Abstract

RNase footprinting and nitrocellulose filter binding assays were previously used to map one major and two minor binding sites for the cell protein eEF1A on the 3′(+) stem-loop (SL) RNA of West Nile virus (WNV) (3). Base substitutions in the major eEF1A binding site or adjacent areas of the 3′(+) SL were engineered into a WNV infectious clone. Mutations that decreased, as well as ones that increased, eEF1A binding in in vitro assays had a negative effect on viral growth. None of these mutations affected the efficiency of translation of the viral polyprotein from the genomic RNA, but all of the mutations that decreased in vitro eEF1A binding to the 3′ SL RNA also decreased viral minus-strand RNA synthesis in transfected cells. Also, a mutation that increased the efficiency of eEF1A binding to the 3′ SL RNA increased minus-strand RNA synthesis in transfected cells, which resulted in decreased synthesis of genomic RNA. These results strongly suggest that the interaction between eEF1A and the WNV 3′ SL facilitates viral minus-strand synthesis. eEF1A colocalized with viral replication complexes (RC) in infected cells and antibody to eEF1A coimmunoprecipitated viral RC proteins, suggesting that eEF1A facilitates an interaction between the 3′ end of the genome and the RC. eEF1A bound with similar efficiencies to the 3′-terminal SL RNAs of four divergent flaviviruses, including a tick-borne flavivirus, and colocalized with dengue virus RC in infected cells. These results suggest that eEF1A plays a similar role in RNA replication for all flaviviruses.

The eukaryotic translation elongation factor eEF1A constitutes 1 to 4% of the total soluble protein in actively dividing cells and is second only to actin in abundance (8, 12). eEF1A delivers aminoacylated tRNAs and GTP to the A site on the ribosome during protein synthesis. The eEF1A:GTP:aminoacylated tRNA complex then moves to the P site. eEF1A hydrolyzes GTP to GDP, which results in the release of eEF1A:GDP from the ribosome. In addition to its role in peptide chain elongation, eEF1A has been reported to bind to mRNA (30, 37), to bind to and bundle actin filaments (16, 29, 30), to sever microtubules (52), and to mediate protein degradation via ubiquitin-dependent pathways (19, 20).

West Nile virus (WNV) is a member of the genus Flavivirus in the family Flaviviridae. WNV is transmitted by arthropods and is maintained in a mosquito-bird transmission cycle in nature with humans as incidental hosts. WNV infection in humans is usually asymptomatic or causes a mild febrile illness. Fewer than 1% of all infections result in a severe central nervous system disease that can sometimes be fatal (41, 56). The WNV genome is a positive-polarity, single-stranded RNA of about 11 kb in length. Translation and replication of the viral genome occur in the cytoplasms of infected cells. The genome contains a single open reading frame (ORF) encoding a polyprotein of approximately 3,000 amino acids that is cleaved by host and viral proteases into three structural and seven nonstructural proteins. The genome is flanked by 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTR). The WNV 5′ UTR is 96 nucleotides (nt) long, while the 3′ UTR is 632 nt long. The genomic 3′-terminal nucleotides form a stem-loop (SL) that is predicted to be highly conserved among all flaviviruses (6, 22, 34, 58). This 3′-terminal region is thought to function as a promoter for viral minus-strand synthesis; deletion of the 3′ SL in a flavivirus infectious clone was lethal, providing evidence that cis-acting elements were present in this region (5). Previously, three cellular proteins with molecular masses of 105, 84, and 52 kDa were reported to bind specifically to the WNV 3′-terminal (+) SL RNA (2). The 52-kDa protein was subsequently identified as eEF1A (3). The dissociation constant for the interaction between eEF1A and the WNV 3′(+) SL RNA is 10−9 M, which is similar to that of the interaction between eEF1A and individual charged tRNAs (43). One major and two minor eEF1A binding sites were previously mapped on the WNV 3′(+) SL RNA by use of RNase footprinting and nitrocellulose filter binding assays (3).

eEF1A has also been reported to bind to the genomic 3′-terminal tRNA-like structure (TLS) of the positive-strand RNA plant virus turnip yellow mosaic virus and to act as both a translational enhancer and a repressor of minus-strand synthesis (35, 36). eEF1A has been reported to bind to both the 3′ TLS and the viral polymerase of the positive-strand RNA plant virus tobacco mosaic virus (60). The bacterial homolog of eEF1A was shown to be a functional part of the viral replicase holoenzyme of the positive-strand RNA bacteriophage Qβ (4, 7, 39, 47, 48). Similarly, for the negative-strand RNA virus vesicular stomatitis virus, eEF1A was reported to be a component of the viral transcriptase complex and was required for replicase activity in vitro (42). eEF1A was also reported to interact with the bovine viral diarrhea virus nonstructural protein NS5A, the hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein NS4A, and the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag polyprotein (10, 24, 26).

Various mutations were introduced into the previously mapped major binding site of the WNV 3′ SL RNA in a WNV infectious clone, and the effect of these mutations on virus production, viral RNA translation, and viral RNA synthesis was assessed. All of the mutations that altered eEF1A binding in vitro had a negative effect on virus production in cell culture. None of the mutations had an effect on the translation of viral proteins. Mutations that decreased the binding efficiency of eEF1A to the viral 3′(+) SL in vitro had a negative effect on viral minus-strand RNA synthesis, while mutations that increased the binding efficiency of eEF1A to the viral 3′(+) SL in vitro increased minus-strand RNA synthesis. The results strongly suggest that eEF1A plays a role in the initiation of flavivirus minus-strand synthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

Baby hamster kidney 21/WI2 cells (hereafter referred to as BHK cells) were grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Eagle's minimum essential medium (MEM) containing 4.5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 10 μg/ml gentamicin (54). C6/36 cells were grown at 27°C in Eagle's MEM containing 10% FBS, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, and 10 μg/ml of gentamicin. A pool of WNV strain Eg101 (2 × 108 PFU/ml) was prepared in BHK cells as described previously (46). Dengue virus 2 (Den 2), strain Bangkok D80-100, was provided by Walter Brandt (Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Washington, DC). A 10% (wt/vol) suckling mouse brain homogenate pool with a titer of 2 × 106 PFU/ml was prepared.

Preparation of S100 cell extracts.

Cells were grown to confluence in T150 tissue culture flasks, washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), harvested by scraping, and pelleted by centrifugation at 150 × g. The cells were resuspended in hypotonic cell lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 20% glycerol, 10 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin), vortexed for 30 s, kept on ice for 10 min, and then lysed by the addition of 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 2,000 × g. The resulting supernatant was adjusted to 14 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 6 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM NaCl, 60 mM KCl, and 50% glycerol, clarified by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 15 min, and stored at −20°C. The total protein concentration of the S100 supernatant was approximately 1 μg/μl.

Purification of eEF1A.

eEF1A was purified from BHK cell extracts by ammonium sulfate precipitation and fractionated on a Mono S HR5/5 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) as previously described (3). eEF1A cDNA amplified by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) from mRNA purified from BHK cells was cloned into the T7 expression vector pCR T7/CT-TOPO according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (B. Smith, J. L. Blackwell, and M. A. Brinton, unpublished data). Primers used are shown in Table 1. The cDNA clone of eEF1A was confirmed by sequencing. Recombinant eEF1A was expressed in Origami cells (Novagen, Madison, WI). Protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), and cells were harvested after 4 h. The cell pellet was resuspended in extraction buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.6) and lysed with a French pressure cell (SIM-AMINCO Spectronic Instrument Inc., Rochester, NY). The cell lysate was centrifuged at 3,000 × g to pellet cell debris. Recombinant protein was bound to Talon metal affinity resin (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) that was then applied to a 2-ml Talon disposable gravity column (Clontech). The column was washed with wash buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 7.6). Recombinant protein was eluted with elution buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, pH 7.6), dialyzed against 2 liters of dialysis buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.6) in a Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassette (Pierce, Rockford, IL) to remove imidazole, and concentrated to 200 to 400 ng/μl using a Centricon 10 concentrator (Amicon, Beverly, MA).

