Abstract

Most studies of opportunistic infections focus on those with weak immune systems, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS patients and children. However, there is a lack of information on these infectious agents in healthy people worldwide. In the present study, stool samples from both HIV patients and healthy people were examined to begin filling in this serious gap in the understanding of human microsporidiosis, particularly the enteric parasite Enterocytozoon bieneusi. Specimens were obtained from 191 individuals living in Yaoundé, the capital city of Cameroon, in sub-Sahara Africa, including 28 HIV-positive patients who also had tuberculosis (TB). E. bieneusi prevalence was 35.7% among the HIV+ TB patients, whereas it was only 24.0% among 25 HIV− TB patients in the same hospital. Unexpectedly, the prevalence (67.5%) of microsporidiosis was found to be even higher for 126 immunocompetent individuals than for those with TB (healthy people compared to HIV+ TB and HIV− TB patients; P < 0.001). The immunocompetent group included people ranging from 2 to 70 years of age living in four different neighborhoods in Yaoundé. The highest prevalence (81.5%) was among teenagers, and the highest mean infection score (+2.5) was among children. Additional studies of immunocompetent people in other parts of Cameroon, as well as in other countries, are needed to better understand microsporidiosis epidemiology. There is still much more to be learned about the natural history of microsporidia, the pathogenicity of different strains, and the role of enteric microsporidia as opportunistic infections in immunodeficient people.

The sub-Saharan country of Cameroon, with a population exceeding 16 million, has one of the highest prevalence rates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the world; approximately 1 million adults (5.5%) are HIV positive (18a). The highest infection rate of HIV type 2 (HIV-2) and the most unusual HIV-1 subtypes in the world are found in this country. Furthermore, it is suspected that the virus was initially transmitted from chimpanzees to humans in Cameroon, where the emergence of the AIDS pandemic occurred (15). Therefore, the examination of natives of this country is of particular interest with respect to the epidemiology of opportunistic infections.

Cameroon is in western Africa. Its climate along the Atlantic seacoast is tropical, and it is semiarid and hot in the northern regions of the country. Mount Cameroon is the highest mountain in sub-Saharan western Africa. It is an active volcano, and thermal springs and other features of volcanic activity are found throughout the country. Besides HIV/AIDS, tropical diseases that are endemic to the area, such as malaria, sleeping sickness, and filariasis, also significantly weaken the immune system of its peoples, making them susceptible to infections by opportunistic pathogens.

Microsporidia have emerged as causative agents of opportunistic infections in AIDS patients and other immunodeficient individuals. Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis are the most common microsporidial parasites infecting humans, and they are associated with diarrhea and systemic disease. These microbes are very small (1 to 2 μm), single-celled obligate intracellular parasites characterized by a polar filament that is extruded during invasion of the host cell (11, 26). Mature microsporidian spores have thick three-layered walls, can pass through some water treatment filters due to their small size, and are resistant to chlorine at concentrations used in treating drinking water. Microsporidian spores have been found in drinking water sources, soil, and domestic and wild animals, suggesting the possibility of waterborne, food-borne, zoonotic, and anthroponotic transmission.

Two reports have been published regarding microsporidian spores in fecal samples taken from HIV+ patients in Cameroon (19, 21). However, data are lacking on the epidemiology of microsporidian infections in the general populace of Cameroon. This study was conducted to evaluate a broader representation of the people living in this country.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fecal specimens.

Freshly collected stool samples (2 to 3 g) were obtained from people in Yaoundé, Cameroon, between August and September 2003. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Cincinnati. In Cameroon, institutional review board approval is not required for obtaining specimens by noninvasive procedures. Specimens were obtained from patients at the Jamot Tuberculosis Hospital in Yaoundé, some of whom were coinfected with HIV. A no-conflict-of-interest letter was approved by a hospital authority, and he made his patients available for sample collection. Healthy individuals residing in four middle- to low-income urban neighborhoods volunteered and provided stool samples. Persons with symptoms of illness were not included in statistical analyses involving this group. The neighborhoods were Nlongkak, Biyem-Assi, Quartier General, and Bonamoussadi. Only a few households in Yaoundé have treated and chlorinated tap water piped directly into their homes, which is then sold to neighbors. To save on their water bills, it is a common practice for people in these neighborhoods to use water from wells available in each neighborhood for bathing, laundry, and cleaning of household utensils.

