Abstract

Although cellular uptake of vitamin E was initially described as a passive process, recent studies in the liver and brain have shown that SR-BI is involved in this phenomenon. As SR-BI is expressed at high levels in the intestine, the present study addressed the involvement of SR-BI in vitamin E trafficking across enterocytes. Apical uptake and efflux of the main dietary forms of vitamin E was examined using Caco-2 TC-7 cell monolayers as a model of human intestinal epithelium. RRR-γ-tocopherol bioavailability was compared between wild-type mice and mice overexpressing SR-BI in the intestine. The effect of vitamin E on enterocyte SR-BI mRNA levels was measured by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Concentration-dependent curves for vitamin E uptake were similar for RRR-α-, RRR-γ- and DL-α-tocopherol. RRR-α-tocopherol transport was dependent on incubation temperature, with a 60% reduction in absorption at 4°C compared to 37°C (p<0.05). Vitamin E flux in enterocytes was directed from the apical to the basal side, with a relative 10-fold reduction in the transfer process when measured in the opposite direction (p<0.05). Co-incubation with cholesterol, γ-tocopherol or lutein significantly impaired α-tocopherol absorption. Anti-human SR-BI antibodies and BLT1 (a chemical inhibitor of lipid transport via SR-BI) blocked up to 80% of vitamin E uptake and up to 30 % of apical vitamin E efflux (p<0.05), and similar results were obtained for RRR-γ-tocopherol. SR-BI mRNA levels were not significantly modified after a 24-hour incubation of Caco-2 cells with vitamin E. Finally, RRR-γ-tocopherol bioavailability was 2.7-fold higher in mice overexpressing SR-BI than in wild-type mice (p<0.05). The present data show for the first time that vitamin E intestinal absorption is, at least partly, mediated by SR-BI.

Keywords: Absorption; Animals; Antigens, CD36; metabolism; physiology; Binding, Competitive; Biological Transport; Caco-2 Cells; Cell Differentiation; Cholesterol; metabolism; Dose-Response Relationship, Drug; Enterocytes; metabolism; Epithelial Cells; metabolism; Humans; Intestines; metabolism; Lipids; chemistry; Mice; Mice, Transgenic; Micelles; RNA, Messenger; metabolism; Temperature; Time Factors; Tocopherols; metabolism; Vitamin E; metabolism; alpha-Tocopherol; metabolism; gamma-Tocopherol; metabolism

Vitamin E is a fat-soluble micronutrient which occurs in nature in eight different forms: RRR-α-, β-, γ-, and δ-tocopherol and RRR-α-, β-, γ-, and δ-tocotrienol. The human diet mainly provides RRR-α-tocopherol (RRR-α-T) and RRR-γ-tocopherol (RRR-γ-T), while supplements generally supply vitamin E as DL-α-tocopherol (DL-α-T) or DL-α-tocopherol acetate. Although a recent study has described the fate of vitamin E in the human digestive tract (1), the major steps from micellar uptake to enterocyte trafficking and incorporation into chylomicrons are largely unknown (2). It has long been assumed that vitamin E, like other fat-soluble (micro)nutrients, is absorbed by a passive process. However, recent data suggest that the absorption of fat-soluble (micro)nutrients is more complex than previously thought. More precisely, several transporters, i.e. ABC transporters (3), Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 (NPC1L1) (4), cluster determinant 13 (CD13) (5) and Scavenger Receptor class B type 1 (SR-BI) (6), have been implicated in cholesterol trafficking in the enterocyte, and it has recently been shown that the absorption of the two carotenoids lutein and β-carotene is at least partly mediated by SR-BI (7,8). Interestingly, recent data add support to the hypothesis of involvement of SR-BI in vitamin E transport in the enterocyte. Firstly, SR-BI is expressed at substantial levels in the intestine (9). Second, SR-BI significantly contributes to the selective uptake of HDL-associated vitamin E in both porcine brain (10) and rat pneumocytes (11). Third, an SR-BI analog was reported to mediate cellular uptake of α-tocopherol in Drosophila (12). Fourth, vitamin E metabolism is abnormal in SR-BI-deficient mice (13). The objectives of this study were to assess whether intestinal absorption of vitamin E is protein-mediated, and to determine whether SR-BI is involved in this phenomenon.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

RRR-α-T (≥ 99% pure), DL-α-T (≥ 98% pure) and RRR-γ-T (≥ 97% pure) were purchased from Flucka (Vaulx-en-Velin, France). Carotenoids (β-carotene, lycopene and lutein) were generously provided by DSM LTD (the successor of F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Tocol, used as internal standard for HPLC analysis, was purchased from Lara Spiral (Couternon, France). 2-oleoyl-1-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (phosphatidylcholine), 1-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (lysophosphatidylcholine), monoolein, free cholesterol, oleic acid, sodium taurocholate and pyrogallol were purchased from Sigma-Aldricht (Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France). Sulfo-NHS-LC Biotin was purchased from Uptima-Interchim (Montluçon, France). Streptavidine agarose solution (manufactured by Oncogene Research Products), n-octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (manufactured by Calbiochem) was purchased from VWR international SAS (Strasbourg, France). Mouse monoclonal IgG raised against the external domain (amino acids 104 – 294) of human SR-BI, also known as CLA-1, was purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY, U.S.A.). BLT1 (blocks lipid transport 1, a chemical inhibitor of lipid transport mediated by SR-BI) was purchased from Chembridge (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 4.5 g/L glucose and trypsin-EDTA (500 mg/L and 200 mg/L, respectively) was purchased from BioWhittaker (Fontenay-sous-Bois, France), fetal bovine serum (FBS) came from Biomedia (Issy-les-Moulineaux, France), and non-essential amino acids, penicillin/streptomycin and PBS containing 0.1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 (PBS-CM) were purchased from Gibco BRL (Cergy-Pontoise, France). The protease inhibitor cocktail was a gift from F. Tosini (Avantage Nutrition, Marseille, France).

