Abstract

Drug efflux systems contribute to the intrinsic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to many antibiotics and biocides and hamper research focused on the discovery and development of new antimicrobial agents targeted against this important opportunistic pathogen. Using a P. aeruginosa PAO1 derivative bearing deletions of opmH, encoding an outer membrane channel for efflux substrates, and four efflux pumps belonging to the resistance nodulation/cell division class including mexAB-oprM, we identified a small-molecule indole-class compound (CBR-4830) that is inhibitory to growth of this efflux-compromised strain. Genetic studies established MexAB-OprM as the principal pump for CBR-4830 and revealed MreB, a prokaryotic actin homolog, as the proximal cellular target of CBR-4830. Additional studies establish MreB as an essential protein in P. aeruginosa, and efflux-compromised strains treated with CBR-4830 transition to coccoid shape, consistent with MreB inhibition or depletion. Resistance genetics further suggest that CBR-4830 interacts with the putative ATP-binding pocket in MreB and demonstrate significant cross-resistance with A22, a structurally unrelated compound that has been shown to promote rapid dispersion of MreB filaments in vivo. Interestingly, however, ATP-dependent polymerization of purified recombinant P. aeruginosa MreB is blocked in vitro in a dose-dependent manner by CBR-4830 but not by A22. Neither compound exhibits significant inhibitory activity against mutant forms of MreB protein that bear mutations identified in CBR-4830-resistant strains. Finally, employing the strains and reagents prepared and characterized during the course of these studies, we have begun to investigate the ability of analogues of CBR-4830 to inhibit the growth of both efflux-proficient and efflux-compromised P. aeruginosa through specific inhibition of MreB function.

The activity of efflux-based drug extrusion mechanisms impact the overall effectiveness of current antimicrobial therapies and impair efforts to discover new chemotherapeutic treatments for many serious bacterial diseases (4, 42, 43, 65). Few bacterial pathogens exemplify the importance of the interplay between xenobiotic efflux extrusion systems and the exclusion of antimicrobial agents at the level of the poorly permeable gram-negative outer membrane quite like Pseudomonas aeruginosa (46, 58). Indeed, this organism has the capacity to encode more than 50 potential multidrug transporters including 12 resistance nodulation/cell division (RND)-class transporters, which to date, represent the only clinically significant drug transporters that have been experimentally validated for P. aeruginosa (20, 58).

The MexAB-OprM tripartite pump confers basal resistance to P. aeruginosa to a number of chemically distinct antibiotics (58) and through gain-of-function mutations, including those in regulatory proteins (e.g., mexR or mexZ), may overproduce MexAB-OprM or other RND-class pumps which are significant contributors to multidrug resistance in clinical P. areuginosa isolates (41, 71). Four additional RND-class efflux transporters—MexCD-OprJ (54), MexEF-OprN (35), MexGHI-OpmD (44, 69), and MexJK (14)—have been linked to antibiotic resistance in this bacterium, and although some overlap is apparent, the transporters vary with regard to the number and types of substrates recognized for extrusion (reviewed in references 52, 53, 55, and 58). The importance of intrinsic and inducible efflux resistance mechanisms in P. aeruginosa is underscored by the more recent finding that such pumps recognize and transport multiple classes of newly developed antibiotics including tigecycline, a first in the class of glycylcyclines which was developed specifically to circumvent the prevalent tetracycline resistance mechanisms including extrusion by tetracycline-specific efflux pumps (17, 27, 39).

Although much is now known about the contribution of the multidrug efflux (Mex) pumps regarding their importance toward the development of clinical resistance of P. aeruginosa to existing antibiotic therapies, far less is known about the contribution of such pumps to the recognition and extrusion of novel antibacterial agents which are an integral part of the antibacterial discovery and development process. To better understand the potential impact of intrinsic efflux systems in P. aeruginosa in discovery programs directed toward the identification of new antibacterial agents, we constructed a 20-member strain panel of P. aeruginosa derivatives encompassing deletion-replacement mutations of 52 candidate efflux systems including the TolC homolog, OpmH (20). Using this strain panel as a test platform, we undertook a series of studies to identify antimicrobial compounds that specifically inhibit the growth of individual P. aeruginosa strains that are each deficient in one or more multidrug efflux pump systems but not the growth of the wild-type efflux-proficient parent. By definition, compounds identified in this fashion already possess cell-based activity under specific efflux-deficient conditions and thus have a distinct advantage over compounds discovered in target-based biochemical assays that often have properties inconsistent with effective cell penetration. Further, as such compounds lack antimicrobial activity against efflux-proficient strains, they would not be discovered in conventional cell-based screens employing wild-type strains. As such, these novel antimicrobial agents represent unique starting points for chemistry optimization efforts focused initially on overcoming the efflux liability while retaining target-directed activity.

We report herein the identification and characterization of one such compound, CBR-4830, that was discovered through a whole-cell antibacterial screen as a growth inhibitor of efflux-compromised P. aeruginosa strains. We further show through combined genetic, biochemical, and cell morphology studies that the cellular target for CBR-4830 in efflux-compromised P. aeruginosa is MreB, a bacterial homolog of actin. Previous studies of MreB homologs have established that the protein forms dynamic, actin-like helical filaments in an ATP- or GTP-dependent fashion that are localized in the cell on the inner surface of the cytoplasmic membrane (18, 22, 31, 62, 66). Studies undertaken in a variety of rod-shaped, helical, and filamentous bacteria have provided evidence for roles in the maintenance of cell shape (5, 24, 32), polar protein localization (47), and/or chromosome segregation (25, 37, 38).

Additional genetic and microscopy studies described herein establish that the MreB homolog of P. aeruginosa is both essential for cell viability and for maintenance of a rod cell morphology. In light of the prior identification (29, 30) and characterization of the cellular mode of action of a novel S-benzylisothiourea class of MreB inhibitors (21, 25, 32, 47), the potential of MreB as a novel target for antibacterial discovery and development efforts has recently been discussed (67). The identification and characterization of CBR-4830 as a novel indole class of inhibitor of this essential cytoskeleton-like protein represents a first step toward the development of a wholly new class of antipseudomonal agents.

(A portion of this work was presented at the 44th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Washington, DC, 30 October to 2 November 2004.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth media.

Relevant details of the bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Luria-Bertani (LB) or cation-adjusted Mueller Hinton medium was used for routine propagation of P. aeruginosa and Escherichia coli. Genetic manipulations of P. aeruginosa employed citrate-based Vogel-Bonner minimal medium (VBMM) (8). Antibiotic selection concentrations were ampicillin at 100 μg/ml for E. coli, tetracycline at 25 μg/ml and carbenicillin at 200 μg/ml for P. aeruginosa, and gentamicin sulfate at 30 μg/ml and 10 μg/ml for P. aeruginosa and E. coli, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Gene(s) deleted | Source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa strains | |||

| CB046 | PAO1; wild type | PAO1; P. Greenberg laboratory | |

| CB391 | PAO1 Δ(mexAB-oprM)::FRT | PA0425, PA0426, PA0427 | PAO200; 11a |

| CB392 | PAO1 Δ(mexAB-oprM)::FRT Δ(mexCD-oprJ)::FRT | PA0425, PA0426, PA0427, PA4597, PA4598, PA4599 | PAO238; 11a |

| CB393 | PAO1 Δ(mexAB-oprM)::FRT Δ(mexEF-oprN)::FRT | PA0425, PA0426, PA0427, PA2493, PA2494, PA2495 | PAO255; 11a |

| CB394 | PAO1 Δ(mexAB-oprM)::FRT Δ(mexXY)::FRT | PA0425, PA0426, PA0427, PA2018, PA2019 | PAO280; 11a |

| CB398 | PAO1 Δ(mexAB-oprM)::FRT Δ(mexCD-oprJ)::FRT Δ(mexXY)::FRT Δ(mexJKL)::FRT Δ(opmH)::FRT | PA0425, PA0426, PA0427, PA4597, PA4598, PA4599, PA2018, PA2019, PA2020, PA3676, PA3677, PA3678, PA4974 | PAO386; 12 |