To obtain samples from hospitalized patients and the volunteers living in these four urban neighborhoods, clean glass cups were provided, and the specimens were collected between 5:30 and 8:00 a.m. the following morning. Specimens (30 to 50 g) were kept in a thermal flask containing ice blocks and were taken to the laboratory at the University of Yaoundé within 2 to 3 h. Specimens (2 to 3 g) were homogenized with 15 ml of a phosphate-buffered 10% formalin solution and allowed to stand at room temperature for 30 min (18). The fixed samples were passed through nylon sieves with 100-μm-diameter pores (Marathon Laboratories, London, United Kingdom) and collected into 15-ml polypropylene tubes, and aliquots of 2 to 3 ml were transferred into 5-ml tubes for storage until being shipped to Cincinnati, OH, for analysis. The remaining fixed and sieved specimens were subjected to ethyl acetate concentration (16), and the pellets (∼1 ml) were stored at room temperature until being shipped.

Calcofluor white staining.

Microscopic analysis of the stool samples was performed at the Tulane National Primate Research Center, Covington, LA (8, 9). Ten microliters of each specimen was smeared onto imprinted circular 10-mm2 areas on glass slides. Smears were allowed to dry and then were fixed in methanol for 10 min at room temperature. Specimens then were stained with calcofluor white and counterstained with Evan's blue. After being dried, the slides were stored in the dark until being read with a light microscope with epifluorescence optics. Organisms appear as turquoise ovals and were identified by characteristics that distinguish microsporidian spores from other organisms. These include size, a distinctly bluish turquoise color (compared to the greenish or yellowish turquoise observed in yeasts), and the various intensities of the staining (due to various stages of sporogony). Yeasts stain with consistent intensity; bacterial spores also may stain with calcofluor, but they are much smaller.

Slides were viewed at a ×600 magnification under oil. Microsporidian concentrations were quantified by the following scoring system: 0, <5 spores in ≥20 microscopic fields; +1, <1 spore/field but ≥5 total spores observed; +2, 1 to 5 spores/field; +3, 6 to 10 spores/field; +4, >10 spores/field. Mean infection scores for different study groups were calculated by the sum of the number of cases with a given score multiplied by the infection score, divided by the number of infected people in that study group {[Σ (infection score × number of specimens)]/number infected}.

Clusters of 10 or more closely grouped microsporidia were observed. These organisms exhibited differing staining intensities, reflecting the different stages of sporogony (i.e., different levels of chitin expression in the spore wall), which is diagnostic for microsporidia.

IFA.

Initial indirect immunofluorescence analysis (IFA) was performed on randomly selected stool specimens from each infection score category to verify the identification of microsporidian spores in these stool samples. The infection score categories (number of samples analyzed by IFA) were as follows: 0 (3), +1 (2), +2 (2), +3 (3), and +4 (5). Two different immunoglobulin G (IgG) monoclonal antibody (MAb) preparations were obtained from Bordier Affinity Products SA (Crissier, Switzerland) as primary antibodies. One was directed against Enterocytozoon bieneusi spores, and the other was directed against Encephalitozoon intestinalis spores (1). A third MAb preparation was generously provided by Saul Tzipori (Tufts University, Grafton, MA). This was an IgM MAb preparation directed against Enterocytozoon bieneusi spores (27).

An aliquot (2 μl) of each fecal sample was placed in the well of a multiple-well IFA glass slide or was added inside a circumscribed area (7-mm diameter) on a regular flat microscope slide by using a wax pencil. Each specimen was air dried, heat fixed, and treated with acetone for 10 min at −20°C. A drop of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) was added, and after 5 min the liquid was removed with a filter paper. Undiluted MAb (20 μl) was added, and the preparation was incubated in a humid chamber for 30 min at room temperature. After incubation, the slides were washed in PBS and then incubated in the dark with 20 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (U.S. Biologicals, Swampscott, MA) diluted 1:500 in PBS containing Evan's blue (5 μg/ml) as a counterstain. After 30 min of incubation, the slides were washed in three changes of PBS, mounted, and examined with a Nikon Optiphot microscope equipped with epifluorescence illumination and a Uvitex 2B filter. Micrographs were obtained by a Spot II camera (Diagnostics Instruments, Inc., Sterling Heights, MI) at a ×1,000 magnification.

