Abstract

Src family nonreceptor tyrosine kinases are kept in a repressed state by intramolecular interactions involving the SH3 and SH2 domains of the enzymes. Ligands for these domains can displace the intramolecular associations and activate the kinases. Here, we carried out in vitro activation experiments with purified, downregulated hematopoietic cell kinase (Hck), a Src family kinase. We show that SH3 and SH2 ligands act cooperatively to activate Src family kinases: the presence of one ligand lowers the concentration of the second ligand necessary for activation. To confirm the findings in intact cells, we studied Cas, a Src substrate that possesses SH2 and SH3 ligands. In contrast to wild-type Cas, mutant forms of Cas lacking the SH3- or SH2-ligands were unable to stimulate Src autophosphorylation when expressed in Cas-deficient fibroblasts. Cells expressing the Cas mutants also showed decreased amounts of activated Src at focal adhesions. The results suggest that proteins containing ligands for both SH3 and SH2 domains can produce a synergistic activation of Src family kinases.

Keywords: Src, tyrosine kinase, SH3 domain, SH2 domain, cooperativity

Introduction

Eukaryotic signaling proteins are typically composed of multiple modular domains. Communication between domains of a signaling protein is often necessary for proper regulation, and for precise and timely responses to stimuli. One mechanism for inter-domain communication is cooperativity, i.e., two structurally and functionally independent domains acting together synergistically to activate or inhibit the final output of the protein [1]. A well-studied example of a signaling protein that exhibits cooperativity is the Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein (WASP). WASP contains a verprolin cofilin acidic (VCA) domain that binds and activates the Arp 2/3 complex to nucleate actin filaments. In the absence of stimulation, the VCA domain is kept in an auto-inhibited state by intramolecular interactions with the G protein binding/switching domain (GBD) and a basic domain (B). The ligands for the GBD and B domains (Cdc42 and PIP2, respectively) are relatively poor activators of WASP individually. When both ligands are bound to WASP, they synergistically stimulate the actin polymerization activity of the VCA domain [2].

Src family tyrosine kinases are allosteric enzymes that are involved in a diverse array of signaling pathways ranging from proliferation and differentiation to cell death [3–5]. Src family kinases have a conserved domain arrangement: from N to C terminus, they contain a unique region, followed by SH3, SH2, and kinase catalytic domains. The structures of the down-regulated Src family kinases Hck and Src show that the kinase domain is kept in a repressed state by a series of intramolecular interactions [6–8]. The SH2 and SH3 domains are bound to their ligands on the opposite face of the kinase domain from the catalytic cleft. The SH2 domain forms an intramolecular interaction with the C-terminal phospho-tyrosine 527, while the SH3 domain interacts with a polyproline type II helix in the SH2-kinase linker region. Binding of SH3 or SH2 ligands leads to release of these interactions, autophosphorylation of activation loop tyrosine 416, and increased kinase activity [9–14]. When the SH3 and SH2 domains are bound to their intramolecular ligands simultaneously, the connector between them forms an “inducible snap lock” that couples the domains together [15–17]. This suggests that SH3 and SH2 ligands could produce cooperative activation of Src kinases [18]. Consistent with this, a peptide containing both SH3- and SH2-binding sites binds to Src with higher affinity than a peptide containing an SH2 ligand alone [19]. Furthermore, many known Src family kinase substrates have ligands for both the SH3 as well as the SH2 domain of the kinase. For the Src substrates Cas and Sin, interaction with both the SH3 and SH2 domains leads to maximal downstream signaling as reported by substrate phosphorylation and transcriptional activation [14, 20, 21].

In this paper, we tested the hypothesis that SH3 and SH2 ligands act cooperatively to activate Src family kinases. This possibility has not been formally tested, i.e., it has not been determined whether the presence of one ligand lowers the concentration of the second ligand necessary for activation. We carried out kinetic studies using purified down-regulated Hck and synthetic SH3 and SH2 domain ligand peptides as activators. We observed a decrease in the Kact of an SH2 ligand in the presence of SH3 ligand, and vice-versa. To study the importance of cooperativity in intact cells, we measured Src autophosphorylation in cells expressing wild-type Cas, or mutants lacking SH3 and SH2 domain binding sequences.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids

The wild-type, Y668F, and PPX mutant forms of Cas were expressed as YFP fusions, as described previously [22]. The PPX mutant contains P640S, P642G, and P645G mutations in the SH3-binding region of Cas. The Y668F/PPX double mutant was made by sequential site-directed mutagenesis of the pCDNA6-YFP-Cas construct using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene). FLAG-tagged wild-type c-Src was constructed by cloning the Src DNA sequence into the NotI-BamHI site of p3Xflag-CMV-7.1 (Sigma).

