Abstract

The ribosomal 50S subunit protein L9, encoded by the gene rplI, is an elongated protein with an α-helix connecting the N- and C-terminal globular domains. We isolated rplI mutants that suppress the +1 frameshift mutation hisC3072 in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. These mutants have amino acid substitutions in the N-terminal domain (G24D) or in the C-terminal domain (I94S, A102D, G126V, and F132S) of L9. In addition, different one-base deletions in rplI altered either the final portion of the C terminus or removed the C-terminal domain with or without the connecting α-helix. An alanine-to-proline substitution at position 59 (A59P), which breaks the α-helix between the globular domains, induced +1 frameshifting, suggesting that the geometrical relationship between the N and C domains is important to maintain the reading frame. Except for the alterations G126V in the C terminus and A59P in the connecting α-helix, our results confirm earlier results obtained by using the phage T4 gene 60-based system to monitor bypassing. The way rplI mutations suppress various frameshift mutations suggests that bypassing of many codons from several takeoff and landing sites occurred instead of a specific frameshift forward at overlapping codons.

During protein synthesis, mRNA and tRNA move in a coordinated way through the ribosome. This coordination is dependent on the formation and maintenance of cognate codon-anticodon pairing. Once established in the ribosomal A-site, the tRNA-mRNA interaction is maintained in the ribosomal P-site and stabilized via extensive contacts between the ribosome and tRNA (23, 33). However, occasionally this process fails and an error in the reading frame maintenance occurs. Spontaneous frameshift events are very infrequent, probably fewer than 10−5 per codon (24). However, the frequency can be affected by certain sequences in the mRNA, altered tRNAs, and ribosomal mutants. Certain physiological conditions that most likely change the balance between the various components of the translation machinery also induce errors in the reading frame maintenance (7-9, 11).

Changes in the reading frame can either be one step backward (−1) or one step forward (+1) by the ribosome. However, the ribosome may also detach from one codon (takeoff site) and resume translation downstream at another codon (landing site) and in such a way bypass many codons (15). One of the most intriguing examples of bypassing occurs during translation of the bacteriophage T4 gene 60 mRNA, which encodes a subunit of T4 topoisomerase, when the ribosome-bound peptidyl-tRNA disengages from the glycine codon GGA at position 46 and reengages on an identical GGA codon 50 nucleotides downstream (20). T4 gene 60 mRNA and translated nascent peptide contain several stimulatory signals facilitating this hop. Alteration in these signals reduces or eliminates bypassing. On the other hand, this effect can be counteracted by mutations in ribosomal protein L9 (15), implying that the wild-type form of L9 prevents initiation of bypassing, and its presence may be important for reading frame maintenance in general.

Genetic analysis of ribosomal reading frame maintenance is founded on the analysis of suppression of frameshift mutations, which are created by either addition or deletion of nucleotides in the gene sequence. Such changes in the sequence result in an out-of-frame translation of the mRNA and in most cases the production of a nonfunctional protein. Correction of the phenotype is possible if the ribosome slips to the original reading frame. One such frameshift mutation (hisC3072) has been used in this work. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium carrying this mutation is unable to grow without the addition of histidine (i.e., it has a His− phenotype). If the ribosome translating hisC3072 mRNA slips into the +1 frame, synthesis of a functional HisC protein occurs, and the bacterium becomes His+. We have exploited this phenomenon to isolate external suppressors inducing ribosomal slippage to the +1 frame. One class of mutants obtained by such a selection was defective in  , resulting in either a reduced concentration of the tRNA or a reduced arginylation of it. It was proposed that inefficient decoding of the AGA codon by the defective

, resulting in either a reduced concentration of the tRNA or a reduced arginylation of it. It was proposed that inefficient decoding of the AGA codon by the defective  stalls the ribosome at the A-site codon, allowing the wild-type form of the peptidyl

stalls the ribosome at the A-site codon, allowing the wild-type form of the peptidyl  to slip forward one nucleotide and thereby reestablish the ribosome in the zero frame (25). Another class of +1 frameshift suppressor mutants, which are analyzed here, shows that the ribosomal 50S subunit protein L9 plays an important role in reading frame maintenance, in support of earlier observations (15). We describe mutations such as amino acid substitutions in the C or N terminus, various degrees of truncation, and even the total absence of L9 that cause the ribosome to slip probably without any other stimulatory signals. Interestingly, a break in the α-helix connecting the N- and C-terminal globular domains of L9 induces frameshifting, suggesting that the geometrical relationship between these globular domains is important for L9 function in maintaining the reading frame.

to slip forward one nucleotide and thereby reestablish the ribosome in the zero frame (25). Another class of +1 frameshift suppressor mutants, which are analyzed here, shows that the ribosomal 50S subunit protein L9 plays an important role in reading frame maintenance, in support of earlier observations (15). We describe mutations such as amino acid substitutions in the C or N terminus, various degrees of truncation, and even the total absence of L9 that cause the ribosome to slip probably without any other stimulatory signals. Interestingly, a break in the α-helix connecting the N- and C-terminal globular domains of L9 induces frameshifting, suggesting that the geometrical relationship between these globular domains is important for L9 function in maintaining the reading frame.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used were derivatives of S. enterica (Table 1). As rich media, we used either Luria-Bertani medium (2) or the complex medium NAA (Difco nutrient broth [0.8%]; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI), supplemented with aromatic amino acids, aromatic vitamins, and adenine (6). The minimal solid medium was made from the basal medium E (41) with 15 g of agar per liter and supplemented with 0.2% glucose and required amino acids or vitamins (6). TYS-agar (10 g of Trypticase peptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 5 g of NaCl, and 15 g of agar per liter) was used as solid rich medium.

TABLE 1.

