Abstract

An in vitro model of supragingival plaque associated with gingivitis was characterized by traditional culture techniques, comparative 16S rRNA gene sequencing of isolates, and quantitative PCR (QPCR). Actinomyces naeslundii, Prevotella spp., and Porphyromonas gingivalis increased under conditions emulating gingivitis. Gram-negative species and total bacteria were dramatically underestimated by culture compared to the estimates obtained by QPCR.

Inadequate oral hygiene leads to dental plaque accumulation around the gingival margin, resulting in inflammation of the gingiva. The environmental changes which occur as a result drive the ecological changes in the oral microbiota at this site, such as the ascendancy of Actinomyces spp. and gram-negative rods at the expense of Streptococcus spp. (19, 20, 26, 31). With the advance of molecular techniques such as cloning and sequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene, a greater proportion of species present in the oral cavity than the proportion that can be detected by traditional culture techniques has been detected, and the number of bacterial species present in the dental plaque is now estimated to be upwards of 630 (8). Quantitative PCR (QPCR) has the potential to account for the uncultivable portion of the oral microbial community as well as species which are more difficult to culture, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis (14, 22), Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (formerly Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans) (3), and oral treponemes (2).

Using the constant-depth film fermentor (CDFF) model for oral biofilms, we have previously demonstrated reproducible population shifts in the microbial community associated with gingivitis by altering the environmental conditions (4). The aim of this study was to identify the range of cultivable species present in this in vitro system and to monitor changes in specific species and genera as a response to changing environmental conditions by QPCR.

Dental plaque biofilms associated with health and gingivitis were produced in the CDFF, removed aseptically at various time points, and analyzed by selective cultural analysis by using methods described previously (4). Total anaerobic counts were obtained on fastidious anaerobe agar (FAA; Bioconnections, Leeds, United Kingdom), Actinomyces spp. were selected for on cadmium fluoride acriflavine tellurite plates (CFAT) (32), Streptococcus spp. were selected for on mitis-salivarius agar (MS; BD Biosciences, Oxford, United Kingdom), and gram-negative species were selected for on Columbia blood agar with a supplement for gram-negative organisms (GN; Oxoid).

The identification of cultivable species was carried out by comparative 16S rRNA gene sequencing. At various sampling time points, all the different colony morphotypes were subcultured on selective media (MS, CFAT, and GN) and 15 random isolates were subcultured from the nonselective media (FAA and Columbia blood agar) for identification. The primers used for 16S rRNA PCR are described in Table 1 and were used under the conditions described previously (23) to amplify and partially sequence the 16S rRNA region. The sequences generated (up to 500 bases) were checked by using the CHROMAS program (version 1.43) and were then compared with the 16S rRNA gene sequences deposited in the database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (1) by use of the BLAST program to find sequences with the closest match.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Species or primer type | Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Length (bp) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevotella spp. | Forward | CCAGCCAAGTAGCGTGCA | 20 | 16 |

| Reverse | TGGACCTTCCGTATTACCGC | 18 | 16 | |

| Fusobacterium spp. | Forward | AAGCGCGTCTAGGTGGTTATGT | 22 | 16 |

| Reverse | TGTAGTTCCGCTTACCTCTCCAG | 23 | 16 | |

| Streptococcus spp. | Forward | AGATGGACCTGCGTTGT | 17 | 25 |

| Reverse | GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGTCT | 20 | 25 | |

| P. gingivalis | Forward | CTTGACTTCAGTGGCGGCAG | 20 | 15 |

| Reverse | AGGGAAGACGGTTTTCACCA | 20 | 15 | |

| A. naeslundii | Forward | CTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG | 19 | 10 |

| Reverse | CACCCACAAACGAGGCAG | 18 | 29 | |

| Universal (multiple species) | Forward | TCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGT | 19 | 16 |

| Reverse | GGACTACCAGGGTATCTAATCCTGTT | 26 | 16 | |

| 16S rRNA gene sequencing primers | ||||

| 27F | Forward | AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG | 20 | 10 |

| 357F | Forward | CTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG | 19 | 10 |

| 1492R | Reverse | TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT | 22 | 10 |

