Abstract

GDNF, neurturin, and persephin are transforming growth factor β-related neurotrophic factors known collectively as the GDNF family (GF). GDNF and neurturin signal through a multicomponent receptor complex containing a signaling component (the Ret receptor tyrosine kinase) and either of two glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-linked binding components (GDNF family receptor α components 1 and 2, GFRα1 or GFRα2), whereas the receptor for persephin is unknown. Herein we describe a third member of the GF coreceptor family called GFRα3 that is encoded by a gene located on human chromosome 5q31.2–32. GFRα3 is not expressed in the central nervous system of the developing or adult animal but is highly expressed in several developing and adult sensory and sympathetic ganglia of the peripheral nervous system. GFRα3 is also expressed at high levels in developing, but not adult, peripheral nerve. GFRα3 is a glycoprotein that is glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-linked to the cell surface like GFRα1 and GFRα2. Fibroblasts expressing Ret and GFRα3 do not respond to any of the known members of the GDNF family, suggesting that GFRα3 interacts with an unknown ligand or requires a different or additional signaling protein to function.

The GDNF family (GF) of neurotrophic factors denotes a subfamily of proteins within the transforming growth factor β superfamily that currently contains three members: glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), discovered by its ability to maintain the survival of dopaminergic neurons of the embryonic ventral midbrain (1); neurturin (NTN), identified because of its survival-promoting properties on superior cervical ganglion neurons in culture (2); and persephin (PSP), discovered as the result of its homology to GDNF and NTN (3).

The sites of action of the GF ligands are broad and include neurons of the central and peripheral nervous system (CNS and PNS) and the developing kidney. In the CNS, sites of GF ligand action include dopaminergic midbrain neurons (1, 3–7), spinal and facial motor neurons (3, 8–10), Purkinje cells (11), and noradrenergic neurons of the locus ceruleus (12). Many sensory and autonomic ganglia of the PNS are also responsive to GDNF and NTN action, including neurons of dorsal root ganglion (DRG), superior cervical ganglion, trigeminal ganglion, and nodose ganglion (2, 13–15). Developing enteric neurons also respond to GDNF and NTN (R. Heuckeroth, personal communication). Finally, recent investigation has revealed that GF members also can act on ureteric bud branching in vitro (3, 16, 17). The intense study of GF ligand activities has revealed two generalized features: (i) GDNF and NTN qualitatively share activity on all responsive peripheral and central populations tested (2, 7); (ii) PSP shares only a subset of these activities, namely, those in the CNS (dopaminergic and motor neurons) and in the developing kidney (3).

The multicomponent GF receptor system recently characterized accounts for the overlap observed in GDNF and NTN action. The signaling component is the Ret receptor tyrosine kinase, and both GDNF and NTN can activate Ret in transfected cell lines and cultured superior cervical ganglion neurons (18, 19). Activation of Ret by GDNF or NTN requires the presence of a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked ligand binding coreceptor. Two GF receptor α components (GFRαs) have been identified, GFRα1 and GFRα2, and both can mediate GDNF or NTN signaling through Ret (20–23), although there is evidence that some specificity exists, with GFRα1 functioning preferentially as a GDNF receptor and GFRα2 as a preferential NTN receptor (7, 22, 23). The receptor for PSP is unknown; however, neither the Ret–GFRα1 nor Ret–GFRα2 receptor complexes are capable of forming functional PSP receptors. This indicates that an additional component is likely to be required for PSP signaling, either another PSP-specific coreceptor or an additional signaling component (3).

Herein we report the identification and characterization of GFRα3, a member of the GF receptor family. We found that GFRα3 is a GPI-linked glycoprotein like the related GFRα1 and GFRα2; however, GFRα3 was not capable of mediating Ret signaling for any of the known GF ligands in transfected fibroblasts. GFRα3 is expressed in developing and adult ganglia of the PNS but was not detected in the CNS, further emphasizing that GFRα3 likely does not participate in PSP signaling because PSP acts only on neurons in the CNS (3).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA Cloning, Sequence Analysis, Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization.

