Abstract

“The higher the volume of blood cultured the higher the yield of blood cultures” has been a well-accepted dictum since J. A. Washington II performed his classic work. This rule has not been questioned in the era of highly automated blood culture machines, nor has it been correlated with clinical variables. Our objective in this study was to complete a prospective analysis of the relationship between blood volume, the yield of blood cultures, and the severity of clinical conditions in adult patients with suspected bloodstream infections (BSI). During a 6-month period, random samples of blood cultures were weighed to determine the volume of injected blood (weight/density). Overall, 298 patients with significant BSI and 303 patients with sepsis and negative blood cultures were studied. The mean volume of blood cultured in patients with BSI (30.03 ± 14.96 ml [mean ± standard deviation]) was lower than in patients without BSI (32.98 ± 15.22 ml [P = 0.017]), and more episodes of bacteremia were detected with <20 ml (58.9%) than with >40 ml (40.2%) of blood cultured (P = 0.022). When patients were stratified according to the severity of their underlying condition, patients with BSI had higher APACHE II scores, and higher APACHE II scores were related to lower sample volumes (P < 0.001). A multivariate analysis showed that in the group of patients with APACHE II scores of ≥18, higher volumes yielded higher rates of bacteremia (odds ratio, 1.04 per ml of blood; 95% confidence interval, 1.001 to 1.08). We conclude that the higher yield of blood cultures inoculated with lower volumes of blood reflects the conditions of the population cultured. Washington's dictum holds true today in the era of automated blood culture machines.

According to the classic literature, the volume of blood per culture is the single most important variable in recovering microorganisms from patients with sepsis. The higher the blood volume cultured, the higher the rate of detection of bloodstream infections (BSI) (1, 5-7, 9, 12, 15, 18, 20, 21). However, reports regarding the requirements for blood volume with today's automated and continuous-monitoring blood culture systems are scarce (12, 15, 22, 24). In a previous study, we noted that blood cultures inoculated with lower volumes had a higher yield of detection of BSI at our institution (17).

The aim of the present study was to reassess the importance of blood volume in the yield of blood cultures after the introduction of automated systems with continuous agitation and to correlate the findings with clinical variables.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our institution is a general teaching hospital with 1,750 beds serving a mainly urban population of 650,000. We have medical and surgical specialties as well as large psychiatric, obstetric, and pediatric facilities. We have very active bone marrow and solid organ transplantation programs and serve as a referral institution.

Study period and patient selection.

The study was carried out during a period of 6 months. We randomly selected one of every two episodes of significant BSI (patients) and approximately the same number of episodes of sepsis with negative blood cultures (controls). We included in the study only episodes with three sets of blood cultures drawn, which is our official recommendation.

In the case of microorganisms of doubtful significance (Bacillus spp., nonhemolytic Streptococcus spp., Propionibacterium acnes, Corynebacterium spp., Clostridium spp., and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp.), we considered to be clinically relevant only those with evidence of clinical manifestations of infection not explained by other causes, in which the microorganisms were isolated in two or more different blood cultures. For the few patients with recurrent bacteremia, we included only the first episode in the study.

Processing in the microbiology laboratory.

We used a continuous-monitoring blood culture system (BACTEC 9240; Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Sparks, MD) and BACTEC Aerobic Plus and Anaerobic Plus bottles that contained 25 ml of a standard culture medium. Each set of blood cultures consisted of one aerobic and one anaerobic bottle, which were inoculated with blood from a single puncture. According to the manufacturer's instructions, our laboratory recommendation is to fill each bottle with 7 to 10 ml of blood from adult patients. Blood culture bottles were incubated for 5 days. The identification of microorganisms was carried out by standard procedures.

Estimation of blood volume cultured.

We weighed the bottles from the three sets of blood cultures obtained from patients with clinical suspicion of infection. The blood volume cultured per bottle was calculated by subtracting the mean bottle weight before inoculation, according to the following formula: volume = weight of bottle with blood − mean weight of an empty bottle/density of blood (1,055 g/ml).

The mean volume of an “empty” bottle was calculated after weighing separately 50 aerobic blood culture bottles and 50 anaerobic bottles from two different lot numbers of medium before inoculation of the blood.

Microbiological data.

