Abstract

The analysis of the gyrA and gyrB genes of a panel of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis isolates from types I, II, and III detected type-specific single nucleotide polymorphisms. Based on these results, we developed a PCR and restriction enzyme analysis to discriminate type I and III isolates. The application of this technique would be the unique strategy to characterize these strains when there is not enough bacterial growth to perform pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and IS900 restriction fragment length polymorphism.

Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis is responsible for paratuberculosis (Johne's disease), a chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract that affects mainly livestock and wild ruminants. In addition, this microorganism is under study due to its possible implication as the etiological agent in Crohn's disease, affecting human beings (6, 21).

M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains have been classified into three major groups (sheep [type I], cattle [type II], and intermediate [type III]) based on their growth rates and molecular characterizations by IS900 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) (23) and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), respectively (10, 28). Rapid tools have been designed to distinguish type II from type I (7, 11); however, there is not a quick technique to further distinguish between types I and III. Therefore, when there is not enough bacterial growth to perform RFLP or PFGE, these isolates cannot be accurately classified, and they are named as type I/III (8).

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are changes in a single base at a specific position in the genome (16, 30). A correlation of SNP with phenotypic diversity has been established for some mycobacterial species, encouraging its use in order to distinguish among them at the level of bacterial strains (1, 4, 12, 18).

The genes gyrA and gyrB within the genus Mycobacterium have been analyzed in order to perform phylogenetic studies (2, 3, 14). The gyrB gene has been proposed to be a suitable phylogenetic marker, due to its average substitution rate at synonymous sites of 0.7% to 0.8% per 1 million years, much lower than that seen for some other phylogenetic markers, such as the 16S rRNA gene (14). In previous studies, analysis of polymorphisms in this gene has been used to differentiate between closely related strains (22).

Therefore, the aim of our study was the analysis of SNPs in the gyrA and gyrB genes to find a relationship with the subdivision of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains. The combination of SNPs found in each of the genes was able to divide types I, II, and III. Furthermore, we developed a PCR and restriction enzyme analysis (PCR-REA) to identify type I and III strains.

Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis isolates.

A panel of 20 M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis isolates was selected according to their difference in terms of strain type (type I [n = 5], type II [n = 7], type III [n = 5], and type I/III [n = 3]), geographic origin (Spain, Scotland, and Denmark), and host distribution (Table 1). These isolates were obtained from a pool of ileocecal valve and mesenteric lymph node samples as described in previous studies (13) and were subcultured onto selective growth media with mycobactin J (Dismalab, Madrid, Spain) (9).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial collection of the Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis isolates used in this study

| Isolate | PFGE typea | Herd/flock no. | Geographic originb | Host |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAM 38 | III | Herd 1 | Madrid | Goat |

| CAM 40 | III | Herd 1 | Madrid | Goat |

| CAM 42 | III | Herd 1 | Madrid | Goat |

| CAM 86 | III | Herd 2 | Madrid | Goat |

| CAM 87 | III | Herd 2 | Madrid | Goat |

| MI05/03132 | I/IIIc | Herd 3 | Castilla-La Mancha | Goat |

| 619 | I/IIIc | Herd 4 | Castilla-La Mancha | Cattle |

| 841 | I/IIIc | Herd 4 | Castilla-La Mancha | Cattle |

| CAM 19 | II | Herd 5 | Madrid | Goat |

| CAM 20 | II | Herd 6 | Madrid | Goat |

| 464 | II | Herd 7 | Madrid | Goat |

| CAM 63 | II | Herd 8 | Madrid | Goat |

| CAM 72 | II | Herd 9 | Madrid | Goat |

| 896 | II | Herd 10 | Castilla y León | Cattle |

| 940 | II | Herd 10 | Castilla y León | Cattle |

| 208G | I | Flock 1 | Shetland | Sheep |

| 213G | I | Flock 1 | Shetland | Sheep |

| 235G | I | Flock 1 | Shetland | Sheep |

| M189 | I | Flock 2 | Midlothian | Sheep |

| 21P | I | Flock 3 | Faroe Islands | Sheep |

Geographic origin details: Madrid (central Spain), Castilla-La Mancha (central-south Spain), Castilla y León (central-north Spain), Shetland (north Scotland), Midlothian (central-east Scotland), and the Faroe Islands (northwest Denmark).

