transgene (Lee et al., 2005a) backcrossed to our Hhex+/- mice (Bogue et al., 1998). Foxa3-Cre has been shown to be active at E8.5 in ventral foregut endoderm, including the cells of the hepatic diverticulum (Lee et al., 2005a; Lee et al., 2005b). Thus, Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- (conditional null) mice should lack Hhex both in the liver bud and extrahepatic biliary tract primordia.

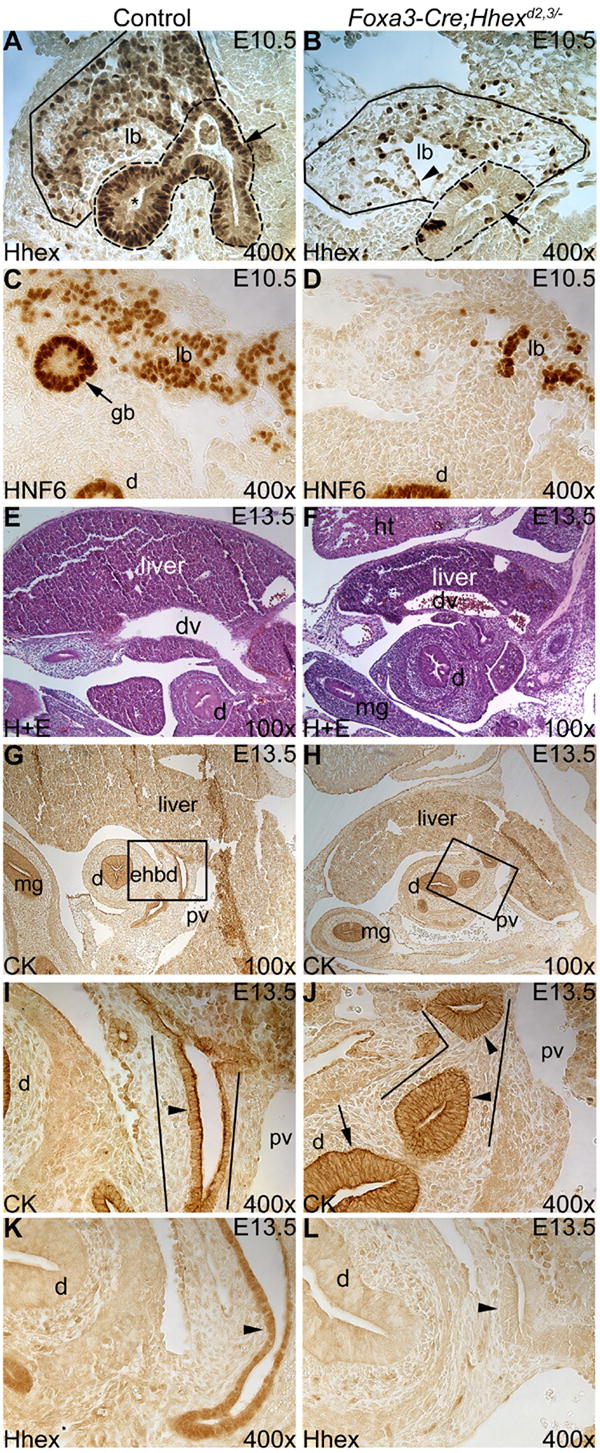

In Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos at E10.5, Hhex was absent in almost all endoderm-derived cells of the liver bud and extrahepatic biliary tract primordia (compare Fig. 2A and B). Expression of Hhex was unaffected in endothelial cells within the Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- liver confirming the deletion was specific to endoderm-derived cells (Fig. 2B). Therefore, Hhex was efficiently deleted in hepatobiliary tissue of mutant embryos by E10.5.

Fig. 2. Deletion of Hhex in the hepatic diverticulum in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutant embryos results in severe abnormalities in early development of the extrahepatic biliary tract.

(A,B) Hhex immunostaining at E10.5. (A) In the control, Hhex is detected in the liver bud (outlined in solid line) and extrahepatic biliary tract primordia (outlined in dashed line). The arrow marks the EHBD precursor epithelium and the asterisk labels the gall bladder primordium. (B) In the mutant, Hhex is efficiently deleted in the liver bud (outlined in solid line) and in the presumptive EHBD precursor (outlined in dashed lines). The arrow marks Hhex-negative cells in the EHBD precursor epithelium. The arrowhead labels an endothelial cell. (C,D) HNF6 immunostaining at E10.5. (C) HNF6 is normally expressed in the liver bud (lb) and gall bladder primordium (gb). (D) In the mutant, the gall bladder primordium is absent. (E,F) Hematoxylin and eosin (H+E) staining at E13.5. (E) Control liver. (F) The Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutant liver is hypoplastic compared to the control. (G-J) CK immunostaining at E13.5. (G) In the control, the EHBD (boxed region) is a duct extending ventro-caudal from the liver to the duodenum, and ventral to the main portal vein (pv). (H) In mutants, the EHBD could not be identified, and in its place were duct-like structures with abnormal epithelium. (I,J) Higher magnification of the boxed regions in E and F respectively. (I) Single cell layer cuboidal epithelium (arrowhead) lines the EHBD (outlined) in the control. (J) In Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos, abnormal duct-like structures (outlined) were mostly lined by a pseudostratified epithelium (arrowheads), similar to the duodenum (arrow). (K,L) Hhex immunostaining at E13.5. (K) Hhex is expressed in the EHBD epithelium in the control (arrowhead). (L) Hhex is absent from the abnormal duct-like structure, where the EHBD would normally form, in the mutant (arrowhead). Ventral is to the left and all sections are sagittal. mg=midgut, dv=ductous venosus, ht=heart.

Development of the extrahepatic biliary tract was severely perturbed in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos. The liver-enriched transcription factor HNF6 is normally detected in cells of the developing liver and in extrahepatic biliary tract precursors (Clotman et al., 2002; Pierreux et al., 2004). In control embryos at E10.5, HNF6 was expressed in the liver bud and gall bladder primordium (Fig. 2C) as previously described. However, the gall bladder primordium could not be identified in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos (Fig. 2D). In addition, few cells were HNF6-positive in the liver bud of mutant animals at this stage. At E13.5, the Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutant liver was hypoplastic compared to the control (compare Fig. 2E and F). Cytokeratin (CK) immunostaining revealed that development of the EHBD was also abnormal in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos. At E13.5 in controls, the EHBD forms just caudal to the liver and ventral to the main portal vein (Fig. 2G) and is lined by a single layer of columnar to cuboidal epithelial cells (Fig. 2I). In contrast, the EHBD appeared to be absent in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos (Fig. 2H), and the normal EHBD epithelium was replaced by pseudostratified epithelium resembling the duodenum (Fig. 2J). We verified that Hhex was absent in the abnormal, duct-like structure in the mutant by Hhex immunostaining (Fig. 2K,L).

Next we examined Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos at E16.5 to see how the EHBD phenotype progressed. At E16.5, the EHBD forms a prominent duct that passes ventrolaterally from the liver hilum to the duodenum adjacent to the portal vein and pancreas, and is lined by a single cell layer of columnar epithelium (Fig. 3A, C). In Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos, duodenal-like mucosa extended directly from the duodenum to the liver hilum (Fig. 3B, D). In addition, at the liver hilum, there appeared to be dilated hepatic ducts and biliary cysts lined by cuboidal epithelium (Fig. 3B). To confirm that this ectopic tissue was indeed duodenal epithelium, we performed HNF4α immunostaining. Hnf4α is expressed in the small intestine (Drewes et al., 1996), but not in BEC (Clotman et al., 2005). In control embryos, HNF4α was strongly expressed in the nucleus of epithelial cells lining the duodenum (Fig. 3E, G), with a very low level of expression in the epithelium lining the EHBD (Fig. 3G). In Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos, HNF4α was strongly expressed in the ectopic duodenal-like epithelial cells (Fig. 3F), with expression localized to the nucleus in these cells up to the liver hilum (Fig. 3H). This result indicated that ectopic duodenal tissue apparently replaced the EHBD in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants.

Fig. 3. The EHBD was replaced by duodenum in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos at E16.5.