For each bottle we recorded the blood volume, the duration of incubation until detection of growth, and the microorganisms isolated.

Clinical data.

Clinical information for all patients included age, sex, hospital department, underlying diseases, comorbidity, severity of the clinical condition (Apache II scoring), and previous antimicrobial treatment. Predisposing factors for bacteremia were also recorded and included malnutrition, indwelling devices, orthopedic or vascular prosthesis, surgery, immunosuppression, neutropenia, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

Definitions. (i) Underlying disease and comorbidity.

We used the McCabe-Jackson scale, in which patients were stratified into three groups: the rapidly fatal group, the ultimately fatal group, and the nonfatal group (13). Comorbidity was assessed by the use of Charlson's comorbidity score (3).

(ii) Severity.

The severity of the clinical condition was assessed by the use of the APACHE II scoring system (11) at the time blood cultures were obtained.

Statistical analysis.

Relationships between variables collected were evaluated with the χ2 statistic for categorical variables, the t test for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Mann-Whitney test for nonparametric comparisons. Univariate correlates (P < 0.05) were then entered into stepwise logistic regression analyses. Factors with P values of <0.05 were retained in the model.

RESULTS

During the study period, 12,643 blood cultures were processed at our microbiology laboratory, and 2,716 turned out to be positive. They caused 581 episodes of significant bacteremia/fungemia. After random selection, the data set included 298 of the positive episodes (patients) and 303 episodes of sepsis syndrome with negative blood cultures for which three sets of blood cultures were drawn.

There were 354 microorganisms isolated in the 298 episodes of bacteremia/fungemia (42 corresponded to polymicrobial cases). The numbers and percentages of specific microorganisms isolated are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Numbers and percentages of specific microorganisms isolated in 298 episodes of positive blood cultures

| Microorganism | No. (%) of cases |

|---|---|

| Gram-positive bacteria | 195 (55.1) |

| S. aureus | 62 (17.5) |

| S. epidermidis/SCN | 49 (13.8) |

| Enterococcus sp. | 31 (8.8) |

| S. pneumoniae | 27 (7.6) |

| Other Streptococcus spp. | 25 (7.1) |

| Other | 1 (0.3) |

| Gram-negative bacteria | 135 (38.1) |

| E. coli | 66 (18.6) |

| Klebsiella sp. | 20 (5.6) |

| P. aeruginosa | 13 (3.7) |

| Proteus sp. | 11 (3.1) |

| Enterobacter sp. | 8 (2.3) |

| Salmonella sp. | 7 (1.9) |

| M. morganii | 2 (0.6) |

| Acinetobacter sp. | 2 (0.6) |

| Serratia sp. | 1 (0.3) |

| Citrobacter sp. | 1 (0.3) |

| Other | 4 (1.1) |

| Anaerobes | 16 (4.5) |

| Bacteroides sp. | 8 (2.3) |

| Clostridium sp. | 4 (1.1) |

| Other | 4 (1.1) |

| Fungi | 8 (2.3) |

| Candida sp. | 7 (2) |

| Other | 1 (0.3) |

| Total | 354 |

Mean volume of blood processed per patient.

The mean volume of blood processed per patient ± standard deviation was 31.52 ± 15.15 (3.51 to 103.73) ml. Each patient had three sets of blood cultures, with a mean volume of 10.42 ± 6.03 ml per blood culture (approximately 5 ml of blood per bottle). The mean blood volume cultured per patient with significant bacteremia/fungemia (30.03 ± 14.96 ml) was lower than the volume cultured for patients with negative blood cultures (32.98 ± 15.22 ml) (P, 0.017; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.52 to 5.36).

