1. Introduction

The midgut of larval dipteran insects consists of a simple tube lined with a single layer of epithelial cells. Based on epithelial cell morphology and topography, three distinct regions- the anterior midgut, posterior midgut, and an intermediate transition zone- have been described (Clark et al., 2005). The muscularis is composed of bands of longitudinal and circular muscle (Park et al., 2000, Goldstein et al., 1971; Copenhaver et al., 1996) which form a mesh-like grid. This contrasts with the visceral smooth muscle characteristic of vertebrates, where both circular and longitudinal muscle is found in discrete sheets or layers separated by the nerves of the enteric plexus.

While smooth muscle is found associated with the viscera in vertebral systems, all insect muscle is striated. Insect visceral muscle differs from flight muscle not in relation to the presence or absence of sarcomeres, but in other cytological features. For example, insect visceral muscle tends to have a much greater number of actin filaments per individual myosin filament than found in flight muscle (Smith et al., 1966; Nagai et al., 1974). The sarcoplasmic reticulum is often reduced or absent in many insect visceral muscle fibers, making them less able to sequester cytoplasmic Ca2+ relative to flight muscle (Schaeffer et al., 1967; Goldstein et al., 1974; Klowden, 2002).

The midgut of the larval mosquito is one of the animal’s interfaces with the external environment and is involved in ionic homeostasis and osmoregulation as well as digestion. The present studies of the structure and ultrastructure of the muscularis of this organ in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th larval instars were prompted by our interest in understanding the mechanisms by which the multiple functions of the midgut are controlled and integrated by neurotransmitters and hormones. Previously, we had found that both alkali secretion and motility of the isolated, perfused anterior stomach were stimulated by serotonin (Clark et al., 2000; Onken et al., 2004; Onken et al., 2004a), and that the midgut receives an extensive serotonergic innervation that is derived from a small number of bilateral neurons (Moffett & Moffett, 2005). Several Aedes neuropeptides were found to have inhibitory effects on motility, ion transport, or both functions (Onken et al. 2004a), and these effects may be reflected by an apparent peptidergic innervation of the gut and by the presence of a substantial population of enteroendocrine cells (Moffett & Moffett, 2005).

It has been recognized for some time that some insect muscle fibers, including a number of examples from dipteran insects (Rice, 1970; Jones & Zeve, 1968; Osborne, 1967; Jones, 1960), display perforated Z-disks that permit the possibility of supercontraction, a state in which thick filaments from one sarcomere may project into the next adjacent sarcomeres on each side. Examples of this are found in the present studies.

2. Methods

2.1 Mosquitoes

Aedes aegypti eggs (Vero Beach strain) were obtained from a colony continuously maintained by Dr. Marc Klowden, University of Idaho (Moscow, ID). Larvae were hatched into a 1:1 mixture of local tap water and deionized water containing a small amount of yeast. The water mixture was replaced daily. The larvae were reared at 26°C with a photoperiod of 18L: 6D and fed ground Tetramin flakes (Tetrawerke, Melle, Germany) daily. Animals were fixed and prepared for electron microscope examination (TEM and SEM) at the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th larval instars. Only 4th instar larvae were prepared for the confocal microscope. Larvae nearing ecdysis, as indicated by increasing paleness, were not used.

2.2 Transmission Electron Microscopy

Freshly dissected tissues were fixed overnight in cold 2-2.5% glutaraldehyde/2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2). Following aldehyde fixation, tissues received the following treatments:

Rinses, 0.1 M cacodylate buffer.

Incubation in 2% OsO4 in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (2 hours).

Rinses, distilled water.

Incubation in 1% tannic acid (1 hour).

Rinses, distilled water.

Incubation in 2% uranyl acetate (2 hours).

Rinse, distilled water.

Dehydration, graded ethanol series followed by acetone.

Infiltration of SPURRS resin, involving liquid resin and acetone (1:1 ratio, overnight).

Infiltration, SPURRS resin without acetone (3-5 hours).

Embedding in SPURRS, overnight, at 70°.

Ultrathin sections (~50-75 nm; silver to gold color) were cut with glass or diamond knives on a Reichert Ultracut R microtome (Cambridge Instruments, W. Germany), placed on formvar coated grids, and stained with 4% uranyl acetate followed by Reynolds’ Lead. Specimens were viewed on a JOEL JEM 1200 EX TEM (JOEL USA, Inc., Peabody, MA, acceleration beam approx. 70 uA). Images were captured via digital camera and processed with analySIS software version 3.2 (Soft Imaging System).

2.3 Scanning Electron Microscopy

Tissues were fixed overnight in cold 2-2.5% glutaraldehyde/2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2). Following aldehyde fixation, tissues received the following treatment:

Rinses, 0.1 M cacodylate buffer.

Incubation in 2% OsO4 in 0.1 M cacodylate (2 hours).

Rinses, 0.1 M cacodylate buffer

Dehydration, graded ethanol series, acetone, and hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS).

After the specimens were dehydrated, the HMDS was permitted to vent for at least 12 hours. Specimens were subsequently gold-coated on a Technics Hummer V sputter coater (Technics, San Jose, CA). Samples were examined using a Hitachi S 570 SEM (Hitachi LTD, Tokyo, Japan, acceleration beam 20-25 kV). Images were captured and stored digitally with Quartz PCI v. 4.2- Scientific Image Management System (Quartz Imaging Corporation).