| CB602 | CB046 Δ(mexXY)::FRT | PA2018, PA2019 | This study |

| CB536 | CB046 Δ(mexCD-oprJ)::FRT | PA4597, PA4598, PA4599 | This study |

| CB603 | CB046 Δ(mexEF-oprN)::FRT | PA2493, PA2494, PA2495 | This study |

| CB462 | CB046 Δ(mexHI-opmD)::FRT | PA4206, PA4207, PA4208 | This study |

| CB494 | CB046 Δ(mexJK)::FRT | PA3676, PA3677 | This study |

| CB480 | CB046 Δ(opmH)::FRT | PA4974 | This study |

| CM324 | CB398 mreB(I124S) | This study | |

| CM486 | CB398 mreB(I124F) | This study | |

| CM480 | CB398 mreB(P113R) | This study | |

| CM482 | CB398 mreB(P113L) | This study | |

| CM479 | CB398 mreB(D163Y) | This study | |

| CM487 | CB398 mreB(D163G) | This study | |

| CM492 | CB398 mreB(M74V) | This study | |

| CM493 | CB398 mreB(S14L) | This study | |

| CM317 | CB398 pUCP30T | This study | |

| CB831 | CB398 pUCP30T-mexAB-oprM+ | This study | |

| CM318 | CB398 with pUO377 | This study | |

| CM320 | CB398 with pUO270 | This study | |

| CM319 | CB398 with pUO271 | This study | |

| CM358 | CB398 with pCM358 | This study | |

| CB998 | CB398 mreB+attTn7::MCS | This study | |

| CB994 | CB398 mreB+attTn7::mreBWT | This study | |

| CB996 | CB398 mreB+attTn7::mreB(E141G) | This study | |

| CB1034 | CB398 ΔmreB-aacI attTn7::mreBWT | This study | |

| CB1036 | CB398 ΔmreB-aacI attTn7::mreB(E141G) | This study | |

| Plasmids | |||

| pUCP30T | Gmr; broad-host-range cloning vector | 68 | |

| pUCP30T-mexAB-oprM+ | Gmr; pUCP30T expressing mexAB-oprM from Plac | This study | |

| pUO377 | Gmr; pUCP30T containing mreB(E141G) mreCWTgatCWT | This study | |

| pUO270 | Gmr; pUCP30T containing mreB(E141G) mreCWT | This study | |

| pUO271 | Gmr; pUCP30T expressing mreB(E141G) | This study | |

| pCM358 | Gmr; pUCP30T expressing mreBWT | This study | |

| pUC18R6K-mini-Tn7T-Gm | Gmr; mini-Tn7 for gene insertion at glmS attTn7 | 8 | |

| pCM370 | Gmr; mini-Tn7T-Gm with mreBWT | This study | |

| pCM372 | Gmr; mini-Tn7T-Gm with mreB(E141G) | This study | |

| pTNS1 | Apr; helper plasmid with TnsABCD transposase | 8 | |

| pBAD/HisB | Apr; cloning vector for N-terminal His6-tagged proteins | Invitrogen | |

| pBad/HisB-MreBWT | Apr; pBAD/HisB expressing His6-mreBWT | This study | |

| pBad/HisB-MreB(P113R) | Apr; pBAD/HisB expressing His6-mreB(P113R) | This study | |

| pBad/HisB-MreB(E141G) | Apr; pBAD/HisB expressing His6-mreB(E141G) | This study |

Abbreviations: Gmr, gentamicin resistance; Apr, ampicillin resistance; Plac, E. coli lac operon promoter; MCS, multiple cloning site.

Whole-cell screening and antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Initial assessment of inhibitory activity was determined by growth inhibition of P. aeruginosa CB398 cultivated at a density of ∼5 × 105 CFU/ml in 0.1 ml of LB in a 384-well plate format. Individual compounds prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were dosed at a final screening concentration of 5 μM. Growth or inhibition was measured by absorbance at 630 nm using a Wallac Envision 2100 multilabel plate reader (Perkin Elmer). Experimental compounds that inhibited growth (>50%) compared to the untreated growth control containing only DMSO were selected for further analysis. Rifampin and chloramphenicol were included as positive controls. MICs were determined by the broth microdilution method using twofold serial dilutions of compound in cation-adjusted Mueller Hinton broth (15).

Resistance genetics and mutant isolation.

P. aeruginosa CB398 was cultured in LB medium to early stationary phase, and the cell suspension was concentrated to ∼1011 CFU/ml following recovery of cells by centrifugation. Aliquots containing 109 to 1010 CFU were then plated on LB agar supplemented with either CBR-4830 or rifampin at twofold doubling dilutions (16 to 128 μM). Spontaneously resistant colonies were counted after incubation for 1 to 3 days at 35°C and used to calculate the apparent drug resistance frequency for each agent. A subset of resistant clones was purified through drug-free passage, and single-colony isolates were subsequently tested for changes in antibiotic resistance by broth microdilution assay.

Identification of the CBR-4830-resistant determinant.

Genomic DNA was isolated from pooled CBR-4830-resistant variants of P. aeruginosa CB398 using a Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI.). Purified genomic DNA was partially digested with Sau3A1, fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and ligated into pUCP30T (68) following sequential treatment of the vector with BamHI and shrimp alkaline phosphatase. The resultant recombinant plasmid DNA library was introduced into CB398 by electroporation (13), and clones that conferred stable heritable resistance to CBR-4830 were identified following coselection for the vector-encoded resistance (i.e., gentamicin) and CBR-4830 resistance at 32 μM. Plasmid pUO377 (Table 1; see also text below) was identified in this manner following two subsequent rounds of passage through a naïve CB398 host and coselection for gentamicin and CBR-4830 resistance as above. Restriction mapping and in vitro random mutagenesis with EZ::TN <TET-1> (Epicenter Biotechnologies, Madison, WI) were employed to localize the CBR-4830-resistant determinant of pUO377. For PCR analysis of mreB or mreBC variants from CBR-4830-resistant or -sensitive clones, plasmid or genomic DNA was used as a template for gene amplification using Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) in a standard reaction mixture further supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) DMSO and 1 M betaine (pH 9), which improves the amplification efficiency of high-GC-content templates. To aid in directional cloning, PCR primers were engineered to carry terminal KpnI and HinDIII restriction sties.

Recombinant DNA methods for P. aeruginosa.

Construction of PAO1 derivatives deficient in one or more efflux pump systems was accomplished using a targeted deletion-replacement mutagenesis approach involving SacB-mediated sucrose counter-selection and Flp recombinase (28). Recombinant mexA-mexB-oprM operon was amplified from the PAO1 genome with the following primer pair: 5′-GATCGAGCTCATGCAACGAACGCCAGCCATGCGTGTACTG-3′ and 5′-GATCTCTAGATCAAGCCTGGGGATCTTCCTTCTTCGCGGT-3′ (restriction sites are underlined). Following restriction digestion with SacI and XbaI, the PCR product was directionally cloned into the corresponding sites of pUCP30T to facilitate expression from the vector encoded Plac promoter (59).

P. aeruginosa was engineered to ectopically express alleles of mreB encoding either wild-type protein (MreBWT) or a derivative carrying the mutation E141G [MreB(E141G)] from the distal glmS attTn7 site in the genome of CB398 using a previously described site-specific broad-host-range integration system (8). Briefly, mreBWT or mreB(E141G) alleles with native promoter elements were amplified from CB398 or pUO377, respectively, using the primer pair 5′-CGGGGTACCTCCAGCAAAAGCGGCCTTGGAAGG-3′ and5′-CCCAAGCTTTTACTCGGTGGAGAGCAGGTCCA-3′ (restriction sites are underlined). Purified PCR products were treated with KpnI and HinDIII and then cloned into a similarly restricted mini-Tn7T-Gm construct. Resultant recombinant plasmids or the parent vector alone were transferred by electroporation along with the pTNS1 helper plasmid into CB398. Electrotransformants were selected on VBMM supplemented with gentamicin, followed by subsequent excision of the gentamicin resistance marker using Flp recombinase (7). A nonpolar mreB gene inactivation cassette in which the coding sequence for the native mreB was replaced from start codon to stop codon with the coding sequence for the aacI gentamicin resistance cassette was cloned into pEX18Ap containing sacB and bla genes and introduced into recombinant P. aeruginosa by conjugation. Transconjugates were selected on VBMM with gentamicin and were transferred after one round of passage onto VBMM supplemented with 5% sucrose to select for recombination and loss of the vector. Strains carrying null mutations of the native mreB were identified phenotypically as exhibiting resistance to sucrose and gentamicin and sensitivity to carbenicillin. A subset of purified clones was subsequently confirmed by diagnostic PCR analysis of the native mreB locus and the recombinant mini-Tn7 element integrated at the glmS attTn7 site.

Phase-contrast microscopy.

Cultures of P. aeruginosa were grown in LB broth with aeration to early to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm of 0.2 to 0.5) and were then split into multiple tubes and exposed to DMSO control or test compounds at the indicated concentration (see Table 3) for up to 180 min at 37°C with agitation. Portions of the cell suspension were examined immediately by phase-contrast microscopy and also preserved in 10% buffered neutral formalin (3.7% [vol/vol], formaldehyde, 145 mM NaCl, 30 mM KH2PO4, 45 mM Na2HPO4) for longer storage at 4°C. Formalin-fixed cells were immobilized for microscopy by placing a thin pad of 1% (wt/vol) agarose on a microscope slide prior to the addition of the preserved cells.

