Abstract

Background

Anthocyanins are flavonoid pigments that are responsible for purple coloration in the stems and leaves of a variety of plant species. Anthocyaninless (anl) mutants of Brassica rapa fail to produce anthocyanin pigments. In rapid-cycling Brassica rapa, also known as Wisconsin Fast Plants, the anthocyaninless trait, also called non-purple stem, is widely used as a model recessive trait for teaching genetics. Although anthocyanin genes have been mapped in other plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana, the anl locus has not been mapped in any Brassica species.

Results

We tested primer pairs known to amplify microsatellites in Brassicas and identified 37 that amplified a product in rapid-cycling Brassica rapa. We then developed three-generation pedigrees to assess linkage between the microsatellite markers and anl. 22 of the markers that we tested were polymorphic in our crosses. Based on 177 F2 offspring, we identified three markers linked to anl with LOD scores ≥ 5.0, forming a linkage group spanning 46.9 cM. Because one of these markers has been assigned to a known B. rapa linkage group, we can now assign the anl locus to B. rapa linkage group R9.

Conclusion

This study is the first to identify the chromosomal location of an anthocyanin pigment gene among the Brassicas. It also connects a classical mutant frequently used in genetics education with molecular markers and a known chromosomal location.

Background

Anthocyanins are flavonoid pigments that are responsible for purple coloration in the stems and leaves of a variety of plant species. They have been cited as contributing to protection from photoinhibition [1], protection from UVB light [2] and modification of captured light quality and quantity [3]. Additionally, anthocyanins may be involved in metal accumulation. For example, Brassica anthocyaninless mutants show decreased tungsten accumulation [4] and fail to produce a water-soluble blue compound, likely a molybdenum-anthocyanin complex, in peripheral cell layers upon addition of molybdenum [5].

Anthocyanin-related genes have been isolated in diverse species. AN1 and AN2 encode transcription factors that regulate pigment production in petunia [6]. Pp1, Pp2 and Pp3 contribute to purple pigment in bread wheat [7]. Anthocyanin accumulation in pepper flowers is attributed to gene A, orthologs of which have been mapped in the related Solanaceae species tomato and potato [8]. In the model organism Arabidopsis thaliana, study of anthocyaninless mutants led to the discovery of ANTHOCYANINLESS1 (TAIR locus ANL1), responsible for anthocyanin production; ANTHOCYANINLESS2 (ANL2), a homeobox gene that affects anthocyanin distribution [9]; ANTHOCYANIN11 (TAIR locus AT1G12910), which contributes to anthocyanin production; TRANSPARENT TESTA 9 (TAIR locus TT9), which is involved in flavonoid biosynthesis, and three other pigmentation genes (TAIR loci AT1G56650, AT5G13930, and LAB).

Anthocyaninless mutants of rapid-cycling Brassica rapa (RBr), also known as Wisconsin Fast Plants, completely lack the purple coloration. (Wisconsin Fast Plants is a trademarked name, so we shall refer to them as RBr.) RBr are strains of Brassica bred for short life cycle, early flowering, and ease of cultivation, and are used in science education and research [10]. Absence of anthocyanin pigment in RBr is a recessive trait controlled by the anthocyaninless (anl) locus. The anthocyaninless trait, also called non-purple stem, makes an excellent model trait in monohybrid crosses in genetics education because the trait is easily scored and expressed at all stages of the life cycle [11]. In addition to its use in education, the B. rapa anthocyaninless phenotype has also been used as a marker to assess honey bee pollen deposition patterns [12] and to evaluate gene flow from transgenic plants into wild relatives [13].

