Abstract

Presently, there is no effective treatment for preterm labor. The most obvious reason for this anomaly is that there is no objective manner to evaluate the progression of pregnancy through steps leading to labor, either at term or preterm. Several techniques have been adopted to monitor labor, and/or to diagnose labor, but they are either subjective or indirect, and they do not provide an accurate prediction of when labor will occur. With no method to determine preterm labor, treatment might never improve. Uterine EMG (electromyography) methods may provide such needed diagnostics.

Keywords: Labor, Parturition, Electromyography, Prediction, Gap Junction

1. Introduction

Throughout pregnancy, a woman’s uterus is essentially quiescent, while the cervix is rigid and closed. Normally at term, when the fetus is fully developed, the cervix then softens and dilates, and the uterus contracts vigorously to expel the fetus. However, in about 10% of pregnancies, these changes in the uterus and cervix occur earlier and result in preterm birth. Premature birth (and the attendant complications) are among the greatest health problems in the world today, and contribute to about 85% of all perinatal deaths [1, 2, 3]. Preterm infants with birth weights less than 2500 grams represent about 10% of the total number of babies born each year.

At the moment, there is no effective treatment for preterm labor. The key to treatment and prevention of preterm labor is early diagnosis.

2. Theoretical basis for electrical and physical activity

Uterine contractility is a direct consequence of the underlying electrical activity in the myometrial cells [4]. Spontaneous electrical activities in the muscle from the uterus are composed of intermittent bursts of spike action-potentials [5]. Uterine volume (chronic stretch) and ovarian hormones (principally estrogen), contribute to the change in action potential shape through their effect on resting membrane potentials [6, 7]. Single spikes can initiate contractions, but multiple, higher-frequency, coordinated spikes are needed for forceful and maintained contractions [5].

The action potentials in uterine smooth muscle result from voltage- and time-dependent changes in membrane ionic permeabilities. In longitudinal [8] and circular muscles of the uterus [9] the depolarizing phase of the spike is due to an inward current carried by Ca2+ ions and Na+ ions [10]. In preterm uterine muscle, the well-known “plateau-type” action potential may be due to a combined effect of a sustained inward Ca2+ or Na+ current and a decrease in the voltage-sensitive outward current [11].

The primary mode for elevation of Ca2+ is voltage-gated L-type channels, which are regulated by agonists. The increase in Ca2+ produces Ca-calmodulin and activates myosin light chain kinase. This phosphorylates myosin and a contraction occurs. The Na-Ca exchanger, along with the plasma membrane Ca-ATPase, both remove Ca2+, with 30 and 70 percent of the total efficacy, respectively [12]. The sarcoplasmic reticulum facilitates relaxation by releasing Ca2+ to the outgoing ion pathways, and also increases the rate of this process. The outward current causing re-polarization (studied in detail in longitudinal and assumed for circular muscles) is carried by K+ ions and consists of a fast (voltage-dependent) and slow (Ca2+ -activated) component [5,10]. There is contention that the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ targets K+ channels of the surface membrane and thus inhibits excitability, contributing to uterine relaxation. Some proteins have also been shown to control the electrical properties of the myometrium. The BK channel [13] and contractile activators [14] are examples (see England, 2007, this issue).

Isolated myometrial tissue studies (using microelectrodes or extracellular electrodes) have demonstrated the connection between electrical events and contractions [15, 16]. The frequency, amplitude, and duration of contractions are determined mainly by the frequency of occurrence of the uterine electrical bursts, the total number of cells that are simultaneously active during the bursts, and the duration of the uterine electrical bursts, respectively [5]. Each burst stops before the uterus has completely relaxed [5]. Agents that directly stimulate or inhibit uterine contractions do so by altering the electrical properties and the excitability or conductivity of myometrial cells.

3. Role of gap junctions in coordinated myometrial activity

Myometrial cells are coupled together electrically by gap junctions composed of connexin proteins [17]. This grouping of connexins provides channels of low electrical resistance between cells, and thereby furnishes pathways for the efficient conduction of action potentials. Throughout most of pregnancy, and in all species studied, these cell-to-cell channels or contacts are low, with poor coupling and decreased electrical conductance, a condition favoring quiescence of the muscle and the maintenance of pregnancy. At term, however, the cell junctions increase and form an electrical syncytium required for coordination of myometrial cells for effective contractions. The presence of the contacts seems to be controlled by changing estrogen and progesterone levels in the uterus [17].