TABLE 3.

Summary of the structure-activity relationship studies of CBR-4830, related commercial analogs, and control agents

| Compound | MIC (μM) for the indicated straina

|

IC50 in MreB assay (μM)b | CB398 shape (concn [μM])c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB046 | CB398 | CM324 | |||

| CBR-4830 | >64 | 2 | 64 | 46 | Coccoid (32) |

| C7-1007 | >64 | 16 | >64 | 43 | Coccoid (32) |

| C7-0974 | >64 | 16 | >64 | ND | Coccoid (32) |

| C7-1008 | >64 | 8-16 | 16 | >196 | Rod (8)d |

| C7-1009 | >64 | 16 | 16 | >196 | Rod (32) |

| C7-0975 | >64 | 16 | 16 | ND | Rod (8-32) |

| C7-1010 | >64 | >64 | ND | ND | ND |

| A22 | >64 | 4 | >64 | >196 | Coccoid (32) |

| Amdinocillin | >64 | 16 | 16 | >196 | Coccoid (16) |

| Merrem (meropenem) | 4 | 2 | 2 | ND | Filament (0.7-2) |

CB046, efflux-competent mreBWT strain; CB398, efflux-defective mreBWT strain; CM324, efflux-defective mreB(I124S) strain. ND, not determined.

Inhibition of polymerization of wild-type Pseudomonas MreB in light-scattering assays.

Cell shape determined by phase microscopy after 180-min exposure to the indicated agent at the specified concentration.

Cell lysis occurred at higher drug concentrations.

Overexpression and purification of wild-type and mutant MreB proteins.

mreBWT and mutant variants of the P. aeruginosa mreB coding region [mreB(P113R) or mreB(E141G)] were amplified under high-fidelity conditions from strains CB046 (PAO1), CM480, and pUO377, respectively, using Platinum Taq High Fidelity polymerase and the oligonucleotide primer pair 5′-CGGGGTACCATGTTCAAAAAATTGCGTGGCATG-3′ and 5′-CCCAAGCTTTTACTCGGTGGAGAGCAGGTCCA-3′ (restriction sites are underlined). The resultant products were treated with KpnI and HindIII and ligated to similarly treated pBAD/HisB vector (Invitrogen), resulting in recombinant plasmids in which the MreB coding sequence was fused to an amino terminal polyhistidine sequence under transcriptional control of the vector-borne PBAD promoter. For expression of wild-type or mutant MreB forms, E. coli TOP10 (Invitrogen) transformed with the plasmid pBAD/HisB-MreBWT, pBAD/HisB-MreB(E141G) or pBAD/HisB-MreB(P113R) were grown at 37°C with agitation to exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.6) in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin. Expression was induced by the addition of l-arabinose to a final concentration of 0.2% (wt/vol), and incubation was continued for 5 h. Cell pellets were recovered by low-speed centrifugation and processed in lysis buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol) supplemented with 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM MgCl2, a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Complete, EDTA free; Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN), and DNase I by sequential treatment with lysozyme and sonication. The resultant cleared lysate was bound to Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose resin (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA) and washed with lysis buffer containing 20 mM imidazole, and the recombinant N-His6-MreB proteins were eluted with a buffer of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, and 250 mM imidazole. The resulting eluate was then dialyzed against storage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and 50% glycerol). Following dialysis, the protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay, and samples were aliquoted and stored at −70°C.

In vitro assays of MreB polymerization.

MreB polymerization was measured by 90°-angle light scattering in a Hitachi F-4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer with both the excitation and emission wavelengths set at 310 nm and a slit width of 1 nm (45). At the indicated times (see Fig. 6), MreB (9.4 μM), the tested compound or DMSO, and ATP were added to the sample cuvette. In all cases, the final concentrations of the components of the buffer were 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 8 mM MgCl2, and 17.6 mM ATP. Data were continuously collected for a specified period of time. The shutter was closed during the time required to add MreB, compound or DMSO, and ATP, which caused the light-scattering signal to briefly fall to zero. A second, filtration-based assay for ATP-dependent MreB polymerization was undertaken using a purified recombinant form of the Thermotoga maritima MreB1 (TM0588) protein (66). In these studies, MreB1 was employed at 1 mg/ml in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, and 5 mM ATP in reaction mixtures containing 5% (vol:vol) DMSO or test compound. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and the polymerized MreB1 forms were separated by retention on Ultrafree-MC 0.22-μm-pore-size Durapore Centrifugal Filter Units (Amicon UFC3 0GV 00). Briefly, the Ultrafree-MC units were prewashed by adding 0.4 ml of 0.1% bovine serum albumin and centrifuged for 1 min at 12,000 × g at 25°C; the wash step was repeated twice with reaction buffer. Reaction mixtures were applied to the column in 40-μl volumes and centrifuged for 1 min at 12,000 × g at 25°C. The flowthrough fraction was collected as the unpolymerized or soluble fraction and combined with an equal volume of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer and stored on ice. The filters were then washed twice with 0.4 ml of reaction buffer, and the polymerized forms retained on the filter were recovered in a quantitative fashion by adding 80 μl of 1× SDS-PAGE sample buffer and heating the spin columns at 99°C for 15 min. For electrophoretic gel analysis, equivalent volumes of the soluble and polymerized samples from each reaction set were loaded in adjacent lanes of an SDS-PAGE gel. Finally, T. maritima MreB1 structures formed in vitro that were examined by electron microscopy were prepared as described above for the filtration assay except that 3 mM CaCl2 was added to the assay buffer as described previously (66).

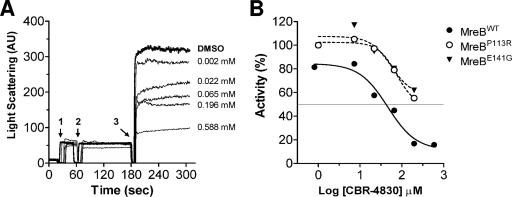

FIG. 6.

Light-scattering assay for MreB in vitro polymerization. (A) Light scattering caused by ATP-dependent MreB polymerization was measured at an angle of 90° from the direction of incident light in the absence (DMSO) or presence of indicated concentrations of CBR-4830. The numbered arrows indicate when MreB protein was added (1), when CBR-4830 or DMSO was added (2), and when ATP was added to the cuvette (3). (B) Inhibition curves for wild-type or CBR-4830-resistant MreB in light-scattering assays. Percent activity is defined as the remaining activity of the drug-treated sample over that of the untreated control, multiplied by 100 [(activity of drug-treated sample/activity of untreated sample) × 100].

RESULTS

Identification of CBR-4830 through whole-cell antibacterial screening of an efflux-compromised PAO1 strain.

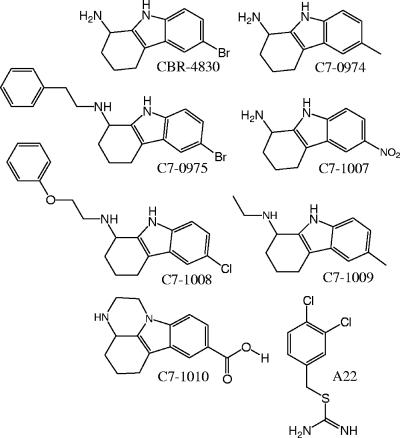

In a previous study, we reported the construction and characterization of a 20-member panel of derivatives of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain that each bore deletions in multiple putative efflux systems (20). In a discovery program focused on the identification of novel antipseudomonal agents, we deployed a strain panel of efflux-defective mutants including a P. aeruginosa PAO1 derivative (CB398) bearing deletion-replacements of four RND-class efflux systems (mexAB-oprM, mexCD-oprJ, mexXY, and mexJKL) and also opmH (TolC) in a high-throughput screen of a library of diverse synthetic compounds. Following a confirmation step in which the activity of each identified compound was confirmed through a second independent growth inhibition assay, a number of “hits” were identified that represent compounds that inhibited the growth of efflux-defective mutant strains, but not the wild-type parent, at a concentration of 5 μM. Of these, an indole-class compound (CBR-4830) (Fig. 1) was identified as a compound active against CB398 (96 to 99% growth inhibition at 5 μM).

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of CBR-4830, CBR-4830-related compounds, and the structurally unrelated A22 compound as employed in this study.

Antibacterial activity of CBR-4830 is compromised by MexAB-OprM in PAO1.