2.4 Confocal Microscopy

Isolated midguts from fourth instar larvae were dissected, placed in ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4, containing 137 mM NaCl + 50 mM Na2HPO4), and prepared for viewing on the confocal microscope using phalloidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), an actin specific stain, conjugated to Alexa-Flor 488 via the following protocol:

Isolated midguts transferred to fresh PBS for 10 minute incubation

20 minute quick fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde in 150 mM TBST (0.3% Tween 20; pH 7.2) room temperature

Rinses, PBS

Rinse, 150 mM TBST + 1% Bovine Serum Albumen (BSA)

Incubation in 0.165 mM phalloidin in 150 mM TBST + 1% BSA, 1.5 hours, room temperature

Rinses, PBS

Following fixation and staining, specimens were mounted between two glass slides using Vecta-Shield mounting medium for fluorescence, with propidium iodide (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) and refrigerated overnight. Samples were viewed on a BioRad MRC 1024 confocal microscope (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Philadelphia, PA). Images were captured using LaserSharp 2000 software for the MRC 1024 microscope (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Philadelphia, PA).

2.5 Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed, when appropriate, with ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc exams. ANOVA exams were run using SAS Analysis Package, PROC GLM (Statistical Analysis Software Institute, INC.).

3. Results

3.1 Gross morphology of the larval midgut muscularis

The muscularis of the larval Aedes aegypti midgut is organized as a grid-like network of several longitudinally and circularly orientated bands, comprised of one or more muscle fibers (Fig. 1, 2a-b, Fig. 3a-d, Fig. 11a-c). The directionality and orientation of these bands is not uniform throughout the entirety of the larval midgut. Some muscle bands contain fibers that project along a discrete, single axis (Fig. 2a). In many cases both circular and longitudinal bands clearly overlap at regions of intersection, with the longitudinal bands running external (farther from the midgut epithelium) relative to the circular ones. However, in the anterior midgut, intersections between longitudinal and circular bands generally included some fibers, dubbed “cruciform cells”, that had both longitudinal and circular processes (Fig. 2b, Fig. 11a).

FIGURE 1.

Images of whole guts from the 2nd (A), 3rd (B) and 4th (C) instars of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. In each image, the anterior midgut is located in the upper right and the posterior midgut in the lower left. Each image was recorded at the same magnification (50x). Scale bars, located on the lower right margin of each image, represent 600 microns.

FIGURE 2.

A: SEM micrograph of a 4th instar Aedes aegypti anterior midgut, magnification 700X. Regions of longitudinal muscle bands (L) overlapping circular bands (C) are present.Bifurcating circular bands of muscle (BC) are also present. Scale bar (lower right margin) represents 43 μm.

B: SEM micrograph of a 2nd instar Aedes aegypti anterior midgut, magnification 500X. Cruciform regions of muscularis (A), containing both circular and longitudinal filaments within a single plane, are present in some specimens. Ovoid swellings (O) can be observed on both circular (C) and longitudinal (L) muscle bands. Gastric cecae (GC) are located along the upper border of the image. Scale bar (lower right margin) represents 60 μm.

FIGURE 3.

A & B: SEM micrographs of branching circular muscle (BC) in the anterior (A) and posterior (B) midgut of a 3rd instar Aedes aegypti larva. Magnification in both micrographs is 400X. C= circular muscle; L= longitudinal muscle; GC= gastric cecae. Scale bars (lower right margin) represent 75 μm.

C & D: SEM micrographs illustrating branching longitudinal muscle (BL) in the posterior midgut of a 4th instar Aedes aegypti larva. C= circular muscle; L= longitudinal muscle; MT= Malpighian tubule; HG= hindgut; PMG= posterior midgut. Scale bars (lower right margins) represent 86 μm (C) and 38 μm (D).

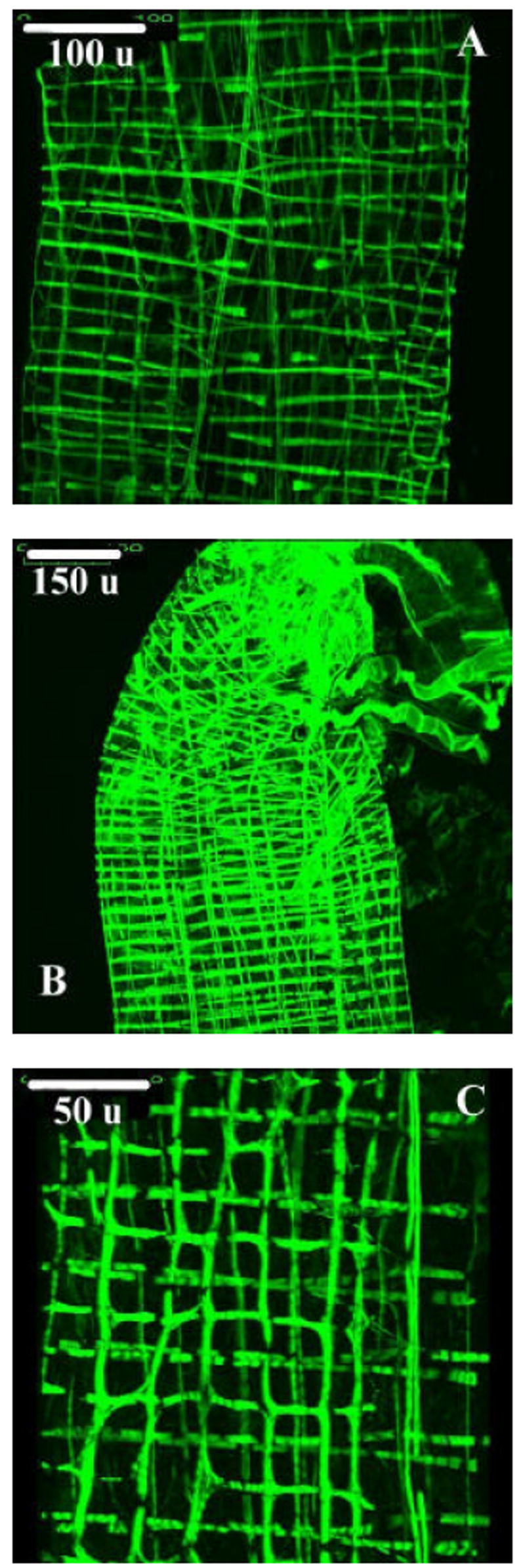

FIGURE 11.