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primers

| Primera | Sequenceb |

|---|---|

| Mut A for | 5′-GACTAGGAGATCTTCTGCTCTGCACUATCAGCCACACGGC-3′ |

| Mut A rev | 5′-AGGTGCGGCGACGATAGTCATGCCCCGC-3′ |

| Mut B for | 5′-GACTAGGAGATCTTCTGCTCTGTGGAATCAGCCACACGGC-3′ |

| Mut B rev | 5′-AGGTGCGGCGACGATAGTCATGCCCCGC-3′ |

| Mut C for | 5′-GACTAGGAGATCTTCTGCTCTGTGGAATCAGCCACACGGC-3′ |

| Mut C rev | 5′-CGACTCTAGAGATCCTGTGTTCTCGTGGCACCAGCCACC-3′ |

| Mut D for | 5′-GACTAGGAGATCTTCTGCTCTGTGTGATCAGCCACACGGC-3′ |

| Mut D rev | 5′-AGGTGCGGCGACGATAGTCATGCCCCGC-3′ |

| E. Rev. for | 5′-GACTAGGAGATCTTCTGCTCTGCGTGATCAGCCACACGGC-3′ |

| E. Rev. rev | 5′-AGGTGCGGCGACGATAGTCATGCCCCGC-3′ |

| Mut E for | 5′-TAGTGGAGACCCCGTGCCAAC-3′ |

| Mut E rev | 5′-CGACTCTAGAGATCCTGTGTTCTCTGGGCACCAGCCACC-3′ |

| Mut F for | 5′-TAGTGGAGACCCCGTGCCAAC-3′ |

| Mut F rev | 5′-CGACTCTAGAGATCCTGTGTTCTCGTGGCACCAGCCACC-3′ |

| Mut G for | 5′-GACTAGGAGATCTTCTGCTCTGCACAATCAGCCACACGG-3′ |

| Mut G rev | 5′-AGGTGCGGCGACGATAGTCATGCCCCGC-3′ |

| eEF1A for | 5′-ATGGGAAAGGAAAAGACTCAC-3′ |

| eEF1A rev | 5′-TTTAGCCTTCTGAGCTTTCTGGG-3′ |

| pYFV(+)3′SL for | 5′-TACGGAATTCTATTGACGCCAGGGAAAG-3′ |

| pYFV(+)3′SL rev | 5′-TACGAAGCTTAGTGGTTTTGTGTTTGTC-3′ |

| pTBEV(+)3′SL for | 5′-TACGGAATTCAATTCCCCCTCGGTAGAG-3′ |

| pTBEV(+)3′SL rev | 5′-TACGAAGCTTAGCGGGTGTTTTTCCGAG-3′ |

| WNV T7 for | 5′-[T7]CCTGGGATAGACTAGGAGATCTTCTGCTC-3′ |

| WNV T7 rev | 5′-AGGTGCGGCGACGATAGTCATGCCCCGC-3′ |

| Den 2 T7 for | 5′-[T7]CTGGGAGAGACCAGAGATCCTGCTGTCTC-3′ |

| Den 2 T7 rev | 5′-AGAACCTGTTGATTCAAC-3′ |

| TBEV T7 for | 5′-[T7]CCCCCTCAACAGAGGGGGGGCGGTTC-3′ |

| TBEV T7 rev | 5′-AGCGGGTGTTTTTCCGAG-3′ |

| YFV T7 for | 5′-[T7]CCAGGGAAAGACCGGAGTGGTTCTCTGC-3′ |

| YFV T7 rev | 5′-AGTGGTTTTGTGTTTGTC-3′ |

Mut, mutant; rev, reverse; for, forward; E. Rev., engineered revertant; T7, T7 promoter sequence.

Underlining indicates introduced mutations.

DNA templates for RNA transcription.

The WNV 3′(+) SL template, pWNV(+)3′ SL, contained the 3′-terminal 111 nt of the WNV Eg101 genome RNA cloned into pCR1000 (Invitrogen), and its construction has been described previously (2). The construction of the pDen2(+)3′SL plasmid, which contained the terminal 107 nt of Den 2 strain 16681 genomic RNA subcloned into the pCR1000 vector, was described previously (50). pYFV(+)3′SL was subcloned from pYF5′3′IV (a gift from Charles Rice, Rockefeller University, NY) into pGEM3Zf(−). pTBEV(+)3′SL was subcloned from p3HA (a gift from Christian Mandl, Institute of Virology, Vienna, Austria), which contains the 3′ terminus of the tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) (Hypr strain) genome cloned into pGEM3Zf(−) (55). The sequence of each of these clones was confirmed by sequencing. The plasmids described above were used to generate PCR templates that contained a T7 promoter for RNA transcription as described previously (2). Primers used are shown in Table 1. PCR products were purified using a QIAGEN PCR clean-up kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA).

RNA transcripts.

The PCR products described above were used as templates for transcription of WNV, yellow fever virus (YFV), TBEV, and Den 2 3′(+) SL RNAs in the presence of [α-32P]GTP by use of T7 RNA polymerase (50 U) according to the manufacturer's protocol (Ambion, Austin, TX) for 1 h at 37°C. Transcription reactions were stopped by the addition of DNase (1 U) for 15 min at 37°C, and the RNA was gel purified and precipitated with ethanol as described previously (14). The purified RNAs were resuspended in 100 μl of RNase-free storage buffer (100 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.2] 300 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 25% glycerol) or water. Radioactivity was measured using a scintillation counter (Beckman LS6500), and the specific activity (∼1.3 × 107 cpm/μg) was calculated as described previously (3).

Gel mobility shift assays.

Purified recombinant eEF1A and S100 cytoplasmic extracts were incubated in gel shift buffer (GS buffer) with a 32P-labeled 3′ viral RNA probe (2,000 cpm or approximately 0.2 nM final concentration per reaction), poly(I-C) (50 ng), and RNase inhibitor (Ambion) (10 units) for 30 min at room temperature. The RNA-protein complexes (RPCs) were resolved by nondenaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in 1× TBE buffer. The percent RNA bound was quantified with a Fuji BAS 1800 analyzer (Fuji Photo Film Co., Japan) and Image Gauge software (Science Lab, 98, version 3.12, Fuji Photo Film Co.). Analysis of UV-induced cross-linked RPCs was performed as described previously (3).

Mutagenesis of a WNV infectious clone.

The construction and characteristics of the chimeric full-length WNV infectious clone were previously described (61). An extra A was inserted at nucleotide position 11019. This addition did not affect viral growth but stabilized the plasmid in Escherichia coli. Infectious clone DNA was amplified in TOP10 cells (Invitrogen) and purified using a plasmid miniprep kit (QIAGEN). The strategy used to introduce mutations in the 3′ SL was described previously (17). Primer sequences used to generate the mutant viral cDNAs are shown in Table 1. The replication-deficient mutant, which had the conserved polymerase motif GDD mutated to a GAA, was made by subcloning the mutated fragment, which was generated by digestion of a replication-deficient Eg101 replicon with XbaI and BstI, into the infectious clone (G. Radu, S. V. Scherbik, and M. A. Brinton, unpublished data). All mutations made to the infectious clone DNA were confirmed by sequencing.

In vitro transcription of WNV genomic RNA.

Parental or mutant infectious clone plasmid DNA was linearized at the 3′ end of the WNV cDNA with the restriction enzyme XbaI and then purified using a PCR cleanup kit (QIAGEN). The in vitro transcription of capped RNA was performed using the Message Maker SP6 transcription kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNase-free DNase was then added, and the reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. DNase was heat inactivated at 65°C for 15 min, and the reaction mixture was used directly for transfection of BHK cells.

Transfection of WNV genomic RNA into BHK cells.

RNA transfection was performed as described previously (17). Briefly, 0.1 or 1 μg of in vitro-transcribed viral genomic RNA was transfected into BHK cells (80 to 90% confluence) in six-well dishes with DMRIE-C according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). After a 2-h incubation at 37°C, the transfection medium was removed and the cells were overlaid with either 2 ml of 5% FCS-MEM or a 1:1 mixture of 1% agarose and 2× MEM containing 5% FBS. At 72 h after transfection, the agarose was removed and plaques were visualized using a methyl violet stain (10% ethanol, 0.5% methyl violet). Alternatively, when plaques were to be picked, the initial overlay was not removed and a second overlay of 0.05% neutral red solution, 0.5% agarose in 1× MEM was added, and plaques were visualized 8 h later. Virus in medium harvested from duplicate wells was titrated by plaque assay on BHK cells.

Viral growth curves.

Growth curves were performed as described previously (17). Briefly, duplicate confluent BHK or C6/36 monolayers in T25 flasks were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1. Aliquots of culture fluid were taken at 0, 10, 22, 29, and 48 h after infection of BHK cells and at 0, 10, 22, 29, 48, and 72 h after infection of C6/36 cells and stored at −80°C until titrated by plaque assay.

Analysis of virus revertant.

Revertant virus was first plaque purified, and then viral RNA was extracted and purified using TRI reagent LS (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A cDNA copy of the desired region of the revertant virus was amplified by RT-PCR and cloned into pTOPO-TA 2.1 (Invitrogen). Ten clones for each revertant virus were checked by DNA sequencing.

Analysis of intracellular viral RNA by real-time RT-PCR.

Full-length genomic RNAs were generated as described above. Replicate BHK monolayers in six-well tissue culture plates (80 to 90% confluence) were washed once with 2 ml of Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) and then transfected with 200 ng of RNA in DMRIE-C (Invitrogen). At the indicated times after transfection, each well was washed three times with 5 ml of growth medium, and total RNA within the cell was extracted using TRI reagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc.). The relative amount of intracellular viral genomic RNA was determined by real-time RT-PCR on an Applied Biosystems 7500 real-time PCR system using 200 ng of total RNA and the TaqMan one-step RT-PCR kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Applied Biosystems). The NS1 region primers used were 5′-GGCGGTTCTAGGAGAAGTCA-3′and 5′-CTCCTGTTGTGGTTGCTTCT-3′, and the Förster Resonance Energy Transfer probe was 5′-6-carboxyfluorescein-TGCACCTGGCCAGAAACCCACACTCTGT3′-6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine.

For the specific detection of viral minus-strand RNA, T7-tagged primer real-time RT-PCR was performed as previously described (27, 45). Briefly, 2 pmol of the minus-strand primer, 5′-GCGTAATACGACTCACTATAgagggcggttctaggagaagt-3′ (T7 tag sequence in uppercase boldface, NS1 sequence in lowercase), was incubated with 800 ng of total RNA in a TaqMan one-step RT-PCR mixture at 50°C for 30 min and then at 95°C for 30 min to inactivate the reverse transcriptase. Then, 20 pmol of 5′-GCGTAATACGACTCACTATA-3′ and of 5′-ctcctgttgtggttgcttc-3′ was added along with 5 pmol of the probe 5′-6-carboxyfluorescein-TGCACCTGGCCAGAAACCCACACTCTGT3′-6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine, and the PCR was performed as follows: 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and then 60°C for 1 min.

Analysis of all real-time RT-PCR data was done using the relative quantification software from Applied Biosystems and the cellular mRNA glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Applied Biosystems) as the endogenous control. The genomic RNA levels at 48 and 72 h after transfection were each expressed as the amount (n = fold) of change compared to the level of viral RNA present at 6 h after transfection. Levels of minus-strand RNA at 12, 24, and 48 h after transfection were each expressed as the amount (n = fold) of change compared to the level of viral RNA levels present at 2 h after transfection.

To assess the level of specificity of the minus-strand assay described above, in vitro-transcribed plus- and minus-strand RNAs were used to generate absolute standard curves with the same primers and protocol used for viral minus-strand detection in transfected cells. Analysis of the real-time RT-PCR data was done using the absolute quantification standard curve software from Applied Biosystems.

Confocal microscopy.