Sequence analysis and cloning was performed as described (22). Mouse expressed sequence tag (EST) clones obtained from the WashU-HHMI sequencing project were sequenced, and EST AA050083 contained a full-length GFRα3 cDNA. However, when it was compared with the sequences of other EST clones or mouse or human genomic sequence, it was found to contain a single nucleotide deletion. The mutation was corrected with PCR mutagenesis, and the complete cDNA was then cloned into the EcoRV site of pBluescript KS (Stratagene) and then into the HindIII and XbaI sites of pCMV-neo (24). To produce NHA-GFRα3, the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope was inserted into the cDNA between nucleotides 99 and 100 (amino acids 33 and 34) of the mouse GFRα3 sequence by PCR mutagenesis, cloned into pCMV-neo, and sequenced. Human and mouse GFRα3 genomic clones were obtained by screening P1 libraries with a PCR assay from the mouse and human GFRα3 cDNA sequences (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL). Portions of the human cDNA from 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (CLONTECH), genomic sequence, and PCR products from human cDNA libraries were used to obtain the sequence of human GFRα3. A human genomic P1 clone was labeled with biotin or digoxigenin (Random Primed DNA labeling kit, Boehringer Mannheim) and used for in situ hybridization of human chromosomes derived from methotrexate-synchronized normal peripheral lymphocyte cultures. Conditions of hybridization, detection of hybridization signals, digital image acquisition, processing, and analysis, as well as the procedure for direct visualization of fluorescent signals to banded chromosomes, were performed as described (22, 25) To identify exon–intron boundaries of GFRα2 and GFRα3, primers from exon sequence were used to sequence restriction fragments of the mouse P1 genomic clone subcloned into pBluescript. Junctions were identified by comparison of the mouse genomic and cDNA sequences.

Expression Analysis of GFRα3.

The human master RNA blot (MRB) was probed as described by the manufacturer’s instructions (CLONTECH) using a random hexamer 32P-labeled cDNA probe (nucleotides 266–802 of the human GFRα3 sequence). The blot was developed by using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics), and signals were quantified by using the imagequant software package. In situ hybridization analysis on fresh frozen tissue samples was performed as described (ref. 22 and J.P.G., R.H.B., P. Kotzbauer, P. Lampe, P. Osborne, J.M., and E.M.J., unpublished work). Sense and antisense 33P-labeled RNA probes were generated from a fragment of the mouse GFRα3 cDNA (nucleotides 107–291).

Stable Cell Line Production and Functional Assays.

NIH 3T3 fibroblasts (subclone MG87) expressing Ret, Ret/GFRα2, Ret/GFRα3, and Ret/NHA-GFRα3 were produced as described (19, 22). Briefly, a clonal fibroblast line stably expressing Ret was cotransfected with GFRα2, GFRα3, or NHA-GFRα3 and the SV2-HisD plasmid and selected in 2 mM histidinol (Sigma). Histidinol-resistant clones were isolated and screened for expression by Western (Ret and NHA-GFRα3) and Northern (GFRα2, GFRα3, and NHA-GFRα3) blotting. For tunicamycin treatment, cells were incubated in tunicamycin at 1 or 5 mg/ml for 24 hr, washed twice with ice-cold PBS, collected in SDS sample buffer, and electrophoresed on 10% polyacrylamide gels. Gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, placed in blocking solution [Tris-buffered saline (TBS)/0.1% Tween 20/5% dry milk] for 1 hr at 25°C, incubated in a 1:100 dilution of anti-HA antibody (mAb 12CA5 hybridoma supernatant) in blocking solution for 1 hr at 25°C and then washed in TBS/0.1% Tween. Blots were incubated in secondary antibody (1:10,000 anti-mouse-horseradish peroxidase in blocking solution) 1 hr at 25°C, then washed as above, and developed by using SuperSignal ULTRA substrate (Pierce). For phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C treatment, a confluent 10-cm dish of cells was switched to low serum medium (DMEM/0.5% calf serum) with or without phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C at 1 unit/ml (Oxford Glycosystems, Rosedale, NY) for 1 hr at 37°C. The medium was collected, and cells were washed and collected in SDS sample buffer. Medium and cell samples were subjected to immunoblot analysis as above. For Ret phosphorylation assays, fibroblasts were treated with recombinant GDNF at 100 ng/ml, NTN at 100 ng/ml, or PSP at 100 ng/ml for 10 min, collected, immunoprecipitated with an agarose-conjugated anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (Calbiochem), and immunoblotted (anti-Ret antibody C-19, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as described (22).

RESULTS

Identification, Sequence Analysis, and Genomic Localization of GFRα3.