A: Three dimentional projection image from the anterior midgut of a 4th instar Aedes aegypti larva prepared for the confocal microscope using phalloidin conjugated to Alexa-Fluor 488. Bifurcations of circular muscle bands, as well as cruciform regions, can be identified. Scale bar (upper left corner) represents 100 microns.

B: Three dimensional projection image from the posterior midgut of a 4th instar Aedes aegypti larva prepared for the confocal microscope using phalloidin. Bifurcating circular and longitudinal muscle bands can be identified. Scale bar (upper left corner) represents 150microns.

C: Three dimensional projection image from the anterior midgut of a 4th instar Aedes aegypti larva prepared for the confocal microscope using phalloidin. Sharing of filaments between otherwise distinct bands of muscle can be observed. Longitudinal muscle bands are in the vertical orientation. Scale bar (upper left corner) represents 50 microns.

A suspending membrane is associated with many bands of longitudinal muscle (Fig. 6a & b). In some cases, two or more bands of longitudinal muscle share a common suspending element. The longitudinal bands tend to lie much closer to the basal lamina in the posterior midgut (Fig. 6a) than those associated with the anterior midgut (Fig. 6b). The circular bands of muscle lie close to the basal lamina in both the anterior and posterior midgut (Fig. 8a-c).

FIGURE 6.

A: Cross section through a longitudinal muscle from the posterior midgut of a 2nd instar Aedes aegypti larva. Scale bar represents 1 μm.

B: Cross section through a longitudinal muscle from the anterior midgut of a 3rd instar Aedes aegypti larva. Scale bar represents 1 μm.

LM= Longitudinal muscle; SM= Suspending membrane; T= Tracheolar cell; ME= Midgut epithelium; BM= Basement membrane.

FIGURE 8.

A: Longitudinal section, circular muscle from the anterior midgut of a 2nd instar Aedes aegypti larva. Scale bar represents 1 μm.

B: Longitudinal section, circular muscle from the anterior midgut of a 3rd instar Aedes aegypti larva. Scale bar represents 2 μm.

C: Longitudinal section, circular muscle from the anterior midgut of a 4th instar Aedes aegypti larva. Scale bar represents 5 μm.

D: Longitudinal section, circular muscle from the anterior midgut of a 3rd instar Aedes aegypti larva. Scale bar represents 1 μm.

CM= Circular muscle; LM= Longitudinal muscle; S= Sarcoplasm; Z= Z-lines; I= I bands; M= Mitochondria; T= Tracheolar cell; ME= Midgut epithelium.

Large, ovoid swellings are present in many bands of muscle, both longitudinal and circular (Fig. 2b). These swellings range in diameter from 3-5 μm and correlate, in size, with images of muscle fiber nuclei observed in the TEM. Some circular muscle bands possess two or more of these ovoid swellings, particularly in conjunction with the wishbone branching pattern of bifurcation and merging of circular muscle bands (Fig. 2b). Many swellings in longitudinal bands of muscle appear more oblong than those associated with circular muscle (Fig. 2b).

Small breaks in actin content are present in some bands of circular muscle (Fig. 11a, 11c). These gaps appear not to be associated with Z discs (responsible for anchoring actin filaments). As myosin specific staining was not conducted, it is presently unknown if this contractile protein is present or absent in such actin lacking regions.

Several bands of circular muscle, which do not wholly encircle the midgut, are present in the anterior midgut (Fig. 5). These incomplete bands can be observed as early as the second larval instar. Incomplete circular bands have not been observed in the posterior region of the midgut. The mean length of the incomplete bands does not statistically increase during the larval stadia (p=0.0534, ANOVA; Table 1). The mean distance between these incomplete bands likewise does not significantly increase (p=0.1076, ANOVA; Table 1). The width of these incomplete bands significantly increases between the 2nd and 3rd larval instars (Table 1).

FIGURE 5.

Incomplete bands of circular muscle (IC) associated with the anterior midgut of a 4th instar Aedes aegypti larva. L= longitudinal muscle, C= circular muscle. Scale bar (lower right margin) represents 50 μm.

Table 1.

Incomplete Circular Bands

| Band Length, μm | Band Spacing, μm | Band Width, μm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd Instar | 31.5±3.8 | 14.7±2.2 | 1.8±0.1 |

| 3rd Instar | 46.3±3.4 | 21.7±0.8 | 2.3±0.2 |

| 4th Instar | 49.8±3.9 | 21.4±0.5 | 2.4±0.1 |

| Significant Differences* | No groups different | No groups different | 2nd&3rd, 2nd&4th instars |

Values represent means ± standard error, in microns.

All statistically significant differences are at p<0.01, Tukey’s Test, unless otherwise indicated.

Bifurcation of some longitudinal muscle bands can be observed along the medial aspect of the very posterior end of the midgut, quite close to the junction with the hindgut (Fig. 3c-d). Branching of circular muscle bands is frequent in both anterior and posterior portions of the midgut (Fig. 3a-b). Branches of adjacent circular muscle fibers merge, in a wishbone like manner, resulting in the interconnection of bands across much of the length of the midgut. These branching circular muscle bands are observed as early as the second larval instar. Branching of longitudinal muscle bands occurs by the third larval instar. Some bands of longitudinal muscle can be observed extending beyond the boundaries of the midgut, continuing on to the foregut (Fig. 4a) and hindgut (Fig. 4b). Bands of muscle may be associated with tracheolar cells (Fig. 6a).

FIGURE 4.

A: Longitudinal muscle (LM) extending onto the foregut (FG) of a 3rd instar Aedes aegypti larva. GC= gastric ceca; AMG= anterior midgut. Scale bar (lower right margin) represents 60 μm.

