Abstract

Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium hominis isolates from sporadic, drinking water-associated, and intrafamilial human cases together with C. parvum isolates from sporadic cases in livestock were collected in the United Kingdom between 1995 and 1999. The isolates were characterized by analysis of three microsatellite markers (ML1, GP15, and MS5) using PCR amplification. Within C. hominis, four alleles were detected within the GP15 and MS5 loci, and a single type was detected with ML1. C. parvum was more polymorphic; 12 alleles were detected with GP15, 6 were detected with MS5, and 3 were detected with ML1. Multilocus analysis of polymorphisms within the three microsatellite loci was combined with those reported previously for an extrachromosomal small double-stranded RNA. Forty multilocus types were detected within these two species: 9 were detected in C. hominis, and 31 were detected in C. parvum. In C. hominis, heterogeneity was almost exclusively found in samples from sporadic cases. Similarity analysis identified three main groups within C. parvum, and the group that predominated in human infection was also found in livestock. Multilocus types of C. parvum previously identified only in humans were not detected in livestock. Isolates of both C. hominis and C. parvum from separate waterborne outbreaks were genetically homogeneous, suggesting preferential or point source transmission of certain types of these two species of parasites.

Cryptosporidium is a protozoan parasite that causes gastrointestinal disease in a wide range of vertebrates, including humans. The sporulated oocyst is the transmissive stage and is immediately infectious when excreted in feces (10). Zoonotic and nonzoonotic transmissions occur by the fecal-oral route following either direct contact with contaminated feces from an infected host or indirectly via environmentally contaminated sources including drinking water, foods, beverages, and the ingestion of oocyst-contaminated bathing waters (11, 24). The characteristics of a low infectious dose, prolonged environmental survival, and insensitivity to disinfectants facilitate transmission (8). Contact with other cases, foreign travel, consumption of contaminated drinking water, and contact with livestock are recognized risk factors for human cryptosporidiosis (15).

Molecular analysis of Cryptosporidium has revealed the complexity of the genus and identified distinct species whose oocysts are morphologically indistinguishable (36). The genus Cryptosporidium contains at least 16 species that exhibit differences in host range and numerous genotypes, some of which may be covert species (36).

Cryptosporidium hominis and Cryptosporidium parvum are the major species responsible for human disease (17, 36). C. hominis (25) is primarily a human pathogen, although it has been detected infrequently in other primates (32), a marine mammal (26), and cattle (29), whereas C. parvum has a broad host range including humans and livestock (8).

Molecular methods to subgenotype C. parvum and C. hominis are required to understand the epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis, identify reservoirs of infections, and track this group of organisms in the environment (8, 30). Genetic polymorphisms within C. parvum and C. hominis have been identified among human and nonhuman isolates using a single-locus analysis of the gp15/45/60 glycoprotein gene (33), an extrachromosomal linear virus-like double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) (16), and multilocus analysis of mini- and microsatellite loci (7, 12). The gp15/45/60 gene has a high degree of sequence polymorphism, which enables different C. parvum and C. hominis allelic subgroups to be identified (28). Mini- and microsatellite analysis using seven markers, one of which is a microsatellite region (locus GP15) in the gp15/45/60 gene (19, 20), identified five distinct C. parvum groups in humans and livestock, two of which were restricted to humans (20). The gp15/45/60 locus was used to survey Cryptosporidium oocysts in raw wastewater from Milwaukee and enabled the identification of different allelic subgroups of C. hominis and C. parvum (37). A single C. hominis subgroup predominated (37), which was identical to that found in a single case from the 1993 waterborne outbreak (34) and was also present in other waterborne outbreaks in the United States, Ireland, and France (9, 13, 34). A drinking water-associated outbreak in Glasgow (United Kingdom) was investigated using mini- and microsatellite multilocus genotyping (MLG) (31). Of 46 C. parvum outbreak samples, five MLG types (types 6, 7, 9, 23, and 59) were identified. Parasites in the majority of outbreak cases (71%) were MLG-6, and its epidemic curve closely followed the outbreak epidemic curve. MLG-6 is common in cattle and was the major MLG responsible for the outbreak. Comparison with 26 background cases that occurred at the same time in Glasgow, but which were not considered to be part of the outbreak, indicated that MLG-10 and -34 were predominant (31). Hence, there are relatively few studies characterizing Cryptosporidium isolates from outbreaks using polymorphic markers.

A 173-bp fragment of the extrachromosomal linear small dsRNA of Cryptosporidium was used to characterize a group of isolates collected from cases of human sporadic, waterborne, and intrafamilial outbreaks and livestock outbreaks in the United Kingdom, which revealed the presence of variants within C. hominis and C. parvum isolates (18).

By combining approaches based on different nucleic acid fingerprinting strategies, increased discrimination beyond that attainable with individual approaches may be obtained, thus providing a clearer understanding of the molecular epidemiology of C. hominis and C. parvum cryptosporidiosis in human and nonhuman hosts.

The aim of this study was to present data on the further characterization of genetic polymorphisms exhibited among a group of isolates previously analyzed using the dsRNA approach (18) using three microsatellite loci, including the highly polymorphic GP15 locus. The isolates consisted of epidemiologically related C. parvum and C. hominis isolates from human cryptosporidiosis cases, sporadic human C. parvum and C. hominis cases, and C. parvum isolates from sporadic cases among livestock.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fecal samples and epidemiological information.