The protein sequence of human GFRα2 was used as a query to the dbEST database by using the blast search algorithm (27). Of the EST sequences identified, several did not correspond identically to either GFRα1 or GFRα2 but had significant homologies to both sequences (AA049894, AA050083, AA041935, and AA238748). These clones were acquired from the Washington University EST project and sequenced. One of these corresponded to a full-length mouse cDNA that we have called GFRα3. Sequence information from the mouse cDNA was used to identify human genomic and cDNA clones, and the corresponding human and mouse predicted protein sequences are shown in Fig. 1A. The translations for both human and mouse GFRα3 indicate an ≈38.8-kDa protein with a putative N-terminal signal sequence (28), three putative N-linked glycosylation sites, and a hydrophobic stretch of residues at the C terminus consistent with a GPI direction sequence (29) like those present in the related proteins GFRα1 and GFRα2 (7, 20–22).

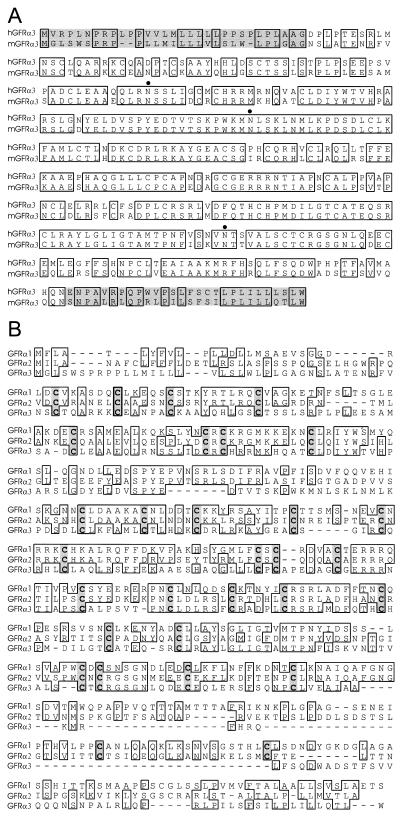

Figure 1.

Sequence analysis and alignment of GFRα3. (A) Alignment of the amino acid sequences of human and mouse GFRα3. Identical residues are boxed, the N- and C-terminal pro regions are shaded, and putative N-linked glycosylation sites are marked by dots. (B) Alignment of mouse GFRα family members. Identical residues are boxed, and shared cysteines are shaded. Note the divergence of GFRα3 sequence, particularly the large deletion in the C-terminal region.

GFRα3 is approximately 34% and 36% identical to GFRα1 and GFRα2, respectively, and is therefore more divergent from the two, which are 48% identical to each other. Alignment of the three mouse GFR proteins illustrates the highly conserved cysteine backbone and reveals a relatively large region absent from GFRα3 at the C-terminal region of the protein just before the GPI direction site and hydrophobic terminus (Fig. 1B). Homology between GFRα1 and GFRα2 is also low in this region (28% identity), and it is therefore the most variable region between the three family members.

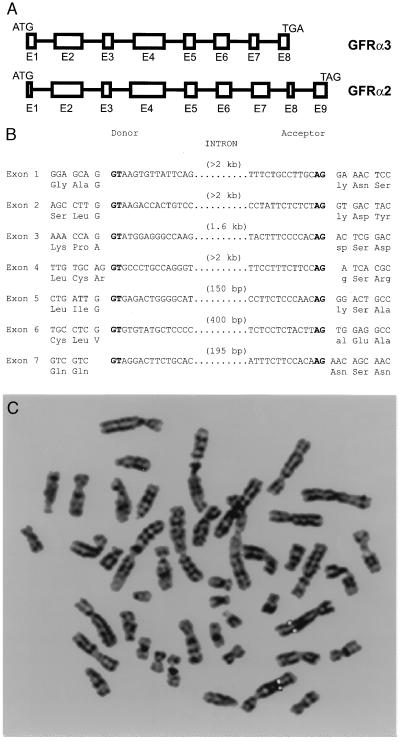

We further identified and sequenced genomic clones for both GFRα3 and GFRα2 in mouse and then identified the exon–intron boundaries within the coding region (Fig. 2). These revealed a similar gene structure and confirmed that the region absent in GFRα3 at the C terminus is not the result of alternative splicing in the cDNAs identified, because there is no putative exon or homologous sequence in intron 7 that corresponds to GFRα2 exon 8. With a human genomic clone, we performed fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis to determine the chromosomal localization of GFRα3 (Fig. 2C). Hybridization of biotin- or digoxigenin-labeled probes revealed a symmetrical fluorescent signal on 5q31.2–32. Several human disorders are associated with this region of chromosome 5 including Treacher–Collins–Franceschetti syndrome 1, diastrophic dysplasia, progressive low-frequency deafness, and hyperekplexia, an autosomal dominant neurological disorder (30). Also, recurrent balanced and unbalanced rearrangements with breakpoints involving 5q31–32 have been reported in acute lymphoblastic and lymphocytic leukemia, chronic lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative disorders, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, and adenocarcinoma of the stomach and intestine (31).