Preparation of tocopherol-rich micelles

For delivery of tocopherol to cells, mixed micelles, which had similar lipid composition than those found in vivo (14), were prepared as previously described (7) to obtain the following final concentrations: 0.04 mM phosphatidylcholine, 0.16 mM lysophosphatidylcholine, 0.3 mM monoolein, 0.1 mM free cholesterol, 0.5 mM oleic acid, 5 to 90 μM tocopherol (1) and 5 mM taurocholate. Concentration of tocopherol in the micellar solutions was checked before each experiment.

Preparation of tocopherol-rich emulsions

For delivery of tocopherol to mice, emulsions were prepared as follows. An appropriate volume of tocopherol stock solution was transferred to eppendorfs to obtain a final amount of 5 mg in each tube. Stock solution solvent was carefully evaporated under nitrogen. Dried residue was solubilized in 100 μL of Isio 4 vegetable oil (Lesieur, Asnières-sur-Seine, France), and 200 μL of physiological serum were added. The mixture was vigorously mixed in ice-cold water in a sonication bath (Branson 3510, Branson) for 15 min and used for force-feeding within 10 min.

Cell culture

Caco-2 clone TC-7 cells (15,16) were a gift from Dr. M. Rousset (U178 INSERM, Villejuif, France). Cells were cultured in the presence of DMEM supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated FBS, 1% non-essential amino acid, and 1% antibiotics (complete medium), as previously described (7).

For each experiment, cells were seeded and grown on transwells as previously described (7) to obtain confluent differentiated cell monolayers. Twelve hours prior to each experiment, the medium used in apical and basolateral chambers was a serum-free complete medium.

During preliminary tests, the integrity of the cell monolayers was checked by measuring trans-epithelial electrical resistance before and after the experiment using a voltohmmeter fitted with a chopstick electrode (Millicell ERS; Millipore, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France).

Identification of transport characteristics: uptake and efflux measurement

At the beginning of each experiment, cell monolayers were washed twice with 0.5 mL PBS. For uptake experiments, the apical or basolateral side of the cell monolayers received the tocopherol-rich micelles, whereas the other side received the serum-free complete medium. Cells were incubated for 15 min at either 37°C or 4°C, depending on the experiment. Incubation time was chosen after a preliminary experiment measuring maximal absorption rate, in order to obtain sufficient amounts of absorbed tocopherol for accurate measurements. At the end of each experiment, media from each side of the cell monolayer were harvested. Cells were washed twice in 0.5 mL ice-cold PBS containing 10 mM taurocholate to eliminate adsorbed tocopherol, then scraped and collected in 2 mL PBS. Absorbed tocopherol was estimated as tocopherol found in scraped cells plus tocopherol found on the opposite side of the cell monolayer (basolateral side when micellar tocopherol was added to the apical side, and vice versa).

For apical efflux experiments, the cells first received the tocopherol-rich micelles at the apical side for 60 minutes. They were then washed 3 times with PBS and received apical medium containing vitamin E acceptors, i.e. vitamin-E-free mixed micelles. Aliquots of apical and/or basolateral medium were taken at different times, and replaced by the same volume of new medium.

All the samples were stored at −80°C under nitrogen with 0.5% pyrogallol as a preservative before tocopherol extraction and HPLC analysis. Aliquots of cell samples without pyrogallol were used to assess protein concentrations using a bicinchoninic acid kit (Pierce, Montluçon, France).

Competition studies

With cholesterol

RRR-α- and RRR-γ-T uptake was measured after incubation of vitamin-E-rich mixed-micelles (70.4 μM) containing either no cholesterol, 0.1 mM cholesterol (control) or 0.2 mM cholesterol.

With other microconstituents

RRR-α- and RRR-γ-T uptake was measured after incubation of vitamin-E-rich mixed-micelles (final concentration: 40 μM) containing either no other microconstituent, RRR-γ-T (final concentration of 40 μM when RRR-α-T uptake was measured), RRR-α-T (final concentration of 40 μM when RRR-γ-T uptake was measured), or carotenoids (final concentration: 6.0 μM lutein, 2.8 μM β-carotene or 0.4 μM lycopene).

Involvement of proteins in tocopherol transport

Test for the localization of SR-BI in apical or basolateral membranes of Caco-2 TC-7 cells

Biotinylation of cell monolayers and dot blotting were performed as previously described (7). Blots were then incubated with the mouse anti-human SR-BI IgG at 1/1000 dilution. Anti-mouse IgG were used as secondary antibodies at 1/5000 dilution for visualization.

Tocopherol apical transport inhibition by anti-human SR-BI antibody

For uptake experiments, cell monolayers were incubated for 2 min with 3.75 μg/mL of anti-human SR-BI monoclonal antibody raised against the external domain before tocopherol-rich micelles were added. Previous experiments have shown that this antibody concentration allowed a maximal inhibition of absorption (7). Anti-human SR-BI antibody raised against the C-terminal domain, which is located at the internal side of the apical membrane, was used as a control at 3.75 μg/mL (17).

For efflux experiments, tocopherol-enriched cells (see previous section on uptake and efflux measurements) received apical medium containing 3.75 μg/mL of anti-human SR-BI antibody and vitamin-E-free mixed micelles (as acceptors) for up to 24 h.

Tocopherol apical transport inhibition by BLT1

BLT1 cytotoxicity had been controlled previously using a CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution assay (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.) (7). These control experiments showed that BLT1 was not toxic up to 10 μM. The effect of BLT1 on tocopherol uptake was assessed as follows: cell monolayers were pretreated with either DMSO (control) or BLT1 at 10 μM for 1 h. The cells then received tocopherol-rich mixed micelles with 10 μM of BLT1, and uptake was measured as described above.