(A-D) CK immunostaining. (A,B) Transverse sections near the liver hilum. (A) In the control, the arrow marks the cuboidal epithelium of the EHBD (outlined), and the arrowhead shows the large, broad villi of mucosa in the duodenum. (B) In Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants, duodenal-like epithelium is present at the liver hilum (arrowhead), and directly connects the duodenum to the liver (outlined). Double arrowhead indicates a presumptive dilated hepatic duct, and the arrow marks a biliary cyst within the liver. (C,D) Sagittal section planes near the hilum. (C) In the control, the arrow indicates the single-cell layer epithelium lining the EHBD (outlined). (D) In the mutant, outlines show the presumptive position of the EHBD, which contains mostly pseudostratified columnar epithelial cells with some single cell layer cuboidal epithelium where the duodenum is connected to the liver (arrowhead). (E-H) HNF4α immunostaining. (E) HNF4α is highly expressed in duodenal epithelium, but is essentially absent in the EHBD (outlined). (F) Abnormal, duodenal-like epithelium (HNF4α-positive) is outlined in the Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryo, and it extends from the duodenum up to the liver hilum. Arrowhead shows a dilated biliary duct within the liver. Arrow marks an abnormal duct within the liver with a pseudostratified epithelium that is positive for HNF4α. (G) In the control, strong nuclear HNF4α expression is detected in duodenal epithelium (arrow), and very weak expression is detected in the EHBD (arrowhead). (H) In the Hhex conditional null embryo, strong nuclear expression of HNF4α is detected up to the hilum (arrow), and the arrowhead shows weaker expression in abnormal epithelium within the liver. (I) HNF6 is normally expressed in the EHBD epithelium, but not in the duodenum. (J) In mutants, HNF6 is absent in the ectopic duodenal tissue (arrow), but is detected in some epithelial cells at the base of the liver (arrowhead). These cells probably represent hepatic duct epithelia or a remnant of the EHBD. Ventral is to the left. e=esophagus.

In Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos, single cell layer columnar/cuboidal epithelia was detected where the duodenum fused to the liver, suggesting the presence of biliary epithelia. Therefore, we examined the expression of HNF6, which is expressed in biliary epithelia but not duodenal epithelia (Fig. 3I). In Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos, almost all of the ectopic duodenal tissue did not express HNF6, but some epithelial cells near the base of the liver were positive for HNF6 (Fig. 3J). These HNF6 positive cells most likely represent either hepatic duct epithelium or a remnant of the EHBD. We conclude that in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos, the EHBD is mostly or completely replaced by duodenum.

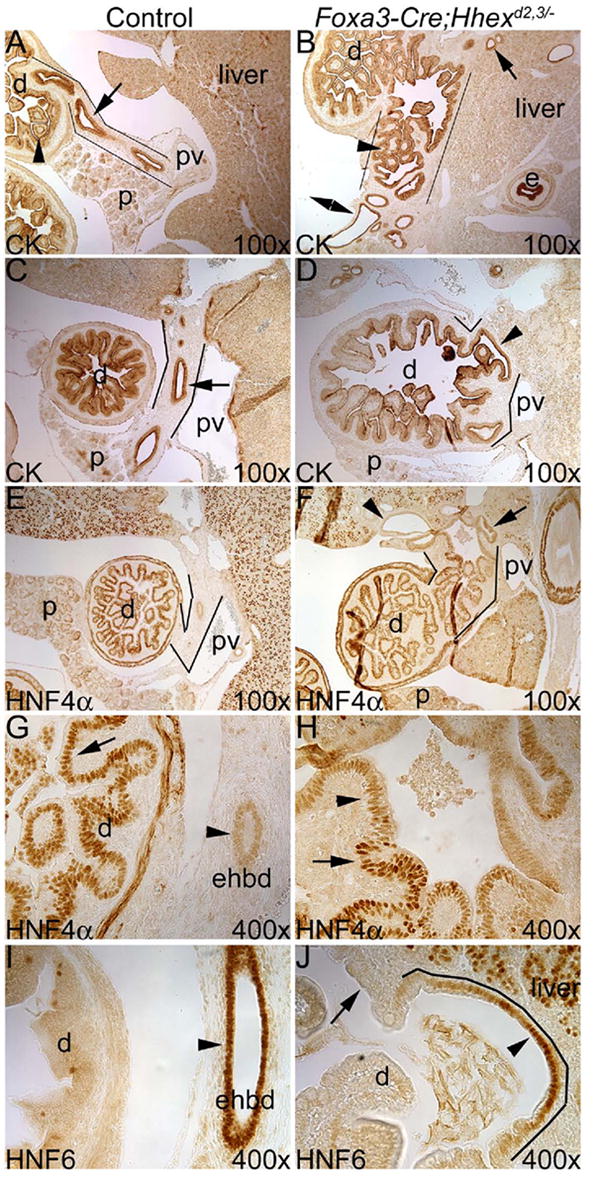

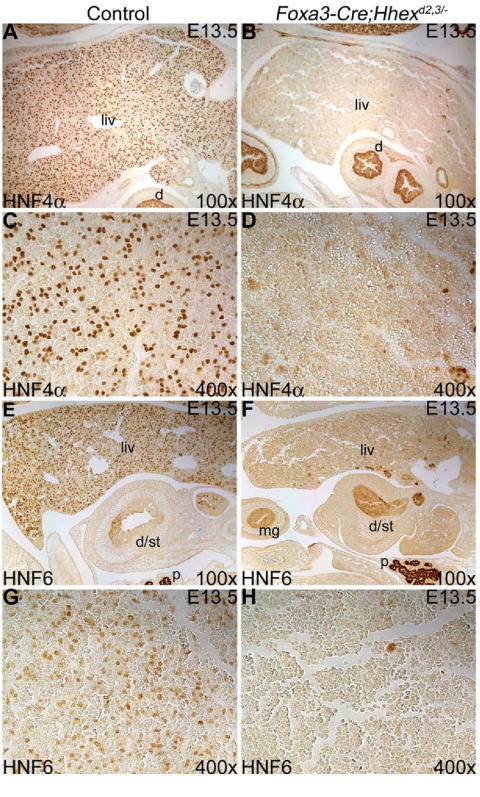

Hhex is required for normal hepatoblast differentiation

Deletion of Hhex in the hepatic diverticulum was embryonic lethal and resulted in a severely hypoplastic liver in all Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants analyzed. We examined expression of Hnf4α (Fig. 4A-D), which is a marker for the hepatoblast in the early embryonic liver and is required for normal differentiation of hepatocytes (Parviz et al., 2003; Battle et al., 2006). In control embryos at E13.5, HNF4α was detected in hepatoblasts as expected (Fig. 4A, C). However, in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos, HNF4α was absent from almost all hepatic cells (Fig. 4B, D). A similar result was seen for the Onecut transcription factor HNF6 (Fig. 4E-H), which is required for proper hepatoblast differentiation and bile duct development (Clotman et al., 2002). Interestingly, by E16.5 HNF4α and HNF6 were detected in many parenchymal cells in the liver of Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos, although a large number of hepatic cells were still negative (data not shown). These results suggest that Hhex is required for the expression of Hnf4α and Hnf6 only during the early stages of hepatogenesis, and that loss of expression of these LETF’s in early hepatoblasts of Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants may lead to a disruption of normal hepatic architecture later in development.

Fig. 4. Deletion of Hhex in the hepatic diverticulum resulted in an early loss of HNF4α and HNF6 expression in the Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutant liver.

(A-D) HNF4α immunostaining at E13.5. (A) HNF4α expression in hepatoblasts of the control liver (liv). (B) HNF4α is absent in cells of the Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutant liver. (C,D) Higher magnifications of control and mutant livers, respectively. (E-H) HNF6 immunostaining at E13.5. (E) HNF6 is expressed in hepatoblasts of the control liver. (F) In the Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutant, HNF6 is absent in almost all hepatic cells. d/st=rostral duodenum/caudal stomach. (G,H) Higher magnifications of control and mutant livers, respectively. Ventral is to the left in A, B, E and F.