B: Longitudinal muscle (L) extending onto the hindgut (HG) of a 3rd instar Aedes aegypti larva. MT= Malpighian tubules; PMG= posterior midgut; BL= branching longitudinal muscle. Scale bar (lower right margin) represents 75 μm.

Some muscle bands share contractile elements (Fig. 11c). Myofibrils are shared between both circular and longitudinal bands of muscle, which appear to be otherwise discrete. Myofibril sharing occurs in both the anterior and posterior midgut. While it can occur in conjunction with the cruciform cells (described in Section 3.2), myofibril sharing is not restricted to the regions of the anterior midgut in which the cruciform cells are found.

The number of circular muscle bands per 100 um present in the anterior midgut significantly decreases between the 2nd and 3rd larval instars (Table 2). There is no significant difference in the mean number of circular muscle bands per 100 μm observed in the anterior midgut of 3rd and 4th larval instar larvae. This decrease in the mean number of circular bands is seen in conjunction with a significant increase in the distance between them (Table 2). A similar trend is seen in the longitudinal bands of muscle associated with the anterior midgut; the mean number of bands decreases between the 2nd and 3rd instars, while the distance between them significantly increases. There is no significant difference in either the number of longitudinal muscle bands or distance between them in the anterior midgut of 3rd and 4th instar larvae (Table 3).

Table 2.

Circular Muscle Bands, Anterior Midgut

| # per 100 μm | Band Spacing, μm | Band Width, μm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd Instar | 13.9±1.9 | 8.2±0.6 | 1.5±0.1 |

| 3rd Instar | 7.1±0.4 | 16.8±0.8 | 2.8±0.1 |

| 4th Instar | 4.4±0.3 | 21.9±1.3 | 2.5±0.3 |

| Significant Differences* | 2nd&3rd, 2nd&4th instars | All groups different | 2nd & 3rd instars |

Values represent means ± standard error, in microns.

All statistically significant differences are at p<0.01, Tukey’s Test, unless otherwise indicated.

Table 3.

Longitudinal Muscle Bands, Anterior Midgut

| # per 100 μm | Band Spacing, μm | Band Width, μm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd Instar | 14.8±1.6 | 6.7±0.3 | 1.1±0.1 |

| 3rd Instar | 8.8±0.6 | 13.2±0.1 | 1.3±0.3 |

| 4th Instar | 8.4±0.4 | 14.5±0.9 | 1.7±0.2 |

| Significant Differences* | 2nd & 3rd instars | 2nd & 3rd instars | 2nd & 4th, 3rd & 4th instars |

Values represent means ± standard error, in microns.

All statistically significant differences are at p<0.01, Tukey’s Test, unless otherwise indicated.

In the posterior midgut, while the distance between the circular bands increases significantly between the 2nd and 4th instars, the mean number of circular bands in the posterior midgut does not significantly change (Table 4). The longitudinal muscle bands become farther apart as the animal transitions from the 2nd to 3rd instar. The distance between the bands then significantly decreases by the 4th instar (Table 5). The mean number of longitudinal muscle bands per 100 μm does not significantly change throughout the larval stadia (p=0.6762, ANOVA).

Table 4.

Circular Muscle Bands, Posterior Midgut

| # per 100 μm | Band Spacing, μm | Band Width, μm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd Instar | 9.5±1.9 | 12.5±0.8 | 1.7±0.1 |

| 3rd Instar | 7.5±1.4 | 15.7±0.9 | 2.7 ±0.2 |

| 4th Instar | 5.1±0.4 | 25.2±0.7 | 4.6±0.4 |

| Significant Differences* | No differences | All groups different | All groups different |

Values represent means ± standard error, in microns.

All statistically significant differences are at p<0.01, Tukey’s Test, unless otherwise indicated.

Table 5.

Longitudinal Muscle Bands, Posterior Midgut

| # per 100 μm | Band Spacing, μm | Band Width, μm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd Instar | 4.9(5)±1.4 | 14.4±0.9 | 1.8±0.2 |

| 3rd Instar | 3.9(9)±0.5 | 30.5±0.6 | 3.2±0.1 |

| 4th Instar | 5.2±0.3 | 25.4±1.3 | 4.0±0.8 |

| Significant Differences* | No groups different | All groups different | All groups different |

Values represent means ± standard error, in microns.

All statistically significant differences are at p<0.01, Tukey’s Test, unless otherwise indicated.

As seen in Tables 2-5, the width of both circular and longitudinal muscle bands increases as animals mature through the larval stadia. The mean width of the circular muscle bands in the anterior midgut increases between the 2nd and 3rd instars (Table 2). Circular band spacing and width increase in both the anterior and posterior midgut at all instars (Table 2; Table 4). The mean width of the longitudinal bands of muscle associated with the anterior midgut increases (Table 3). In the posterior midgut, the longitudinal muscle bands show a significant increase in width across all larval instars (Table 5).

3.2 Fine structure of the larval midgut muscularis

Thick and thin filaments are already present in muscle fibers by the second larval instar. Filaments are sparse in some fibers at this early stage (Fig. 7a), and the remaining cytoplasm tends to be highly granular and contains both light- to medium staining vacuoles and mitochondria. In some circular fibers, the portion of the cell not occupied by contractile machinery constitutes a significant portion of the total fiber volume, even in the fourth instar (Fig. 8b-c). Fibers develop more filaments as they progress through the larval stadia and become much more densely filled by the fourth larval instar (Fig. 7b-c). In the anterior midgut, actin filaments stain much more faintly and, as a result, appear much less distinct than those in the posterior midgut. The thicker myosin filaments stain heavily in both regions of the midgut (Fig. 7c, Fig 9a, Fig. 10b).

FIGURE 7.

