Abstract

The SbcCD complex and its homologues play important roles in DNA repair and in the maintenance of genome stability. In Escherichia coli, the in vitro functions of SbcCD have been well characterized, but its exact cellular role remains elusive. This work investigates the regulation of the sbcDC operon and the cellular localization of the SbcC and SbcD proteins. Transcription of the sbcDC operon is shown to be dependent on starvation and RpoS protein. Overexpressed SbcC protein forms foci that colocalize with the replication factory, while overexpressed SbcD protein is distributed through the cytoplasm.

The maintenance of genome stability is crucial for all living organisms. External as well as internal factors can cause DNA lesions that are precursors to mutation or to DNA repair. In the gram-negative eubacterium Escherichia coli, the structural maintenance of chromosome proteins, such as the SbcCD complex, plays important roles in DNA repair and in the maintenance of genome stability. Mutations in the sbcDC operon facilitate the propagation of palindrome-containing replicons (6, 14) and are associated with the increased frequency of inversion between short inverted repeats (25). SbcCD is a complex that cleaves double-strand DNA, where SbcD comprises the nuclease center. SbcC consists of ATPase domains separated by long coiled coils and modulates the nuclease activity (7). Although several activities of the E. coli SbcCD complex have been biochemically characterized, its regulation and cellular localization have remained unknown.

In the gram-positive eubacterium Bacillus subtilis, localization of the PolC protein, a subunit of the DNA polymerase III, demonstrates that a replication factory through which the DNA template would travel resides in the middle of the cell (15). Localization of the B. subtilis SbcCD complex has been studied (16, 17). Native levels of the SbcC-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) fusion protein are mostly cytoplasmic (16). However, in the presence of mitomycin C, a DNA cross-linking agent, SbcC-YFP seems to localize in the nucleoid and to colocalize with DnaX-CFP, another component of the replication factory. SbcD-GFP localized to the cytoplasm, independently of the presence of mitomycin C. Strikingly, mitomycin C induced the production of the SbcC-YFP and SbcD-GFP proteins. Another study showed the localization of overexpressed GFP-SbcC and GFP-SbcD fusion proteins (17). The GFP-SbcC fusion protein localized at a mid-cell spot in the nucleoid, displaying a pattern similar to that of subunits of the DNA polymerase III, such as DnaN or DnaX (17). Localization of overexpressed GFP-SbcD was cytoplasmic. These data would suggest that in B. subtilis, SbcC but not SbcD may be associated with the replication factory.

In E. coli, the presence of a central fixed replication factory was established by microscopy, using the SeqA fusion protein (20). This protein binds newly formed hemimethylated DNA during replication and localizes at the replication fork. SeqA has been shown to be closely associated with the replication factory (9).

In E. coli, starvation, entry into the postexponential phase during growth, and other conditions of stress induce the RpoS sigma factor (σS). The σS factor could be directly or indirectly involved in the regulation of 10% of E. coli genes (29). Regulation of the σS is complex and involves all stages of its production (10). Notably, the Hfq protein helps rpoS translation, whereas the ClpXP protease is responsible for degradation of the RpoS protein.

This work investigates SbcCD regulation and localization in E. coli. Expression of the sbcDC operon is shown to be dependent on starvation and RpoS. Localization of SbcCD can be detected only when proteins are overexpressed. Overexpressed SbcC is associated with the replication forks, while overexpressed SbcD is a cytoplasmic protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, bacterial strains, primers, and media.

Table 1 lists the plasmids, bacterial strains, and primers used. Bacteria were grown at 37°C with agitation in either LB (1% Bacto tryptone, 0.5% Bacto yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl, and 2 mM NaOH) or M9 medium (50 mM Na2HPO4, 22 mM KH2PO4, 8.5 mM NaCl, and 2 mM NH4Cl, supplemented with 0.1 M CaCl2, 1 M MgSO4, and 0.2% glycerol). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 mg/liter; chloramphenicol, 50 mg/liter; and kanamycin (Km), 50 mg/liter. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was used at 50 μM. Arabinose was used at 0.001% (wt/vol).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids, bacterial strains, and primers

| Plasmid, strain, or primer | Relevant propertiesb | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| p18seqA | pLAU18 derivative plasmid carrying a SeqA-eYFP C-terminal fusion under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter (PBAD); Ampr | This work |

| p207NsbcC | pDSW207 derivative carrying a GFP-SbcC N-terminal protein fusion; Ampr | This work |

| p207NsbcD | pDSW207 derivative carrying a GFP-SbcD N-terminal protein fusion; Ampr | This work |

| pDSW207 | pTrc99A derivative containing a gfp-MCS region controlled by a downregulated trc promoter (mutation in −35 box); Ampr | 30 |

| pLAU18 | pUC18 derivative permitting the construction of eYFP fusion proteins under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter (PBAD); carries the araC gene; Ampr | 13 |

| pRSETBDsRed | pRSETB derivative carrying the gene encoding the DsRed protein; Ampr | 5 |

| pseqAred | p18seqA derivative vector carrying the dsRed gene in place of eyfp; Ampr | This work |

| pseqAredKm | pseqAred derivative vector, where the bla gene is disrupted by the aph gene; Kmr | This work |

| pTOF24 | pSC101-based vector; repA(Ts) with a sacB gene conferring sucrose sensitivity and aph from pUC4K; Cmr, Kmr, Ts, Sucs | 18 |

| pTOF30 | Plasmid containing an FLK2 cassette (lacZ aph); Ampr, Kmr | 18 |

| pTOF24ΔclpX | pTOF24 derivative containing two fused PCR fragments corresponding to the beginning and the end of clpX, in place of the aph gene; Cmr, Ts, Sucs | This work |

| pTOFNGFPsbcC | pTOF24 derivative containing a GFP-SbcC N-terminal protein fusion and the ′sbcD sequence, permitting its integration at the locus in the E. coli chromosome; Cmr, Ts, Sucs | This work |

| pTOFNGFPsbcD | pTOF24 derivative containing a GFP-SbcD N-terminal protein fusion, PsbcDC, and part of the phoB gene sequence, permitting its integration at the locus in the E. coli chromosome; Cmr, Ts, Sucs | This work |

| pTOFsbcDC | pTOF24 derivative containing two fused PCR fragments corresponding to the beginning of the sbcD and the end of the sbcC genes, in place of the aph gene; Cmr, Ts, Sucs | This work |