This is demonstrated in the recording of human uterine electrical events (electromyographic signals, or EMG) acquired from the abdominal surface during pregnancy [18]. There is little uterine electrical activity, consisting of infrequent and low amplitude EMG bursts, throughout most of pregnancy. When bursts occur prior to the onset of labor, they often correspond to periods of perceived contractility by the patient. During term labor and during preterm labor, bursts of EMG activity are frequent, of large amplitude, and are correlated with the large changes in intrauterine pressure and pain sensation.

4. Evidence for pacemaker cells

Studies have been performed in an attempt to find specific types of cells that may act as pacemakers for the human uterus [19]. None have been found so far. It has therefore been suggested that the spontaneous electrical behavior exhibited by the myometrium is an inherent property of the smooth-muscle cells within the myometrium. Few direct studies of this proposal exist, though some recent pacemaker electrophysiological studies [20] demonstrated potentials that seemingly originate from impaled myocytes. The concept of variable uterine pacemakers has been on the table for many years, originating when no specific pacemakers were found early-on [16]. Apparently, any myometrial muscle cell is capable of acting as either a pacemaker or pace-follower [21].

Recently, these ideas have been born out, at least in a virtual sense, by successfully duplicating the observed action of the uterus, using a simulated myometrial model wherein the extent of electrical propagation, as well as the pacemaker current, could be varied. When the pacemaker activity was allowed to be generated randomly throughout the model, persistent and forceful contractions (not unlike in a laboring uterus) were generated [22].

Some early studies indicated that there may be a preferential direction of propagation in the human uterus [16, 23]. For geometrical and physical reasons, this presumably could aid in the expulsion of the fetus if contractions propagate generally from the fundus toward the isthmus during active labor. This would support the notion that although there may not be a specific type of individual pacemaker cell, there may be general pacemaker regions later in gestation. But so far, no clear direct evidence of them has been found in humans, but perhaps the idea should be re-visited, with more extensive studies being done which examine the fundus vs. isthmus portions of the uterus, looking for regional electrochemical differences (e.g. ion currents, cellular resting and threshold potentials, gap junction density, etc. see esp. 24) or perhaps even hormonal- or protein- concentration differences in the different locations of the uterus that may be responsible for the onset of this directional-propagation phenomenon in late-gestation.

5. Interrelationship of the uterus and cervix

Some have described the cervix as an entirely separate organ, while many others consider it to be a specialized extension of the uterus. Indeed, there are similarities and differences: both the uterus and cervix appear to be regulated in part by prostaglandins [25], and both contain smooth muscle tissue, which may contract [26, 27], and both contain collagen as well. However, the cervix is composed mainly of collagen, with little muscle content, while the uterus is made up mostly of smooth muscle tissue, with less collagen than the cervix. In fact, uterine electrical signals may actually propagate through the cervix too, and so any observed cervical contracting may actually be the result of “driving” by the electrically-active uterus, at least early in gestation (when the cervix should remain closed) and prior to the onset of labor. After that, electrical coupling between the uterus and cervix may be inconsequential for normal term labor, with the forceful contractions of the uterus likely being strong enough during the later stages to overcome any passive (or active) resistance to dilation and delivery that the cervix may offer. Some studies supporting this have demonstrated that in late-gestation, either reduced or no electromechanical activity is observed from the human cervix [26, 28]. However, the dynamic balance between the uterine and any cervical forces would be critical in preterm labor, where the uterus is not as well developed and consequently the labor is less efficient.