Two hundred thirty fecal samples from humans with diarrhea and 17 from livestock (lambs or calves) were collected in the United Kingdom between 1995 and 1999 and form a subset of >2,400 previously described specimens (17, 21, 27). Cryptosporidium oocysts were detected using conventional techniques (4), and all samples were stored at 4°C as whole feces without preservatives. Brief epidemiological information was collected for all human cases, which included 5 separate outbreaks associated with contaminated drinking water (100 cases), 14 intrafamilial outbreaks (29 cases), and 101 sporadic cases (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Samples tested and epidemiological relationships

| Origin of fecal samples | No. of samples tested

|

Description | Reference(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | C. parvum | C. hominis | |||

| Human (total) | 230 | 126 | 104 | ||

| Drinking water outbreak 1 | 22 | 1 | 21 | South West England, August and September 1995, river water contamination | 6, 21, 22 |

| Drinking water outbreak 2 | 36 | 36 | North London, February and April 1997, borehole contamination | 21, 35 | |

| Drinking water outbreak 3 | 3 | 3 | North London, January and March 1997, borehole contamination | 6, 21 | |

| Drinking water outbreak 4 | 18 | 18 | North West England, April 1998, contamination of water tank by livestock feces | 2, 21 | |

| Drinking water outbreak 5 | 21 | 21 | North West England, April and May 1999, contamination of reservoir water by livestock feces | 2, 21 | |

| 14 intrafamilial outbreaks (2 or 3 patients per family group) | 29 | 13 | 16 | 11 groups from England 1998-1999; 2 groups from drinking water outbreaks 1 and 2; 2 groups from a swimming pool outbreak that occurred in South West London between October and November 1999 | 3, 18, 21, 27 |

| Sporadic cases | 101 | 73 | 28 | England 1999 | 18 |

| Livestock (13 bovine and 4 ovine) | 17 | 17 | England and Scotland 1996-1997 | 18, 21, 27 | |

Nucleic acid extraction and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis.

Nucleic acid was extracted from whole feces by a previously described (23) modification of the “Boom method” (5). A nested PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of a fragment of the cryptosporidium oocyst wall protein (COWP) gene was used to identify C. parvum and C. hominis (27).

PCR and automated fragment analysis of the ML1, GP15, and MS5 microsatellite loci.

Based upon the limited amount of material available, we tested the three most polymorphic loci used by Mallon et al. (ML1, GP15, and MS5) (19, 20) with primers and conditions described previously (7, 19). One of each primer pair was 5′ labeled with WellRED dye D4-PA (Proligo, Helena Biosciences, Tyne and Wear, United Kingdom). Microsatellite analysis of labeled fragments was performed with a CEQ 8000 genetic analysis system using a CEQ DNA Size Standard Kit 600 (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, United Kingdom). Allele sizes were identified using automated fragment analysis and the DNA size standard as well as by comparison with reference samples that had been previously characterized for microsatellite allele size (19, 20).

Sequencing and analysis of microsatellite loci.

PCR products for each microsatellite locus were amplified using unlabeled primers and purified with the StrataPrep PCR purification kit (Stratagene Europe, Amsterdam Zuidoost, The Netherlands). Sequencing analysis was performed in both directions with a CEQ 2000 Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Quick Start kit (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, United Kingdom), according to the manufacturer's instructions, using specific primers and a CEQ 8000 genetic analysis system automated capillary sequencer (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, United Kingdom). Sequences were analyzed and aligned by GeneBuilder and Clustal in Bionumerics, version 2.5 (Applied Maths, Belgium). The relationship between isolates was assessed by the unweighted-pair group method with arithmetic means. Multiple alignment analysis was performed with the BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor version 5.0.0 (14).

Multilocus analysis.

Microsatellite genotypes were combined with the previously reported genotypes determined by heteroduplex mobility (HMA) characterization of an extrachromosomal dsRNA element (18). Briefly, cDNA for the characterization of the 173-bp fragment of the small dsRNA was prepared by reverse transcription and random priming. The 173-bp fragment was then amplified from cDNA using the primer pair APBV1 and APBV2 with PCR conditions described previously (18). HMAs were performed with two reference oligonucleotides by adding 5 μl of test amplicon to 5 μl of reference strain amplicon. Controls included 10 μl of the individual reference amplicon without a test strain and mixtures of the two reference amplicons. The HMA assay was performed using a Perkin-Elmer 9600 thermocycler with an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min, followed by a cooling step to 4°C (slow annealing, 1°C/10 s). Tubes were incubated on ice for 10 min or until loaded onto the Mutation Detection Enhancement gel for vertical electrophoresis, which was performed in 0.6× Tris-borate-EDTA running buffer at a constant voltage of 300 V for approximately 3 h until the bromophenol blue dye band was within 1 cm of the bottom of the gel. Heteroduplex bands formed in the areas between the homoduplex and single-stranded DNA were used for analysis. HMA patterns were identified by comparison of heteroduplex bands to the marker and to previously characterized controls as well as by sequence analysis. HMA pattern analysis was performed using Bionumerics version 2.5 (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium).

RESULTS

Analysis of C. hominis and C. parvum isolates at ML1, GP15, and MS5.