RBr are a valuable tool for "hands on" genetics teaching. Cultivation is simple and inexpensive, and genetic crosses are easy to perform because they are self-incompatible for pollination. Many easily scored Mendelian traits have been identified including anthocyaninless, yellow-green (yellow-green coloration of all leaves), and hairless (lack of trichome on stems and leaves), to name a few. In addition to Mendelian traits, quantitative and polygenic traits are also available. For example, in those plants that possesses a wild type ANL allele, the intensity of anthocyanin coloration is a quantitative trait described as purple anthocyanin (0–9) (Pan(0–9)), which is controlled by multiple modifying alleles [14,15]. Likewise, the trichome density, or "hairiness," is a quantitative trait affected by polygenic variation.

Despite these strengths, the RBr genetic repertoire lacks some important elements. All of the reported RBr mutations have been found to segregate independently of each other, so linkage analysis cannot be done with RBr. Also, none of the RBr loci used for education have been characterized at the molecular level. Therefore, we have sought to add such capabilities to RBr genetics, and our first step is to map the anl locus using molecular markers.

Although anthocyanin mutants are studied in Brassica and have been mapped in the related Arabidopsis, the anl locus has not been mapped in any Brassica species. In this study we create a microsatellite marker-based linkage map of anl in RBr. The linkage group may be integrated into known B. rapa linkage groups and used for comparative mapping among related species. Our findings open the door for experiments in linkage analysis and the use of molecular markers with RBr in science education.

Results

Microsatellite markers

We tested a total of 138 microsatellite markers for amplification and polymorphism in the RBr test population. Most (122 out of 138) were from B. rapa, but a few from other Brassica species were tested since the sequence homology between Brassicas in the U Triangle allowed for analysis of microsatellites first identified in B. napus, B. oleracea and B. nigra [16-18]. Of the 138 primer pairs tested, 37 amplified a product under our PCR conditions. Of these, 22 were polymorphic in our crosses (Table 1). We further tested these polymorphic microsatellites for linkage to anl.

Table 1.

Microsatellite markers found to be polymorphic in RBr

| Microsatellite | Na | Allelesb | Allele size (bp)c |

| Bn9A | 31 | 2 | 200–205 |

| BRMS-006 | 26 | 3 | 120–225 |

| BRMS-024 (b) | 72 | 3 | 170–200 |

| BRMS-033 | 69 | 2 | 240–350 |

| BRMS-034 | 47 | 3 | 150–180 |

| BRMS-037 | 24 | 2 | 150–200 |

| BRMS-040 | 89 | 2 | 195–270 |

| BRMS-042-2 | 69 | 3 | 220–240 |

| BRMS-050 | 73 | 2 | 170–190 |

| CAL-SSRLS-107 | 52 | 3 | 140–165 |

| Na10-G10 | 14 | 2 | 135–220 |

| Na12-H09 | 44 | 3 | 130–215 |

| Ra2-A01 | 55 | 3 | 95–120 |

| Ra2-D04 | 38 | 2 | 160–170 |

| Ra2-E04 | 24 | 3 | 110–120 |

| Ra2-E07 | 48 | 4 | 90–185 |

| Ra2-G04 | 43 | 3 | 180–195 |

| Ra2-G05 | 56 | 3 | 130–175 |

| Ra2-G09 | 14 | 2 | 235–245 |

| Ra2-D02B | 14 | 2 | 275–290 |

| Ra3-H09 | 24 | 2 | 110–120 |

| Ra3-H10 | 50 | 2 | 140–185 |

aNumber of informative F2 plants used to test linkage.

bNumber of alleles observed among the 177 anl plants constituting the RBr F2 test population.

cApproximate allele sizes based on visual comparison to 100-bp ladder on non-denaturing polyacrylamide minigels.