S. enterica strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotypea | Source |

|---|---|---|

| LT2 | Wild type | J. Roth |

| GT5167 | hisO1242 hisC3072 vacB2530::Tn10dTc rplI2(G24D) | This study |

| GT6861 | zjf-2531<>cat/pSMP24 | This study |

| GT6947 | hisO1242 hisC3072 zjf-2531<>cat rplI1 (L6-3aa-STOP)* | This study |

| GT6949 | hisO1242 hisC3072 zjf-2531<>cat rplI3 (T40-62aa-STOP)* | This study |

| GT6951 | hisO1242 hisC3072 zjf-2531<>cat rplI4 (K42-60aa-STOP)* | This study |

| GT6953 | hisO1242 hisC3072 zjf-2531<>cat rplI5 (A74-28aa-STOP)* | This study |

| GT6955 | hisO1242 hisC3072 zjf-2531<>cat rplI6 (I94S) | This study |

| GT6957 | hisO1242 hisC3072 zjf-2531<>cat rplI7 (A102D) | This study |

| GT6959 | hisO1242 hisC3072 zjf-2531<>cat rplI8 (G126V) | This study |

| GT66961 | hisO1242 hisC3072 zjf-2531<>cat rplI9 (F132S) | This study |

| GT6863 | hisO1242 hisC3072 zjf-2531<>cat rplI10 (E137-33aa-STOP)* | This study |

| GT6989 | hisO1242 hisC3072 rplI11<>cat | This study |

| GT6990 | hisO1242 hisC3072 rplI11<>cat/pUST274 | This study |

| GT7216 | hisO1242 hisC3072 rplI13<>tetRA | This study |

| GT7542 | hisO1242 hisC3072 rplI12 (A59P) | This study |

| TR947 | (GT885) hisO1242 hisC3072 | J. Roth |

*, In the rplI1, rplI3, rplI4, rplI5, and rplI10 mutants the last correct amino acid and the number of aberrantly inserted amino acids due to frameshift mutation in the gene sequence are indicated in parentheses. “<>” denotes an insertion. The chromosomal location of the insertion is indicated on the left, and the name of the inserted gene is indicated on the right.

Genetic procedures.

Transduction with phage P22 HT105/1 (int-201) (37) was performed as previously described (6).

DNA sequencing was performed on chromosomal DNA or PCR products according to the manual of Applied Biosystems for ABI Prism cycle sequencing ready reaction kit and BigDye. Mutagenesis of the strain GT6861 (zjf-2531<>cat/pSMP24) was performed by inducing the expression of DinB (42, 43) from plasmid pSMP24 (29). DinB is a DNA polymerase (DNA Pol IV) mediating template-directed DNA replication but lacking 3′-to-5′ proofreading activity. This leads to untargeted mutagenesis and single-base substitutions, as well as one-base deletions (43). Five overnight cultures of zjf-2531<>cat/pSMP24 were diluted (2 × 106)-fold and inoculated into 500 μl of Luria-Bertani broth plus 100 μg of carbenicillin/ml and 0.08% l-arabinose to induce DinB synthesis and initiate mutagenesis. After 24 h of growth at 37°C with agitation, phage P22 was added to make phage lysates of each of the five cultures. The phage lysates were used to infect the His− strain GT885 (hisO1242 hisC3072). Chloramphenicol-resistant (Cmr) transductants were selected on plates containing TYS plus 12.5 μg of Cm/ml and 10 mM EGTA and printed onto plates containing minimal E plus 0.2% glucose and 12.5 μg of Cm/ml. His+ clones were collected every day for 9 days and saved for further analysis. A total of 50,000 Cmr transductants were screened for the His+ phenotype. Known suppressors of the frameshift mutation hisC3072 induce frameshifting that is only 1% efficient but can be isolated as His+ clones after 48 h of incubation at 37°C (35). The hisD3018 allele is suppressed by the sufB2 frameshift suppressor, also operating with an efficiency of only 1% (44), and such His+ clones are detected after 24 h of incubation at 37°C (data not shown). Thus, the His+ selection method used here will detect suppressor mutants with the suppression efficiency of only a fraction of a percent.

The deletion mutant rplI11<>cat was constructed by inserting a PCR fragment carrying the Cmr gene cat between the first and last sense codons of the rplI gene, fully eliminating the rplI coding sequence (5). The same method was used to create the zjf-2531<>cat insertion but without deleting any chromosomal sequences. To make the A59P alteration in L9, the tetracycline resistance (Tcr) (tetRA) cassette was introduced between the codons for amino acids D60 and V61 on the chromosome as described previously (5), generating strain GT7216 (hisO1242 hisC3070 rplI11<>tetRA). Next, we electroporated a 75-nucleotide-long oligonucleotide homologous to the wild-type sequence of rplI in this area, except for the desired mutation [GCT(Ala)-to-CCT(Pro) codon change at position 59] in the middle of the oligo. Tcs clones were selected on plates, on which only Tcs, but not Tcr, clones can grow, as described earlier (30). The obtained GCT-to-CCT change in the rplI gene was verified by DNA sequencing.

Plasmid pUST274 was constructed by cloning a DNA fragment containing the frameshift sequence into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of vector pGHM57 (16). The DNA fragment was made from two complementary oligonucleotides (5′-TTTGGATCCCGGGGGAAAGACGCCATTCTCTACTGTCCGAATTCTTT T-3′ and 5′-AAAAGAATTCGGACAGTAGAGAATGGCGTCTTTCCCCCGGGATCCAAA-3′; BamHI and EcoRI sites are in italics), and the ends were trimmed with BamHI and EcoRI endonucleases. Ligated plasmids were transformed into strain DH5α, analyzed by sequencing the insert and retransformed by electroporation into different S. enterica strains.

Protein analysis.