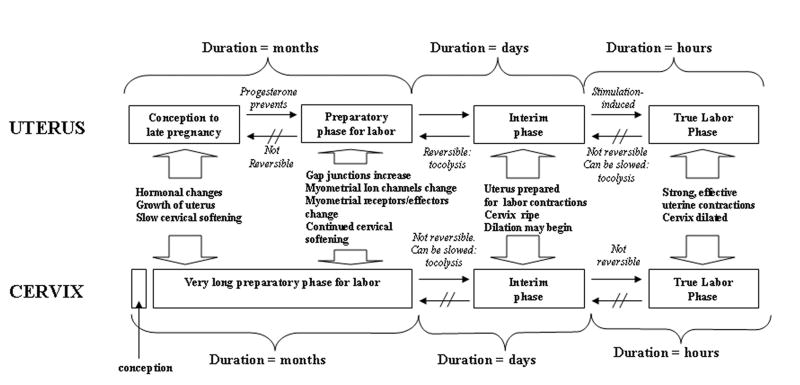

Parturition is composed of two major steps (Figure 1): a relatively long conditioning (preparatory) phase, followed by a short secondary phase (active labor) [29]. These two might also be separated by a critical “interim phase,” after which treatments for the prevention of labor may become ineffective. The conditioning step leading to the softening of the cervix takes place in a different time frame from that of the uterus, indicating that the myometrium and the cervix are regulated, at least in part, by independent mechanisms. In the myometrium, this preparatory process involves changes in transduction mechanisms and the synthesis of several new proteins including connexins, ion channels and receptors for uterotonins. At the same time, there is a down-regulation of the nitric oxide system, which leads to withdrawal of uterine relaxation. In the cervix, the transition involves a change in the composition of the connective tissue and the invasion by inflammatory cells.

Fig. 1.

A model of maturation for the uterus and cervix, from conception to delivery. The uterine and cervical steps to normal development occur over different time scales and gestations. However, the interim phase, just prior to dilation and before forceful and effective contractions, might be the final chance to treat most patients who are experiencing initial preterm labor symptoms.

Ultimately (at the end of the interim phase), these processes become irreversible, leading to active labor and delivery. Once active labor has begun, delivery might not be delayed for more than several days in humans, because the changes which occurred in the preparatory phase have by this time become well established and cannot be reversed, at any rate not with currently available tocolytics.

6. Noninvasive monitoring

6.1 Overview

The current state of the art in monitoring labor can be summarized as follows: intrauterine pressure catheters are limited by their invasiveness and the need for ruptured membranes; present external uterine monitors are uncomfortable, often inaccurate, and depend on the subjectivity of the examiner; methods now used do not make direct measurements of the properties that control both the function and state of the uterus or the cervix during pregnancy, and have not reliably predicted nor lead to treatment of preterm labor.

While a few currently used techniques [30] can identify some of the signs of oncoming labor, none of them offer objective data that accurately predicts labor over a broad range of patients. In forecasting pre-term labor and delivery, the capability of the technologies already generally accepted into clinical practice are limited, especially by their sensitivity and positive predictive values, in contrast to EMG and light-induced fluorescence (LIF) [30, 31, 32; Table 1]:

Table 1. Comparison of Technologies for Predicting Preterm Labor .

Tests = multiple preterm labor symptoms (MPTLS), contractions >4/hr (Ctx≥4/hr), Bishop Score >4 (BS≥4), cervical length <25 mm (Cx≤25mm), fetal fibronectin (FFN+), salivary estriol (Salivary E3), uterine electromyographic activity(EMG), and light induced fluorescence (LIF). Sensitivity and specificity are indicated by Sens and Spec and positive (PPV) and negative predictive (NPV) values for the various tests.

| Test | Sens | Spec | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPTLS | 50.0 | 63.5 | 21.4 | 86.4 |

| Ctx ≥ 4/hr | 6.7 | 92.3 | 25.0 | 84.7 |

| BS ≥ 4 | 32.0 | 91.4 | 42.1 | 87.4 |

| Cx ≤ 25mm | 40.8 | 89.5 | 42.6 | 88.8 |

| CFFN + | 18.0 | 95.3 | 42.9 | 85.6 |

| EMG | 75.0 | 93.3 | 81.8 | 90.3 |

| LIF | 59.0 | 100.0 | 78.9 | 80.0 |

Sens (Sensitivity)

Spec (Specificity)

PPV (Positive predictive value)

NPV (Negative predictive value)

MPTLS = Multiple preterm labor symptoms

Ctx = Maximal uterine contractions (measured with TOCO)

BS = Bishop score

Cx = Cervical length (measured with ultrasound)