F2 test population

We employed an inbred sib-pair design for genetic mapping, and chose plants for genotyping that would maximize the marker information obtained. Because rapid-cycling Brassica rapa strains are outbred, when a cross is conducted between two different strains, a given marker may be polymorphic between some pairs of parental generation plants but not others. Even for markers that are polymorphic between strains, some alleles may be shared. Therefore, after we had identified microsatellite markers that were polymorphic in the Standard Brassica rapa strain (Table 1), we tested them for polymorphism in each of the parental generation mating pairs. From these, we chose six mating pairs that displayed polymorphism for at least one marker. F1 generation plants were grown and siblings were mated (inbred sib-pairs). The F1 sib-pairs were surveyed, and those exhibiting a high degree of marker heterozygosity were chosen for further analysis. These 44 F1 plants (22 F1 sib-pairs) produced 699 F2 plants, of which 177 (25.32%) were anthocyaninless. This ratio is consistent with monogenic inheritance of this recessive trait. The 177 anthocyaninless F2 plants constituted the RBr test population for determining linkage between anl and the 22 polymorphic microsatellites (Table 1). The use of the inbred sib-pair design allowed us to clearly distinguish whether microsatellite bands detected in the F2 generation were identical by descent or identical by state.

Linkage analysis and map construction

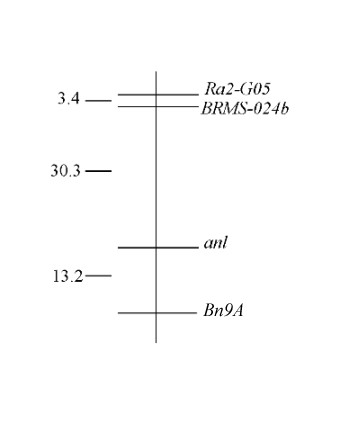

After we identified markers that were polymorphic in the parental generation, we evaluated each as a candidate for linkage to the anl locus, followed by more detailed linkage analysis of candidates. All primer pairs used for mapping produced bands that segregated from each other as alleles, thus verifying that the microsatellites are single locus markers. We identified the linkage phase between anl and each marker in the F1 generation of each family and then classified anthocyaninless F2 progeny as either parental or recombinant. Three microsatellite markers were candidates for linkage to anl due to significant deviation from a 1:1 ratio of parental to recombinant genotypes. Through two-point LOD score analysis between anl and the candidate markers, we found that each presented a LOD score ≥ 4.6 at distances less than 34 cM from anl. Finally, we used multi-point LOD score analysis with Mapmanager QTX [19] to assemble a linkage group containing markers Bn9A, BRMS-024b and Ra2-G05 and the anl locus, all with LOD scores ≥ 5.0 (Table 2). In this linkage group (Figure 1), at least one marker is present on each side of anl. The discovery of microsatellite markers flanking anl is important in integrating this anl linkage group into known RBr linkage groups, and for comparative mapping studies.

Table 2.

LOD scores and map distances for microsatellite loci linked to anl in RBr

| Locus | Distance from anl (cM)a | LOD Scorea |

| Bn9A | 13.2 | 8.3 |

| BRMS-024b | 30.3 | 6.8 |

| Ra2-G05 | 33.7 | 5.0 |

aDistances are based on the Kosambi map function using multi-point LOD analysis in Mapmanager QTX (p < 0.05) [19, 27]

Figure 1.

Linkage map of the anl locus in RBr. Map distances (cM) and locus order were evaluated using the Kosambi map function of Mapmanager QTX (p < 0.05, LOD ≥ 5.0) [19, 27].

We also tested all markers for pairwise linkage between markers, but did not find any linkage between those markers not linked to anl.

Discussion

The genetic linkage of anl and Bn9A allows us to determine the chromosomal location of the anthocyaninless gene. Bn9A has been mapped to a region near the center of B. rapa linkage group R9 [20] (previously referred to as LG3 [21,22]). Thus, it can be inferred that both anl and the previously unmapped Ra2-G05 are also located on R9.

Our data strongly indicate that a polymorphic microsatellite that is amplified with primers for BRMS-024 [23] is part of the anl linkage group (Table 2) which we have shown to be a part of Brassica rapa linkage group R9 by virtue of its member Bn9A. However, BRMS-024 has been found by others to belong to linkage group R1 (G. Teakle, personal communication). Given such results, it is likely that sequences that can be amplified with BRMS-024 primers are present more than once in the B. rapa genome due to extensive intragenomic duplications [24]. Therefore, we refer to the locus that we have mapped as BRMS-024b.