Allele sizes of amplified microsatellite regions were identified using automated fragment analysis by comparison with reference material of a known size, which was previously characterized by senquencing analysis (19, 20). To ensure that different sizes obtained were not artificially created during the amplification process, microsatellite allele sizes in this study were assigned by performing a series of experiments in which reference material for locus ML1 (alleles 2, 3, 4, and 5), GP15 (alleles 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10), and MS5 (alleles 5, 7, 8, and 9) was tested by changing PCR conditions in repeated independent PCR assays followed by automated fragment analysis. Reference material was then included in each run of PCR and automated fragment analysis, when samples of this study were tested. Samples representative of different alleles were also reanalyzed in repeated PCR and automated fragment analysis tests.

Rarer or new alleles were retested by an independent PCR and automated fragment analysis and afterwards by PCR and sequencing analysis.

There was insufficient material to analyze all samples at all loci; therefore, priority was given to the analysis of the two most polymorphic loci (GP15 and MS5): 247 samples were analyzed at the GP15 and MS5 loci, and of these samples, 222 samples were analyzed at the ML1 locus.

Allele frequencies.

Four alleles were identified at the ML1 locus (Table 2): no polymorphisms were detected in C. hominis, while three alleles were detected in C. parvum, 89% of which were allele 5.

TABLE 2.

Microsatellite alleles identified at the ML1, GP15, and MS5 loci in C. hominis and C. parvum

| Organism and locus | Allelea | Allele size (bp) | Allelic identification in other systems

|

No. of samples with allele/no. analyzed | % Allele presence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type or allelic subgroup | Reference | |||||

| C. hominis | ||||||

| ML1 | 4 | 229 | H1 | 7 | 79/79 | 100 |

| GP15 | 10 | 366 | Ib | 33 | 100/104 | 96.1 |

| 12 | 411 | Ie | 28 | 1/104 | 1.0 | |

| 15 | NAb | 2/104 | 1.9 | |||

| 26 | 429 | 1/104 | 1.0 | |||

| MS5 | 3 | 277 | 1/103 | 1.0 | ||

| 5 | 301 | 1/103 | 1.0 | |||

| 8 | 325 | 99/103 | 96.1 | |||

| 10 | 349 | 2/103 | 1.9 | |||

| C. parvum | ||||||

| ML1 | 2 | 223 | C3 | 7 | 15/141 | 10.6 |

| 3 | 226 | C2 | 7 | 1/141 | 0.7 | |

| 5 | 238 | C1 | 7 | 125/141 | 88.7 | |

| GP15 | 3 | 327 | IId | 1 | 2/143 | 1.4 |

| 4 | 330 | IIa | 33 | 3/143 | 2.1 | |

| 5 | 333 | IIa | 33 | 47/143 | 32.9 | |

| 6 | 336 | IIa | 33 | 54/143 | 37.8 | |

| 7 | 339 | IIa | 33 | 6/143 | 4.2 | |

| 8 | 342 | IIa | 33 | 6/143 | 4.2 | |

| 9 | 345 | IIa | 33 | 3/143 | 2.1 | |

| 16 | 306 | 1/143 | 0.7 | |||

| 17c | 324 | 1/143 | 0.7 | |||

| 18 | 351 | IIa | 33 | 3/143 | 2.1 | |

| 19d | 354 | 1/143 | 0.7 | |||

| 27 | 321f | IId | 1 | 6/143 | 4.2 | |

| Mixture of alleles | 10/143 | 7.0 | ||||

| MS5 | 6 | 304 | 2/143 | 1.4 | ||

| 7 | 310 | 2/143 | 1.4 | |||

| 9 | 328 | 133/143 | 93.0 | |||

| 11e | 352 | 4/143 | 2.8 | |||

| 15 | 376f | 1/143 | 0.7 | |||

| 16 | 502f | 1/143 | 0.7 | |||

Allelic identification as defined by Mallon and colleagues (19; M. E. Mallon, unpublished data).

NA, not amplified.

C. parvum GP15 allele 17 in a mixture with C. hominis allele 10.

C. parvum GP15 allele 19 in a mixture with C. hominis allele 22.

C. parvum MS5 allele 11 in a mixture with C. parvum allele 9.

Not previously described.

Among the three microsatellites, the GP15 locus exhibited the highest number of alleles for both C. hominis and C. parvum, and 16 were detected (Table 2). Four alleles were detected in C. hominis, 96% of which were allele 10. Within C. parvum, 12 alleles were detected, 33% of which were allele 5 and 38% of which were allele 6. Mixtures of two GP15 alleles were identified in 7% of the C. parvum isolates, and a previously undescribed allele (321 bp, designated allele 27) was identified in 4% (6/143) of the samples.

Analysis at the MS5 locus identified 10 alleles (four in C. hominis and six in C. parvum) (Tables 2 and 3). Alleles 8 (96% of C. hominis isolates) and 9 (93% of C. parvum isolates) were predominant. Within C. hominis, sequencing confirmed the sizes of alleles 3, 5, and 10 and was performed for one isolate of each type and two isolates of allele 8. Two previously undescribed C. parvum alleles, designated alleles 15 (376 bp) and 16 (502 bp), were identified. Sequencing of alleles 6, 9, and 15 from one representative isolate of each confirmed the estimated sizes. It was not possible to directly sequence allele 16.

TABLE 3.