Protein Purification and Kinase assays

Down-regulated Hck was purified from Sf9 cells as described [9]. The following peptides were used in these studies: substrate peptide, AEEEIYGEFEAKKKKG; SH3 ligand, SPPTPKPRPPRP; SH2 ligand, EPQpYEEIPIKQ [9, 10]. Kinase assays were performed using a continuous spectrophotometric assay, where production of ADP is coupled to oxidation of NADH and is measured as a decrease in absorbance at 340nm. For the kinase reactions, autophosphorylated down-regulated Hck was generated by pre-incubation with 500μM ATP at 4°C for 30 minutes. The autophosphorylated Hck was used at a final concentration of 15nM and varying concentrations of SH3 ligand peptide (10μM–620μM) and SH2 ligand peptide (0.5μM–64μM) were used as activators in the assay. For assays with two ligands, Hck was pre-incubated with a fixed concentration of the first ligand for 2 minutes at room temperature, then the second ligand was added at varying concentrations in the spectrophotometric assay. The activation constant, Kact, was determined by non-linear regression analysis of the rates as a function of ligand concentration as described (9). The equation used for analysis was

where Va = velocity measured in the presence of variable ligand minus the velocity measured in the absence of ligand, Vact = maximal activated velocity in the presence of variable ligand minus the velocity measured in the absence of ligand, and [L] is the ligand concentration for which Kact is being determined. For experiments with two ligands, the velocity measured in the absence of the variable ligand was determined in the presence of the other ligand.

Cell culture, immunoblotting, and immunoprecipitation

Cas−/− cells were maintained in low glucose DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100U/ml penicillin and 100U/ml streptomycin in a 37° C, 5% CO2 incubator. The cells were plated at a density of 1×106 cells per 100mm plate. The cells were transiently transfected with Src (0.5–1μg) and Cas (2–5μg) using TransIT (Mirus). The cells were harvested 48 hours after transfection in RIPA buffer. The lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and were subjected to immunoblot analysis with α-pY416 (Biosource), α-Flag (Sigma), α-Cas (Santa Cruz) and α-Tubulin (Sigma) antibodies. For co-immunoprecipitation experiments, cells were lysed in buffer containing 50mM Tris pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, 1mM sodium vanadate, protease inhibitors, and 1% NP-40. Lysates (500μg) were pre-cleared for 1 hour at 4°C and then subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with 2μg of α-Cas N17 antibody (Santa Cruz) overnight at 4°C. The IP samples were separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE and were subjected to immunoblot analysis with α-Flag and α-Cas N17 antibodies.

Immunofluorescence analysis

Cas−/− cells or Cos7 cells were grown on cover slips and transiently transfected with Src and YFP- Cas (wild-type or mutants). Cells were washed in 1X phosphate buffered saline and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin. α-pY416 antibody was used at a dilution of 1:200 and Texas Red conjugated α-rabbit antibody was used as 6 secondary antibody. Nuclei were visualized by staining with DAPI. Cells were analyzed using an inverted microscope (Zeiss 200M) using filters for YFP, DAPI and Texas Red. Images were analyzed using AxioVision software (v. 4.5). Only YFP positive cells were analyzed for activated Src in the focal adhesions. Approximately 60–70% YFP positive cells had the phenotype presented in Figure 3. Differential interference contrast (DIC) and YFP images of Cas−/− cells expressing YFP tagged wild-type Cas or its mutants were obtained using a 63X oil objective and YFP filter.

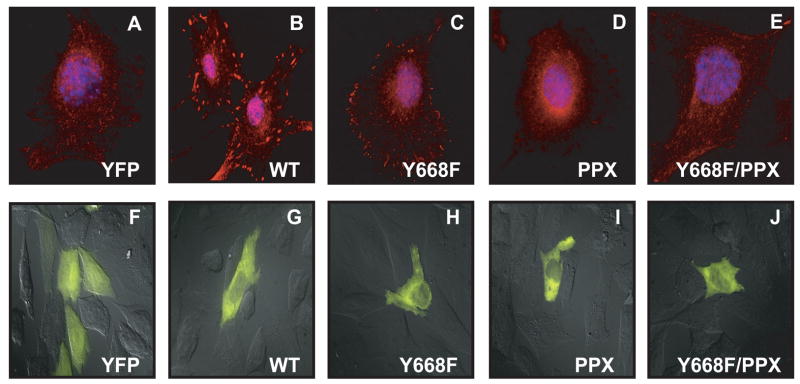

Figure 3.