Comparative mapping studies allow utilization of B. rapa map data in other crucifers. B. rapa and Arabidopsis thaliana are related by a common ancestor from which they differentiated ~14.5 to 20.4 million years ago [25]. Although markers may be twice as far apart in the larger B. rapa genome [22], the two species possess many regions with conserved organization; segments as large as 282.5 cM from the B. rapa map are observed in Arabidopsis [26]. A multinational effort to sequence the genomes of Brassica species is currently under way (Multinational Brassica Genome Project, 2007, http://www.brassica.info), including the sequencing of B. rapa linkage group R9 (Korean Brassica Genome Project, 2006, http://www.brassica-rapa.org). Linkage group R9, tentatively referred to as chromosome 5 [26], is now identified as cytogenetic Chr1 for use in comparative studies with the Arabidopsis chromosomal map [20]. The Bn9A locus on B. rapa Chr1 is located within a region that is conserved on Arabidopsis Chr1 (Korean Brassica Genome Project, 2006, http://www.brassica-rapa.org). Additionally, a small region just below the Bn9A locus in B. rapa is collinear with another region on Arabidopsis Chr1 (Korean Brassica Genome Project, 2006, http://www.brassica-rapa.org). While we cannot yet be certain that anl lies precisely within these conserved boundaries on B. rapa Chr1, the presence of the orthologous anthocyanin pigment gene AN11 on Arabidopsis Chr1 (TAIR accession number 2010356) supports the idea that the Arabidopsis ortholog of anl is located within the conserved regions.

Conclusion

We have found the chromosomal location of the anl locus in RBr and identified three molecular markers linked to it. This linkage map of anl in B. rapa represents the first localization of an anthocyanin pigment gene in the Brassicas, and may be used for B. rapa map enhancement and comparative mapping of related species.

Methods

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

138 Brassica microsatellites and their PCR primer sequences were identified from published sources and primer pairs were produced by custom synthesis (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) (Table 3). Nucleotide sequences of primers were obtained from the Brassica microsatellite information exchange of the Multinational Brassica Genome Project web site http://www.brassica.info/ssr/SSRinfo.htm. All primer pairs were tested for ability to amplify a product from rapid-cycling Brassica rapa DNA under a standard set of PCR conditions. PCR reactions were carried out as follows: 1X Accuprime II buffer (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 uM dNTPs, 0.05 U/uL Accuprime Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen), 40 ng Brassica rapa DNA, 10 pmol forward primer and 10 pmol reverse primer in a total reaction volume of 10 uL. The PCR program was as follows: 94°C for 2 minutes; 24 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds; 61°C for 1 minute; 72°C for 1 minute; finished at 72°C for 4 minutes.

Table 3.

