Abstract

This study compared two commercially available assays for the measurement of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA levels, the Bayer HCV RNA (version 3.0) branched DNA assay and the Abbott HCV analyte-specific reagent real-time PCR assay, to assess their quantitative relationships, ease of performance, and time to completion. The study group consisted of randomly selected patients from the NIAID human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) outpatient clinic who were infected with HIV type 1 and HCV. One hundred eighty-four samples from 66 patients coinfected with HIV and HCV receiving treatments under various protocols were analyzed for the correlation and agreement of the results. The results indicated that the two assays correlate well in the overlapping linear ranges of the assays and show good agreement. From the results obtained, we have derived a mathematical formula to compare the viral load results between the two assays, which is given as log10 Abbott assay measure = 0.032 + 1.01 log10 Bayer assay measure. Although it is preferable to use the same quantitation assay throughout the course of a patient's treatment, valid comparisons of the HCV RNA levels may be made between the results obtained by either of these assays in the overlapping linear range (615 to 7,700,000 IU/ml).

It is estimated that approximately 4.1 million people in the United States, i.e., 1.6% of the population (information found at the CDC Viral Hepatitis C website [http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/hepatitis/c/fact.htm]), and that 270 million to 300 million people worldwide, i.e., 3% of the world's population (information found at the Hepatitis C Information Center website [http://www.hepatitis-central.com]), are infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV). It has been called the “silent epidemic” because, frequently, those infected with HCV have no symptoms or their symptoms are mild and nonspecific. About 80% of those newly infected will ultimately progress to chronic infection, and of those, 10 to 20% will develop cirrhosis and 1 to 5% will develop liver cancer over a period of 20 to 30 years (1). HCV patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) progress more rapidly to liver cirrhosis than those who are not coinfected with HIV (2).

Unlike HIV, HCV is a curable infection (16, 19), with cure rates of 98% among HIV-negative patients in the acute stage of infection and 26 to 40% among HIV-positive patients (13) following therapy with the FDA-approved regimen of a combination of peg-interferon and ribaviran (4, 14). Experimental therapies, including viramidine, valopicitabine, and SCH503034, an NS3 protease inhibitor, are currently being tested in phase I/II clinical trials. The ability of clinicians to evaluate the efficacies of anti-HCV drug protocols for their patients is partially dependent on their ability to monitor the HCV load over time (10). Both the absolute viral load and the log decline in the viral load from the baseline were found to be clinically useful for predicting a sustained virological response or the lack of a sustained virological response to treatment (15, 21, 22). Unfortunately, despite the use of universal international standards (IU), the results obtained by different methods may vary (9, 12). It is important to determine how assays are related in the event that a patient is monitored by the use of more than one method. Two currently available methods of HCV load measurement are the Bayer Versant HCV RNA (version 3.0) branched DNA (bDNA) assay and the Abbott analyte-specific reagent (ASR) HCV real-time PCR protocol. In this paper we compare the results obtained by these assays, as well as their time to completion and ease of performance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

This was a retrospective cohort study performed with 184 archived plasma samples obtained from 66 patients infected with a variety of HCV genotypes participating in NIAID intramural HIV clinical trials at the National Institutes of Health. All patients signed an informed consent approved by the NIAID Institutional Review Board.

Sample collection and processing.

Whole, EDTA-preserved blood was collected from patients. The plasma was separated within 2 h of collection and was distributed as 1-ml aliquots. The aliquots were placed into a −20°C freezer for pickup, which occurs within 12 h. They are thawed once for the assay and are refrozen at −20°C for repeat assays, if necessary. In our evaluation of the Abbott system, we not only used samples thawed once, held at 4°C, and run within 24 h on both instruments, but we also used samples which were run previously on the Bayer system, before we acquired the Abbott system, and immediately frozen. Our experience with this procedure of rerunning samples has shown excellent RNA recovery. Studies show that plasma samples may be held for up to 7 days at 4°C and 5 years at −20°C and may be frozen-thawed up to three times with no ill effects on RNA recovery (8, 11, 18).

Viral load quantitation.