PFGE could not be performed for these strains.

Colonies were recovered from the tubes and submitted to a PCR analysis for the presence of an IS900 fragment (15, 19). Moreover, IS1311 PCR-REA (17) for every isolate and PFGE were performed to confirm the strain type.

Analysis of sequences of the gyrA and gyrB genes.

Primers (Table 2) were designed using Primer 3software (http://biotools.umassmed.edu/bioapps/primer3_www.cgi) for both the gyrA gene (GenBank accession no. 2720426 [genome number NC_002944]; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank) and the gyrB gene (GenBank accession no. 2717659). PCR was carried out using a HotStart Taq DNA polymerase kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Each tube contained 5 μl of DNA sample, 1× buffer, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Biotools, B&M Labs, S.A., Madrid, Spain), 1× Q solution, 1 μl of each primer (8 μM), and 0.625 U of HotStart polymerase. PCR was undertaken with a MyCycler thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) under the following conditions: denaturation at 94°C for 15 min and 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 60°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min, with a final cycle of extension at 72°C for 5 min.

TABLE 2.

List of PCR primers used for gyrA and gyrB analysis

| Genea | Primer pair (5′-3′) | Length of amplified fragment | Location of primersb |

|---|---|---|---|

| gyrA-1 | (F) CCATGTACGACTCGGGTTTC | 746 bp | 176-195 |

| (R) GGATTGGTCCTCGATATTGG | 902-921 | ||

| gyrA-2 | (F) GGAGTCGTTGAGGTGGAAGA | 841 bp | 766-785 |

| (R) GGTACAGGTCGGTCTTGGTG | 1587-1606 | ||

| gyrA-3 | (F) ACGTCGTCGTCACCATCAC | 882 bp | 1547-1565 |

| (R) CCTCACCCAGATTCATCAGC | 2409-2428 | ||

| gyrB-1 | (F) AAGAAGGCGCAAGACGAATA | 1,001 bp | 16-35 |

| (R) AGCTTCTTGTCCTTGGCGTA | 997-1015 | ||

| gyrB-2 | (F) GTACGCCAAGGACAAGAAGC | 897 bp | 996-1016 |

| (R) GTGGGATCCATTGTGGTTTC | 1873-1892 |

The gyrA and gyrB genes were amplified into three and two fragments, respectively.

Location of forward (F) and reverse (R) primers as shown by nucleotide numbers for gyrA and gyrB genes of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis K-10.

Purification of the PCR product was undertaken with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN GmbH), and the product was sequenced using an ABI Prism 3730 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) (CIB Sequencing Facilities, Madrid, Spain). Chromatograms of forward and reverse sequences were then evaluated with Biological Sequence Alignment Editor software and compared with Mega 3.1 results to establish complete alignments for all the isolates. In addition, every sequence was submitted to nucleotide-nucleotide BLAST against M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis K-10 to identify the locations of SNPs.

The analysis of the sequences revealed a total of nine SNPs, four of them representing a change in coded amino acids (Table 3) . In the gyrA gene, the SNPs were located at positions 868, 1653, 1822, and 1986; two of them (at positions 868 and 1653) were implicated in nonsynonymous modifications, changing from hydrophilic amino acids into amino acids belonging to the basic group. The sequencing of the gyrB gene in the studied isolates showed five SNPs at positions 108, 264, 494, 1353, and 1626; a total of two represented a change in coded amino acids (at positions 264 and 494) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