For efflux experiments, tocopherol-enriched cells received apical medium supplemented with either DMSO or BLT1 at 10 μM and vitamin-E-free mixed micelles (as acceptors) for up to 6 h. Efflux was measured as described above.

Tocopherol bioavailability in mice overexpressing SR-BI in the intestine

Transgenic mice were created as follows: the SR-BI cDNA was obtained by digestion of pRC/CMV vector by restriction enzyme Hind III and Xba I. The apolipoprotein C III enhancer (−500/−890 pb)-apolipoprotein A IV promoter (−700 pb) was excised from pUCSH-CAT plasmids using restriction enzymes Xba I and Hind III. The construct containing the apolipoprotein C III enhancer-apolipoprotein A IV promoter to the intestinal specificity and the 1.8 kilobase cDNA fragment of murine SR-BI was cloned into the XbaI site of the pc DNA 1.1 vector. A linearized fragment of the construct was obtained by digestion of the vector by restriction enzymes Sal I and Avr II, and used to generate transgenic mice by standard procedures on a B6D2 background.

Detailed informations on the characteristics of SR-BI Tg mice are provided in the Bietrix et al’s paper (18). RNA analysis showed that SR-BI Tg mice had a 25 fold increase of SR-BI in the intestine as compared to wild type mice. Immunocytochemistry confirmed the intestinal overexpression of SR-BI in Tg mice and showed that the protein was located at the same sites than in wild type mice.

The mice were housed in a temperature-, humidity- and light-controlled room. They were given a standard chow diet and water ad libitum. They were fasted overnight before each experiment. On the day of the experiment, a first blood sample was obtained at fasting (zero baseline sample) by cutting the extremity of the tails. The mice were then force-fed with a RRR-γ-tocopherol-enriched emulsion. Additional blood samples were taken at 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 10 and 24 h after force-feeding. Plasma samples were stored at –80 °C until vitamin E analysis by HPLC.

Tocopherol extraction

Tocopherol was extracted from 500 μL aqueous samples using the following method. Distillated water was added to sample volumes below 500 μL to reach a final volume of 500μL. Tocol, which was used as internal standard, was added to the samples in 500 μL ethanol. The mixture was extracted once with one volume of hexane. The hexane phase obtained after centrifugation (500 g, 10 min, 4°C) was evaporated to dryness under nitrogen, and the dried extract was dissolved in 100 μL methanol. A volume of 5–20 μL was used for HPLC analysis.

Tocopherol analysis

RRR-α-, RRR-γ-, DL-α-, T and tocol were separated using a 250 × 4.6 nm RP C18, 5 μm Zorbax column (Interchim, Montluçon, France) and a guard column. The mobile phase was 100% methanol. Flow rate was 1.5 mL/min, and the column was kept at a constant temperature (30°C). The HPLC system comprised a Dionex separation module (P680 HPLC Pump and ASI-100 Automated Sample Injector, Dionex, Aix-en-Provence, France) and a Jasco fluorimetric detector (Jasco, Nantes, France). Tocopherols were detected at 325 nm after light emission at 292 nm, and identified by retention time compared with pure (>95%) standards. Quantification was performed using Chromeleon software (version 6.50 SP4 Build 1000) comparing peak area with standard reference curves. All solvents used were HPLC grade from SDS (Peypin, France).

Effect of vitamin E on SR-BI mRNA levels

Differentiated cell monolayers cultivated on filters were incubated with either 80 μM RRR-αT-rich micelles, 80 μM RRR-γ-T-rich micelles or tocopherol-free micelles (controls) for 24 h. Total RNA was isolated from the cells using RNA II nucleospin™ kits (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). The cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription of 1 μg total RNA using random hexamers as primers. An equivalent volume of 5 μl of cDNA solution was used for quantification of specific cDNA by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. The sequences of the primers for 18S RNA, used as an internal standard for sample normalization, have been published previously (19). The sequences of the forward and reverse human SR-BI primers were 5′-CGGCTCGGAGAGCGACTAC-3′ and 5′-ATAATCCCCTGAACCCAAGGA-3′, respectively.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR reactions were performed in duplicate on an ABI PRISM™ 7700 Sequence Detection System (PE Applied Biosystems) using SYBR green kits (Eurogentec, Angers, France), in line with the manufacturer’s instructions. A melt curve peak analysis was performed at the end of all real-time PCR runs to ensure that only the correct product was amplified. The relative levels of SR-BI mRNA were calculated as recommended by the manufacturer using the comparative ΔΔCt method (User Bulletin #2, ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System, PE Applied Biosystems), and then analyzed as described by Livak and Schmittgen (20).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SD. Differences between two groups of unpaired data were tested using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Values of p<0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Statview software, version 5.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, U.S.A.). Relationships between two variables were examined by regression analysis on KaleidaGraph version 3.6 software (Synergy software, Reading, PA, U.S.A.).

Results

Incorporation of tocopherol in mixed micelles

Increasing amounts of RRR-α-T, RRR-γ-T or DL-α-T, corresponding to theoretical final concentrations ranging from 2.5–90 μM, were added to the lipid mixture during micelle preparation, and the concentrations of tocopherol recovered in the mixed micelles was measured. The incorporation of all three tocopherols increased linearly (data not shown).