BHK cells grown to 60% confluence on 15-mm glass coverslips in wells of a 24-well plate were either transfected with 1 μg of viral RNA as described above or infected with WNV or Den 2 at an MOI of 0.1. The cells were fixed by incubation with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature and then permeabilized at the indicated times with methanol at −20°C for 10 min. Coverslips were washed with PBS and then blocked overnight with 5% horse serum (Invitrogen) in PBS. Primary antibodies used were mouse hyperimmune ascitic fluid (MHIAF) against WNV (a gift from Robert Tesh, UTMB, Galveston, TX) at a 1:100 dilution, rabbit anti-WNV NS3/NS5 made to gel-purified viral proteins as described previously (21) at a 1:50 dilution, a mouse anti-double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) antibody (English & Scientific Consulting, Szirak, Hungary) at a 1:200 dilution, and a goat anti-eEF1A antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at a 1:200 dilution in the NS3/NS5 colocalization experiments or a 1:700 dilution in the dsRNA colocalization experiments. Coverslips were incubated with primary antibody in PBS with 5% horse serum for 1 h at 37°C and then washed four times with PBS. Coverslips were next incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (chicken anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G [IgG]-Texas Red, chicken anti-mouse IgG-TR, or donkey anti-goat IgG fluorescein isothiocyanate [Santa Cruz Biotechnology]) in PBS with 5% horse serum at a 1:300 dilution and Hoechst dye to stain the nuclei. After being washed with PBS, the coverslips were mounted on glass slides with Prolong mounting medium (Invitrogen) and visualized with a 100× oil immersion objective on an LSM 510 laser confocal microscope by use of LSM 5 (version 3.2) software (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY). Relative fluorescence intensity was measured in 7-μm-diameter circles in three locations in the cytoplasms of 10 representative transfected BHK cells for each viral RNA by use of LSM 5 (version 3.2) software. Images compared for each experimental series were collected using the same instrument settings.

Mutagenesis of a NY99 WNV replicon.

The construction and characterization of the WNV luciferase-reporting replicon RlucRep was reported previously (31). A mutant RlucRep containing a 4-nt 5′-UGUG-3′ substitution in the major binding site for eEF1A was constructed by swapping the parental 3′ cDNA fragment located between the unique MluI (nt 10,436) and XbaI (3′ terminus of the genomic cDNA) restriction sites with the PCR fragment containing the substitution. The PCR fragment containing the 4-nt change was prepared via standard overlapping PCR. The cDNA clone of mutant RlucRep was verified by DNA sequencing. Conditions used for in vitro transcription, the transfection of replicon RNA, and the luciferase reporter assays were as previously described (51).

Coimmunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

Confluent monolayers of BHK cells in six-well tissue culture plates were mock infected or infected with WNV (MOI of 5) for 24 h. Cells were washed twice with 2 ml of PBS, scraped, pelleted at 700 × g, and resuspended in cell lysis buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.2], 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 1% NP-40, and complete mini-protease inhibitor [Roche]) at a concentration of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml. Cells were incubated on ice for 30 min and then sonicated four times for 5 s each by use of a Branson 450 sonifier (Danbury, CT). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 5 min (S2 lysate). The total protein concentration was approximately 200 ng/μl. Infected and mock-infected S2 lysates (200 μl) were precleared by incubation with protein A/G magnetic beads (New England Biolabs) at 4°C for 1 h. The beads were then removed by applying a magnetic field, and the cleared supernatant was used for subsequent experiments. Cleared supernatant was incubated for 1 h at 4°C with 2 μg of antibody against one of the following cellular proteins: eEF1A (Santa Cruz), HSP105 (Santa Cruz), or NFAR-1 or NFAR-2 (a gift from Sven-Erik Behrens, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA). Fresh protein A/G magnetic beads (25 μl) were then added, and after incubation at 4°C for 1 h, beads were recovered and washed seven times with 1 ml of cell lysis buffer, resuspended in 50 μl of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl, 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 2% mercaptoethanol, 0.5% bromophenol blue), and incubated at 70°C for 5 min. Beads were removed with a magnetic field, and the sample was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins were then electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked at 4°C overnight with Tris-buffered saline (50 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl) containing 5% milk and 0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated with a rabbit polyclonal anti-NS3/NS5 antibody or with anti-WNV MHIAF for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were then washed with Tris-buffered saline and incubated with a secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse [Santa Cruz]) for 1 h at room temperature. The washed blots were processed for enhanced chemiluminescence using a Super-Signal West Pico detection kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions and exposed to film.

Prediction of RNA secondary structures.

The predicted secondary structures of the terminal SL RNAs shown were determined with the Mfold program (version 3) (64).

RESULTS

Effect of mutation of the major eEF1A binding site in a WNV infectious clone on progeny virus production.

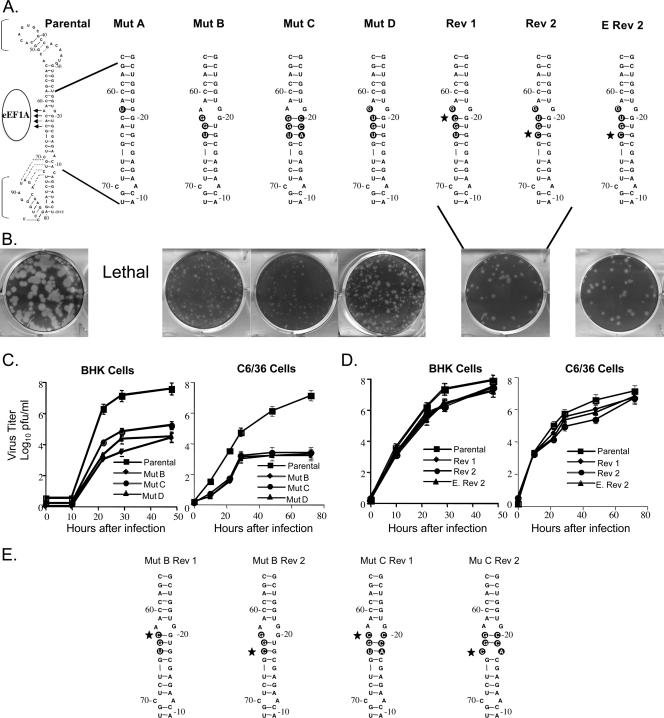

One major and two minor binding sites for eEF1A on the 3′(+) SL RNA of WNV were previously reported (3). The major eEF1A binding site (3′-ACAC-5′, nt 62 to 65 from the 3′ end of the genomic RNA) was predicted to consist of an unpaired A at position 62 and the base-paired nt 63 to 65 (CAC) (Fig. 1A). In a WNV infectious clone, one or more of the four nucleotides of the major eEF1A binding site were changed (Fig. 1). In mutant A, the unpaired A62 was substituted with a U, changing the binding site to 3′-UCAC-5′ (mutations are indicated in boldface in the text) and creating a G-U base pair that removed the bulge and further stabilized the stem in this region. In mutant B (3′-AGGU-5′), three of the four binding site nucleotides were changed. This mutation was predicted to widen the bulge by one nucleotide on each side but to maintain the base pairing of the two 5′ mutated nucleotides of the binding site. In mutant C (3′-AGGU-5′ plus 3′-ACCG-5′), the nucleotides on the opposite side of the stem from the binding site were mutated in mutant B RNA to restore the predicted secondary structure. In mutant D (5′-UGUG-3′), only the four binding site nucleotides were changed. The parental predicted secondary structure was preserved, but the unpaired nucleotide in the binding site was now a G instead of an A (Fig. 1A). WNV 3′(+) RNA probes with the mutant B or C substitutions were previously reported to decrease the in vitro binding of purified BHK eEF1A by about 60% in filter binding studies (3). The parental and mutant viral RNAs were in vitro transcribed by SP6 RNA polymerase and used to transfect 90%-confluent BHK monolayers in a six-well tissue culture plate. At 72 h after transfection, the plaque phenotype of progeny virus was assessed on an agarose-overlaid transfection well.

FIG. 1.

Mutation of the major eEF1A binding site in the 3′(+) SL of a WNV infectious clone. (A) The engineered nucleotide substitutions are indicated by black circles and revertant nucleotides are indicated with stars. (B) Plaques produced by progeny virus 72 h after transfection with parental or mutant B, C, or D or engineered revertant 2 RNA or 72 h after infection with revertant 1 (Rev 1) or Rev 2 virus. (C) Mutant virus growth in BHK and C6/36 cell monolayers infected at an MOI of 0.1. (D) Revertant virus growth in BHK and C6/36 cells infected at an MOI of 0.1. Error bars represent the standard error (SE) (n = 4). (E) Predicted secondary structures of mutant B (Mut B) and Mut C revertant 3′(+) SL RNAs.

No plaques were observed in wells transfected with mutant A or after three sequential blind passages of culture fluid harvested from transfection wells of BHK cells. Also, viral RNA was not detected by RT-PCR in any of these fluids. Mutants B, C, and D each produced pinpoint plaques (less than 0.1 mm in diameter) on the transfection plate (Fig. 1B). The diameters of plaques produced by parental virus were 2 to 3 mm (Fig. 1B). The titer of virus harvested from replicate nonoverlaid transfection plates was determined by plaque assay and this virus was then used to analyze virus kinetics in both mammalian (BHK) and mosquito (C3/36) cell lines. The growth of mutant viruses B, C, and D was reduced by 100- to 1,000-fold compared to that of the parental infectious clone virus. The titer at 48 h after infection of BHK cells was 3.5 × 104 PFU/ml for mutant B, 9 × 104 PFU/ml for mutant C, 4.35 × 104 PFU/ml for mutant D, and 5.5 × 107 PFU/ml for the parental infectious clone virus (Fig. 1C). These mutants also displayed a 10,000-fold reduction in growth in C6/36 cells. In these cells, the titer at 72 h was 2 × 103 PFU/ml for mutant B, 4 × 103 PFU/ml for mutant C, 3 × 103 PFU/ml for mutant D, and 1.2 × 107 for the parental infectious clone virus (Fig. 1C).