Decreased amounts of activated Src in cells expressing Cas mutants. Cas−/− cells were co-transfected with Src and Cas (wild-type or mutants). Cas expressing cells were identified as YFP positive and analyzed for Src activation. Cells were immunostained 24 hours after transfection with anti-pY416 antibody to visualize activated Src. Nuclei were visualized with DAPI. [A]: YFP vector control. [B]: wild-type Cas. [C]: Y668F Cas mutant. [D]: PPX mutant. [E]: Y668F/PPX double mutant. [F]–[J]: Superimposed DIC and YFP images of Cas−/− cells expressing YFP-tagged WT or mutant forms of Cas. A similar cytosolic distribution was observed for all forms of Cas.

Results

Cooperative activation by SH3 and SH3 ligands

To test for cooperativity, we expressed and purified the down-regulated form of the Src kinase Hck. In this form of the enzyme, the SH3 and SH2 domains are engaged with their intramolecular ligands [6–8, 15, 18, 23]. Hck can be activated by incubation with a synthetic peptide containing the optimal SH2-binding sequence pYEEI, or with a proline-rich SH3 binding peptide [9, 11].

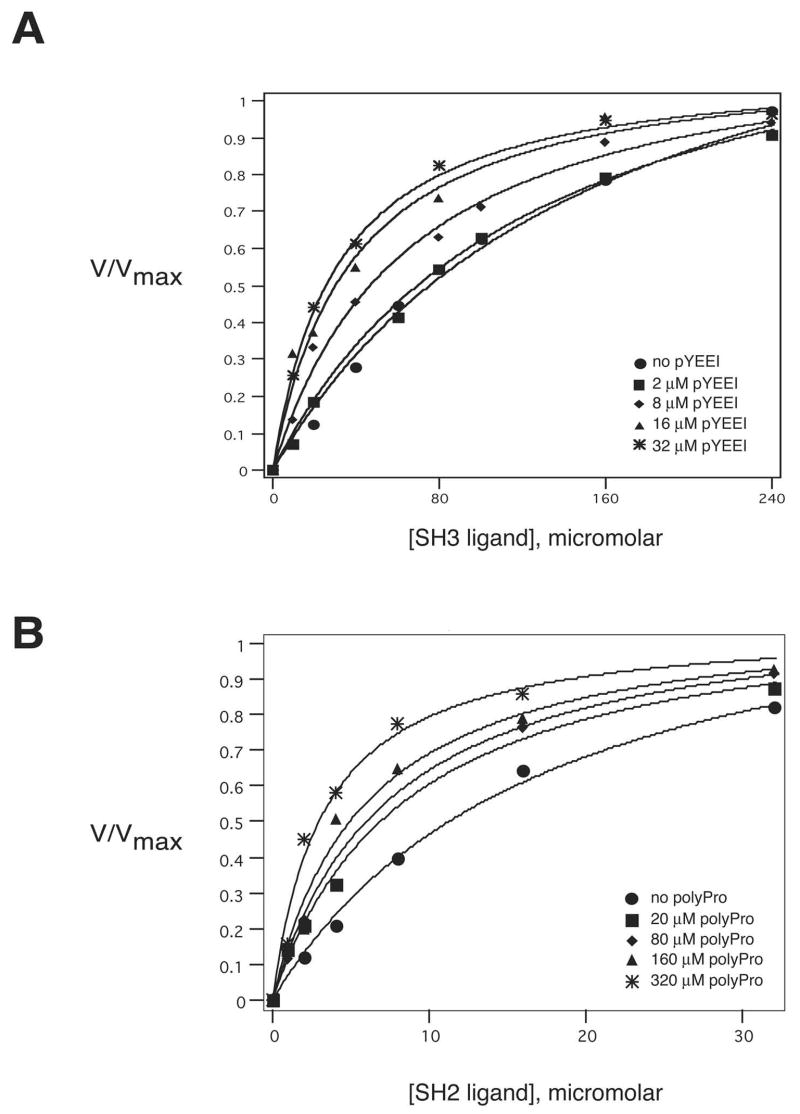

We performed spectrophotometric kinase assays to determine values of Kact, the concentration of ligand required for half-maximal activation of Hck. When measured individually, the Kact values for the SH2-binding and SH3-binding peptides were 18 μM and 159 μM, respectively (Tables 1 and 2). If the SH3 and SH2 domains function cooperatively to inhibit kinase activity, disrupting one intramolecular interaction should weaken the other one. Thus, addition of one ligand (e.g., the SH2 ligand) should decrease the concentration of the other ligand (the SH3 ligand) needed for half-maximal activation of Hck. In our experiments, the Kact for SH3 ligand decreased from 159 μM to 31 μM in the presence of increasing concentrations of SH2 ligand (Table 1, Figure 1A). No additional decrease in the Kact for SH3 ligand was observed with concentrations of SH2 ligand higher than 32 μM. Next, we carried out the reciprocal measurements of Kact for SH2 ligand in the presence of increasing concentrations of the SH3-binding peptide. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 1B, we measured a gradual decrease in the Kact of SH2 ligand as the concentration of SH3 ligand was increased. The Kact decreases to a minimum of 3.3μm in the presence of 320μM SH3 ligand peptide. Our kinetic analysis supports the hypothesis that SH3 and SH2 ligands act cooperatively to activate the kinase. Therefore, a lower concentration of a protein capable of binding to both the SH3 and SH2 domains would be required to activate Src than of a protein with a single ligand sequence.