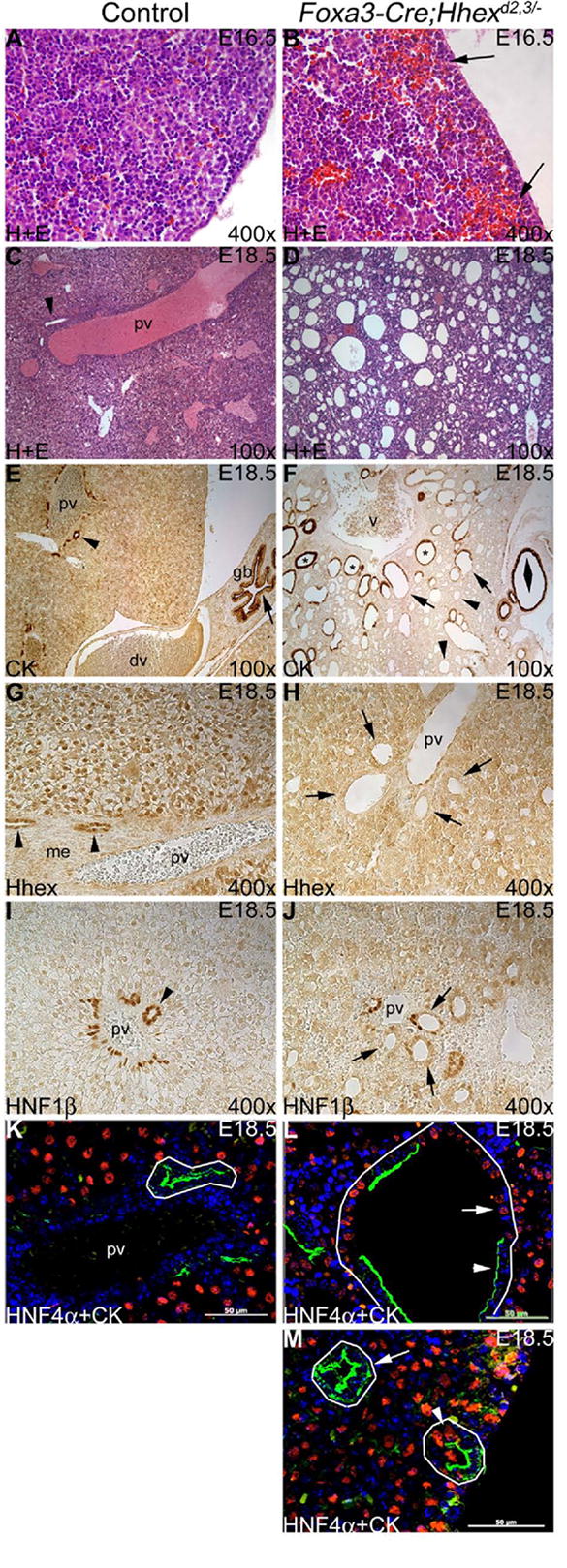

By E16.5-E18.5, Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- livers were grossly abnormal compared to controls. At E16.5, in the mutant, tissue at the ventral liver periphery had lost its cohesive structure and this resulted in a trapping or pooling of blood cells in this region (compare Fig. 5A and B). At E18.5, normal hepatic tissue morphology is characterized by numerous portal vein branches associated with IHBD (Fig. 5C). However, in severely affected mutants, normal hepatic architecture was disrupted and mutant livers were extremely cystic with large dilated duct-like structures and many smaller cysts (Fig. 5D). We examined these duct-like structures and cysts in greater detail to determine their cellular origin. In controls, immunostaining with a biliary-specific CK antibody showed that only BEC were strongly positive for CK (Fig. 5E). In Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutant embryos, many duct-like structures/cysts stained positive for biliary CK (Fig. 5F). The larger CK-positive duct-like structures probably represent dilated hepatic ducts, and other structures most likely represent dilated IHBD or biliary cysts. However, some duct-like structures/cysts had a heterogeneous epithelium with both CK-positive and CK-negative cells, whereas other cysts were composed entirely of cells that were CK-negative. To confirm that the heterogeneous cystic epithelium in mutants was not due to incomplete deletion of Hhex in these cells, we performed Hhex immunostaining at E18.5 (Fig. 5G, H). In Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants, Hhex was absent in parenchymal cells and cystic epithelial cells in the liver. HNF1β is a LETF expressed in biliary epithelia (Fig. 5I) and required in IHBD morphogenesis (Coffinier et al., 2002). However, in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants, HNF1β was absent in many cystic biliary epithelial cells (Fig. 5J). Dual immunolabeling for CK and HNF4α confirmed that IHBD cells are normally CK-positive and HNF4α-negative (Fig. 5K). In contrast, some duct-like structures/cysts in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- livers contained both CK-positive cells and HNF4α-positive cells (Fig. 5L). Although there was variability in the severity of cystogenesis in mutant embryos, mildly affected mutants also displayed a similarly abnormal hepatic epithelia as severely affected embryos. Some ‘hybrid’ cells that were both CK-positive and HNF4α-positive were detected and many cysts formed in the absence of a branch of the portal vein, suggesting the normal mechanism of BEC induction is not properly functioning in this mutant (Fig. 5M). In mutants, hepatocytes remained small and tightly clustered, suggesting a failure to differentiate normally. Therefore, we conclude that the absence of Hhex in the Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- liver primordium results in abnormal hepatoblast differentiation and severely abnormal hepatic architecture by late embryogenesis, most likely due to the loss of HNF4α and HNF6 expression in the early embryonic liver.

Fig. 5. The Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutant liver is severely abnormal by late embryogenesis.

(A-D) Hematoxylin and eosin (H+E) staining at E16.5 (A,B) and E18.5 (C,D). (A) Control ventral liver periphery. (B) Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutant ventral liver periphery showing loss of cohesive structure and trapping of blood cells (arrows). (C) A large branch of the portal vein is shown with an IHBD (arrowhead) in the control liver. (D) Severe Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutant liver phenotype. The mutant liver was severely cystic, and hepatic architecture appeared grossly abnormal. (E,F) CK immunostaining at E18.5. (E) Biliary epithelia of the IHBD (arrowhead) and the gall bladder (arrow) are strongly positive for CK. (F) Severe Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutant liver phenotype. Mutant livers had duct-like structures/cysts lined by CK-positive cells (asterisks), CK-negative cells (arrowheads), and both CK-positive and CK-negative cells (arrows). The large biliary cyst on the right (double arrowhead) is probably derived from cystic duct epithelium. V=presumptive junction of inferior vena cava and main portal vein. Ventral is to the right in E and F. (G,H) Hhex immunostaining at E18.5. (G) Hhex is expressed in biliary cells of IHBD (arrowheads) and in hepatocytes in controls. me=periportal mesenchyme. (H) Hhex is absent in cystic biliary epithelia (arrows) and in hepatocytes in the mutant. (I,J) HNF1β immunostaining at E18.5. (I) In the control, HNF1β is expressed in biliary cells of intrahepatic bile ducts (arrowhead). (J) In the mutant, HNF1β is absent or weakly expressed in most cystic cells (arrows). (K-M) HNF4α (red) + CK (green) dual immunofluorescence at E18.5. (K) In the control, IHBD cells (outlined) are CK-positive and HNF4α-negative. (L,M) Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants. (L) Severe mutant phenotype. A large duct-like structure/cyst (outlined) containing both CK-positive cells (arrowhead) and HNF4α-positive cells (arrow). (M) Biliary cysts (arrow) are detected in the absence of the portal vein, and some hybrid cells (both HNF4α-positive and CK-positive) were also detected in cysts (arrowhead). Hepatocytes (HNF4α-positive) remain small and tightly clustered (compare to control in K). Scale bar=50um.

Hhex is required for proper development of the intrahepatic bile ducts

To determine if Hhex has an essential role in liver development during late embryogenesis, we used Alfp-Cre transgenic mice (Zhang et al., 2005; Krupczak-Hollis et al., 2004; Parviz et al., 2003). Previous studies have shown that Alfp-Cre provides deletion of a floxed allele in the liver by E15 (Krupczak-Hollis et al., 2004; Parviz et al., 2003). We generated Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- (conditional null) mice by crossing our Hhexflox mice to Alfp-Cre;Hhex+/- mice.