Since CBR-4830 was identified using a strain deficient in numerous efflux pumps, we determined whether the antibacterial activity of this compound was impaired by a single pump or if multiple pumps contributed to the extrusion of this compound. In broth microdilution MIC assays, the antimicrobial activity of CBR-4830 was significantly improved in strains lacking mexAB-oprM (32- to 128-fold) and to a lesser extent in strain CB602 lacking mexXY (4-fold) (Table 2). Inactivation of other transporters including mexCD-oprJ, mexEF-oprN, mexJK, or opmH alone had no apparent effect on the MIC of CBR-4830. Consistent with previous reports in the literature (12, 58), antimicrobial activity of rifampin was unaffected by mutation of the four major RND-class transporters in P. aeruginosa PAO1. In contrast, differential sensitivity for the tested strains was observed for chloramphenicol (primarily a substrate for MexAB-OprM) and triclosan (a substrate for multiple RND-class transporters). Taken as a whole, these data are interpreted to indicate that MexAB-OprM is the principal pump involved in extrusion of CBR-4830 from P. aeruginosa PAO1.

TABLE 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of efflux-compromised P. aeruginosa

| Strain | Relevant description | MIC of the indicated drug (μM)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBR-4830 | CAM | TRI | RIF | ||

| CB046 | Wild-type parent (PAO1) | 128 | >128 | >128 | 8 |

| CB398 | Δ(mexAB-oprM) Δ(mexCD-oprJ) Δ(mexXY) Δ(mexJKL) Δ(opmH) | 1 | 2 | 8 | 16 |

| CM318 | CB398 × pUCP30T-mreB(E141G) mreC gatC | 32 | NT | NT | NT |

| CM319 | CB398 × pUCP30T-mreB(E141G) | 32 | NT | NT | NT |

| CM358 | CB398 × pUCP30T-mreBWT | 2 | NT | NT | NT |

| CB391 | Δ(mexAB-oprM) | 2 | 4 | 64 | 16 |

| CB392 | Δ(mexAB-oprM) Δ(mexCD-oprJ) | 1 | 4 | 32 | 16 |

| CB393 | Δ(mexAB-oprM) Δ(mexEF-oprN) | 4 | 4 | 64 | 8 |

| CB394 | Δ(mexAB-oprM) Δ(mexXY) | 4 | 4 | 64 | 8 |

| CB602 | Δ(mexXY) | 32 | >128 | >128 | 8 |

| CB536 | Δ(mexCD-oprJ) | 128 | >128 | >128 | 8 |

| CB603 | Δ(mexEF-oprN) | 128 | >128 | >128 | 16 |

| CB462 | Δ(mexHI-opmD) | 128 | >128 | >128 | 16 |

| CB494 | Δ(mexJK) | 128 | >128 | >128 | 8 |

| CB480 | Δ(opmH) | 128 | >128 | >128 | 8 |

| CB831 | CB398 × pUCP30T-mexAB-oprM | 32 | 64 | >128 | 16 |

TRI, triclosan; CAM, chloramphenicol; RIF, rifampin; NT, not tested.

In order to confirm the requirement for MexAB-OprM in the extrusion of CBR-4830 from P. aeruginosa, we cloned and then expressed recombinant mexAB-oprM from an extrachromosomal multicopy plasmid in the CB398 strain background. Expression of MexAB-OprM in these studies was observed to restore resistance of CB398 to triclosan, chloramphenicol, and CBR-4830 to near wild-type levels, thus providing genetic evidence that inactivation of mexAB-oprM is both necessary and sufficient to confer the reduced sensitivity of CB398 to CBR-4830 (Table 2).

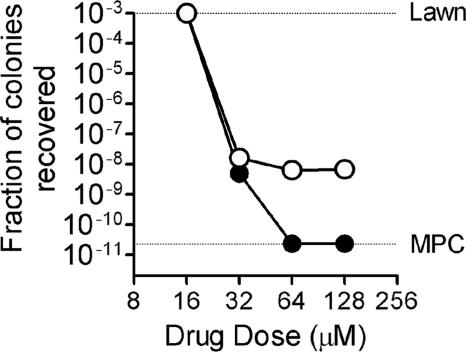

Generation and characterization of CBR-4830-resistant mutants.

Derivatives of P. aeruginosa CB398 that exhibit CBR-4830 resistance arose in vitro on agar medium supplemented with 32 μM CBR-4830 at a frequency of ∼5 × 10−9, similar to that observed for rifampin (Fig. 2). Resistant mutants were not similarly recovered at higher CBR-4830 drug concentrations, possibly indicating that the in vitro mutant prevention concentration (19) of this agent is achieved at these drug concentrations. Sixteen putative CBR-4830-resistant derivatives of CB398 were purified through a drug-free passage and then evaluated for changes in susceptibility to CBR-4830 and control agents by broth microdilution MIC assays. Fifteen of 16 purified CBR-4830 selectants showed elevated resistance to CBR-4830 (see Fig. 4), but all remained equivalently sensitive to other known efflux substrates including triclosan and trimethoprim (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

The effect of increasing drug concentration on the recovery of single-step resistant mutants. P. aeruginosa CB398 was grown to stationary phase, and aliquots of concentrated cell suspensions were spread on agar plates containing increasing concentrations of CBR-4830 (filled circles) or rifampin (open circles). Following incubation at 37°C, colonies were enumerated, and the fraction recovered relative to the input number of CFU per plate was determined for the specific drug concentration. Lawn refers to the point at which individual colonies could no longer be distinguished. The mutant prevention concentration (MPC) corresponds to the minimal drug concentration in plates which suppressed the growth of any resistant colonies.

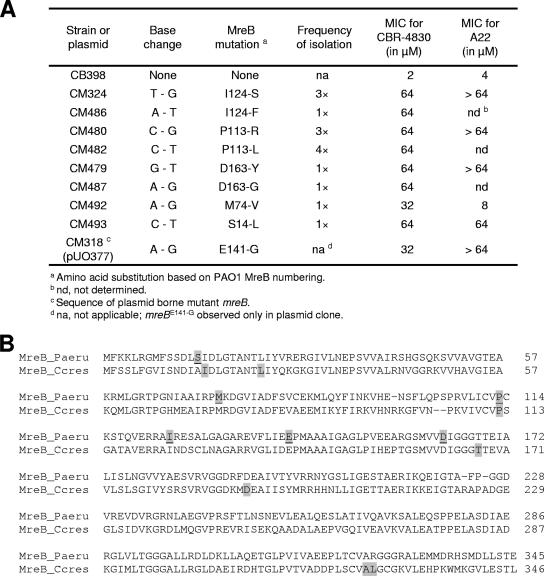

FIG. 4.

CBR-4830 resistance mutations map to chromosomal mreB in the efflux-compromised P. aeruginosa CB398 strain. (A) Sequence analysis of mreB from 15 CBR-4830-resistant CB398 selectants and the original complementing plasmid revealed the presence of nine discrete missense mutations resulting in the indicated amino acid substitution in MreB. Numbering is based on the PAO1 MreB peptide sequence. The resulting change in susceptibility of CB398 to CBR-4830 or A22 in MIC assays is given. (B) Alignment of the P. aeruginosa MreB (MreB_Paeru) and the C. crescentus MreB (MreB_Ccres) proteins. The residues that were mutated in the 15 CBR-4830-resistant Pseudomonas CB398-selectants are highlighted (shaded and underlined) and compared to the 20 MreB mutations reported (25) for A22-resistant C. crescentus strains (shaded).

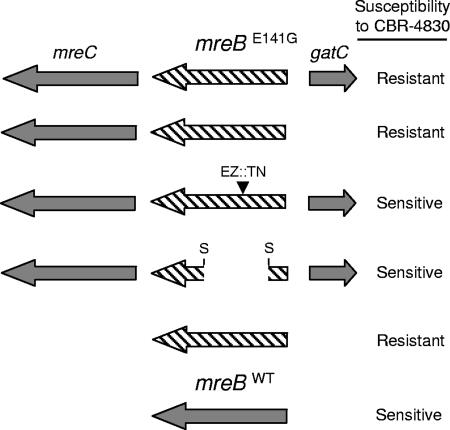

To delineate the mechanism(s) underlying the observed CBR-4830 resistance and therein possibly elucidate the mode of action of this class of compound, a random plasmid-based genomic library was generated from DNA recovered from the original pool of CBR-4830-resistant mutants and was subsequently used to transform CB398 to elevated resistance to CBR-4830. A single recombinant plasmid clone, referred to hereafter as pUO377 (Table 1), was subsequently identified as being capable of transferring stable, heritable CBR-4830 resistance and was shown by plasmid mapping and DNA sequence analysis to carry three full-length open reading frames (ORFs)—PA4480, PA4481, and PA4482—annotated in the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome as mreC, mreB, and gatC, respectively (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Plasmid-based genetic screen to map CBR-4830 resistance to mreB in efflux-compromised P. aeruginosa CB398. Plasmid pUO377 that confers heritable resistance to CBR-4830 contains three full-length ORFs corresponding to mreC (PA4480), mreB (PA4481), and gatC (PA4482). Arrows indicate the predicted direction of transcription of each. The mutant form of mreB is depicted graphically as a hatched arrow. Dark gray arrows indicate that the nucleotide sequence of the gene was wild type. Sequence analysis of the genomic DNA insert in pUO377 revealed a single-nucleotide polymorphism in mreB resulting in an mreB(E141G) missense mutation. Inactivation of the mutant mreB(E141G) ORF by removal of an internal 0.48-kb SmaI fragment (S) or random insertion of EZ::TN <TET-1> in mreB(E141G) was sufficient to cause reversion of an efflux-compromised CB398 host to CBR-4830 sensitivity in MIC assays. Expression of mreB(E141G) but not mreBWT alone from pUCP30T was sufficient to confer heritable resistance to CBR-4830 to a naive efflux-compromised CB398 host.