Table 1.

Activation constants for SH3 ligand binding to Hck in the presence of fixed concentrations of SH2 ligand

| SH2 ligand concentration (μM) | Kact (μM) for SH3 ligand |

|---|---|

| 0 | 159 (+/− 23) |

| 2 | 126 (+/− 16) |

| 8 | 66 (+/− 6) |

| 16 | 38 (+/− 6) |

| 32 | 31 (+/− 2) |

Table 2.

Activation constants for SH2 ligand binding to Hck in the presence of fixed concentrations of SH3 ligand

| SH3 ligand concentration(μM) | Kact (μM) for SH2 ligand |

|---|---|

| 0 | 18 (+/− 1.4) |

| 20 | 8.6 (+/− 0.6) |

| 80 | 7.4 (+/− 0.4) |

| 160 | 5.9 (+/− 0.8) |

| 320 | 3.3 (+/− 0.5) |

Figure 1.

Cooperativity between the SH3 and SH2 domains of Hck. [A] Hck activity was measured using the continuous spectrophotometric assay. Assays were carried out in the presence of varying concentrations of SH3 ligand at fixed concentrations of SH2 ligand. [B] Hck activity was measured in the presence of varying concentrations of SH2 ligand at fixed concentrations of SH3 ligand. Activation constants were determined as described in the text.

Importance of the SH2/SH3 ligand sequences in Cas for Src activation

Next, we wished to test for activation of Src kinases by a combination of SH3 and SH2 ligands in intact cells. Cas is an adaptor protein that is involved in cell migration and integrin signaling [21, 24–27]. It has been extensively characterized as a substrate of Src family kinases [20, 28–31]. Cas has a Src binding sequence (SBS) near its C-terminus that contains a ligand for the SH3 domain (RPLPSPP), followed by a 668YDYV motif which, when phosphorylated at Y668, can interact with the SH2 domain (Figure 2A). It has been shown that Src binds to Cas through its SH3 and SH2 domains, and the most important interaction is between the SH3 domain and the polyproline sequence [22, 31]. This binding leads to processive phosphorylation of 15 tyrosine residues in the substrate region of Cas by Src family kinases [22, 32, 33]. Since Cas has the potential to disrupt both SH3 and SH2 domain mediated intramolecular interactions in Src family kinases, it can function as an activator of Src family kinases [20, 22, 24].