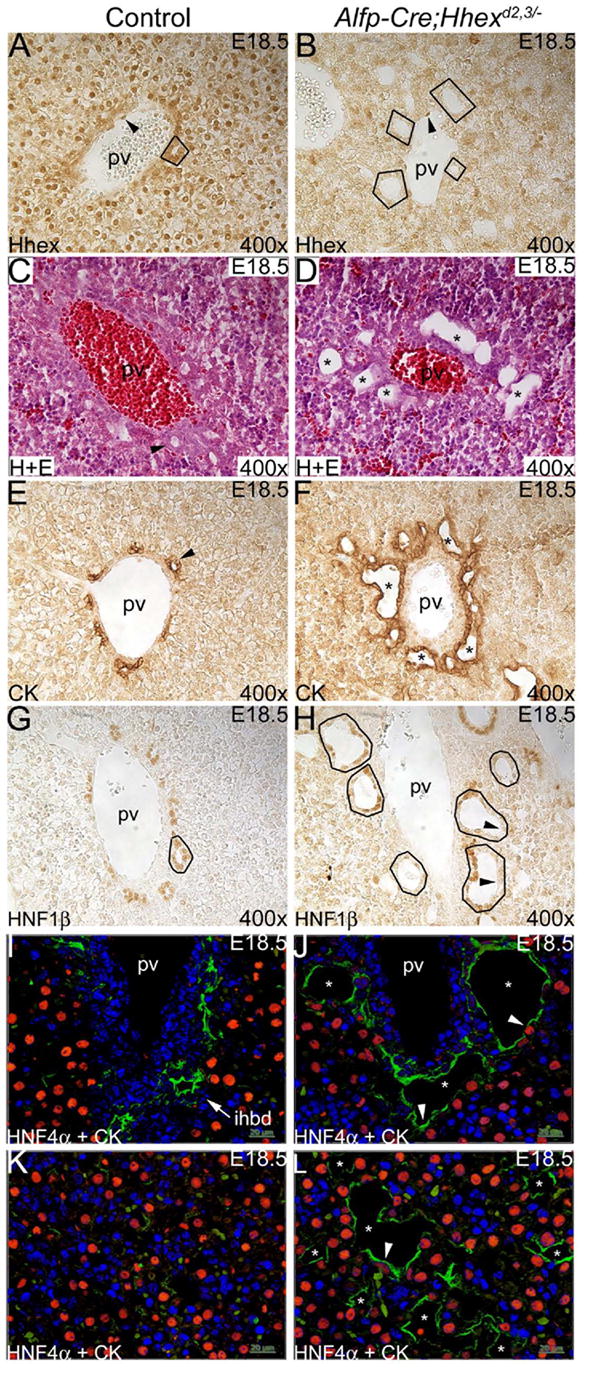

To assess the extent of deletion of Hhex in Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- livers, we performed Hhex immunohistochemistry. In controls at E18.5, Hhex was detected in the liver in hepatocytes, IHBD, and endothelial cells (Fig. 6A). In Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos, Hhex was absent in hepatocytes and biliary cells as expected (Fig. 6B). Deletion of Hhex in the Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- liver was also confirmed by real-time RT-PCR (data not shown).

Fig. 6. Hhex is required for the proper development of intrahepatic bile ducts.

(A,B) Hhex immunostaining on liver sections at E18.5. (A) In controls, Hhex was detected in hepatocytes, biliary epithelial cells of the IHBD (outlined), and endothelial cells (arrowhead). (B) In Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants, Hhex was not detected in liver parenchyma or BEC (outlined), but Hhex was detected in endothelial cells (arrowhead). (C,D) H+E staining. (C) Control portal vein with IHBD precursor (arrowhead). (D) Mutant portal vein with abnormal duct-like structures/cysts (asterisks). (E,F) CK immunostaining. (E) In controls, portal veins were associated with one or two CK-positive IHBD (arrowhead). (F) In mutants, portal veins were surrounded by many CK-positive cysts and duct-like structures (asterisks). (G,H) HNF1β immunostaining. (G) In the control, HNF1β was detected in biliary cells of IHBD (outlined). (H) In Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants, some cysts had many cells that were HNF1β-negative. (I-L) HNF4α and CK dual-label immunofluoresence. (I) In controls, IHBD cells are CK-positive and HNF4α-negative (arrow). (J) In mutants, many cystic CK-positive cells were also HNF4α-positive (arrowheads). (K) In controls, parenchymal tissue is composed mainly of HNF4α-positive hepatocytes. (L) In mutants, cysts (asterisks) with hybrid cells (arrowhead) were present throughout the liver.

We examined Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- livers at E18.5 for abnormal epithelial morphology. Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed that portal vein branches in mutants were surrounded by abnormal duct-like structures/cysts (compare Fig. 6C and D). Staining with the biliary CK antibody showed that control portal tracts had a normal pattern of a few scattered CK-positive cells around the portal vein, with one or two IHBD precursors (Fig. 6E). However, portal tracts in Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- livers were often surrounded by many irregular biliary duct-like structures/cysts (Fig. 6F). HNF1β immunostaining of Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- livers showed that, in severely affected mutants, this transcription factor was absent in many cystic biliary epithelial cells (compare Fig. 6G and H). Also, hybrid cells (both HNF4α- and CK-positive) were present in duct-like structures/cysts surrounding portal veins, and these hybrid cells were not detected in control IHBD (compare Fig. 6I and J). Finally, in mutants, many of the cysts present throughout the parenchymal tissue appeared to form in the absence of a branch of the portal vein (compare Fig. 6K and L). The irregular duct-like structures/cysts in Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants is characteristic of a ductal plate malformation (DPM) and this suggests that Hhex plays a role in ductal plate remodeling and/or in the regulation of periportal cell differentiation.

Deletion of Hhex in the embryonic liver results in a slow, progressive form of polycystic liver disease

In contrast to deletion of Hhex in the hepatic diverticulum in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos, which was embryonic lethal, deletion of Hhex in the embryonic liver in Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mice was not lethal. Genotyping showed that in crosses between Hhexflox/+ mice and Alfp-Cre;Hhex+/- mice, 14 out of 89 pups were Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- (16% actual, 12.5% expected).

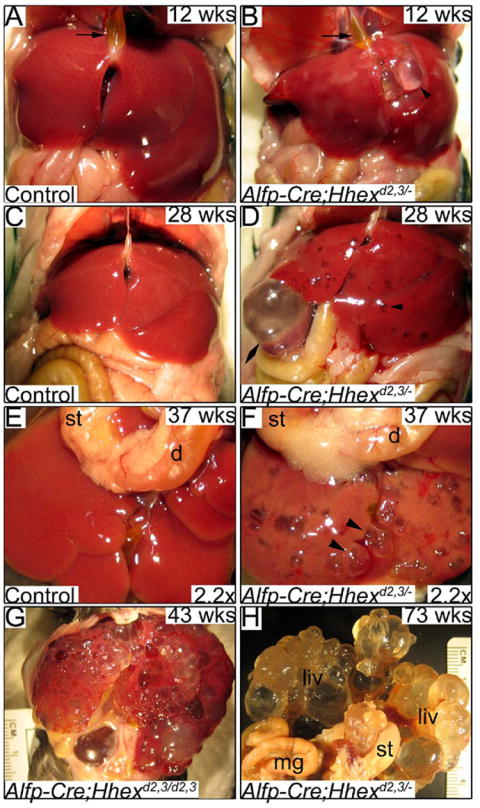

We examined livers in mice from 8 weeks to 73 weeks of age. Hepatic cysts were visible on the surface of the liver in 24 out of 26 Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mice, while none of the control mice examined had cysts (Fig. 7A-F). Analysis of four 8 week old mice revealed that the most severely affected liver had >50 visible hepatic cysts. The three other Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- livers that were examined at this age had >29, >25, and >16 visible hepatic cysts. Many cysts were multiloculated and almost all cysts contained a clear fluid (Fig. 7B). Hepatic cysts visible at the liver surface ranged in size from approximately 0.5mm to 8mm in diameter. The largest cyst identified was approximately 8mm × 8mm × 15mm (Fig. 7D). Cysts were seen in all lobes of the liver, and were common near the ventral midline and periphery (Fig. 7F). There was some variability in the severity of the liver phenotypes among the different age groups. However, the severity of cystogenesis tended to be worse in older mutant animals. Most mutant mice examined around 1 year of age and older had severe polycystic liver disease (Fig. 7G, H).

Fig. 7. Deletion of Hhex in the embryonic liver results in polycystic liver disease in adult mice.

(A,B) Ventral views of livers at 12 weeks of age. (A) Control liver and gall bladder filled with bile (arrow). (B) Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutant liver and gall bladder filled with bile (arrow). Arrowhead indicates a large hepatic cyst filled with a clear fluid. (C,D) Ventral views of livers at 28 weeks of age. (C) Control liver. (D) Numerous cysts are obvious throughout the liver (arrowhead). Double arrowhead shows an extremely large hepatic cyst. (E,F) Ventro-caudal views of dissected livers at 37 weeks of age. (E) Control liver. (F) The Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- liver has many large, multi-loculated cysts (arrowheads) and some discoloration, probably due to fibrosis. (G) A mutant liver at 43 weeks of age with severe cystic disease. (F) Ventro-caudal view of a mutant liver (fixed) at 73 weeks of age, which is almost completely cystic. st=stomach, d=duodenum.