Viral load quantitation was performed by the VERSANT HCV RNA (version 3.0) assay (a bDNA assay) with a Q340 instrument (Bayer Healthcare LLC, Diagnostics Division, Tarrytown, NY), following the manufacturer's instructions, and the Abbott ASR HCV assay on an ABI 7000 real-time PCR instrument by following a protocol developed in-house. Essentially, RNA was extracted from plasma samples by using a QIAamp viral RNA minikit (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, CA) with an internal standard provided by Abbott. The extracted RNA was then combined with Abbott oligonucleotides, manganese, and polymerase and placed in the ABI 7000 instrument, where the RNA was converted to cDNA, which was subsequently amplified. Total RNA was quantitated by comparing the values with the values obtained with the internal standard.

The bDNA assay is a signal amplification assay with a linear range from 615 to 7,700,000 IU/ml and a 95% detection rate at 1,000 IU/ml. It requires 50 μl of plasma. The real-time PCR assay is a target amplification assay and has an accepted linear range in our laboratory of 10 to 25,000,000 IU/ml. It requires 250 μl of plasma. The lower limit and linearity of the Abbott assay were assessed by quadruplicate testing of a linearity panel consisting of samples with HCV titers ranging from 0 to 5 × 106 IU/ml (BBI Diagnostics, West Bridgewater, MA). Since no commercially available panel that contained a member with an HCV titer greater than 5 × 106 IU/ml was found, the upper limits, accuracy, and precision of the assay were determined by repeat testing of the samples previously quantified by the Bayer bDNA assay. Eleven samples were tested over three separate runs and in replicates (duplicate or more) within each run to evaluate the intra-assay and the interassay precisions.

Comparative analysis.

For results that fell in the overlapping dynamic range of the assays, least-square regression was used to find the relationship between the Bayer and Abbott assay measures. A scatter plot was used to compare all values from the two assays, both those that were detectable and those that were below or above the limit of detection. Multiple outputation was used as a tool to handle multiple observations within a subject (6). We used the methods of Bland and Altman to determine the agreement between the assays (3).

RESULTS

Equivalence of measures.

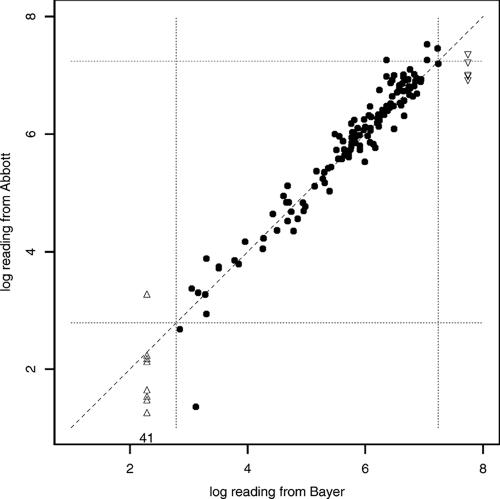

A scatter plot of viral load readings from the Bayer and Abbott assays revealed that 41 samples (of 184) had viral loads of <10 IU/ml (the lower limit of detection) by the Abbott assay. The same 41 samples had viral loads of <615 IU/ml (lower limit of detection) by the Bayer assay (Fig. 1). An additional 8 samples had viral loads of <615 IU/ml by the Bayer assay. Their values ranged from 18 to 1,900 IU/ml by the Abbott assay, with an average of 311 IU/ml and a standard deviation of 645 IU/ml. This relatively large standard deviation is due to one sample with a reading of 1,900 IU/ml, while all the other samples had readings below 180 IU/ml.

FIG. 1.

Scatter plot of the Abbott assay readings versus the Bayer assay readings. Solid dots, samples in which RNA was detectable by both assays; triangles, samples with RNA undetectable by the Bayer assay (HCV was present at levels either below the lower detection limit or above the upper detection limit) but detectable by the Abbott assay. In addition, there were 41 samples with RNA undetectable by both assays (Bayer assay reading, <615 IU/ml; Abbott assay reading, <10 IU/ml). The four dashed lines specify the linear range for the Bayer assay, and the broken line is that of identity.

