Abstract

The commonly used anesthetic agent, isoflurane (ISO), is a potent coronary vasodilator which could potentially be used in the assessment of coronary reserve, but its effects on coronary blood flow in mice are unknown. Coronary reserve is reduced by age, coronary artery disease, and other cardiac pathologies in man, and some of these conditions can now be modeled in mice. Accordingly, we used Doppler ultrasound to measure coronary flow velocity in mice anesthetized at low (1%) and at high (2.5%) levels of ISO to generate baseline (B) and elevated hyperemic (H) coronary flows respectively. A 20 MHz Doppler probe was mounted in a micromanipulator and pointed transthoracically toward the origin of the left main coronary arteries of 10 6-wk (Y), 10 2-yr (O), and 20 2-yr apolipoprotein-E null (ApoE−/−) atherosclerotic (A) mice. In each mouse we measured (B) and (H) peak diastolic velocities. B was 35.4 +/− 1.4 cm/s (Y), 24.8 +/− 1.6 (O), and 51.7 +/− 6.4 (A); H was 83.5 +/− 1.3 (Y), 86.5 +/− 1.9 (O), and 120 +/− 16.9 (A); and H/B was 2.4 +/− 0.1 (Y), 3.6 +/− 0.2 (O), and 2.5 +/− 0.2 (A). The differences in baseline velocities and H/B between O and Y and between A and O were significant (P < 0.01), while the differences in hyperemic velocities were not (P > 0.05). H/B was higher in old mice due to decreased baseline flow rather than increased hyperemic flow velocity. In contrast ApoE−/− mice have increased baseline and hyperemic velocities perhaps due to coronary lesions. The differences in baseline velocities between young and old mice could be due to age-related changes in basal metabolism or to differential sensitivity to isoflurane. We conclude that Doppler ultrasound combined with coronary vasodilation via isoflurane could provide a convenient and noninvasive method to estimate coronary reserve in mice, but also that care must be taken when assessing coronary flow in mice under isoflurane anesthesia because of its potent coronary vasodilator properties.

Keywords: Doppler ultrasound, Noninvasive, Cardiovascular physiology, Hyperemia, Hypertrophy

Introduction

The noninvasive measurement of coronary blood flow by ultrasound has been notoriously difficult in both man and animals because coronary arteries are small, are highly branched, lie deep within the chest, and are in constant motion due to their attachment to the epicardial surface. Thus, measurements of coronary flow or velocity have required the use of invasive methods such as implantable flow probes (Hartley and Cole, 1974) or coronary catheters (Cole and Hartley, 1977; Sibley et al., 1986; Wilson et al., 1985). In addition, coronary blood flow (even if it could be measured accurately) is often normal at rest even in the presence of severe coronary artery disease (Gould et al., 1974; Marcus et al., 1981). This problem is commonly addressed by administering a coronary vasodilator such as adenosine (Hoffman, 1984; Marcus, 1983) to increase blood flow and then measuring the ratio of maximum hyperemic flow to resting baseline flow as an index of coronary vascular reserve (Gould et al., 1974). Coronary vascular reserve has been shown to be reduced in the presence of coronary lesions due to a reduction in hyperemic flow (Marcus et al., 1981), and by other cardiac pathologies due to an increase in baseline flow(Marcus et al., 1982; Marcus, 1983).

The apolipoprotein-E deficient mouse (ApoE−/−) is a commonly used model of atherosclerosis because the arterial lesions resemble those found in humans at certain stages of the disease (Nakashima et al., 1994; Paigen et al., 1987). Although the atherosclerotic lesions are progressive and may become severe, their functional effect on blood flow and physiology is largely unknown. Cardiovascular reserve relevant to exercise performance is reduced (Niebauer et al., 1999), and we have previously shown a 55% increase in aortic and mitral flow velocities and a 59% increase in heart-weight to body-weight ratio at 1 year of age (Hartley et al., 2000) consistent with volume overload hypertrophy. However, the effect and significance of systemic and coronary arterial lesions and of the cardiac hypertrophy on coronary blood flow and coronary flow reserve in ApoE−/− mice is unknown.