A: Cross section, longitudinal muscle from the anterior midgut of a 2nd instar Aedes aegypti larva. Scale bar represents 1 μm.

B: Cross section, longitudinal muscle from the posterior midgut of a 3rd instar Aedes aegypti larva. Scale bar represents 0.5 μm.

C: Cross section, longitudinal muscle from the posterior midgut of a 4th instar Aedes aegypti larva. Scale bar represents 0.5 μm.

L= Longitudinal muscle; AMF= Actin & myosin filaments; SM= Sarcoplasmic membrane; MI= Membrane invagination; BM= Basement membrane; ME= Midgut epithelium; M= Mitochondria.

FIGURE 9.

A: Cross section through a cruciform cell from the anterior midgut of a 2nd instar Aedes aegypti larva. Scale bar represents 0.5 μm.

B: Cross section through a cruciform cell from the anterior midgut of a 3rd instar Aedes aegypti larva. Scale bar represents 1 μm.

C: Cross section through a cruciform cell from the anterior midgut of a 4th instar Aedes aegypti larva. Scale bar represents 1 μm.

D: Cross section through a cruciform cell from the anterior midgut of a 4th instar Aedes aegypti larva, representing the lower portion of the muscle in Figure 9C at a higher magnification. Scale bar represents 0.5 μm.

BM= Basement membrane; ME= Membrane epithelium; LF: Longitudinally oriented filaments; CF= Circularly oriented filaments; S= Sarcoplasm; M= Mitochondria.

FIGURE 10.

A & B: Cross section through longitudinal muscle from the posterior midgut of a third instar Aedes aegypti larva. Membrane invaginations (MI) of the sarcoplasmic membrane (SM) are present. Actin and myosin filaments (AMF) are distinct. Mitochondria (M) are present in some muscle fibers. The basement membrane (BM) separates the muscle fibers from the midgut epithelium (ME). Scale bars represent 0.2 microns.

The actin-anchoring Z-disks are prominent in circular muscle bands of the anterior midgut as early as the second larval instar (Fig. 8a). In some specimens, the Z-lines are distinctly perforated, with myosin filaments projecting through the gaps into the adjacent sarcomere (Fig. 8a, 8d). I bands are short in the second and third larval instars, and virtually non-existent by the fourth larval instar (Fig 8a-c). These light bands are not observed in the circular muscle associated with the posterior midgut. H zones, containing only myosin filaments, are not clearly observed in any bands of circular muscle, regardless of location. A zones (regions of actin and myosin overlap) are visible in longitudinal muscle in cross-section but are less distinct in circular muscle bands as sectioned, presumably as this region occupies much of the sarcomere’s length.

Cruciform cells of the anterior midgut possess myofibrils running at right angles to one another (Fig. 9a-d). There are typically two or three myofibrils per cell, with longitudinally oriented myofibrils located in the portion of the fiber closest to the basal lamina while circularly oriented ones are located more externally. In cruciform fibers containing more than two regions myofibrils, those of circular orientation are enclosed by longitudinal filaments on both ‘sides’ (Fig. 9b).

Small invaginations of the sarcoplasmic membrane, reminiscent of t-tubules, are occasionally visible in longitudinal fibers (Fig. 7c, 9a, 9d, 10a-b). Invaginations open to the space between the sarcolemma and basement membrane associated with the muscle fibers. These invaginations range in length from 0.2-1.0 μm and are present in multiple larval instars. They can be found on both the haemolymph side (Figure 7c, 10b) and midgut side (Figure 10a) of muscle fibers. Sarcoplasmic reticulum cisternae have not been observed in association with these invaginations. The longitudinal bands of muscle themselves range in width from approximately two to six microns (multiple larval instars) in both the anterior and posterior midgut.

4. Discussion

Very little is known about the structure and development of midgut visceral muscle in larval Aedes aegypti. O’Brien’s 1965 discussion of the midgut muscularis in larval and pupal Ae. aegypti remains one of the few published works in this area. Through the use of the Feulgen reaction and Orange G stain, O’Brien was able to detect what were identified as bands of visceral muscle as early as the first instar- something which, at the time, had been previously unreported. The growth of midgut muscularis was described as continuing throughout the remaining larval instars. The resulting network, illustrated as an octagonal mesh of multinucleated muscle bands lying within a single plane, was said to persist through metamorphosis.

Jones et al. (1968) focused on the gastric ceca of 4th instar larvae. While the main thrust of their research focused on a microscopic examination of the cecal epithelium, the muscularis associated with the eight cecal pouches is briefly examined at the TEM level. Distinct circular and longitudinal fibers were identified, with the circular fibers running externally to those of longitudinal orientation. No fibers containing filaments of differing orientation lying within the same plane were identified, and the gross morphology of the muscularis was not investigated. While extensive in its study of the gastric ceca, the epithelium and muscularis in the remainder of the larval midgut was ignored.

Seron et al. (2004), in their investigation of carbonic anhydrase (CA) expression in the larval Aedes aegypti midgut, identified two classes of muscle bands in this species. Carbonic anhydrase positive muscle bands expressed CA immunoreactivity along the membrane closest to the midgut epithelium, while carbonic anhydrase negative muscle bands displayed no such immunoreactivity. The CA positive bands largely lie along the lateral sides of the anterior midgut.

Our own research indicates several features differing from those described in previous works. O’Brien’s work focused on the gross morphology of the midgut muscularis at the light microscope level, without the inclusion of electron microscopy. Our research involving electron microscopy reveals certain features in contrast with the muscle morphology previously described, as well as several features previously unreported. Additionally, many of the nuclei O’Brien attributed to muscle fibers are now known to lie at a plane other than that of the muscle bands themselves (S. Moffett, personal communication). Jones et al. (1968) included a discussion the structure of cecal muscularis at the TEM level. Many features of the muscularis in the gastric ceca, however, do not apply to the remainder of the larval Aedes aegypti midgut, which was not investigated in this previous study.