After three passages in either BHK or C6/36 cells, some intermediately sized plaques (1 mm in diameter) were observed among the pinpoint plaques with mutants B, C, and D. Intermediately sized plaques were individually picked, virus from each picked plaque was amplified by growth for 48 h in individual wells of a 24-well tissue culture plate, and then viral RNA in harvested culture fluid was extracted and amplified by RT-PCR. The PCR products were cloned into pTOPO-TA 2.1 (Invitrogen), and 10 clones for each mutant were sequenced. Analysis of the sequences showed that reversion to the parental nucleotide (C) had occurred in the intermediate plaque virus from mutants B, C, and D at either position 63 or position 65. The two types of partial revertants were found in approximately equal frequencies for each of the three mutants. The predicted RNA structures of the two revertants obtained for mutant D are shown in Fig. 1A (revertants 1 and 2). The growth kinetics of the two mutant D partial revertants were next compared in BHK and C6/36 monolayers infected at an MOI of 0.1 These revertant viruses maintained an intermediately sized plaque phenotype during passage. Although both revertants replicated significantly more efficiently than the original mutant D, neither revertant produced wild-type yields. The plaque and growth characteristics of these revertants remained stable during three additional passages. The virus titer produced in BHK cells at 48 h after infection by revertant 1 was 4.3 × 107 PFU/ml, and that by revertant 2 was 3.9 × 107 PFU/ml, while parental infectious clone virus produced a yield of 8.8 × 107 PFU/ml (Fig. 1D). In C6/36 cells, the yields of revertant 1 and revertant 2 at 72 h after infection were 8 × 106 PFU/ml and 6 × 106 PFU/ml, respectively, while the yield of the parental infectious clone virus was 1.2 × 107 PFU/ml (Fig. 1D).

To ensure that the increased replication efficiency observed for the partial revertants was not due to a second site mutation located elsewhere in the viral genomic RNA, site-directed mutagenesis was performed on mutant D plasmid DNA to engineer a partial revertant sequence (5′-UGUG-3′ changed to 5′-CGUG-3′). This mutant was designated engineered revertant 2 (Fig. 1A). After transfection, this RNA produced an intermediate plaque phenotype (1 mm) (Fig. 1B). Virus recovered from transfection wells was titered and used to infect either BHK or C6/36 cell monolayers at an MOI of 0.1. The virus yields were similar to those obtained with the original revertant 2 that arose in infected cells. The engineered revertant 2 produced 1.5 × 107 PFU/ml at 48 h after infection in BHK cells and 8.8 × 106 PFU/ml at 72 h in C6/36 cells. These results indicate that the phenotype of the revertant 2 virus was due solely to the reversion of a single C within the major eEF1A binding site.

In the case of mutant D, the two revertant Cs replaced Us and changed a U-G base pair back to a stronger G-C base pair. The predicted secondary structures of the mutant B and mutant C revertants are shown in Fig. 1E. In the mutant B revertant 1, the G·G bulge was replaced with a G-C base pair, and in mutant B revertant 2, the G-U base pair reverted to a G-C base pair. In mutant C, the two revertant Cs changed the more stable G-C and U-A base pairs to C·C and C·A bulges, respectively. While the reversions found in mutants B and D were predicted to stabilize the predicted RNA secondary structure in the major eEF1A binding site, the reversions found for mutant C destabilized the predicted secondary structure in this binding site. The lack of correlation observed between the stability of the stem in the region of the major eEF1A binding site (nt 63 to 65) and the efficiency of virus growth strongly suggests that the revertant Cs are important for another function.

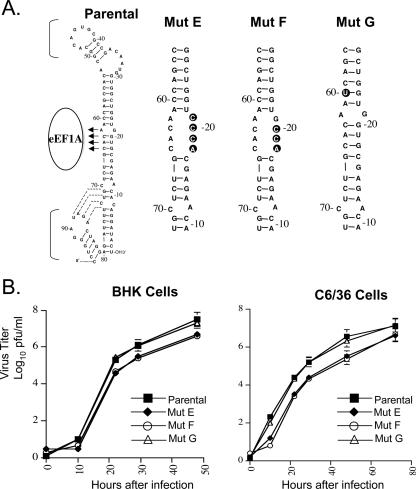

Mutagenesis of the nucleotides base paired with the major eEF1A binding site.

A previous study showed that when the pairing partners of the major eEF1A binding site nucleotides were mutated so that the binding site nucleotides were in a single-stranded context, the resulting mutant RNA bound about 20% more efficiently to eEF1A than did the wild-type 3′ SL RNA (3). The same set of substitutions and another similar set of mutations were introduced into the infectious clone. nt 18 to 21 were mutated to 3′-ACCC-5′ (mutant E) and nt 18 to 20 were mutated to 3′-ACC-5′ (mutant F) (Fig. 2A), and the effect of these mutations on virus growth efficiency was analyzed. After transfection of BHK monolayers with either mutant E or mutant F viral RNA, the plaque phenotype of the progeny virus was similar to that of the parental infectious clone virus (2 to 3 mm). Analysis of the growth of these mutant viruses in BHK and C6/36 cell monolayers infected at an MOI of 0.1 (Fig. 2B) showed that both mutants grew about 10-fold less efficiently than the parental virus. At 48 h after infection in BHK cells, mutant E produced a titer of 7 × 106 PFU/ml, mutant F produced a titer of 6 × 106 PFU/ml, and the parental infectious clone virus produced a titer of 5.5 × 107 PFU/ml. At 72 h after infection in C6/36 cells, mutant E produced a titer of 6 × 106 PFU/ml, mutant F produced a titer of 6.6 × 106 PFU/ml, and the parental virus produced a titer of 1.5 × 107 PFU/ml.

FIG. 2.

Mutation of the pairing partners of the major eEF1A binding site nucleotides. (A) The engineered nucleotide substitutions are indicated by black circles. (B) Virus growth in BHK and C6/36 cells infected at an MOI of 0.1. Error bars represent the SE (n = 4). Mut, mutant.

Mutagenesis of a C adjacent to the major eEF1A binding site.

The equivalent frequencies with which the same two partial revertants were generated after passage of mutants A, B, and C and the observation that either of the two Cs in the 4-nt binding site increased the efficiency of viral growth in cell culture to similar levels suggest that there is a redundancy in this binding sequence. To determine whether substitutions of other cytidines in the vicinity of the major eEF1A binding site would also have a negative effect on viral growth, the C located just above the major eEF1A binding site at nt 60 from the 3′ end was mutated to a U (mutant G) to maintain base pairing (Fig. 2A). Mutant G produced wild-type plaques (2 to 3 mm) at 72 h after RNA transfection (data not shown), and the virus yields observed after infection of BHK and C6/36 cell cultures with mutant G at an MOI of 0.1 were similar to those obtained with parental infectious clone virus. At 48 h after infection in BHK cells, parental virus produced a titer of 5.5 × 107 PFU/ml, while the yield for mutant G virus was 3.7 × 107 PFU/ml (Fig. 2B). At 72 h after infection in C6/36 cells, the yield for the mutant G was 1.2 × 107 PFU/ml, while that for the parental virus was 1.5 × 107 PFU/ml. In contrast to what was seen for the two conserved Cs in the eEF1A binding site, mutation of the C in mutant G had no observable effect on the efficiency of virus replication.

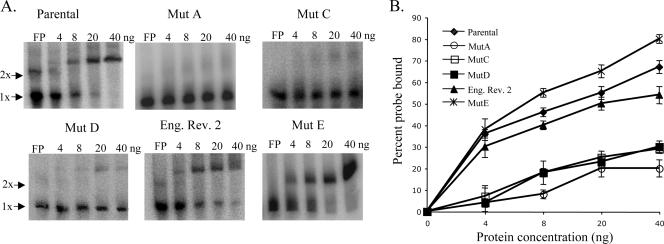

Relative binding activity of eEF1A for mutant SL RNAs.

Although the relative binding efficiencies for WNV 3′(+) SL RNA probes with mutant B, C, and F substitutions had been previously analyzed in filter binding assays, the binding efficiencies of eEF1A to the 3′(+) SL RNAs with mutant A, mutant D, mutant E, and the engineered revertant 2 substitutions had not been previously reported. A gel mobility shift assay was used to compare the relative binding activities of purified recombinant eEF1A for the various mutant 3′(+) SL RNAs and the parental 3′(+) SL RNA. Each of the radiolabeled 3′(+) SL RNA probes (2,000 cpm) was incubated with 0, 4, 8, 20, or 40 ng of purified recombinant eEF1A for 30 min at room temperature. The RPCs formed were separated on 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels and detected by phosphorimaging. The percentage of the free probe shifted was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. A representative gel from at least three replicate assays with each RNA probe is shown in Fig. 3A. Relative binding activity, as measured by the percentage of the free probe shifted by recombinant eEF1A for each of the RNA probes, is shown in Fig. 3B. With 40 ng of recombinant eEF1A, 67% of the parental 3′ SL RNA probe was shifted, but only 20% of the mutant A probe, 27% of the mutant C probe, 30% of the mutant D probe, and 54% of the engineered revertant 2 RNA probe were shifted. In contrast, 80% of the mutant E RNA probe was shifted with 40 ng of recombinant eEF1A. The results obtained with the gel mobility shift assays with mutant A, mutant C, mutant D, and mutant E 3′(+) SL RNAs correlated well with those obtained previously with filter binding assays (3). In the case of mutants A, C, and D, the relative decrease in the binding efficiency correlated with the observed decrease in viral replication efficiency. Also, the increased binding efficiency of the engineered revertant 2 RNA compared to what was seen for mutant C and D RNAs correlated with the observed increase in virus replication efficiency. Only with mutant E was there a lack of correlation between the eEF1A binding efficiency and the virus replication efficiency observed.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the binding activities of recombinant eEF1A for parental, mutant, and revertant virus 3′(+) SL RNA probes. (A) A gel mobility shift assay done with 32P-radiolabeled 3′(+) SL RNAs (2,000 cpm) and recombinant eEF1A purified from E. coli extracts. (B) The percentage of 32P-labeled RNA shifted by recombinant eEF1A. Error bars represent the SE (n = 3). Mut, mutant; Eng. Rev. 2, engineered revertant 2.