Encephalitozoon intestinalis microsporidia were grown with RK-13 rabbit kidney epithelium cultures (10), and spores were isolated from culture supernatants by centrifugation and washing. Formalin-fixed spores were used as positive controls for identifying this organism in stool samples.

Data analysis.

The presence of spores and infection scores were recorded for specimens and analyzed according to gender, medical history, neighborhood, and household. People also were grouped according to age in years: infants (0 to 5), children (6 to 11), teenagers (12 to 19), adults (20 to 50), and elderly (≥50). Comparisons between various groups were subjected to chi-square and Student t test analyses.

RESULTS

Prevalence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in people in Yaoundé, Cameroon.

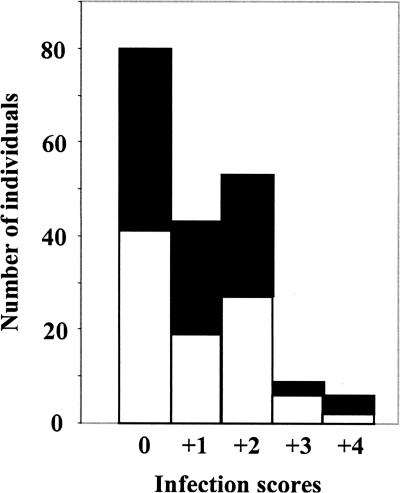

The entire group of 191 individuals in the present study included healthy individuals as well as patients with tuberculosis (TB), HIV, and other infections. The overall prevalence of microsporidian infections was 58.1%. The prevalence among the 95 females examined was 56.8%, and that among the 96 males analyzed was 59.4% (Fig. 1); hence, there was no gender difference.

FIG. 1.

Microsporidiosis infection scores of total fecal samples analyzed in this study. White bars, females; black bars, males.

Symptoms of diarrhea and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in stool.

Of the 191 samples analyzed, only 13 came from individuals with diarrhea (frequent excretion of watery stool). Microsporidian spores were detected in 7 of the 13 cases, and four and three individuals had parasite load scores of only +1 and +2, respectively. Hence, there was no apparent correlation between diarrhea and microsporidian infection.

HIV− and HIV+ TB patients.

The HIV− and HIV+ patients being treated at the Jamot Tuberculosis Hospital were examined for microsporidian infections (Table 1). There was no significant difference between the prevalence of microsporidia in stool samples obtained from TB patients that also were infected with HIV and the prevalence of microsporidia in samples from those who were not infected with HIV. Only six of the HIV+ TB patients had diarrhea, and microsporidian spores were not found in four of these cases; the other two had parasite infection scores of only +1 and +2. Thus, there was no correlation between being HIV+ and having diarrhea and shedding of microsporidian spores.

TABLE 1.

Microsporidian infections in HIV-negative and HIV-positive TB patients hospitalized in the Jamot Tuberculosis Hospital

| HIV status of TB patients | No. of patients with infection score:

|

Total no. of patients in group | Prevalence (% infected) | Mean infection scorea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | +1 | +2 | +3 | +4 | ||||

| Positive | 18 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 28 | 35.7 | +1.9 |

| Negative | 19 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 24.0 | +1.2 |

Mean infection scores of those with microsporidiosis, as determined by the formula [Σ (infection score × number of specimens)]/number infected.

Repeat samplings were performed 7 days apart on four TB patients, of which two were HIV positive. Microsporidian spores were not detected in stool samples obtained in the first or second sampling from these four patients.

Healthy individuals.

The prevalence of microsporidiosis among the immunocompetent people surveyed was remarkably high. Surprisingly, 67.5% of the 126 people who were designated healthy individuals were positive for microsporidiosis. The prevalence rates among healthy people were significantly different (P < 0.001) from those of both groups of hospitalized TB patients.