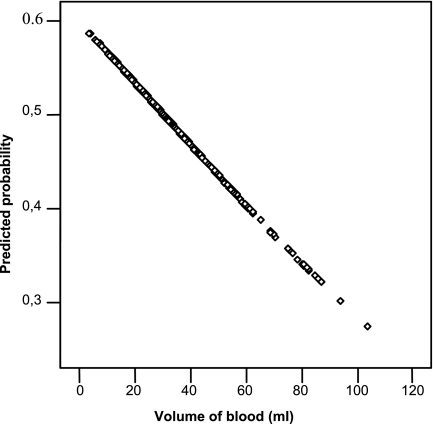

Table 2 shows the relationship between the volume of blood and the episodes of bacteremia/fungemia. By univariate analyses, there was an inverse relationship between blood volume cultured and the probability of detection of significant BSI (odds ratio [OR], 0.98; 95% CI, 0.976 to 0.998; P, 0.018) (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Relationship between volume of blood and number of episodes of bacteremia/fungemia detecteda

| Blood vol (ml) | No. of positive episodes/total (%) |

|---|---|

| <20 | 63/107 (58.9) |

| 20-30 | 123/234 (52.6) |

| 30-40 | 65/143 (45.5) |

| >40 | 47/117 (40.2) |

P = 0.022.

FIG. 1.

Relationship between volume of blood and probability of a positive blood culture (OR, 0.987; 95% CI, 0.976 to 0.998; P, 0.018).

Comparison of patients and controls.

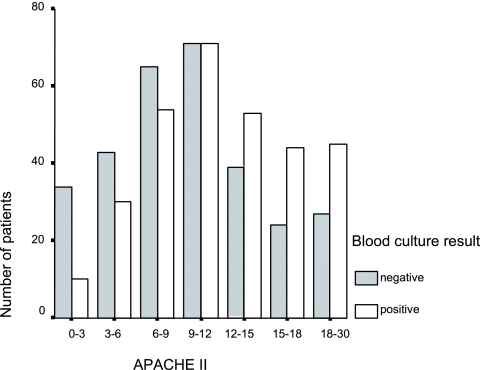

The characteristics of the patients enrolled in the study are presented in Table 3. By univariate analyses, eight variables were associated with the presence of BSI. The severity of patients' conditions at the time blood cultures were drawn was significantly associated with the presence of BSI, such that patients with BSI had a mean APACHE II score higher than that of patients without BSI (12.64 ± 5.59 versus 10.27 ± 5.66, respectively [P < 0.001]). Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of patients and controls according to the severity of the episode.

TABLE 3.

Patient characteristics and comparison of clinical and epidemiological variables between patients and controls

| Characteristic | Value

|

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 601) | Patients (n = 298) | Controls (n = 303) | ||

| Mean age ± SD (yr) | 59.8 ± 17.3 | 62.7 ± 16.8 | 56.8 ± 17.3 | <0.001 |

| Sex (% male) | 63.9 | 64.8 | 63.0 | 0.646 |

| Department (%) | 0.069 | |||

| Medical | 43.4 | 46.3 | 40.6 | |

| Surgical | 22.1 | 23.11 | 21.1 | |

| Intensive care unit | 18.0 | 17.6 | 18.5 | |

| Hematology-oncology | 11.1 | 10.4 | 11.9 | |

| Other | 5.1 | 2.6 | 7.9 | |

| McCabe-Jackson scale (%) | 0.983 | |||

| Type I | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.3 | |

| Type II | 39.5 | 39.7 | 39.3 | |

| Type III | 53.1 | 52.8 | 53.5 | |

| Underlying illness (%) | ||||

| Cardiopathy | 24.9 | 27.7 | 22.1 | 0.113 |

| Broncopathy | 24.4 | 26.7 | 22.1 | 0.189 |

| Ulcer | 17.5 | 19.2 | 15.8 | 0.288 |

| Diabetes | 20.5 | 26.7 | 14.2 | <0.001 |

| Neoplasia | 18.0 | 19.9 | 16.2 | 0.248 |

| Charlson's comorbidity score (mean ± SD) | 3.5 ± 2.4 | 3.7 ± 2.4 | 3.2 ± 2.3 | 0.016 |

| Other characteristics and treatments (%) | ||||

| Hypoproteinemia | 34.6 | 34.2 | 35.0 | 0.865 |

| Intravenous drug abuse | 2.8 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 0.138 |

| Neutropenia | 5.4 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 0.595 |

| Splenectomy | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.000 |

| Radiotherapy | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.06 | 0.601 |

| Chemotherapy | 15.2 | 13.4 | 17.2 | 0.216 |

| Corticosteroids | 18.5 | 18.6 | 18.5 | 1.000 |

| Prior surgery | 27.4 | 23.8 | 31.0 | 0.046 |

| Invasive procedures | 47.4 | 45.3 | 49.9 | 0.331 |

| Prosthetic material | 20.0 | 23.1 | 16.8 | 0.055 |

| Intravenous line | 69.3 | 62.9 | 75.9 | <0.001 |

| Bladder catheter | 32.5 | 31.6 | 33.3 | 0.666 |

| Skin lesions | 7.0 | 11.1 | 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Prior antimicrobials | 44.1 | 30.9 | 57.4 | <0.001 |

| APACHE II score (mean ± SD) | 11.5 ± 5.7 | 12.6 ± 5.6 | 10.3 ± 5.7 | <0.001 |

FIG. 2.