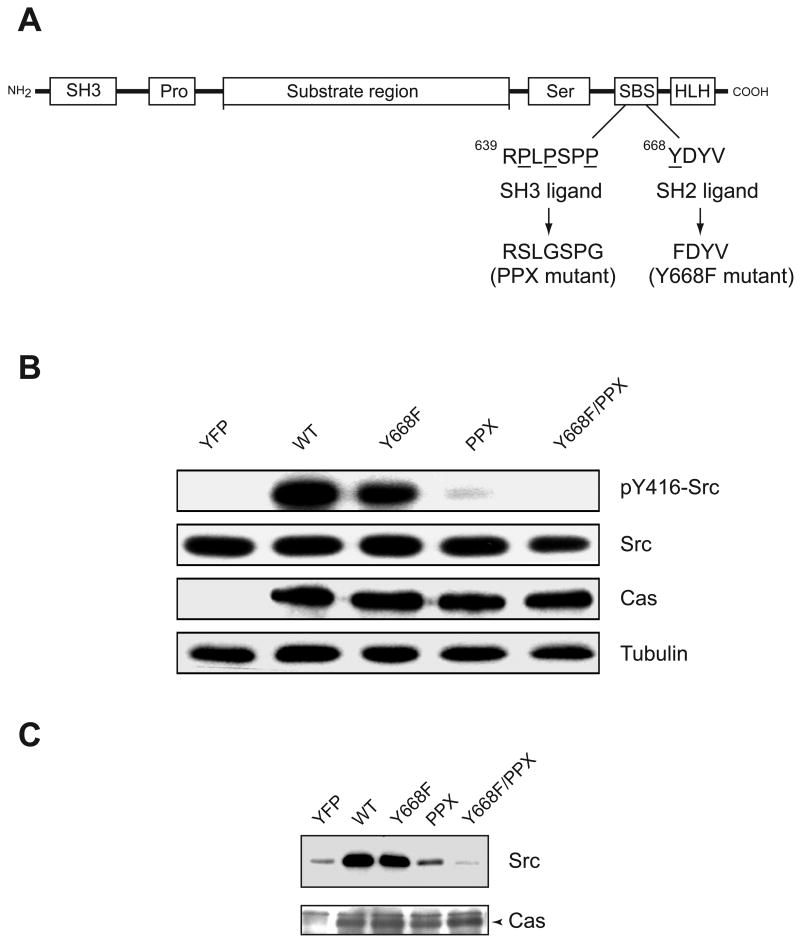

Figure 2.

(A) Domain arrangement of Cas showing the SH3 domain (SH3), proline-rich region (Pro), substrate region containing 15 repeats of YXXP, serine-rich region (Ser), C-terminal Src binding sequence (SBS), and helix-loop-helix region (HLH). Within the SBS, the sequences of the Src SH3 ligand (RPLPSPP) and SH2 ligand (YDYV) are shown. The PPX mutant carries mutations in the proline rich sequence (underlined) that impair interaction with the SH3 domains of SFKs. The Y668F mutation (underlined) blocks interaction with the SH2 domain of Src. The Y668F/PPX double mutant has both the binding sequences mutated. (B) Autophosphorylation of Src in Cas−/− cells. Cells expressing wild-type or mutant forms of Cas (or vector control) were lysed and analyzed by SDS-PAGE with Western blotting. The membrane was probed with antibodies for autophosphorylated Src (pY416), then stripped and reprobed with antibodies against total Src, Cas, and tubulin as a loading control. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation of Src and Cas. Cas−/− cells expressing wild-type or mutant forms of Cas (or vector control) were lysed and subjected to anti-Cas immunoprecipitation reactions. Proteins in the precipitates were transferred to membrane and detected by anti-FLAG Western blotting (for Src). The membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-Cas antibody (the arrowhead indicates the position of Cas).

In order to study the cellular interactions between Src and Cas, we employed three Cas mutants that are defective in interaction with Src (Figure 2A): (1) CasY668F, in which the phosphotyrosine residue necessary for SH2 interaction is removed; (2) CasPPX, in which proline residues critical for SH3 binding are mutated; and (3) a CasY668F/PPX double mutant which can bind neither the SH3 nor the SH2 domain of Src. To eliminate the contribution of wild-type Cas, we expressed the mutant forms of Cas in fibroblasts derived from Cas-knockout mice.

We co-expressed Src together with Cas (wild-type or mutants) in Cas−/− cells and analyzed for Src activation using a phosphospecific antibody for Y416 in the activation loop. In the presence of wild-type Cas, Src was significantly autophosphorylated as indicated by anti-pY416 immunoblotting (Figure 2B). There was a small decrease in autophosphorylation of Src in cells expressing the Y668F form of Cas, and a more significant decrease in cells expressing Cas-PPX (Fig. 2B). The Y668F/PPX double mutant was similar to vector control, with no detectable autophosphorylation of Src (Figure 2B). These results provide further support to our hypothesis that the SH3 and SH2 domains act cooperatively in regulating Src family kinases. To analyze Src-Cas binding directly in these cells, we immunoprecipitated Cas and measured the amounts of associated Src (Fig. 2C). The PPX and Y668F/PPX mutants were defective in their ability to bind Src, consistent with our previous in vitro phosphorylation experiments and yeast two-hybrid studies showing the importance of SH3-mediated interactions between Src and Cas [22].