To monitor ribosomal slippage and to purify the slippage product, a previously described system was used (13, 16). This system employs a fusion protein consisting of maltose-binding protein (MBP) fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST) at its N terminus and having six histidine residues (His6) at the carboxy terminus (GST-MBP-His6). Plasmid pUST274 contained an insert, resembling the frameshifting site present in hisC3072, at the fusion point between the gst and malE genes that encode the GST and MBP proteins, respectively. The frameshift window relevant for the experiment is shown in the legend to Fig. 2. Production of complete fusion proteins (∼70 kDa) required translational slippage to the +1 frame, whereas if no slippage occurred translation terminated after the gst gene, producing only GST (26 kDa). The two forms of protein were confirmed by Western blot analysis with anti-GST-HRP conjugate and ECL Plus detection reagents from Amersham Biosciences. The full-length GST-MBP-His6 fusion protein was purified by passing the protein extract over glutathione-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) and then over Ni-NTA-agarose (QIAGEN). To strip the GST part from the frameshift product, purified GST-MBP-His6 was digested by PreScission protease (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), cleaving the site directly after the GST moiety. Digestion products were fractionated by gel electrophoresis and the 43-kDa peptide, corresponding to the slippage junction fused to MBP-His6, was subjected to N-terminal sequencing by Edman degradation.

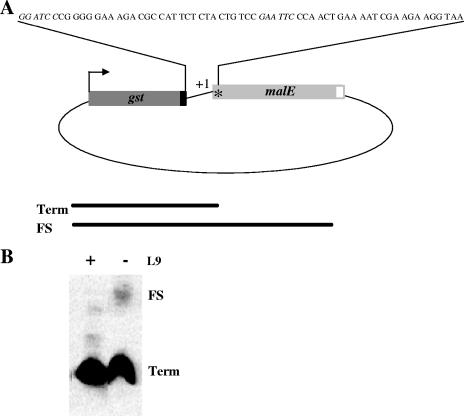

FIG. 2.

pUST274 plasmid construct carrying the +1 frameshift site. (A) The malE gene is in the +1 frame relative to the gst gene. The PreScission protease recognition site in the 3′ terminus of gst sequence is indicated as a black box, the first stop codon (TAA) encountered in the 0 frame in malE is marked by an asterisk, and the His6 tag is indicated as a white box. The total length of the frameshift window generating the GST-MalE fusion is: AAG-TAT-ATA-GCA-TGG-CCT-TTG-CAG-GGC-TGG-CAA-GCC-ACG-TTT-GGT-GGT-GGC-GAC-CAT-CCT-CCA-AAA-TCG-GAT-CTG-GAA-GTT-CTG-TTC-CAG-GGT-CCA-CTC-GGG-ATC-CCG-GGG-GAA-AGA-CGC-CAT-TCT-CTA-CTG- TCC-GAA-TTC-CCA-ACT-GAA-AAT-CGA-AGA-AGG-TAA. The UAG and UAA stop codons in +1 and 0 frame, respectively, are in boldface. The underlined portion is the sequence corresponding to the N-terminal sequence generated following digestion by PreScission protease as also shown in the panel. The BamHI and EcoRI sites used for inserting the desired frameshift site are indicated in italics. (B) Frameshifting (FS) and termination (Term) products from the wild type and rplI11<>Cmr mutant separated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate gel and detected by anti-GST antibodies by Western blot analysis.

RESULTS

Isolation of frameshift suppressor mutations in the rplI gene coding for ribosomal protein L9.

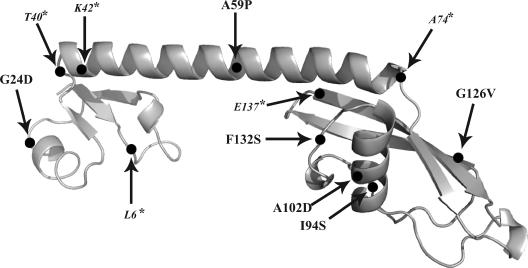

The hisC3072 mutant contains a G insertion in a run of G's: GGG GAA AGA (NNN)29 UGA [presented as the zero frame following the insertion; the inserted G is underlined, and (NNN)29 stands for 29 sense codons] and is therefore auxotrophic for histidine (25). External suppressors rendering the hisC3072 mutant able to grow without addition of histidine were selected. The isolated suppressors were expected to induce ribosomal slippage to the +1 frame while translating the hisC3072 mRNA. To obtain such external suppressors, a phage P22 lysate of a random Tn10dTc insertion pool in the wild-type strain LT2 was treated with the mutagen hydroxylamine (19) and used to infect strain TR947 (GT885; hisO1242 hisC3072). Tcr clones were first selected and, among these, His+ clones were selected. One such Tcr His+ transductant was selected for further analysis. The location of the Tn10dTc insertion was determined first by sequencing the chromosomal regions flanking the insertion point, and the sequence showed that the transposon was in the coding region of the vacB gene, vacB2530::Tn10dTc. Later, transductional mapping indicated that the suppressor mutation was only 7% linked to and situated clockwise of the vacB2530::Tn10dTc insertion. To further map the mutation inducing the His+ phenotype, a Cmr cassette (denoted zjf-2531<>cat) was inserted into the noncoding DNA region between the genes sgaE and yjfY, 18 kb from vacB. Since the zjf-2531<>cat insertion appeared to be 99% linked to the mutation inducing His+ phenotype, we explored the neighboring genes. The closest operon contained genes rpsF, rpsR, and rplI coding for the ribosomal proteins S6, S18, and L9, respectively. This operon was sequenced, and the suppressor of the frameshift mutation hisC3072 was located to the gene rplI, resulting in an amino acid substitution G24D in the N domain of L9 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Alterations in protein L9. The presented protein structure shows L9 from Bacillus (18). The N- and C-terminal globular domains are to the left and right, respectively, with the connecting α-helix in between. Since protein L9 in Bacillus and Salmonella is conserved, the indicated mutation sites are numbered according to L9 of Salmonella. The amino acid substitutions are in boldface; the frameshift mutations are in italics. An asterisk with the amino acid symbol marks the codon in which it occurred.

Creation of new mutations in the gene rplI.