The specificities of the QPCR primers were tested by using Actinomyces naeslundii NCTC 10301; Actinomyces viscosus NCTC 10951; Actinomyces odontolyticus NCTC 9935; Actinomyces israelii NCTC 10236; Streptococcus sanguinis NCTC 7863; Streptococcus parasanguinis NCTC 55898; Streptococcus sobrinus NCTC 12279; Streptococcus gordonii NCTC 7865; Streptococcus oralis NCTC 11427; Streptococcus cristatus CR311; Streptococcus mutans NCTC 10499; Streptococcus salivarius NCTC 8618; Streptococcus anginosus NCTC 10713; Streptococcus mitis NCTC 12261; and oral isolates of Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Enterococcus faecalis, Gemella haemolysans, Citrobacter youngae, Abiotrophia defectiva, and Rothia dentocariosa. To obtain CFU counts for these bacteria to produce standard curves for the QPCR, cultures were grown in brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid) at 37°C under anaerobic conditions for 3 to 4 days. DNA was extracted from biofilms obtained at selected time points from 500 μl of bacterial culture by using the Puregene DNA isolation kit for yeast and gram-positive bacteria (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The primers used for this study are listed in Table 1. The primers were all checked for their specificities against the panel of oral species listed and were found to be specific for their intended targets. Extracted DNA corresponding to known numbers of bacterial cells was serial diluted and used to create standard curves (six 10-fold dilutions were used). For the universal primers, serial dilutions of a number of different species were used (due to the different gene copy numbers in different species). QPCR was performed with an ABI PRISM 7300 sequence detection system (PE Applied Biosystems). The reaction mixture (25 μl) contained 2× POWER SYBR green universal PCR master mixture (PE Applied Biosystems), 20 pmol of forward and reverse primers (Sigma-Genosys), and 2.5 μl of extracted DNA. The thermocycling program was 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min, with an initial cycle of 95°C for 10 min. All amplifications and detections were carried out in a MicroAmp optical 96-well reaction plate with optical caps (PE Applied Biosystems). At each cycle, the accumulation of PCR products was detected by monitoring the increase in fluorescence of the reporter dye, double-stranded DNA-binding SYBR green. After the PCR, a dissociation curve (melting curve) was constructed in the range of 60°C to 95°C. All data were analyzed by using ABI PRISM 7300 SDS software.

By identifying the cultivable flora by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, it was observed that a greater number of species from a wider range of genera were identified after changing the environmental conditions to emulate the conditions that occur during gingivitis (Table 2). A total of 16 taxa (3 from saliva, 2 from conditions emulating health, and 12 under conditions emulating gingivitis) were detected uniquely in only one of the sample types (Table 2). The 16 taxa were identified under conditions emulating health, with streptococci representing ca. 44% of the taxa and Actinomyces spp. representing ca. 6% of the taxa. In contrast, under conditions emulating gingivitis, 29 taxa were identified, with streptococci representing ca. 28% of all species detected and Actinomyces spp. representing ca. 21% of all species detected. A. odontolyticus was the only Actinomyces spp. identified under conditions emulating health. In contrast, A. naeslundii, A. viscosus, Actinomyces suimastitidis, and Actinomyces turicensis were identified under conditions emulating gingivitis (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Cultivable taxa identified by 16S rRNA sequencing from saliva and plaque samples grown under conditions emulating health and gingivitis

| Species | Species present under conditions emulatinga:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Saliva | Health | Gingivitis | |

| Citrobacter sp. genomospecies 11 | + | ||

| Citrobacter youngae | + | ||

| Veillonella dispar | + | ||

| Veillonella parvula | + | + | + |

| Brevibacillus agri | + | ||

| Gemella hemolysans | + | ||

| Gemella sanguinis | + | ||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis/Staphylococcus caprae | + | ||