Mutated MreB is necessary and sufficient to confer resistance of efflux-compromised P. aeruginosa strains to CBR-4830.

Sequence analysis of the entire insert cloned in pUO377 identified a single-nucleotide polymorphism (with respect to the parental P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome sequence) in the ORF of the mreB gene corresponding to an MreB(E141G) missense mutation. The relevance of this mutation was confirmed in a follow-up study wherein it was observed that the mutant form of mreB [MreB(E141G)] expressed alone from pUCP30T, but not a similarly cloned wild-type copy of mreB (MreBWT), was sufficient for genetic transfer of CBR-4830 resistance to a naïve CB398 host. Furthermore, disruption of the plasmid-borne mreB(E141G) ORF by standard recombination methods or by in vitro random transposon mutagenesis using the EZ::TN <Tet-1> element resulted in reversion to CBR-4830 sensitivity (Fig. 3).

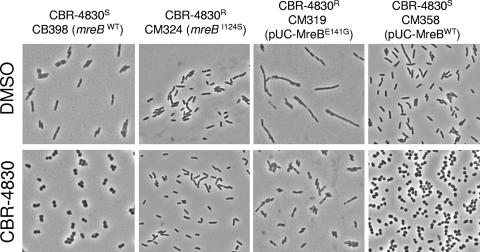

To verify that the original CBR-4830 selection resulted in the selection of strains bearing spontaneous missense mutations in mreB, we also determined the nucleotide sequence of mreB from the 15 purified stable CBR-4830-resistant CB398 derivatives, as well as the CBR-4830-sensitive parent strain CB398. All 15 purified CBR-4830-resistant variants carried individual nucleotide polymorphisms resulting in several discrete missense mutations in mreB, while no such mutations were observed in the CBR-4830-sensitive CB398 parent strain (Fig. 4A and B). Systematic evaluation of the growth properties of the CB398 derivatives bearing missense mutations in mreB was not undertaken; however, these recovered mutants appear to retain normal growth properties in standard laboratory medium and, where evaluated (Fig. 5), appear to maintain normal cell morphology in both the presence and absence of CBR-4830. This result is consistent with the minimal impact such mutations were found to have on cell growth of an unrelated organism, Caulobacter crescentus, bearing missense mutations in mreB (25).

FIG. 5.

Effects of CBR-4830 on the cell morphology of efflux-compromised P. aeruginosa strains. Efflux-compromised P. aeruginosa strains bearing wild-type or CBR-4830-resistant mreB alleles either at the native chromosomal location or expressed in trans from an extrachromosomal plasmid were exposed to 32 μM CBR-4830 for 180 min and examined by phase-contrast microscopy.

To confirm the apparent role of mutant mreB alleles in conferring resistance to CBR-4830, we employed a previously described site-specific mini-Tn7 vector system (6, 8) to construct merodiploid CB398 derivatives that expressed either the wild-type mreB (MreBWT) or mutant mreB [MreB(E141G)] in single-copy form under control of the native promoter elements at the distal glmS attTn7 locus. A control strain in which the empty multicloning site from mini-Tn7T-Gm vector (6) was integrated at the attTn7 site was also constructed (Table 1). Using a nonpolar, site-specific gene replacement strategy so as to minimize potential polar effects on native downstream mreC (PA4480) and mreD (PA4479), we readily recovered deletion-replacement mutants of native mreB in CB398 derivatives that also expressed MreBWT or MreB(E141G) ectopically from the attTn7 site. However, we failed to resolve intermediate integrants in a strain that lacked a second functional copy of mreB (data not shown). This result is wholly consistent with the idea that MreB performs an essential cellular function in P. aeruginosa PAO1, as has been reported for other bacterial species (24, 31, 38). Subsequent MIC studies using the recovered recombinant merodiploid strains that expressed only mreBWT or mreB(E141G) from attTn7 confirmed the role of the mutant mreB(E141G) in elevated resistance of CB398 to CBR-4830 (data not shown). As a whole, these results are highly suggestive that the mreB gene product performs an essential function in P. aeruginosa PAO1 and serves as the direct cellular target of CBR-4830.

CBR-4830 treatment confers morphological changes that are characteristic of MreB depletion.

MreB is a prokaryotic actin homolog that has been shown to be essential for cell viability, cell shape, polar protein localization, and chromosome segregation in a wide array of bacterial species (5, 67). Central to the role of MreB in these processes is its ability to directionally polymerize (assemble) into dynamic spherical filaments in the bacterial cell (66). Owing to the mechanical functions of MreB in determining the rod shape, a characteristic feature of multiple bacteria when they are depleted of MreB by either molecular genetic approaches or following treatment with chemical agents such as S-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl)isothiourea (A22) is the tendency to lose the rod shape and transition to spherical cells (25, 30, 47). To determine the effects of CBR-4830 treatment on cell shape in P. aeruginosa, we exposed actively growing cultures of CB398 (efflux-compromised, MreBWT and CBR-4830 susceptible) or CM324 [efflux-compromised, MreB(I124S) and CBR-4830 resistant] to CBR-4830 at a concentration of 32 μM for 180 min and then examined portions of the resulting cell suspensions using phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 5). As expected, treatment of CBR-4830-sensitive, rod-shaped CB398 with CBR-4830 results in cell rounding that is characteristic of MreB-depleted cells (47). In contrast, treatment of the CBR-4830-resistant CM324 strain, bearing a mutant mreB(I124S) allele, did not result in loss of the rod shape. These data are wholly consistent with a model wherein CBR-4830 directly impairs MreB function and with the notion that specific point mutations in mreB both confer resistance to CBR-4830 and protect the cell from gross morphological changes that might be anticipated from MreB depletion. Untreated cells of the CBR-4830-resistant strain CM319, which has a wild-type native mreBWT and also expresses mutant mreB(E141G) from pUO271, are significantly elongated but revert to apparently normal rod-shaped morphology upon CBR-4830 exposure (Fig. 5). As this behavior is distinct from that observed for a CBR-4830-sensitive control strain bearing either the base vector alone (not shown) or expressing mreBWT in trans (Fig. 5, CM358), this is interpreted to mean that overexpression of the mreB(E141G) mutant protein in some way impairs normal cell growth and/or cell division, possibly by competing directly with native MreBWT function.

Assessment of CBR-4830 mode of action through an in vitro light-scattering assay of MreB polymerization.

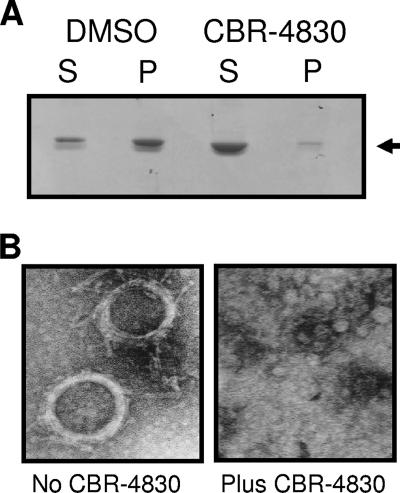

In an effort to further delineate the mode of action of CBR-4830 as a modulator of MreB function, recombinant forms of wild-type MreB plus two mutant forms derived from CBR-4830-resistant variants [mreB(E141G) and mreB(P113R)] were cloned into the pBAD/HisB vector, overexpressed, and purified to near homogeneity from a recombinant E. coli host (data not shown). Using a previously described assay for in vitro MreB protein polymerization (22), we observed rapid ATP-dependent changes in light scatter intensity for purified recombinant MreB (Fig. 6A), which is indicative of the in vitro conversion of MreB monomers into polymerized MreB protofilaments. Addition of CBR-4830 to the test reaction mixture significantly inhibited light scattering of MreBWT in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 6A and B). In contrast, CBR-4830 showed a comparatively marked reduction in its ability to inhibit light scattering of the MreB(E141G) or MreB(P113R) variant when tested under the same assay conditions (Fig. 6B). Equivalent results were obtained using a purified recombinant form of the T. maritima MreB1 (TM0588) protein (66) in an in vitro filtration-based assay of MreB polymerization (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Fig. 7, CBR-4830 treatment of MreB1 significantly decreased the amount of apparent polymerized forms of the protein that are retained by the 0.22-μm-pore-size filter unit. To confirm the polymeric nature of the filter retentate, equivalent reaction mixtures were also examined by electron microscopy methods; these revealed helical forms as spiral superstructures of MreB1 that are reminiscent of previous electron microscopy images of MreB1 filaments (66) but were not observed in samples exposed to CBR-4830 (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

MreB filtration assay (A) and electron micrographs (B) of T. maritima MreB1 structures formed during in vitro polymerization assays at 37°C for 30 min. Soluble (S) and polymerized (P) forms of MreB1 were separated by ultrafiltration and visualized by SDS-PAGE analysis (see Materials and Methods). Electron micrographs (magnification, ×118,000) of MreB1 structures are shown when formed either in the absence or presence of CBR-4830 at 0.1 mM.