CFFN = Cervical fetal fibronectin test

EMG = Noninvasive transabdominal uterine electromyogram

LIF = Cervical light-induced fluorescence

Multiple preterm labor symptoms include cervical dilation and effacement, vaginal bleeding, or ruptured membranes. These signs are determined by a clinician, but they have had minimal success in reducing preterm labor rates over the past decade. Maximal uterine contractions represent the highest observed number of contraction events seen in any 10-minute period. This is assessed by a clinician using a tocodynamometer (TOCO). However, TOCO has been shown to be unreliable as a predictor for preterm or even term labor [33, 34; Figure. 2A, B, C]. The Bishop scoring system attempts to predict the success of induction by assessing five factors: position of the cervix in relation to the vagina, cervical consistency, dilation, effacement and station of the presenting part. Bishop scoring has not lead to a reduction in preterm labor. The length of the cervix via endovaginal ultrasonography has been used to detect premature labor (35, 36), with some limited degree of success. However, predictive values are obtained only after the onset of preterm labor symptoms, so this instrument’s application is limited, as is the potential for treatment upon diagnosis using this method. Furthermore, the measurement of the cervical length is made unreliable by varying amounts of urine in the bladder [30, esp. see p. 407]. Direct cervical examination has proven to be no better [37]. Assay of cervical or vaginal fetal fibronectin (FFN) has recently been suggested as a screening method for patients at risk for premature labor. Results from some studies [30, 38] show that FFN might be used to predict actual premature labor. Other studies indicate that FFN has limited value [39]. The real value of the FFN assay lies in its high negative predictive value (NPV); it has the ability to identify patients that are NOT at risk of premature labor. Similarly, salivary estriol has been shown to have some use because of its high NPV [40].

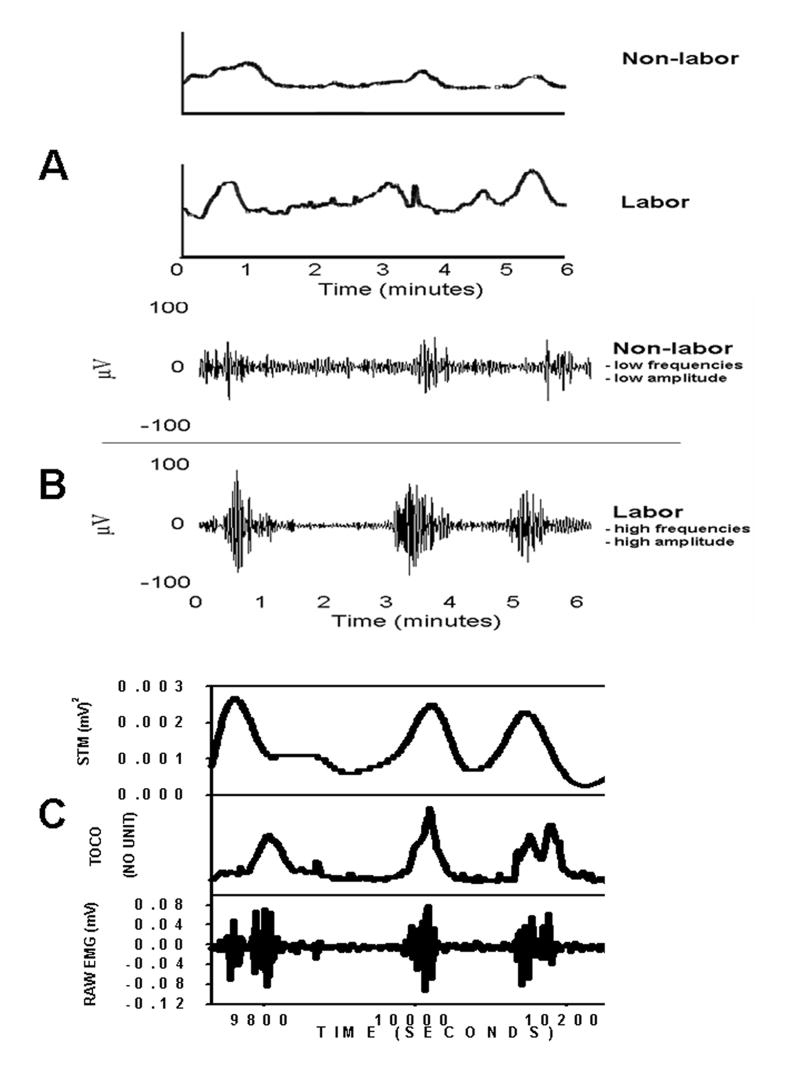

Fig. 2.