A total of 130 samples from 55 patients had detectable RNA by both tests. For 24 of these 55 patients, there were multiple observations of the HCV load over time. If the mean value of the multiple observations is used as the measure for each patient, linear regression of the Abbott assay measure versus the Bayer assay measure gives an intercept of 0.06 (95% confidence interval [CI], −0.18, 0.30) and a slope of 1.01 (95% CI, 0.94, 1.09). This regression is performed with both measures on a log10 scale and is centered around log10(615) = 2.79, i.e., log10(Bayer assay measure) − 2.79 versus log10(Abbott assay measure) − 2.79. An intercept of about 0 indicates that the two measures are about the same for viral loads near 615. A slope of about 1 indicates that for every 1 unit of change in the Bayer assay measure, there is about 1 unit of change in the Abbott measure.

Thus, for the samples for which both tests showed detectable HCV load readings (615 IU/ml to 7,700,000 IU/ml), the linear regression result indicates equivalence between the Abbott and Bayer assay measures. Overall, the percent CVs across the range are higher for the Abbott assay than those claimed by Bayer for the bDNA assay. For samples with viral loads ranging from 5,000,000 to 100,000,000, the Abbott assay average interassay CV was 44% and the intra-assay CV was 20%, whereas Bayer reports (HCV RNA 3.0 bDNA assay package insert) that the average interassay CV is 17% and that the intra-assay CV is 13.9%. For samples with viral loads between 1,000 and 5,000,000 IU/ml, the Abbott assay average interassay CV was 27% and the intra-assay CV was 20%, whereas the reported Bayer assay average interassay CV is 18.3% and the intra-assay CV is 11.7%. For samples with viral loads below 100 IU/ml, the Abbott assay interassay CV was 56% and the intra-assay CV was 51%, whereas the reported Bayer assay average interassay CV is 35.2% and the intra-assay CV is 28.7%.

Multiple outputation can be applied to handle the multiple HCV observations within a subject. That is, for subjects with multiple observations, we randomly picked one observation and then did the linear regression for these resampled data to obtain an estimate of the intercept and the slope. We repeated the procedure of “within-subject resampling” and estimation; the average of the estimated intercepts (or slopes) over the resampled data is the multiple outputation estimate of the intercept (or slope). It yields results similar to those presented from regression of the averages, with an estimate of the intercept of 0.04 and an estimate of the slope of 1.02.

Agreement between measures.

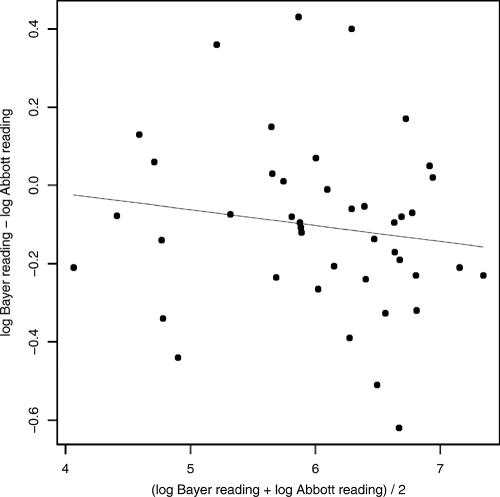

A Bland-Altman plot shows the differences between two measures (on the y axis) versus the averages of the two measures (on the x axis), which helps to determine how the measurements from two methods agree with each other.

For the detectable viral load readings (both on a log10 scale), we used linear regression of the differences between the two readings versus the averages of the two readings. The estimated coefficients of this linear regression are all close to 0: the intercept is 0.19 (P value = 0.39) and the slope is −0.05 (P value = 0.19). The two P values, both >0.1, indicate that both the intercept and the slope are not significantly different from 0. Therefore, the Bland-Altman analysis shows that the viral load readings from the Bayer and the Abbott assays are almost the same and that the difference between the two readings is not related to the magnitude of the viral load (Fig. 2). In fact, for 95.3% of the subjects, the differences in the viral load readings from the Abbott and the Bayer assays were within 0.51 log10.

FIG. 2.