Activated Src in focal adhesions

Integrin signaling leads to activation of Src and Src-Cas interactions at focal adhesions [34–37]. We performed immunofluorescence analysis with anti-pY416 antibody to examine the activation status of Src in focal adhesions in Cas−/− cells co-expressing Src and wild-type Cas or its mutants. We analyzed YFP positive cells to identify Cas expressing cells. Similar to wild-type Cas, the mutant forms of Cas showed a general cytoplasmic distribution (Figs. 3F–J). Cells expressing YFP alone had no activated Src in focal adhesions (Fig. 3A), while in WT Cas-expressing cells Src was active and localized to focal adhesions (Fig. 3B). Src activation was somewhat less pronounced for Y668F compared to wild type Cas (Fig. 3C). The decrease in activated Src in the focal adhesions was more dramatic for Cas-PPX compared to WT Cas (Fig. 3D). Cells expressing the Y668F/PPX double mutant were similar to YFP expressing cells with minimal active Src in focal adhesions (Fig. 3E). We also observed similar results in Cos7 cells (data not shown).

Discussion

Our results provide support to the hypothesis that the SH3 and SH2 domains of Src family kinases act in a cooperative manner to repress the kinases. Src family kinases are regulated by intramolecular SH3 and SH2 domain mediated interactions, and it has been shown previously that the kinase can be activated by disruption of these SH3-linker and SH2-pTyr527 interactions [11–14]. The individual SH2 and SH3 ligands can activate Src kinases; here, we show that if one ligand is prebound to Hck, the autoinhibited conformation is destabilized and binding of the second ligand is enhanced. This is reflected in a decrease in the concentration of the second ligand necessary for half maximal activation of Hck (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 1). Our results are in accord with targeted molecular dynamics simulations of the closed form of Src, which suggest that the SH3 and SH2 domains act in concert to repress kinase activity [16]. In contrast, the activities of mutant forms of Hck expressed in fibroblasts have led to the suggestion that SH3-based activation and SH2-based activation are independent events that lead to distinct activated states [38, 39]. It is possible that the SH3-activated and SH2-activated states, which are presumably transient in our in vitro studies, are populated more fully in the cell due to the presence of SH2- and SH3-associated proteins.

In the cellular context, many natural activators of Src family kinases contain tandem SH3 and SH2 ligands. A sub-group of these proteins are SFK substrates which activate Src by disruption of the intramolecular interactions, and are subsequently targeted for phosphorylation while bound to the SH3 and SH2 domains [23]. A few examples of such SFK substrates are Cas, FAK, Sam68 and Sin [19, 31, 40–43]. The autophosphorylation of FAK at Y397 is increased by integrin-dependent cell adhesion [35, 37]. This autophosphorylation site acts as a ligand for the SH2 domain of Src. In addition, residues 368–378 of FAK serve as a ligand for the SH3 domain of Src [19]. Thus, these two sequences in FAK cooperate to generate activated Src at the focal adhesions. In the case of Cas and FAK, co-expression with Src leads to enhanced phosphorylation of paxillin and other downstream targets [19, 20], but this effect was not observed for mutants deficient in Src binding. Similarly, expression of wild-type Sin (but not mutants defective in Src binding) led to increased Src-mediated transcriptional activation [14].

To test for cooperative activation of SFKs in intact cells, we examined the ability of Cas to promote Src autophosphorylation. Expression of wild-type Cas led to an increase in Src autophosphorylation (Fig. 3). Mutations of the SH3- or SH2-binding sequences interfered with the ability of Cas to activate Src. This effect was most pronounced for the PPX and Y668F/PPX mutants, consistent with our previous studies showing that the poly-proline sequence of Cas is the major determinant for Src binding [22]. In the previous studies, removal of the poly-proline sequence from Cas prevented tyrosine phosphorylation (including, presumably, phosphorylation of Y668). Cells expressing the PPX and Y668F/PPX mutants also showed low levels of activated Src in focal adhesions (Fig. 4). The higher potency of the combined SH3-SH2 ligand sequences for Src activation suggests that many cellular activators will contain dual ligands. Consistent with this, activated Src is associated with subcellular sites (e.g., focal adhesions) that are known to contain a high local concentration of SH3 and SH2 ligands [4].