Most samples were obtained from adults, and thus individuals were separated according to age groups to normalize the prevalence (the percentage of the total in each group). The lowest percentage of infection was among infants, and the highest percentage of infection was among teenagers and the elderly (Table 2). The prevalence rates between infants and teenagers were significantly different (P < 0.025). However, the mean infection scores of those with microsporidiosis indicated that children had the highest parasite loads (i.e., were shedding the highest number of spores).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of healthy individuals infected with microsporidia by age and gender

| Age group (yr) | No. of females (% infected) | No. of males (% infected) | Total no. in study (% infected) | Mean infection scorea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants (0-5) | 4 (25.0) | 4 (50.0) | 8 (37.5) | +1.7 |

| Children (6-11) | 8 (62.5) | 8 (62.5) | 16 (62.5) | +2.5 |

| Teenagers (12-19) | 15 (73.3) | 12 (91.7) | 27 (81.5) | +1.7 |

| Adults (20-50) | 34 (70.6) | 34 (58.8) | 68 (64.7) | +1.9 |

| Elderly (>50) | 2 (50.0) | 5 (100.0) | 7 (85.7) | +1.7 |

Mean infection scores of those with microsporidiosis, as determined by the formula [Σ (infection score × number of specimens)]/number infected.

The percentages of immunocompetent people with the indicated parasite load scores were the following: +1, 32.9% (28/85); +2, 50.6% (43/85); +3, 10.6% (9/85); and +4, 5.8% (5/85). The mean infection score for this study group was +1.9 ± 0.1 standard error of the mean. In contrast, only one HIV+ patient in this study was shedding spores at the +4 level. Thus, healthy people commonly had high parasite loads.

There were 13 households of healthy people in this study. On average, 67.7% of individuals occupying the same residence were positive for microsporidia (Table 3). In three cases, all members of the same household that had been examined were infected. One of these households had 11 family members, and high levels of spore shedding were observed; the mean infection score for this household was +2.5.

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of microsporidiosis in healthy individuals within the same household

| Household no. | Total no. of individuals in household | No. (%) of individuals infected with E. bieneusi | No. of individuals with parasite load:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | +1 | +2 | +3 | +4 | |||

| 1 | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 2 | 1 (50.0) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 3 | 3 (100.0) | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 4 | 3 (75.0) | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | 4 | 4 (100.0) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 | 5 | 3 (60.0) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | 5 | 4 (80.0) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 6 | 5 (83.3) | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| 9 | 7 | 5 (71.4) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 7 | 3 (42.9) | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 11 | 8 | 5 (62.5) | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 11 | 6 (54.5) | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 13 | 11 | 11 (100.0) | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

The prevalence rates for the people inhabiting the four different urban neighborhoods were the following: Nlongkak, 80.0% (12/15); Biyem-Assi, 77.5% (31/40); Quartier General, 63.3% (31/49); and Bonamoussadi, 60.0% (9/15). Living conditions in these neighborhoods generally were comparable, and microsporidiosis prevalence rates were not significantly different between them.

Immunofluorescence identification of Enterocytozoon bieneusi.