Effect of incubation time on tocopherol uptake

RRR-α-T and RRR-γ-T absorbed by the differentiated monolayers increased curvilinearly for up to 60 min of incubation for both a high (40 μM) and a low (2.5 μM) concentration (data not shown). At incubation time shorter than 15 min and at the low concentration, the amounts of tocopherol were absorbed were insufficient for accurate measurement. Thus, in order to remain as close as possible to the initial absorption rate and to obtain adequate tocopherol absorption, we decided to work at 15 min incubation. Competition studies were performed at 30 min, which approximately represents the time during which the bowel content remains in contact with duodenal cells during digestion (21). Finally, some absorption experiments were carried out at 60 min to increase differences between groups.

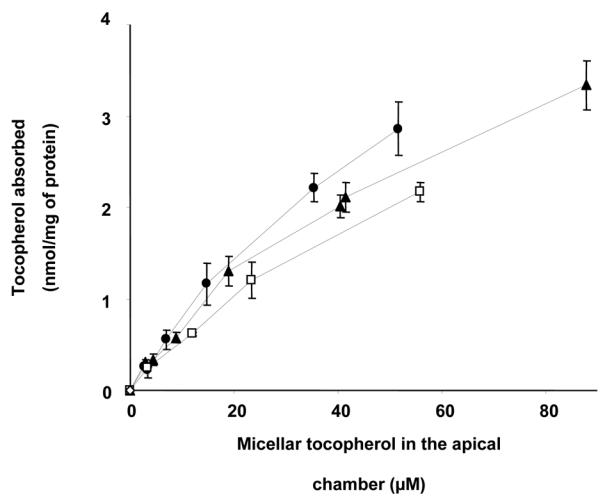

Effect of micellar tocopherol concentration on tocopherol absorption

Absorption of RRR-α-T, RRR-γ-T and DL-α-T was not linear (Fig. 1). The best fits were hyperbolic curves y = ax/(x + b), R² > 0.99. Apparent Qmax and K values were calculated (Table 1). Qmax represents maximal amount of tocopherol absorbed, and K represents the concentration of micellar tocopherol required to reach Qmax/2. Note that these values likely depend on micelle composition. There was no significant difference between vitamin E species in terms of affinity for a potential transporter (K values).

Fig. 1. Effect of micellar tocopherol concentration on tocopherol absorption by differentiated Caco-2 TC-7 cell monolayers at 37°C.

The apical side received FBS-free medium containing either RRR-α-T (●), RRR-γ-T (▲) or DL-α-T (□) -rich mixed micelles, and the basolateral side received FBS-free medium. Incubation time was 15 min. Data are means ± SD of 3 assays. Tocopherol absorbed = tocopherol recovered in the scraped cells + tocopherol recovered in the basolateral medium.

Table 1.

Parameters of tocopherol absorption as a function of micellar tocopherol concentrations in differentiated Caco-2 TC-7 cell monolayers.

| Vitamin E species | Apparent Qmax (nmole tocopherol absorbed/mg of protein) | Apparent K (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| RRR-α-T | 7.5 ± 0.6 | 84.3 ± 9.9 |

| RRR-γ-T | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 83.9 ± 11.5 |

| DL-α-T | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 88.3 ± 15.2 |

Tocopherol uptake was measured at 37°C after apical micellar tocopherol delivery in increasing concentrations. Incubation time was 15 min. Best fitting curves were hyperbolic curves y = ax/(b+x). Qmax represents the maximal amount of tocopherol absorbed, and K represents the concentration of micellar tocopherol required to reach Qmax/2. Data are means ± SD of 3 assays.

Effect of temperature and transport direction

Table 2 shows that there was (i) a significant decrease in RRR-α-T and RRR-γ-T absorption at 4°C compared to 37°C, and (ii) a drastic fall (up to 93.7%) in RRR-α-T and RRR-γ-T absorption when vitamin-E-rich micelles were supplied at the basolateral side compared with the apical side.

Table 2.

Effect of temperature and transport direction on RRR-α-tocopherol and RRR-γtocopherol absorption by differentiated Caco-2 TC-7 cell monolayers.

| RRR-α-tocopherol absorption (% of control) | RRR-γ-tocopherol absorption(% of control) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR-α-T micellar concentration | 4°C | Basolateral to apical | RRR-γ-T micellar concentration | 4°C | Basolateral to apical |

| 15 μM | 29.5 ± 6.9 * | 6.3 ± 0.0 * | 19 μM | 48.6 ± 5.7 * | 9.3 ± 0.5 * |

| 31 μM | 46.4 ± 9.6 * | 6.6 ± 2.5 * | 41 μM | 46.5 ± 4.9 * | 6.6 ± 1.6 * |

| 52 μM | 42.0 ± 8.0 * | 6.5 ± 0.9 * | 88 μM | 50.0 ± 18.2 * | 8.7 ± 0.1 * |

Tocopherol absorption (pmol/mg of protein) was measured at 37°C after apical micellar tocopherol delivery (control = 100%). Tocopherol uptake at 4 °C and tocopherol uptake following addition of micellar tocopherol in the basolateral chamber were compared to absorptions measured with vitamin E-rich micelles at the same micellar concentration at 37°C and in the apical to basolateral direction. Incubation time was 15 min. Data are means ± SD of 3 assays. An asterisk indicates that the value was significantly different to the control.

Effect of the amount of cholesterol incorporated in micelles with vitamin E on vitamin E absorption

Cholesterol is naturally present in micelles during digestion, but in concentrations that increase or decrease depending on diet and biliary secretion. RRR-α-T was significantly affected by micellar cholesterol concentration. More precisely, absorption decreased when micellar cholesterol concentration increased (Table 3). Similar results were obtained for RRR-γ-T (data not shown).

Table 3.