Analysis of the ML1, GP15, and MS5 microsatellite loci among C. hominis isolates from human sporadic cases and epidemiologically related groups collected in the United Kingdom between 1995 and 1999

| Microsatellite allele for ML1 | Microsatellite allele for:

|

No. of samples analyzed

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP15 | MS5 | Waterborne outbreak:

|

8 familial outbreaks | Sporadic cases | Total | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| 4 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 30 | 16 | 24 | 75 | |

| NPa | 10 | 8 | 16 | 5 | 3 | 24 | ||

| NP | 10 | NAb | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | 15 | 10 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| 4 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | 26 | 5 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Total | 21 | 36 | 3 | 16 | 28 | 104 | ||

NP, not performed.

NA, not amplified.

Comparison of GP15 sequencing with the gp15/45/60 gene allelic subgroups.

Sequencing indicated that C. hominis allele 12 was 100% identical to sequences reported previously for allelic subgroup Ie (28, 34). Sequencing of allele 27 from three C. parvum samples identified the presence of a sequence that was closely related to allelic subgroup IId (GenBank accession number AY166806) (1) but that was shorter by five TCA repeats. The three sequenced alleles differed by one or two bases. An isolate of allele 3 was similar to allelic subgroup IId (GenBank accession number AY166806) (1) but shorter by three TCA repeat units. Sequencing three allele 4 (330 bp) isolates revealed that two were identical and one differed by two bases. Alleles 8 (342 bp) (one isolate), 9 (345 bp) (one isolate), and 18 (351 bp) (two isolates, which were 100% identical) were closely related to the gp15/45/60 gene allelic subgroup IIa (GenBank accession number AF164495 or AY166804) (1, 33).

Molecular epidemiological analysis using three microsatellite loci. Human drinking water-associated outbreaks.

The same genotype of C. hominis was detected in all samples from the three drinking water-associated outbreaks caused predominantly by C. hominis contamination of river or borehole water, although not all samples amplified all loci (Table 3). Based on the GP15 allele, this corresponds to subgroup Ib (33).

More genotypes were identified in the two C. parvum drinking water-associated outbreaks (outbreaks 4 and 5) (Table 4) than in those caused by C. hominis (outbreaks 1, 2, and 3) (Table 3). In outbreak 4, all samples were the same at ML1 and MS5 (Table 4), whereas at the GP15 locus, three genotypes were detected (allele 6 in 83%, allele 7 in 11%, and allele 3 in 6% of samples) (Table 4). In outbreak 5, where amplified, the same genotypes at ML1 and MS5 were detected, whereas at the GP15 locus, three genotypes were detected in 20 of the 21 samples tested (allele 5 in 29%, allele 6 in 57%, and allele 8 in 10% of samples) (Table 4). The remaining sample generated a mixture of alleles 5 and 6 (Table 4). The human C. parvum drinking water-associated outbreaks, based on the GP15 alleles, belonged predominantly to allelic subgroup IIa (34).

TABLE 4.

Analysis of the ML1, GP15, and MS5 microsatellite loci among C. parvum isolates from human sporadic and epidemiologically related cases and livestock collected in the United Kingdom between 1997 and 1999

| Microsatellite allele for ML1a | Microsatellite allele for:

|

No. of samples analyzed

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waterborne outbreak:

|

6 familial outbreaks | Sporadic cases | Livestock | Total | |||||

| GP15 | MS5 | 2 | 4 | 5 | |||||

| 2b | 3 | 15 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2b | 4 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2b | 4 | 7 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2b | 5 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| 2b | 6 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2b | 16 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2b | 17-10 | 6 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2b | 27 | 7 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2b | 27 | 9 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| 2b | 27 | 16 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 3c | 5 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 5d | 3 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 5d | 4 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 5d | 5 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 24 | 7 | 43 | ||

| 5d | 6 | 9 | 1 | 15 | 11 | 2 | 20 | 3 | 52 |

| NAe | 6 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 5d | 5-6 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 5d | 5-6 | 9-11 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| 5d | 5-7 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 5d | 6-9 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 5d | 6-7 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 5d | 7 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 | |||

| 5d | 8 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 6 | ||||

| 5d | 9 | 9 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| 5d | 18 | 9 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| NA | 18 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 5d | 19-22 | 6 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Total | 1 | 18 | 21 | 13 | 73 | 17 | 143 | ||

Alleles 2, 3, and 5 of the ML1 microsatellite locus correspond to types C3, C2, and C1 as described previously by Cacciò; et al. (7).

Microsatellite allelic combinations of ML1, GP15, and MS5 that grouped with human-specific subgroup C described previously by Mallon et al. (20).

Microsatellite allelic combinations of ML1, GP15, and MS5 that grouped with human-specific subgroup A described previously by Mallon et al. (20).

Microsatellite allelic combinations of ML1, GP15, and MS5 that grouped with subgroup B described previously by Mallon et al. (20).

NA, not amplified.

Intrafamilial outbreaks.

For all outbreaks, different members within the same family had the same allele at each locus analyzed. Among C. hominis isolates from outbreaks, the same allele was identified at all three loci tested (Table 3). Greater variability was detected in C. parvum isolates from the six outbreaks; two alleles were detected at ML1 (allele 5 in five familial groups and allele 2 in the remaining group), and three alleles were detected at GP15 (alleles 5 and 6 in four groups and one group, respectively, with each group having two members, and allele 7 in the three members of the remaining group) (Table 4). No variability was detected at MS5 (Table 4).

Sporadic cases.