Primer nucleotide sequences of polymorphic microsatellite markers in RBr

| Microsatellite | Reference | Primer sequencesa |

| Bn9A | [28] | GAGCCATCCCTAGCAAACAAG CGTGGAAGCAAGTGAGATGAT |

| BRMS-006 | [23] | TGGTGGCTTGAGATTAGTTC ACTCGAAGCCTAATGAAAAG |

| BRMS-024 | [23] | TGAATTGAAAGGCATAAGCA CAGCCTCCACCACTTATTCT |

| BRMS-033 | [23] | GCGGAAACGAACACTCCTCCCATGT CCTCCTTGTGCTTTCCCTGGAGACG |

| BRMS-034 | [23] | GATCAAATAACGAACGGAGAGA GAGCCAAGAAAGGACCTAAGAT |

| BRMS-037 | [23] | CTGCTCGCATTTTTTATCATAC TACGCTTGGGAGAGAAAACTAT |

| BRMS-040 | [23] | TCGGATTTGCATGTTCCTGACT CCGATACACAACCAGCCAACTC |

| BRMS-042-2 | [23] | AGCTCCCGACAGCAACAAAAGA TTCGCTTCCTTTTCTGGGAATG |

| BRMS-050 | [23] | AACTTTGCTTCCACTGATTTTT TTGCTTAACGCTAAATCCATAT |

| CAL-SSRLS-107 | [29] | GTTAAGTGTGGCGTTAGAGG CCTTGGTACATGCCACTGAA |

| Na10-G10 | [30] | TGGAAACATTGGTGTTAAGGC CATAGATTCCATCTCAAATCCG |

| Na12-H09 | [30] | AGGCGTCTATCTCGAAATGC CGTTTTTCAGAATCTCGTTGC |

| Ra2-A01 | [30] | TTCAAAGGATAAGGGCATCG TCTTCTTCTTTTGTTGTCTTCCG |

| Ra2-D04 | [30] | TGGATTCTCTTTACACACGCC CAAACCAAAATGTGTGAAGCC |

| Ra2-E04 | [30] | ACACACAACAAACAGCTCGC AACATCAAACCTCTCGACGG |

| Ra2-E07 | [30] | ATTGCTGAGATTGGCTCAGG CCTACACTTGCGATCTTCACC |

| Ra2-G04 | [30] | AAAACGACGTCATATTGGGC CGCTTCTTCTTCTCAGTCTCG |

| Ra2-G05 | [30] | GCCAACTTAATTGATGGGGTC CCTCAATGTTCTCTCTCTCTCTCTC |

| Ra2-G09 | [30] | ACAGCAAGGATGTGTTGACG GATGAGCCTCTGGTTCAAGC |

| Ra2-D02B | [30] | CACAGGAAACCGTGGCTAGA AACCCAACCTCAACGTCTTG |

| Ra3-H09 | [30] | GTGGTAACGACGGTCCATTC ACCACGACGAAGACTCATCC |

| Ra3-H10 | [30] | TAATCGCGATCTGGATTCAC ATCAGAACAGCGACGAGGTC |

Nucleotide sequences of primers were from [31].

DNA purification and quantitation

DNA was purified from frozen leaf tissue using Plant DNAzol Reagent (Invitrogen) with the manufacturer's recommended protocol, including the use of polyvinylpyrrolidone to remove polyphenolics. The concentration of DNA samples was assayed using Quant-iT PicoGreen Reagent (Invitrogen).

Gel electrophoresis for genotyping

Microsatellite alleles were resolved by non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Most PCR products were resolved using minigels (Mini-Protean III (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA)) consisting of 8% acrylamide/bis (24:1) run at 150 V for 60 to 90 minutes. When marker alleles could not be resolved on minigels, they were resolved in large (18 cm) gels (Protean II (Bio-Rad Laboratories)) which consisted of 8% acrylamide/bis (19:1) run at 150 V for 1350 Volt-hours. Gels were stained with SYBR Green Stain (Invitrogen) and visualized with a Molecular Dynamics Storm 860 Scanner (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

Genetic crosses and data analysis

Three-generation pedigrees were used to assess linkage between the anl locus and microsatellite markers. The rapid-cycling Brassica rapa for the parental generation were strains of Wisconsin Fast Plants obtained from Carolina Biological Supply Company (Burlington, North Carolina). The parental generation consisted of a true breeding anthocyaninless strain ("Non-Purple Stem, Hairless," catalog number 15-8812) and a true-breeding purple strain ("Standard Brassica rapa," catalog number 15-8804). One anthocyaninless and one purple plant constituted a mating pair. F1 sibling pairs were then crossed to produce the F2 generation.