It was of interest to test whether +1 frameshifting on hisC3072 mRNA could be induced by other L9 mutants. Mutations in strain GT6861 (zjf-2531::cat/pSMP24) were therefore induced by overexpression of the dinB gene, and mutations that were closely linked to the zjf-2531<>cat and that suppressed the His− phenotype of TR947(hisO1242 hisC3072) were collected. Nine such clones were obtained. The rplI gene was sequenced in all of them, and several single-nucleotide substitutions, as well as several one-nucleotide deletions, were identified. Altogether, the original rplI2 mutation and later-characterized mutations had amino acid substitutions in the N domain (G24D) or the C domain (I94S, A102D, G126V, and F132S) of L9, and they primarily affected conserved structural elements of the protein (Fig. 1). Different frameshift mutations in rplI altered either the extreme portion of the C terminus or induced truncations in the C-terminal domain with or without the connecting α-helix of L9 (Fig. 1). A deletion mutant of rplI (rplI11<>cat) was also created by replacing the coding sequence with the Cmr cassette, proving again that the L9 is not an essential protein. Under standard lab conditions bacteria lacking L9 showed no detectable growth impairment. However, the rplI11<>cat mutation was suppressing His− phenotype of hisC3072 containing mutant. Since the rplI gene is the last gene in the operon, the induced His+ phenotype could not be related to a potential polar effect of Cmr cassette's insertion. Thus, a frameshift mutation in hisC3072 could be suppressed by a variety of mutations in ribosomal protein L9, ranging from amino acid substitutions to truncations that alter its function or prevent incorporation into the ribosome, and even by the absence of L9. All of these mutations suppressed the hisC3072 mutation, as judged by growth on plates lacking histidine (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Suppression of the hisC3072 mutation by different rplI mutations

| rplI alleles | Position of alteration in L9 | Growth on minimal medium without histidinea |

|---|---|---|

| rplI+ | Not relevant | - |

| rplI (L6-3aa-stop) | N terminal | + |

| rplI2 (G24D) | N terminal | + |

| rplI6 (I94S) | C terminal | + |

| rplI8 (G126V) | C terminal | + |

| rplI9 (F132S) | C terminal | + |

| rplI11<>cat | Not relevant | + |

| rplI12 (A59P) | α-Helix | (+) |

That is, suppression. +, Growth; (+), weak growth; -, no growth. Values were determined after 2 days of incubation at 37°C.

The geometrical relationship between the two globular domains of L9 is important to prevent +1 frameshifting.

In the intact 70S ribosome, the N-terminal domain of L9 binds to the ribosome below the L1 stalk, whereas the C-terminal domain extends more than 50 Å from the surface of the 50S subunit due to the presence of a rigid α-helix connecting the N- and C-terminal domains (45). The connecting α-helix of conserved length was suggested to improve the reading frame maintenance by determining a proper spacing between ribosomes on the mRNA (16) or looping back to interact with the ribosome, to which its N-terminal end is bound, as demonstrated by footprinting data (27) and by cryo-electron microscopy (31). To test the role of the α-helix in frameshifting, an amino acid substitution was made in the middle of it. The Ala59-to-Pro59 change was predicted to break the a α-helix and therefore alter the relative orientation of globular domains flanking the helix. Since in such a mutant the RNA-binding properties of individual domain remain unchanged, the A59P mutant L9 might still be binding, at least partially, to the ribosome. The L9 with broken α-helix induced a +1 frameshift, albeit weaker than the suppression mediated by the other alterations of L9 (Table 2). These data suggest that even a small aberration of the conserved connecting α-helix of L9 induce errors in maintaining the correct reading frame.

Characterization of ribosomal frameshift product in a mutant lacking L9.

Plasmid pUST274 was used to analyze ribosomal shifts to the +1 frame. This plasmid codes for a GST-MBP-His6 fusion protein with a coding sequence changing frame, similar to that present in hisC3072, between the genes for GST and MBP. A complete GST-MBP-His6 fusion protein was only synthesized when the ribosome was shifted to the +1 frame. Alternatively, translation terminated at the UAA stop codon found downstream of the frameshift sequence, producing only the GST moiety (Fig. 2A). Total protein extracts were prepared from the rplI11<>cat deletion mutant and the wild type, both containing plasmid pUST274. The termination product and the complete fusion protein were analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 2B). The protein extract obtained from the strain lacking L9 had a band corresponding to complete fusion protein, which was absent in the wild type. However, we noticed that this protein was not forming a sharp band on the gel, suggesting that the product was not homogenous. Using the GST and His6 affinity tags, we purified the fusion protein from the hisO1242 his3072 rplI11<>cat/pUST274 strain and digested it with PreScission protease. The resulting liberated slippage junction fused to the MBP-His6 was subjected to N-terminal sequencing. However, two trials resulted in two different mixed amino acid sequences, with none of them resembling a peptide as deduced from the tested frameshift DNA sequence. These results suggest that if one base frameshift occurs at overlapping codons it must occur on multiple sites. Alternatively, the results are consistent with bypassing using various takeoff and landing sites as L9 was earlier shown to induce (15).

The +1 frameshifts mediated by defective ribosomal protein L9 require a long frameshift window.