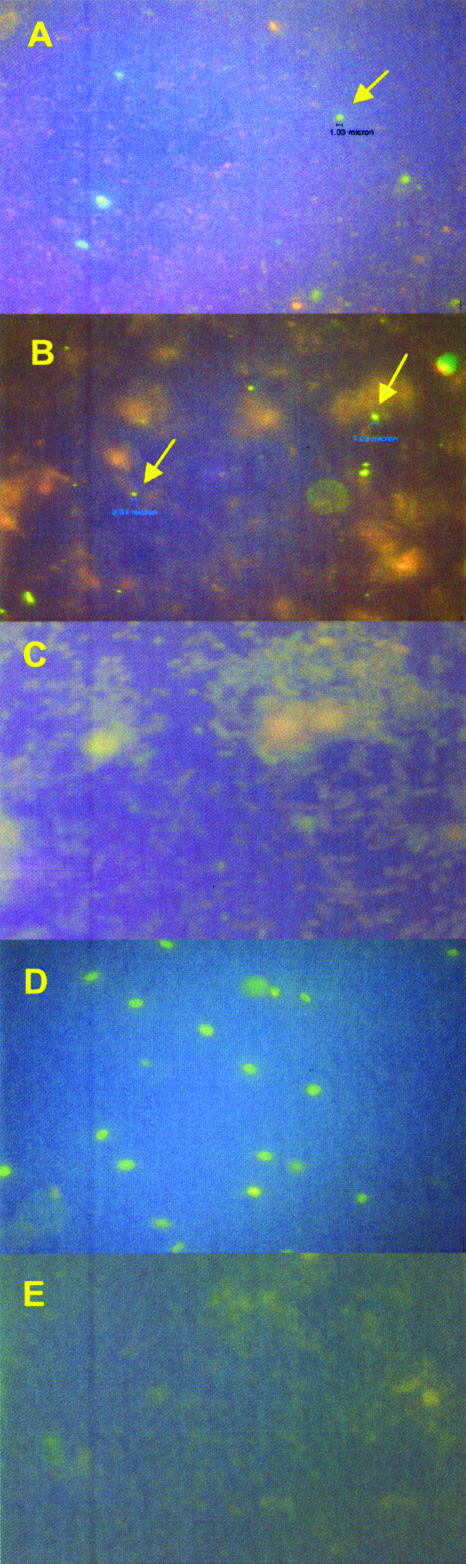

All 12 specimens examined that were designated microsporidian positive by calcofluor staining contained spores that tested positive for Enterocytozoon bieneusi by IFA using anti-Enterocytozoon bieneusi MAb (Fig. 2A and B). Enterocytozoon bieneusi clusters were observed in all of these specimens, 11 of which were obtained from healthy people. The three samples designated microsporidian negative by calcofluor staining (one from a healthy person and the other two from patients in the TB hospital) also tested negative for Enterocytozoon bieneusi by IFA (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

IFAs of stool samples. (A) Sample scored as microsporidian positive by calcofluor staining. The specimen was incubated with IgG MAb directed against Enterocytozoon bieneusi. The fluorescing spore (arrow) has a diameter of 1.03 μm, which is in the range of spores of this species. (B) Sample scored as microsporidian positive by calcofluor staining. The specimen was incubated with IgG MAb directed against Enterocytozoon bieneusi. The spore on the left exhibiting fluorescence (arrow) has a diameter of 0.08 μm, and the one on the right (arrow) is 1.03 μm in diameter. (C) Fecal sample scored as microsporidian negative by calcofluor staining. The specimen was incubated with IgG MAb directed against Enterocytozoon bieneusi; fluorescing bodies of ∼1 μm were not observed. (D) Encephalitozoon intestinalis spores from cultured organisms incubated with IgG MAb directed against Encephalitozoon intestinalis. These spores exhibit fluorescence, indicating that this MAb preparation bound to the Encephalitozoon intestinalis organisms and that these spores are larger than those observed in the fecal specimens examined in this study. (E) Fecal samples scored by calcofluor staining as Enterocytozoon bieneusi positive, with a +4 parasite load. The specimen was incubated with IgG MAb directed against Encephalitozoon intestinalis. No fluorescing spores of ∼1 μm were detected.

The anti-Enterocytozoon bieneusi MAb showed no cross-reactivity with Encephalitozoon intestinalis. Spores obtained from cultured Encephalitozoon intestinalis did not fluoresce when incubated with anti-Enterocytozoon bieneusi MAb, whereas they exhibited intense fluorescence when incubated with MAb directed against Encephalitozoon intestinalis (Fig. 2D). No Encephalitozoon intestinalis spores were detected in any of the fecal samples analyzed in this study, as indicated by incubating specimens with MAb directed against Encephalitozoon intestinalis (Fig. 2E).

DISCUSSION

There are now reports on microsporidiosis from several African countries (1, 4, 13, 14, 19-24). Stool samples analyzed in most of those studies were obtained from HIV+ patients, and the detection of spores ranged from <1% to <20% in the study groups. The first report on microsporidiosis in Yaoundé, Cameroon, was published in 1997 (19). Analyses were performed on 66 HIV+ patients with diarrhea, of which 8.8% were found to be positive for Enterocytozoon bieneusi. Recently, 5.2% of 154 HIV+ patients in Yaoundé were reported to have Enterocytozoon bieneusi in their stools (21). In contrast to those reports, the present study detected a much higher percentage (35.7%) of HIV+ patients with microsporidiosis. The reason for this difference might be explained by the selection of HIV+ patients in this study; 28 of these 29 patients were infected with both Mycobacterium tuberculosis and HIV. Another difference between the previous reports and the present study might be the diagnostic strategies employed; in the present study, highly sensitive calcofluor staining was employed. Immunofluorescence analysis verified the identity of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in these Yaoundé fecal samples. While these initial IFA studies indicated that the microsporidia in randomly selected samples were Enterocytozoon bieneusi and not Encephalitozoon intestinalis, the presence of other microsporidian species cannot be ruled out, since only anti-Enterocytozoon bieneusi and anti-Encephalitozoon intestinalis antibodies were available and tested in the present study.