Figure 2.

Genomic analysis of GFRα3. (A) Intron–exon junctions in the coding region of GFRα2 and GFRα3. Exons are represented by boxes and scaled according to size. Introns (intervening lines) are not to scale. Note that GFRα3 entirely lacks one exon relative to GFRα2. (B) Precise intron sites in the mouse GFRα3 gene. Consensus splice sites are shown in boldface type. (C) Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of the human GFRα3 gene location. Digital image of a metaphase chromosome spread derived from methotrexate-synchronized normal human peripheral leukocytes after hybridization with a digoxigenin-labeled GFRα3 genomic probe and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole counterstaining. Both copies of chromosome 5 have symmetrical rhodamine signals on sister chromatids at region 5q 31.2–32.

Expression Analysis of GFRα3 in Developing and Adult Human Tissues.

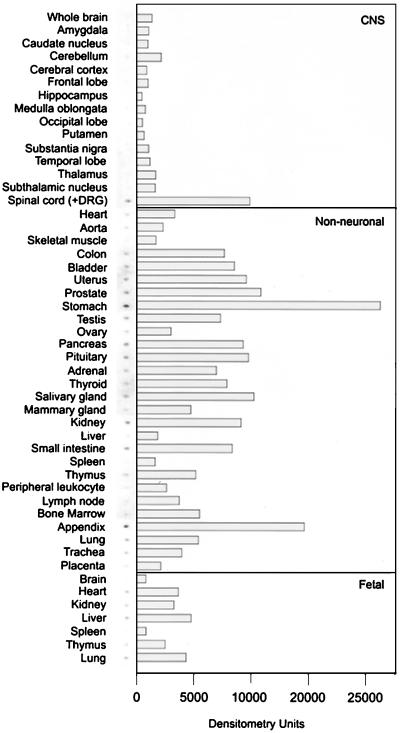

To obtain an extensive survey of tissues in which GFRα3 is expressed in the developing and adult human, we probed a human MRB array of poly(A)+ RNA from 50 tissues by using a fragment of the human GFRα3 sequence as a probe (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, in contrast to what has been observed for GFRα1 and GFRα2, essentially no expression was observed in whole brain or in any of 13 subdissected regions of the adult brain. Moderate expression of GFRα3 was observed in spinal cord; however, it is likely that this signal corresponds to DRGs that are not removed from the tissue samples before preparation of the RNA (see below).

Figure 3.

Survey of GFRα3 expression in human tissues. A human MRB (CLONTECH) was probed with a fragment of the human GFRα3 cDNA. The hybridization signals are shown next to the signal intensity quantified by using a PhosphorImager. GFRα3 was low or absent in structures of the CNS and moderate in some nonneuronal tissues, particularly those of the digestive system, urogenital system, and several glandular structures. Note that the spinal cord sample contained DRG material, which is likely the source of GFRα3 expression (see text and Fig. 4).

Expression of GFRα3 was observed in many nonneuronal tissues, particularly stomach and appendix. The digestive tract showed expression throughout (stomach, small intestine, and colon). GFRα3 expression was also observed in several tissues of the urogenital system, including the kidney. Several types of glandular tissue showed low expression, and very low or no expression was observed in tissues and cells of the hematopoetic system. A comparison with fetal tissues revealed a similar pattern to adult, with no brain expression evident and a relatively low signal observed in several nonneuronal tissues. In summary, this initial survey of fetal and adult human tissue expression revealed that in contrast to its two known family members, GFRα3 does not appear to be expressed in the fetal or adult brain but is expressed in the digestive tract and urogenital system.

Expression of GFRα3 in the Developing Mouse Embryo by in Situ Hybridization.

