Abstract

The monoclonal antibody (MAb) 2G12 recognizes a cluster of high-mannose oligosaccharides on the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope glycoprotein gp120 and is one of a select group of MAbs with broad neutralizing activity. However, subtype C viruses are generally resistant to 2G12 neutralization. This has been attributed to the absence of a glycosylation site at position 295 in most subtype C gp120s, which instead is typically occupied by a Val residue. Here we show that N-linked glycans in addition to the one at position 295 are important in the formation of the 2G12 epitope in subtype C gp120. Introduction of the glycosylation site at position 295 into three subtype C molecular clones, Du151.2, COT9.6, and COT6.15, did increase 2G12 binding to all three mutagenized gp120s, but at various levels. The COT9-V295N mutant showed the strongest 2G12 binding and was the only mutant to become sensitive to 2G12 neutralization, although very high antibody concentrations were required. Introduction of a glycosylation site at position 448 into mutant COT6-V295N, which occurs naturally in COT9, resulted in a virus that was partially sensitive to 2G12. Interestingly, a glycosylation site at position 442, which is common among subtype C viruses, also contributed to the 2G12 epitope. The addition of this glycan increased virus neutralization sensitivity to 2G12, whereas its deletion conferred resistance. Collectively, our results indicate that the 2G12 binding site cannot readily be reconstituted on the envelopes of subtype C viruses, suggesting structural differences from other HIV subtypes in which the 2G12 epitope is naturally expressed.

The monoclonal antibody (MAb) 2G12 is a broadly neutralizing antibody that recognizes a unique epitope on the surface of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) gp120 (39), as no other MAb is able to prevent its binding to gp120 and vice versa (31). Recent studies have shown that 2G12 binds to a cluster of high-mannose sugars, with α1→2 terminal mannose residues as essential components (36, 37). Furthermore, detailed mutagenesis studies on subtype B have implicated the N-linked glycans at positions 295, 332, and 392 in gp120 as being the most critical for 2G12 binding, with glycans at positions 339, 386, and 448 likely playing an indirect role (36, 37, 39). Crystal structures of Fab 2G12 and its complexes with high-mannose glycosides revealed that the two Fabs assemble into an unusual interlocked VH domain-swapped dimer (5). Computational modeling based on these crystal structures has suggested that 2G12 likely binds to glycans at positions 332 and 392 in the primary combining sites, with a potential interaction with the glycan at position 339 in the VH-VH′ binding interface (5). Based on this model, the glycan at position 295 is presumed to play an indirect role by preventing processing of the glycan at 332 and thus maintaining its oligomannose structure (5).

HIV-1 subtype C viruses have been shown to be largely insensitive to neutralization by 2G12 (3, 4, 14). A comparative analysis of HIV-1 subtype C and B sequences contained within the Los Alamos HIV database shows significant differences in the frequencies of an Asn residue at position 295 (88% in subtype B versus 12% in subtype C); the consensus for subtype C viruses at position 295 is a Val residue. These findings have led to speculation that the absence of a glycan at position 295 is responsible for the insensitivity of subtype C isolates to 2G12 neutralization (6, 14, 36). This notion was supported by a recent report showing that reintroduction of a glycan attachment site at position 295 into a subtype C gp120 protein expressed in baculovirus resulted in increased binding of 2G12 (6). However, the neutralization sensitivity of this glycan-enriched gp120 to 2G12 was not investigated.

A number of experimental observations suggest possible antigenic differences between subtype B and C envelope glycoproteins. First, the V3 region of subtype C envelopes is less variable than its subtype B counterpart, as reflected in the lower codon-specific nonsynonymous-to-synonymous-substitution ratio and lower covariability (10, 12). Rather, the gp120 segment downstream of V3 that overlaps the C3 region shows higher variability in subtype C viruses (10, 13). Second, studies on HIV-1 subtype C transmission pairs have shown that recipient viruses have fewer N-linked glycosylation sites and shorter V1-to-V4 regions in the envelope glycoproteins than do donor viruses (7, 41), which has not been observed with subtype B transmissions (9). Finally, natural infection with HIV-1 subtype C typically induces higher titers of autologous neutralizing antibody responses that are less cross-reactive than responses in subtype B-infected individuals (15, 22). Structural differences between the envelope glycoproteins of subtype B and C viruses may underlie these subtype-specific patterns of antigenic exposure. In this study, we examine some of the glycan requirements that influence the formation of the 2G12 epitope in the context of subtype C envelopes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, MAbs, and cell lines.

Three HIV-1 subtype C functional envelope clones were used. Du151.2 was obtained from David Montefiori (Duke University), and COT9.6 and COT6.15 were generated previously (14). The pSG3Δenv plasmid was obtained from Beatrice Hahn. Soluble CD4 and CD4-immunoglobulin G2 (CD4-IgG2) were generously provided by Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Tarrytown, NY). MAbs were obtained from the NIH AIDS Reference and Reagent Program and the IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Consortium. Plasma samples from HIV-1 subtype C-infected individuals (BB12, BB107, and IBU21) were purchased from the South African National Blood Service. The cell line JC53bl-13 was obtained from the NIH AIDS Reference and Reagent Program. 293T cells used for transfection were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Both cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. Cell monolayers were disrupted at confluence by treatment with 0.25% trypsin in 1 mM EDTA.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Specific amino acid changes in the envelope glycoproteins were introduced using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The presence of mutations was confirmed by sequence analysis using an ABI PRISM Big Dye Terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and an ABI 3100 automated genetic analyzer.

Generation of Env-pseudotyped virus stocks.