Effect of micellar cholesterol concentration on micellar RRR-α-tocopherol absorption by differentiated Caco-2 TC-7 cell monolayers.

| Micellar cholesterol concentration | RRR-α-T absorption (% of control) |

|---|---|

| 0.0 mM | 140.3 ± 13.1 * |

| 0.1 mM | 100.0 ± 12.6 |

| 0.2 mM | 93.3 ± 10.7 |

The apical side received FBS-free medium containing vitamin-E-rich mixed micelles (70.4 μM) with either no cholesterol, 0.1 mM cholesterol (control) or 0.2 mM cholesterol. The basolateral side received FBS-free medium. Incubation time was 30 min. Data are means ± SD of 3 assays. An asterisk indicates a significant difference with the control.

Effect of co-incubation with other fat-soluble microconstituents on vitamin E absorption

As shown in Table 4, co-incubation of micellar RRR-α-T with micellar RRR-γ-T significantly decreased the absorption of micellar RRR-α-T. Co-incubation with lutein also significantly decreased RRR-α-T absorption. Conversely there was no significant effect of β-carotene and lycopene on RRR-α-T absorption, but it should be noted that the micellar concentrations of these carotenoids were necessarily lower than for lutein due to their naturally lower solubility in micelles. Similar results were obtained with RRR-γ-T (data not shown).

Table 4.

Effect of RRR-γ-tocopherol and carotenoids on RRR-α-tocopherol absorption by differentiated Caco-2 TC-7 cell monolayers.

| Experimental conditions | RRR-α-T absorption (% of control) |

|---|---|

| 40 μM RRR-α-T + 40 μM RRR-γ-T | 59.5 ± 11.9* |

| 40 μM RRR-α-T + 6.0 μM lutein | 78.9 ± 6.7* |

| 40 μM RRR-α-T + 2.8 μM β-carotene | 80.6 ± 10.1 |

| 40 μM RRR-α-T + 0.4 μM lycopene | 97.0 ± 0.7 |

The apical side received FBS-free medium containing RRR-α-T-rich mixed micelles (40 μM) plus mixed micelles containing either no other microconstituent, RRR-γ-T, or carotenoids. The basolateral side received FBS-free medium. Incubation time was 30 min. Data are means ± SD of 3 assays. An asterisk indicates a significant difference with the control (RRR-α-T-rich micelles plus microconstituent-free mixed micelles).

Involvement of SR-BI in vitamin E transport across the apical membrane of the enterocyte

The biotinylation experiment we performed demonstrated that SR-BI is mainly located at the apical membrane of Caco-2 TC7 cells, according to our previous work (7).

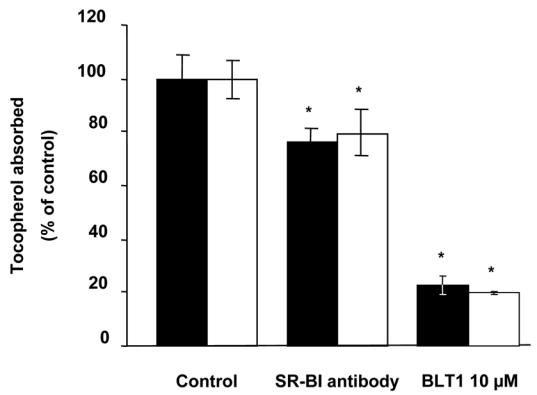

Uptake experiment

Figure 2 shows that addition of anti-human SR-BI antibody raised against the external domain significantly decreased RRR-α-T and RRR-γ-T apical absorption (by about 20%). Conversely, and as expected, the control antibody, i.e. the anti-human SR-BI antibody raised against an internal domain, did not impair vitamin E absorption (data not shown). The specific chemical inhibitor of SR-BI (BLT1) also significantly decreased RRR-α-T and RRR-γ-T absorption (by up to 80%).

Fig. 2. Effect of anti-human SR-BI antibody and BLT1 on RRR-α-T and RRR-γ-T absorption by differentiated Caco-2 TC-7 monolayers.

The apical sides of the cell monolayers were preincubated for 60 min with either the anti-human SR-BI antibody raised against the external domain at 3.75 μg/mL or BLT1 at 10 μM, and they then received FBS-free medium containing either RRR-α-T (■) or RRR-γ-T (□) -enriched mixed micelles at 40 μM. The basolateral sides received FBS-free medium. Incubation time was 60 min. Data are means ± SD of 3 assays. An asterisk indicates a significant difference with the control (assay performed with control antibody and without BLT1).