Effect of eEF1A binding site mutations on viral RNA translation.

All of the mutations made in the major eEF1A binding site reduced viral growth efficiency in cell culture. These mutations could negatively affect viral RNA translation and/or replication. To analyze the effect of mutations on viral RNA translation, parental infectious clone and mutant A, D, and E RNAs were in vitro transcribed and used to transfect BHK cells grown on coverslips. At 3 h after RNA transfection, the cells were fixed and permeabilized. WNV antigen was detected by immunofluorescence using an anti-WNV MHIAF as described in Materials and Methods. Even though the phenotypes of these mutants differed, for mutant A (lethal), mutant D (0.1-mm plaques), and mutant E (2- to 3-mm plaques), similar high levels of virus-specific antigen were detected in over 80 to 90% of the cells with the parental infectious clone RNA and also with each of the three mutant RNAs (Fig. 4A and B). These results indicate that none of these mutations significantly affected the translation efficiency of the viral RNA.

FIG. 4.

Effect of mutations in the major eEF1A binding site on the translation and replication efficiency of the viral genome RNA. (A) WNV proteins in BHK cells 3 h after the transfection of genomic RNA were detected by confocal microscopy using anti-WNV MHIAF (red). Mut, mutant. (B) Relative fluorescence intensities of WNV proteins in the cytoplasms of transfected BHK cells. (C) Relative quantification of intracellular WNV genomic RNA by real-time RT-PCR. Genomic RNA levels detected at 48 and 72 h after transfection are expressed as log10 changes (n-fold) in relative quantification units compared to the level of viral RNA present 6 h after transfection. Each RNA sample was normalized to cellular GAPDH mRNA. Error bars represent the SE (n = 3). E. Rev. 2, engineered revertant 2. (D) Relative quantification of intracellular WNV minus-strand RNA by strand-specific real-time RT-PCR. Minus-strand RNA levels detected at 12, 24, and 48 h after transfection are expressed as log10 changes (n-fold) in relative quantification units compared to viral RNA levels detected at 2 h after transfection. Each RNA sample was normalized to cellular GAPDH mRNA. Error bars represent the SE (n = 3). (E) Standard curve for the WNV minus-strand RNA real-time RT-PCR assay. CT values were obtained for 10-fold serially diluted viral plus- and minus-strand RNAs over the range of 1 × 108 to 1 × 103 copies in triplicate experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviation. (F) Schematic of a WNV NY99 reporting replicon containing an Rluc reporter gene fused in frame with the viral ORF (RlucRep). (G) Equal amounts of wild-type (black bar) and mutant (white bar) RlucRep RNAs (10 μg) were transfected into BHK cells, and cell lysates were quantified for Rluc activity at 2 h and 72 h posttransfection as a measure of viral RNA translation and replication, respectively. Average values obtained from four independent experiments are shown.

Effect of eEF1A binding site mutations on viral RNA replication.

The effect of mutations in the major eEF1A binding site on viral RNA replication was next assayed. Relative real-time RT-PCR was used to quantify the intracellular levels of genomic viral RNA within BHK cells 48 and 72 h after transfection. Viral RNA levels measured at each of these times were expressed as the amount (n = fold) of change compared to the amount of viral RNA present in cell extracts at 6 h after transfection and were normalized to the levels of the cellular GAPDH mRNA. Increases in the levels of viral genomic RNA above that of transfected input RNA were observed at 48 and 72 h after transfection with the parental infectious clone RNA (Fig. 4C). At both 48 and 72 h after the transfection of mutant A (lethal) RNA, the intracellular genomic RNA levels were lower than the viral RNA input at 6 h after transfection, indicating some degradation of the input RNA and little if any RNA replication (Fig. 4C). With mutant D, the level of genomic RNA produced was also lower than the level of input RNA at 48 h after transfection but to a lesser extent than seen with mutant A, suggesting that some RNA replication had occurred. An increase observed at 72 h after transfection confirmed that this RNA was replicating but at a level lower than that of the parental infectious clone RNA. These results were consistent with the low virus yield and small plaque size observed with mutant D, as seen in Fig. 1. At 48 h, the level of engineered revertant 2 genomic RNA detected was similar to that observed after the transfection of mutant D RNA at 48 h, but by 72 h there was an increase in the engineered revertant 2 genomic RNA that was greater than that seen with mutant D. With mutant E, an increase in genomic RNA levels was observed at both 48 and 72 h after transfection, but the levels were lower than those observed with the parental infectious clone RNA (Fig. 4C). A mutant RNA with the conserved RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) GDD motif mutated was used to assess the kinetics of viral RNA decay by real-time RT-PCR. The replication-deficient GDD mutant showed relative decreases in RNA levels at 48 and 72 h after transfection similar to those observed with the lethal mutant A RNA. These results indicate that each of the major eEF1A binding site mutations had a negative effect on viral genomic RNA replication, whether or not they increased or decreased in vitro eEF1A binding efficiency.

The WNV 3′(+) SL RNA is thought to contain promoter elements for minus-strand RNA synthesis. The effects of the major eEF1A binding site mutations on viral minus-strand RNA synthesis were next investigated using minus-strand-specific real-time RT-PCR. The specificity of the viral minus-strand real-time RT-PCR assay was first assessed by using in vitro-transcribed plus- and minus-strand viral full-length RNAs to generate an absolute standard curve with the same primers used for the detection of viral minus-strand RNA in transfected cells (Fig. 4E). A cycle threshold (CT) score of 30 was observed for 1 × 104 molecules of minus-strand RNA, while 1 × 108 molecules of plus-strand RNA were required to give a CT score of 30. These results indicate that the primers used detected viral minus-strand RNA 10,000 times more efficiently than the viral plus-strand RNA and that the sensitivity of this assay was sufficient to detect minus-strand RNA, even though the level of minus-strand RNA is about 100-fold lower than the level of plus-strand RNA in flavivirus-infected cells (11).

Intracellular levels of minus-strand RNA in BHK cells were quantified at 12, 24, and 48 h after transfection. Minus-strand RNA levels in each sample tested are shown as the amount of change (n = fold) compared to the level of viral RNA detected at 2 h after transfection and were normalized to cellular GAPDH mRNA. Since the majority of minus-strand signal detection at 2 h was due to the nonspecific detection of plus-strand input RNA, this calibration stringently removed nonspecific background. After transfection of parental infectious clone RNA, minus-strand RNA levels peaked at 24 h and then decreased by 48 h (Fig. 4D). No minus-strand RNA amplification was detected for mutant A (lethal) RNA at 12, 24, or 48 h after transfection (Fig. 4D). A decreased level of minus-strand synthesis was observed after the transfection of mutant D RNA compared to what was seen for the parental RNA. With engineered revertant 2, an intermediate level of minus-strand synthesis was detected; this level was between those for the parental and mutant D RNAs (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, mutant E, which bound to eEF1A more efficiently in vitro, showed a significantly increased level of minus-strand synthesis at 12, 24, and 48 h after transfection compared to what was seen for the parental infectious clone RNA, even though the amount of mutant E genomic RNA synthesis detected was lower than that of the parental infectious clone RNA (Fig. 4C and D). All of the mutations in the major eEF1A binding site that reduced in vitro RNA-protein binding activity also reduced the in vivo synthesis of minus-strand RNA. In contrast, a mutation that increased in vitro RNA-protein activity also increased in vivo minus-strand RNA synthesis.

As an alternate means of analyzing the effect of mutations in the major eEF1A binding site on viral RNA translation and replication, a WNV NY99 luciferase-reporting replicon (RlucRep; Fig. 4F) was used. RlucRep contains an Rluc gene fused in frame with the viral nonstructural gene ORF. The reporter gene was inserted into the position where the majority of the viral structural gene region had been deleted (Fig. 4F). After transfection of BHK cells with RlucRep RNA, two distinct Rluc peaks were detected, one at 2 to 10 h after transfection and another beginning at 24 h after transfection. The initial peak represents translation from the input RNA, while the second peak represents translation from replicated replicon RNA (31). After the transfection of BHK cells with equal amounts of either parental or mutant D RlucRep RNA, similar levels of Rluc activity were observed at 2 h after transfection, indicating that translation was not affected by the mutation (Fig. 4G). In contrast, at 72 h after transfection, a background level of Rluc activity was observed for the mutant D RlucRep (Fig. 4G). Also, an immunofluorescence assay was used to detect viral antigen-expressing cells. Antigen-positive cells were observed at 72 h after the transfection of BHK cells with the parental RlucRep RNA, but no positive cells were observed for cultures transfected with the mutant D RlucRep RNA (data not shown). The data show that in the replicon the mutant D substitutions caused a lethal phenotype. In contrast, although the mutant D infectious clone showed a reduced level of RNA replication (Fig. 4C and D), the levels of viral RNA replication were sufficient to generate a revertant (Fig. 1A).

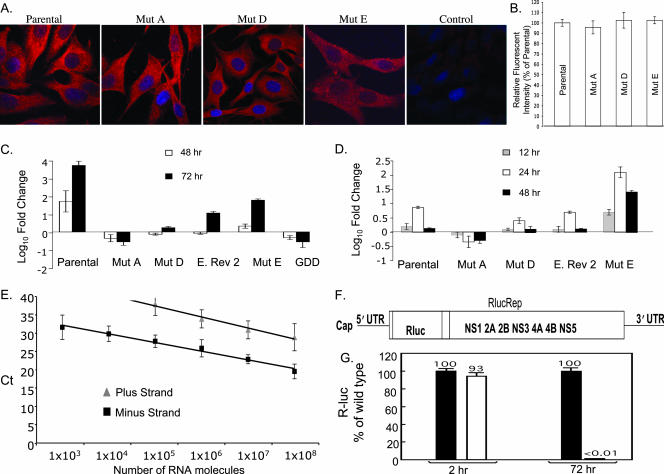

Colocalization of WNV proteins and eEF1A within BHK cells.