Virus stocks were generated by cotransfecting the Env plasmid with pSG3Δenv (40), using the Fugene transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Fifty percent tissue culture infective doses (TCID50s) were quantified by infecting JC53bl-13 cells with serial fivefold dilutions of the supernatant in quadruplicate in the presence of DEAE-dextran (30 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The infection was monitored 48 h later by evaluating the luciferase activity, using the Bright Glo reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's instructions. Luminescence was measured in a Wallac 1420 Victor multilabel counter (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT). The TCID50 was calculated as described previously (18). Wells with relative light unit readings of >2.5 times that of the negative control (mock infection) were considered positive.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting.

Pseudoviruses carrying the wild-type and V295N mutant envelopes were pelleted through a 30% sucrose cushion. Viral proteins were resolved in a Criterion 5% Tris-HCl gradient gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride-nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare Life Science, Piscataway, NJ). The membranes were blocked overnight with 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline, probed with the anti-gp120 antibody D7324, and then visualized with a horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-sheep antibody (Sigma) in conjunction with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare Life Science, Piscataway, NJ).

MAb binding to gp120 (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]).

gp120 molecules present in the supernatant were captured onto a solid phase via adsorbed antibody D7324. MAbs were bound to gp120 in 1% bovine serum albumin-0.05% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Bound antibodies were detected with alkaline phosphatase-conjugate anti-human IgG (Sigma) and followed by the AMPAK amplification system (Dako Diagnostics Ltd., Glostrup, Denmark).

MAb binding to envelope glycoprotein.

Flow cytometric analysis was performed to evaluate the binding of MAbs to the envelope glycoprotein on the surfaces of 293T cells transfected with an env-carrying plasmid as described elsewhere (16). 293T cells were transfected at 50% confluence with 5 μg of the env-carrying plasmid in a T25 flask. After 48 h, the cells were harvested, washed with PBS, and incubated with 20 μg/ml of MAb in a shaker at room temperate. After 1 h, the cells were washed and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde-60 mM sucrose-PBS, pH 7.4, for 15 min at room temperature (RT). The cells were washed in 20 mM glycine-PBS (solution A) and incubated in 1% bovine serum albumin-0.05% NaN3 in solution A (solution B) for 15 min at RT, after which 20 μl of anti-human IgG-fluorescein isothiocyanate (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) was added and incubated for 45 min at RT. After two additional washes with solution B, the stained cells were analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer. Live cells were initially gated by forward and side scatter. A total of 20,000 live cells were acquired for analysis. MAb binding was evaluated by a shift in the mean fluorescence at 575 nm compared to the negative control fluorescence. The data were analyzed using the Cell Quest program.

Single-cycle neutralization assay.

Neutralization was measured as a reduction in luciferase expression after a single-round infection of JC53bl-13 cells with Env-pseudotyped viruses (30). Briefly, 200 TCID50 of pseudoviruses in 50 μl was incubated with 100 μl of serially diluted MAbs, plasma, or soluble CD4 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum in a 96-well plate, in triplicate, for 1 h at 37°C. One hundred microliters of JC53bl-13 cells (1 × 104 cells/well) containing 75 μg/ml DEAE-dextran was added, and the cultures were incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Infection was monitored by evaluating the luciferase activity. Titers were calculated as the inhibitory concentration (IC50) or reciprocal plasma dilution causing a 50% reduction in the relative light units compared to the virus control level (wells with no inhibitor) after subtraction of the background (wells without virus infection). The subtype B pseudovirus QHO692.42, which is sensitive to neutralization by 2G12 and IgG1b12, was included as a positive control (23).

RESULTS

Introduction of an N-linked glycan at position 295 of gp120 results in increased 2G12 binding but not enhanced virus neutralization.

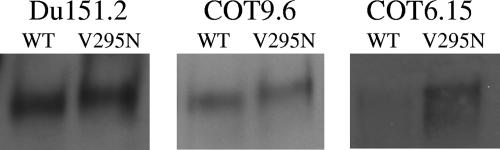

We previously characterized a number of subtype C viruses that were refractory to neutralization by MAb 2G12 (14, 24). In an attempt to reconstitute the 2G12 epitope on subtype C gp120, we first introduced a glycosylation site at position 295 by mutating Val to Asn in three previously studied subtype C envelope clones, namely, Du151.2, COT9.6, and COT6.15. These viruses have glycan attachment sites at positions 332 and 392 (393 in Du151.2) which, together with the glycan at position 295, are believed to be required for the formation of the 2G12 epitope (Fig. 1) (5, 36, 37). The incorporation of an extra glycan in all three viruses was confirmed by an increase in the molecular mass of each mutant relative to the parental gp120 (Fig. 2).

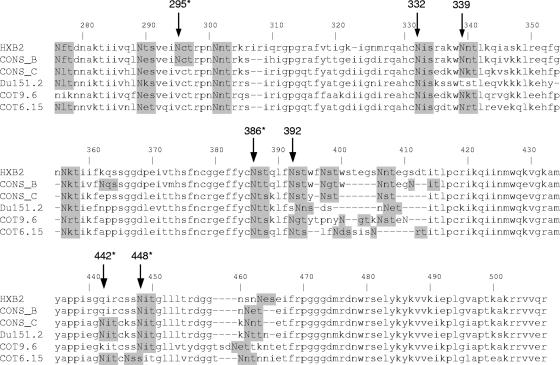

FIG. 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of C2-to-C5 region of gp120s of the three HIV-1 subtype C clones used in this study. Consensus subtype B and C sequences were aligned with the three subtype C envelope sequences and the HXB2 reference sequence. Potential N-glycan attachment sites, determined using N-Glycosite (http://hiv-web.lanl.gov/content/hiv-db/GLYCOSITE/glycosite.html), are highlighted in gray. The sites indicated with arrows, except for position 442, have been implicated in the formation of the 2G12 epitope. Those marked with asterisks were analyzed in this study. The N-linked glycosylation site at position 392 in Du151.2 is shifted by one amino acid. The env gene nucleotide sequences can be obtained from GenBank under accession numbers DQ447272 (Du151.2), DQ447266 (COT9.6), and DQ411851 (COT6.15).