| pTOFsbcDCK2 | pTOFsbcDC derivative containing an FLK2 cassette from pTOF30; Cmr, Kmr, Ts, Sucs | This work |

| E. coli strains | ||

| BW27784 | lacIqrrnB3ΔlacZ4787 hsdR514 DE(araBAD)567 DE(rhaBAD)568 DE(araFGH) Φ(ΔaraEp PCP18-araE) | 11 |

| DL1649 | MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔsbcDC PsbcDC-lacZ-aph | This work |

| DL1718 | MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔsbcDC rpoS359::Tn10 PsbcDC-lacZ-aph | This work |

| DL1796 | MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔsbcDC ΔclpX PsbcDC-lacZ-aph | This work |

| DL1913 | MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔclpX | This work |

| DL2478 | MG1655 att::207NGFP-sbcC | This work |

| DL2479 | MG1655 att::207NGFP-sbcD | This work |

| DL2532 | MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔclpX GFP-sbcC | This work |

| DL2533 | MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) GFP-sbcC | This work |

| DL2535 | MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) GFP-sbcD | This work |

| DL2739 | BW27784 att::207NGFP-sbcC | This work |

| DL3117 | MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) rpoS359::Tn10 GFP-sbcC | This work |

| EDCM367 | MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) | 18 |

| MG1655 | F− λ−ilvG rfb-50 rph-1 | 2 |

| RH90 | MC4100 rpoS359::Tn10 | 12 |

| Primersa | ||

| clpXflank F1 | AAAAAGTCGACGCAGGGGCAAAAGGTAAAC | This work |

| clpXflank F2 | GGCTCAGGCAAATGGAAGACGTCGAAAAAGTGG | This work |

| clpXflank R1 | CGACGTCTTCCATTTGCCTGAGCCATCTTT | This work |

| clpXflank R2 | AAAAACTGCAGCGCTTCCAGACAACGGATAG | This work |

| dsRED-XhoI | AAAAACTCGAGTTGGCCTCCTCCGAGGACGTCATCAAG | This work |

| dsRED-HindIII | AAAAAAAGCTTTTAGGCGCCGGTGGAGTGG | This work |

| Km-ScaI-F | AAAAAAGTACTCCACGTTGTGTCTCAAAATC | This work |

| Km-ScaI-R | AAAAAAGTACTCCGTCAAGTCAGCGTAATG | This work |

| lacZ-chi-seq-R | TTT TTA TCG CCA ATC CAC ATC | This work |

| NtermGFP-SbcC1 | AAAAACAATTGAACAACAACATGAAAATTCTCAGCCTGCG | This work |

| NtermGFP-SbcC2 | AAAAAAAGCTTTTATTTCACTGCAAACGTAC | This work |

| NtermGFP-sbcC5 | AAAAACTCGAGCCCCATTCCACTGAGTTTTG | This work |

| NtermGFP-sbcC6 | TTCTCCTTTACTCATGCTTCGTGTTCTCCGGC | This work |

| NtermGFP-sbcC7 | ACACGAAGCATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAAC | This work |

| NtermGFP-sbcC8 | AAAAAGTCGACCTTTGTCGGCGAGAATTTTG | This work |

| NtermGFP-SbcD1 | AAAAAGAATTCAACAACAACATGCGCATCCTTCACACCTC | This work |

| NtermGFP-SbcD2 | AAAAAAAGCTTTCATGCTTCGTGTTCTCCGG | This work |

| NtermGFP-SbcD6 | TTCTCCTTTACTCATAACGGTTCCCTGGCG | This work |

| NtermGFP-SbcD7 | GGAACCGTTATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAAC | This work |

| SeqA_F | TTTCCATGGATGAAAACGATTGAA | This work |

| SeqA_R | TTTCTCGAGGATAGTTCCGCAAAC | This work |

| sbcC1-4 | AAAAAGTCGACGTGAGTAGCGGCTGGAAAAG | This work |

| sbcDC2-1 | AAAAACTGCAGGGCCAGGGTTCATTCAGTT | This work |

| sbcDC2-2 | CACACCGAGCGGCCGCAGCAGCCAGTCAAGAAAAGC | This work |

| sbcDC2-3 | TGGCTGCTGCGGCCGCTCGGTGTGATTAGCCACGTA | This work |

| sbcDCnd4-4 | AAAAAGTCGACCGCCTGGCTGGTAATAATG | This work |

Primers are shown in a 5′-3′ direction.

Abbreviations: Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant; Kmr, kanamycin resistant; Ts, replication of the plasmid is temperature sensitive; Sucs, sucrose sensitive. Restriction sites used for cloning are underlined, ATG start codons are double underlined, and sequences used for PCR-mediated coupling are indicated in bold type.

DNA techniques.

Procedures for DNA purification, restriction, ligation, agarose gel electrophoresis, and transformation of competent E. coli cells were carried out as described by Sambrook and collaborators (24). PCR was carried out as described by van Dijl et al. (27). Enzymes were from New England Biolabs or Roche Molecular Biochemicals.

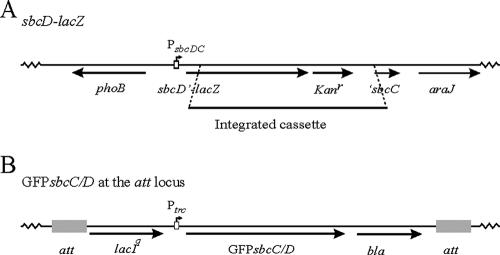

The E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔsbcDC PsbcDC-lacZ-aph reporter strain (DL1649; Fig. 1A) was constructed by replacement of the sbcDC operon with a DNA fragment containing the lacZ gene and the kanamycin resistance gene aph. Two amplified fragments flanking the sbcDC operon were ligated, after PCR-mediated coupling, into the chromosomal integration-and-excision plasmid pTOF24 (18). The upstream fragment of 450 nucleotides was amplified from E. coli MG1655 using primers sbcDC2-1 and sbcDC2-2. The downstream fragment of 466 nucleotides was amplified from E. coli MG1655 DNA using primers sbcDC2-3 and sbcC1-4. The 892-nucleotide-coupled fragment was cloned between the PstI and SalI sites of plasmid pTOF24, resulting in the kanamycin-sensitive plasmid pTOFsbcDC. The FLK2 cassette, carrying lacZ and aph genes, was isolated from the plasmid pTOF30 by restriction using the NotI enzyme and inserted into the cleaved plasmid pTOFsbcDC, resulting in pTOFsbcDCK2. This temperature-sensitive plasmid was introduced into the E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) strain (EDCM367), with selection for chloramphenicol resistance. Finally, the gene replacement by chromosomal integration and excision was carried out as described by Merlin and collaborators (18). Correct excision of the sbcDC operon and integration of the FLK2 cassette were verified by selection for kanamycin-resistant colonies and PCR and by sequencing using primers sbcDC2-1 and lacZ-chi-seq-R. The absence of SbcCD activity was confirmed by using a phage lambda plating test (6, 8).