Distribution of patients with positive and negative blood cultures according to the APACHE II index.

By multivariate analyses, the independent predictors of bacteremia/fungemia were higher age (OR, 1.011; 95% CI, 1 to 1.023; P, 0.04), Apache II index at the onset of disease (OR, 1.071; 95% CI, 1.035 to 1.107; P, <0.001), the presence of diabetes mellitus (OR, 2.273; 95% CI, 1.457 to 3.545; P, <0.001), and the absence of antibiotic therapy at onset (OR, −0.281; 95% CI, 0.197 to 0.402; P, <0.001). The model did not show the volume of blood cultured to be an independent variable affecting blood culture results.

The risk factors for obtaining low-volume specimens (<30 ml of blood cultured per episode) were higher age (OR, 1.015; 95% CI, 1.005 to 1.03; P, 0.005) and higher Apache II score (OR, 1.044; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.08; P, 0.008).

Stratification of patients according to severity.

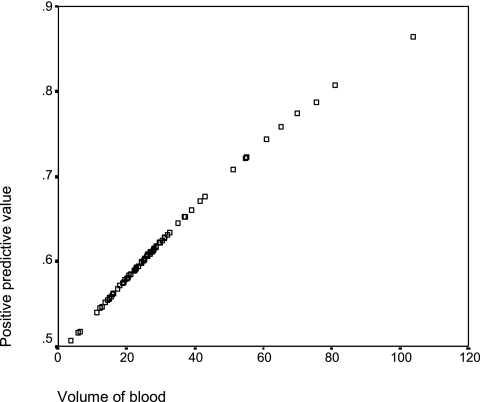

The population was stratified according to Apache II scoring, and the positive predicted value of blood volume was studied again with a multivariate analysis. In the subgroup of patients with an APACHE II score of <18, volume was again excluded from the model as an independent predictor factor of positive blood cultures. In the subgroup of patients with an Apache II score of >18 (54 patients and 34 controls), the variable of volume was retained in the model and higher volumes were associated with better yields of detection of BSI. In the latter group, the detection rate increased by 3.7% for each extra milliliter of blood cultured (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.001 to 1.08). Figure 3 shows the positive predictive value in relation to the volume of blood cultured.

FIG. 3.

Relationship between volume of blood and probability of bacteremia/fungemia, after patients were stratified according to the severity of their clinical condition, in the subgroup of patients with an APACHE II score of >18 (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.001 to 1.08).

Mean volume of blood processed per blood culture.

Finally, we investigated the yield of sample volume per blood culture (a set of two bottles, one aerobic and one anaerobic, inoculated with blood from a single puncture) rather than per patient (whole blood sample obtained per episode), as was done previously. We considered only the patients with confirmed BSI and investigated the yield of positive and negative blood culture sets from these patients. The mean volume of the positive blood sets was 10.04 ± 6.09 ml, and the mean volume of the negative blood sets was 9.1 ± 5.7 ml (P, 0.05; 95% CI, −1.879 to 0.001).

By multivariate analysis, higher blood volumes were associated with positive blood culture sets independently of other variables studied. The increase in the detection rate of BSI was 3.3% for each extra milliliter of blood cultured (OR, 1.03, 95% CI, 1.002 to 1.07; P, 0.04).

The average detection time of growth was 13.55 h (range, 0.66 to 89.02 h) regardless of the blood volume being cultured (Pearson's correlation, 0.095; P, 0.181).

DISCUSSION

Our work demonstrates that the lower volumes of blood cultured from patients with bacteremia are consequences only of the severity of the conditions under which the blood cultures are drawn. When clinical variables are considered, the higher the volume of blood cultures, the higher the yield of detection of BSI.