FIG. 2.

Introduction of an N-glycan attachment site at position 295 in viruses Du151.2, COT9.6, and COT6.15 leads to an increase in molecular mass. The electrophoretic mobilities of virion-associated gp120s from the wild type (WT) and V295N mutants of Du151.2, COT9.6, and COT6.15 are shown on a 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. Western blots were visualized using the antibody D7324, an anti-sheep Ab conjugate, and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents.

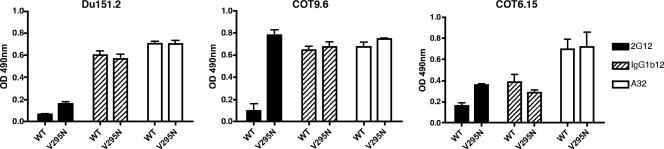

Antibody binding to wild-type and V295N mutant viruses was assessed by ELISA. There were no significant differences in binding levels between the wild-type and V295N mutant envelopes for control MAbs IgG1b12 and A32, indicating that the V295N mutation had not caused a substantial conformational change in the gp120s. In contrast to the case for the control MAbs, a distinct increase in 2G12 binding was observed. 2G12 binding to the COT9-V295N gp120 mutant was particularly pronounced, as a fivefold increase in optical density relative to that with wild-type gp120 was observed. For mutants Du151-V295N and COT6-V295N, there was an ∼2-fold increase in 2G12 binding (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

V295N mutation increases 2G12 antibody binding to subtype C gp120. The binding of MAbs 2G12 (10 μg/ml), IgG1b12 (10 μg/ml), and A32 (10 μg/ml) to the gp120s of Du151.2, COT9.6, and COT6.15, with and without a glycan at position 295, was measured by ELISA. The graphs represent the means for three separate experiments. OD, optical density.

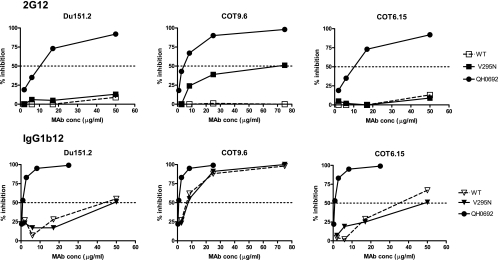

To determine if the increased binding of 2G12 to monomeric gp120 would result in enhanced neutralization, wild-type and mutant envelope genes were cotransfected with an env-deficient provirus to produce pseudotyped virus particles. Only the COT9-V295N mutant became sensitive to neutralization by 2G12. However, high antibody concentrations were required (IC50, 69 ± 6 μg/ml) (Fig. 4). No measurable increased sensitivity to 2G12 neutralization was observed for mutant viruses Du151-V295N and COT6-V295N, even at antibody concentrations of up to 100 μg/ml. Du151.2 contains N-linked glycosylation sites, at positions 332, 386, and 448, that form part of the 2G12 epitope. However, Du151.2 lacks glycan 339, which is considered to play an important supportive role (36, 37), and the potential N-linked glycosylation site at position 392 is shifted to position 393, which may impact the binding of 2G12 to the oligomannose cluster.

FIG. 4.

Neutralization of wild-type and V295N mutant subtype C envelope-pseudotyped viruses by 2G12. Results are shown as reductions of virus infectivity relative to that of the virus control (without MAbs), with 50% inhibition indicated by a horizontal dotted line. MAb IgG1b12 and virus QH0692 (subtype B) were used as positive controls.

These data suggest that only on COT9.6 was the 2G12 epitope reconstituted sufficiently well to allow high-affinity binding and neutralization by 2G12. There were no significant differences in neutralization by the IgG1b12 MAb between the mutant and wild-type variants. This demonstrates that the observed variation in 2G12 sensitivity was not the result of a general neutralization-sensitive phenotype of the mutant form and that the introduced mutation had not caused a substantial change in the quaternary conformation of the viral envelope spike (Fig. 4).

Introduction of an N-linked glycosylation site at position 448 further enhances 2G12 neutralization sensitivity.

The above results suggested that in addition to the glycan at position 295, further glycans at other positions may be required to form the 2G12 epitope on subtype C viruses. Some studies have suggested that the N-glycan at position 448 may be important for 2G12 recognition (36, 39). Since COT9.6 has an N-linked glycosylation site at position 448, whereas COT6.15 does not (Fig. 1), we hypothesized that the introduction of a glycosylation site at position 448 in COT6.15 and COT6-V295N might allow 2G12 to bind the gp120s of these viruses more efficiently and hence render these viruses sensitive to neutralization by this MAb.

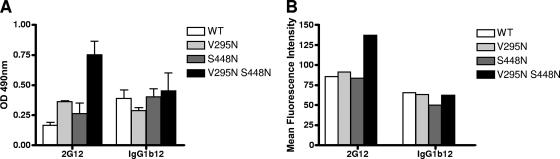

Introduction of a glycan attachment site at position 448 in the background of the COT6-V295N mutant (Ser448→Asn) indeed resulted in stronger binding of 2G12 to this gp120, as measured by ELISA and fluorescence-activated cell sorting, than 2G12 binding to wild-type gp120 and the single mutants V295N and S448N (Fig. 5). This increased binding to 2G12 also resulted in viruses that were marginally more sensitive to 2G12 neutralization, although like the case with the COT9-V295N mutant, relatively high antibody concentrations were required. The IC50 for mutant virus COT6-V295N/S448N was 65 ± 3 μg/ml. In contrast, wild-type COT6.15 and the COT6-V295N mutant were not neutralized even at antibody concentrations of up to 150 μg/ml (Table 1).

FIG. 5.