Before genotyping families, microsatellite markers were screened for usefulness by testing each pair of primers for the ability to amplify a product and identify polymorphism in DNA of a panel of several Standard Brassica rapa plants. Each mating pair in the parental generation was then tested for polymorphism for those markers. When a given marker was found to be polymorphic in a pair of parental generation plants, their F1 progeny were genotyped for that marker. Finally, for each pair of mated F1 siblings in which a given marker was polymorphic and informative, their F2 generation offspring with anthocyaninless phenotype were genotyped for that marker. This inbred sib-pair mating design ensured that alleles from the F2 anthocyaninless test population could be traced to their parental generation ancestor, so that linkage phase of the marker and anl loci would be known.

For each marker that was polymorphic within a family, anthocyaninless F2 offspring were assigned a parental or recombinant designation for segregation between anl and the marker. The parental:recombinant ratio was then assessed for deviation from the expected 1:1 ratio for unlinked loci by the chi-square test. Markers presenting significant chi-square values (p < 0.05) were identified as candidates for linkage to anl, and two-point LOD analysis was performed between the marker and anl. Those markers with preliminary LOD scores greater than 3.0 were further analyzed with Mapmanager QTX (Kosambi map function, p < 0.05) to determine marker arrangements and multi-point LOD scores [19,27].

Competing interests

The author(s) declares that there are no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CB participated in the design of the study, carried out all breeding and genotyping, conducted analysis of the data, and drafted the manuscript. DW participated in the conception of the project and design of the study, assisted with analysis of the data, and edited the manuscript.

Both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation Division of Undergraduate Education grant # 0340910 (USA). The authors are extremely grateful to G. Teakle for advice on data interpretation and for sharing data on the mapping of BRMS-024 prior to publication.

Contributor Information

Carrie Burdzinski, Email: ceburdz2@oakland.edu.

Douglas L Wendell, Email: wendell@oakland.edu.

References

- Dodd IC, Critchley C, Woodall GS, Stewart GR. Photoinhibition in different colored juvenile leaves of Syzgium species. Exp Bot. 1998;49:1437–1445. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/49.325.1437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klaper R, Frankel S, Berenbaum MR. Anthocyanin content and UVB sensitivity in Brassica rapa. Photochem Photobio. 1996;63:811–813. [Google Scholar]

- Barker DH, Seaton GGR, Robinson SA. Internal and external photoprotection in developing leaves of the CAM plant Cotyledon orbiculata. Plant Cell Environ. 1996;20:617–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1997.00078.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hale KL, Tufari HA, Pickering IJ, George GN, Terry N, Pilon M, Pilon-Smits EAH. Anthocyanins facilitate tungsten accumulation in Brassica. Physiologia Plantarum. 2002;116:351–358. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1160310.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hale KL, McGrath SP, Lombi E, Stack SM, Terry N, Pickering IJ, George GN, Pilon-Smits EAH. Molybdenum sequestration in Brassica species. A role for anthocyanins? Plant Physiology. 2001;126:351–358. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.4.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mol JNM, Jenkins GI, Schafer E, Weiss D. Signal perception, transduction and gene expression involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1996;15:525–527. doi: 10.1080/713608141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrovolskaya O, Arbuzova VS, Lohwasser U, Röder MS, Bömer A. Microsatellite mapping of complementary genes for purple grain colour in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Euphytica. 2006;150:355–364. doi: 10.1007/s10681-006-9122-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaim AB, Borovsky Y, DeJong W, Paran I. Linkage of the A locus for the presence of anthocyanin and fs10.1, a major fruit-shape QTL in pepper. Theor Appl Genet. 2003;106:889–894. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo H, Peeters AJM, Aarts MGM, Pereira A, Koornneef M. ANTHOCYANINLESS2, a homeobox gene affecting anthocyanin distribution and root development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1217–1226. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.7.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams PH, Hill CB. Rapid-cycling populations of Brassica. Science. 1986;232:1385–1389. doi: 10.1126/science.232.4756.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fast Plants Monohybrid Cross. http://www.fastplants.org