Since the amino acid sequence of the slippage junction peptide indicated a lack of specificity for ribosomal frameshifting when L9 was absent, we tested whether those mutant ribosomes suppressed other frameshift mutations. The rplI2 (G24D) mutation was therefore introduced into strains carrying various frameshift mutations in different his genes, rendering them His−, and the double mutants were monitored for the ability to grow without the addition of histidine. Of 15 his mutations, only four were suppressed: hisB6480, hisD2780, hisF2439, and hisC3072 (Table 3). The hisB6480 and hisD2780 mutations have a characteristic run of C's and are suppressed by sufA, which induces frameshifting at such CCC sites (36). The hisF2439 and hisC3072 mutations have a characteristic run of G's and are suppressed by sufD, which induces frameshifts at GGG sites (34). However, the other five CCC-containing sites and three GGG-containing sites were still His− in the presence of the rplI2 mutation. These results indicated the absence of specificity for suppression of runs of C's or G's mediated by an altered L9. Nevertheless, the suppressed frameshift mutants had one feature in common, since in all of them the frameshift window was at least 31 codons long. A long frameshifting window increases the probability for the ribosome to shift frame at multiple places or to bypass several codons before the stop codon is reached. Of course, this requires that produced protein tolerates short portions of aberrantly inserted amino acids without losing its function. The frameshift window in the hisD3068 mutant is of 42 codons but was not suppressed by the rplI2 mutation. This could be explained because the third codon downstream the G insertion point is coding for conserved His326 involved in the catalysis reaction performed by HisD (40). The mutated HisD produced by the double hisD3068 rplI2 mutant most likely has Thr326 instead, and therefore the strain was His−. Similarly, the hisG3037 frameshift mutant (containing a 26-codon-long frameshifting window) was not suppressed by rplI2 because the G insertion point is located adjacent to and 3′ of the sequence coding for the conserved 13-amino-acid-long binding site for 5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate, which is one of the substrates for HisG (28). HisG may not tolerate amino acid changes at this site, and the mutated HisG produced after rplI2 suppression may not be active. The hisD3018, hisD6610, hisD3749, hisD6580, and hisF6527 mutants have short frameshift windows of four to eight codons, and none of them was suppressed by rplI2 (Table 3). The hisD3749 mutation is located only 13 codons from the N-terminal end, which can sustain various amino acid substitutions without affecting the activity of HisD (12, 21), and still it was not suppressed by the rplI2 mutation. We conclude that mutations in rplI suppressed all tested his mutants that had long frameshifting windows located in the sequences coding for nonessential parts of the proteins. The requirement for a long frameshift window is consistent with ribosomal bypassing, where more than one takeoff and landing site could be used, as has been shown earlier for ribosomes with defective L9 (15). Apparently, an altered L9 can induce ribosomal frameshifting without any other stimulatory signals present on the mRNA.

TABLE 3.

Suppressor specificity of different frameshift sites monitored by growth on medium lacking histidine

| his alleles | Frameshift windowsa

|

Frameshift suppressorb

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence | No. of codons | sufA | sufB | sufD | sufF | rplI2 | |

| hisD3018 | gug aca gcg cua cgc guc acc cccuga | 7 | + | + | - | - | - |

| hisC3737 | gta gag cgc cgg acg gtt ccc gcg ctt gaa aac tgg cag ctg gat cta cag ggg att tcc gac aac ctt gac ggc aca aaa gtg gtg ttc gtt tgt agc ccc caa taa | 34 | + | + | - | - | - |

| hisD3749 | cug auu gac ugg aac agc ugu agc cccuga | 8 | + | + | - | - | - |

| hisD6610 | gtg aca gcg cua cgc guc acaccc cccuga | 8 | + | + | - | ND | - |

| hisB6480 | atg atc act aac cag gat gga ctt ggc acg caa agg ctt ccc gca ggc gga ctt cga cgg acc gca caa cct gat gat gca gat ttt cac ctc tca ggg cgt atg ctt tga tga | 36 | + | - | - | ND | + |

| hisD2780 | ctg atg ctg gcg acg ccg gcg cgc att gcg gga tgc cag aag gtg gtt ctg tgc tcg ccg ccg ccc atc gct gat gaa atc ctc tat gcg gcg caa ctg tgt ggc gtg cag gaa atc ttt aac gtc ggc ggc gcg cag gcg att gcc gct ctg gcc ttc ggc agc gag tcc gta ccg aaa gtg gat aaa att ttt ggc ccc cgg caa cgc ctt tgt aac cga agc caa acg tca ggt cag cca gcg tct cga cgg cgc ggc tat cga tat gcc agc cgg gcc gtc tga | 94 | + | ND | - | ND | (+) |

| hisD3040 | gtg atc gca gac agc ggc gca aca ccg gat ttc gtc gct tct gac ctg ctc tcc cag gct gag cac ggc ccc gga ttc cca ggt gat cct gct gac gcc tga | 32 | + | ND | - | ND | - |

| hisF2439 | gtg acg cag tgg gag acg ctg gac tgg gtg caa gag gta caa cag cgc ggc gcg ggg gga aat cgt cct gaa tat gat gaa cca gga cgg cgt gcg taa | 31 | - | - | + | - | + |

| hisF3704 | ctg att acc cgt ctg gct gac cgt ttt ggc gta cag tgt att gtc gtc ggg att gat acc tgg ttt gac gac gcc acg ggg gaa ata cca tgt taa | 30 | - | - | + | - | - |

| hisC3072 | gtg atc cgc gcc ttc tgt gaa ccg ggg gaa aga cgc cat tct cta ctg tcc gcc cac tta cgg tat gta cag cgt cag cgc cga aac cat tgg cgt aga gcg ccg gac ggt tcc cgc gct tga | 39 | - | - | + | + | + |

| hisD3068 | ctg att gtg acc aaa gat tta gcg cag tgc gtc gcc atc tct aat cag tat ggg gcc gga aca ctt aat cat cca gac gcg caa tgc gcg cga ttt ggt gga tgc gat tac cag cgc agg ctc ggt att tct cgg cga ctg gtc gcc gga atc cgc cgg tga | 42 | - | - | + | ND | - |

| hisG3037 | tta aat ggt tct gtc gaa gtc gcg ccg cgc gcg ggg gct ggc cga cgc tat ctg cga ttt ggt ctc tac cgg cgc gac gct tga | 26 | - | ND | + | ND | - |

| hisD6580 | aug acc agc ugc cgu caa aaa uau uga | 7 | - | - | - | ND | - |

| hisF6527 | ttg aaagaa agt ccg tga | 4 | - | - | - | ND | - |

| hisC3060 (−1 FS) | cgt gaa aat gtc cgc aac ctg gta ccg tat cag tct gcc cgc cgt ctΔg gcg gta acg gcg atg tct ggc tga | 22 | ND | ND | ND | - | - |

Frameshift windows are defined as the sequence between the first stop codon in the +1 frame and the stop codon in the new frame (italics). The base insertion is in boldface; the CCC or GGG frameshift sites are underlined. hisC3060 is a −1 frameshift mutation, and its frameshift window is accordingly between the first stop codon in the −1 frame and the stop codon in the zero frame. The sequences of hisB6480, hisD2780, hisD3040, hisF2439, hisF3704, hisD3068, hisG3037, hisD6580, hisF6527, and hisC3060 were determined in the present study. The sequences of hisD3018 (26), hisC3737 (4), hisD3749 (3), hisD6610 (26), and hisC3072 (25) were determined earlier. The frameshift suppressor sufA codes for altered  , the sufB codes for altered

, the sufB codes for altered  , the sufD codes for altered

, the sufD codes for altered  , and the sufF codes for altered

, and the sufF codes for altered  were published previously (22, 25, 34, 36, 39).

were published previously (22, 25, 34, 36, 39).