A.) Tocodynamometer (TOCO) recordings from a patient in term labor (bottom trace) and from a term non-labor patient (top trace). Note that the approximate contraction rates, and even some of the amplitudes, are equal. This is problematic for the instrument’s user when using the TOCO device to distinguish between the two patient types. These types of failure often occur when the TOCO device is utilized in the clinic. Nevertheless, clinicians have become accustomed to using them, despite the shortcomings of the instrument. B.) On the other hand, differences clearly manifest themselves (some of which can be discerned visually and some which must be calculated) when comparing the uterine EMG recording of a term labor patient (bottom trace) to a term non-labor patient (top trace). Labor patient uterine EMG’s generally possesses higher burst amplitudes and higher action potential frequencies within each burst than those of non-labor patients. C.) In the future, real-time raw EMG signals (bottom trace) could be converted to “TOCO-like” signals (top – trace; using spectral temporal mapping – STM – for example) to facilitate the ease of translation by physicians in the clinic. Compare this to the irregular and difficult-to-interpret trace (middle trace) produced simultaneously by the TOCO on the same patient.

6.2 Uterine EMG acquisition and analysis

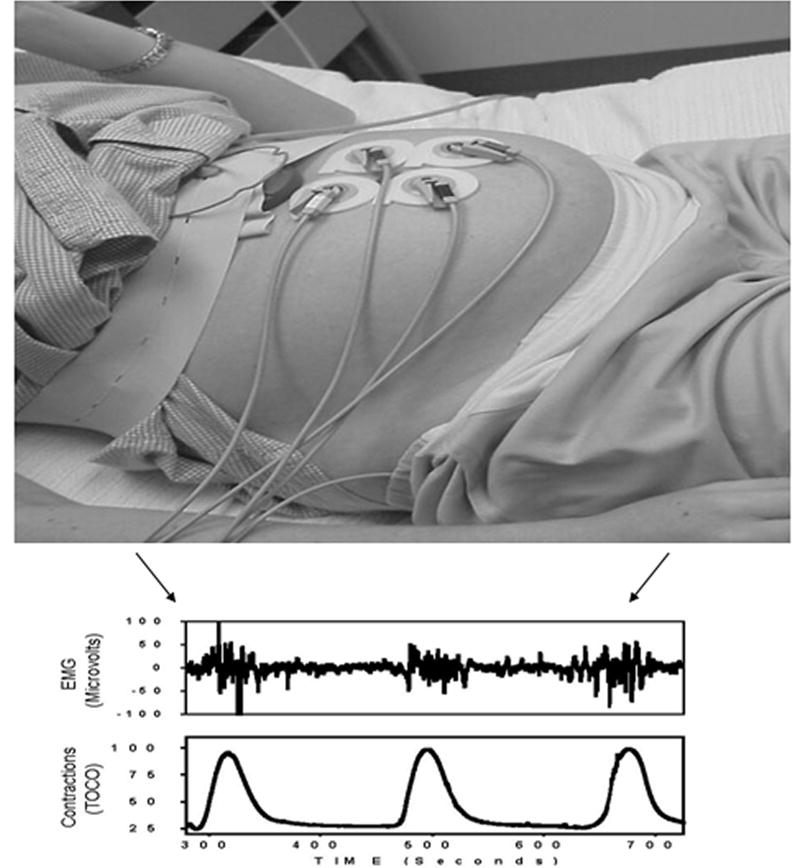

Both the electrical and the mechanical activity of the uterus - in various species [41], including humans [16] - have been recorded from the uterus directly. Our studies, as well as those of others [42, 43], provide convincing evidence that uterine EMG activity can be appraised from non-invasive trans-abdominal surface measurements (Figure 3), and can be a powerful tool in characterizing parturition.

Fig 3.

Typical uterine EMG setup includes abdominal surface electrodes, electrical filters/amplifiers and acquisition and analysis hardware/software. The EMG bursts that are responsible for uterine contractions are shown in clear temporal correspondence with the simultaneous TOCO output. However, the TOCO can only measure contraction rate and (crudely and inaccurately) contraction amplitude. The uterine EMG signals, on the other hand, can be analyzed by a number of sophisticated mathematical methods (power spectrum, wavelets, fractals, and artificial neural networks to name a few) in order to determine the extent of electrochemical preparedness of the myometrium for labor and subsequent delivery.