As noted by Lim and coworkers [44], cooperativity between modular domains in a signaling protein provides a mechanism for signal integration and amplification, allowing precise control of the output. For example, the presence of ligands for both the GBD and B domains of WASP leads to maximal signal amplification, while either ligand alone leads to sub-maximal activation [2]. The synergistic activation of WASP is therefore an example of “coincidence detection [45].” Coincidence detection is also seen in the case of protein kinase C, where the C1 and C2 domains require diacylglycerol and calcium, respectively, to bind to membranes. In general, cooperativity is maintained by a delicate balance of interactions between the domains and their ligands, and the pattern of regulation can be altered by slight changes in ligands and domains. Thus, cooperativity provides an evolutionary mechanism to adapt to changing environments [44]. Autoinhibition is widespread among signaling proteins [46], and the repressed states of many of the proteins depend on multiple binding sites, suggesting that many signaling systems may be regulated by cooperative interactions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Gordon for assistance with microscopy, and Xiaoling Wang for preliminary kinetic experiments. We thank Dr. Wendell Lim (University of California, San Francisco) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dueber JE, Yeh BJ, Bhattacharyya RP, Lim WA. Rewiring cell signaling: the logic and plasticity of eukaryotic protein circuitry. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:690–699. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prehoda KE, Scott JA, Mullins RD, Lim WA. Integration of multiple signals through cooperative regulation of the N-WASP-Arp2/3 complex. Science. 2000;290:801–806. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5492.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsons SJ, Parsons JT. Src family kinases, key regulators of signal transduction. Oncogene. 2004;23:7906–7909. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown MT, Cooper JA. Regulation, substrates and functions of src. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1287:121–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sicheri F, Moarefi I, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the Src family tyrosine kinase Hck. Nature. 1997;385:602–609. doi: 10.1038/385602a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu W, Doshi A, Lei M, Eck MJ, Harrison SC. Crystal structures of c-Src reveal features of its autoinhibitory mechanism. Mol Cell. 1999;3:629–638. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu W, Harrison SC, Eck MJ. Three-dimensional structure of the tyrosine kinase c-Src. Nature. 1997;385:595–602. doi: 10.1038/385595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter M, Schindler T, Kuriyan J, Miller WT. Reciprocal regulation of Hck activity by phosphorylation of Tyr(527) and Tyr(416). Effect of introducing a high affinity intramolecular SH2 ligand. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2721–2726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaFevre-Bernt M, Sicheri F, Pico A, Porter M, Kuriyan J, Miller WT. Intramolecular regulatory interactions in the Src family kinase Hck probed by mutagenesis of a conserved tryptophan residue. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32129–32134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moarefi I, LaFevre-Bernt M, Sicheri F, Huse M, Lee CH, Kuriyan J, Miller WT. Activation of the Src-family tyrosine kinase Hck by SH3 domain displacement. Nature. 1997;385:650–653. doi: 10.1038/385650a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briggs SD, Sharkey M, Stevenson M, Smithgall TE. SH3-mediated Hck tyrosine kinase activation and fibroblast transformation by the Nef protein of HIV-1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17899–17902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X, Brodeur SR, Gish G, Songyang Z, Cantley LC, Laudano AP, Pawson T. Regulation of c-Src tyrosine kinase activity by the Src SH2 domain. Oncogene. 1993;8:1119–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexandropoulos K, Baltimore D. Coordinate activation of c-Src by SH3- and SH2-binding sites on a novel p130Cas-related protein, Sin. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1341–1355. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.11.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sicheri F, Kuriyan J. Structures of Src-family tyrosine kinases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:777–785. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young MA, Gonfloni S, Superti-Furga G, Roux B, Kuriyan J. Dynamic coupling between the SH2 and SH3 domains of c-Src and Hck underlies their inactivation by C-terminal tyrosine phosphorylation. Cell. 2001;105:115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonfloni S, Weijland A, Kretzschmar J, Superti-Furga G. Crosstalk between the catalytic and regulatory domains allows bidirectional regulation of Src. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:281–286. doi: 10.1038/74041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pellicena P, Miller WT. Coupling kinase activation to substrate recognition in SRC-family tyrosine kinases. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d256–267. doi: 10.2741/A725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas JW, Ellis B, Boerner RJ, Knight WB, White GC, 2nd, Schaller MD. SH2- and SH3-mediated interactions between focal adhesion kinase and Src. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:577–583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burnham MR, Bruce-Staskal PJ, Harte MT, Weidow CL, Ma A, Weed SA, Bouton AH. Regulation of c-SRC activity and function by the adapter protein CAS. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5865–5878. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.16.5865-5878.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hakak Y, Martin GS. Cas mediates transcriptional activation of the serum response element by Src. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6953–6962. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pellicena P, Miller WT. Processive phosphorylation of p130Cas by Src depends on SH3-polyproline interactions. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:28190–28196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100055200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller WT. Determinants of substrate recognition in nonreceptor tyrosine kinases. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:393–400. doi: 10.1021/ar020116v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouton AH, Riggins RB, Bruce-Staskal PJ. Functions of the adapter protein Cas: signal convergence and the determination of cellular responses. Oncogene. 2001;20:6448–6458. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamasaki K, Mimura T, Morino N, Furuya H, Nakamoto T, Aizawa S, Morimoto C, Yazaki Y, Hirai H, Nojima Y. Src kinase plays an essential role in integrin-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of Crk-associated substrate p130Cas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;222:338–343. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harte MT, Hildebrand JD, Burnham MR, Bouton AH, Parsons JT. p130Cas, a substrate associated with v-Src and v-Crk, localizes to focal adhesions and binds to focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13649–13655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honda H, Nakamoto T, Sakai R, Hirai H. p130(Cas), an assembling molecule of actin filaments, promotes cell movement, cell migration, and cell spreading in fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;262:25–30. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burnham MR, Harte MT, Bouton AH. The role of SRC-CAS interactions in cellular transformation: ectopic expression of the carboxy terminus of CAS inhibits SRC-CAS interaction but has no effect on cellular transformation. Mol Carcinog. 1999;26:20–31. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199909)26:1<20::aid-mc3>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakamoto T, Sakai R, Honda H, Ogawa S, Ueno H, Suzuki T, Aizawa S, Yazaki Y, Hirai H. Requirements for localization of p130cas to focal adhesions. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3884–3897. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nojima Y, Morino N, Mimura T, Hamasaki K, Furuya H, Sakai R, Sato T, Tachibana K, Morimoto C, Yazaki Y, et al. Integrin-mediated cell adhesion promotes tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas, a Src homology 3-containing molecule having multiple Src homology 2-binding motifs. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15398–15402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamoto T, Sakai R, Ozawa K, Yazaki Y, Hirai H. Direct binding of C-terminal region of p130Cas to SH2 and SH3 domains of Src kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8959–8965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patwardhan P, Shen Y, Goldberg GS, Miller WT. Individual Cas phosphorylation sites are dispensable for processive phosphorylation by Src and anchorage-independent cell growth. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20689–20697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602311200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberg GS, Alexander DB, Pellicena P, Zhang ZY, Tsuda H, Miller WT. Src phosphorylates Cas on tyrosine 253 to promote migration of transformed cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46533–46540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307526200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang J, Hamasaki H, Nakamoto T, Honda H, Hirai H, Saito M, Takato T, Sakai R. Differential regulation of cell migration, actin stress fiber organization, and cell transformation by functional domains of Crk-associated substrate. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27265–27272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar CC. Signaling by integrin receptors. Oncogene. 1998;17:1365–1373. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vuori K, Hirai H, Aizawa S, Ruoslahti E. Introduction of p130cas signaling complex formation upon integrin-mediated cell adhesion: a role for Src family kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2606–2613. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vuori K. Integrin signaling: tyrosine phosphorylation events in focal adhesions. J Membr Biol. 1998;165:191–199. doi: 10.1007/s002329900433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lerner EC, Trible RP, Schiavone AP, Hochrein JM, Engen JR, Smithgall TE. Activation of the Src family kinase Hck without SH3-linker release. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40832–40837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508782200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lerner EC, Smithgall TE. SH3-dependent stimulation of Src-family kinase autophosphorylation without tail release from the SH2 domain in vivo. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:365–369. doi: 10.1038/nsb782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor SJ, Shalloway D. An RNA-binding protein associated with Src through its SH2 and SH3 domains in mitosis. Nature. 1994;368:867–871. doi: 10.1038/368867a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor SJ, Anafi M, Pawson T, Shalloway D. Functional interaction between c-Src and its mitotic target, Sam 68. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10120–10124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.10120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richard S, Yu D, Blumer KJ, Hausladen D, Olszowy MW, Connelly PA, Shaw AS. Association of p62, a multifunctional SH2- and SH3-domain-binding protein, with src family tyrosine kinases, Grb2, and phospholipase C gamma-1. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:186–197. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lock P, Fumagalli S, Polakis P, McCormick F, Courtneidge SA. The human p62 cDNA encodes Sam68 and not the RasGAP-associated p62 protein. Cell. 1996;84:23–24. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80989-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lim WA. The modular logic of signaling proteins: building allosteric switches from simple binding domains. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:61–68. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McLaughlin S, Wang J, Gambhir A, Murray D. PIP(2) and proteins: interactions, organization, and information flow. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:151–175. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pufall MA, Graves BJ. Autoinhibitory domains: modular effectors of cellular regulation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:421–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.031502.133614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]