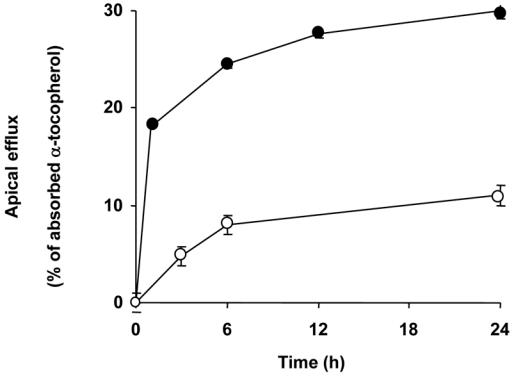

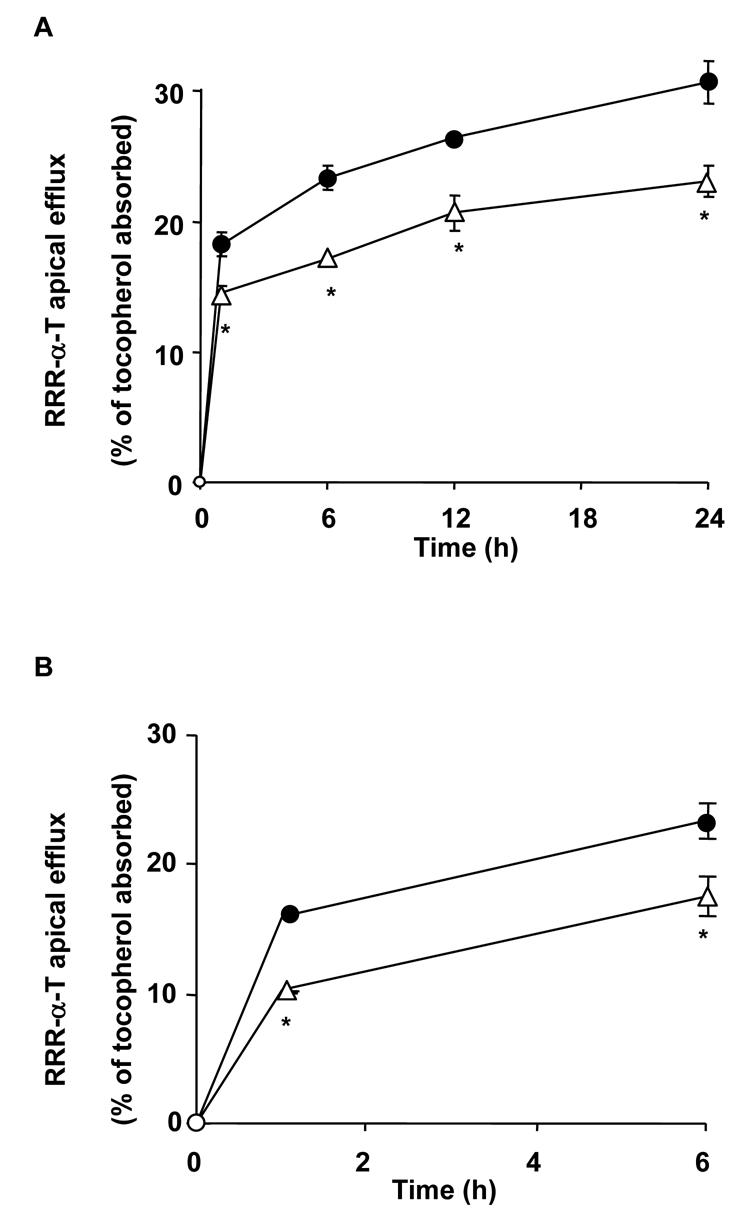

Apical efflux experiment

The apical effluxes of both RRR-α-T and RRR-γ-T (data not shown) increased dramatically (approx. 300% after 24 h) when a putative physiological acceptor of vitamin E, in this case vitamin-E-free mixed micelles, was added to the apical medium (Fig. 3). Adding either anti-human SR-BI antibody raised against the external domain or BLT1 at the apical side of the cells in the presence of vitamin-E-free mixed micelles significantly reduced the apical efflux of RRR-αT (Figs 4 A and B) and RRR-γ-T (data not shown, but similar for this vitamin).

Fig. 3. Effect of a physiological acceptor of vitamin E on RRR-α-T apical efflux by differentiated Caco-2 TC-7 cell monolayers.

Cells were enriched with RRR-α-T (see experimental procedures), and the apical side then received either FBS-free medium (○) or FBS-free medium containing tocopherol-free mixed micelles as physiologiocal acceptor (●). The basolateral side received FBS-free medium. Data are means ± SD of 3 assays.

Fig. 4. Effect of anti-human SR-BI antibody and BLT1 on RRR-α-T apical efflux by differentiated Caco-2 TC-7 cell monolayers.

Cells were enriched in RRR-α-T, and the apical side then received either FBS-free medium containing tocopherol-free-mixed micelles (●) or the same mixture plus anti-human SR-BI antibody (△, A) or plus BLT1 (△, B). The basolateral side received FBS-free medium. Aliquots of apical medium were taken at different times and replaced by the same volume of new medium. Data are means ± SD of 3 assays. An asterisk indicates a significant difference with the control (assay performed without antibody or inhibitor (●).

Regulation of enterocyte SR-BI mRNA levels by vitamin E

SR-BI mRNA levels were not significantly affected by incubation of differentiated cell monolayers with either RRR-α-T or RRR-γ-T (data not shown).

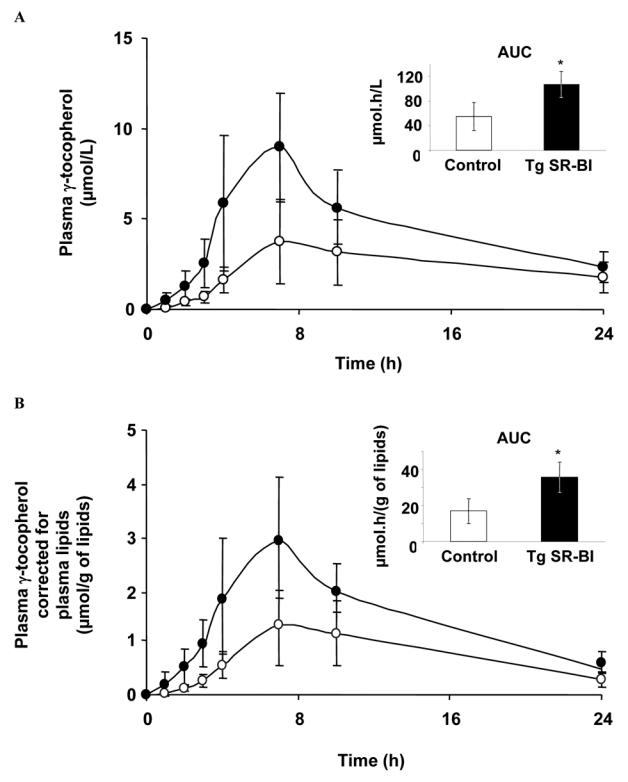

RRR-γ-T bioavailability in mice overexpressing SR-BI in the intestine

Plasma RRR-γ-T response (expressed as area under the postprandial 0–24 h curves) after force-feeding with RRR-γ-T-enriched emulsion was significantly higher in SR-BI Tg mice than in control mice: 106.9 ± 21.0 μmol.h/L vs. 54.9 ± 22.5 μmol.h/L (P = 0.0062; Fig. 5A). Plasma RRR-γ-T response remained significantly higher in SR-BI Tg mice than in wild-type mice after lipid adjustment of vitamin E response (35.7 ± 8.4 μmol.h/g of lipid vs. 17.0 ± 6.9 μmol.h/g of lipid, P = 0.0062, Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. Plasma γ-tocopherol response in wild-type mice and in mice overexpressing SR-BI in the intestine.