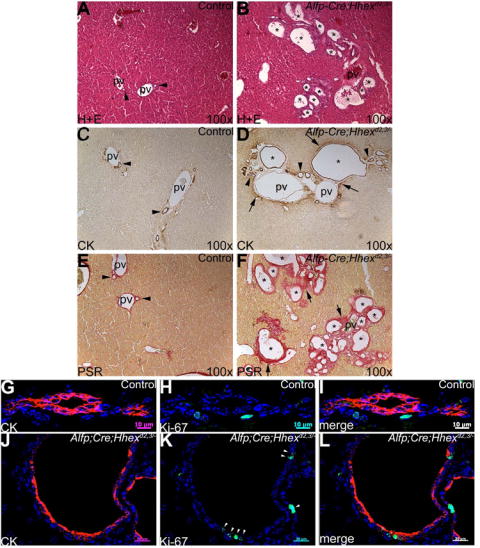

In human polycystic liver disease, hepatic cysts arise from BEC and are associated with defects in the development of IHBD. Histological analysis of adult Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- livers revealed severe abnormalities in IHBD morphogenesis. Normally, only one or two IHBD form near each branch of the portal vein (Fig. 8A). In Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- livers, portal veins were surrounded by multiple cysts and irregular duct-like structures (Fig. 8B), most lined by a single layer of cuboidal or flattened epithelium (data not shown), suggesting that the cysts were of biliary cell origin. In addition, no red blood cells were detected in cysts examined by H+E staining at 8 weeks of age (data not shown), confirming that these cysts were not vascular structures.

Fig. 8. Hhex is required for proper morphogenesis of intrahepatic bile ducts.

Histology and immunostaining on liver sections from mice at 28 weeks of age. (A,B) H+E staining. (A) In controls, portal veins are generally associated with one or two IHBD (arrowheads). (B) In Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3./- mutants, portal veins are surrounded by multiple duct-like structures/cysts (asterisks). (C,D) CK immunohistochemistry. (C) CK expression is normally confined to biliary epithelial cells lining the IHBD in the periportal region (arrowheads). (D) Asterisks show large CK-positive biliary cysts surrounding a branch of the portal vein in the mutant. Arrowheads show multiple smaller ducts/cysts in the periportal region. Arrows show an up-regulation of biliary-specific CK in periportal cells. (E,F) Picro-sirius red staining for collagen. (E) In controls, a relatively thin layer of collagen (red staining) surrounds the IHBD (arrowheads) and portal veins. (F) In mutants, extensive collagen deposition (arrows) was detected around cysts (asterisks) and portal veins. (G-L) Dual-label immunofluoresence for CK (red) and Ki-67 (green). (G-I) Control IHBD. (G) CK positive BEC. (H) In general, BEC are normally Ki-67-negative. (I) Merged image of G and H. Scale bar is 10um. (J-L) Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- cyst epithelia. (J) Cystic epithelia are CK-positive. (K) Many cells lining cysts are Ki-67-positive (arrowheads). (L) Merged image of J and K. Scale bar is 20um.

To verify that the cysts found in Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- livers were biliary in origin, we performed immunohistochemistry using the biliary CK antibody. In control livers, CK staining is confined to cells lining the IHBD (Fig. 8C), and is absent in periportal hepatocytes. In Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- livers, portal veins were often surrounded by large CK-positive biliary cysts, and many smaller CK positive cysts, ducts, or ductal plate remnants (Fig. 8D). The abnormal expression of biliary-specific CK was also detected in some periportal cells. To examine these cysts further, we performed a histological stain for collagen. Bile ducts and portal veins are normally incorporated into a collagen-rich extracellular matrix. A relatively thin layer of collagen positive periportal mesenchyme surrounded portal veins and IHBD in controls (Fig. 8E). In severely affected Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- livers, portal tracts and cysts were surrounded by an extensive layer of collagen deposition (Fig. 8F). From these results, we conclude that hepatic cysts in Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mice are lined by biliary cells and are a result of abnormal morphogenesis of IHBD.

In polycystic disease, cystic epithelial cells have an increased rate of proliferation when compared to normal epithelia (Gregoire et al., 1987; reviewed in Alvaro et al., 2006). In fact, normal biliary cells of IHBD have been described as postmitotic (Fabris et al., 2000). We examined control bile ducts and Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- cystic epithelia by dual-label immunofluorescence for the expression of the proliferation marker Ki-67 and biliary CK. In control mice, we found that only 2.3% (n=395) of CK-positive cells were also positive for Ki-67 (Fig. 8G-I). However, cystic biliary epithelia in mutant mice had a greater than four-fold higher rate of proliferation (9.6%, n=707; Fig. 8J-L) than normal biliary cells and this was a statistically significant difference (Student’s T-test: P < 0.05). Therefore, abnormal proliferation of cystic biliary epithelial cells in Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants may contribute to the progression of cystogenesis in these mice.

DISCUSSION

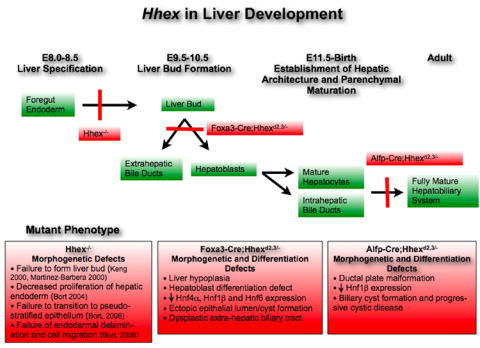

Hhex has previously been shown to be essential in formation of the liver primordium in mouse. In Hhex-/- mutant embryos, liver specification occurs but the liver bud fails to form (Keng et al., 2000; Martinez-Barbera et al., 2000). Hhex appears to be important for early ventral endodermal proliferation because in Hhex-/- embryos, endodermal cells of the ventral-lateral foregut have a reduced rate of proliferation (Bort et al., 2004). As well, cells of the hepatic diverticulum in Hhex-/- embryos fail to breakdown laminin and delaminate into the surrounding mesenchyme and this is associated with a defect in interkinetic nuclear migration and a failure in the conversion of the hepatic endoderm to a pseudostratified epithelium (Bort et al., 2006). Hhex is also required for budding of the cystic primordium and ventral pancreas (Bort et al., 2004; Bort et al., 2006). We have shown here that Hhex is expressed in hepatobiliary tissue throughout embryogenesis and in the adult. To overcome the very early arrest in hepatobiliary development in the Hhex-/- embryos, we have derived Hhex conditional null mice using the Cre-loxP system, allowing us to address the roles of Hhex in later stages of liver and biliary development. We have shown, for the first time, that Hhex is required for hepatic differentiation and morphogenesis after liver bud formation. A summary of the differences between the Hhex-/-, Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/-, and Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutant phenotypes is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Summary of the effects of Hhex deletion at different stages of liver development.

The stages of liver development are noted across the top with the tissues/cell types that express Hhex noted in green boxes. The consequences of Hhex deletion as well as the specific Hhex-deleted mouse strain are noted and summarized in the red boxes.

Hhex is necessary for the proper morphogenesis of the extrahepatic biliary tract

Hhex is expressed in the epithelium of the extrahepatic biliary tract, including the EHBD and gall bladder, from E10.5 through late embryogenesis. Deletion of Hhex in the hepatic diverticulum of Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants resulted in the absence of the gall bladder and replacement of the EHBD by duodenum. In some Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants there was a large ventral midline cystic structure, which is most likely derived from cystic duct epithelium, rather than gall bladder epithelium, because we could not identify the gall bladder primordium at E10.5 by HNF6 immunostaining. In no case was a well-defined gall bladder ever found in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants at E18.5. The replacement of the EHBD by duodenum may result from an arrest in development, or a change in cell fate. Interestingly, it was recently suggested that Hhex has an important role in the epithelial transformation of ventral foregut endoderm cells (Bort et al., 2006). We speculate that, in the absence of Hhex, most cells in the caudal hepatic diverticulum that are normally fated to form the EHBD instead become duodenal cells. This hypothesis is supported by several lines of evidence. In Hhex-/- mutant embryos, it has been suggested that cells of the hepatic diverticulum take on characteristics of duodenal cells at E10.5 because they ectopically express gata4 and shh (Bort et al., 2006). In addition, the EHBD, duodenum, and pancreas normally develop from adjacent regions of the foregut endoderm, and it has previously been shown that this part of the endoderm retains some plasticity during development (Fukuda et al., 2006; Sumazaki et al., 2004; Offield et al., 1996). However, cell lineage analysis will be necessary to confirm a change in cell fate of hepatic endoderm cells in Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants. The observation of HNF6-positive epithelial cells at the base of the mutant liver, and in direct contact with duodenal epithelium, could suggest a remnant of the proximal EHBD. Therefore, Hhex may normally function to suppress the duodenal differentiation program in the cells that give rise to more distal portions of the EHBD. It is interesting to note that the role of Hhex in EHBD development appears to be conserved, because in a Hhex morphant in zebrafish the EHBD could not be identified (Wallace et al., 2001).