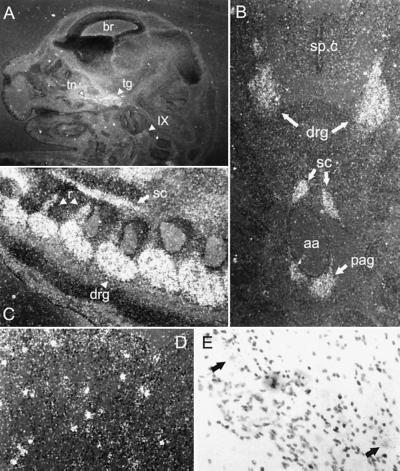

To analyze the location of GFRα3 expression within developing mouse tissues, we performed in situ hybridization analysis of embryonic day 14 (E14) mice (Fig. 4). From the human MRB data above, we expected low-level expression in several mouse tissues and no expression in brain. Indeed, no expression was observed in mouse brain at E14 in any region (Fig. 4A and data not shown). Highest expression was observed in developing peripheral nerve and ganglia. DRGs and the preaortic abdominal sympathetic ganglia (of Zuckerkandl) showed high-level expression that appeared diffusely throughout the ganglia (Fig. 4 B and C). The embryonic and adult spinal cord itself showed no staining in any region, in contrast to the results of the MRB (Fig. 4B and data not shown). As mentioned above, because DRGs are a component of the RNA preparations on the human MRB (CLONTECH), it is likely that the GFRα3 expression observed in the human spinal cord sample was because of its presence in DRGs. High-level expression was also observed in cranial ganglia, including the trigeminal and superior glossopharyngeal ganglia (Fig. 4A) and also in the sympathetic chain ganglia and stellate ganglion (Fig. 4 B and C and data not shown). Only low-level diffuse staining was observed in nonneuronal tissues at E14. Finally, peripheral nerve showed high-level expression of GFRα3, including trigeminal nerve, spinal nerve roots, and nerves of both the brachial and lumbosacral plexi (Fig. 4 A–C and data not shown). Therefore, in situ hybridization analysis of GFRα3 in the developing mouse indicates that it is highly expressed in peripheral nerve and ganglia, including sensory (DRG, trigeminal, and glossopharyngeal), and sympathetic ganglia (stellate, chain, and preaortic ganglia), and not expressed in the central nervous system.

Figure 4.

In situ hybridization analysis of GFRα3 expression in mouse. (A) Saggital section of E14 mouse head. GFRα3 is observed in trigeminal ganglion (tg) and nerve (tn) and in the glossopharyngeal ganglion (IX) but not in brain (br). (B) Transverse section of E14 mouse showing GFRα3 expression in DRG but not in the spinal cord (sp.c). Around the abdominal aorta (aa), staining is observed in the sympathetic chain ganglia (sc) and the preaortic ganglia of Zuckerkandl (pag). (C) Saggital section of E14 mouse spinal column showing DRGs (drg), sympathetic chain (sc), and labeled nerve roots (r). (D) Dark-field photomicrograph of adult trigeminal ganglion showing punctate staining in contrast to the diffuse staining observed at E14. (E) Bright-field photomicrograph of adult trigeminal ganglion at higher power, showing GFRα3 is localized to neurons (arrows).

Expression of GFRα3 at E14 was diffuse in all of these ganglia and was present in peripheral nerve, much like the expression of both GFRα1 and GFRα2 (22), suggesting that GFRα3 is expressed in Schwann cells in nerve and ganglia in the absence of Ret. However, examination of the adult trigeminal nucleus and DRGs revealed punctate cellular staining that is clearly in a subpopulation of neurons when examined with bright-field microscopy (Fig. 4 D and E and data not shown). Furthermore, GFRα3 was undetectable in adult trigeminal nerve by in situ hybridization (data not shown). Therefore, as demonstrated in the trigeminal system, initial diffuse GFRα3 expression during development that is both neuronal and nonneuronal becomes restricted to neuronal expression in adulthood.

Functional Analysis of GFRα3 as a Component of GF Signaling in Vitro.