SNPs found in gyrA and gyrB genes and encoded amino acids for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain K-10 and types I, II, III, and I/III

| Gene | Base position | SNP (encoded amino acid) for indicated strain or typea

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-10b | Type I | Type II | Type III | Type I/IIIc | ||

| gyrA | 868 | GAG (Glu) | AAG (Lys) | GAG (Glu) | GAG (Glu) | GAG (Glu) |

| 1653 | AAC (Asn) | AAA (Lys) | AAC (Asn) | AAA (Lys) | AAA (Lys) | |

| 1822 | CGG (Arg) | AGG (Arg) | CGG (Arg) | AGG (Arg) | AGG (Arg) | |

| 1986 | GGC (Gly) | GGC (Gly) | GGC (Gly) | GGT (Gly) | GGT (Gly) | |

| gyrB | 108d | TCT (Ser) | TCC (Ser) | TCT (Ser) | TCC (Ser) | TCC (Ser) |

| 264d | ATG (Met) | ATT (Ile) | ATG (Met) | ATT (Ile) | ATT (Ile) | |

| 494d | GCC (Ala) | GTC (Val) | GCC (Ala) | GTC (Val) | GTC (Val) | |

| 1353 | GAT (Asp) | GAC (Asp) | GAT (Asp) | GAC (Asp) | GAC (Asp) | |

| 1626 | ATC (Ile) | ATC (Ile) | ATC (Ile) | ATT (Ile) | ATT (Ile) | |

SNPs characteristic of type I and type III are in boldface.

M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain K-10 (gyrA, accession no. 2720426; gyrB, accession no. 2717659).

Strains in which PFGE or IS900-RFLP could not be performed.

SNPs for these base positions have been previously described for types I and II (18).

Differentiation of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis types.

The combination of SNPs found in this study within the gyrA and gyrB genes separately allow classification into types I, II, and III. In type I, the SNP found at nucleotide 868 of the gyrA gene resulted in an amino acid change (glutamate), while in types II, III, and I/III, a G was found upon sequencing. Type III and I/III isolates presented two specific SNPs. The first was located at position 1986 of the gyrA gene, with a T sequenced instead of the C found in types I and II; the second SNP was found at base 1626 of the gyrB gene, with a change in a T instead of the C found in types I and II. Type II isolates were distinguished by six specific SNPs, which were located at nucleotides 1653 and 1822 of the gyrA gene and at nucleotides 108, 264, 494, and 1353 of the gyrB gene.

M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type differentiation by PCR-REA.

A PCR-REA was designed to detect the polymorphism in the gyrB gene at position 1626, the SNP that allowed types I and II to be distinguished from type III. The 897-bp PCR products were submitted to restriction analysis with the enzyme Hpy188-III (New England Biolabs). Digestion was performed with 10 μl of PCR products, 5 U of enzyme, 1× NE buffer 4, and 0.5 μl of 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin. Afterwards, digestion products were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 2.5% agarose gel with a molecular size marker (100-bp ladder) (Biotools, B&M Labs S.A.) and stained with iQ SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad).

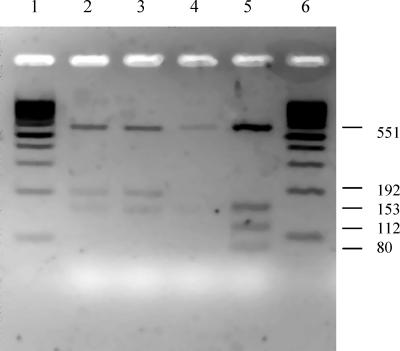

The restriction led to a four-band pattern (551, 153, 112, and 80 bp) for type I and type II isolates in which the codon ATC was present and to three bands (551, 192, and 153 bp) for isolates of type III (Fig. 1). The pattern obtained with type I/III isolates matched the pattern characteristic of type III isolates.

FIG. 1.