The only other report of such a high prevalence of microsporidian infections that we are aware of is that of a group of 243 Ugandan children with persistent diarrhea, of which 32.9% were shedding Enterocytozoon bieneusi. In that study, 91 of those 243 children also were infected with HIV, and 70 (76.9%) had microsporidiosis (22). In another study, analysis of preserved specimens obtained during several years found that 51.5% of 31 HIV patients in Portugal during 1996 had microsporidiosis (12). Most infections in that study were due to Encephalitozoon intestinalis, and a lower percentage of patients had Enterocytozoon bieneusi.

Most studies on human microsporidiosis have been limited to studies on HIV-infected patients with diarrhea. However, in a few cases, infections in immunocompetent people also have been observed (14, 17). With respect to the elderly, a study in Spain reported that 17% of 60 elderly HIV-negative patients were infected with microsporidia (17). In contrast, although there were only six immunocompetent elderly subjects (≥50 years of age) in the present study, all were found to be infected with microsporidia.

Prevalence rates reported among AIDS patients with chronic diarrhea ranged from 7 to 50% (6). While some studies found a correlation between microsporidiosis and diarrhea (7), others did not (8). Shedding of spores is intermittent, and it is known that patients diagnosed with microsporidiosis by analysis of biopsy material may have had stools devoid of the parasite (5, 7). Thus, the prevalence of microsporidiosis in both HIV+ patients and the healthy immunocompetent population in Yaoundé would be expected to be even higher than the analysis of stool indicates.

Most microsporidian spore clusters observed in this study were found in specimens from healthy people. Clusters are likely the result of epithelial cells sloughed off that contained microsporidia and then broke apart at some point along the intestinal tract (i.e., deterioration of host cell membranes during expulsion of feces), leaving the microsporidia still closely clustered. It is not clear whether microsporidian clusters correlated with pathogenesis.

This study of the prevalence of microsporidia found among healthy people in Yaoundé involved more subjects than any other study and had the highest prevalence rate reported for immunocompetent people. The results of this study suggest that the general native population of Yaoundé, and perhaps of the general region in sub-Saharan Africa, are chronically infected with the parasite and have developed high tolerance to the infection. It has been suggested that pathogenic microsporidiosis emerged in humans only recently and concurrently with the AIDS pandemic (2). The observations made in this study suggest that microsporidiosis was prevalent among people in Cameroon prior to the emergence of AIDS. However, because these are very small organisms, they might have gone unnoticed until people became aware of AIDS-associated opportunistic infections.

The paradigm of AIDS-associated opportunistic infections is infection with Pneumocystis jirovecii, the causative agent of Pneumocystis pneumonia in immunodeficient individuals. It is known that colonization or transient infection of healthy people is widespread, as indicated by the high seroprevalence of antibodies against this organism worldwide (25). In a similar manner, microsporidiosis might cause only mild, self-limiting diarrhea in immunocompetent individuals who are capable of clearing the infection. Immunocompetent laboratory rodents inoculated with microsporidia, for example, typically exhibit mild clinical signs during the acute or early stage of infection that resolve, even though the infection persists (11). Furthermore, reinfection might be frequent due to suboptimal sanitary conditions that favor the spread of organisms throughout the human population in Cameroon. The observations made in the present study of individual households are consistent with transient infections in immunocompetent hosts; the stool samples of some members of a household contained microsporidian spores, while samples from other members of that same household did not. However, since this study did not include longitudinal observations on the same individuals, the nature of sporadic shedding of microsporidian spores also might explain the variations seen in infections within households. On the other hand, it cannot be ruled out that, as HIV/AIDS became widespread in this region of Africa, microsporidia truly emerged as opportunistic pathogens in these patients, and then, more recently, the parasite (or a less virulent mutant strain) spread throughout the general population.