Our current understanding of the structure of the larval midgut muscularis allows for both functional and developmental implications.

4.1 Functional Implications

As described by Jones (1960), the anterior stomach of live anophelene larvae shows an activity cycle in which frequent, small adoral peristaltic waves alternate with isolated, larger aboral waves. These movements were not abolished by ganglionic cauterization or ligation, leading Jones to conclude that they are myogenic. The aboral movements may assist the movement of the food string, and the adoral ones the countercurrent flow of fluid from the distal gut to the ceca within the ectoperitrophic space (Ramsay, 1950; cf also Clements 1992, Fig. 6,7). Since the midgut is widely and indiscriminately innervated by a small number of serotonergic neurons, it seems likely that these neurons do not generate any patterned contractile activity. This conclusion is supported also by our observation that multiple modes of rhythmic contractile activity occur in the isolated gut upon exposure to serotonin (Onken et al, 2004). A review of the videotape evidence collected by Onken et al. (2004) showed these modes include both segmentation and adoral peristalsis. Most commonly, regular adoral peristaltic waves are initiated at the junction between anterior and posterior midgut while asynchronous and less frequent segmentation contractions dominate the activity pattern of the posterior midgut (H. Onken, pers.com.). A more complex report of gut movement is apparently characteristic of the gut in vivo (Jones, 1960), suggesting that modulating inputs are important. The gastric ceca contain several cell types, including ion transporting and resorbing/secreting cells, which play a key role in water and ion transport (Clements, 1992). In vivo, the adoral movements of the anterior midgut muscularis most likely serve to propel ectoperitrophic fluid towards the ceca.

Since we did not find evidence of gap junctions between muscle fibers, it remains to be discovered how the contractile rhythms of the two midgut regions originate and may be transmitted to individual muscle fibers. Intrinsic neurons are present within the muscularis (Moffett & Moffett, 2005) and it is possible that they both initiate and coordinate the autonomous activity of the muscularis.

A major conclusion of the present study is that the structure of the muscularis obviates the possibility of separately controlled longitudinal and circular muscle contraction. As many of the circular bands of muscle are connected, in the wishbone like manner illustrated in Figures 3a and 3b, it is conceivable that the activity initiating muscle contraction easily spreads from one band to the next resulting in the observed peristaltic movement. In fact, it may be difficult to avoid such a spread of contractile ‘momentum’ in this manner due to the direct physical connection of the circular bands.

The sharing of contractile elements between otherwise discrete bands of muscle, as indicated in Figure 11C, is also seen in the stomach muscularis of adult female Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes (Park et al., 2000). The proportion of such shared myofibrils in Aedes aegypti larvae is quite significant. As with the circular bands connected by branching (Fig. 3a-b) and cruciform cells (Fig. 2a-b), the sharing of muscle fibers between adjacent bands can serve to coordinate contractile activity between different bands of visceral muscle, so long as there is a mechanism to pass excitation between fibers. As seen in Fig. 11c, it is possible to distinguish individual myofibrils that are shared by as many as four longitudinal bands. Such a shared fiber will contract with others in an individual band with which it is a constituent, and assist in propagating contraction with a portion of the remaining network as it runs between other bands.

The cruciform cells associated with the muscularis in the anterior region of the midgut may have a profound impact on midgut motility. In the anterior midgut, waves of peristaltic activity originating in the posterior midgut travel longitudinally from posterior to anterior (H. Onken, personal communication). A wave of contraction along a given longitudinal muscle band located on one of the lateral sides of the anterior midgut will likely encounter cruciform cells. As illustrated in Figure 12, such a wave of contraction could possibly be shunted along both circularly and longitudinally oriented bands at these regions. This would allow for many of the bands associated with the cruciform region to contract in concert. The result would be concurrent movement of several muscle bands, running in both the circular and longitudinal orientation, upon minimal initial stimulation. It is presently unknown what effect, if any, the proposed shunting of contractile inertia throughout the cruciform region containing will have on the propagation of contractile inertia along the longitudinal axis.

FIGURE 12.

Illustration of excitation traveling along a longitudinal muscle band (L) associated with cruciform regions of muscularis. Circular muscle (C), anterior, and posterior orientation is indicated.

The cruciform cells appear to be associated with the incomplete muscle bands observed in the anterior midgut (Figure 2, Figure 5). Seron et al. (2004) discuss the location of carbonic anhydrase positive muscle bands along the lateral sides of the anterior midgut. The incomplete muscle bands are observed in this same locale. It is possible that the carbonic anhydrase immunoreactivity is associated with either the incomplete muscle bands or bands associated with the cruciform cells. Immunolocalization studies focusing on these regions of the muscularis may provide significant information.

In these studies we made no attempt to control muscle length or state of activation during fixation, and it can be assumed that the muscle was fixed in a contracted state. Even so, the degree of filament overlap throughout the tissue is striking. Both I bands (sarcomere zones containing only actin) are either short or absent in many specimens and A bands (regions of actin and myosin filament overlap) are difficult to discern in longitudinal sections of circular muscle. Regions containing both actin and myosin filaments, however, are often readily apparent in many longitudinal muscle fibers when in cross section.

Similar findings have been reported in other insect species. Goldstein et al. (1971) reported that, in the visceral muscle of larval D. melanogaster, H bands (containing myosin only) were ambiguous in longitudinal section. A bands were highly variable, as the thinner actin filaments were scattered in a highly random manner throughout the fiber. The visceral muscle associated with the seminal vesicle in Carausius morosus exhibits H bands which are unclear in longitudinal section as well as highly distinct but erratic Z bands (Smith et al., 1966). The proctodeal muscle fibers in Periplaneta americana contain sarcomeres with equally ambiguous A and I bands in longitudinal section, despite the evidence of actin and myosin overlap in cross section (Nagai et al., 1974). H bands were not observed in this species.