FIG. 1.

Construction of mutant strains. (A) Construction of the sbcD-lacZ reporter strain (DL1649). Shown is a schematic representation of the sbcDC region containing the PsbcDC-lacZ reporter fusion. Part of the sbcDC operon was removed, and the cassette containing the lacZ and the kanamycin resistance genes was placed under the control of the sbcDC promoter region and fused to the beginning of the sbcD gene. sbcD′, 3′ truncated sbcD gene; Kanr, kanamycin resistance gene; ′sbcC, 5′ truncated sbcC gene. (B) Construction of functional gfp-sbcC/D reporter strains (DL2478 and DL2479). Shown is a schematic representation of the att region containing the gfp-sbcC or gfp-sbcD reporter fusion. The gfp-sbcC/D fusion was placed under the control of the IPTG-inducible trc promoter region, and the protein fusion to the GFP was N terminal. bla, ampicillin resistance gene.

The E. coli MG1655 att::207NGFP-sbcC (DL2478; Fig. 1B) and E. coli BW27784 att::207NGFP-sbcC (DL2739) strains were constructed by the insertion of an in-frame fusion of the gfp and sbcC genes under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter into the att loci of E. coli MG1655 and E. coli BW27784, respectively. Insertions were carried out using the p207NsbcC plasmid, as described by Boyd and collaborators (3). To construct the p207NsbcC plasmid, the sbcC gene was amplified using primers NtermGFP-SbcC1 and NtermGFP-SbcC2 (3,175 nucleotides). Notably, the NtermGFP-SbcC1 primer includes a sequence introducing an ELNNN polypeptide linker between the green fluorescent protein (GFP) and the SbcC protein. The resulting PCR fragment was digested using enzymes MfeI and HindIII and cloned between the EcoRI and HindIII sites of plasmid pDSW207 (30).

The E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) GFP-sbcC strain (DL2533) was constructed by insertion of the gfp gene in frame with the sbcC gene using the pTOFNGFPsbcC plasmid. Two amplified fragments were coupled by crossover PCR and ligated into the chromosomal integration-and-excision plasmid pTOF24 (18). The first fragment of 506 nucleotides was amplified from E. coli MG1655 DNA using primers NtermGFP-sbcC5 and NtermGFP-sbcC6. The second fragment of 1,134 nucleotides was amplified from p207NsbcC, using primers NtermGFP-sbcC7 and NtermGFP-sbcC8. The 1,616-nucleotide-coupled fragment was cloned between the XhoI and SalI sites of plasmid pTOF24, resulting in the kanamycin-sensitive plasmid pTOFNGFPsbcC. This temperature-sensitive plasmid was introduced into the E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) strain (EDCM367) with selection for chloramphenicol resistance, and the gene replacement by chromosomal integration and excision was carried out as described by Merlin and collaborators (18). Correct integration of the gfp gene was verified by PCR using primers NtermGFP-sbcC5 and NtermGFP-sbcC8. The activity of the GFP-SbcC-SbcD complex was tested using the phage lambda plating test (6, 8).

The E. coli MG1655 att::207NGFP-sbcD strain (DL2479; Fig. 1B) was constructed by insertion of an in-frame fusion of the gfp and sbcD genes under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter at the E. coli MG1655 att locus. The insertion was carried out using the p207NsbcD plasmid, as described by Boyd and collaborators (3). To construct the p207NsbcD plasmid, the sbcD gene was amplified using primers NtermGFP-SbcD1 and NtermGFP-SbcD2 (1,231 nucleotides). Notably, the NtermGFP-SbcD1 primer includes a sequence introducing an EFNNN polypeptide linker between the GFP and SbcD proteins. The resulting PCR fragment was cloned between the EcoRI and HindIII sites of plasmid pDSW207 (30).

The E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) GFP-sbcD strain (DL2535) was constructed by insertion of the gfp gene in frame with the sbcD gene using the pTOFNGFPsbcD plasmid. Two amplified fragments were ligated, after PCR-mediated coupling, into the chromosomal integration-and-excision plasmid pTOF24 (18). The first fragment of 355 nucleotides was amplified from E. coli MG1655 DNA using primers sbcDC2-1 and NtermGFP-sbcD6. The second fragment of 1,175 nucleotides was amplified from p207NsbcD, using primers NtermGFP-sbcD7 and sbcDCnd4-4. The 1,506-nucleotide-coupled fragment was cloned between the SalI and PstI sites of plasmid pTOF24, resulting in the kanamycin-sensitive plasmid pTOFNGFPsbcD. This temperature-sensitive plasmid was introduced into the E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) strain (EDCM367), with selection for chloramphenicol resistance, and the gene replacement by chromosomal integration and excision was carried out as described by Merlin and collaborators (18). Correct integration of the gfp gene was verified by PCR using primers sbcDC2-1 and sbcDCnd4-4. The activity of the SbcC-GFP-SbcD complex was tested using the phage lambda plating test (6, 8).

The E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔsbcDC rpoS359::Tn10 PsbcDC-lacZ-aph (DL1718) and E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) rpoS359::Tn10 GFP-sbcC (DL3117) reporter strains were constructed by transfer of the rpoS359::Tn10 mutation from the RH90 strain into strains MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔsbcDC PsbcDC-lacZ-aph (DL1649) and MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) GFP-sbcC (DL2533), respectively, using the P1 transduction technique (19).