Hhex is required in the early embryonic liver for normal hepatoblast differentiation

Our work strongly suggests that Hhex is essential in the proper differentiation of hepatoblasts. In Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- embryos, HNF4α and HNF6 were absent in hepatoblasts of the early embryonic liver. Hnf4α has been shown to be essential in hepatoblast differentiation and the establishment of normal hepatic parenchymal epithelium (Parviz et al., 2003). Conditional deletion of Hnf4α resulted in some livers that lost their cohesive structure, had large lesions, and were falling apart. Recently, HNF4α has been shown to regulate the expression of multiple proteins required in cell junction assembly and adhesion during liver development (Battle et al., 2006). In Hnf6-/- mutants, differentiation of hepatoblasts was abnormal with excessive formation of biliary epithelial cells and cysts (Clotman et al., 2002). The absence of HNF4α and HNF6 in the early liver of Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants most likely explains the severe defects in the hepatic epithelium seen later in development. These defects included a loss of cohesive structure in the ventral liver periphery, severe cystogenesis, and the presence of cystic epithelium with both biliary-like (CK-positive) and hepatocyte-like (HNF4α-positive) cells. Hnf4α and Hnf6 are components of a complex genetic network of liver-enriched transcription factors, and how Hhex fits into this network remains to be determined. We suggest that Hhex has an essential role in hepatoblast differentiation in the early embryonic liver through positive regulation of Hnf4α and Hnf6 expression. Why Hhex is absolutely essential for HNF4α and HNF6 expression only in the early hepatoblast is unknown, but other LETF’s, such as Foxa2 (HNF3β) and HNF4α, have also been shown to function differently in the fetal versus the adult liver (Sund et al., 2000; Hayhurst et al., 2001). Interestingly, HNF6 has been shown to regulate the expression of Hnf4α in the embryonic liver (Braincot et al., 2004). The regulation of Hnf4α expression is complex with two promoters, P1 and P2, and their respective transcripts Hnf4α1 and Hnf4α7 (Briancot et al., 2004; Odom et al., 2004). HNF6 activates the P2 promoter in the embryonic liver, and throughout development there is a switch to almost exclusively P1 promoter activity in mature hepatocytes (Briancot et al., 2004). We have identified two conserved Hhex consensus binding sites approximately 15kb upstream of the Hnf6 transcription start site (data not shown) suggesting that Hnf6 may be a direct target of Hhex.

Hhex is essential during late embryogenesis for proper development of intrahepatic bile ducts

Deletion of Hhex in the liver during late embryogenesis in Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants resulted in abnormal morphogenesis of IHBD. In the mutant livers, portal tracts were surrounded by biliary cysts and irregular duct-like structures. Further, many periportal cells lining the cysts lacked HNF1β expression. Hnf1β has been shown to be essential in normal differentiation and development of IHBD in mice (Coffinier et al., 2002). In mutants with a targeted deletion of Hnf1β in the embryonic liver, the ductal plate was very disorganized with irregular duct-like structures at E17.5. We believe the absence of HNF1β in some cystic epithelial cells most likely reflects abnormal periportal cell differentiation. In support of this, we have shown that some cystic biliary cells were positive for HNF4α. These abnormal hybrid cells expressed both hepatoblast/hepatocyte (HNF4α) and biliary (CK) cell markers, and have previously been described in the Hnf6-/- mutant (Clotman et al., 2005). HNF6 is a member of the Onecut family of transcription factors and was shown to be required for IHBD morphogenesis by regulation of hepatoblast differentiation (Clotman et al., 2002). The presence of hybrid cells in Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants suggests that Hhex is required for proper differentiation of hepatoblasts into hepatocytes and biliary cells. Perhaps in the absence of Hhex, some hepatoblasts arrest their differentiation or certain hepatoblasts/hepatocytes may abnormally activate biliary cell differentiation.

Additionally, we have detected biliary cysts that were present throughout the parenchymal tissue (i.e. in the absence of a branch of the portal vein), which implies the normal mechanism of biliary cell induction in hepatoblasts adjacent to the mesenchyme of the portal vein is not functioning in these mutants. Similar results were seen in the Hnf6-/-;Oc-2-/- double knockout mice and it was suggested that these Onecut transcription factors control cell lineage decision by regulating periportal TGFβ signaling (Clotman et al., 2005). We did not detect any obvious differences in Hnf6 expression during late embryogenesis between Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants and controls by immunohistochemistry (data not shown). Further studies are necessary to determine whether Hhex has a similar role in biliary cell differentiation as HNF6 by regulating the expression of components of the TGFβ pathway.

The liver phenotype in our Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mice resembles human polycystic liver disease. The most common forms of this disease involve a slow, progressive cystogenesis that can result in organ failure (reviewed in Tahvanainen et al., 2005). In most cases, the disease usually presents in the fourth or fifth decade of life, and liver function tests are often normal (Arnold and Harrison, 2005). Blood serum levels of total bilirubin, albumin, alanine transferase, and total protein from Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mice at 2 months of age were normal, but alkaline phosphatase was increased two-fold in severely affected mutants (data not shown). Polycystic liver disease is also associated with abnormal proliferation of the cystic epithelia (reviewed in Alvaro et al., 2006). In concurrence with this, Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants have cystic epithelia with greater than a four-fold increase in proliferation compared to control biliary cells. Another characteristic abnormality in all forms of polycystic disease of the liver is ductal plate malformation (DPM), which is defined as an arrest in embryonic morphogenesis of the ductal plate (reviewed by Desmet, 2004). Our findings of DPM in Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants indicate a failure in remodeling of the ductal plate and suggest Hhex may have a role in this process during embryogenesis.

The differences seen in the severity of the liver phenotypes between the Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants and the Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants can be explained by the difference in the timing of Hhex deletion (summarized in Figure 9). In Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants, deletion of Hhex appeared to be complete in the hepatobiliary primordia by E10.5, and this resulted in an absence of HNF4α and HNF6 expression in the liver at E13.5. Whereas in Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- mutants, deletion of Hhex was restricted to endodermal cells of the liver and did not appear to be complete in most mutants until late embryogenesis with no affect on HNF4α or HNF6 expression in the early liver. Our findings regarding the timing of deletion of a floxed allele using these Cre transgenics are similar to previous studies (Parviz et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2005a; Lee et al., 2005b). The difference between the Hhex-/- mutant and the Foxa3-Cre;Hhexd2,3/- conditional mutant is probably due to strain-specific differences between these mice and/or perdurance of Hhex protein in the conditional mutant in early hepatoblasts migrating from the hepatic diverticulum to form the liver bud.

It is interesting to note here that Hhex has been shown to play a crucial role in several cell-lineage differentiation pathways including hematopoiesis, lymphopoiesis, cardiogenesis, and vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation (Kubo et al., 2005; Bogue et al., 2003; Foley and Mercola, 2005; Oyama et al., 2004). Our results suggest that Hhex has a similar role in regulating hepatoblast differentiation into hepatocytes and biliary cells. In support of this hypothesis, liver regeneration studies in rat have shown that Hhex expression is upregulated after partial hepatectomy (Tanaka et al., 1999). We are currently searching for Hhex target genes involved in these cell fate decisions.

Conclusions

We have shown for the first time that Hhex has distinct functions during different stages of liver and biliary tract development. Our work has demonstrated essential roles for Hhex in hepatoblast differentiation and morphogenesis of the bile ducts. Future studies on the Hhex gene in hepatocyte and biliary cell differentiation should lead to novel insights into hepatobiliary disorders in humans.