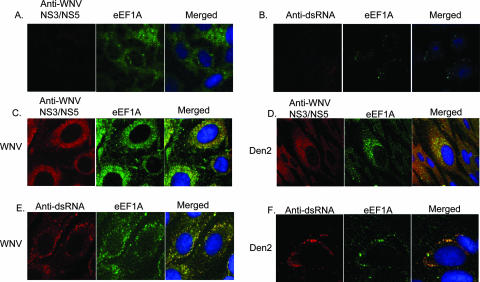

The observation that mutations made in the major eEF1A binding site in a WNV infectious clone RNA had a negative effect on viral growth suggested that this viral RNA-cell protein interaction occurred in infected cells. Previous studies indicated that foci in the perinuclear region detected by antibodies to various viral nonstructural proteins or dsRNA represented viral replication complexes (RCs) (33, 38, 59). Confocal microscopy was used to determine whether eEF1A and viral RCs colocalized in the cytoplasms of cells infected with either WNV or the divergent flavivirus Den 2. BHK cells were infected with WNV or Den 2 at an MOI of 0.1 or were mock infected. Cells grown on coverslips were fixed and permeabilized 36 h after infection with WNV or 72 h after infection with Den 2. Den 2-infected cells were fixed at a later time due to the slower growth kinetics of this virus. Anti-NS3/NS5 and anti-eEF1A were both used at a dilution of 1:200. Due to the high degree of conservation of NS3 and NS5 among divergent flaviviruses, antibodies made against WNV NS3/NS5 were used to detect RCs in both WNV- and Den 2-infected cells. In uninfected cells, eEF1A was found throughout the cytoplasm, and NS3/NS5 proteins were not detected (Fig. 5A). Although eEF1A was detected throughout the cytoplasm in infected cells, it was found to concentrate in discrete foci in the perinuclear region as well as in a ring around the nuclei in these cells. Colocalization of eEF1A and WNV NS3/NS5 proteins in a ring around the nucleus as well as in discrete foci was observed by 36 h after infection (Fig. 5C), and a similar pattern of colocalization in Den 2-infected cells was observed at 72 h after infection (Fig. 5D). The broad ring observed could be due to high levels of anti-eEF1A antibody or alternatively to the interaction of eEF1A and NS3/NS5 outside of the RCs. In subsequent experiments described below, done with a higher dilution of anti-eEF1A antibody (1:800), only the discrete perinuclear foci of eEF1A were detected (Fig. 5B, E, and F).

FIG. 5.

Colocalization of eEF1A and flavivirus RC in infected BHK cells. BHK cells were mock infected (A and B) or were infected with WNV strain Eg101 (C and E) or Den 2 strain Bangkok D80-100 (D and F) at an MOI of 0.1. Cells were fixed and permeabilized at 36 h (WNV) or 72 h (Den 2) and then incubated with a rabbit antibody specific for WNV NS3 and NS5 proteins at a 1:50 dilution (panels A, C, and D) or mouse monoclonal anti-dsRNA antibody at a 1:200 dilution (panels B, E, and F) and a goat polyclonal anti-eEF1A antibody at a 1:200 (panels A, C, and D) or a 1:800 (panels B, E, and F) dilution. The anti-NS3/NS5 and anti-dsRNA antibodies were both conjugated with secondary antibodies that fluoresced red, and the anti-eEF1A antibody was conjugated with a secondary antibody that fluoresced green. Hoechst dye was used to stain the nuclear DNA blue. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides, and cells were visualized using an LSM 510 laser confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY) with a 100× oil immersion objective. Yellow indicates colocalization.

Antibodies directed against dsRNA were also used in separate experiments to detect viral RNA in RCs. The anti-dsRNA antibody is specific for dsRNA and does not detect rRNA (Fig. 5B). In both WNV- and Den 2-infected cells, the colocalization of dsRNA and eEF1A was observed in perinuclear foci (Fig. 5E and F). The colocalization of eEF1A with two of the flavivirus nonstructural proteins, and also with dsRNA in infected cells, strongly suggests that eEF1A is recruited into viral RC in infected cells.

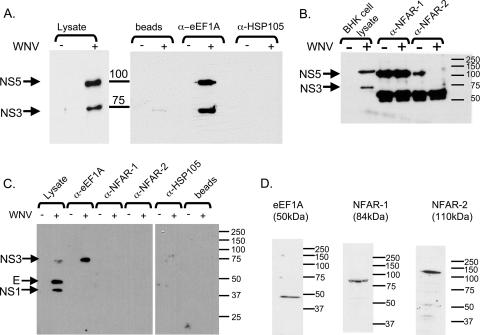

Coimmunoprecipitation of viral NS3 and NS5 by anti-eEF1A antibodies.

eEF1A was previously reported to bind to the viral nonstructural proteins of bovine viral diarrhea virus and hepatitis C virus and the polymerase and 3′ UTR of tobacco mosaic virus (24, 26, 60), and the colocalization experiments described above indicated that eEF1A might interact with one of the WNV nonstructural proteins. The WNV 3′(+) SL RNA is thought to contain promoter elements for minus-strand synthesis, but there has been no conclusive evidence that the viral polymerase and/or other viral RC proteins bind with high affinity to the 3′(+) SL RNA, even though this has been reported by other labs (9, 13). Antibodies against eEF1A were used in coimmunoprecipitation experiments to determine whether eEF1A was able to pull down WNV nonstructural proteins. The cellular proteins NFAR-1 and NFAR-2 were previously reported to bind to the 3′ terminus of bovine viral diarrhea virus genomic RNA (23). Antibodies to these proteins were also used in coimmunoprecipitation experiments. HSP105 was not previously reported to bind to any viral proteins, and antibody to this protein was used as a negative control. BHK cells were either infected with the parental infectious clone virus at an MOI of 5 or mock infected. S2 lysates were harvested and immunoprecipitated with antibodies against the cellular proteins eEF1A, NFAR-1, NFAR-2, and HSP105. The immunoprecipitated complexes were analyzed by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. NS3 and NS5 were detected in the infected but not in the uninfected cell lysates with an anti-NS3/NS5 antibody (Fig. 6A). WNV NS3 and NS5 were coprecipitated by anti-eEF1A antibody but not by anti-HSP105 antibody (Fig. 6A) or by anti-NFAR-1 or NFAR-2 antibodies (Fig. 6B). Since the anti-NFAR-1 and anti-NFAR-2 antibodies were generated in rabbits, as was the anti-WNV NS3/NS5 antibody, heavy- and light-chain antibody bands were detected in both uninfected and infected immunoprecipitates. Viral proteins in immunoprecipitates were also analyzed with a hyperimmune anti-WNV serum made in mice (MHIAF). In the infected cell lysate, NS1, E, and NS3 were detected on a Western blot with this antibody (Fig. 6C). NS3, but not E or NS1, was coprecipitated by anti-eEF1A antibody but not by NFAR-1, NFAR-2, or HSP105 antibody (Fig. 6C). Control Western blots performed on the cell lysates with the eEF1A, NFAR-1, and NFAR-2 antibodies detected only a single band of the expected size (Fig. 6D). When cell lysates were run on 1% agarose gels, no rRNA bands were detected by ethidium bromide staining, suggesting that polysomes were not present in the lysates. eEF1A interacts with one or more proteins present in WNV RCs. Although an interaction between eEF1A and either E or NS1 was ruled out, the observation that both NS3 and NS5 were coprecipitated strongly suggests that eEF1A interacts with one or more of the viral proteins in the RC. Since antibodies to the four other RC proteins, NS2A, NS2B, NS4A, and NS4B, were not available, it was also not possible to determine whether these proteins were also coprecipitated by eEF1A antibody.

FIG. 6.

Coimmunoprecipitation of WNV NS3 and NS5 with anti-eEF1A antibodies. (A) Antibodies against the cellular proteins eEF1A and HSP105 were incubated with WNV-infected or uninfected BHK cell lysates, and coprecipitated viral proteins were detected by Western blotting using anti-NS3/NS5 antibody. (B) Anti-NFAR-1 or anti-NFAR-2 was incubated with uninfected or infected BHK cell lysates, and coprecipitated viral proteins were detected by Western blotting using anti-NS3/NS5 antibody. (C) Anti-eEF1A, anti-NFAR-1, anti-NFAR-2, or anti-HSP105 antibody was used in pull-down experiments with WNV-infected or uninfected BHK cell lysates, and coprecipitated viral proteins were detected by Western blotting using anti-WNV MHIAF. (D) Proteins in BHK cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-eEF1A, NFAR-1, or NFAR-2 antibodies. α-, anti-.

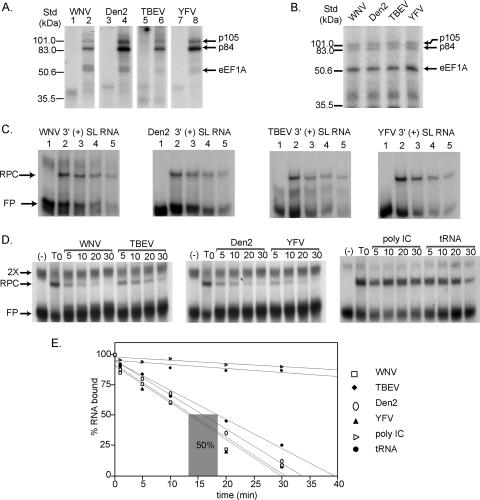

Cell proteins detected by divergent flavivirus 3′(+) SL RNAs.