To shed light on the natural history and epidemiology of this parasite in Cameroon, it is important to perform follow-up analyses of the same individuals examined in this study, especially the healthy volunteers in Yaoundé. Additional studies of people living in rural villages and from different regions of the country also should be performed. Furthermore, high-resolution analyses of microspordian DNA sequences, such as that provided by the internal transcribed spacer region of the rRNA gene, should be performed (3). Genotyping of organisms isolated from HIV+ patients and healthy people might determine whether there are microsporidia of various levels of virulence. These studies also might provide insights into whether there was widespread colonization of microsporidia in humans in Cameroon, which then caused life-threatening infections with the emergence of AIDS in this region of Africa.

Acknowledgments

We thank Edward Ndzi and Chelea Matawe for assistance in collecting fecal samples, Christopher Kuaban for facilitating specimen collecting at the Jamot Tuberculosis Hospital, Lisa Bowers for assistance in analyzing fecal smears, and Saul Tzipori for providing the anti-Enterocytozoon bieneusi MAb preparation.

This work was supported in part by NIH grants RO1 AI064084 to E.S.K. and AI039968 and RR00164 to E.S.D.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfa Cisse, O., A. Ouattara, M. Thellier, I. Accoceberry, S. Biligui, D. Minta, O. Doumbo, I. Desportes-Livage, M. A. Thera, M. Danis, and A. Datry. 2002. Evaluation of an immunofluorescent-antibody test using monoclonal antibodies directed against Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis for diagnosis of intestinal microsporididosis in Bamako (Mali). J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1715-1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambriose-Thomas, P. 2000. Emerging parasite zoonoses: the role of host-parasite relationship. Int. J. Parasitol. 30:1361-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bern, C., V. Kawai, D. Vargas, J. Rabke-Verani, J. Williamson, R. Chavez-Valdez, L. Xiao, I. Sulaiman, A. Vivar, E. Ticona, M. Ñavincopa, V. Cama, H. Moura, W. E. Secor, G. Visvesvara, and R. H. Gilman. 2005. The epidemiology of intestinal microsporidiosis in patients with HIV/AIDS in Lima, Peru. J. Infect. Dis. 191:1658-161664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cegielski, J. P., Y. R. Ortega, S. McKee, J. F. Madden, L. Gaido, D. A. Schwartz, K. Manji, A. F. Jorgensen, S. E. Miller, U. P. Pulipaka, A. E. Msengi, S. H. Mwakyusa, C. R. Sterling, and L. B. Reller. 1999. Cryptosporidium, Enterocytozoon, and Cyclospora infections in pediatric and adult patients with diarrhea in Tanzania. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:314-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarridge, J. E., III, S. Karkhanis, L. Rabeneck, B. Marino, and L. W. Foote. 1996. Quantitative light microscopic detection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in stool specimens: a longitudinal study of human immunodeficiency virus-infected microsporidiosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:520-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conteas, C. N., E. S. Didier, and O. G. Berlin. 1997. Workup of gastrointestinal microsporidiosis. Dig. Dis. 15:330-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coyle, C. M., M. Wittner, D. P. Kotler, C. Noyer, J. M. Orenstein, H. B. Tanowitz, and L. M. Weiss. 1996. Prevalence of microsporidiosis due to Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon (Septata) intestinalis among patients with AIDS-related diarrhea: determination by polymerase chain reaction to the microsporidian small-subunit rRNA gene. Clin. Infect. Dis. 23:1002-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dascomb, K., R. Clark, J. Aberg, J. Pulvirenti, R. G. Hewitt, P. Kissinger, and E. S. Didier. 1999. Natural history of intestinal microsporidiosis among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3421-3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Didier, E. S., J. M. Orenstein, A. Aldras, D. Bertucci, L. B. Rogers, and F. A. Janney. 1995. Comparison of three staining methods for detecting microsporidia in fluids. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:3138-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Didier, E. S., L. B. Rogers, J. M. Orenstein, M. D. Baker, C. R. Vossbrinck, T. van Gool, R. Hartskeerl, R. Soave, and L. M. Beaudet. 1996. Characterization of Encephalitozoon (Septata) intestinalis isolates cultured from nasal mucosa and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids of two AIDS patients. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 43:34-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Didier, E. S. 2005. Microsporidiosis: an emerging and opportunistic infection in humans and animals. Acta Trop. 94:61-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferreira, F. M., L. Bezerra, M. B. Santos, R. M. Bernardes, I. Avelino, and M. L. Silva. 2001. Intestinal microsporidiosis: a current infection in HIV-seropositive patients in Portugal. Microbes Infect. 3:1015-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gumbo, T., I. T. Gangaidzo, S. Sarbah, A. Carville, S. Tzipori, and P. M. Wiest. 2000. Enterocytozoon bieneusi infection in patients without evidence of immunosuppression: two cases from Zimbabwe found to have positive stools by PCR. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 94:699-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gumbo, T., S. Sabrá, I. T. Gangaidzo, Y. Ortega, C. R. Sterling, A. Carville, S. Tzipori, and P. M. Wiest. 1999. Intestinal parasites in patients with diarrhea and human immunodeficiency virus infection in Zimbabwe. AIDS 13:819-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keele, B. F., F. Van Heuverswyn, Y. Li, E. Bailes, J. Takehisa, M. L. Santiago, F. Bibollet-Ruche, Y. Chen, L. V. Wain, F. Liegeois, S. Loul, E. M. Ngole, Y. Bienvenue, E. Delaporte, J. F. Brookfield, P. M. Sharp, G. M. Shaw, M. Peeters, and B. H. Hahn. 2006. Chimpanzee reservoirs of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1. Science 313:523-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levine, J., and E. G. Estevez. 1983. Methods for concentration of parasites from small amounts of feces. J. Clin. Microbiol. 18:786-788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lores, B., I. Lopez-Miragaya, C. Arias, S. Fenoy, J. Torres, and C. del Aguila. 2002. Intestinal microsporidiosis due to Enterocytozoon bieneusi in elderly human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients from Vigo, Spain. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:918-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melvin, D. M., and M. Brooke. 1982. Laboratory procedures for the diagnosis of intestinal parasites, 3rd ed. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.