+ and (+), stronger or weaker growth observed after 3 days or earlier; -, no growth after 4 days; ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

Here we describe alterations in the ribosomal protein L9 that induce frameshifting to suppress a chromosomal +1 frameshift mutation in the hisC gene. Most of the alterations obtained were located in the C terminus of L9, and only one was in its N-terminal part. A break in the α-helix was introduced by changing an Ala-to-Pro change at position 59 within this helix, which also induced frameshifting, suggesting that the geometric relationship between the two globular domains is important for L9 to improve reading frame maintenance.

All mutants isolated here were required to synthesize a functional HisC protein for growth. This was possible only via shifts to the +1 frame during the translation of hisC3072 mRNA. However, among the His+ mutants it was not possible to differentiate whether the functional HisC protein was synthesized via +1 frameshifting to an overlapping codon or via bypassing to a downstream codon in the +1 reading frame. The efforts to identify the point of frameshift or bypassing by N-terminal sequencing of the frameshift product (Fig. 2) gave no clear answer. The requirement for long frameshift windows (Table 3), the synthesis of several frameshift products as revealed by a fuzzy band on the gel (Fig. 2), and no definitive sequence over the frameshift site is consistent with either a shift within overlapping codons at multiple places or bypassing from several take-off sites over many codons occurs producing different frameshift peptides. An increase in bypassing and the diversity of landing sites have been previously observed in L9-deficient ribosomes (17).

Protein L9 is part of the 50S ribosomal subunit and is a highly elongated protein consisting of two globular domains (N domain and C domain) separated by a connecting nine-turn α-helix. Each domain has conserved aromatic and positively charged amino acid residues on their surface, allowing them to bind to rRNA (18). The binding of the N domain was localized to domain V of 23S rRNA close to the base of the L1 stalk (27, 31, 38, 45). The L1 stalk is actively involved in the translocation movement of tRNA from the P site to the E site (32). The C domain and the connecting helix of L9 undergo significant movement during ribosomal cycling (10). The amino acids involved in RNA binding are clustered together in the N domain, whereas amino acids predicted to be involved in RNA binding in the C terminus are more scattered (18). Therefore, even though the changes in the C-terminal domain are close to the putative RNA-binding sites, there still may be enough sites left for interaction with the RNA and allow such altered L9 to assemble into the ribosome.

The functional aspect of L9 has been studied only by analyzing how its various alterations influence the translational bypassing of an mRNA encoded from a multicopy plasmid containing the bacteriophage T4 gene 60 site (15). Although the first mutant (S93F) isolated was a genomic mutant (14), all other characterized mutants were obtained after mutagenesis of the rplI gene located on a plasmid (1). Such an approach forces the mutant form to compete with the wild-type protein encoded by the chromosomal allele rplI+. Thus, to manifest a phenotype the mutant must be dominant. Here we have only isolated mutants with altered L9 encoded on the chromosome, which allows the detection of both dominant and recessive rplI mutations. Since L9 is not an essential protein, some mutant forms of L9 may not be incorporated into ribosomes and phenotypically would be equivalent to an rpsI deletion. The unbiased selection for frameshift suppressors in the rplI area on the chromosome allowed isolation of rplI mutants with unchanged gene expression levels and producing a homogeneous ribosome population containing only mutated or no protein L9. Hence, the approach taken in the present study is distinctly different from that used by Adamski et al. (1). Mutant analysis in the present study relied on the ability of the altered L9 to induce frameshifting on a chromosomally located +1 frameshift mutation (hisC3072), a very sensitive system to detect low levels of frameshifting.

Although the number of mutants is rather low, all (four amino acid substitutions and all frameshift mutations, see Fig. 1) except one resulted in an altered or deleted C-terminal globular domain. The exception is the mutant G24D (rplI2) in the N-terminal domain. This amino acid substitution is at the same position as the mutations G24A and G24P isolated earlier (1). Although the latter two alterations did not induce bypassing, purified L9 protein containing G24P bound poorly to a 23S rRNA fragment, which suggests that such altered L9 is not assembled into ribosomes. Since the absence of L9 induces bypassing, it seems likely that G24P is a recessive mutation allowing the wild-type L9 encoded from the chromosome to outcompete the mutant form in the ribosome assembly process resulting in a wild-type ribosome. The G24D-altered L9 isolated here induced frameshifting that could also depend on impaired rRNA binding, which hindered G24D-containing L9 to be incorporated into the ribosome. In addition, the N-terminal domain is also the dominating RNA-binding domain and, in fact, in the three-dimensional structure of the 70S ribosome the N domain is buried in the 50S subunit, and the α-helix and C domain are extended beyond the surface of the ribosome (45). All this together suggests that the discrepancy between the phenotypes induced by the various amino acid substitutions at position 24 of L9 is likely explained by the presence or absence of a wild-type form of L9.

Five isolated frameshift suppressors had frameshift mutations in the rplI gene (Fig. 1). One of them, rplI1, caused a truncation of L9, leaving only a small portion of the N-terminal domain, which was probably too small to be incorporated into the ribosome. Two other suppressors, rplI3 and rplI4, encoded a L9 protein with an intact N domain, but lacking the α-helix and the C domain. Mutation rplI5 omitted only the C domain of L9, while rplI10 mutation changed the extreme C terminus of L9 and extended it by 16 amino acids. It is possible that differently truncated forms of L9 with the intact N domain and with or without parts of the C domain, as in the rplI3, rplI4, rplI5, and rplI10 mutants, could be assembled into the ribosome. However, we cannot rule out that these frameshift mutations render L9 unable to bind to the ribosome and therefore act like a deletion of rplI.