Plots of the differences between the viral load readings from the Bayer and Abbott assays versus the averages of the two assays. The line is from linear regression.

Formula for comparison of measures of HCV loads.

The linear regression was performed for both the Bayer and the Abbott readings centered around log10(615) = 2.79, so that the intercept indicates the difference in the two viral load readings at a viral load magnitude of 615 IU/ml. The estimated regression coefficients (intercept = 0.06 and slope = 1.01) give the relationship as (log10 Abbott assay measure − 2.79) = 0.06 + 1.01(log10 Bayer assay measure − 2.79). This can be simplified as log10 Abbott assay measure = 0.032 + 1.01 log10 Bayer assay measure.

Time to completion and ease of performance.

The Bayer Versant HCV RNA (version 3.0) bDNA assay requires an overnight (15- to 18-h) incubation of sample in the Q340 instrument for the hybridization of RNA with target probes (Table 1). The preparation of samples/reagents, the loading of the plate, and the placement of the plate into the instrument on day 1 are usually accomplished in 1 to 2 h. These steps are simple “recipe” mixing and pipetting procedures requiring moderate technical skill. Completion of the assay on day 2 is generally performed in 4 to 5 h and, again, requires the simple mixture of reagents and multichannel pipetting. The washing and reading of the plate are fully automated. Once the Q340 instrument reads the plate, the Bayer software yields a final, printed report automatically. Thus, the overall time required to obtain a result from the bDNA assay is roughly 20 to 25 h.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Abbott and Bayer HCV quantitation assays

| Parameter of comparison | Abbott | Bayer |

|---|---|---|

| Sample preparation time (h) | 1.5-3 | 1-2 |

| Skill level required for preparation/loading | High/moderate | Low/moderate |

| Overnight incubation time (h) | None | 15-18 h |

| Time (h) for completion of assay | 2.5-3 | 4-5 |

| Skill level required for day 2 procedure | NAa | Low |

| Analysis time (min) | 15-30 | NA |

| FDA approved | No | Yes |

| Simultaneous genotyping possible | Yesb | No |

| Simultaneous HIV load determination possible | No | Yesc |

| Automated sample preparation available | Yesb | No |

| Reagent-based instrument loan program | Yes | Yes |

| Total turnaround time (h) | 4.25-6.5 | 20-25 |

| Total technician timed (h) | 2.25-4.5 | 3.25-4.25 h |

| Cost estimate ($ [list price])/test for 50 tests | $213e | $174e |

NA, not applicable.

Additional cost.

Not FDA approved/additional cost.

For manual preparation.

The costs for consumables are not included; Bayer kit list price, $8,700 ($8,700/50 = $174); Abbott reagents list price plus QIAGEN extraction reagents, ($4,882.61 + $984.17 + $1,224 + $2,856 + $690)/50 = $213.

The Abbott HCV ASR assay requires a front-end RNA extraction step by use of the QIAGEN spin prep method. This procedure requires a moderate to high skill level but can usually be accomplished in 1.5 to 3 h, depending on the number of samples being extracted. Reagent preparation and addition of the reagents/samples to the optical plate are likewise fairly complex and require an additional 30 to 60 min. Once the plate is ready and placed in the ABI 7000 instrument, the real-time PCR and subsequent reading of the plate are automated and take approximately 2 h. Analysis of the raw data with the Abbott software may be completed in less than 30 min and yields a printable report. Thus, the overall time required to obtain a result from the Abbott ASR assay is approximately 4 to 6.5 h.

DISCUSSION

Serial measurement of the HCV load during therapy is an integral part of monitoring the efficacy of existing and new therapeutic approaches (7, 20, 22). This requires a sensitive and consistent means of quantitation of virus that allows comparison of the values from time point to time point. If patients switch treatment venues, it is possible that the mode of patient monitoring may change. In this case, it is useful to know how the two measures are comparable. In addition, laboratories questioning which method that they should use in their research may want to consider not only the initial investment in equipment and training, the capabilities of their technicians, and the time constraints within which they work but also the demands of the clinicians whom they are serving.