Mice were force-fed with an RRR-γ-T enriched emulsion. Data are means ± SD, n = 6 for control mice (○) and 5 for transgenic mice (●, SR-BI Tg).

A: Plasma RRR-γ-T. B: Plasma RRR-γ-T corrected for plasma lipids (cholesterol plus phospholipids plus triglycerides).

Discussion

To study in detail the mechanisms involved in vitamin E transport across the enterocyte, we used the frequently employed Caco-2 TC-7 cell model, which gives reproducible figures that correlate closely with human in vivo data (22). Our first result confirms that RRR-α-T, RRR-γ-T and DL-α-T show similar absorption patterns. This is in full agreement with previous studies in which there was no intestinal discrimination between α-tocopherol stereoisomers (23) nor between α- and γ-T forms (24). Taken together, the saturable uptake of vitamin E, the temperature dependency and the direction dependency strongly argue in favor of a protein-mediated uptake (25). Although it cannot be excluded that a fraction of vitamin E was absorbed by passive diffusion because of the 30–50% absorption observed at 4°C. After having demonstrated that a least a fraction of vitamin E was absorbed through a receptor mediated process the question that arises is “what transporter(s) is(are) involved?”. The best candidate is SR-BI, as its involvement in vitamin E trafficking has been demonstrated in several tissues (10,12,13,26). The finding that RRR-α-T and RRR-γ-T uptake in Caco-2 cells was inhibited by both anti-human SR-BI antibody and BLT1, which is a specific chemical inhibitor of SR-BI (27,28), is taken as initial evidence that SR-BI is involved in tocopherol uptake. The difference in inhibition efficiency between the antibody and the chemical inhibitor can be explained by the fact that the antibody was monoclonal, and consequently its high site specificity may lead to only a partial inhibition of SR-BI. The fact that we did not manage to fully inhibit tocopherol absorption suggests that other means of transport (passive diffusion or other transporters) are involved. In order to further examine the involvement of SR-BI in tocopherol absorption, we compared tocopherol bioavailability between wild-type mice and mice overexpressing SR-BI in the intestine. To do this, we used RRR-γ-T instead of RRR-α-T, for three reasons. First, as shown in this study in Caco-2 cells and as previously reported in the clinical study by Traber et al. (29), there is no intestinal discrimination between RRR-γ-T and RRR-α-T making it possible to choose between either of these isomers. Second, mice bred in-house had RRR-γ-T plasma concentrations close to zero, making RRR-γ-T equivalent to a tracer to measure newly absorbed tocopherol. Finally, since hepatic α-TTP discriminates between tocopherol isomers and resecretes more α-T than γ-T in VLDL, using γ-tocopherol generates less contamination of plasma tocopherol by tocopherol from hepatic origin, and thus provides a better evaluation of tocopherol secreted by the intestine, i.e. newly-absorbed. The results obtained in mice provide further evidence that SR-BI is involved in tocopherol absorption. Having obtained evidence that SR-B1 is involved in the apical uptake of tocopherols, and given that this transporter is involved in both lipid uptake and efflux (30), the obvious question was “is this transporter involved in the apical efflux of tocopherol as well?”. The fact that both anti-human SR-BI antibody and BLT1 inhibited tocopherol efflux from enterocytes to the apical side suggests that SR-BI also plays a role in intestinal tocopherol reverse transport.

Given that the main dietary sources of vitamin E are RRR-α and RRR-γ tocopherol, and that both vitamers are transported through the SR-BI, we raised the question of whether there was competition between these two forms of vitamin E. This is an important issue as γ-tocopherol has different biological properties to α-tocopherol, and it has been suggested that a high consumption of vitamin E supplements, which mostly contain α-tocopherol, may impair γ-tocopherol bioavailability, which would explain the disappointing results of large-scale clinical trials designed to evaluate the effects of vitamin E on cardiovascular diseases (31). The significant inhibition of RRR-γ-T absorption when 40 μM RRR-α-T was added (and vice versa), together with the finding that α-tocopherol concentrations in the human gut range between 100–600 μM following the intake of a 440 mg vitamin E supplement (1), show that competition between these forms of vitamin E likely occurs in vivo. Because SR-BI is also involved in the intestinal uptake of lutein (7), a carotenoid which, like tocopherol, is an isoprenoid, it is possible that carotenoids may impair tocopherol absorption. We therefore performed competition studies between RRR-α-T or RRR-γ-T and carotenoids. These experiments showed that lutein, but not β-carotene and lycopene, impaired tocopherol absorption. This difference can be explained by the necessarily lower concentration of lycopene and β-carotene able to have been incorporated into micelles (lutein is more soluble in micelles than the two other carotenoids). These results suggest that cholesterol, carotenoids and vitamin E may compete for transport by SR-BI. This is consistent with in vivo studies which have shown that vitamin E decreases canthaxanthin absorption in the rat (32), and that diet supplementation with 400 IU α-T per day reduces serum concentrations of γ- and δ-T in humans (33).