| Abiotrophia defectiva | + | ||

| Abiotrophia paraadiacens | + | + | |

| Granulicatella adiacens | + | + | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | + | + | |

| Enterococcus sp. strain 8 | + | + | |

| Lactobacillus casei/Lactobacillus paracasei | + | ||

| Lactobacillus fermentum/Lactobacillus cellobiosus | + | ||

| Lactobacillus fermentum | + | + | |

| Streptococcus anginosus | + | ||

| Streptococcus genomospecies C8 | + | + | |

| Streptococcus gordonii/Streptococcus mitis | + | + | |

| Streptococcus mitis group | + | + | |

| Streptococcus mitis | + | + | |

| Streptococcus oralis/Streptococcus mitis | + | + | |

| Streptococcus parasanguinis | + | ||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | + | ||

| Streptococcus salivarius | + | + | |

| Streptococcus sanguinis | + | + | + |

| Streptococcus suis | + | ||

| Actinomyces graevenitzii | + | ||

| Actinomyces lingnae | + | + | |

| Actinomyces naeslundii | + | + | |

| Actinomyces odontolyticus | + | + | |

| Actinomyces viscosus | + | + | |

| Actinomyces suimastitidis | + | ||

| Actinomyces turicensis | + | ||

| Rothia dentocariosa | + | + | + |

| Prevotella veroralis | + | + | |

| Total no. of isolates | 13 | 16 | 29 |

| No. of unique isolates | 3 | 2 | 12 |

Boldface represents species unique to that sampling point.

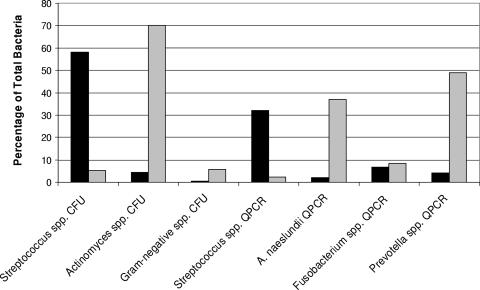

The Streptococcus sp. estimates by QPCR were higher than those obtained on selective media (Table 3). Under conditions emulating health, Streptococcus spp. represented ca. 32% of the total bacteria detected, while A. naeslundii accounted for only ca. 2% (Fig. 1). In contrast, once the conditions were altered to emulate gingivitis, Streptococcus spp. represented only ca. 2% of the total bacteria, while A. naeslundii accounted for ca. 37% (Fig. 1). Prevotella spp. represented ca. 4% of the total bacteria under conditions emulating health (Table 3) and then increased dramatically under conditions emulating gingivitis to account for ca. 49% (Table 3) of the total bacteria detected. Fusobacterium sp. levels remained stable and represented ca. 6% of the total bacteria under conditions emulating health and ca. 8% of the total bacteria under conditions emulating gingivitis (Fig. 1). P. gingivalis was detected at very low levels from microcosm plaque samples (Table 3), with the numbers increasing under conditions emulating gingivitis, but it still represented a very small portion (less than c0.1%) of the total bacteria detected.

TABLE 3.

Bacterial counts estimated as numbers of CFU and by QPCR under conditions emulating health and gingivitis

| Species | Technique | Total counts under conditions emulatinga:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Gingivitis | ||

| Actinomyces spp. | CFU | 4.48 (±1.15) × 106 | 6.25 (±0.88) × 108 |

| Actinomyces naeslundii | QPCR | 3.86 (±0.81) × 106 | 3.33 (±0.85) × 108 |

| Streptococcus spp. | CFU | 9.76 (±2.26) × 107 | 2.20 (±0.65) × 106 |

| Streptococcus spp. | QPCR | 4.84 (±0.99) × 108 | 6.09 (±1.60) × 106 |

| Gram-negative species | CFU | 2.22 (±0.88) × 106 | 2.00 (±0.19) × 107 |

| Prevotella spp. | QPCR | 3.09 (±0.23) × 107 | 4.93 (±3.28) × 108 |

| Fusobacterium spp. | QPCR | 5.06 (±0.78) × 107 | 5.52 (±0.19) × 107 |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | QPCR | 1.71 (±1.41) × 103 | 1.90 (±1.29) × 104 |

Data are means (± standard deviations) (n = 4).