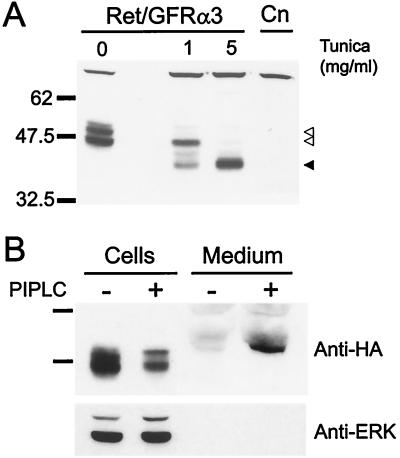

Because the two closely related proteins GFRα1 and GFRα2 are GPI-linked proteins that can both mediate GDNF or NTN signaling through Ret (22, 23), we analyzed the properties of the GFRα3 protein and its ability to function as a GPI-linked component of a GDNF, NTN, or PSP receptor with Ret. Fibroblasts were generated that stably express both Ret and an HA-tagged form of GFRα3 (NHA-GFRα3) to assess the production of GFRα3 protein. Immunoblot analysis of NHA-GFRα3-containing cells with an anti-HA antibody revealed a doublet at approximately 47 and 51 kDa that was not observed in the control parental line (Fig. 5A). Because both species migrated more slowly than the analogous protein generated in vitro (data not shown), we examined whether GFRα3 was glycosylated at any of the putative N-linked glycosylation sites present in the sequence (see Fig. 1A). Tunicamycin treatment of the cells, which blocks N-linked glycosylation, depleted both forms of the protein, and at high levels of tunicamycin, only a single band was observed at ≈39 kDa, the predicted molecular mass of GFRα3. Treatment of NHA-GFRα3-containing cells with the enzyme phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C, which specifically cleaves GPI-linked proteins from the cell surface, depleted the level of NHA-GFRα3 from the cells and induced the presence of a similarly sized band in the cell medium (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that GFRα3 is a multiply N-glycosylated protein that is GPI-linked to the cell surface like the related proteins GFRα1 and GFRα2.

Figure 5.

Analysis of NHA-GFRα3 protein in transfected fibroblasts. (A) Anti-HA immunoblot of fibroblasts stably transfected with HA-tagged GFRα3 and Ret (Ret/GFRα3) show a doublet at approximately 47 and 51 kDa (open arrowheads) that was not present in the parental line (Cn). Tunicamycin (Tunica) treatment of the cells for 24 hr to block N-linked glycosylation resulted in loss of the upper band at 1 mg/ml, and appearance of a lower molecular mass band. At a tunicamycin concentration of 5 mg/ml, only the lower band running at the predicted molecular mass for GFRα3 was visible (solid arrowhead). (B) Phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PIPLC) treatment of NHA-GFRα3 expressing fibroblasts to specifically cleave GPI-linked proteins resulted in depletion of the NHA-GFRα3 from the cells and induced the presence of a band in the medium corresponding to NHA-GFRα3. Reprobing of the blot with an anti-ERK p42/44 antibody is shown below to indicate equal loading of cell lysates.

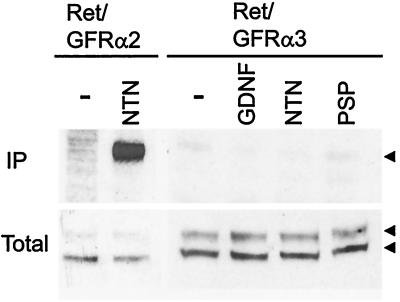

GDNF and NTN can signal through the Ret receptor tyrosine kinase and are capable of using both either GFRα1 or GFRα2 as a coreceptor (22). Recently, it was shown that PSP does not use either of these receptor complexes (3) and likely uses a different receptor complex. Therefore, we investigated whether stimulation of fibroblasts expressing both GFRα3 and Ret with any of the three GF ligands induced activation of the Ret receptor tyrosine kinase. Although stimulation of Ret/GFRα2-containing fibroblasts with NTN induced strong Ret phosphorylation as expected, fibroblasts that express Ret and NHA-GFRα3 did not respond via Ret phosphorylation to stimulation with any of the three known GF ligands (Fig. 6). Fibroblasts expressing a non-HA-tagged form of GFRα3 and Ret also did not respond to ligand stimulation (data not shown). Therefore, although GFRα3 is similar in structure to GFRα1 and GFRα2, it does not form a signaling receptor complex with Ret for any of the known ligands and may therefore have an as yet unknown ligand or require the presence of additional proteins to take part in GF signaling.

Figure 6.

Functional analysis of the fibroblasts expressing Ret and GFRα3. Fibroblasts that stably express Ret and GFRα2 (Ret/GFRα2) or Ret and NHA-GFRα3 (Ret/GFRα3) were left untreated (−) or stimulated with the indicated GF ligand (100 ng/ml) for 10 min, immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies, separated by SDS/PAGE, and immunoblotted with an anti-Ret antibody. Fractions of the total lysates before immunoprecipitation are shown below to demonstrate presence of Ret (arrowheads) and equal loading (Total). As expected, stimulation of Ret/GFRα2 containing fibroblasts with NTN shows strong Ret phosphorylation, whereas stimulation of Ret/GFRα3-containing fibroblasts with GDNF, NTN, or PSP did not lead to Ret phosphorylation, indicating GFRα3 is not able to form a functional receptor with Ret for any of these GF ligands.