Both the Bayer HCV bDNA assay and the Abbott 7000 ASR assay yield consistent, reproducible results (17). Our comparison of the two systems for monitoring of the viral load revealed that both measures were equivalent when the results fell within detectable limits. The areas in which the two assays differed significantly are limit of detection, ease of performance, and time to completion.

Clinical studies rely on early virologic responses to determine the efficacies of therapeutic strategies consistently. Considering this, the Abbott assay has an advantage over the Bayer assay. Its lower limit of detection allows assessment of the viral load over a wider range of viral loads. For example, HCV was detected by the Abbott assay but not by the Bayer assay in eight samples obtained from six patients. (As mentioned above, all but one of these samples had HCV loads below 180 IU/ml, with a range of 18 to 1,900 IU/ml.) In addition, with the Abbott 7000 instrument and the Abbott ASR HCV genotyping reagents, it is possible to simultaneously determine the genotype while quantitating a sample. This may be a bonus to laboratories with limited space and time.

From an ease-of-performance standpoint, the Bayer assay has the advantage. There are fewer overall steps involved with setting up the assay, thus minimizing the potential for contamination, a problem with all PCR-based assays. In addition, while the assay involves more technical time on the second day, the steps are simple and the instrument provides automatic results, something not available with the Abbott 7000 instrument. In addition, it is possible to simultaneously run HCV and HIV load bDNA assays (5), making the Bayer assay an efficient and time-saving option in a laboratory conducting research on both analytes. Finally, as mentioned above, the Abbott assay shows less precision at the extremes of the viral load range.

In conclusion, although it is preferable to continuously monitor a patient by the same assay throughout a course of treatment, it is possible to compare the results obtained by the Abbott HCV quantitative ASR assay to the results obtained by the Bayer HCV (version 3.0) bDNA assay by using the formula derived from our results: log10 Abbott assay measure = 0.032 + 1.01 log10 Bayer assay measure.

In addition, from a laboratory perspective, the two assays give equivalent results when values fall within the overlapping detectable range, but each has advantages, depending upon the needs of the laboratory. Laboratories requiring a quick turnaround and coverage of a broad viral load range may consider the Abbott assay to be more suited to their needs. Laboratories concerned about simplicity of operation, high volume, and multiple analytes may prefer Bayer's bDNA assay. In either test, one may obtain reliable, reproducible results in a reasonable period of time. On the basis of the results of our testing, we believe that both assays are relatively robust and that our findings may easily be reproduced, provided that technicians are familiar with the molecular techniques involved and provided that they follow the manufacturer's instructions or in-house procedures as written.