Equivalent electron micrographs were not successfully obtained in studies of the P. aeruginosa MreB protein (not shown). Taken as a whole, these data are consistent with a model wherein MreB serves as a direct cellular target for CBR-4830, and specific target-based genetic resistance to this compound arises in P. aeruginosa through mutations in mreB that may affect binding of CBR-4830 to this cellular target (see Discussion).

Inhibition of P. aeruginosa growth and MreB function by CBR-4830 and related compounds.

To begin to assess the chemical specificity of CBR-4830 as an inhibitor of P. aeruginosa MreB function, six commercially available chemical analogs were obtained (Princeton Biomedical) that share the core indole scaffold of CBR-4830 (Fig. 1), and these were tested for antimicrobial potency and cross-resistance in microdilution MIC assays versus the efflux-defective CBR-4830-sensitive CB398 (mreBWT) or CBR-4830-resistant CM324 [mreB(I124S)] strains or the efflux-competent parent strain CB046 (Table 3). Compound A22, a previously characterized modulator of MreB function (25, 29, 47) (Fig. 1), amdinocillin (mecillinam, a PBP2 inhibitor), and meropenem (a PBP2/3 inhibitor) were included as controls. Of the six CBR-4830 analogs tested, only five exhibited appreciable antimicrobial activity versus the efflux-compromised CB398 strain while none showed significant antimicrobial activity versus the efflux-proficient parent strain (CB046). This latter result suggests that all of these compounds are still recognized and excluded by one or more of the four RND-class transporters inactivated in CB398. Two compounds, C7-1007 and C7-0974, were both found to exhibit significant cross-resistance to the CBR-4830-resistant mreB(I124S) allele of strain CM324, whereas MICs of compounds C7-1008, C7-1009, and C7-0975 were unaffected by this resistance mutation. Compound C7-1007 was further observed to transform CB398 to coccoid forms at 32 μM or 2× MIC and also exhibited appreciable activity in inhibiting MreB polymerization in vitro in the light-scattering assay with a calculated 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) equivalent to that of CBR-4830. These data are consistent with the observation that C7-1007 exhibits its antimicrobial effect via cellular perturbation of MreB function. In contrast, neither C7-1008 nor C7-1009 was active in the MreB polymerization assay (i.e., IC50 of >196 μM) and had no discernible effects on the morphology of treated CB398 cells, suggesting that these compounds that are more distantly related to CBR-4830 exhibit antimicrobial activity via a mechanism(s) unrelated to inhibition of MreB function (Table 3). As expected, A22 and amdinocillin induced a coccoid cell morphology, whereas low doses of meropenem promoted cell filamentation. Taken as a whole, these data indicate that CBR-4830, and some closely related analogs (i.e., C7-0974 and C7-1007), inhibit the growth of P. aeruginosa through the specific inhibition of MreB function. This activity is antagonized principally by MexAB-OprM-mediated efflux exclusion and through specific, acquired target-based mutations that arise in the mreB target gene.

As MreB is well conserved and thought to be essential in multiple rod-shaped, filamentous, and helical bacteria (5, 67), we determined whether CBR-4830 exhibits antimicrobial activity and affects the cellular morphology of an E. coli derivative that lacks TolC, an outer membrane channel that plays a key role in intrinsic activity of RND efflux pumps in this organism. At 0.032 mM (equivalent to the MIC for this organism), an E. coli tolC strain was observed to transition from rod shape into spherical cells (data not shown), suggesting that CBR-4830 may target MreB in this organism as well. Further studies would be necessary to unequivocally prove that CBR-4830 inhibits growth of E. coli tolC mutants through specific inhibition of MreB filamentation and to confirm which intrinsic (or inducible) efflux system(s) limits the antimicrobial potency of CBR-4830 against this bacterium. However, this finding raises the possibility that CBR-4830 may have broader utility as both a novel class of antibacterial agent and as an important new experimental tool for the study of the prokaryotic MreB actin-like cytoskeletal network.

DISCUSSION

Despite the promise that combined efforts in bacterial genomics, combinatorial chemistry, and target-based high-throughput screening would deliver new classes of antibacterial agents, no new agents based on these efforts have been introduced into the clinic (16, 56). To inhibit bacterial growth, a compound that is active in vitro must also be able to penetrate the bacterial cell surface, avoid extrusion by a range of efflux mechanisms, and avoid inactivation through modification by host enzymes. P. aeruginosa displays a high level of intrinsic resistance to a variety of structurally unrelated antimicrobial agents due to the interplay of both the low-permeability outer membrane and broad-specificity drug efflux systems (46, 51, 52, 58). Indeed, many otherwise viable and potent antibiotics (e.g., levofloxacin) are rendered ineffective against the pathogen based on the activity of one or more efflux systems alone (36).

In an antibacterial discovery program directed toward the identification of novel antipseudomonal agents, we undertook cell-based screens of a synthetic compound collection using an engineered panel of efflux-defective bacteria including efflux-compromised derivatives of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain (20). The potential of this approach for the identification of novel leads for chemical optimization is exemplified herein through the identification and characterization of CBR-4830, a novel indole-class compound that would not have been identified in a cell-based screen employing wild-type, efflux-proficient strains. The identification of MreB as the proximal cellular target of CBR-4830 (and related compounds C7-1007 and C7-0974) is suggested by the observation that missense mutations in mreB are sufficient to render efflux-sensitized PAO1-derivatives insensitive to CBR-4830. Further, ectopic expression of the mutant mreB(E141G) alone from a distal glmS attTn7 site was sufficient to confer CBR-4830 resistance to an otherwise naïve host in vitro.

MreB is a bacterial homolog of actin and is postulated to perform critical roles in cell shape determination, coordination of cell division, protein localization, and chromosome segregation (18, 21, 25, 37). A series of novel S-benzylisothiourea compounds (29, 30), including S-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl) isothiourea (referred to as A22 and shown in Fig. 1), have been shown to perturb MreB function in E. coli and C. crescentus. Molecular genetic studies in the dimorphic bacterium C. crescentus, for example, have demonstrated a role for A22 in blocking MreB function, possibly by interacting directly with the MreB ATP binding pocket (25). In the studies presented here (Fig. 4A and B), we demonstrate that CBR-4830-resistant P. aeruginosa mreB missense mutants exhibit cross-resistance to A22 but with minimal overlap between specific alleles that were previously demonstrated to confer significant antimicrobial resistance to A22 in C. crescentus (25). While A22 and CBR-4830 are chemically distinct (Fig. 1), it appears from these limited, nonsaturating resistance studies that they share a similar binding site in MreB. Interestingly, A22, unlike CBR-4830 and related compounds (C7-0974 and C7-1007) described herein, does not appear to block polymerization of recombinant P. aeruginosa MreB in vitro (Table 3). As A22 has been shown to disperse existing MreB filaments in living cells within minutes (25), this result may be indicative of physical differences between our in vitro assay conditions and the in vivo setting or, alternately, that an additional factor(s) is required for A22 action in vivo. Clearly, the finding that two distinct chemical scaffolds appear to act on a single essential target in disparate microorganisms is a good indication of the potential “druggability” of MreB as a target for antibacterial development, as has previously been suggested (67).

Our inability to disrupt mreB unless a second functional copy of mreB is provided in trans is consistent with the idea that MreB performs an essential cellular function in P. aeruginosa and is not merely a structural scaffold required for maintaining rod shape. This conclusion is supported by the apparent failure of other researchers to recover P. aeruginosa mreB insertion mutants using saturating genome-wide transposon mutagenesis approaches (40). Based on the studies described herein, we cannot discern the nature of this essentiality or whether chemical perturbation of MreB function is bactericidal or bacteriostatic in nature. However, based on studies in other organisms, it is postulated that the lethal effects of MreB depletion (and hence CBR-4830 action) are multifactorial and likely result from failure to appropriately and faithfully segregate daughter chromosomes or from other consequences of loss of this crucial scaffold protein.