Microsatellite analysis was performed on material from 101 human sporadic cryptosporidiosis cases occurring in England in 1999: 28 were due to C. hominis, and 73 were due to C. parvum. A greater number of C. hominis genotypes occurred in sporadic cases than in outbreak cases (Table 3). At ML1, allele 4 was amplified from all isolates, whereas four alleles were present at the GP15 and MS5 loci (with alleles 10 and 8 being the most common at the GP15 and MS5 loci, respectively) (Table 4). The two samples that did not generate a product at GP15 both yielded allele 10 at the MS5 locus and allele 4 at the ML1 locus; therefore, to maintain the established allelic numbering system described previously by Mallon et al. (19, 20), they were classified as allele 15. Two of the C. hominis isolates from sporadic cases were identified from recent foreign travel (Sudan and Pakistan) and generated genotypes that were not detected in any of the other samples tested (alleles 12 and 26 at GP15 and alleles 3 and 5 at MS5) (Table 3).

Analysis of the 73 sporadic C. parvum cases revealed a greater number of genotypes than did the C. parvum outbreak samples (Table 4). At ML1 and MS5, alleles 5 (80%) and 9 (92%), respectively, accounted for the majority of infections, whereas at GP15, alleles 5 and 6 were the most common alleles (36% and 29% of isolates, respectively) (Table 5). A previously undescribed allele, designated allele 27, was found in 8% (6/73) of cases. Mixed infections of C. parvum and C. hominis or of different C. parvum genotypes were identified in 6% (4/73) of cases (Table 4).

TABLE 5.

MLTs among C. hominis and C. parvum isolates obtained by combining results from analysis of microsatellite loci (ML1, GP15, and MS5) and the small dsRNA (HMA type)

| MLT | Microsatellite allele for:

|

dsRNA HMA type | No. of samples of:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML1 | GP15 | MS5 | C. hominis | C. parvum from humans | C. parvum from livestock | ||

| 1 | 4 | 10 | 8 | CPV1-1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 4 | 10 | 8 | CPV1-2 | 66 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 4 | 10 | 8 | CPV1-3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 4 | 10 | 8 | CPV1-4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 4 | 15 | 10 | CPV1-5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 4 | 12 | 3 | CPV1-6 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 4 | 10 | 8 | CPV1-7 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 4 | 26 | 5 | CPV1-8 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 4 | 10 | 8 | CPV1-9 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 5 | 5 | 9 | CPV2-1 | 0 | 26 | 11 |

| 11 | 5 | 6 | 9 | CPV2-1 | 0 | 34 | 5 |

| 12 | 5 | 7 | 9 | CPV2-1 | 0 | 7 | 1 |

| 13 | 5 | 8 | 9 | CPV2-1 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| 14 | 5 | 9 | 9 | CPV2-1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 15 | 5 | 18 | 9 | CPV2-1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 16 | 5 | 3 | 9 | CPV2-1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 17 | 5 | 19 | 6 | CPV2-1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 18 | 2 | 6 | 9 | CPV2-1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 19 | 2 | 3 | 15 | CPV2-1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 20 | 2 | 27 | 9 | CPV2-1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 21 | 3 | 5 | 9 | CPV2-1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 22 | 5 | 4 | 9 | CPV2-2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 23 | 5 | 5 | 9 | CPV2-2 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| 24 | 5 | 6 | 9 | CPV2-2 | 0 | 15 | 0 |

| 25 | 2 | 27 | 9 | CPV2-3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 26 | 2 | 4 | 7 | CPV2-4 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 27 | 2 | 27 | 16 | CPV2-5 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 28 | 2 | 17 | 6 | CPV2-5 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 29 | 2 | 16 | 9 | CPV2-6 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 30 | 5 | 8 | 9 | CPV2-7 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 31 | 5 | 6 | 9 | CPV2-7 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 32 | 2 | 27 | 9 | CPV2-8 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 33 | 5 | 9 | 9 | CPV2-9 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 34 | 2 | 27 | 9 | CPV2-9 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 35 | 2 | 27 | 7 | CPV2-10 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 36 | 2 | 5 | 9 | CPV2-10 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 37 | 5 | 5 | 9 | CPV2-11 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 38 | 2 | 4 | 9 | CPV2-12 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 39 | 5 | 5 | 9 | CPV2-12 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 40 | 2 | 5 | 9 | CPV2-13 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 78 | 124 | 17 | ||||

Livestock.

Seventeen samples of C. parvum from cases of naturally occurring sporadic diarrhea in 13 calves and four lambs from Scotland and England were tested. At the ML1 locus, all 17 samples were the same (Table 4). Three alleles were identified at the GP15 locus (allele 5 in 41% of samples and allele 6 in 18% of samples). A mixture of two alleles was detected in the remaining samples (41%). At locus MS5, allele 9 accounted for 77% of samples, and the remainder (24%) contained mixtures of two alleles.

All four ovine samples had the same alleles at all loci, and the presence of more than one allele at the GP15 (alleles 5 and 6) and MS5 (alleles 9 and 11) loci provided evidence of mixed-genotype C. parvum infections.

MLTs combining data from ML1, GP15, and MS5 analysis and the small dsRNA element of Cryptosporidium.

The multilocus type (MLT) was determined for all samples on the basis of the allelic combination at the three microsatellite loci in combination with the above-described HMA type of the small dsRNA element. Overall, 40 MLTs were identified: 9 in C. hominis and 31 in C. parvum (Table 5).