Impact of V295N and S448N mutations on 2G12 binding to monomeric and oligomeric gp120 from COT6.15. Antibody binding was evaluated by gp120 ELISA (A) and flow cytometric analysis (B) of the envelope protein expressed on the surfaces of transfected 293T cells. ELISA results are the averages for four independent experiments, and fluorescence-activated cell sorting results are from one experiment representative of three. OD, optical density.

TABLE 1.

Neutralization of wild-type virus and glycosylation mutants by MAbs, CD4-IgG2, and HIV-positive plasmas from subtype C-infected individualsa

| Virus and envelope glycoprotein | IC50

|

ID50

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2G12 | IgG1b12 | 4E10 | CD4-IgG2 | BB12 | IBU21 | BB107 | |

| COT9.6 | |||||||

| WTb | >100 | 3.2 | 3.88 | 0.08 | 426 | ND | 502 |

| 295N | 68.7 | 3.0 | 6.08 | 0.08 | 409 | ND | 464 |

| V295N K442N | 33.9 | 1.7 | 1.75 | 0.03 | 318 | ND | 460 |

| V295N K442N N386Q | >100 | 0.2 | 4.59 | 0.87 | 759 | ND | 1,000 |

| COT6.15 | |||||||

| WT | >150 | 23.3 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 469 | 391 | ND |

| 295N | >150 | 51.5 | 0.75 | 0.49 | 210 | 303 | ND |

| 448N | >150 | 29.5 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 437 | 398 | ND |

| V295N S448N | 64.5 | 35.2 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 367 | 393 | ND |

| V295N S448N N442Q | >150 | 37.8 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 728 | 557 | ND |

| V295N S448N N386Q | >150 | 1.6 | 0.58 | 1.32 | 325 | 338 | ND |

Values in bold indicate significant differences from the parental construct. ND, not determined (COT9.6 was insensitive to IBU21, and COT6.15 was insensitive to BB107, and hence these assays were not performed). IC50, concentration of MAbs or CD4IgG2 that reduces viral infectivity by 50%. ID50, dilution of plasma that reduces viral infectivity by 50%.

COT9.6 naturally harbors N448.

The N-linked glycan at position 442 plays a role in the formation of the 2G12 epitope in subtype C viruses.

A further difference between the COT6.15 and COT9.6 sequences is that COT6.15 has a glycosylation site at position 442, whereas in COT9.6 this site is absent due to the occurrence of a Lys residue (Fig. 1). Sequence analysis of HIV-1 envelope sequences contained within the Los Alamos HIV database (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/index) shows that an N-linked glycan attachment site at position 442 is relatively common among subtype C viruses (54%) but highly unusual among subtype B viruses (3%) (Fig. 1). To examine whether the presence of this glycosylation site influences the formation of the 2G12 epitope, we introduced a glycosylation site at position 442 in the COT9-V295N mutant and eliminated this site in the double mutant COT6-V295N/S448N described above. The COT9-V295N/K422N mutant showed increased binding to 2G12 relative to the wild type and the V295N single mutant (Fig. 6). Accordingly, the corresponding virus was more sensitive to neutralization by 2G12 (IC50, 34 ± 4 μg/ml) (Table 1). Removal of the N-linked glycosylation site at position 442 in virus mutant COT6-V295N/S448N rendered this virus resistant to neutralization by 2G12 (Table 1). Interestingly, only a slight decrease in binding to 2G12 was observed (Fig. 6). These results suggest that the glycan at position 442 indeed contributes to the formation of the 2G12 epitope in the context of subtype C envelope glycoproteins.

FIG. 6.

N-glycosylation at position 442 affects 2G12 and IgG1b12 binding to monomeric gp120. The ability of MAbs 2G12 (10 μg/ml) and IgG1b12 (10 μg/ml) to bind gp120s from the glycosylation mutants of COT9.6 (A) and COT6.15 (B) was assessed by ELISA. The graphs represent the means for three separate experiments. A32 and IBU21 were used to standardize the amount of gp120 bound to the plate (data not shown). The subtype B virus QH0692 was used as a positive control for 2G12 and IgG1b12 binding. OD, optical density.

Occurrence of the N-linked glycan at position 386 enhances sensitivity to 2G12 in subtype C viruses.

We next wished to determine whether the presence of the glycosylation site at position 386 is crucial to the formation of the 2G12 epitope in subtype C viruses, as it is in subtype B (36, 37). Therefore, we eliminated this glycosylation site by mutating Asn386 to Gln in mutant viruses COT9-V295N/K422N and COT6-V295N/S448N, in which the 2G12 epitope had been partially reengineered. The COT9-V295N/K442N/N386Q gp120 mutant showed a threefold reduction in 2G12 binding compared to COT9-V295N/K442N gp120 in ELISA (Fig. 6). For the COT6-V295N/S448N/N386Q mutant, no significant reduction in 2G12 binding was observed. Nevertheless, in both cases, deletion of the glycosylation site at position 386 resulted in resistance to 2G12 neutralization (Table 1). Interestingly, deletion of the glycan at position 386 also resulted in a >10-fold increase in neutralization sensitivity to IgG1b12 for both mutants (Table 1), without a corresponding increase in IgG1b12 binding to monomeric gp120 in ELISA (Fig. 6).

Variation in N-glycosylation also affects neutralization efficiency by MAb 4E10, CD4-IgG2, and HIV-positive plasma.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that the introduction or deletion of N-linked glycans in gp120 affects the exposure of certain neutralization epitopes, even when the epitope is not in the immediate vicinity of the site where the mutation is introduced (19, 29). In an effort to determine if other neutralization epitopes may have been affected by these changes in N-linked glycosylation sites, we evaluated the neutralization sensitivities of all the mutant viruses described above to MAb 4E10, CD4-IgG2, and HIV-1-positive plasma samples with broad cross-neutralizing activity from subtype C-infected individuals (BB12, BB107, and IBU21). The anti-gp41 neutralizing MAb 2F5 was not used, as most subtype C viruses, including these three, are insensitive to this MAb (3, 4, 14).