Additional evidence that the high levels of filament overlap we observed are characteristic of insect visceral muscle is apparent in the thin: thick filament ratios found in a number of earlier reports. For example, the muscularis of the seminal vesicle of the stick insect Carausius morosus exhibits up to 12 actin filaments per individual myosin filament (Smith et al., 1966). In cockroach proctodeum severe changes in the degree of filament overlap in the A zone accompany contraction (Nagai et al., 1974); a mean ratio of 4 actin filaments per myosin filament is observed when the muscle is in the relaxed state, while a mean of 9.8 actin filaments per myosin filament is observed in contracted muscle.

The gaps in phalloidin-actin binding in some circular muscle bands indicated in Figures 11a and 11c are enigmatic. While these gaps are not dissimilar in size from the ovoid swellings observed in some scanning electron micrographs and presumed to accommodate muscle fiber nuclei (Fig. 2a-b), it has been observed under the transmission electron microscope that contractile elements are present in the region immediately surrounding many muscle fiber nuclei. Both I bands (containing actin only) and H bands (containing myosin) are difficult to discern in many observed longitudinal and circular muscle bands, and in many specimens the region of actin and myosin overlap appears to occupy the vast majority of the sarcomere length. It is unclear if these gaps in phalloidin binding represent sporadic yet large H bands not yet detected via transmission electron microscopy or some other phenomenon.

We found perforated Z discs suggestive of supercontractility in longitudinal sections of circular muscle (Fig. 8a, 8d). As illustrated in these images, the thicker myosin filaments penetrate through these perforations and extend into the neighboring sarcomere. These findings are similar to those of Jones et al. (1968), who identified discontinuous Z discs in the muscularis of the gastric ceca in 4th instar Aedes aegypti larvae.

Conventionally, striated muscle has been regarded as adapted for delivering maximal force over a rather narrow working range, since the Z-disks limit sarcomere shortening to at most about 50% of rest length. In this view, the supercontracting muscles of insects would correspond to vertebrate smooth muscle, in that in both cases the structure of the contractile machinery seems to permit force development to be sustained over a wide range of fiber lengths. For example, in his study of visceral muscle in the adult tsetse fly, Rice (1970) identified supercontracting elements in the intrinsic visceral muscle of the esophagus and midgut, and speculated that the supercontraction of this muscle represents the resting state and allows for extensive increases in muscle length to accommodate the changes in midgut diameter following consumption of a blood meal. In the case of the larval mosquito gut, supercontraction would seem imperative only for circular fibers, since the animal’s body structure would seem to allow only modest changes in the length of the gut, and this is consistent with our observation that perforated sarcomeres were largely confined to the circular fibers.

The visceral muscle of Aedes aegypti larvae exhibits only widely scattered transverse tubules and essentially no structures recognizable as cisternae of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. The scarcity of these structures is extreme even by comparison with the adult mosquito Anopheles quadramaculatus (Schaeffer et al., 1967) or larval fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster (Goldstein et al., 1971). However, reduced sarcoplasmic reticulum cisternae are common to many insect visceral and slow-twitch skeletal muscles (Klowden 2002). Due to their decreased sarcoplasmic reticulum, these muscle fibers are less able to sequester cytoplasmic Ca2+. The consequent ‘increase’ in free cytoplasmic Ca2+ (due to the inability of the fiber to sequester it) is associated with the enhanced ability to sustain prolonged tension at a fixed muscle length. This situation, together with the very small diameter of the fibers, would also be consistent with an important role of extracellular Ca++ in excitation-contraction coupling. Wilcox et al. (1995) found that proctolin-stimulated contraction in muscle associated with the locust (Locusta migratoria) oviduct depends on extracellular Ca2+, as does the proctolin-induced response of the hindgut muscularis in the cockroach Periplaneta americana (Cook et al., 1985).

4.2 Implications for Growth and Development of the Larval Gut

San Martin et al. (2001) report the significance of both founder and fusion competent myoblasts in the developing muscularis of Drosophila embryos. These embryonic cells seed the formation and subsequent fusion of distinct visceral muscle fibers during the embryonic period. The longitudinal and circular muscle bands each have their own class of founders. Each type of distinct muscle is seeded by a different set of embryonic precursors. These precursors form syncyctial muscle fibers, in Drosophila, which persist through metamorphosis (Klapper et al., 2001). This may contribute to the pattern of overlapping bands seen in many regions of the muscularis of Drosophila larvae. It is presently unknown if other dipterans, such as Aedes aegypti, also develop these primordial muscle fibers; however, the observation of overlapping bands of muscle indicates the possibility of such a common developmental element. It is not apparent whether cruciform cells arise as a result of the fusion of distinct circular and longitudinal myoblasts or if there is a third class of founders responsible for their initiation. The formation of the visceral muscle grid is an essential precursor for subsequent morphogenic events, since the muscularis serves as a scaffold for the outgrowth of the gut’s innervation and tracheation in larval insects including Manduca sexta (Copenhaver 1993; Copenhaver et al., 1996).

In the anterior midgut, a significant decrease in the number of circular bands per 100 μm gut length occurs between the second and third larval instars. This decrease in circular band density is seen in conjunction with an increased spacing, in μm, between them. While the changes in circular muscle band density in the posterior midgut are not significant, an increase in both band spacing and width takes place (as seen in the anterior midgut). These changes occur in conjunction with an overall increase in the length of the midgut as the animal develops. The increase in distance between the circular bands of muscle, as well as the wishbone pattern of circular band branching and merging, indicate that increases in the length of the gut are accommodated without requiring the significant generation of additional complete bands of circular muscle.