REA patterns obtained after Hpy188-III digestion of the PCR product of the gyrB-2 fragment (897 bp). Lanes: 1 and 6, 100-bp-ladder molecular size markers; 2 and 3, digested PCR products from type III strains; 4 and 5, digested PCR products from type I and II strains, respectively.

The development of molecular techniques to identify M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains that are characterized by extremely low growth rates and are refractory to culture (types I and III) would be useful for diagnostic laboratories. We have based our study on the presence of SNPs, a relatively new molecular strategy with the advantages of being inexpensive and having a high-throughput production (29). For instance, SNP analysis has been used recently with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis isolates to differentiate cattle (type II) and sheep (type I/III) isolates (18, 25).

The most useful finding from the sequencing of the gyrB gene was the SNP found at nucleotide 1626, which was able to distinguish type III from the other types and was susceptible to PCR-REA. This finding is a valuable tool to accurately identify these isolates without the need to perform time-consuming protocols. Until this time, the differentiation between types I and III was possible only by using PFGE and IS900 RFLP, which require substantial amounts of DNA (10, 28); this is often a limitation due to the fastidious growth requirements and long incubation periods characteristic of these strains. The combination of SNPs of the isolates previously named as type I/III matched the pattern found in type III isolates. This result is epidemiologically consistent with our previous finding that no type I isolates have been found in the Spanish geographic area from which these isolates were collected (8, 10). However, type I has been reported to be present in other areas (26).

There was also a combination of polymorphisms that characterized type II isolates; three of them had already been described (18). However, these are of less practical usefulness, because the identification of type II (cattle) can be performed by the PCR described by Collins et al. (7), by the IS1311 PCR-REA (17), or by type I-specific locus PCRs performed following the protocol of Dohmann et al. (11).

These results would suggest that the SNPs are type specific. The gyrA and gyrB sequences of the type II isolates were identical of those from M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain K-10. Also, both gyrA and gyrB sequences were identical among all isolates within a type group, despite their different geographic areas or host origins. Two of the five substitutions found in the gyrB gene were nonsynonymous, while the substitutions present in the members of the M. tuberculosis complex were synonymous (14, 22). The origin of the changes found at the M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis types may be caused by the divergent evolution or may have been developed by selective pressure from antibiotic treatment.

PCR-REA assays would be of great advantage in testing M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis DNA directly extracted from tissues, blood, milk, or other samples of human or veterinary origin that are culture negative and isolates that are not easily subcultured (5, 24, 27). These assays will help to improve the knowledge and characterization of the role of these pathogens during the infection, due to the possible relationship between M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis type and pathogenesis (9, 20). Nowadays, despite the worldwide prevalence of the infection, there is limited information on M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis isolates due to the absence of quick molecular tools. This may be the reason why, at the present time, type III isolates have been reported only in Spain (10). We think this technique complements the already existing fast molecular techniques, but more studies pertaining to different geographic areas would be convenient to assess the usefulness of this technique as a routine test for identification purposes.

In addition, the gyrA and gyrB genes, in combination with other selected target genes, could be used as phylogenetic markers to gain an insight into the taxonomy and evolution of the subspecies, as has been achieved for the M. tuberculosis complex. These results are preliminary due to the limited sample size and the restricted geographic origin of the isolates. A widespread and definitive epidemiological study should be undertaken to validate these results and to test the usefulness of this technique.

In summary, the polymorphisms found in the gyrA and gyrB genes are specific for types I, II, and III of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. The SNP present in the gyrB gene was susceptible to PCR-REA, and to our knowledge, this is the first description of a fast molecular tool able to divide M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains into these three major groups.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession number for the gyrA partial sequence from type I is EU029115, and that for the partial sequence from type III is EU029113. The accession number for the gyrB partial sequence from type I is EU029112, and that for the partial sequence from type III is EU129114.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by project AGL2005-07792 of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology, EU Project ParaTBTools FP6-2004-FOOD-3B-023106, and by the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. E.C. is the recipient of a grant (AP2005-0696 GAN) from the Ministry of Education and Culture.