FIG. 1.

Different species/genera represented as a percentage of the total number of bacteria by culture and QPCR. Solid bars, percentages in biofilms grown under conditions emulating health; shaded bars, percentages in biofilms grown under conditions emulating gingivitis.

Microcosm plaques grown in the CDFF model have been characterized previously by direct amplification and cloning of 16S rRNA genes (23). Only five species that were not detected by culture were detected by cloning, including Prevotella spp. and F. nucleatum, indicating that most species grown in this model could be detected by culture or that more species could not be detected due to the inherent biases of cloning techniques. Similarly, by using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis to create genetic fingerprints of microcosm communities developed in the CDFF model (17), it was shown that few dominant bands were present, which corresponds to a low diversity of species. Therefore, for this study, to characterize the changes in the communities associated with environmental conditions emulating health and gingivitis, a combination of culture and QPCR for specific species was chosen.

The most significant observation from this study is that the results of QPCR confirm the trends observed by culture in a previous study (4), in that the number of Actinomyces spp. (A. naeslundii in particular) increased as the number of Streptococcus spp. decreased when the medium and atmospheric conditions were altered. While fewer Streptococcus species were identified by sequencing under conditions emulating gingivitis, S. anginosus and Streptococcus pneumoniae were both detected under these conditions but not under those emulating health. Interestingly, from experimental gingivitis studies, the presence of S. anginosus has been shown to have a positive correlation with gingivitis (18). A greater richness of Actinomyces spp. was identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing under conditions emulating gingivitis, including A. naeslundii and A. viscosus, which are associated with gingivitis (19, 20, 26, 31). The increased species richness under conditions emulating gingivitis involved the emergence of species not typical of the oral cavity, such as Citrobacter spp., which have been isolated from other models of supragingival plaque (17).

Prevotella spp. are more commonly isolated from dental plaque after the development of periodontal diseases (12, 30). Serum is a constituent of gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) and has been shown to enhance the growth of Prevotella spp. and P. gingivalis (27). Prevotella spp. accounted for a large portion of the microbial community after the induction of gingivitis conditions but were rarely isolated by culture techniques. Martin et al. (16) detected counts for Prevotella spp. by QPCR, using the same primers used in this study, significantly higher than the counts that they detected using selective culture techniques. Fusobacterium spp. did not really increase under conditions emulating gingivitis, even though these organisms are often linked to periodontal disease. This may be due to the presence of Fusobacterium spp. lacking the endopeptidase activity required to break down the large proteinaceous nutrients present in GCF. F. nucleatum possesses aminopeptidase activity (24) and can thus utilize protein-derived nutrients (e.g., amino acids and oligonucleotide peptides) by linking to proteolytic organisms such as P. gingivalis (9). P. gingivalis was detected in the pooled saliva and the inoculum but did not form a significant part of the microcosm communities. The numbers did increase 10-fold under conditions emulating gingivitis but still represented a very small proportion of the community. Supragingival plaque communities associated with health do not usually contain high numbers of P. gingivalis (11), which tend to be more significant members of the subgingival plaque community (28).