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract N01-CO-12400. This research was also supported (in part) by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Subsequent to the submission of this paper, Bayer Healthcare LLC, Diagnostics Division, was purchased by Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alter, M. J., H. S. Margolis, K. Krawczynski, F. N. Judson, A. Mares, W. J. Alexander, P. Y. Hu, J. K. Miller, M. A. Gerber, R. E. Sampliner, et al. 1992. The natural history of community-acquired hepatitis C in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 327:1899-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benhamou, Y., M. Bochet, V. Di Martino, F. Charlotte, F. Azria, A. Coutellier, M. Vidaud, F. Bricaire, P. Opolon, C. Katlama, T. Poynard, et al. 1999. Liver fibrosis progression in human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus coinfected patients. Hepatology 30:1054-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bland, J. M., and D. G. Altman. 1986. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet i:307-310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung, R. T., J. Andersen, P. Volberding, G. K. Robbins, T. Liu, K. E. Sherman, M. G. Peters, M. J. Koziel, A. K. Bhan, B. Alston, D. Colquhoun, T. Nevin, G. Harb, and C. van der Horst. 2004. Peginterferon Alfa-2a plus ribavirin versus interferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C in HIV-coinfected persons. N. Engl. J. Med. 351:451-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elbeik, T., N. Markowitz, P. Nassos, U. Kumar, S. Beringer, B. Haller, and V. Ng. 2004. Simultaneous runs of the Bayer VERSANT HIV-1 version 3.0 and HCV bDNA version 3.0 quantitative assays on the system 340 platform provide reliable quantitation and improved work flow. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3120-3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Follmann, D., M. Proschan, and E. Leifer. 2003. Multiple outputation: inference for complex clustered data by averaging analyses from independent data. Biometrics 59:420-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forns, X., and J. Costa. 2006. HCV virological assessment. J. Hepatol. 44(Suppl. 1):S35-S39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gessoni, G., P. Barin, A. Frigato, M. Fezzi, G. de Fusco, N. Arreghini, P. Galli, and G. Marchiori. 2000. The stability of hepatitis C virus RNA after storage at +4 degrees C. J. Viral Hepat. 7:283-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halfon, P., G. Penaranda, M. Bourliere, H. Khiri, M. F. Masseyeff, and D. Ouzan. 2006. Assessment of early virological response to antiviral therapy by comparing four assays for HCV RNA quantitation using the international unit standard: implications for clinical management of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J. Med. Virol. 78:208-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes, C. A., and S. D. Shafran. 2006. Chronic hepatitis C virus management: 2000-2005 update. Ann. Pharmacother. 40:74-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jose, M., S. Curtu, R. Gajardo, and J. I. Jorquera. 2003. The effect of storage at different temperatures on the stability of hepatitis C virus RNA in plasma samples. Biologicals 31:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konnick, E. Q., S. M. Williams, E. R. Ashwood, and D. R. Hillyard. 2005. Evaluation of the COBAS hepatitis C virus (HCV) TaqMan analyte-specific reagent assay and comparison to the COBAS Amplicor HCV Monitor V2.0 and Versant HCV bDNA 3.0 assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2133-2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kottilil, S., J. O. Jackson, and M. A. Polis. 2005. Hepatitis B & hepatitis C in HIV-infection. Indian J. Med. Res. 121:424-450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manns, M. P., J. G. McHutchison, S. C. Gordon, V. K. Rustgi, M. Shiffman, R. Reindollar, Z. D. Goodman, K. Koury, M. Ling, and J. K. Albrecht. 2001. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet 358:958-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Bauer, E., J. Crespo, M. Romero-Gomez, R. Moreno-Otero, R. Sola, N. Tesei, F. Pons, X. Forns, and J. M. Sanchez-Tapias. 2006. Development and validation of two models for early prediction of response to therapy in genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 43:72-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel, K., A. J. Muir, and J. G. McHutchison. 2006. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. BMJ 332:1013-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross, R. S., S. Viazov, S. Sarr, S. Hoffmann, A. Kramer, and M. Roggendorf. 2002. Quantitation of hepatitis C virus RNA by third generation branched DNA-based signal amplification assay. J. Virol. Methods 101:159-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sebire, K., K. McGavin, S. Land, T. Middleton, and C. Birch. 1998. Stability of human immunodeficiency virus RNA in blood specimens as measured by a commercial PCR-based assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:493-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherman, M., E. M. Yoshida, M. Deschenes, M. Krajden, V. G. Bain, K. Peltekian, F. Anderson, K. Kaita, S. Simonyi, R. Balshaw, and S. S. Lee. 2006. Peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C patients who failed previous interferon therapy. Gut 55:1631-1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiffman, M. L., A. Ferreira-Gonzalez, K. R. Reddy, R. K. Sterling, V. A. Luketic, R. T. Stravitz, A. J. Sanyal, C. T. Garrett, M. De Medina, and E. R. Schiff. 2003. Comparison of three commercially available assays for HCV RNA using the international unit standard: implications for management of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection in clinical practice. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 98:1159-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terrault, N. A., J. M. Pawlotsky, J. McHutchison, F. Anderson, M. Krajden, S. Gordon, I. Zitron, R. Perrillo, R. Gish, M. Holodniy, and M. Friesenhahn. 2005. Clinical utility of viral load measurements in individuals with chronic hepatitis C infection on antiviral therapy. J. Viral Hepat. 12:465-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trimoulet, P., V. de Ledinghen, J. Foucher, L. Castera, H. Fleury, and P. Couzigou. 2004. Predictive value of early HCV RNA quantitation for sustained response in nonresponders receiving daily interferon and ribavirin therapy. J. Med. Virol. 72:46-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]