DISCUSSION

Herein we reported the identification and initial characterization of GFRα3, the third member of the GF receptor family. As predicted by the sequence, GFRα3 is GPI-linked to the cell surface like its relatives GFRα1 and GFRα2. However, the protein sequence of GFRα3 is the most divergent of the GFR family and is missing a relatively large C-terminal region that contains two conserved cysteines in GFRα1 and GFRα2. Analysis of the GFRα3 gene structure excludes the possibility that this deletion is the result of alternative splicing and, therefore, GFRα3 is entirely missing one exon relative to GFRα1 and GFRα2. This divergence in the structure of GFRα3 suggests a more divergent function, which is supported by its inability to function as a receptor for any of the known GF ligands with Ret.

Expression analysis of GFRα3 also indicates a divergence from the other members of the GFR family, namely, the lack of expression observed in CNS structures. GFRα1 and GFRα2 are both highly expressed in several CNS structures including embryonic motor neurons and dopaminergic midbrain neurons and likely mediate the effects of GDNF and NTN on these neuronal populations (7, 21, 22). GFRα3 is expressed highly in developing peripheral and cranial ganglia, including DRGs and trigeminal neurons, which express Ret and are responsive to GDNF and NTN (2, 13–15). Although we did not observe any GFRα3 involvement in GF ligand signaling through Ret, GFRα3 may play a more subtle modulatory role in GF signaling in peripheral ganglia that was not apparent in our analysis. Lastly, the inverse relationship of sites of GFRα3 expression (PNS only) and sites of PSP action (CNS only) strongly suggests that GFRα3 is not involved in PSP signaling.

With the demonstration that GFRα3 is expressed in developing peripheral nerve, all three GFRαs are developmentally expressed in the supportive cells of nerve and ganglia in the absence of Ret (21, 22, 26). Because both peripheral neurons and Schwann cells arise from neural crest precursors, the induction of Ret in a subset of coreceptor expressing neural crest precursors may yield responsiveness to GF ligands that can then function in lineage determination or as neuronal survival and/or maturation factors. The expression of GFRαs in nonneuronal cells during embryogenesis may be important in the development of peripheral nerve and ganglia or may be vestigial. However, the increased expression of GFRα1 after nerve injury indicates it plays a functional role in nerve regeneration and suggests a similar role may occur during development (22, 26).

Our analysis of transfected fibroblasts indicates that GFRα3 does not form a functional receptor complex with Ret for any of the known GF ligands. There are several possibilities to explain this result, all of which suggest the presence of additional receptor system components. We cannot exclude the possibility that known GF ligands interact with GFRα3 in the presence of another Ret-like signaling protein. The existence of another Ret-like signaling molecule has also been proposed to explain the expression of GFRα1 and GFRα2 in several structures without Ret (refs. 22 and 26; J.P.G., R.H.B., P. Kotzbauer, P. Lampe, P. Osborne, J.M., and E.M.J., unpublished work). Alternatively, GFRα3 may mediate Ret signaling for an as yet unknown ligand of the GDNF family. Finally, the lack of PSP interaction with any known receptor complex suggests either an additional coreceptor or signaling component is required to mediate PSP signaling. We have analyzed neuroblastoma cell lines that express all three coreceptor proteins and Ret but do not respond to PSP, indicating that combinations of known signaling components are also not sufficient for PSP signaling (M.G.T. and R.H.B., unpublished data). Furthermore, PSP does not support neuronal survival in the DRGs and superior cervical ganglia where GFRα3 is expressed (3), providing further evidence that PSP does not interact with GFRα3, even in biological systems where additional GFRα3-associating signaling proteins are likely present.

In summary, we have reported the identification and initial characterization of GFRα3. Functional and expression analyses of all known components of the GDNF ligand and receptor families suggest that additional members of both the ligand and receptor families are likely to exist.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Fahrner, K. Simburger, and S. Audrain for their outstanding technical support and R. O. Heuckeroth for critical analysis of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AG13729 and R01 AG13730 and Genentech. Washington University, E.M.J., and J.M. may receive income based on a license to Genentech.