Over time, the total bacterial numbers remained in a pseudo-steady state. Any fluxes in the populations appeared to be related to the proportions of species rather than the total bacterial numbers. The mean estimates of the total bacterial counts calculated by QPCR with universal primers was 6.8 × 108 (±1.4 × 108) bacteria per biofilm, whereas by colony counting the mean count was significantly less at 1.4 × 108 (±3.4 × 107) CFU per biofilm, which represented, on average, only 20% of the microbial population estimated by QPCR. This may be due to the detection of uncultivable species by QPCR (21) and possibly due to the fact that cells were in a viable but nonculturable state (13) or the clumping of the bacteria into aggregates which are difficult to disrupt. Additionally, within the nutrient-limited biofilm environment, organisms with slower growth rates may have an advantage over faster-growing organisms, such as increased resistance to antibiotics (5). Previous studies that used QPCR to quantify total bacterial numbers in plaque samples have also observed total bacterial counts that were significantly lower by culture than by QPCR (16, 21). When the total bacteria are quantified by using universal primers based on the 16S rRNA gene, the total rRNA present in the sample is being quantified (7). The rRNA copy number is not uniform for all bacteria and varies between 1 and 15 copies per cell for different species (6, 7, 21), and it is therefore possible that this could account for some of the shortfall between the total estimates obtained by culture and those obtained by QPCR. An attempt to minimize this was made by using DNA extracted from a variety of oral species to create the standard curves for the calculation of total bacterial numbers.

The ultimate aim of the use of this in vitro model for the dental plaque associated with gingivitis is to test antimicrobial agents for their efficacies against the buildup of supragingival plaque. The use of QPCR to assess the species and genus numbers in these populations would allow the effects of these agents on particular organisms to be assessed more accurately than they can be by cultural analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the EPSRC. F.D. was the recipient of an EPSRC CASE studentship award supported by Proctor and Gamble.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asai, Y., T. Jinno, H. Igarashi, Y. Ohyama, and T. Ogawa. 2002. Detection and quantification of oral treponemes in subgingival plaque by real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3334-3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boutaga, K., P. H. Savelkoul, E. G. Winkel, and A. J. van Winkelhoff. 2007. Comparison of subgingival bacterial sampling with oral lavage for detection and quantification of periodontal pathogens by real-time polymerase chain reaction. J. Periodontol. 78:79-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalwai, F., D. A. Spratt, and J. Pratten. 2006. Modeling shifts in microbial populations associated with health or disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3678-3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans, D. J., D. G. Allison, M. R. Brown, and P. Gilbert. 1990. Effect of growth-rate on resistance of gram-negative biofilms to cetrimide. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 26:473-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrelly, V., F. A. Rainey, and E. Stackebrandt. 1995. Effect of genome size and rrn gene copy number on PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes from a mixture of bacterial species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2798-2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horz, H. P., M. E. Vianna, B. P. Gomes, and G. Conrads. 2005. Evaluation of universal probes and primer sets for assessing total bacterial load in clinical samples: general implications and practical use in endodontic antimicrobial therapy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5332-5337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kazor, C. E., P. M. Mitchell, A. M. Lee, L. N. Stokes, W. J. Loesche, F. E. Dewhirst, and B. J. Paster. 2003. Diversity of bacterial populations on the tongue dorsa of patients with halitosis and healthy patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:558-563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolenbrander, P. E., R. N. Andersen, D. S. Blehert, P. G. Egland, J. S. Foster, and R. J. Palmer, Jr. 2002. Communication among oral bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:486-505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lane, D. J. 1991. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing, p. 115-175. In M. G. E. Stackebrandt (ed.), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Academic Press, Chichester, England.