- Morris WF, Mangel M, Adler FR. Mechanisms of pollen deposition by insect pollinators. Evol Ecol. 1995;9:304–317. doi: 10.1007/BF01237776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manasse R. Ecological risks of transgenic plants: effects of spatial dispersion on gene flow. Ecol Appl. 1992;2:421–438. doi: 10.2307/1941878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman IL. Teaching recurrent selection in the classroom with Wisconsin Fastplants. HortTechnology. 1999;9:579–584. [Google Scholar]

- The Rapid Cycling Brassica rapa Collection Catalog. http://www.fastplants.org/activities.research.php#menu

- Plieske J, Struss D. Microsatellite markers for genome analysis in Brassica. I. Development in Brassica napus and abundance in Brassicaceae species. Theor Appl Genet. 2001;102:689–694. doi: 10.1007/s001220051698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saal B, Plieske J, Hu J, Quiros CF, Struss D. Microsatellite markers for genome analysis in Brassica. II. Assignment of rapeseed microsatellites to the A and C genomes and genetic mapping in Brassica oleracea. Theor Appl Genet. 2001;102:695–699. doi: 10.1007/s001220051699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U N. Genome analysis in Brassica with special reference to the experimental formation of B. napus and peculiar mode of fertilization. Japan J Bot. 1935;7:389–452. [Google Scholar]

- Manly K, Cudmore R, Meer J. Mapmanager QTX, cross-platform software for genetic mapping. Mamm Genome. 2001;12:930–932. doi: 10.1007/s00335-001-1016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Chung TY, King GJ, Jin M, Yang TJ, Jin YM, Kim HI, Park BS. A sequence-tagged linkage map of Brassica rapa. Genetics. 2006;174:29–39. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.060152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kole C, Kole P, Vogelzang , Osborn TC. Genetic linkage map of a Brassica rapa recombinant inbred population. J Heredity. 1997;88:553–557. [Google Scholar]

- Teutonico RA, Osborn TC. Mapping of RFLP and qualitative trait loci in Brassica rapa and comparison to the linkage maps of B. napus, B. oleracea, and Arabidopsis thaliana. Theor Appl Genet. 1994;89:885–894. doi: 10.1007/BF00224514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwabe K, Iketani H, Nunome T, Kage T, Hirai M. Isolation and characterization of microsatellites in Brassica rapa L. Theor Appl Genet. 2002;104:1092–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-0875-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langercrantz U, Lydiate DJ. Comparative genome mapping in Brassica. Genetics. 1996;144:1903–1910. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YW, Lai KN, Tai PY, Li WH. Rates of nucleotide substitution in angiosperm mitochondrial DNA sequences and dates of divergence between Brassica and other angiosperm lineages. J Mol Evol. 1999;48:597–604. doi: 10.1007/PL00006502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwabe K, Tsukazaki H, Iketani H, Hatakeyama K, Kondo M, Fujimura M, Nunome T, Fukuoka H, Hirai M, Matsumoto S. Simple sequence repeat-based comparative genomics between Brassica rapa and Arabidopsis thaliana: the genetic origin of clubroot resistance. Genetics. 2006;173:309–319. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.038968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosambi D. The estimation of map distance from recombination values. Ann Eugen. 1944;12:172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kresovich S, Szewc-McFadden AK, Bliek SM, McFerson JR. Abundance and characterization of simple-sequence repeates (SSRs) isolated from a size-fractionated genomic library of Brassica napus L. (rapeseed). Theor Appl Genet. 1995;91:206–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00220879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LB, King GJ. The distribution of BoCAL-a alleles in Brassica oleracea is consistent with a genetic model for curd development and domestication of the cauliflower. Molec Breeding. 2000;6:603–613. doi: 10.1023/A:1011370525688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe AJ, Moule C, Trick M, Edwards KJ. Efficient large-scale development of microsatellites for marker and mapping applications in Brassica crop species. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;108:1103–1112. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1522-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brassica Microsatellite Information Exchange. http://www.brassica.info/ssr/SSRinfo.htm