6.3 Recent uterine EMG applications

The non-invasive trans-abdominal uterine EMG method has been applied in a number of studies involving various patient types and employing numerous analytic methods. The following is a brief description of some of the newest results:

PDS has proved to be useful in quantifying uterine EMG [32]. Maternal age does not seem to affect uterine contractile electrical activity for patients at term and in labor when characterizing the activity with PDS. We have recorded uterine EMG non-invasively with electrodes from the abdominal surface in 40 laboring patients at term. Bursts of uterine electrical activity corresponding to contractions were analyzed with PDS analysis to find the greatest-magnitude peak residing in the 0.34Hz to 1.00Hz range. No significant differences in the PDS peak frequency parameter were noted when women < 35 years-old (n=34) were compared to those ≥ 35 years-old (0.49 ± 0.02 vs. 0.51 ± 0.06 Hz) or when women < 30 years-old (n=31) were compared to those ≥ 30 years-old (0.49 ± 0.02 vs. 0.50 ± 0.04 Hz). No correlation was found between patient age and the PDS parameter.

Uterine EMG PDS peak frequency also does not appear to be affected by patient parity. We looked at uterine EMG in term laboring patients that were grouped into the following sets: parity = 0; parity = 1; parity = 2; parity > 2. Subsequently, a fifth group was formed for parity > 0. PDS peak frequency (mean±SD) was as follows: 0.48 ± 0.11; 0.49 ± 0.07; 0.49 ± 0.09; 0.61 ± 0.17; 0.51 ± 0.10. No significant differences were seen between any of the groups. No correlation was found for patient parity and PDS peak frequency.

These studies imply that the PDS peak frequency variable may have more utility over other more traditional signal-diagnostic EMG parameters for the assessment of patient uterine activity both prior to and during the onset of labor, since variations in maternal age and parity from patient to patient will not adversely affect the analysis. This is consistent with recent animal studies [44] on uterine EMG. Similar examinations on other EMG parameters should also be performed.

Relatively new (that is, to applications in obstetrics) mathematical approaches such as wavelets, fractals, and neural networks, have all been applied to recorded uterine EMG signals for the purpose of assessing pregnant patients by looking, for example, at differences in labor vs. non-labor signal qualities [45]. For instance, wavelets are a way of separating out frequency bands (wavelet “scales”) within signals. We have found that an energy transition from the lower wavelet scales to the higher wavelet scales occurs within 24 hours of delivery in pregnant women. Similarly, fractal dimension (which is a way to characterize the amount of “waviness” in signals) also exhibits a change when patients transition from non-labor (ante-partum) to labor [45]. Such transition could prove valuable in differentiating between true and false labor and in predicting delivery. Artificial, or simulated, neural networks (NN’s), on the other hand, are programs that use extremely new mathematical models or algorithms that recognize and identify patterns in data [46]. NN’s were inspired by biological learning research. Biological learning occurs by example and is driven by information (data) methodologies, rather than rules. NN’s also learn by themselves from the data, and do not need defined rules that describe problems, similar to the actual neurological function in living brains. Our most recent study showed NN’s to be excellent at discerning labor [47].

These and other novel approaches to using uterine EMG data may one day make the technique routine for the monitoring and management of patients during pregnancy and parturition.

6. Conclusions

Diagnostic methods that have been shown to have greater predictive capability than the presently-utilized and clinically-accepted tests must also be seriously considered as viable candidates for clinical use. Such is seen to be the case for the uterine EMG device, when comparing its capabilities against those of other “predictive” technologies. Furthermore, none of the current tests can offer (during pregnancy and parturition) the direct objective measurement of both the function and the state of the uterus that the uterine EMG monitor provides the clinician. Such fundamental measurements, we believe, are essential for proper patient classification and management, and hence for proper treatments during pregnancy.