- 11.Lau, L., M. Sanz, D. Herrera, J. M. Morillo, C. Martin, and A. Silva. 2004. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction versus culture: a comparison between two methods for the detection and quantification of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tannerella forsythensis in subgingival plaque samples. J. Clin. Periodontol. 31:1061-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lie, M. A., G. A. van der Weijden, M. F. Timmerman, B. G. Loos, T. J. van Steenbergen, and U. van der Velden. 2001. Occurrence of Prevotella intermedia and Prevotella nigrescens in relation to gingivitis and gingival health. J. Clin. Periodontol. 28:189-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lleo, M. M., M. C. Tafi, and P. Canepari. 1998. Nonculturable Enterococcus faecalis cells are metabolically active and capable of resuming active growth. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21:333-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyons, S. R., A. L. Griffen, and E. J. Leys. 2000. Quantitative real-time PCR for Porphyromonas gingivalis and total bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2362-2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maeda, H., C. Fujimoto, Y. Haruki, T. Maeda, S. Kokeguchi, M. Petelin, H. Arai, I. Tanimoto, F. Nishimura, and S. Takashiba. 2003. Quantitative real-time PCR using TaqMan and SYBR Green for Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, tetQ gene and total bacteria. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 39:81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin, F. E., M. A. Nadkarni, N. A. Jacques, and N. Hunter. 2002. Quantitative microbiological study of human carious dentine by culture and real-time PCR: association of anaerobes with histopathological changes in chronic pulpitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1698-1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McBain, A. J., R. G. Bartolo, C. E. Catrenich, D. Charbonneau, R. G. Ledder, and P. Gilbert. 2003. Growth and molecular characterization of dental plaque microcosms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94:655-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore, L. V., W. E. Moore, E. P. Cato, R. M. Smibert, J. A. Burmeister, A. M. Best, and R. R. Ranney. 1987. Bacteriology of human gingivitis. J. Dent. Res. 66:989-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore, W. E., L. V. Holdeman, R. M. Smibert, I. J. Good, J. A. Burmeister, K. G. Palcanis, and R. R. Ranney. 1982. Bacteriology of experimental gingivitis in young adult humans. Infect. Immun. 38:651-667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore, W. E., and L. V. Moore. 1994. The bacteria of periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000 5:66-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nadkarni, M. A., F. E. Martin, N. A. Jacques, and N. Hunter. 2002. Determination of bacterial load by real-time PCR using a broad-range (universal) probe and primers set. Microbiology 148:257-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nonnenmacher, C., A. Dalpke, R. Mutters, and K. Heeg. 2004. Quantitative detection of periodontopathogens by real-time PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods 59:117-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pratten, J., M. Wilson, and D. A. Spratt. 2003. Characterization of in vitro oral bacterial biofilms by traditional and molecular methods. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 18:45-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers, A. H., A. Gunadi, N. J. Gully, and P. S. Zilm. 1998. An aminopeptidase nutritionally important to Fusobacterium nucleatum. Microbiology 144:1807-1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudney, J. D., Y. Pan, and R. Chen. 2003. Streptococcal diversity in oral biofilms with respect to salivary function. Arch. Oral Biol. 48:475-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Syed, S. A., and W. J. Loesche. 1978. Bacteriology of human experimental gingivitis: effect of plaque age. Infect. Immun. 21:821-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ter Steeg, P. F., J. S. Van der Hoeven, M. H. de Jong, P. J. van Munster, and M. J. Jansen. 1987. Enrichment of subgingival microflora on human serum leading to accumulation of Bacteroides species, Peptostreptococci and Fusobacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 53:261-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Winkelhoff, A. J., B. G. Loos, W. A. van der Reijden, and U. van der Velden. 2002. Porphyromonas gingivalis, Bacteroides forsythus and other putative periodontal pathogens in subjects with and without periodontal destruction. J. Clin. Periodontol. 29:1023-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia, T., and J. C. Baumgartner. 2003. Occurrence of Actinomyces in infections of endodontic origin. J. Endodont. 29:549-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ximenez-Fyvie, L. A., A. D. Haffajee, and S. S. Socransky. 2000. Microbial composition of supra- and subgingival plaque in subjects with adult periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 27:722-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zee, K. Y., L. P. Samaranayake, and R. Attstrom. 1996. Predominant cultivable supragingival plaque in Chinese “rapid” and “slow” plaque formers. J. Clin. Periodontol. 23:1025-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zylber, L. J., and H. V. Jordan. 1982. Development of a selective medium for detection and enumeration of Actinomyces viscosus and Actinomyces naeslundii in dental plaque. J. Clin. Microbiol. 15:253-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]