Use of efflux-compromised E. coli strains proved essential for uncovering the mode of action of a new class of bacterial RNA polymerase inhibitor (CBR-703) (1), and this systematic efflux knockout approach has been applied more broadly in studies with Streptococcus pneumoniae (57) and Haemophilus influenzae (64). We know of no other published studies wherein P. aeruginosa efflux-compromised strains have been systematically employed toward the discovery of novel classes of antipseudomonal agents. The results described substantiate the utility of the approach in the identification of novel discovery leads corresponding to compounds that would not have been discovered in screens employing efflux-proficient strains. Such compounds represent potential starting points for chemistry-based efforts to circumvent the efflux-based resistance mechanism while retaining target-directed antimicrobial activity. Although successful avoidance of the efflux liability was not observed for the small number of commercial analogs of CBR-4830 examined in these studies, there is precedence in the literature for the success of medicinal chemistry efforts to circumvent specific efflux mechanisms. For example, in the tetracycline and macrolides classes, semisynthetic chemistry efforts have yielded compounds of the so-called glycylcycline (10, 11, 50, 61) and ketolide classes (2, 9, 60, 70), respectively, that differ from their progenitors in no longer being substrates for key efflux pumps and therein retaining activity against clinical strains that exhibit efflux-based resistance. Specifically, tigecycline circumvents a series of major facilitator superfamily-class tetracycline-specific efflux proteins of both gram-negative and gram-positive pathogens (17, 50, 61), while telithromycin has significantly improved activity versus clinical isolates with elevated macrolide efflux via the MefA/E (23) and AcrAB systems (9). In the case of the fluoroquinolones, the overall hydrophilicity (3, 63) and bulk (26, 33, 34) of these compounds affect their sensitivity to specific efflux pumps, and the apparent structure-activity relationships delineated have contributed in the identification of novel development candidates that are less prone to efflux (49). Finally, studies of the effects of overexpression of the MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexXY-OprM systems on the efflux of a series of closely related carbapenem-class antibiotics has revealed intricate substrate specificities that could be further exploited in directed chemistry efforts (48). Hence, overall, there seems a reasonable expectation that targeted medicinal chemistry efforts may be undertaken to circumvent specific efflux mechanisms that limit the intracellular accumulation and therein activity of antibacterial discovery leads identified through screens employing efflux-defective strains. In the future, high-resolution structural studies of antimicrobial efflux components will likely also play a role in rational approaches to efflux avoidance. Finally, an alternate approach may be adopted wherein an efflux-compromised agent would be paired with an appropriately matched efflux pump inhibitor in a cocktail combination. Several such efflux pump inhibitors have been reported but have yet to be found to have true clinical utility, often owing to the narrow spectrum of pump recognition/inhibition or inappropriate pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters (42, 43).

Clearly, additional studies are needed to better understand the potential utility or liability of either approach toward the further advancement of antibacterial discovery leads like CBR-4830 for the development of new antipseudomonal agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank Greg Miller, Charles Ding, and Keith Combrink for their assistance; Peter Greenberg (University of Washington) for PAO1; and Herbert Schweizer (Colorado State University) for advice, strains, and reagents. Electron microscopy studies were undertaken by David Garrett at the University of North Texas Electron Microscope Facility.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Artsimovitch, I., C. Chu, A. S. Lynch, and R. Landick. 2003. A new class of bacterial RNA polymerase inhibitor affects nucleotide addition. Science 302:650-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asaka, T., A. Manaka, and H. Sugiyama. 2003. Recent developments in macrolide antimicrobial research. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 3:961-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beyer, R., E. Pestova, J. J. Millichap, V. Stosor, G. A. Noskin, and L. R. Peterson. 2000. A convenient assay for estimating the possible involvement of efflux of fluoroquinolones by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus: evidence for diminished moxifloxacin, sparfloxacin, and trovafloxacin efflux. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:798-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borges-Walmsley, M. I., K. S. McKeegan, and A. R. Walmsley. 2003. The structure and function of efflux pumps that confer resistance to drugs. Biochem. J. 376:313-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carballido-Lopez, R. 2006. The bacterial actin-like cytoskeleton. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70:888-909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi, K. H., J. B. Gaynor, K. G. White, C. Lopez, C. M. Bosio, R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, and H. P. Schweizer. 2005. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat. Methods 2:443-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi, K. H., and H. P. Schweizer. 2005. An improved method for rapid generation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa deletion mutants. BMC Microbiol. 5:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi, K. H., and H. P. Schweizer. 2006. Mini-Tn7 insertion in bacteria with single attTn7 sites: example Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat. Protoc. 1:153-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chollet, R., J. Chevalier, A. Bryskier, and J.-M. Pages. 2004. The AcrAB-TolC pump is involved in macrolide resistance but not in telithromycin eflux in Enterobacter aerogenes and Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3621-3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chopra, I. 2001. Glycylcyclines: third-generation tetracycline antibiotics. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 1:464-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chopra, I. 2002. New developments in tetracycline antibiotics: glycylcyclines and tetracycline efflux pump inhibitors. Drug Resist. Updates 5:119-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Chuanchuen, R., K. Beinlich, T. T. Hoang, A. Becher, R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, and H. P. Schweizer. 2001. Cross-resistance between triclosan and antibiotics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is mediated by multidrug efflux pumps: exposure of a susceptible mutant strain to triclosan selects nfxB mutants overexpressing MexCD-OprJ. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Chuanchuen, R., T. Murata, N. Gotoh, and H. P. Schweizer. 2005. Substrate-dependent utilization of OprM or OpmH by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa MexJK efflux pump. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2133-2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chuanchuen, R., C. T. Narasaki, and H. P. Schweizer. 2002. Benchtop and microcentrifuge preparation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa competent cells. BioTechniques 33:760, 762-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chuanchuen, R., C. T. Narasaki, and H. P. Schweizer. 2002. The MexJK efflux pump of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires OprM for antibiotic efflux but not for efflux of triclosan. J. Bacteriol. 184:5036-5044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2006. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 7th ed. Approved standard M7-A7. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 16.Coates, A., Y. Hu, R. Bax, and C. Page. 2002. The future challenges facing the development of new antimicrobial drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1:895-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dean, C. R., M. A. Visalli, S. J. Projan, P. E. Sum, and P. A. Bradford. 2003. Efflux-mediated resistance to tigecycline (GAR-936) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:972-978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Defeu Soufo, H. J., and P. L. Graumann. 2004. Dynamic movement of actin-like proteins within bacterial cells. EMBO Rep. 5:789-794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drlica, K., and X. Zhao. 2007. Mutant selection window hypothesis updated. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:681-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duncan, L., T. B. Doyle, Q. Du, J. Ehrhardt, A. S. Lynch, K. E. Mdluli, and G. T. Robertson. 2004. Construction of a novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain panel deficient in 52 potential drug efflux systems. Abstr. 44th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr D-1532.