The E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔsbcDC ΔclpX PsbcDC-lacZ-aph (DL1796) and E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔclpX (DL1913) reporter strains were constructed by deletion of the clpX gene from the chromosomes of the MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔsbcDC PsbcDC-lacZ-aph (DL1649) and MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) (EDCM367) strains, using the pTOF24ΔclpX plasmid. Two amplified fragments flanking the clpX gene were coupled by crossover PCR and ligated into the chromosomal integration-and-excision plasmid pTOF24 (18). The upstream fragment of 450 nucleotides was amplified from E. coli MG1655 DNA using primers clpXflankF1 and clpXflankR1. The downstream fragment of 442 nucleotides was amplified from E. coli MG1655, using primers clpXflankF2 and clpXflankR2. The 870-nucleotide-coupled fragment, after PCR-mediated coupling of these two fragments, was cloned between the SalI and PstI sites of plasmid pTOF24, resulting in the kanamycin-sensitive pTOF24ΔclpX plasmid. This temperature-sensitive plasmid was introduced into E. coli strains MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔsbcDC PsbcDC-lacZ-aph (DL1649) and MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) (EDCM367), with selection for chloramphenicol resistance, and the gene replacement by chromosomal integration and excision was carried out as described by Merlin and collaborators (18). Correct excision of the clpX gene was verified by PCR using primers clpXflankF1 and clpXflankR2.

The E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔclpX GFP-sbcC (DL2532) strain was constructed using the pTOFNGFPsbcC plasmid. This temperature-sensitive plasmid was introduced into the E. coli strain with selection for chloramphenicol resistance, and the gene replacement by chromosomal integration and excision was carried out as described by Merlin and collaborators (18). Correct integration of the gfp gene was verified by PCR. The activity of the GFP-SbcC-SbcD complex was tested using the phage lambda plating test (6, 8).

To construct the pseqAredKm plasmid, the seqA gene was amplified from E. coli MG1655 DNA using primers SeqA_F and SeqA_R. The 560-nucleotide fragment was cloned between the NcoI and XhoI sites of plasmid pLAU18, resulting in plasmid p18seqA, which encoded a C-terminal SeqA-eYFP protein fusion. Subsequently, the gene encoding the DsRed protein was amplified from plasmid pRSETBDsRed DNA (5), using primers dsRED-XhoI and dsRED-HindIII. The 700-nucleotide fragment was cloned in place of the eyfp gene, between the XhoI and HindIII sites of plasmid p18seqA, resulting in pseqAred. Notably, the dsRED-XhoI primer includes a sequence introducing an LEL polypeptide linker between the SeqA and DsRed proteins. Finally, the kanamycin resistance gene was amplified from pTOF24, using primers Km-ScaI-F and Km-ScaI-R. The 837-nucleotide fragment was cloned into the pseqAred plasmid, using ScaI. The resulting plasmid pseqAredKm is ampicillin sensitive and kanamycin resistant.

β-Galactosidase activity assay.

To measure β-galactosidase activities, overnight cultures were diluted in fresh medium, and samples were taken at regular intervals for optical density (OD) readings at 600 nm and β-galactosidase activity determinations. The β-galactosidase assay and the calculation of β-galactosidase units (Miller units, nmol/OD600/min) were performed as described by Miller (19), using the following formula for calculation of the β-galactosidase activity: (OD420 × 1.7)/(0.0045 × reaction time in min × OD600 × volume of cells). Although some differences were observed for absolute β-galactosidase activities, the ratios between these activities in the various strains tested were largely constant. A ratio of about 1.5 was generally reproducible.

Western blotting.

E. coli cultures were grown, and the amount of cells corresponding to an OD600 of 1 was separated from the growth medium by centrifugation, resuspended in 40 μl of fresh medium and 20 μl of 3× sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer plus dithiothreitol (Biolabs), and boiled for 10 min. These preparations (10 μl) were run on a gradient Nu-page 4 to 12% bis Tris gel (Invitrogen), and electrophoresis was performed in morpholinepropanesulfonic acid buffer, using an XCell SureLock minicell system (Invitrogen), according to manufacturer's instructions. A SeeBlue Plus2 prestained standard was used as a marker of protein size (Invitrogen original membranes were used as templates [see Fig. 2 and 3]). After proteins were separated, they were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Biotrace NT), using a wet transfer Western blot apparatus (Bio-Rad) in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 200 mM glycine, and 20% methanol). Proteins were detected with GFP-specific rabbit antibodies (1/5,000 dilution; Invitrogen) and horseradish peroxidase anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugates (1/5,000 dilution; Amersham) and visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence solution.

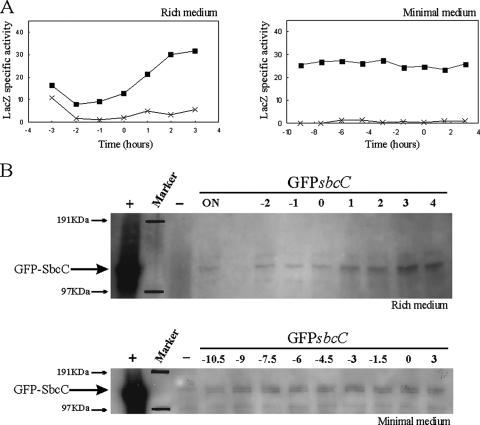

FIG. 2.

Analyses of sbcDC transcription and SbcC protein level as a function of time and growth medium. (A) The transcriptional sbcD-lacZ gene fusion schematically shown in Fig. 1A was used to determine the time course of sbcDC expression in cells grown at 37°C in either LB (left panel) or supplemented M9 (right panel) medium. The strains used for the analyses were E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) (crosses; EDCM367) and E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔsbcDC PsbcDC-lacZ-aph (closed squares; DL1649). Samples for the determination of β-galactosidase activities (indicated in nmol/min/OD600) were collected at defined times. Time 0 indicates the transition point between exponential and postexponential growth phases determined by a change in the slope of the growth curve. (B) GFP-SbcC fusion was used to determine by Western blotting the time course of SbcC protein levels in cells grown at 37°C in either LB or supplemented M9 medium. The position of the fusion protein is indicated. The protein marker positions were marked on the film from positions shown on the membrane. Time 0 indicates the transition point between exponential and postexponential growth phases. Times are indicated in hours. ON indicates overnight cultures. Strains used for the analyses were E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) (EDCM367; −, overnight culture as negative control), E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) GFP-sbcC (DL2533; GFP-sbcC), and E. coli MG1655 att::207NGFP-sbcC, grown in the presence of 50 μM of IPTG (DL2478; +, overnight culture as positive control).