We thank the staff of SADNA (C.I.B. Madrid) for sequencing. We appreciate the technical help of F. Lozano and N. Moya. We are grateful to D. Morey for careful revision of the manuscript. We thank L. Carbajo, J. L. Paramio, and J. L. Sáez-Llorente for their continuous encouragement.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 August 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alland, D., T. S. Whittam, M. B. Murray, M. D. Cave, M. H. Hazbon, K. Dix, M. Kokoris, A. Duesterhoeft, J. A. Eisen, C. M. Fraser, and R. D. Fleischmann. 2003. Modeling bacterial evolution with comparative- genome-based marker systems: application to Mycobacterium tuberculosis evolution and pathogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 185:3392-3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aranaz, A., D. Cousins, A. Mateos, and L. Dominguez. 2003. Elevation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis subsp. caprae Aranaz et al. 1999 to species rank as Mycobacterium caprae comb. nov., sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1785-1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker, L., T. Brown, M. C. Maiden, and F. Drobniewski. 2004. Silent nucleotide polymorphisms and a phylogeny for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1568-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brosch, R., S. V. Gordon, M. Marmiesse, P. Brodin, C. Buchrieser, K. Eiglmeier, T. Garnier, C. Gutierrez, G. Hewinson, K. Kremer, L. M. Parsons, A. S. Pym, S. Samper, S. D. Van, and S. T. Cole. 2002. A new evolutionary scenario for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3684-3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buergelt, C. D., and J. E. Williams. 2004. Nested PCR on blood and milk for the detection of Mycobacterium avium subsp paratuberculosis DNA in clinical and subclinical bovine paratuberculosis. Aust. Vet. J. 82:497-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bull, T. J., E. J. McMinn, K. Sidi-Boumedine, A. Skull, D. Durkin, P. Neild, G. Rhodes, R. Pickup, and J. Hermon-Taylor. 2003. Detection and verification of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in fresh ileocolonic mucosal biopsy specimens from individuals with and without Crohn's disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2915-2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins, D. M., M. De Zoete, and S. M. Cavaignac. 2002. Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains from cattle and sheep can be distinguished by a PCR test based on a novel DNA sequence difference. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4760-4762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Juan, L., J. Alvarez, A. Aranaz, A. Rodriguez, B. Romero, J. Bezos, A. Mateos, and L. Dominguez. 2006. Molecular epidemiology of types I/III strains of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis isolated from goats and cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 115:102-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Juan, L., J. Alvarez, B. Romero, J. Bezos, E. Castellanos, A. Aranaz, A. Mateos, and L. Dominguez. 2006. Comparison of four different culture media for isolation and growth of type II and type I/III Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains isolated from cattle and goats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5927-5932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Juan, L., A. Mateos, L. Dominguez, J. M. Sharp, and K. Stevenson. 2005. Genetic diversity of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis isolates from goats detected by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Vet. Microbiol. 106:249-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dohmann, K., B. Strommenger, K. Stevenson, L. de Juan, J. Stratmann, V. Kapur, T. J. Bull, and G. F. Gerlach. 2003. Characterization of genetic differences between Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis type I and type II isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5215-5223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filliol, I., A. S. Motiwala, M. Cavatore, W. Qi, M. H. Hazbon, M. Bobadilla del Valle, J. Fyfe, L. Garcia-Garcia, N. Rastogi, C. Sola, T. Zozio, M. I. Guerrero, C. I. Leon, J. Crabtree, S. Angiuoli, K. D. Eisenach, R. Durmaz, M. L. Joloba, A. Rendon, J. Sifuentes-Osornio, A. Ponce de León, M. D. Cave, R. Fleischmann, T. S. Whittam, and D. Alland. 2006. Global phylogeny of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis: insights into tuberculosis evolution, phylogenetic accuracy of other DNA fingerprinting systems, and recommendations for a minimal standard SNP set. J. Bacteriol. 188:759-772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greig, A., K. Stevenson, V. Perez, A. A. Pirie, J. M. Grant, and J. M. Sharp. 