- 21.Dye, N. A., Z. Pincus, J. A. Theriot, L. Shapiro, and Z. Gitai. 2005. Two independent spiral structures control cell shape in Caulobacter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:18608-18613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esue, O., M. Cordero, D. Wirtz, and Y. Tseng. 2005. The assembly of MreB, a prokaryotic homolog of actin. J. Biol. Chem. 280:2628-2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farrell, D. J., I. Morrissey, S. Bakker, L. Morris, S. Buckridge, and D. Felmingham. 2004. Molecular epidemiology of multiresistant Streptococcus pneumoniae with both erm(B)- and mef(A)-mediated macrolide resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:764-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Figge, R. M., A. V. Divakaruni, and J. W. Gober. 2004. MreB, the cell shape-determining bacterial actin homologue, coordinates cell wall morphogenesis in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1321-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gitai, Z., N. A. Dye, A. Reisenauer, M. Wachi, and L. Shapiro. 2005. MreB actin-mediated segregation of a specific region of a bacterial chromosome. Cell 120:329-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gould, K. A., X.-S. Pan, R. J. Kerns, and L. M. Fisher. 2004. Ciprofloxacin dimers target gyrase in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2108-2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirata, T., A. Saito, K. Nishino, N. Tamura, and A. Yamaguchi. 2004. Effects of efflux transporter genes on susceptibility of Escherichia coli to tigecycline (GAR-936). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2179-2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoang, T. T., R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, A. J. Kutchma, and H. P. Schweizer. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwai, N., T. Fujii, H. Nagura, M. Wachi, and T. Kitazume. 2007. Structure-activity relationship study of the bacterial actin-like protein MreB inhibitors: effects of substitution of benzyl group in S-benzylisothiourea. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71:246-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwai, N., K. Nagai, and M. Wachi. 2002. Novel S-benzylisothiourea compound that induces spherical cells in Escherichia coli probably by acting on a rod-shape-determining protein(s) other than penicillin-binding protein 2. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 66:2658-2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones, L. J., R. Carballido-Lopez, and J. Errington. 2001. Control of cell shape in bacteria: helical, actin-like filaments in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 104:913-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karczmarek, A., R. M. Baselga, S. Alexeeva, F. G. Hansen, M. Vicente, N. Nanninga, and T. den Blaauwen. 2007. DNA and origin region segregation are not affected by the transition from rod to sphere after inhibition of Escherichia coli MreB by A22. Mol. Microbiol. 65:51-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerns, R. J., M. J. Rybak, G. W. Kaatz, F. Vaka, R. Cha, R. G. Grucz, and V. U. Diwadkar. 2003. Structural features of piperazinyl-linked ciprofloxacin dimers required for activity against drug-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13:2109-2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerns, R. J., M. J. Rybak, G. W. Kaatz, F. Vaka, R. Cha, R. G. Grucz, V. U. Diwadkar, and T. D. Ward. 2003. Piperazinyl-linked fluoroquinolone dimers possessing potent antibacterial activity against drug-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13:1745-1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kohler, T., M. Michea-Hamzehpour, U. Henze, N. Gotoh, L. K. Curty, and J. C. Pechere. 1997. Characterization of MexE-MexF-OprN, a positively regulated multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 23:345-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kriengkauykiat, J., E. Porter, O. Lomovskaya, and A. Wong-Beringer. 2005. Use of an efflux pump inhibitor to determine the prevalence of efflux pump-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance and multidrug resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:565-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kruse, T., B. Blagoev, A. Lobner-Olesen, M. Wachi, K. Sasaki, N. Iwai, M. Mann, and K. Gerdes. 2006. Actin homolog MreB and RNA polymerase interact and are both required for chromosome segregation in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 20:113-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kruse, T., J. Moller-Jensen, A. Lobner-Olesen, and K. Gerdes. 2003. Dysfunctional MreB inhibits chromosome segregation in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 22:5283-5292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li, X., M. Zolli-Juran, J. D. Cechetto, D. M. Daigle, G. D. Wright, and E. D. Brown. 2004. Multicopy suppressors for novel antibacterial compounds reveal targets and drug efflux susceptibility. Chem. Biol. 11:1423-1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liberati, N. T., J. M. Urbach, S. Miyata, D. G. Lee, E. Drenkard, G. Wu, J. Villanueva, T. Wei, and F. M. Ausubel. 2006. An ordered, nonredundant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 transposon insertion mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:2833-2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Llanes, C., D. Hocquet, C. Vogne, D. Benali-Baitich, C. Neuwirth, and P. Plesiat. 2004. Clinical strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa overproducing MexAB-OprM and MexXY efflux pumps simultaneously. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1797-1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lomovskaya, O., and K. A. Bostian. 2006. Practical applications and feasibility of efflux pump inhibitors in the clinic—a vision for applied use. Biochem. Pharmacol. 71:910-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lynch, A. S. 2006. Efflux systems in bacterial pathogens: an opportunity for therapeutic intervention? An industry view. Biochem. Pharmacol. 71:949-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mine, T., Y. Morita, A. Kataoka, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 1999. Expression in Escherichia coli of a new multidrug efflux pump, MexXY, from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:415-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mukherjee, A., and J. Lutkenhaus. 1999. Analysis of FtsZ assembly by light scattering and determination of the role of divalent metal cations. J. Bacteriol. 181:823-832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nikaido, H., and H. I. Zgurskaya. 1999. Antibiotic efflux mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 12:529-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nilsen, T., A. W. Yan, G. Gale, and M. B. Goldberg. 2005. Presence of multiple sites containing polar material in spherical Escherichia coli cells that lack MreB. J. Bacteriol. 187:6187-6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okamoto, K., N. Gotoh, and T. Nishino. 2002. Alterations of susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by overproduction of multidrug efflux systems, MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexXY/OprM to carbapenems: substrate specificities of the efflux systems. J. Infect. Chemother. 8:371-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel, M. V., N. J. De Souza, S. V. Gupte, M. A. Jafri, S. S. Bhagwat, Y. Chugh, H. F. Khorakiwala, M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 2004. Antistaphylococcal activity of WCK 771, a tricyclic fluoroquinolone, in animal infection models. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4754-4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petersen, P. J., P. A. Bradford, W. J. Weiss, T. M. Murphy, P. E. Sum, and S. J. Projan. 2002. In vitro and in vivo activities of tigecycline (GAR-936), daptomycin, and comparative antimicrobial agents against glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus and other resistant gram-positive pathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2595-2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poole, K. 1994. Bacterial multidrug resistance—emphasis on efflux mechanisms and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 34:453-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poole, K. 2004. Efflux-mediated multiresistance in gram-negative bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10:12-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poole, K. 2002. Mechanisms of bacterial biocide and antibiotic resistance. Symp. Ser. Soc. Appl. Microbiol. 31:55S-64S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poole, K., N. Gotoh, H. Tsujimoto, Q. Zhao, A. Wada, T. Yamasaki, S. Neshat, J. Yamagishi, X. Z. Li, and T. Nishino. 1996. Overexpression of the mexC-mexD-oprJ efflux operon in nfxB-type multidrug-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 21:713-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poole, K., and R. Srikumar. 2001. Multidrug efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: components, mechanisms and clinical significance. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 1:59-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Projan, S. J. 2002. New (and not so new) antibacterial targets: from where and when will the novel drugs come? Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2:513-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robertson, G. T., T. B. Doyle, and A. S. Lynch. 2005. Use of an efflux-deficient Streptococcus pneumoniae strain panel to identify ABC-class multidrug transporters involved in intrinsic resistance to antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4781-4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schweizer, H. P. 2003. Efflux as a mechanism of resistance to antimicrobials in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and related bacteria: unanswered questions. Genet. Mol. Res. 2:48-62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schweizer, H. P. 2001. Vectors to express foreign genes and techniques to monitor gene expression in pseudomonads. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 12:439-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shortridge, V. D., P. Zhong, Z. Cao, J. M. Beyer, L. S. Almer, N. C. Ramer, S. Z. Doktor, and R. K. Flamm. 2002. Comparison of in vitro activities of ABT-773 and telithromycin against macrolide-susceptible and -resistant streptococci and staphylococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:783-786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Someya, Y., A. Yamaguchi, and T. Sawai. 1995. A novel glycylcycline, 9-(N,N-dimethylglycylamido)-6-demethyl-6-deoxytetracycline, is neither transported nor recognized by the transposon Tn10-encoded metal-tetracycline/H+ antiporter. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:247-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Srinivasan, R., M. Mishra, M. Murata-Hori, and M. K. Balasubramanian. 2007. Filament formation of the Escherichia coli actin-related protein, MreB, in fission yeast. Curr. Biol. 17:266-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takenouchi, T., F. Tabata, Y. Iwata, H. Hanzawa, M. Sugawara, and S. Ohya. 1996. Hydrophilicity of quinolones is not an exclusive factor for decreased activity in efflux-mediated resistant mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1835-1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trepod, C. M., and J. E. Mott. 2004. Identification of the Haemophilus influenzae tolC gene by susceptibility profiles of insertionally inactivated efflux pump mutants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1416-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Bambeke, F., Y. Glupczynski, P. Plesiat, J. C. Pechere, and P. M. Tulkens. 2003. Antibiotic efflux pumps in prokaryotic cells: occurrence, impact on resistance and strategies for the future of antimicrobial therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:1055-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van den Ent, F., L. A. Amos, and J. Lowe. 2001. Prokaryotic origin of the actin cytoskeleton. Nature 413:39-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vollmer, W. 2006. The prokaryotic cytoskeleton: a putative target for inhibitors and antibiotics? Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 73:37-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.West, S. E., H. P. Schweizer, C. Dall, A. K. Sample, and L. J. Runyen-Janecky. 1994. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 148:81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Westbrock-Wadman, S., D. R. Sherman, M. J. Hickey, S. N. Coulter, Y. Q. Zhu, P. Warrener, L. Y. Nguyen, R. M. Shawar, K. R. Folger, and C. K. Stover. 1999. Characterization of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa efflux pump contributing to aminoglycoside impermeability. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2975-2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhanel, G. G., T. Hisanaga, K. Nichol, A. Wierzbowski, and D. J. Hoban. 2003. Ketolides: an emerging treatment for macrolide-resistant respiratory infections, focusing on S. pneumoniae. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 8:297-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ziha-Zarifi, I., C. Llanes, T. Kohler, J. C. Pechere, and P. Plesiat. 1999. In vivo emergence of multidrug-resistant mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa overexpressing the active efflux system MexA-MexB-OprM. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:287-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]