Supplementary Material

(A) Schematic showing targeting vector with Hhex wild-type, neoflox, flox, and d2,3 alleles. The positions of relevant restriction sites, PCR primers, and southern probe are shown. A neomycin (neo) resistance cassette was inserted into the first intron of Hhex to allow for selection. The neo cassette was flanked by two FRT sites for FLP recombinase-mediated removal of neo from the Hhexneoflox allele to generate the Hhexflox allele. Two loxP sites were inserted into flanking positions around exons 2 and 3 of Hhex in the targeting vector. Exons 2 and 3, which encode the homeodomain of Hhex, could then be removed by Cre-mediated recombination to generate the conditional null allele (Hhexd2,3). A positive clone was chosen from approximately 300 screened, and verified by a combination of Southern hybridization, PCR, restriction digest, and sequencing (data not shown). (B) Southern and PCR genotyping of Hhexneoflox mice. Genomic DNA from Hhex+/+ (wild-type) and Hhexneoflox/+ mice was digested with EcoRV, or EcoRV and SpeI. Hhex+/+ DNA cut with EcoRV generates a single 12kb band, and cut with EcoRV and SpeI generates a 10.7kb band. Hhexneoflox/+ DNA cut with EcoRV generates the 12kb wild-type (wt) band plus an additional 9.1kb neoflox (nf) band (from the EcoRV site in neo), and cut with EcoRV and SpeI generates the 10.7kb wildtype band plus an 8.8kb neoflox band. Multiplex PCR using primers 1, 2, and 3 to distinguish the wildtype (678bp) and neoflox (561bp) alleles. (C) Southern and PCR genotyping of Hhexflox mice. Genomic DNA from Hhex+/+, Hhexflox/+, and Hhexflox/flox mice was digested with EcoRV, or EcoRV and SpeI. Hhexflox/+ DNA cut with EcoRV generates a 12.2kb flox (fl) band, and a 12kb wildtype band. When cut with EcoRV and SpeI, Hhexflox/+ DNA generates a 10.7kb wildtype band and an 8.8kb flox band. Hhexflox/flox DNA cut with EcoRV generates a single 12.2kb flox band, and with EcoRV and SpeI generates an 8.8kb flox band. Multiplex PCR reaction with primers 1, 2, and 3 to distinguish Hhex wildtype (678bp) and flox (810bp) alleles. Primer 3 was included to verify the absence of the neo cassette. (D) PCR detection and sequencing of Hhexd2,3 using primers 1, 2 and 4. Hhexflox/+ mice were bred with Alfp-Cre;Hhex+/- mice to generate Hhex conditional null mutants. Hhexd2,3 was detected in Hhex conditional null (Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/-) liver DNA, but not in control (Hhexflox/-) liver DNA as expected. The Hhexflox allele is detected in liver DNA from Hhex conditional null mice because Hhex is only deleted in endodermal-derived cells of the liver. Sequencing results of the Hhexd2,3 allele PCR product confirmed exons 2 and 3 of Hhex were deleted. Hhex intron 1 (blue) and intron 3 (red) have been recombined together separated by the FRT and loxP linker sequences. XhoI, SpeI, FRT, loxP, and SpeI sites are underlined (respectively from 5’-3’). Primer sequences are available by request. Southern hybridization was performed according to standard procedures.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tim Nottoli for help with generating the transgenic mice. We are grateful to Jim Boyer, Steve Somlo, Martina Brueckner, and George Porter for thoughtful comments on the experimental results. Thanks to Vicky Prince for comments on the manuscript. Clifford W. Bogue is a member of the Yale Liver Center. This work was funded by NIH grants #T32 HL07272 and #RO1-DK061146 (C.W.B.) and #P01-DK049210 (K.H.K.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alvaro D, Mancino MG, Onori P, Franchitto A, Alpini G, Francis H, Glaser S, Gaudio E. Estrogens and the pathophysiology of the biliary tree. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3537–45. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i22.3537. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold HL, Harrison SA. New advances in evaluation and management of patients with polycystic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2569–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00263.x. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle MA, Konopka G, Parviz F, Gaggl AL, Yang C, Sladek FM, Duncan SA. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha orchestrates expression of cell adhesion proteins during the epithelial transformation of the developing liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8419–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600246103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogue CW, Ganea GR, Sturm E, Ianucci R, Jacobs HC. Hex expression suggests a role in the development and function of organs derived from foregut endoderm. Dev Dyn. 2000;219:84–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1028>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogue CW, Zhang PX, McGrath J, Jacobs HC, Fuleihan RL. Impaired B cell development and function in mice with a targeted disruption of the homeobox gene Hex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:556–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0236979100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bort R, Signore M, Tremblay K, Barbera JP, Zaret KS. Hex homeobox gene controls the transition of the endoderm to a pseudostratified, cell emergent epithelium for liver bud development. Dev Biol. 2006;290:44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bort R, Martinez-Barbera JP, Beddington RS, Zaret KS. Hex homeobox gene-dependent tissue positioning is required for organogenesis of the ventral pancreas. Development. 2004;131:797–806. doi: 10.1242/dev.00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briancot N, Bailly A, Clotman F, Jacquemin P, Lemaigre FP, Weiss MC. Expression of the 7 Isoform of Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor (HNF) 4 Is Activated by HNF6/OC-2 and HNF1 and Repressed by HNF41 in the Liver. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33398–33408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405312200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffinier C, Gresh L, Fiette L, Tronche F, Schutz G, Babinet C, Pontoglio M, Yaniv M, Barra J. Bile system morphogenesis defects and liver dysfunction upon targeted deletion of HNF1beta. Development. 2002;129:1829–38. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clotman F, Jacquemin P, Plumb-Rudewiez N, Pierreux CE, Van der Smissen P, Dietz HC, Courtoy PJ, Rousseau GG, Lemaigre FP. Control of liver cell fate decision by a gradient of TGF beta signaling modulated by Onecut transcription factors. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1849–54. doi: 10.1101/gad.340305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clotman F, Lannoy VJ, Reber M, Cereghini S, Cassiman D, Jacquemin P, Roskams T, Rousseau GG, Lemaigre FP. The onecut transcription factor HNF6 is required for normal development of the biliary tract. Development. 2002;129:1819–28. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denson LA, Karpen SJ, Bogue CW, Jacobs HC. Divergent homeobox gene hex regulates promoter of the Na(+)-dependent bile acid cotransporter. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G347–55. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.2.G347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmet VJ. Pathogenesis of ductal plate malformation. J Gastro and Hepat. 2004;19:S356–S360. [Google Scholar]