The introduction of a glycan at position 295 in COT6.15 and COT9.6 resulted in a twofold increase in IC50 for MAb 4E10 (Table 1), suggesting that this glycan may affect the exposure of the membrane-proximal region, as suggested by others (29). In the case of CD4-IgG2, there was a decrease in sensitivity to neutralization of subtype C viruses in which the glycosylation site at position 386 had been mutated to Gln (Table 1). As mentioned above, N386Q viral mutants showed increased sensitivity to IgG1b12. These contrasting effects on neutralization by CD4 binding site-directed agents suggest that removing the glycan at position 386 may affect the conformation of the CD4 binding site. However, whether this is specific to the Gln substitution was not assessed here and cannot be excluded. The COT9-V295N/K442N/N386Q mutant was also more sensitive to neutralization by two plasma samples, BB12 and BB107, than to the parental virus (Table 1). This difference was not observed for the COT6-V295N/S448N/N386Q mutant and plasma samples BB12 and IBU21. However, these plasmas were better able to neutralize the COT6-V295N/S448N/N442Q mutant, suggesting that the glycan at position 442 may shield certain neutralization epitopes on select subtype C envelopes.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that resistance of subtype C viruses to MAb 2G12 is not due solely to the absence of a glycan at position 295. While this glycan did partially contribute, further reconstitution of the 2G12 epitope required the presence of N-linked glycosylation sites at positions 448 and 442. The glycan at position 448 has previously been implicated in the 2G12 binding site (36, 39), while the glycan at position 442 may be a novel site for the 2G12 epitope in subtype C viruses. However, it should be noted that despite being able to confer 2G12 sensitivity, the antibody concentrations required to achieve neutralization of mutant viruses were at least 10-fold higher than those reported for subtype B viruses (3, 23). Collectively, these results point to possible differences in the structural conformation of subtype C envelope glycoproteins in the region of gp120 that involves the 2G12 epitope.

The N-linked glycan at position 295 is indispensable for the formation of the 2G12 epitope and is the most consistent factor determining the lack of sensitivity to 2G12 neutralization among subtype C viruses. As shown here, the introduction of an N-linked glycan at position 295 resulted in increased binding of MAb 2G12 to gp120s from all three subtype C viruses tested here. A similar finding was reported for a baculovirus-expressed subtype C envelope glycoprotein (6). However, increased binding did not necessarily result in neutralization, as only one of the three mutant viruses examined, COT9-V295N, became sensitive to 2G12. We hypothesize that the conformation of subtype C envelopes precludes the precise formation of the oligomannose cluster necessary for 2G12 binding to the functional envelope spike relative to its occurrence on subtype B viruses. This could be effected by, for example, differences in the processing of glycans between different subtypes. It should be noted that, to date, very little biochemical characterization of N-linked glycans in gp120 has been done (21, 43). More importantly, all analyses have been performed on subtype B gp120s, with no experimental evidence to suggest that subtype C envelopes display the same glycan composition as their subtype B counterparts. Clearly, similar studies using subtype C envelopes will need to be conducted to resolve this issue.

We confirmed that the N-linked glycan at position 448 is a determinant in the formation of the 2G12 epitope, as suggested previously (36, 39). Whether or not this site functions in an isolate-specific manner remains to be elucidated fully. Other studies have not always identified this site as important, including an analysis of 2G12 neutralization escape variants (32, 35).

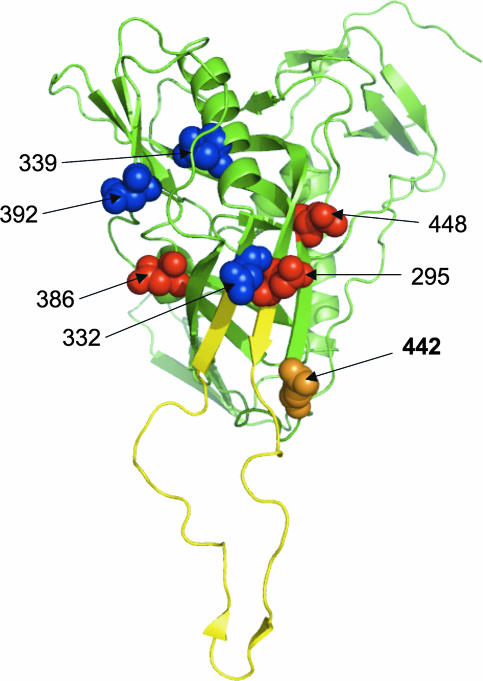

Our data provide strong evidence that glycosylation sites other than those described for subtype B viruses are required to form the 2G12 epitope on subtype C viruses. Thus, the presence of a glycosylation site at position 442, which is absent in subtype B envelopes, enhanced the binding and neutralization of a subtype C virus by MAb 2G12. This glycan is not in the immediate proximity of the putative 2G12 binding site involving the glycans at positions 332 and 392 (Fig. 7) (5) and therefore may define a new determinant for 2G12 binding in the context of subtype C gp120s. We have not explored if 2G12 binds directly to this glycan or whether it is a complex-type glycan rather than an oligomannose. Nevertheless, it is tempting to speculate that the glycan at position 442 may perform a function similar to that purported for the glycan at position 295 in subtype B viruses, namely, preventing glycosidase trimming of oligomannose clusters (5). Mutants in which this glycan was deleted showed increased neutralization sensitivity to polyclonal HIV-positive sera (Table 1). Given the close proximity of this glycan to the V3 loop (Fig. 7), it may serve to protect the V3 region from neutralizing antibodies. The more frequent occurrence of this glycan among subtype C gp120s than among subtype B gp120s could contribute to the lower levels of variation seen in subtype C V3 sequences (10). However, detailed studies are needed to address this hypothesis directly.

FIG. 7.