It is classically accepted that the yield of blood cultures from adults is clearly volume dependent (1, 7, 12, 16, 23). It is considered that the extra yield obtained with a greater volume (an increase of 3% to 5% in the detection rate with each additional milliliter of blood) is due to the fact that most BSI episodes in adults have a low density of microorganisms in blood (average, 1 CFU/ml) (4, 8, 10, 19).

The volume recommended by the American Society for Microbiology is between 10 and 30 ml per blood culture (5). This recommendation is based on observations mostly made more than 30 years ago, before the existence of automated blood culture systems. However, obtaining this volume of blood, as recommended by the American Society for Microbiology, is often very difficult in clinical practice and increases the risk of nosocomial anemia. Thus, it was very important to reassess whether such high volumes are still needed when the new blood culture systems are used.

Reports concerning the importance of the volume of blood cultured with the new continuous-monitoring blood culture systems are scarce. Weinstein et al. (1994), using the BacT/Alert system (Organon Teknika Corp, Durham, NC), compared the yield and speed of detection of microorganisms in aerobic bottles inoculated with 5 and with 10 ml of blood. The overall recovery of microorganisms from 10-ml samples exceeded that from 5-ml samples (P < 0.001). The increased yield from the 10-ml inocula was mostly marked for Enterobacteriaceae (P < 0.001) but not so for gram-positive bacteria, nonfermentative gram-negative rods, or yeasts (24).

In our study, we investigated the value of blood volume obtained per episode of sepsis and its relationship with the detection of BSI. We found that the independent predictors of BSI were higher age, higher severity of the patients' condition (APACHE II score), diabetes mellitus, and the absence of antimicrobials at the moment the blood cultures were drawn. Of note, these variables predicted the presence of bacteremia regardless of the blood volume that was cultured per episode.

However, it turned out that higher age and severity of condition were significantly associated with lower volumes, and the volume was finally found to be a confounding variable linked to the severity of the underlying condition.

When we stratified the population according to the severity of illness, we observed that in the subgroup of patients with a higher Apache II score (the more likely to have BSI), the higher the volume obtained, the larger the number of episodes of BSI detected, and that the yield of detection increased by around 3.5% with each additional milliliter of blood cultured.

The increased yield of 3.5% is in accord with previous reports (range, 0.6% to 4.7%) (2, 7, 9, 15, 16, 18, 20). Mermel and Maki found an increased yield of 3.2% in their study (15). Mensa et al., in a study using a methodology similar to ours but with the BACTEC NR-860 system (Becton-Dickinson), found an increased yield of 2.28% per milliliter of blood cultured (14).

If the yield increases with each additional milliliter of blood, what then is the ideal volume to be cultured with the new blood culture systems? In our view, there is not yet enough data in the literature to give a definitive answer to this question.

Classically, the ideal bottle inoculum for each blood culture system has been determined by large controlled studies performed in microbiology laboratories; however, we believe that clinical judgment on how much blood should be drawn for an individual patient could be also based on studies that analyze the risk factors for bacteremia and the probability of obtaining a positive blood culture under different clinical situations, with, for example, the severity of the clinical condition taken into account.

As proposed by Mermel and Maki, it is possible that few clinicians or nurses are actually aware of the powerful influence that the volume of blood has on the sensitivity of blood cultures for detecting bacteremia and fungemia in adult patients (15). Moreover, according to our results, emphasis should be placed on getting higher volumes, especially from severely ill patients, for whom sample collection is more difficult and official recommendations are not always fulfilled.

However, we should also note that drawing large volumes of blood from patients who are at low risk for bacteremia, by escalating (for example) the number of repeated sets of blood cultures per episode of sepsis, unnecessarily increases the proportion of false-positive results and contributes to iatrogenic anemia without improving the rate of detection of BSI.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that, with the BACTEC 9240 system and BACTEC Aerobic Plus and Anaerobic Plus bottles, the blood volume cultured is a variable that influences the blood culture yield. The lower volume of blood introduced into blood bottles from patients with more-severe disease is a consequence of the difficulty of drawing blood from such patients.