Both the number of and the distance between longitudinal bands of the anterior midgut increases as animals pass from the second to third larval instar. The distance between longitudinal muscle bands changes by the fourth larval instar, with a decrease in this distance in the posterior midgut. This phenomenon may be the result of either development and growth or artifact arising as the result of dissection, removal of gut contents, and fixation.

The width of both longitudinal and circular muscle bands increases, in the anterior and posterior regions of the midgut, by the fourth instar relative to the second instar. This is highly indicative of muscle fiber growth and may be due to both the increase in the density of contractile elements within fibers as well as the volume of those regions of the sarcoplasm unoccupied by such filaments.

To summarize the implications of these results: in principle, growth of the midgut could involve the generation of additional muscle bands, which would tend to maintain the dimensions of individual grid squares while increasing the number of squares. Alternatively, the number of fibers might be fixed; increase in gut surface could be accommodated by an increase in the dimensions of grid squares without an increase in the number of the squares. Although these two growth modes are not necessarily mutually exclusive, our observations are most consistent with a mode in which the number of circular and longitudinal muscle bands remain relatively stable across larval instars, while the mass and force potential of the muscularis grows through increases in the diameter of the individual fibers.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dr. Christine Davitt, Dr. Valerie Lynch-Holm, Dr. Vincent Franceschi (deceased), and the staff of the Franceschi Microscopy and Imaging Center (Washington State University, Pullman, WA) for their input during the development of microscopy related protocols. Dr. Marc Klowden (University of Idaho, Moscow, ID) provided Aedes aegypti eggs. This project was funded by the National Science Foundation, (Grant #IBN-0091208), National Institutes of Health (R01-AI06346301AZ), and William and Charles McNeil Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- Clark TM, et al. Additional Morphological and Physiological Heterogeneity Within the Midgut of Larval Aedes aegypti Revealed By Histology, Electrophysiology, and Effects of Bacillus thuringiensis Endotoxin. Tissue and Cell. 2005;37:457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TM, Koch A, Moffett DF. The Electrical Properties of the Anterior Stomach of the Larval Mosquito Aedes aegypti. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2000;203:1093–1101. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.6.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements AN. The Biology of Mosquitoes. Volume One. Chapman and Hall; New York, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver PF, Horgan AM, Combes S. An Identified Set of Visceral Muscle Bands is Essential for the Guidance of Migratory Neurons in the Enteric Nervous System of Manduca sexta. Developmental Biology. 1996;179:412–426. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver PF. Origins, Migration, and Differentiation of Glial Cells in the Insect Enteric Nervous System From a Discrete Set of Glial Precursors. Development. 1993;117:59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cook BJ, et al. The Role of Proctolin and Glutamate in the Excitation Contraction Coupling of an Insect Visceral Muscle. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1985;80:65–73. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(85)90133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein MA, Burdette WJ. Striated Visceral Muscle of Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of Morphology. 1971;134:315–334. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051340305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JC, Zeve VH. The Fine Structure of the Gastric Ceca of Aedes aegypti Larvae. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1968;14:1567–1575. [Google Scholar]

- Jones JC. The Anatomy and Rhythmical Activities of the Alimentary Canal of Anopheles Larvae. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1960;53:459–474. [Google Scholar]

- Klapper Robert, et al. A New Approach Reveals Syncyntia Within the Visceral Musculature of Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 2001;128:2517–2524. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.13.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klowden Marc. Physiological Systems in Insects. Academic Press, Elsevier Science; New York: 2002. pp. 278–282. [Google Scholar]

- Moffett SB, Moffett DF. Comparison of Immunoreactivity to Serotonin, FMRF-amide and SCPb in the Gut and Visceral Nervous System of Larvae, Pupae, and Adults of the Yellow Fever Mosquito Aedes aegypti. Journal of Insect Science. 2005;5:20. doi: 10.1093/jis/5.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Graham WG. Insect Visceral Muscle. Fine Structure of the Proctodeal Muscle Fibers. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1974;20:1999–2013. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(74)90107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien JF. Development of the Muscular Network of the Midgut in the Larval Stages of the Mosquito Aedes aegypti. Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 1965;73(4):226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Onken H, Moffett SB, Moffett DF. The Transepithe lial Voltage of the Isolated Anterior Stomach of Mosquito Larvae (Aedes aegypti): Pharmacological Characterization of the Serotonin-Stimulated Cells. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2004;207:1779–1787. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken H, Moffett SB, Moffett DF. The Anterior Stomach of Larval Mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti): Effects of Neuropeptides on Transepithelial Ion Transport and Muscular Motility. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2004a;207:3731–3739. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne MP. Supercontraction in the Muscles of the Blowfly Larva: an Ultrastructural Study. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1967;13:1471–1482. [Google Scholar]

- Park SS, Shahabuddin M. Structural Organization of Posterior Midgut Muscles in Mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae. Journal of Structural Biology. 2000;129:30–37. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay JA. Osmotic Regulation in Mosquito Larvae. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1950;27(2)(2):145–157. doi: 10.1242/jeb.27.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice MJ. Supercontracting and Non-supercontracting Visceral Muscles in the Tsetse Fly, Glossina austeni. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1970;16:1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(70)90201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Martin Beatriz. A Distinct Set of Founders and Fusion-Competent Myoblasts Make Visceral Muscles in the Drosophila Embryo. Development. 2001;128:3331–3338. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.17.3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer CW, Vanderberg JP, Rhodin Johannes. The Fine Structure of Mosquito Midgut Muscle. Journal of Cell Biology. 1967;34:905–911. doi: 10.1083/jcb.34.3.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DS, Gupta BL, Smith U. The Organization and Myofilament Array of Insect Visceral Muscles. Journal of Cell Science. 1966;1:49–57. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox CL, Lange AB. Role of Extracellular and Intracellular Calcium on Proctolin-Induced Contractions in an Insect Visceral Muscle. Regulatory Peptides. 1995;56:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(95)00006-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]