While the physiopathological consequences of our findings remain unknown, we suggest that inter-individual variations in SR-BI expression or efficiency may explain the highly significant inter-individual variability in tocopherol absorption (34).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jean-François Landrier, Isabelle Crenon, Corinne Kreuser and Brigitte Kerfelec for their valuable comments.

Abbreviations

- RRR-α-T

RRR-α-tocopherol

- RRR-γ-T

RRR-γ-tocopherol

- DL-α-T

DL-α-tocopherol

- SR-BI

Scavenger Receptor class B type I

- CD36

Cluster Determinant 36

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- SR-BI Tg mice

mice overexpressing SR-BI

Bibliography

- 1.Borel P, Pasquier B, Armand M, Tyssandier V, Grolier P, Alexandre-Gouabau MC, Andre M, Senft M, Peyrot J, Jaussan V, Lairon D, Azais-Braesco V. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;280(1):G95–G103. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.1.G95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Traber MG. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(1):3–4. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brewer HB, Jr, Santamarina-Fojo S. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(7A):3E–11E. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis HR, Jr, Zhu LJ, Hoos LM, Tetzloff G, Maguire M, Liu J, Yao X, Iyer SP, Lam MH, Lund EG, Detmers PA, Graziano MP, Altmann SW. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(32):33586–33592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405817200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kramer W, Girbig F, Corsiero D, Pfenninger A, Frick W, Jahne G, Rhein M, Wendler W, Lottspeich F, Hochleitner EO, Orso E, Schmitz G. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(2):1306–1320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406309200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai L, Eckhardt ER, Shi W, Zhao Z, Nasser M, de Villiers WJ, van der Westhuyzen DR. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(2):253–262. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300303-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reboul E, Abou L, Mikail C, Ghiringhelli O, Andre M, Portugal H, Jourdheuil-Rahmani D, Amiot MJ, Lairon D, Borel P. Biochem J. 2005;387(2):455–461. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Bennekum A, Werder M, Thuahnai ST, Han CH, Duong P, Williams DL, Wettstein P, Schulthess G, Phillips MC, Hauser H. Biochemistry. 2005;44(11):4517–4525. doi: 10.1021/bi0484320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy E, Menard D, Suc I, Delvin E, Marcil V, Brissette L, Thibault L, Bendayan M. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(2):327–337. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goti D, Hrzenjak A, Levak-Frank S, Frank S, van der Westhuyzen DR, Malle E, Sattler W. J Neurochem. 2001;76(2):498–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolleck I, Schlame M, Fechner H, Looman AC, Wissel H, Rustow B. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27(7–8):882–890. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiefer C, Sumser E, Wernet MF, Von Lintig J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(16):10581–10586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162182899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mardones P, Strobel P, Miranda S, Leighton F, Quinones V, Amigo L, Rozowski J, Krieger M, Rigotti A. J Nutr. 2002;132(3):443–449. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Staggers JE, Hernell O, Stafford RJ, Carey MC. Biochemistry. 1990;29(8):2028–2040. doi: 10.1021/bi00460a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvini S, Charbonnier M, Defoort C, Alquier C, Lairon D. Br J Nutr. 2002;87(3):211–217. doi: 10.1079/BJNBJN2001507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chantret I, Rodolosse A, Barbat A, Dussaulx E, Brot-Laroche E, Zweibaum A, Rousset M. J Cell Sci. 1994;107(1):213–225. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jourdheuil-Rahmani D, Charbonnier M, Domingo N, Luccioni F, Lafont H, Lairon D. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;292(2):390–395. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bietrix F, Daoguang Y, Nauze M, Rolland C, Bertrand-Michel J, Coméra C, Shaak S, Barbaras R, Groen AK, Perret B, Tercé F, Collet X. J Biol Chem. 2006 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508868200. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burnichon V, Jean S, Bellon L, Maraninchi M, Bideau C, Orsiere T, Margotat A, Gerolami V, Botta A, Berge-Lefranc JL. Toxicol Lett. 2003;143(2):155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(03)00171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernier JJ, Adrian J, Vidon N. doin editeurs, Paris: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Artursson P, Karlsson J. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1991;175(3):880–885. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91647-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiyose C, Muramatsu R, Fujiyama-Fujiwara Y, Ueda T, Igarashi O. Lipids. 1995;30(11):1015–1018. doi: 10.1007/BF02536286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Traber MG, Kayden HJ. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49(3):517–526. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/49.3.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Artursson P, Karlsson J, Ocklind G, Schipper N. Epithelia cell culture: a practical appraoch. IRL Press; Oxford University Press, Oxford, England: 1995. pp. 111–133. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balazs Z, Panzenboeck U, Hammer A, Sovic A, Quehenberger O, Malle E, Sattler W. J Neurochem. 2004;89(4):939–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nieland TJ, Penman M, Dori L, Krieger M, Kirchhausen T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(24):15422–15427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222421399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nieland TJ, Chroni A, Fitzgerald ML, Maliga Z, Zannis VI, Kirchhausen T, Krieger M. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(7):1256–1265. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300358-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Traber MG, Burton GW, Hughes L, Ingold KU, Hidaka H, Malloy M, Kane J, Hyams J, Kayden HJ. J Lipid Res. 1992;33(8):1171–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner KH, Kamal-Eldin A, Elmadfa I. Ann Nutr Metab. 2004;48(3):169–188. doi: 10.1159/000079555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Violi F, Cangemi R, Sabatino G, Pignatelli P. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1031:292–304. doi: 10.1196/annals.1331.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hageman SH, She L, Furr HC, Clark RM. Lipids. 1999;34(6):627–631. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-0407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang HY, Appel LJ. J Nutr. 2003;133(10):3137–3140. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.10.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheeseman KH, Holley AE, Kelly FJ, Wasil M, Hughes L, Burton G. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19(5):591–598. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00083-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]