Mutant L9 proteins isolated earlier were shown to be dominant, suggesting that they are assembled into the ribosome and stimulate bypassing (1). The amino acid substitutions in the C domain of L9, isolated here as inducing suppression of +1 frameshift mutations, are located close to already-described amino acid substitutions (1). Moreover, based on the fact that our and the earlier-described mutations alter the same area of L9, we assume that L9 harboring I94S, A102D, or F132S could also be assembled into the ribosome. The alteration at position 126 (G126V) mediated frameshifting (Table 2), although the G126W and G126V (i.e., the same alteration as ours) isolated earlier, did not induce bypassing (1). The explanation of this discrepancy is either the presence of dominating wild-type copy of L9 in the analysis of bypassing by Adamski et al. (1) or differences in sensitivity of the assays used. In conclusion, by using different systems we show that the alterations in the C-globular domain result in less restrictive reading frame maintenance, supporting the role of L9 in translational bypassing as seen in bacteriophage T4 gene 60-derived mRNA.

The length of the rigid connecting α-helix of L9, but not its amino acid sequence, is conserved. However, inserting four alanines or removing four amino acids of the α-helix does not increase bypassing, whereas altering the length by one or two alanines does (1). Such mutations alter the length of the α-helix and the relative positions of the globular domains. A four-amino-acid insertion or removal changes the alignment less than an insertion of one or two amino acids, suggesting that the geometric relationship between the two domains is important (1). The Ala-to-Pro substitution at position 65, as constructed by Adamski et al. (1), or at position 59, as constructed here, should both break the α-helix and misalign the globular domains. Whereas A65P does not induce bypassing (1), the A59P alteration induced weak frameshifting (Table 2). A suppression level induced by the A58P mutation lower than that observed in the mutants lacking L9 hints that the A59P mutant protein is incorporated into the ribosome but does not function to full extent. The difference in the A65P versus A59P mutant results could depend on the differences in the assay systems. The A65P-altered L9 was synthesized from a plasmid and, because the wild-type L9 was produced from the chromosome, the ribosome population was heterogeneous. On the other hand, the A59P protein was synthesized from the chromosome, and no other form of L9 was present; therefore, only the mutant form of ribosomes was assembled. Moreover, the assay monitoring frameshift suppression of the hisC3072 mutation is most likely more sensitive than the method used by Adamski et al. (1) (see Materials and Methods). We conclude that the geometric orientation of two globular domains is important to correctly position the C domain to the same ribosome (looping back) or, if the function of L9 is to act like a “strut,” to a neighboring ribosome on the mRNA.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Foundation (project 680) and the Swedish Science Research Council (project BU-2930).

We thank Gunilla Jäger, Kristina Nilsson, and Kerstin Jacobsson for technical assistance and Per-Ingvar Ohlsson at the Department of Plant Physiology, Umeå University, and the Protein Analysis Center at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Karolinska Institute, for protein sequencing. We also thank Norma M. Wills and John F. Atkins for providing the vector pGHM57; Dan Andersson, Uppsala, Sweden, for providing the plasmid pSMP24 before its publication; and John Roth, University of California at Davis, for the generous gift of numerous strains containing his mutations. We also thank John Atkins, Tord Hagervall, Joakim Näsvall, and Jaunius Urbonavičius for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamski, F. M., J. F. Atkins, and R. F. Gesteland. 1996. Ribosomal protein L9 interactions with 23 S rRNA: the use of a translational bypass assay to study the effect of amino acid substitutions. J. Mol. Biol. 261:357-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertani, G. 1951. Studies on lysogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 62:293-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bossi, L., and J. R. Roth. 1981. Four-base codons ACCA, ACCU and ACCC are recognized by frameshift suppressor sufJ. Cell 25:489-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, P., P. F. Crain, S. J. Näsvall, S. C. Pomerantz, and G. R. Björk. 2005. A “gain of function” mutation in a protein mediates production of novel modified nucleosides. EMBO J. 24:1842-1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis, W., D. Botstein, and J. R. Roth. 1980. A manual for genetic engineering: advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, NY.

- 7.Farabaugh, P. J. 1996. Programmed translational frameshifting. Annu. Rev. Genet. 30:507-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farabaugh, P. J. 1997. Programmed alternative reading of the genetic code: programmed alternative reading of the genetic code. R. G. Landes Company, Austin, TX.