Three cell proteins with molecular masses of 105, 87, and 52 kDa were previously found to bind specifically to the 3′(+) SL of WNV (2). The 52-kDa protein was identified as eEF1A, while the identities of the other proteins are not yet known. The SL structures formed by the 3′ (+) terminal sequences of the genomes of divergent flaviviruses are predicted to be conserved, even though only a few short sequences within these regions are conserved. Therefore, it was of interest to determine whether the same three cell proteins previously shown to bind to the WNV 3′-terminal structure would also bind to the 3′-terminal structures of other flaviviruses. 32P-labeled 3′(+) SL RNAs of Den 2, YFV, WNV, and TBEV were in vitro transcribed from cDNA clones as described in Materials and Methods and used as probes in UV-induced cross-linking assays with BHK S100 cytoplasmic extracts. YFV is the prototype of the flavivirus genus, and although both YFV and Den 2 are mosquito-borne viruses, their sequences are divergent from that of WNV. TBEV is a tick-borne flavivirus and is even more divergent. Cell proteins of 105, 84, and 52 kDa in uninfected BHK S100 cytoplasmic extracts bound to each of the 32P-labeled flavivirus 3′(+) SL RNAs tested when UV cross-linking was performed using 250 μJ (Fig. 7A) and 75 μJ (Fig. 7B). Although at 250 μJ the cross-linking efficiencies of the three different proteins varied with the various probes, the three proteins were detected with the WNV, Den 2, TBEV, and YFV probes (Fig. 7A). At 75 μJ, the three proteins bound with similar efficiencies to each of the RNA probes (Fig. 7B). The binding efficiency of eEF1A was consistently stronger at 75 μJ, while the 84-kDa protein showed the strongest binding at 250 μJ. These data suggest that the same set of BHK cytoplasmic proteins interacts with the 3′(+) SL RNAs of divergent flaviviruses.

FIG. 7.

Comparison of cell proteins binding to the 3′(+) SL RNAs of divergent flaviviruses. (A) BHK cell proteins in an S100 cell extract cross-linked to the 3′(+) SL RNAs of WNV, Den 2, TBEV, and YFV with either a high dose (250 μJ) or (B) a low dose (75 μJ) of UV light. Lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7, RNA probes incubated in the absence of cell extracts then digested with RNase; lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8, RNA probes incubated with cell extracts and then digested with RNase. (C) Gel mobility shift assays done with a constant amount of eEF1A (10 ng) and decreasing amounts of various flavivirus 32P-labeled 3′(+) SL RNA probes (20,000 cpm, 10,000 cpm, 5,000 cpm, and 2,500 cpm). The positions of the free probes (FP) and the RPCs are indicated. (D) The binding activity of eEF1A for divergent flavivirus 3′SL RNAs was assayed by competition gel mobility shift assay. Dissociation kinetics of preformed RPCs between eEF1A and 32P-WNV 3′(+) SL RNA after the addition of a 100-fold molar excess of one of the following cold competitors: WNV 3′(+) SL RNA, TBEV 3′(+) SL RNA, Den 2 3′SL (+) RNA, YFV 3′(+) SL RNA, poly(I-C), or tRNA. The time (min) a competitor was incubated with the RPC is indicated above the lanes. The positions of the free probe (F), a dimer probe (2X), and the RPC are indicated. (E) Graphic representation of the kinetics of RNA-protein dissociation. The percentage of RNA bound was plotted against the time that the competitor was incubated with the preformed RPC. The best-fit line for each data set was determined by linear regression. The range of time required for the different flavivirus 3′SL RNA competitors to cause 50% dissociation of the eEF1A/WNV 3′SL RPCs is indicated by a gray box. std, molecular mass standard.

Comparison of the relative binding activities of divergent flavivirus 3′(+) RNAs for eEF1A.

A probe titration gel mobility shift assay was performed to compare the relative binding affinities of the different flavivirus 3′ (+) SL RNAs for eEF1A. The concentration of each flavivirus 3′(+) SL RNA probe was varied (20,000, 10,000, 5,000 and 2,500 cpm), and the amount of purified BHK eEF1A (10 ng) was kept constant (Fig. 7C). eEF1A shifted each of the 32P-labeled (+) 3′SL RNA probes to similar extents (Fig. 7C).

A competition gel mobility shift assay was used to quantify the relative binding activity of purified BHK eEF1A for each of the flavivirus 3′(+) SL RNAs. Purified BHK eEF1A (10 ng) was preincubated with 32P-labeled WNV 3′(+) SL RNA (10,000 cpm) in binding reaction mixtures for 15 min. At different times after this preincubation period, approximately 20 ng of one of the following unlabeled competitors was added to the reaction: WNV 3′(+) SL RNA, Den 2 3′(+) SL RNA, TBEV 3′(+) SL RNA, YFV 3′(+) SL RNA, poly(I-C), or tRNA. The competitors were incubated in the binding reaction at 0, 5, 10, 20, and 30 min after the addition of a competitor. The RPCs and free probe were separated by nondenaturing PAGE (Fig. 7D). The amount of RPC remaining after each time interval was quantified by calculating the percentage of RNA shifted. The rate of complex dissociation in the presence of each competitor is shown in Fig. 7E. Each of the different flavivirus 3′(+) SL RNA competitors completely dissociated the complex between eEF1A and the 32P-labeled WNV 3′(+) SL RNA probe in less than 30 min, while neither of the nonspecific RNAs appreciably dissociated the RPC during the same time period, indicating that the dissociation observed was specific. The time required for each of the flavivirus 3′(+) SL RNA competitors to dissociate 50% of the RPC varied between 13 and 18 min. The WNV 3′(+) SL RNA competitor gave the fastest dissociation time (13 min), followed by YFV 3′(+) SL RNA (14 min), Den 2 3′(+) SL RNA (16 min), and TBEV 3′(+) SL RNA (18 min). These results confirm that eEF1A binds efficiently to the 3′ RNAs of divergent flaviviruses.

DISCUSSION

The 3′-terminal 96 nt of the WNV genomic RNA were predicted to form two adjacent SL structures, which were confirmed by structure-probing experiments; these structures are predicted to be conserved among divergent flaviviruses (6, 22, 40, 58). One major and two minor binding sites for the cellular protein eEF1A within the 3′-terminal 96 nt of the WNV genomic RNA were previously mapped (3). One of these minor binding sites is located in the top left loop (nt 41 to 47 from the 3′ end) of the 3′-terminal SL, while the other is in the small adjacent SL (nt 81 to 96), (3). The majority of the primary sequences and predicted structures of the two minor binding sites are conserved among divergent mosquito-borne flaviviruses. Previous studies showed that mutation of the top left loop of the 3′-terminal SL in an infectious clone or a replicon negatively affected virus growth or viral RNA replication, respectively (17, 53). Mutation or deletion of the small SL also negatively affected viral growth and viral RNA replication (W. G. Davis and M. A. Brinton, unpublished data). These studies indicate that both of the eEF1A minor binding sites are functionally important.

In the present study, the functional relevance of the major eEF1A binding site, which accounts for 60% of the in vitro eEF1A binding activity, was analyzed. The major eEF1A binding site consists of four adjacent nucleotides (nt 62 to 65, 3′-ACAC-5′) located on the 5′ side in the middle region of the stem of the 3′-terminal structure. A62 is unpaired, while nt 63 to 65 (CAC) are base paired. Substitution of A62 with a U to create a G-U base pair was lethal for the virus, and in vitro eEF1A binding activity to an RNA probe with this mutation was reduced by 40% compared to that for the parental SL RNA, suggesting that a bulge in this region is essential for both virus viability and efficient eEF1A binding. In a previous study, two alternative substitutions that caused A62 to be base paired, the substitution of A62 with C or the substitution of the G on the opposite side of the stem with a U, were also suggested to be detrimental to virus viability (62). The presence of a bulge may facilitate the opening of the major groove of the RNA stem, allowing sequence-specific binding of eEF1A to occur (57).

Mutations engineered into mutant B introduced an extra bulged nucleotide at position 63, while nt 64 and 65 remained base paired. Mutations made in mutants C and D to nt 62 to 65 maintained the predicted base pairing of these nucleotides but altered their primary sequence. Mutants B, C, and D produced viral yields that were 1,000-fold lower than that of the parental virus at 48 h after infection in mammalian cells and 10,000-fold lower at 72 h in mosquito cells. 3′(+) SL RNA probes containing mutant C or D substitutions showed a 40% or 37% decrease in relative binding activity to eEF1A, respectively, compared to that of the parental SL RNA. Partial revertants were found when all three of these mutants were passaged in BHK cells, and all of these had revertant Cs at either nt 63 or nt 65. These revertant Cs were in either a double-stranded (mutant B and D revertants) or a single-stranded (mutant C revertants) context. Although reversion of a C at either nt 63 or nt 65 resulted in an almost 1,000-fold increase in viral titers in both BHK and mosquito cells, these partial revertants grew about twofold less efficiently than the parental virus. The binding efficiency of eEF1A for a partial revertant RNA (engineered revertant 2) was 13% less efficient than that for the parental RNA. Also, the amount of minus strand produced by mutant D was reduced by 3-fold compared to parental RNA, and that produced by engineered revertant 2 was reduced by 1.5-fold. These results indicate that a C at nt 63 or 65 allows eEF1A binding of an efficiency sufficient to facilitate virus replication levels that are only slightly lower than when Cs are present at both of these positions and suggest that two adjacent functional eEF1A binding sites may be present in the major binding site in the WNV 3′(+) SL RNA. This redundancy may be an advantage in protecting this critical site from being inactivated by random mutations.

The extent of the decrease in the in vitro binding activity of eEF1A to a particular mutant WNV 3′(+) SL RNA consistently correlated with the extent of the decrease observed in the level of viral intracellular minus-strand RNA produced by an infectious clone with the same mutation. When a decrease in intracellular viral genomic RNA was detected, a decreased virus yield was also observed. Conversely, mutant E 3′(+) SL RNA bound 13% more efficiently to eEF1A in vitro than the parental RNA probe, and 10-times-higher levels of intracellular viral minus-strand RNA were observed for transfected cells. In flavivirus-infected cells, the levels of plus- and minus-strand RNA synthesis are tightly regulated. After the initial phase of RNA replication, the ratio of plus- to minus-strand RNA in infected cells is about 100 to 1 (11). Disregulation of this ratio by increased production of minus-strand RNA by mutant E resulted in less-efficient synthesis of genomic RNA and a reduced virus yield. Together, these results provide strong support for a direct role for eEF1A in the synthesis of WNV minus-strand RNA.