ABBREVIATIONS

- GDNF

glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- NTN

neurturin: PSP, persephin

- GF

GDNF family

- GFRα

GDNF family receptor α component

- GPI

glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol

- CNS

central nervous system

- PNS

peripheral nervous system

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- EST

expressed sequence tag

- HA

hemagglutinin

- MRB

master RNA blot

- E

embryonic day(s)

Footnotes

References

- 1.Lin L-F H, Doherty D H, Lile J D, Bektesh S, Collins F. Science. 1993;260:1130–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.8493557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotzbauer P T, Lampe P A, Heuckeroth R O, Golden J P, Creedon D J, Johnson E M, Milbrandt J D. Nature (London) 1996;384:467–470. doi: 10.1038/384467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milbrandt J, de Sauvage F, Fahrner T J, Baloh R H, Leitner M L, Tansey M G, Lampe P A, Heuckeroth R O, Kotzbauer P T, Simburger K S, et al. Neuron. 1998;20:245–253. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stromberg I, Bjorklund L, Johansson M, Tomac A, Collins F, Olson L, Hoffer B, Humpel C. Exp Neurol. 1993;124:401–412. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudson J, Granholm A-C, Gerhardt G A, Henry M A, Hoffman A, Biddle P, Leela N S, Mackerlova L, Lile J D, Collins F, Hoffer B J. Brain Res Bull. 1995;36:425–432. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)00224-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomac A, Lindqvist E, Lin L-F H, Ogren S O, Young D, Hoffer B J, Olson L. Nature (London) 1995;373:335–339. doi: 10.1038/373335a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein R D, Sherman D, Ho W H, Stone D, Bennett G l, Moffat B, Vandlen R, Simmons L, Gu Q, Hongo J A, et al. Nature (London) 1997;387:717–721. doi: 10.1038/42722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson C E, Phillips H S, Pollock R A, Davies A M, Lemeulle C, Armanini M, Simpson L C, Moffat B, Vandlen R A, Koliatsos V E, Rosenthal A. Science. 1994;266:1062–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.7973664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zurn A D, Baetge E E, Hammang J P, Tan S A, Aebischer P. NeuroReport. 1994;6:113–118. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199412300-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oppenheim R W, Houenou L J, Johnson J E, Lin L-F H, Li L, Lo A C, Newsome A L, Prevette D M, Wang S. Nature (London) 1995;373:344–346. doi: 10.1038/373344a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mount H T J, Dean D O, Alberch J, Dreyfus C F, Black I B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9092–9096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arenas E, Trupp M, Akerud P, Ibanez C. Neuron. 1995;15:1465–1473. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buj-Bello A, Buchman V L, Horton A, Rosenthal A, Davies A M. Neuron. 1995;15:821–828. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebendal T, Tomac A, Hoffer B J, Olson L. J Neurosci Res. 1995;40:276–284. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490400217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trupp M, Ryden M, Jornvall H, Funakoshi H, Timmusk T, Arenas E, Ibanez C F. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:137–148. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.1.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vega Q, Worby C, Lechner M, Dixon J, Dressler G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10657–10661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sainio K, Suvanto P, Saarma M, Arumae U, Lindahl M, Davies J A, Sariola H. Development. U.K.: Cambridge; 1997. 124, 4077–4087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trupp M, Arenas E, Fainzilber M, Nilsson A-S, Sieber B-A, Grigoriou M, Kilkenny C, Salazar-Grueso E, Pachnis V, Arumae U, et al. Nature (London) 1996;381:785–789. doi: 10.1038/381785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creedon D J, Tansey M G, Baloh R H, Osborne P A, Lampe P A, Fahrner T J, Heuckeroth R O, Milbrandt J, Johnson E M J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7018–7023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.7018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jing S, Wen D, Yu Y, Holst P L, Luo Y, Fang M, Tamir R, Antonio L, Hu Z, Cupples R, et al. Cell. 1996;85:1113–1124. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Treanor J J S, Goodman L, Sauvage F, Stone D M, Poulsen K T, Beck C D, Gray C, Armanini M P, Pollock R A, Hefti F, et al. Nature (London) 1996;382:80–83. doi: 10.1038/382080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baloh R H, Tansey M G, Golden J P, Creedon D J, Heuckeroth R O, Keck C L, Zimonjic D B, Popescu N C, Johnson E M J, Milbrandt J. Neuron. 1997;18:793–802. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanicola M, Hession C, Worley D, Carmillo P, Ehrenfels C, Walus L, Robinson S, Jaworski G, Wei H, Tizard R, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6238–6243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brewer C B. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;43:233–245. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorodinsky A, Zimonjic D B, Popescu N C, Milbrandt J. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1997;78:289–290. doi: 10.1159/000134674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trupp M, Belluardo N, Funakoshi H, Ibanez C. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3554–3567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03554.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen H, Jacob E, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Udenfriend S, Kodukula K. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:563–591. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKusick V A, Amberger J S. J Med Genet. 1993;30:1–26. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitelman F, Mertens F, Johansson B. Nat Genet Suppl. 1997;15:417–474. doi: 10.1038/ng0497supp-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]