Among C. hominis isolates, seven of the nine MLTs were identified in the samples from sporadic cases (Fig. 1a). One MLT, MLT2, was predominant among waterborne and intrafamilial outbreaks as well as from sporadic cases. A second MLT, MLT7, was found in only one sample from a waterborne outbreak. MLTs 6 and 8 were also unique and were identified in isolates from two patients with a recent history of foreign travel to the Sudan and Pakistan, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Frequency of MLTs among C. hominis and C. parvum isolates from waterborne outbreaks (drinking water), intrafamilial outbreaks, and sporadic cases of human cryptosporidiosis.

Among the C. parvum isolates, three and seven different MLTs were identified in waterborne outbreaks 4 and 5, respectively (Fig. 1b). MLT11 was predominant in waterborne outbreak 4 and occurred equally with MLT10 in outbreak 5. The six intrafamilial outbreaks contained five MLTs: MLT10 was identified in two of these groups.

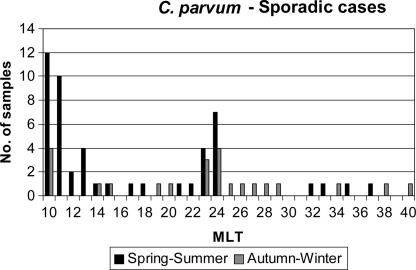

MLTs 10, 24, and 11 were the most common among the sporadic human cases, and of these, MLTs 10 and 11 were also the most common in livestock (Table 5). The distribution of MLTs in the samples collected in 1999 from sporadic human C. parvum cases was also analyzed in relation to cases occurring in April to June or October to December. This analysis showed that different MLTs occurred at different times of the year. For example, the major contributors to human sporadic cases throughout the year were MLTs 10, 23, and 24, whereas MLT11 caused human disease in the spring and summer. Some MLTs were present only in the periods of spring to summer or autumn to winter (Fig. 2). There were no differences detected in the distribution of MLTs between samples collected from different geographical areas (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Distribution of MLTs in sporadic human cases in England due to C. parvum in the spring/summer (April to June) and autumn/winter (October to December) peaks of 1999.

DISCUSSION

Microsatellite loci exhibit polymorphism in the number of repeats, which makes them ideal markers for molecular epidemiological investigations. This study used mini- and microsatellite analysis of Cryptosporidium isolates from livestock and human cases from different epidemiological groups, including waterborne outbreaks, intrafamilial outbreaks, and sporadic cases. Mallon et al. (19, 20) previously evaluated seven mini- and microsatellite loci, but the small amount of sample that remained after previous analyses (17, 18, 27) was insufficient for us to analyze all seven loci. As we had used these samples to type and subtype C. parvum and C. hominis previously, we felt it important to retest them so that microsatellite subtyping data could also be incorporated and analyzed in conjunction with data already available for these samples. Therefore, we selected those loci (ML1, GP15, and MS5) that had the greatest variation (19, 20). Our analysis relied primarily on the direct sizing of microsatellites and not on DNA sequencing. Although the former approach is easier to apply to larger numbers of samples, it will not identify some of the variation present. Since similar results for the parasite population homogeneity in outbreaks (see below) have been obtained here using a reduced set of alleles (including an independent marker, the dsRNA element), together with those described previously using DNA sequences, these approaches appear to be comparable.

Microsatellite polymorphisms at three separate loci were combined with analysis of an extrachromosomal marker, the small dsRNA, which also exhibits intra- and interspecies variability (18). When data from the microsatellites and the small dsRNA element were combined, 40 MLTs were generated: 9 within C. hominis and 31 within C. parvum. Heterogeneity was consistently greater in both species of Cryptosporidium from sporadic cases. The nine C. hominis types identified by HMA analysis of the dsRNA correspond to four allelic combinations of the ML1, GP15, and MS5 microsatellite loci.

Sequence analysis of HMA types CPV1-5, CPV1-6, and CPV1-8 clustered these types within a more divergent group of C. hominis isolates (18). Microsatellite analysis at the GP15 and MS5 loci detected further polymorphism in this group, confirming previously reported results (18). Combined analysis of the microsatellite and dsRNA indicated that the latter was the more variable marker for C. hominis. However, C. parvum microsatellite analysis further subdivided the same HMA type into more than one MLT, principally by variation at the GP15 locus (Table 5). In addition, samples that had the same allelic combination at the three microsatellite loci were differentiated by dsRNA HMA types, indicating that the MLT approach was the most effective approach for detecting diversity within C. parvum.

The general conclusions of this study reconfirm previous observations using an increased number of loci (7, 19, 20) that (i) genotypes within C. hominis and C. parvum are exclusive to each of these two species and these parasites occur as independent populations, (ii) C. parvum is considerably more genetically heterogeneous than C. hominis (19), and (iii) our MLT analysis extends the nonoverlapping genotypes found in C. hominis and C. parvum. In addition, this study presents novel observations on the distribution of MLTs within these two species, suggesting preferential transmission (especially during waterborne outbreaks) of specific variants of both C. hominis and C. parvum.

For C. hominis, analysis of both the microsatellite and MLTs indicates that the majority of the diversity occurs in the sporadic cases, with the outbreaks being almost exclusively a single MLT. This is in agreement with data reported previously by others (19) and may suggest that there is a single highly virulent and/or environmentally robust genotype that is preferentially transmitted. In addition, the increased diversity in sporadic cases indicates that there is a series of (possibly less virulent) genotypes circulating in the symptomatic human population. It would be interesting to analyze samples from asymptomatic individuals with C. hominis infection, as the level of diversity might be greater if this group had been sampled.