- 18a.Ministry of Public Health and Cameroon National AIDS Control Committee. 2004. Preliminary results of the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS-III). Ministry of Public Health, Yaoundé, Cameroon.

- 19.Samé-Ekobo, A., J. Lohoué, and A. Mbassi. 1997. Étude clinique et biologique des diarrhées parasitaires et fongiques chez les sujets immuodéprimés dans la zone urbaie et péri-urbaine de Yaoundé. Cahiers Santé 7:349-354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samie, A., C. L. Obi, S. Tzipori, L. M. Weiss, and R. L. Guerrant. 2007. Microsporidiosis in South Africa: PCR detection in stool samples of HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals and school children in Vhembe district, Limpopo Province. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 101:547-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarfati, C., A. Bourgeois, J. Menotti, F. Liegeois, R. Moyou-Somo, E. Delaporte, F. Derouin, E. M. Ngole, and J. M. Molina. 2006. Prevalence of intestinal parasites including microsporidia in human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 74:162-164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tumwine, J. K., A. Kekitiinwa, S. Bakeera-Kitaka, G. Ndeezi, R. Downing, X. Feng, D. E. Akiyoshi, and S. Tzipori. 2005. Cryptosporidiosis and microsporidiosis in Ugandan children with persistent diarrhea with and without concurrent infection with the human immunodeficiency virus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 73:921-925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tumwine, J. K., A. Kekitiinwa, N. Nabukeera, D. E. Akiyoshi, M. A. Buckholt, and S. Tzipori. 2002. Enterocytozoon bieneusi among children with diarrhea attending Mulago Hospital in Uganda. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 67:299-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Gool, T., E. Luderhoff, K. J. Nathoo, C. F. Kiire, J. Dankert, and P. R. Mason. 1995. High prevalence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi infections among HIV-positive individuals with persistent diarrhoea in Harare, Zimbabwe. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 89:478-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walzer, P. D., and M. T. Cushion (ed.). 2005. Pneumocystis pneumonia. Lung biology in health and disease, 3rd ed., vol. 194. Marcel Dekker, New York, NY.

- 26.Wittner, M., and L. M. Weiss (ed.). 1999. The microsporidia and microsporidiosis. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 27.Zhang, Q., I. Singh, A. Sheoran, X. Feng, J. Nunnari, A. Carville, and S. Tzipori. 2005. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies against Enterocytozoon bieneusi purified from rhesus macaques. Infect. Immun. 73:5166-5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]