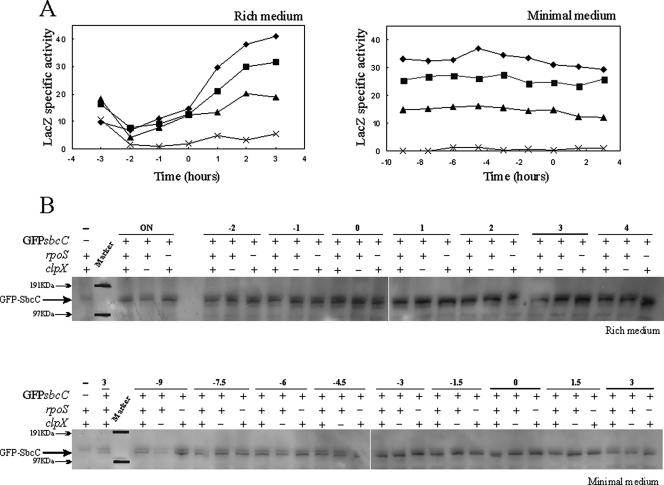

FIG. 3.

Effect of the rpoS or clpX mutation on sbcDC transcription and SbcC protein level. (A) The transcriptional sbcD-lacZ gene fusion, schematically shown in Fig. 1A, was used to determine the time course of sbcDC expression in the presence and absence of the rpoS or clpX gene in cells grown at 37°C in either LB (left panel) or supplemented M9 (right panel) medium. Strains used for the analyses were E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) (crosses; EDCM367), E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔsbcDC PsbcDC-lacZ-aph (closed squares; DL1649), E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔsbcDC rpoS359::Tn10 PsbcDC-lacZ-aph (closed triangles; DL1718), and E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔsbcDC ΔclpX PsbcDC-lacZ-aph (closed diamonds; DL1796). Samples for the determination of β-galactosidase activities (indicated in nmol/min/OD600) were collected at defined times. Time 0 indicates the transition point between the exponential and postexponential growth phases determined by a change in the slope of the growth curve. (B) GFP-SbcC fusion was used to determine by Western blotting the time course of SbcC protein level in the presence and absence of RpoS or ClpX protein in cells grown at 37°C in either LB (top panel) or supplemented M9 (lower panel) medium. The position of the fusion protein is indicated. The protein marker positions were marked on the film from positions shown on the membrane. Time 0 indicates the transition point between the exponential and postexponential growth phases. Times are indicated in hours. ON indicates overnight cultures. The strains used for the analyses were E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) (EDCM367; −, overnight culture as negative control), E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) GFP-sbcC (DL2533), E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) ΔclpX GFP-sbcC (DL2532), and E. coli MG1655 Δ(Plac-lacZY) rpoS359::Tn10 GFP-sbcC (DL3117).

Fluorescence microscopy.

Cells were grown at 37°C in LB or supplemented M9 medium. When indicated, 50 μM of IPTG was added to the medium (at the beginning of the day's growth for samples taken at the mid-exponential growth phase and the previous day for samples taken after an overnight culture). On the other hand, 0.001% (wt/vol) of arabinose was added to the overnight culture as well as to the day culture. Live cells were visualized on a 1% agarose-coated slide. GFP or red fluorescent protein (RFP) fluorescence was detected using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 fluorescence microscope with a GFP filter or a 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)/fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/tetramethyl rhodamine isocyanate (TRITC) filter set (catalog number 82101m; Semrock). Images were captured with a Photometrics cool-SNAP HQ charge-coupled device camera. Optical section images were collected at 150-nm intervals, deconvolved using Autovisualize+Autodeblur software (three-dimensional adaptive point spread function [blind] deconvolution), and analyzed using MetaMorph version 6 3r2 software (Molecular Devices).

RESULTS

Study of the transcription of the sbcDC operon.

In order to study the transcription of the sbcDC operon, a transcriptional sbcD-lacZ fusion was constructed in place of the native operon, inactivating both genes (DL1649; Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 2A, sbcDC transcriptional level was generally low and dependent on the growth medium (Fig. 2A). In rich medium (Fig. 2A, LB medium, left panel), sbcDC transcription changed as a function of growth. The transcription level was very low during exponential phase and then increased about threefold during early postexponential phase, before stabilizing at 2 h into the stationary phase. The level of sbcDC transcription remained low when cells were kept at exponential phase growth by regular dilution of the culture (data not shown). In minimal medium (supplemented M9 medium), the sbcDC transcription was constitutive (Fig. 2A, right panel). Overproduction of the SbcCD complex had no effect on sbcDC transcription, suggesting that the operon is not autoregulated (data not shown). Finally, the sbcDC transcription level was not significantly affected by a mutation in the lexA or the recA gene, indicating that the operon is not a member of the SOS regulon (data not shown).

Study of SbcC/D protein levels.

Detection of native levels of the SbcC and SbcD proteins by using specific antibodies was unsuccessful, so GFP-sbcC and GFP-sbcD fusions were constructed at the native locus (for strains DL2533 and DL2535, respectively), and protein levels were measured by Western blotting using GFP antibodies. The normal activities of the GFP-SbcC and GFP-SbcD fusion proteins were confirmed by using a phage lambda plating test (data not shown; 6, 8). As displayed in Fig. 2B, the level of GFP-SbcC protein was generally low. Under the conditions tested, GFP-SbcC was present in cells grown in both media. GFP-SbcD was visible when cells were grown in rich medium but was barely detectable when cells were grown in minimal medium (data not shown). Surprisingly, protein levels of GFP-SbcC and GFP-SbcD were not significantly affected by the stage of cellular growth, suggesting that in rich medium, protein levels do not follow the transcription pattern (Fig. 2B and data not shown). Nevertheless, GFP-SbcC and GFP-SbcD proteins were present in the stationary phase as predicted by the transcriptional analyses.

Effect of RpoS on sbcDC transcription and protein levels.