Within C. parvum, the microsatellite and MLT data described here support those described previously by Mallon et al. (19) in that a much greater number of genotypes exist than within C. hominis. In addition, there is generally a greater diversity within C. parvum than within C. hominis waterborne or familial outbreaks. MLTs show that sporadic cases appear to be diverse, suggesting many independent origins of infection.

A degree of host substructuring within C. parvum populations has been reported previously, whereby parasites that infected humans could be subdivided into three subgroups, two of which (subgroups A and C) were found only in humans, whereas subgroup B, which accounted for the majority of infections, was also found in cattle and sheep (Table 4) (20). Based on three of the seven microsatellite loci used previously (20), we also agree that the majority of human C. parvum infections were caused by parasites that also infect livestock. This group contained the most common C. parvum MLTs identified in this study, and the majority were of types of subgroup B (20). We did not detect MLTs of subgroups A and C in our small number of livestock isolates.

Domestic livestock represents a major reservoir of human infection by C. parvum, yet our C. parvum isolates from humans appear to be more variable than those from livestock. MLT analysis revealed heterogeneity in both sporadic and outbreak-related C. parvum isolates, which is likely to reflect a highly complex population structure within this species.

Future work to investigate specific C. parvum transmission cycles should focus on characterizing polymorphic markers from a larger number of human and livestock isolates collected from diverse geographical regions and hosts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank colleagues in clinical and veterinary microbiology laboratories for donating specimens and collecting epidemiological data.

The financial support from the Leverhulme Trust for the work from the Glasgow laboratory is acknowledged.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 August 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alves, M., L. Xiao, I. Sulaiman, A. A. Lal, O. Matos, and F. Antunes. 2003. Subgenotype analysis of Cryptosporidium isolates from humans, cattle, and zoo ruminants in Portugal. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2744-2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. 1999. Surveillance of waterborne disease and water quality. January to June 1999, and summary 1998. Public Health Lab. Serv. Commun. Dis. Rep. 9:305-308. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. 2000. Surveillance of waterborne disease and water quality: July to December 1999. Public Health Lab. Serv. Commun. Dis. Rep. 10:65-68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arrowood, M. J. 1997. Diagnosis, p. 43-64. In R. Fayer (ed.), Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL.

- 5.Boom, R., C. J. A. Sol, M. M. M. Salimans, C. L. Jansen, P. M. E. Wertheim-van Dillen, and J. Van der Noordaa. 1990. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:495-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouchier, I. 1998. Cryptosporidium in water supplies: third report of the group of experts. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, United Kingdom.