Location of the Asn at position 442 relative to the location of the V3 loop region and other N-glycans involved in 2G12 binding. The gp120 molecule is viewed with the outer domain facing forward. The structure is rendered as a ribbon diagram, with the V3 loop shown in yellow and the rest of gp120 shown in green. The Asn residues bearing the N-linked glycans that constitute the core of the 2G12 epitope on subtype B gp120 are highlighted in blue as space-filling models, while those supposedly involved in limiting glycosidase trimming are shown in red. The Asn at position 442, identified here as potentially important for the formation of the 2G12 epitope on subtype C gp120, is highlighted in orange. Coordinates were taken from the structure of the gp120JRFL core with V3 ligated with CD4 and X5 (Protein Data Bank accession no. 2B4C). The figure was generated with PyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC, South San Francisco, CA [http://www.pymol.org]).

The glycan at position 386 seems to be important for the formation of the 2G12 epitope in subtype C viruses, as it is in subtype B viruses. For both COT9.6 and COT6.15, removal of the glycosylation site at position 386 resulted in resistance to 2G12 neutralization. Unexpectedly, the same mutation showed a marked effect on neutralization by IgG1b12, with a >10-fold increase in sensitivity. The convergence of the 2G12 and b12 epitopes at position 386 was suggested previously based on epitope mapping results (34, 37). This is supported by the recent crystal structure of b12 in complex with a conformationally constrained gp120, in which it is demonstrated that the tip of the CDRH3 domain of b12 interacts with the Asn at position 386 (42). Although Asn386 is not involved in the interaction of CD4 with gp120 (17, 20, 42), we observed a reduction in neutralization sensitivity to CD4-IgG2 when this glycan was deleted, in agreement with previous alanine mutagenesis results (34). Removal of the Asn at position 386 in COT9.6 also resulted in enhanced sensitivity to neutralization by two HIV-positive polyclonal samples. These two plasma samples have broadly neutralizing activity (E. Gray et al., unpublished results), and we are currently exploring whether this is due to the presence of b12-like antibodies, as others have reported (8, 25).

2G12 represents a rare human MAb that shows neutralizing activity against >60% of subtype B HIV-1 isolates in vitro (3, 23). Studies with animals suggest that this antibody is effective at preventing HIV-1 subtype B infection in vivo (1, 27, 28). Recent studies with humans have shown that this MAb can control HIV-1 replication in individuals acutely infected with subtype B viruses (38). However, escape occurs rapidly and is largely confined to glycosylation sites at positions 295, 332, 339, 386, and 392, further supporting the notion that these sites bear glycans that are important for 2G12 binding on subtype B envelopes (26). 2G12-like MAbs are rarely elicited in HIV-infected individuals, probably because the glycans are host derived and thus poorly immunogenic. Nevertheless, the 2G12 epitope is considered a potential vaccine target (33), although its relevance to a subtype C epidemic is doubtful. The absence of the 2G12 epitope in subtype C viruses also hints at possible functional differences between subtype C and B envelope glycoproteins. High-mannose glycans have been implicated in the binding of HIV-1 to DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR (2, 11), and although these are not restricted to the glycans recognized by 2G12, it would be of interest to determine whether or not the interaction of subtype C viruses with dendritic cells and macrophages is affected by the absence of the 2G12 epitope.

The inability of 2G12 to neutralize HIV-1 subtype C strains, which are now responsible for more than half of global infections, stresses the need to further study and characterize subtype C envelope glycoproteins both antigenically and structurally. Defining the basis for 2G12 resistance might allow for a better understanding of the structure of subtype C envelopes and provide insight into whether a 2G12-like epitope exists on these viruses. More importantly, our results suggest that different neutralization epitopes that might constitute possible targets for vaccine design may be present on subtype C envelopes.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Montefiori for providing the cloned Du151.2 envelope plasmid, Beatrice Hahn for the pSG3Δenv HIV-1 construct, and Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for CD4-IgG2 (PRO542). We are also thankful to Dennis Burton and Rogier Sanders for helpful discussions. We thank the Neutralizing Antibody Consortium (NAC) of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) for providing some of the MAb preparations used in this study.