Physicians would likely already be using the uterine EMG and instrument in the clinic today if they were more familiar with its advantages. With further refinements, these tools could be routinely used with little or no training required for the practitioner. There is a tremendous need for, and potentially great benefits from, this technology. The implementation of it would likely lead to better patient care, with a corresponding reduction in infant mortality and morbidity.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Shao-Qing Shi and Lynnette B. MacKay for their help in collecting and maintaining data. Supported by NIH grants RO1-37480

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services: An Assessment of the Effectiveness of 169 Interventions. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown ER, Epstein M. Immediate consequences of preterm birth. In: Fuchs F, Stubblefield PG, editors. Preterm birth: causes, prevention, and management. New York: Macmillan Publishing; 1984. p. 323. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown ER. Long-term sequelae of preterm birth. In: Fuchs F, Stubblefield PG, editors. Preterm birth: causes, prevention, and management. New York: Macmillan Publishing; 1984. p. 333. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kao CY. Electrical properties of uterine smooth muscle. In: Wynn RM, editor. Biology of the Uterus. Plenum Press; New York: 1977. pp. 423–496. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall JM. Regulation of activity in uterine smooth muscle. Physiol Rev. 1962;42:213–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osa T, Ogasawara T, Kato S. Effects of magensium, oxytocin and prostaglandin F2 on the generation and propagation of excitation in the longitudinal muscle of rat myometrium during late pregnancy. Jpn J Physiol. 1983;33:51–67. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.33.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bengtsson B, Chow EMH, Marshall JM. Activity of circular muscle of rat uterus at different times in pregnancy. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:C216–C223. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1984.246.3.C216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vassort G. Ionic currents in longitudinal muscle of the uterus. In: Bulbring E, Brading AF, Jones AW, Tomita T, editors. Smooth Muscle: an Assessment of Current Knowledge. Edward Arnold; London: 1981. pp. 353–366. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chamley WA, Parkington HC. Relaxin inhibits the plateau component of the action potential in the circular myometrium of the rat. J Physiol Lond. 1984;353:51–65. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuriyama H. Excitation-contraction coupling in various visceral smooth muscles. In: Bulbring E, Brading AF, Jones AW, Tomita T, editors. Smooth Muscle: an Assessment of Current Knowledge. Edward Arnold; London: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawarabayashi T. The effects of phenylephrine in various ionic environments on the circular muscle of midpregnant rat myometrium. Jpn J Physiol. 1978;28:627–645. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.28.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matthew A, Shmygol A, Wray S. Ca2+ entry, efflux and release in smooth muscle. Biol Res. 2004;37(4):617–24. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602004000400017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan R, Mathroo-Ball B, Arilkumaran S, Aahford MLJ. Potassium channels in the human myometrium. Exp Physiol. 2001;86:255–264. doi: 10.1113/eph8602181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Challis JR, Lye SJ, Gibb W, Whittle W, Patel F, Alfaid YN. Understanding preterm labor. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;943:225–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall JM. Effects of estrogen and progesterone on single uterine muscle fibers in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1959;197:935–942. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1959.197.4.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfs GMJA, Rottinghuis H. Electrical and mechanical activity of the human uterus during labour. Arch Gynakol. 1970;208:373–385. doi: 10.1007/BF00668252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garfield RE, Yallampalli C. Structure and Function of Uterine Muscle. The Uterus. In: Chard T, Grudzinskas JG, editors. Cambridge Reviews in Human Reproduction. 1994. pp. 54–93. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devedeux D, Marque C, Monsour S, Germain G, Duchene J. Uterine electromyography: A critical review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:1636–1653. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90456-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duquette RA, Shmygol A, Vaillant C, Mobasheri A, Pope M, Burdyga T, Wray Susan. Vimentin-Positive, c-KIT-Negative Interstitial Cells in Human and Rat Uterus: A Role in Pacemaking? BIOLOGY OF REPRODUCTION. 2005;72:276–283. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.033506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parkington HC, Coleman HA. Excitability in uterine smooth muscle. Front Horm Res. 2001;27:179–200. doi: 10.1159/000061026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kao CY. Long-term observations of spontaneous electrical activity of the uterine smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1959 Feb;196(2):343–50. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1959.196.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benson AP, Clayton RH, Holden AV, Kharche S, Tong WC. Endogenous driving and synchronization in cardiac and uterine virtual tissues: bifurcations and local coupling. Philos Transact A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2006 May 15;364(1842):1313–27. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2006.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Planes JG, Morucci JP, Grandjean H. Favretto. External recording and processing of fast electrical activity of the uterus in human parturition. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1984 Nov;22(6):585–91. doi: 10.1007/BF02443874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar D, Barnes C. Studies in human myometrium during pregnancy. II. Resting membrane potential and comparative electrolyte levels. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1961;82:736–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)36136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hertelendy F, Zakar T. Prostaglandins and the myometrium and cervix. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004 Feb;70(2):207–22. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olah KS. Changes in cervical electromyographic activity and their correlation with the cervical response to myometrial activity during labour. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994 Dec;57(3):157–9. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(94)90292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pajntar M, Verdenik I, Pusenjak S, Rudel D, Leskosek B. Activity of smooth muscles in human cervix and uterus. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998 Aug;79(2):199–204. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shafik A. Electrohysterogram: study of the electromechanical activity of the uterus in humans. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997 May;73(1):85–9. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(97)02727-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garfield RE, Yallampalli C. Control of myometrial contractility and labor. In: Chwalisz K, Garfield RE, editors. Basic Mechanisms Controlling Term and Preterm Birth. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1993. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iams JD. Prediction and Early Detection of Preterm Labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(2):402–412. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02505-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maul H, Saade G, Garfield RE. Prediction of term and preterm parturition and treatment monitoring by measurement of cervical cross-linked collagen using light-induced fluorescence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005 Jun;84(6):534–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maner WL, Garfield RE, Maul H, Olson G, Saade G. Predicting term and preterm delivery with transabdominal uterine electromyography. Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Jun;101(6):1254–60. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maul H, Maner WL, Olson G, Saade GR, Garfield RE. Non-invasive transabdominal uterine electromyography correlates with the strength of intrauterine pressure and is predictive of labor and delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004 May;15(5):297–301. doi: 10.1080/14767050410001695301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dyson DC, Dange KH, Bamber JA, Crites YM, Field DR, Maier JA, Newman LA, Ray DA, Walton DL, Armstrong MA. Monitoring women at risk for preterm labor. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:15–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801013380103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, Mercer BM, Moawad A, Das A, Thom E, McNellis D, Copper RL, Johnson F, Roberts JM. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. N Eng J Med. 1996;334:567–572. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romero R. The uterine cervix, ultrasound and prematurity. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1992;2(6):385–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1992.02060384-2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Dubard MB, Hauth JC, Cutter GR. Cervical examination and tocodynamometry at 28 weeks’ gestation: Prediction of spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:666–671. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lockwood CJ. Biochemical predictors of prematurity. Front Horm Res. 2001;27:258–268. doi: 10.1159/000061031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hellemans P, Gerris J, Verdonk P. Fetal fibronectin detection for prediction of preterm birth in low risk women (see comments) Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;102:207–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb09095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGregor JA, Jackson GM, Lachelin GC, Goodwin TM, Artal R, Hastings C, Dullien V. Salivary estriol as risk assessment for preterm labor: a prospective trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1337–1342. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Csapo AI. Force of labour. In: Iffy L, Kamientzky HA, editors. Principles and Practice of Obstetrics and Perinatology. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1981. pp. 761–799. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buhimschi C, Boyle MB, Garfield RE. Electrical activity of the human uterus during pregnancy as recorded from the abdominal surface. Obstet and Gynecol. 1997;90:102–111. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)83837-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duchêne J, Devedeux D, Mansour S, Marque C. Analyzing uterine EMG: Tracking instantaneous burst frequency. IEEE Eng Med Bio. 1995 March/April;:125–132. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doret M, Bukowski R, Longo M, Maul H, Maner WL, Garfield RE, Saade GR. Uterine electromyography characteristics for early diagnosis of mifepristone-induced preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Apr;105(4):822–30. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000157110.62926.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maner WL, MacKay LB, Saade GR, Garfield RE. Characterization of abdominally acquired uterine electrical signals in humans, using a non-linear analytic method. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2006;44:117–123. doi: 10.1007/s11517-005-0011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naguib R. Artificial neural networks in cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and patient management. CRC Press; LLC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maner WL, Garfield RE. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007. Jan 17, Identification of Human Term and Preterm Labor using Artificial Neural Networks on Uterine Electromyography Data. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]