Extensive analyses of the interaction between the viral RdRp and the genomic template of the positive-strand RNA bacteriophage Qβ showed that this polymerase had binding pockets for both the genome 3′ and 5′ ends (44). The higher affinity of the 3′ end of the nascent minus-strand RNA for the 3′ binding pocket allowed it to replace the 3′ end of the genome template in this pocket, resulting in the nascent minus strand becoming a template for the initiation of plus-strand synthesis. One possibility is that the higher binding efficiency of eEF1A to the mutant E RNA increases the affinity of the 3′ end of the genome for the 3′ RdRp pocket, thus reducing the ability of the nascent minus-strand RNA to replace it in the 3′ pocket. This would result in an increase in minus-strand RNA synthesis and a decrease in plus-strand RNA synthesis.

eEF1A was found to colocalize with NS3, NS5, and dsRNA in both WNV- and Den 2-infected BHK cells. Also, anti-eEF1A antibody coimmunoprecipitated WNV NS3 and NS5 from infected cell lysates. It is not currently known whether eEF1A interacts directly with one or both of these proteins and/or with another RC protein, but these data suggest that eEF1A may interact with the viral RC as well as with the 3′(+) SL RNA. Previous studies with several other RNA viruses, including Qβ, vesicular stomatitis virus, bovine viral diarrhea virus, and hepatitis C virus have reported interactions between eEF1A and viral RC proteins (4, 10, 24, 26, 42). The roles of various host factors in facilitating Qβ RNA replication have been characterized (4). The bacterial homolog of eEF1A, EF-Tu, binds to the Qβ viral genomic RNA at the S2 binding site and also to viral proteins in the replication holoenzyme. Both of these interactions were reported to be required for the specific initiation of minus-strand RNA synthesis (7, 25). In contrast, the binding of eEF1A to the 3′ TLS of turnip yellow mosaic virus was shown to enhance translation and repress minus-strand RNA synthesis (35, 36). The data obtained in the present study support the hypothesis that for WNV, eEF1A is also involved in interactions with both viral RNA and protein and that these dual interactions facilitate the initiation of minus-strand synthesis.

Data obtained with purified poliovirus and hepatitis C virus RdRps suggest that these enzymes have a low affinity for their template RNAs (1, 32). The flavivirus RdRp, NS5, must recognize the 3′(+) and 3′(−) strand terminal RNA sequences to initiate the synthesis of viral minus- and plus-strand RNAs, respectively. NS5 has been reported to bind with high affinity only to the 5′(+) sequence of the viral genomic RNA as part of its RNA-capping function (15, 18, 63). eEF1A does not bind to the WNV 3′(−) SL RNA (M. Emara and M. A. Brinton, unpublished data) but does bind to the WNV 3′(+) SL RNA with high affinity (3), and the strength of this interaction consistently correlated with the efficiency of viral minus-stand RNA synthesis. Anti-eEF1A antibody was also shown to coimmunoprecipitate WNV RC proteins. These observations strongly suggest that eEF1A facilitates the interaction between the RdRp and the genome template and may assist in providing specific recognition of the 3′(+) SL by NS5. The three contact sites for eEF1A in the 3′(+) SL RNA each appear to be functionally important, suggesting that the binding of eEF1A to these three sites on the viral 3′(+) SL RNA may result in a conformation change in this RNA template and possibly also in the RC that is necessary for the RC to efficiently recognize, bind to, and correctly orient the template for the initiation of minus-strand RNA synthesis. The initiation of minus-strand RNA synthesis may be directly coupled with translation. The binding of eEF1A both to a newly made viral RC protein and to the 3′ end of a translating genomic RNA may facilitate the functional switching of a viral genome from translation to RNA replication.

eEF1A was shown to bind with similar efficiencies to the 3′(+) SL RNAs of four divergent flaviviruses. While the 3′-terminal genomic RNA sequences are not well conserved among these divergent flaviviruses, the RNA secondary structures as well as several short sequences, including the minor eEF1A binding sites, are conserved. Although the major binding sites for eEF1A on these divergent flavivirus RNAs have not yet been functionally mapped, eEF1A bound to the three other viral 3′(+) SL RNAs tested with an affinity similar to that to the 3′(+) SL of WNV. The data obtained in the present study suggest that a symmetrical internal bulge with a single C that is 1 to 3 nt below this bulge on the 5′ side in the middle region of the 3′-terminal stem appears to be all that is needed for efficient eEF1A binding at this site. There is a single-base, symmetrical, internal bulge with a C 1 or 2 nt below it on the 5′ side in the middle of the predicted 3′-terminal stems of the Den 2, YFV, and TBEV 3′(+) SL RNAs, supporting the presence of a similar major eEF1A binding site in each of these RNAs.

eEF1A was also found to colocalize with RCs in both Den 2- and WNV-infected cells. This observation provides additional support for a role for eEF1A in the synthesis of minus-strand RNA synthesis by all flaviviruses. Several characteristics of eEF1A make it an ideal protein to serve as a flavivirus host factor. eEF1A is constitutively expressed, distributed throughout the cytoplasm, and attached to actin filaments and so would be readily available for use by an incoming viral genome. After actin, eEF1A is the second most abundant protein in cells, and therefore competition between the viral RNA and the host cell for this protein would not be an issue. eEF1A is highly conserved among different eukaryotic species (12). Flaviviruses replicate in insect and a variety of vertebrate hosts during their natural transmission cycles, and the eEF1As available in these various hosts would be quite similar. During its normal cell functions, eEF1A interacts specifically with the other host elongation complex proteins, tRNAs, and rRNA. Both RNA-RNA and RNA-protein interactions may be functionally important for the role of eEF1A in flavivirus minus-strand RNA synthesis.

None of the mutations made in the major eEF1A binding site in either a WNV infectious clone or a replicon had any effect on the translation efficiency of the viral RNA. Data obtained in a previous study showed that the presence of the WNV 3′(+) SL on a chimeric reporter mRNA consisting of the WNV 5′ UTR and a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene cDNA gave a decreased in vitro translation efficiency compared to that of a mRNA with a 118-nt 3′ UTR from rubella virus. This decrease was observed with fresh reticulocyte lysates and high amounts of input RNA or with “old” lysates and lower amounts of input RNA (28). Under these conditions of limiting concentrations of translation factors, the high affinity of the 3′(+) SL RNAs for eEF1A (3) was postulated to allow competition of the 3′(+) SL RNA with tRNAs and ribosomes in vitro. However, the high abundance of eEF1A in cells makes it unlikely that eEF1A concentrations would be limiting. Colocalization of eEF1A with viral RCs was observed in infected cells. RCs are thought to be located within invaginations of perinuclear membranes (49). The observed concentration of eEF1A in areas with viral RCs would ensure continuing viral minus-strand synthesis even during periods of peak translation of viral proteins. Also, no effect on the translation efficiency of the viral polyprotein was observed in the present study in cells transfected with full-length viral RNAs with mutations that either increased or decreased eEF1A binding to the 3′(+) SL RNA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service research grant AI048088 to M.A.B. from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and by a Molecular Basis of Disease Fellowship from Georgia State University to W.G.D. The replicon work was partially supported by NIH grant Al065562 to P.-Y.S.

We thank Andrey A. Perelygin for cloning mutant D, Gertrud Radu for the Eg101 mutant GDD replicon, and Svetlana Scherbik and Mohamed Emara for technical advice and critical discussions of the data. We thank Mark Tilgner for construction and assaying of the mutant luciferase reporter replicon.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beckman, M. T., and K. Kirkegaard. 1998. Site size of cooperative single-stranded RNA binding by poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:6724-6730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackwell, J. L., and M. A. Brinton. 1995. BHK cell proteins that bind to the 3′ stem-loop structure of the West Nile virus genome RNA. J. Virol. 69:5650-5658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackwell, J. L., and M. A. Brinton. 1997. Translation elongation factor-1 alpha interacts with the 3′ stem-loop region of West Nile virus genomic RNA. J. Virol. 71:6433-6444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumenthal, T., and G. G. Carmichael. 1979. RNA replication: function and structure of Qbeta-replicase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 48:525-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bredenbeek, P. J., E. A. Kooi, B. Lindenbach, N. Huijkman, C. M. Rice, and W. J. Spaan. 2003. A stable full-length yellow fever virus cDNA clone and the role of conserved RNA elements in flavivirus replication. J. Gen. Virol. 84:1261-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinton, M. A., A. V. Fernandez, and J. H. Dispoto. 1986. The 3′-nucleotides of flavivirus genomic RNA form a conserved secondary structure. Virology 153:113-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, D., and L. Gold. 1996. RNA replication by Qβ replicase: a working model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11558-11562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Browning, K. S., J. Humphreys, W. Hobbs, G. B. Smith, and J. M. Ravel. 1990. Determination of the amounts of the protein synthesis initiation and elongation factors in wheat germ. J. Biol. Chem. 265:17967-17973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, C. J., M. D. Kuo, L. J. Chien, S. L. Hsu, Y. M. Wang, and J. H. Lin. 1997. RNA-protein interactions: involvement of NS3, NS5, and 3′ noncoding regions of Japanese encephalitis virus genomic RNA. J. Virol. 71:3466-3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cimarelli, A., and J. Luban. 1999. Translation elongation factor 1-alpha interacts specifically with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag polyprotein. J. Virol. 73:5388-5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleaves, G. R., T. E. Ryan, and R. W. Schlesinger. 1981. Identification and characterization of type 2 dengue virus replicative intermediate and replicative form RNAs. Virology 111:73-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Condeelis, J. 1995. Elongation factor 1 alpha, translation and the cytoskeleton. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20:169-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui, T., R. J. Sugrue, Q. Xu, A. K. Lee, Y. C. Chan, and J. Fu. 1998. Recombinant dengue virus type 1 NS3 protein exhibits specific viral RNA binding and NTPase activity regulated by the NS5 protein. Virology 246:409-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Alessio, J. A. 1982. RNA sequencing. IRL Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.