- Drewes T, Senkel S, Holewa B, Ryffel GU. Human hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 isoforms are encoded by distinct and differentially expressed genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:925–31. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois AM. The embryonic liver. In: Rouiller C, editor. The Liver, Morphology, Biochemistry, Physiology. Academic Press; New York: 1963. pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fabris L, Strazzabosco M, Crosby HA, Ballardini G, Hubscher SG, Kelly DA, Neuberger JM, Strain AJ, Joplin R. Characterization and isolation of ductular cells coexpressing neural cell adhesion molecule and Bcl-2 from primary cholangiopathies and ductal plate malformations. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1599–612. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65032-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley AC, Mercola M. Heart induction by Wnt antagonists depends on the homeodomain transcription factor Hex. Genes Dev. 2005;19:387–96. doi: 10.1101/gad.1279405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda A, Kawaguchi Y, Furuyama K, Kodama S, Horiguchi M, Kuhara T, Koizumi M, Boyer DF, Fujimoto K, Doi R, Kageyama R, Wright CV, Chiba T. Ectopic pancreas formation in Hes1 -knockout mice reveals plasticity of endodermal progenitors of the gut, bile duct, and pancreas. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1484–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI27704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh B, Ganea GR, Denson LA, Iannucci R, Jacobs HC, Bogue CW. Immunocytochemical characterization of murine Hex, a homeobox-containing protein. Pediatr Res. 2000;48:634–8. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200011000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire JR, Torres VE, Holley KE, et al. Renal epithelial hyperplastic and neoplastic proliferation in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;9:27–38. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(87)80158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallaq H, Pinter E, Enciso J, McGrath J, Zeiss C, Brueckner M, Madri J, Jacobs HC, Wilson CM, Vasavada H, Jiang X, Bogue CW. A null mutation of Hhex results in abnormal cardiac development, defective vasculogenesis and elevated Vegfa levels. Development. 2004;131:5197–5209. doi: 10.1242/dev.01393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayhurst GP, Lee YH, Lambert G, Ward JM, Gonzalez FJ. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha (nuclear receptor 2A1) is essential for maintenance of hepatic gene expression and lipid homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1393–403. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1393-1403.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MH. The atlas of mouse development. Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Keng VW, Yagi H, Ikawa M, Nagano T, Myint Z, Yamada K, Tanaka T, Sato A, Muramatsu I, Okabe M, Sato M, Noguchi T. Homeobox gene Hex is essential for onset of mouse embryonic liver development and differentiation of the monocyte lineage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:1155–61. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keng VW, Fujimori KE, Myint Z, Tamamaki N, Nojyo Y, Noguchi T. Expression of Hex mRNA in early murine postimplantation embryo development. FEBS Lett. 1998;426:183–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupczak-Hollis K, Wang X, Kalinichenko VV, Gusarova GA, Wang IC, Dennewitz MB, Yoder HM, Kiyokawa H, Kaestner KH, Costa RH. The mouse Forkhead Box m1 transcription factor is essential for hepatoblast mitosis and development of intrahepatic bile ducts and vessels during liver morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2004;276:74–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo A, Chen V, Kennedy M, Zahradka E, Daley GQ, Keller G. The homeobox gene HEX regulates proliferation and differentiation of hemangioblasts and endothelial cells during ES cell differentiation. Blood. 2005;105:4590–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Sund NJ, Behr R, Herrera PL, Kaestner KH. Foxa2 is required for the differentiation of pancreatic alpha-cells. Dev Biol. 2005a;278:484–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Friedman JR, Fulmer JT, Kaestner KH. The initiation of liver development is dependent on Foxa transcription factors. Nature. 2005b;435:944–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaigre F, Zaret KS. Liver development update: new embryo models, cell lineage control, and morphogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:582–90. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.08.004. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Barbera JP, Clements M, Thomas P, Rodriguez T, Meloy D, Kioussis D, Beddington RS. The homeobox gene Hex is required in definitive endodermal tissues for normal forebrain, liver and thyroid formation. Development. 2000;127:2433–45. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy A, Gersenstein M, Vintersten K, Behringer R. Manipulating the mouse embryo: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Offield MF, Jetton TL, Labosky PA, Ray M, Stein RW, Magnuson MA, Hogan BL, Wright CV. PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development. 1996;122:983–95. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama Y, Kawai-Kowase K, Sekiguchi K, Sato M, Sato H, Yamazaki M, Ohyama Y, Aihara Y, Iso T, Okamaoto E, Nagai R, Kurabayashi M. Homeobox protein Hex facilitates serum responsive factor-mediated activation of the SM22alpha gene transcription in embryonic fibroblasts. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1602–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000138404.17519.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parviz F, Matullo C, Garrison WD, Savatski L, Adamson JW, Ning G, Kaestner KH, Rossi JM, Zaret KS, Duncan SA. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha controls the development of a hepatic epithelium and liver morphogenesis. Nat Genet. 2003;34:292–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierreux CE, Vanhorenbeeck V, Jacquemin P, Lemaigre FP, Rousseau GG. The transcription factor Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor-6/Onecut-1 controls the expression of its paralog Onecut-3 in developing mouse endoderm. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51298–304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CI, Buchholz F, Galloway J, Sequerra R, Kasper J, Ayala R, Stewart AF, Dymecki SM. High-efficiency deleter mice show that FLPe is an alternative to Cre-loxP. Nat Genet. 2000;25:139–40. doi: 10.1038/75973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiojiri N. Development and differentiation of bile ducts in the mammalian liver. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;39:328–35. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19971115)39:4<328::AID-JEMT3>3.0.CO;2-D. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiojiri N. The origin of intrahepatic bile duct cells in the mouse. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1984;79:25–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiojiri N. The differentiation of the hepatocytes and intra- and extrahepatic bile duct cells in mouse embryo. J Fac Sci Univ Tokyo IV. 1979;14:241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Sumazaki R, Shiojiri N, Isoyama S, Masu M, Keino-Masu K, Osawa M, Nakauchi H, Kageyama R, Matsui A. Conversion of biliary system to pancreatic tissue in Hes1-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 2004;36:83–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sund NJ, Ang SL, Sackett SD, Shen W, Daigle N, Magnuson MA, Kaestner KH. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 3beta (Foxa2) is dispensable for maintaining the differentiated state of the adult hepatocyte. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5175–83. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5175-5183.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Inazu T, Yamada K, Myint Z, Keng VW, Inoue Y, Taniguchi N, Noguchi T. cDNA cloning and expression of rat homeobox gene, Hex, and functional characterization of the protein. Biochem J. 1999;339(Pt 1):111–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahvanainen E, Tahvanainen P, Kaariainen H, Hockerstedt K. Polycystic liver and kidney diseases. Ann Med. 2005;37:546–55. doi: 10.1080/07853890500389181. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PQ, Brown A, Beddington RS. Hex: a homeobox gene revealing peri-implantation asymmetry in the mouse embryo and an early transient marker of endothelial cell precursors. Development. 1998;125:85–94. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace KN, Yusuff S, Sonntag JM, Chin AJ, Pack M. Zebrafish Hhex regulates liver development and digestive organ chirality. Genesis. 2001;30:141–3. doi: 10.1002/gene.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Rubins NE, Ahima RS, Greenbaum LE, Kaestner KH. Foxa2 integrates the transcriptional response of the hepatocyte to fasting. Cell Metab. 2005;2:141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Schematic showing targeting vector with Hhex wild-type, neoflox, flox, and d2,3 alleles. The positions of relevant restriction sites, PCR primers, and southern probe are shown. A neomycin (neo) resistance cassette was inserted into the first intron of Hhex to allow for selection. The neo cassette was flanked by two FRT sites for FLP recombinase-mediated removal of neo from the Hhexneoflox allele to generate the Hhexflox allele. Two loxP sites were inserted into flanking positions around exons 2 and 3 of Hhex in the targeting vector. Exons 2 and 3, which encode the homeodomain of Hhex, could then be removed by Cre-mediated recombination to generate the conditional null allele (Hhexd2,3). A positive clone was chosen from approximately 300 screened, and verified by a combination of Southern hybridization, PCR, restriction digest, and sequencing (data not shown). (B) Southern and PCR genotyping of Hhexneoflox mice. Genomic DNA from Hhex+/+ (wild-type) and Hhexneoflox/+ mice was digested with EcoRV, or EcoRV and SpeI. Hhex+/+ DNA cut with EcoRV generates a single 12kb band, and cut with EcoRV and SpeI generates a 10.7kb band. Hhexneoflox/+ DNA cut with EcoRV generates the 12kb wild-type (wt) band plus an additional 9.1kb neoflox (nf) band (from the EcoRV site in neo), and cut with EcoRV and SpeI generates the 10.7kb wildtype band plus an 8.8kb neoflox band. Multiplex PCR using primers 1, 2, and 3 to distinguish the wildtype (678bp) and neoflox (561bp) alleles. (C) Southern and PCR genotyping of Hhexflox mice. Genomic DNA from Hhex+/+, Hhexflox/+, and Hhexflox/flox mice was digested with EcoRV, or EcoRV and SpeI. Hhexflox/+ DNA cut with EcoRV generates a 12.2kb flox (fl) band, and a 12kb wildtype band. When cut with EcoRV and SpeI, Hhexflox/+ DNA generates a 10.7kb wildtype band and an 8.8kb flox band. Hhexflox/flox DNA cut with EcoRV generates a single 12.2kb flox band, and with EcoRV and SpeI generates an 8.8kb flox band. Multiplex PCR reaction with primers 1, 2, and 3 to distinguish Hhex wildtype (678bp) and flox (810bp) alleles. Primer 3 was included to verify the absence of the neo cassette. (D) PCR detection and sequencing of Hhexd2,3 using primers 1, 2 and 4. Hhexflox/+ mice were bred with Alfp-Cre;Hhex+/- mice to generate Hhex conditional null mutants. Hhexd2,3 was detected in Hhex conditional null (Alfp-Cre;Hhexd2,3/-) liver DNA, but not in control (Hhexflox/-) liver DNA as expected. The Hhexflox allele is detected in liver DNA from Hhex conditional null mice because Hhex is only deleted in endodermal-derived cells of the liver. Sequencing results of the Hhexd2,3 allele PCR product confirmed exons 2 and 3 of Hhex were deleted. Hhex intron 1 (blue) and intron 3 (red) have been recombined together separated by the FRT and loxP linker sequences. XhoI, SpeI, FRT, loxP, and SpeI sites are underlined (respectively from 5’-3’). Primer sequences are available by request. Southern hybridization was performed according to standard procedures.