- 9.Farabaugh, P. J., and G. R. Björk. 1999. How translational accuracy influences reading frame maintenance. EMBO J. 18:1427-1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao, H., J. Sengupta, M. Valle, A. Korostelev, N. Eswar, S. M. Stagg, P. Van Roey, R. K. Agrawal, S. C. Harvey, A. Sali, M. S. Chapman, and J. Frank. 2003. Study of the structural dynamics of the Escherichia coli 70S ribosome using real-space refinement. Cell 113:789-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gesteland, R. F., and J. F. Atkins. 1996. Recoding: dynamic reprogramming of translation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65:741-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greeb, J., J. F. Atkins, and J. C. Loper. 1971. Histidinol dehydrogenase (hisD) mutants of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 106:421-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen, T. M., P. V. Baranov, I. P. Ivanov, R. F. Gesteland, and J. F. Atkins. 2003. Maintenance of the correct open reading frame by the ribosome. EMBO Rep. 4:499-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herbst, K. L., L. M. Nichols, R. F. Gesteland, and R. B. Weiss. 1994. A mutation in ribosomal protein L9 affects ribosomal hopping during translation of gene 60 from bacteriophage T4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:12525-12529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herr, A. J., J. F. Atkins, and R. F. Gesteland. 2000. Coupling of open reading frames by translational bypassing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:343-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herr, A. J., C. C. Nelson, N. M. Wills, R. F. Gesteland, and J. F. Atkins. 2001. Analysis of the roles of tRNA structure, ribosomal protein L9, and the bacteriophage T4 gene 60 bypassing signals during ribosome slippage on mRNA. J. Mol. Biol. 309:1029-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herr, A. J., N. M. Wills, C. C. Nelson, R. F. Gesteland, and J. F. Atkins. 2004. Factors that influence selection of coding resumption sites in translational bypassing: minimal conventional peptidyl-tRNA:mRNA pairing can suffice. J. Biol. Chem. 279:11081-11087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffman, D. W., C. S. Cameron, C. Davies, S. W. White, and V. Ramakrishnan. 1996. Ribosomal protein L9: a structure determination by the combined use of X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 264:1058-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong, J. S., and B. N. Ames. 1971. Localized mutagenesis of any specific small region of the bacterial chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 68:3158-3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang, W. M., S. Z. Ao, S. Casjens, R. Orlandi, R. Zeikus, R. Weiss, D. Winge, and M. Fang. 1988. A persistent untranslated sequence within bacteriophage T4 DNA topoisomerase gene 60. Science 239:1005-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ino, I., P. E. Hartman, Z. Hartman, and J. Yourno. 1975. Deletions fusing the hisG and hisD genes in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriology 123:1254-1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohno, T., L. Bossi, and J. R. Roth. 1983. New suppressors of frameshift mutations in Salmonella typhimurium. Genetics 103:23-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korostelev, A., S. Trakhanov, M. Laurberg, and H. F. Noller. 2006. Crystal structure of a 70S ribosome-tRNA complex reveals functional interactions and rearrangements. Cell 126:1065-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurland, C. G., D. Hughes, and M. Ehrenberg. 1996. Limitations of translation accuracy, p. 979-1004. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 25.Leipuviene, R., and G. R. Björk. 2005. A reduced level of charged tRNAArgmnm5UCU triggers the wild-type peptidyl-tRNA to frameshift. RNA 11:796-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levin, D. E., E. Yamasaki, and B. N. Ames. 1982. A new Salmonella tester strain, TA97, for the detection of frameshift mutagens: a run of cytosines as a mutational hot-spot. Mutat. Res. 94:315-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lieberman, K. R., M. A. Firpo, A. J. Herr, T. Nguyenle, J. F. Atkins, R. F. Gesteland, and H. F. Noller. 2000. The 23 S rRNA environment of ribosomal protein L9 in the 50 S ribosomal subunit. J. Mol. Biol. 297:1129-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohkamp, B., G. McDermott, S. A. Campbell, J. R. Coggins, and A. J. Lapthorn. 2004. The structure of Escherichia coli ATP-phosphoribosyltransferase: identification of substrate binding sites and mode of AMP inhibition. J. Mol. Biol. 336:131-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maisnier-Patin, S., J. R. Roth, A. Fredriksson, T. Nyström, O. G. Berg, and D. I. Andersson. 2005. Genomic buffering mitigates the effects of deleterious mutations in bacteria. Nat. Genet. 37:1376-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maloy, S. R., and W. D. Nunn. 1981. Selection for loss of tetracycline resistance by Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 145:1110-1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matadeen, R., A. Patwardhan, B. Gowen, E. V. Orlova, T. Pape, M. Cuff, F. Mueller, R. Brimacombe, and M. van Heel. 1999. The Escherichia coli large ribosomal subunit at 7.5 Å resolution. Struct. Folding Design 7:1575-1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noller, H. F., M. M. Yusupov, G. Z. Yusupova, A. Baucom, and J. H. Cate. 2002. Translocation of tRNA during protein synthesis. FEBS Lett. 514:11-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramakrishnan, V. 2002. Ribosome structure and the mechanism of translation. Cell 108:557-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riddle, D. L., and J. Carbon. 1973. Frameshift suppression: a nucleotide addition in the anticodon of a glycine transfer RNA. Nat. New Biol. 242:230-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riddle, D. L., and J. R. Roth. 1970. Suppressors of frameshift mutations in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol. 54:131-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riddle, D. L., and J. R. Roth. 1972. Frameshift suppressors. II. Genetic mapping and dominance studies. J. Mol. Biol. 66:483-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmieger, H. 1972. Phage P22-mutants with increased or decreased transduction abilities. Mol. Gen. Genet. 119:75-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuwirth, B. S., M. A. Borovinskaya, C. W. Hau, W. Zhang, A. Vila-Sanjurjo, J. M. Holton, and J. H. Cate. 2005. Structures of the bacterial ribosome at 3.5 Å resolution. Science 310:827-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sroga, G. E., F. Nemoto, Y. Kuchino, and G. R. Björk. 1992. Insertion (sufB) in the anticodon loop or base substitution (sufC) in the anticodon stem of tRNAProI2 from Salmonella typhimurium induces suppression of frameshift mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:3463-3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teng, H., and C. Grubmeyer. 1999. Mutagenesis of histidinol dehydrogenase reveals roles for conserved histidine residues. Biochemistry 38:7363-7371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vogel, H. J., and D. M. Bonner. 1956. Acetylornithinase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J. Biol. Chem. 218:97-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wagner, J., P. Gruz, S. R. Kim, M. Yamada, K. Matsui, R. P. Fuchs, and T. Nohmi. 1999. The dinB gene encodes a novel Escherichia coli DNA polymerase, DNA pol IV, involved in mutagenesis. Mol. Cell 4:281-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagner, J., and T. Nohmi. 2000. Escherichia coli DNA polymerase IV mutator activity: genetic requirements and mutational specificity. J. Bacteriol. 182:4587-4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yourno, J., and S. Tanemura. 1970. Restoration of in-phase translation by an unlinked suppressor of a frameshift mutation in Salmonella typhimurium. Nature 225:422-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yusupov, M. M., G. Z. Yusupova, A. Baucom, K. Lieberman, T. N. Earnest, J. H. Cate, and H. F. Noller. 2001. Crystal structure of the ribosome at 5.5 Å resolution. Science 292:883-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]