We believe that the blood volume drawn should reflect a balance between the need for a microbiological diagnosis and the risk for the patients of acquiring nosocomial anemia. The higher yield of blood cultures inoculated with lower volumes of blood reflects the condition of the population being cultured. Washington's dictum holds true today.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Public Health Service grant CIBER-CB06/06/0058.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson, M. D., and D. H. Bor. 1987. Blood cultures. Ann. Intern. Med. 106:246-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown, D. F. J., and R. E. Warren. 1990. Effect of sample volume on yield of positive blood cultures from adult patients with hematological malignancy. J. Clin. Pathol. 43:777-779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charlson, M. E., P. Pompei, K. L. Ales, and C. R. McKenzie. 1987. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal populations: development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 40:373-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorn, G. L., G. G. Burson, and J. R. Haynes. 1976. Blood culture technique based on centrifugation: clinical evaluation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 3:258-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunne, J., F. Nolte, and M. Wilson. 1997. Blood cultures III. In J. Hindler (ed.), Cumitech 1B. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 6.Eyster, E., and J. Bernene. 1973. Nosocomial anemia. JAMA 223:73-74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall, M. M., D. M. Ilstrup, and J. A. Washington II. 1976. Effect of volume of blood cultured on detection of bacteremia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 3:643-645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henry, N. K., C. A. McLimans, A. J. Wright, R. L. Thompson, W. R. Wilson, and J. A. Washington II. 1983. Microbiological and clinical evaluation of the isolator lysis-centrifugation blood culture tube. J. Clin. Microbiol. 17:864-869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ilstrup, D. M., and J. A. Washington II. 1983. The importance of volume of blood cultured in the detection of bacteremia and fungemia. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1:107-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellogg, J. A., J. P. Manzella, and J. H. McConville. 1984. Clinical laboratory comparison of the 10-ml isolator blood culture system with BACTEC radiometric blood culture media. J. Clin. Microbiol. 20:618-623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knaus, W. A., E. A. Draper, D. P. Wagner, and J. E. Zimmerman. 1985. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit. Care Med. 13:881-892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li, J., J. J. Plorde, and L. G. Carlson. 1994. Effects of volume and periodicity on blood cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2829-2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCabe, W. R., and G. G. Jackson. 1962. Gram-negative bacteremia. Arch. Intern. Med. 110:847-855. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mensa, J., M. Almela, C. Casals, J. A. Martínez, F. Marco, R. Tomás, F. Vidal, E. Soriano, and T. Jiménez de Anta. 1997. Yield of blood cultures in relation to the cultured blood volume in Bactec 6A bottles. Med. Clin. (Barcelona) 108:521-523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mermel, L. A., and D. G. Maki. 1993. Detection of bacteremia in adults: consequences of culturing an inadequate volume of blood. Ann. Intern. Med. 119:270-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plorde, J. J., F. C. Tenover, and L. G. Carlson. 1985. Specimen volume versus yield in the BACTEC blood culture system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 22:292-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Créixems, M., E. Bouza, J. Guinea, C. Fron, P. Munoz, and C. Sánchez. 1999. Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 208.

- 18.Sandven, P., and E. A. Hoiby. 1981. The importance of blood volume cultured on detection of bacteraemia. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 89:149-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarrand, J. J., C. Guillot, M. Wenglar, J. Jackson, J. D. Lajeunesse, and K. V. Rolston. 1991. Clinical comparison of the resin-containing BACTEC 26 Plus and the Isolator 10 blood culturing systems. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:2245-2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tenney, J. H., L. B. Reller, S. Mirrett, W. L. Wang, and M. P. Weinstein. 1982. Controlled evaluation of the volume of blood cultured in detection of bacteremia and fungemia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 15:558-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Washington, J. A. 1975. Blood cultures: principles and techniques. Mayo Clin. Proc. 50:91-95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Washington, J. A. 1993. Evolving concepts on the laboratory diagnosis of septicemia. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pract. 2:65-69. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Washington, J. A., II, and D. M. Ilstrup. 1986. Blood cultures: issues and controversies. Rev. Infect. Dis. 8:792-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinstein, M. P., S. Mirrett, M. L. Wilson, L. G. Reimer, and L. B. Reller. 1994. Controlled evaluation of 5 versus 10 milliliters of blood cultured in aerobic BacT/Alert blood culture bottles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2103-2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]