This work was funded by the South African AIDS Vaccine Initiative (SAAVI). Lynn Morris is a Wellcome Trust International Senior Research Fellow.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baba, T. W., V. Liska, R. Hofmann-Lehmann, J. Vlasak, W. Xu, S. Ayehunie, L. A. Cavacini, M. R. Posner, H. Katinger, G. Stiegler, B. J. Bernacky, T. A. Rizvi, R. Schmidt, L. R. Hill, M. E. Keeling, Y. Lu, J. E. Wright, T. C. Chou, and R. M. Ruprecht. 2000. Human neutralizing monoclonal antibodies of the IgG1 subtype protect against mucosal simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection. Nat. Med. 6:200-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baribaud, F., S. Pohlmann, and R. W. Doms. 2001. The role of DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR in HIV and SIV attachment, infection, and transmission. Virology 286:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binley, J. M., T. Wrin, B. Korber, M. B. Zwick, M. Wang, C. Chappey, G. Stiegler, R. Kunert, S. Zolla-Pazner, H. Katinger, C. J. Petropoulos, and D. R. Burton. 2004. Comprehensive cross-clade neutralization analysis of a panel of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 78:13232-13252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bures, R., L. Morris, C. Williamson, G. Ramjee, M. Deers, S. A. Fiscus, S. Abdool-Karim, and D. C. Montefiori. 2002. Regional clustering of shared neutralization determinants on primary isolates of clade C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from South Africa. J. Virol. 76:2233-2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calarese, D. A., C. N. Scanlan, M. B. Zwick, S. Deechongkit, Y. Mimura, R. Kunert, P. Zhu, M. R. Wormald, R. L. Stanfield, K. H. Roux, J. W. Kelly, P. M. Rudd, R. A. Dwek, H. Katinger, D. R. Burton, and I. A. Wilson. 2003. Antibody domain exchange is an immunological solution to carbohydrate cluster recognition. Science 300:2065-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, H., X. Xu, A. Bishop, and I. M. Jones. 2005. Reintroduction of the 2G12 epitope in an HIV-1 clade C gp120. AIDS 19:833-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derdeyn, C. A., J. M. Decker, F. Bibollet-Ruche, J. L. Mokili, M. Muldoon, S. A. Denham, M. L. Heil, F. Kasolo, R. Musonda, B. H. Hahn, G. M. Shaw, B. T. Korber, S. Allen, and E. Hunter. 2004. Envelope-constrained neutralization-sensitive HIV-1 after heterosexual transmission. Science 303:2019-2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhillon, A. K., H. Donners, R. Pantophlet, W. E. Johnson, J. M. Decker, G. M. Shaw, F. H. Lee, D. D. Richman, R. W. Doms, G. Vanham, and D. R. Burton. 2007. Dissecting the neutralizing antibody specificities of broadly neutralizing sera from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected donors. J. Virol. 81:6548-6562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frost, S. D., Y. Liu, S. L. Pond, C. Chappey, T. Wrin, C. J. Petropoulos, S. J. Little, and D. D. Richman. 2005. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope variation and neutralizing antibody responses during transmission of HIV-1 subtype B. J. Virol. 79:6523-6527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaschen, B., J. Taylor, K. Yusim, B. Foley, F. Gao, D. Lang, V. Novitsky, B. Haynes, B. H. Hahn, T. Bhattacharya, and B. Korber. 2002. Diversity considerations in HIV-1 vaccine selection. Science 296:2354-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geijtenbeek, T. B., D. S. Kwon, R. Torensma, S. J. van Vliet, G. C. van Duijnhoven, J. Middel, I. L. Cornelissen, H. S. Nottet, V. N. KewalRamani, D. R. Littman, C. G. Figdor, and Y. van Kooyk. 2000. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell 100:587-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert, P. B., V. Novitsky, and M. Essex. 2005. Covariability of selected amino acid positions for HIV type 1 subtypes C and B. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 21:1016-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gnanakaran, S., D. Lang, M. Daniels, T. Bhattacharya, C. A. Derdeyn, and B. Korber. 2007. Clade-specific differences between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clades B and C: diversity and correlations in C3-V4 regions of gp120. J. Virol. 81:4886-4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray, E. S., T. Meyers, G. Gray, D. C. Montefiori, and L. Morris. 2006. Insensitivity of paediatric HIV-1 subtype C viruses to broadly neutralising monoclonal antibodies raised against subtype B. PLoS Med. 3:e255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray, E. S., P. L. Moore, I. A. Choge, J. M. Decker, F. Bibollet-Ruche, H. Li, N. Leseka, F. Treurnicht, K. Mlisana, G. M. Shaw, S. S. Karim, C. Williamson, and L. Morris. 2007. Neutralizing antibody responses in acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C infection. J. Virol. 81:6187-6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrera, C., P. J. Klasse, E. Michael, S. Kake, K. Barnes, C. W. Kibler, L. Campbell-Gardener, Z. Si, J. Sodroski, J. P. Moore, and S. Beddows. 2005. The impact of envelope glycoprotein cleavage on the antigenicity, infectivity, and neutralization sensitivity of Env-pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. Virology 338:154-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, C. C., M. Tang, M. Y. Zhang, S. Majeed, E. Montabana, R. L. Stanfield, D. S. Dimitrov, B. Korber, J. Sodroski, I. A. Wilson, R. Wyatt, and P. D. Kwong. 2005. Structure of a V3-containing HIV-1 gp120 core. Science 310:1025-1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson, V. A., and R. E. Byington. 1990. Quantitative assays for virus infectivity, p. 71-76. In A. Aldovini and B. D. Walker (ed.), Techniques in HIV research. Stockton Press, New York, NY.