To determine whether the RpoS sigma factor is responsible for the increase of sbcDC transcription during postexponential phase, an rpoS disruption was introduced into the strain containing the sbcD-lacZ transcriptional fusion (DL1718). As shown in Fig. 3A, the sbcDC transcriptional level was 1.5-fold lower in those cells that lacked RpoS, growing in minimal medium or during the postexponential phase in rich medium (Fig. 3A). No significant differences in sbcDC transcription were observed during the exponential phase of cells grown in rich medium. Strikingly, in the absence of RpoS, the sbcDC transcriptional level in cells grown in rich medium still increased by 1.5-fold between the exponential and the postexponential phases, possibly indicating the presence of an additional regulation system. To confirm the involvement of RpoS in sbcDC transcription, the clpX gene was inactivated in the strain containing the sbcD-lacZ transcriptional fusion (DL1796). In the absence of ClpX, cells contained more RpoS sigma factor, and sbcDC transcription increased about 1.5-fold in cells grown in minimal medium or during the postexponential phase in rich medium (Fig. 3A). Notably, in rich medium, the level of sbcDC transcription in the rpoS clpX double mutant was similar to the level in the rpoS single mutant (data not shown). Finally, inactivation of the hfq gene decreased sbcDC transcription to a level comparable to that obtained in the absence of rpoS (data not shown).

Levels of SbcC and SbcD proteins were studied by Western blotting as a function of time and in the absence of RpoS or ClpX protein. As shown in Fig. 3B, GFP-SbcC protein levels, in rich or minimal medium, were similar to that in wild-type cells and in cells of strains carrying mutations in either the rpoS or the clpX gene. Furthermore, levels of GFP-SbcD were comparable in the presence or absence of the RpoS or the ClpX protein, when cells were grown in rich medium, while the GFP-SbcD protein was almost undetectable when cells were grown in minimal medium (data not shown).

Localization of GFP-SbcC/D.

The GFP-sbcC and GFP-sbcD fusions used for the determination of protein levels by Western blotting were under the control of the native sbcDC promoter. Under these conditions, the native level of proteins was too low to permit the visualization of GFP-SbcC or GFP-SbcD by microscopy (data not shown). Strikingly, the addition of mitomycin C to the growth medium or the introduction of a palindrome into the chromosome did not permit the visualization of an eventual GFP-SbcC/D localization (data not shown). New constructs were made in order to obtain higher levels of expression of SbcCD by placing the GFP-sbcC or the GFP-sbcD fusion gene under the control of the IPTG-inducible Ptrc promoter in the att locus of the E. coli chromosome (strains DL2478 and DL2479, respectively). Normal activities of the inducible GFP-SbcC and GFP-SbcD fusion proteins were confirmed by using the phage lambda plating test (data not shown; 6, 8). Western blotting analyses of strains containing these fusions indicated the presence of some degradation products only in those cells growing at late postexponential phase and induced by the addition of IPTG (after overnight culture; data not shown).

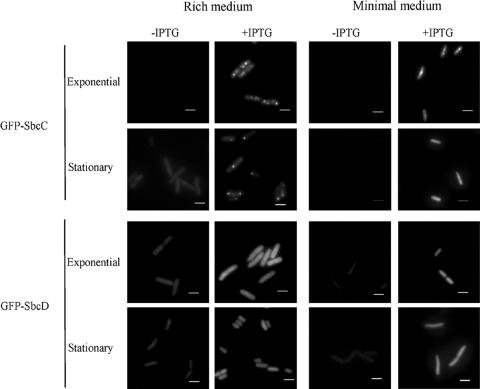

Localization of the GFP-SbcC and GFP-SbcD proteins using these new constructs was determined under different conditions by using microscopy (Fig. 4). In the absence of IPTG, cell fluorescence was very low, close to the background level, and no localization was perceptible. After the addition of IPTG, foci were visible in exponential phase cells expressing the GFP-SbcC fusion protein. When cells were grown in minimal medium, most of these cells displayed either a mid-cell focus or two foci, one located at one-quarter and the second at three-quarters of the cell length. More foci with different intensity levels were visible in cells grown in rich medium. During stationary phase, overproduction of GFP-SbcC in cells grown in rich medium led to the presumed artifactual accumulation of fusion proteins at cellular poles, whereas when cells were grown in minimal medium, GFP-SbcC seemed to be evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm. Interestingly, the GFP-SbcC cellular localization was independent of the presence and the level of the SbcD protein (data not shown). Conversely, when IPTG was added to cells expressing the functional GFP-SbcD fusion, fluorescence was evenly distributed throughout their cytoplasm, independently of the growth medium or the growth phase (Fig. 4). Finally, the cytoplasmic distribution of GFP-SbcD subsisted in the absence of the SbcC protein (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Localization of GFP-SbcC/D fusion proteins as a function of time and growth medium. E. coli MG1655 att::207NGFP-sbcC (DL2478; GFP-SbcC) and E. coli MG1655 att::207NGFP-sbcD (DL2479; GFP-SbcD) were grown at 37°C in either LB (left panels) or supplemented M9 (right panels) medium in the presence or absence of 50 μM of IPTG. Cells were grown either until mid-exponential growth phase or until stationary phase (overnight) and then visualized on a 1% agarose-coated slide by fluorescence microscopy using a GFP filter. The calibration bar indicates 2 μm.

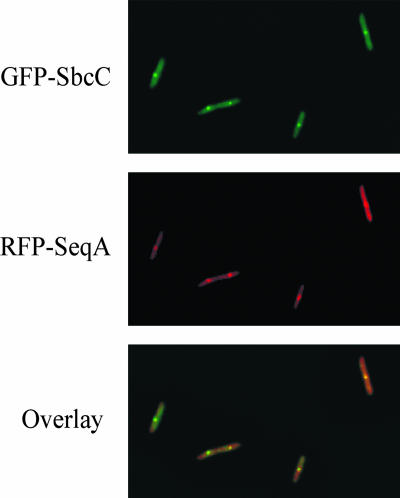

Colocalization of the GFP-SbcC and RFP-SeqA proteins.

The localization of GFP-SbcC in exponential phase cells grown in minimal medium was similar to the documented localization of the cell replication factory (20). To determine whether the SbcC protein might be associated with the replication factory, GFP-SbcC fusion protein localization was studied in association with a protein that binds DNA at replication forks, SeqA. The pseqAredKm plasmid carrying an arabinose-inducible RFP-SeqA fusion protein was introduced into a strain containing the IPTG-inducible GFP-sbcC fusion gene (strain DL2739). Notably, homogeneous expression from the arabinose-inducible system was ensured by using a specific background strain (BW27784 [11]). Colocalization of these two fluorescent proteins was studied in 777 exponential phase cells grown in minimal medium, distributed in three independent experiments. Notably, 56% of these cells displayed one GFP-SbcC focus, and 34% displayed several foci; so, only 10% of the cells showed a dispersed cytoplasmic localization of GFP-SbcC. On the other hand, 48% of cells displayed one RFP-SeqA focus, and 20% displayed several foci; so, 32% of cells showed a dispersed RFP-SeqA cytoplasmic localization. The fluorescence of the RFP-SeqA fusion protein was low, and foci were difficult to visualize, probably explaining the fact that cells seem to have less RFP-SeqA foci than GFP-SbcC foci. Interestingly, in the 510 cells displaying at least one focus of each GFP-SbcC and RFP-SeqA fusion protein, colocalization was observed in 94% of cells, with 79% of foci showing colocalization. Figure 5 illustrates some GFP-SbcC/RFP-SeqA colocalizations. This result suggests that GFP-SbcC and RFP-SeqA are closely associated.