1997. Paratuberculosis in wild rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Vet. Rec. 140:141-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasai, H., T. Ezaki, and S. Harayama. 2000. Differentiation of phylogenetically related slowly growing mycobacteria by their gyrB sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:301-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunze, Z. M., F. Portaels, and J. J. McFadden. 1992. Biologically distinct subtypes of Mycobacterium avium differ in possession of insertion sequence IS901. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2366-2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maiden, M. C., J. A. Bygraves, E. Feil, G. Morelli, J. E. Russell, R. Urwin, Q. Zhang, J. Zhou, K. Zurth, D. A. Caugant, I. M. Feavers, M. Achtman, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3140-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsh, I., R. Whittington, and D. Cousins. 1999. PCR-restriction endonuclease analysis for identification and strain typing of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium subsp. avium based on polymorphisms in IS1311. Mol. Cell. Probes 13:115-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marsh, I. B., and R. J. Whittington. 2007. Genomic diversity in Mycobacterium avium: single nucleotide polymorphisms between the S and C strains of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and with M. a. avium. Mol. Cell. Probes 21:66-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Millar, D. S., S. J. Withey, M. L. Tizard, J. G. Ford, and J. Hermon-Taylor. 1995. Solid-phase hybridization capture of low-abundance target DNA sequences: application to the polymerase chain reaction detection of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium subsp. silvaticum. Anal. Biochem. 226:325-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motiwala, A. S., H. K. Janagama, M. L. Paustian, X. Zhu, J. P. Bannantine, V. Kapur, and S. Sreevatsan. 2006. Comparative transcriptional analysis of human macrophages exposed to animal and human isolates of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis with diverse genotypes. Infect. Immun. 74:6046-6056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naser, S. A., G. Ghobrial, C. Romero, and J. F. Valentine. 2004. Culture of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis from the blood of patients with Crohn's disease. Lancet 364:1039-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niemann, S., D. Harmsen, S. Rusch-Gerdes, and E. Richter. 2000. Differentiation of clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates by gyrB DNA sequence polymorphism analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3231-3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavlik, I., A. Horvathova, L. Dvorska, J. Bartl, P. Svastova, R. du Maine, and I. Rychlik. 1999. Standardisation of restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis for Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis. J. Microbiol. Methods 38:155-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sechi, L. A., A. M. Scanu, P. Molicotti, S. Cannas, M. Mura, G. Dettori, G. Fadda, and S. Zanetti. 2005. Detection and isolation of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis from intestinal mucosal biopsies of patients with and without Crohn's disease in Sardinia. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100:1529-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Semret, M., C. Y. Turenne, and M. A. Behr. 2006. Insertion sequence IS900 revisited. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1081-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sevilla, I., J. M. Garrido, M. Geijo, and R. A. Juste. 2007. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profile homogeneity of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis isolates from cattle and heterogeneity of those from sheep and goats. BMC Microbiol. 7:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sivakumar, P., B. N. Tripathi, and N. Singh. 2005. Detection of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in intestinal and lymph node tissues of water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) by PCR and bacterial culture. Vet. Microbiol. 108:263-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevenson, K., V. M. Hughes, L. de Juan, N. F. Inglis, F. Wright, and J. M. Sharp. 2002. Molecular characterization of pigmented and nonpigmented isolates of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1798-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ulgen, A., and W. Li. 2005. Comparing single-nucleotide polymorphism marker-based and microsatellite marker-based linkage analyses. BMC Genet. 6(Suppl. 1):S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urwin, R., and M. C. Maiden. 2003. Multi-locus sequence typing: a tool for global epidemiology. Trends Microbiol. 11:479-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]