- 19.Koch, M., M. Pancera, P. D. Kwong, P. Kolchinsky, C. Grundner, L. Wang, W. A. Hendrickson, J. Sodroski, and R. Wyatt. 2003. Structure-based, targeted deglycosylation of HIV-1 gp120 and effects on neutralization sensitivity and antibody recognition. Virology 313:387-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwong, P. D., R. Wyatt, J. Robinson, R. W. Sweet, J. Sodroski, and W. A. Hendrickson. 1998. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature 393:648-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leonard, C. K., M. W. Spellman, L. Riddle, R. J. Harris, J. N. Thomas, and T. J. Gregory. 1990. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 265:10373-10382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, B., J. M. Decker, R. W. Johnson, F. Bibollet-Ruche, X. Wei, J. Mulenga, S. Allen, E. Hunter, B. H. Hahn, G. M. Shaw, J. L. Blackwell, and C. A. Derdeyn. 2006. Evidence for potent autologous neutralizing antibody titers and compact envelopes in early infection with subtype C human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 80:5211-5218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, M., F. Gao, J. R. Mascola, L. Stamatatos, V. R. Polonis, M. Koutsoukos, G. Voss, P. Goepfert, P. Gilbert, K. M. Greene, M. Bilska, D. L. Kothe, J. F. Salazar-Gonzalez, X. Wei, J. M. Decker, B. H. Hahn, and D. C. Montefiori. 2005. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env clones from acute and early subtype B infections for standardized assessments of vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 79:10108-10125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, M., J. F. Salazar-Gonzalez, C. A. Derdeyn, L. Morris, C. Williamson, J. E. Robinson, J. M. Decker, Y. Li, M. G. Salazar, V. R. Polonis, K. Mlisana, S. A. Karim, K. Hong, K. M. Greene, M. Bilska, J. Zhou, S. Allen, E. Chomba, J. Mulenga, C. Vwalika, F. Gao, M. Zhang, B. T. Korber, E. Hunter, B. H. Hahn, and D. C. Montefiori. 2006. Genetic and neutralization properties of subtype C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 molecular env clones from acute and early heterosexually acquired infections in southern Africa. J. Virol. 80:11776-11790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, Y., S. A. Migueles, B. Welcher, K. Svehla, A. Phogat, M. K. Louder, X. Wu, G. M. Shaw, M. Connors, R. T. Wyatt, and J. R. Mascola. Broad HIV-1 neutralization mediated by CD4 binding site antibodies. Nat. Med., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Manrique, A., P. Rusert, B. Joos, M. Fischer, H. Kuster, C. Leemann, B. Niederost, R. Weber, G. Stiegler, H. Katinger, H. F. Gunthard, and A. Trkola. 2007. In vivo and in vitro escape from neutralizing antibodies 2G12, 2F5, and 4E10. J. Virol. 81:8793-8808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mascola, J. R. 2002. Passive transfer studies to elucidate the role of antibody-mediated protection against HIV-1. Vaccine 20:1922-1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mascola, J. R., M. G. Lewis, G. Stiegler, D. Harris, T. C. VanCott, D. Hayes, M. K. Louder, C. R. Brown, C. V. Sapan, S. S. Frankel, Y. Lu, M. L. Robb, H. Katinger, and D. L. Birx. 1999. Protection of macaques against pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus 89.6PD by passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 73:4009-4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCaffrey, R. A., C. Saunders, M. Hensel, and L. Stamatatos. 2004. N-linked glycosylation of the V3 loop and the immunologically silent face of gp120 protects human immunodeficiency virus type 1 SF162 from neutralization by anti-gp120 and anti-gp41 antibodies. J. Virol. 78:3279-3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montefiori, D. C. 2004. Evaluating neutralizing antibodies against HIV, SIV and SHIV in luciferase reporter gene assays, p. 12.11.1-12.11.15. In J. E. Coligan, A. M. Kruisbeek, D. H. Margulies, E. M. Shevach, W. Strober, and R. Coico (ed.), Current protocols in immunology. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Moore, J. P., and J. Sodroski. 1996. Antibody cross-competition analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 exterior envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 70:1863-1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakowitsch, S., H. Quendler, H. Fekete, R. Kunert, H. Katinger, and G. Stiegler. 2005. HIV-1 mutants escaping neutralization by the human antibodies 2F5, 2G12, and 4E10: in vitro experiments versus clinical studies. AIDS 19:1957-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pantophlet, R., and D. R. Burton. 2006. gp120: target for neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 24:739-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pantophlet, R., E. Ollmann Saphire, P. Poignard, P. W. Parren, I. A. Wilson, and D. R. Burton. 2003. Fine mapping of the interaction of neutralizing and nonneutralizing monoclonal antibodies with the CD4 binding site of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120. J. Virol. 77:642-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poignard, P., R. Sabbe, G. R. Picchio, M. Wang, R. J. Gulizia, H. Katinger, P. W. Parren, D. E. Mosier, and D. R. Burton. 1999. Neutralizing antibodies have limited effects on the control of established HIV-1 infection in vivo. Immunity 10:431-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanders, R. W., M. Venturi, L. Schiffner, R. Kalyanaraman, H. Katinger, K. O. Lloyd, P. D. Kwong, and J. P. Moore. 2002. The mannose-dependent epitope for neutralizing antibody 2G12 on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp120. J. Virol. 76:7293-7305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scanlan, C. N., R. Pantophlet, M. R. Wormald, E. Ollmann Saphire, R. Stanfield, I. A. Wilson, H. Katinger, R. A. Dwek, P. M. Rudd, and D. R. Burton. 2002. The broadly neutralizing anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2G12 recognizes a cluster of alpha1→2 mannose residues on the outer face of gp120. J. Virol. 76:7306-7321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trkola, A., H. Kuster, P. Rusert, B. Joos, M. Fischer, C. Leemann, A. Manrique, M. Huber, M. Rehr, A. Oxenius, R. Weber, G. Stiegler, B. Vcelar, H. Katinger, L. Aceto, and H. F. Gunthard. 2005. Delay of HIV-1 rebound after cessation of antiretroviral therapy through passive transfer of human neutralizing antibodies. Nat. Med. 11:615-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trkola, A., M. Purtscher, T. Muster, C. Ballaun, A. Buchacher, N. Sullivan, K. Srinivasan, J. Sodroski, J. P. Moore, and H. Katinger. 1996. Human monoclonal antibody 2G12 defines a distinctive neutralization epitope on the gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 70:1100-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei, X., J. M. Decker, S. Wang, H. Hui, J. C. Kappes, X. Wu, J. F. Salazar-Gonzalez, M. G. Salazar, J. M. Kilby, M. S. Saag, N. L. Komarova, M. A. Nowak, B. H. Hahn, P. D. Kwong, and G. M. Shaw. 2003. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature 422:307-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu, X., A. B. Parast, B. A. Richardson, R. Nduati, G. John-Stewart, D. Mbori-Ngacha, S. M. Rainwater, and J. Overbaugh. 2006. Neutralization escape variants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are transmitted from mother to infant. J. Virol. 80:835-844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou, T., L. Xu, B. Dey, A. J. Hessell, D. Van Ryk, S. H. Xiang, X. Yang, M. Y. Zhang, M. B. Zwick, J. Arthos, D. R. Burton, D. S. Dimitrov, J. Sodroski, R. Wyatt, G. J. Nabel, and P. D. Kwong. 2007. Structural definition of a conserved neutralization epitope on HIV-1 gp120. Nature 445:732-737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu, X., C. Borchers, R. J. Bienstock, and K. B. Tomer. 2000. Mass spectrometric characterization of the glycosylation pattern of HIV-gp120 expressed in CHO cells. Biochemistry 39:11194-11204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]