FIG. 5.

Colocalization of GFP-SbcC and RFP-SeqA fusion proteins. E. coli BW27784 att::207NGFP-sbcC carrying the pseqAredKm plasmid (DL2739 plus pseqAredKm) was grown at 37°C in supplemented M9 medium in the presence of 50 μM of IPTG and 0.001% of arabinose until mid-exponential growth phase. Cells were visualized on a 1% agarose-coated slide by fluorescence microscopy using a DAPI/FITC/TRITC filter set.

DISCUSSION

This work presents, for the first time in E. coli, a study of the SbcCD regulation and localization. The transcription of the sbcDC operon is induced in an RpoS-dependent manner when cells are under starvation conditions or at postexponential phase in rich medium. However, for an unknown reason, the SbcC and SbcD protein levels do not seem to follow the transcription level. The natural levels of SbcC and SbcD are low, and GFP fusion proteins needed to be overexpressed to be visualized. Surprisingly, the two proteins do not colocalize as SbcC is associated with the replication factory, and SbcD is dispersed throughout the cytoplasm.

The action of RpoS on sbcDC transcription is probably indirect as the effect is significant but low, and the sbcDC promoter does not contain a σS-specific consensus sequence (29). On the other hand, the sbcDC promoter presents a perfect −10 region for the housekeeping σ70 factor (21). To work efficiently, the σ70 factor also needs a −35 region, which is absent from the sbcDC promoter. However, the sbcDC promoter seems to display a proximal site of an UP element consensus sequence that can bind the α subunit of RNA polymerase and help to stimulate transcription of the operon in the absence of a −35 box (26). Altogether, these observations could explain the low level of transcription of the sbcDC operon. Notably, the effect of RpoS on sbcDC transcription is probably too small to have been detected in previous studies using general methods such as DNA array analysis or random lacZ fusion mutagenesis (23, 28, 29). The fact that RpoS does not act directly on the sbcDC promoter suggests the presence of another regulatory system. Similarly, RpoS does not seem to totally control sbcDC transcription, as the operon expression still increases when rpoS mutant cells enter stationary phase. Random mutagenesis was unsuccessfully employed to investigate the identity of this potential regulator (data not shown). The unfound regulatory system might be essential or not be a protein, or the screen employed was not sensitive enough.

Surprisingly, GFP-SbcC and GFP-SbcD protein levels did not reflect the transcription pattern of the operon. Western blotting of GFP fusion proteins might not have been sensitive enough to detect the small differences seen in transcriptional levels, or the fusions might affect the stability of the proteins. Another explanation could be the presence of an additional SbcCD regulation at the mRNA or protein level. There are no published studies on the regulation of the sbcDC mRNA in E. coli. General studies of protein-protein interactions in E. coli found only one protease, ClpA, that has a potential interaction with SbcC (1, 4). However, this interaction was not validated, and ClpA did not appear to interact with the SbcD protein.

The presence of SbcCD at stationary phase is unexpected as the function of the proteins has been associated with DNA repair in the context of replication. This work suggests that SbcCD must have some as-yet unknown function in the stationary phase or in the exit from stationary phase.

The SbcC protein seems to localize at replication forks, whereas SbcD seems to be evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm. This suggests either that SbcC and SbcD can function independently of each other or that the regulation of activity is achieved by ensuring that the majority of the two proteins are not associated at any one time. The function of SbcC could be to recognize an SbcD substrate and modulate the nuclease activity of SbcD. SbcC might constantly check the replication fork for misfolded DNA and associate with SbcD only when DNA repair is necessary. SbcD action might require too small an amount of protein or might be too quick to be visualized by microscopy.

Interestingly, overproduced SbcC and SbcD proteins in E. coli and B. subtilis localize in similar ways, but the localization and regulation of the natural level of protein are different between the two organisms (16, 17). A native level of SbcC localized as discrete foci in 2% of B. subtilis cells but could not be visualized in E. coli (16). Additionally, the SbcC and SbcD protein levels in B. subtilis were induced when mitomycin C was added to the cells, while this drug had no effect on E. coli sbcDC transcription (16; data not shown). After the addition of mitomycin C, up to 40% of B. subtilis cells displayed SbcC foci, whereas no SbcC focus was visible in E. coli cells (data not shown). The presence of foci at a natural level of SbcC in B. subtilis but not in E. coli could be explained by a higher production of SbcC protein in B. subtilis than in E. coli. Notably, in the two organisms, overexpressed SbcC protein localizes as does native SbcC in B. subtilis. Therefore, SbcC might always localize at the replication fork, but the natural level of the protein is too low to be seen by microscopy in E. coli. The addition of mitomycin C in B. subtilis culture increases the SbcC protein level, permitting the visualization of more foci. The differences in SbcCD regulation between the two organisms could be explained by a different function of the complex. Interestingly, B. subtilis but not E. coli contains proteins that are involved in the nonhomologous end-joining DNA repair pathway (31), and SbcCD homologues in eukaryotes may play a role in this pathway (22).

In conclusion, this work increases the understanding of SbcCD in E. coli by investigating its regulation and localization. However, the exact role of this complex is still to be revealed and seems to be variable in different organisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an MRC grant. Z.T. was supported by the Darwin Trust.