- 7.Cacciò, S., W. Homan, R. Camilli, G. Traldi, T. Kortbeek, and E. Pozio. 2000. A microsatellite marker reveals population heterogeneity within human and animal genotypes of Cryptosporidium parvum. Parasitolology 120:237-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cacciò, S. M., R. C. A. Thompson, J. McLauchlin, and H. V. Smith. 2005. Unravelling Cryptosporidium and Giardia epidemiology. Trends Parasitol. 21:430-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen, S., F. Dalle, A. Gallay, M. Di Palma, A. Bonnin, and H. D. Ward. 2006. Identification of Cpgp40/15 type Ib as the predominant allele in isolates of Cryptosporidium spp. from a waterborne outbreak of gastroenteritis in South Burgundy, France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:589-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fayer, R. 2004. Cryptosporidium: a water-borne zoonotic parasite. Vet. Parasitol. 126:37-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fayer, R., U. Morgan, and S. J. Upton. 2000. Epidemiology of Cryptosporidium: transmission, detection, and identification. Int. J. Parasitol. 30:1305-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng, X., S. M. Rich, D. Akiyoshi, J. K. Tumwine, A. Kekintiinwa, N. Nabukeera, S. Tzipori, and G. Widmer. 2000. Extensive polymorphism in Cryptosporidium parvum identified by multilocus microsatellite analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3344-3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaberman, S., J. E. Moore, C. J. Lowery, R. M. Chalmers, I. Sulaiman, K. Elwin, P. J. Rooney, B. C. Millar, J. S. Dooley, A. A. Lal, and L. Xiao. 2002. Three drinking-water-associated cryptosporidiosis outbreaks, Northern Ireland. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:631-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall, T. A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41:95-98. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter, P. R., and R. C. A. Thompson. 2005. The zoonotic transmission of Giardia and Cryptosporidium. Int. J. Parasitol. 35:1181-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khramtsov, N. V., P. A. Chung, C. C. Dykstra, J. K. Griffiths, U. M. Morgan, M. J. Arrowood, and S. J. Upton. 2000. Presence of double-stranded RNAs in human and calf isolates of Cryptosporidium parvum. J. Parasitol. 86:275-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leoni, F., C. F. L. Amar, G. Nichols, S. Pedraza-Díaz, and J. McLauchlin. 2006. Genetic analysis of Cryptosporidium from 2414 humans with diarrhoea in England 1985-2001. J. Med. Microbiol. 55:703-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leoni, F., C. I. Gallimore, J. Green, and J. McLauchlin. 2003. Molecular epidemiological analysis of Cryptosporidium isolates from humans and animals by using a heteroduplex mobility assay and nucleic acid sequencing based on a small double-stranded RNA element. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:981-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mallon, M., A. MacLeod, J. Wastling, H. Smith, B. Reilly, and A. Tait. 2003. Population structures and the role of genetic exchange in the zoonotic pathogen Cryptosporidium parvum. J. Mol. Evol. 56:407-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mallon, M. E., A. MacLeod, J. M. Wastling, H. Smith, and A. Tait. 2003. Multilocus genotyping of Cryptosporidium parvum type 2: population genetics and structuring. Infect. Genet. Evol. 3:207-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLauchlin, J., C. Amar, S. Pedraza-Díaz, and G. L. Nichols. 2000. Molecular epidemiological analysis of Cryptosporidium spp. in the United Kingdom: results of genotyping Cryptosporidium spp. in 1,705 fecal samples from humans and 105 fecal samples from livestock animals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3984-3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLauchlin, J., D. P. Casemore, S. Moran, and S. Patel. 1998. The epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis: application of experimental sub-typing and antibody detection systems to the investigation of water-borne outbreaks. Folia Parasitol. (Prague) 45:83-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLauchlin, J., S. Pedraza-Díaz, C. Amar-Hoetzeneder, and G. L. Nichols. 1999. Genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium strains from 218 patients with diarrhea diagnosed as having sporadic cryptosporidiosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3153-3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meinhardt, P. L., D. P. Casemore, and K. B. Miller. 1996. Epidemiologic aspects of human cryptosporidiosis and the role of waterborne transmission. Epidemiol. Rev. 18:118-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan-Ryan, U. M., A. Fall, L. A. Ward, N. Hijjawi, I. Sulaiman, R. Fayer, R. C. Thompson, M. Olson, A. Lal, and L. Xiao. 2002. Cryptosporidium hominis n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) from Homo sapiens. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 49:433-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgan, U. M., L. Xiao, B. D. Hill, P. O'Donoghue, J. Limor, A. A. Lal, and R. C. A. Thompson. 2000. Detection of the Cryptosporidium parvum “human” genotype in a dugong (Dugong dugong). J. Parasitol. 86:1352-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedraza-Díaz, S., C. Amar, G. L. Nichols, and J. McLauchlin. 2001. Nested polymerase chain reaction for amplification of the Cryptosporidium oocyst wall protein gene. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:49-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng, M. M., O. Matos, W. Gatei, P. Das, M. Stantic-Pavlinic, C. Bern, I. M. Sulaiman, S. Glaberman, A. A. Lal, and L. Xiao. 2001. A comparison of Cryptosporidium subgenotypes from several geographic regions. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2001(Suppl.):28S-31S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith, H. V., R. A. B. Nichols, M. Mallon, A. MacLeod, A. Tait, W. J. Reilly, L. M. Browning, D. Gray, S. W. J. Reid, and J. M. Wastling. 2005. Natural Cryptosporidium hominis infections in Scottish cattle. Vet. Rec. 156:710-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith, H. V., S. M. Cacciò, A. Tait, J. McLauchlin, and A. R. C. Thompson. 2006. Tools for investigating the environmental transmission of Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Trends Parasitol. 22:160-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith, H. V., R. A. B. Nichols, W. Weir, M. Mallon, A. Mcleod, J. M. Wastling, W. J. Reilly, and A. Tait. 2004. Molecular investigations into waterborne outbreaks, incidents and events involving Cryptosporidium contamination, p. 85-90. In S. Latham, H. V. Smith, and J. M. Wastling (ed.), Workshop on the application of genetic fingerprinting for the monitoring of Cryptosporidium in humans, animals and the environment. American Water Works Research Association, Drinking Water Inspectorate, and UK Water Industry Research Limited, Boulder, Colorado, 3 to 5 August 2003.

- 32.Spano, F., L. Putignani, A. Crisanti, P. Sallicandro, U. M. Morgan, S. M. Le Blancq, L. Tchack, S. Tzipori, and G. Widmer. 1998. Multilocus genotypic analysis of Cryptosporidium parvum isolates from different hosts and geographical origins. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3255-3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strong, W. B., J. Gut, and R. G. Nelson. 2000. Cloning and sequence analysis of a highly polymorphic Cryptosporidium parvum gene encoding a 60-kilodalton glycoprotein and characterization of its 15- and 45-kilodalton zoite surface antigen products. Infect. Immun. 68:4117-4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sulaiman, I. M., A. A Lal, and L. Xiao. 2001. A population genetic study of the Cryptosporidium parvum human genotype parasites. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2001(Suppl.):24S-27S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willocks, L., A. Crampin, L. Milne, C. Seng, M. Susman, R. Gair, M. Moulsdale, S. Shafi, R. Wall, R. Wiggins, N. Lightfoot, et al. 1998. A large outbreak of cryptosporidiosis associated with a public water supply from a deep chalk borehole. Commun. Dis. Public Health 1:239-243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao, L., R. Fayer, U. Ryan, and S. J. Upton. 2004. Cryptosporidium taxonomy: recent advances and implications for public health. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:72-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou, L., A. Singh, J. Jiang, and L. Xiao. 2003. Molecular surveillance of Cryptosporidium spp. in raw wastewater in Milwaukee: implications for understanding outbreak occurrence and transmission dynamics. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5254-5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.