We thank Sidney R. Kushner for providing the hfq mutant strain, Irine Prastio for providing the pRSETBDsRed plasmid, David Bates and Martin White for technical help with microscopy, Federica Andreoni and Carine Meignin for technical help with Western blotting, and John Eykelenboom for stimulating discussion and critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arifuzzaman, M., M. Maeda, A. Itoh, K. Nishikata, C. Takita, R. Saito, T. Ara, K. Nakahigashi, H.-C. Huag, A. Hirai, K. Tsuzuki, S. Nakamura, M. Altaf-Ul-Amin, T. Oshima, T. Baba, N. Yamamoto, T. Kawamura, T. Ioka-Nakamichi, M. Kitagawa, M. Tomita, S. Kanaya, C. Wada, and H. Mori. 2006. Large-scale identification of protein-protein interaction of Escherichia coli K-12. Genome Res. 16:686-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett III, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd, D., D. S. Weiss, J. C. Chen, and J. Beckwith. 2000. Towards single-copy gene expression systems making gene cloning physiologically relevant: lambda InCh, a simple Escherichia coli plasmid-chromosome shuttle system. J. Bacteriol. 182:842-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butland, G., J. M. Peregrín-Alvarez, J. Li, W. Yang, X. Yang, V. Canadien, A. Starostine, D. Richards, B. Beattie, N. Krogan, M. Davey, J. Parkinson, J. Greenblatt, and A. Emili. 2005. Interaction network containing conserved and essential protein complexes in Escherichia coli. Nature 433:531-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell, R. E., O. Tour, A. E. Palmer, P. A. Steinbach, G. S. Baird, D. A. Zacharias, and R. Y. Tsien. 2002. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7877-7882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalker, A. F., D. R. Leach, and R. G. Lloyd. 1988. Escherichia coli sbcC mutants permit stable propagation of DNA replicons containing a long palindrome. Gene 71:201-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connelly, J. C., and D. R. Leach. 2002. Tethering on the brink: the evolutionarily conserved Mre11-Rad50 complex. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27:410-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cromie, G. A., C. B. Millar, K. H. Schmidt, and D. R. Leach. 2000. Palindromes as substrates for multiple pathways of recombination in Escherichia coli. Genetics 154:513-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.den Blaauwen, T., M. E. Aarsman, L. J. Wheeler, and N. Nanninga. 2006. Pre-replication assembly of E. coli replisome components. Mol. Microbiol. 62:695-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2002. Signal transduction and regulatory mechanisms involved in control of the σS (RpoS) subunit of RNA polymerase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:373-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khlebnikov, A., K. A. Datsenko, T. Skaug, B. L. Wanner, and J. D. Keasling. 2001. Homogeneous expression of the P(BAD) promoter in Escherichia coli by constitutive expression of the low-affinity high-capacity AraE transporter. Microbiology 147:3241-3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lange, R., and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1991. Identification of a central regulator of stationary-phase gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5:49-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau, I. F., S. R. Filipe, B. Søballe, O.-A. Økstad, F.-X. Barre, and D. J. Sherratt. 2003. Spatial and temporal organization of replicating Escherichia coli chromosomes. Mol. Microbiol. 49:731-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leach, D. R., and F. W. Stahl. 1983. Viability of lambda phages carrying a perfect palindrome in the absence of recombination nucleases. Nature 305:448-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemon, K. P., and A. D. Grossman. 1998. Localization of bacterial DNA polymerase: evidence for a factory model of replication. Science 282:1516-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mascarenhas, J., H. Sanchez, S. Tadesse, D. Kidane, M. Krisnamurthy, J. C. Alonso, and P. L. Graumann. 2006. Bacillus subtilis SbcC protein plays an important role in DNA inter-strand cross-link repair. BMC Mol. Biol. 7:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meile, J. C., L. J. Wu, S. D. Ehrlich, J. Errington, and P. Noirot. 2006. Systematic localisation of proteins fused to the green fluorescent protein in Bacillus subtilis: identification of new proteins at the DNA replication factory. Proteomics 6:2135-2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merlin, C., S. McAteer, and M. Masters. 2002. Tools for characterization of Escherichia coli genes of unknown function. J. Bacteriol. 184:4573-4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller, J. H. 1982. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 20.Molina, F., and K. Skarstad. 2004. Replication fork and SeqA focus distributions in Escherichia coli suggest a replication hyperstructure dependent on nucleotide metabolism. Mol. Microbiol. 52:1597-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naom, I. S., S. J. Morton, D. R. Leach, and R. G. Lloyd. 1989. Molecular organization of sbcC, a gene that affects genetic recombination and the viability of DNA palindromes in Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:8033-8045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pastwa, E., and J. Blasiak. 2003. Non-homologous DNA end joining. Acta Biochim. Pol. 50:891-908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patten, C. L., M. G. Kirchhof, M. R. Schertzberg, R. A. Morton, and H. E. Schellhorn. 2004. Microarray analysis of RpoS-mediated gene expression in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Genet. Genomics 272:580-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 25.Slupska, M. M., J. H. Chiang, W. M. Luther, J. L. Stewart, L. Amii, A. Conrad, and J. H. Miller. 2000. Genes involved in the determination of the rate of inversions at short inverted repeats. Genes Cells 5:425-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Typas, A., and R. Hengge. 2005. Differential ability of sigma(s) and sigma70 of Escherichia coli to utilize promoters containing half or full UP-element sites. Mol. Microbiol. 55:250-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Dijl, J. M., A. de Jong, G. Venema, and S. Bron. 1995. Identification of the potential active site of the signal peptidase SipS of Bacillus subtilis. Structural and functional similarities with LexA-like proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 270:3611-3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vijayakumar, S. R. V., M. G. Kirchhof, C. L. Patten, and H. E. Schellhorn. 2004. RpoS-regulated genes of Escherichia coli identified by random lacZ fusion mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 186:8499-8507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weber, H., T. Polen, J. Heuveling, V. F. Wendisch, and R. Hengge. 2005. Genome-wide analysis of the general stress response network in Escherichia coli: σS-dependent genes, promoters, and sigma factor selectivity. J. Bacteriol. 187:1591-1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss, D. S., J. C. Chen, J.-M. Ghigo, D. Boyd, and J. Beckwith. 1999. Localization of FtsI (PBP3) to the septal ring requires its membrane anchor, the Z ring, FtsA, FtsQ, and FtsL. J. Bacteriol. 181:508-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weller, G. R., B. Kysela, R. Roy, L. M. Tonkin, E. Scanlan, M. Della, S. K. Devine, J. P. Day, A. Wilkinson, F. d'Adda di Fagagna, K. M. Devine, R. P. Bowater, P. A. Jeggo, S. P. Jackson, and A. J. Doherty. 2002. Identification of a DNA nonhomologous end-joining complex in bacteria. Science 297:1686-1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]