The administration of a specific and maximal coronary vasodilator such as adenosine (Wikstrom et al., 2005) is necessary to evaluate coronary flow reserve, and this is much more difficult and problematic in mice where the veins are more difficult to cannulate and the tolerated doses and volumes are much smaller. Fortuitously, one of the most widely used anesthetic agents (isoflurane gas) is also a coronary vasodilator when administered at higher concentrations (Crystal, 1996; Gamperi et al., 2002; Reiz et al., 1983; Zhou et al., 1998). The use of an inhaled coronary vasodilator, if effective and well-tolerated, would greatly simplify the estimation of coronary flow reserve in mice and make the procedure truly noninvasive and amenable to high throughput. Although it is known to lower systemic blood pressure (Zuurbier et al., 2002), isoflurane is now the preferred anesthetic for performing cardiovascular studies in mice because it has minimal effects on heart rate when compared to other nonvolatile agents (Jannsen et al., 2004). However, the ability of isoflurane gas to dilate coronary arteries and increase coronary blood flow is often unrecognized, and the required concentrations and responses are undocumented in mice.

During the last decade there have been several reports on the use of noninvasive Doppler ultrasound to estimate coronary flow reserve in man using adenosine (Neishi et al., 2005), dipyridamole (Galderisi et al., 2004; Santagata et al., 2005; Saraste et al., 2001), or dobutamine (Cicala et al., 2004) to increase coronary flow. However, because it is difficult to locate and identify specific coronary lesions, these methods have not achieved wide acceptance and are not routinely used in assessing the relationship between anatomy and functional significance in patients with coronary artery disease (Rigo, 2005; Voci et al., 2004). Recently there have also been reports showing coronary flow velocity signals recorded from mice using conventional echocardiography machines (Gan et al., 2005; Wikstrom et al., 2005) or a high-frequency scanner designed specifically for mice (Zhou et al., 2004). Although the signals shown were identifiable and quantifiable, they were often of sub-optimal quality and fidelity. This encouraged us to test the feasibility of using a smaller and more focused Doppler probe to measure coronary flow velocity and to estimate reserve in a mouse model of atherosclerosis (Plump et al., 1992; Wang, 2005) where we hypothesized that the presence of lesions in the left main coronary artery (Wikstrom et al., 2005) coupled with volume overload hypertrophy (Hartley et al., 2000) would reduce coronary flow reserve. Thus, we report here a noninvasive method using Doppler ultrasound (Hartley et al., 2000) to measure left main coronary flow velocity and the response to low and high levels of inhaled isoflurane in young and old wild-type, and old (age-matched) ApoE−/− mice (Bernard et al., 1992; Crystal, 1996). We use the response to isoflurane to document systematic differences in baseline and hyperemic coronary flow velocity among the groups and to demonstrate large variations in baseline and hyperemic coronary artery velocities in ApoE−/− mice likely due to the presence of stenotic coronary artery lesions.

Methods

Animal protocol

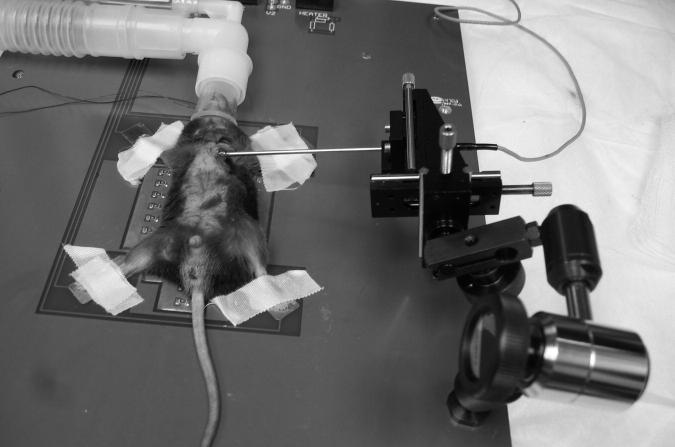

Three groups totaling 40 mice were studied following a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Baylor College of Medicine. The groups consisted of 10 young C57BL6 wild-type, 10 old ApoE+/+ wild-type, and 20 old ApoE−/− knockout mice. The 2-year old ApoE−/− mice and their wild-type age-matched controls were derived from a C57BL6 background and were obtained from a colony at Berlex Biosciences, Richmond, California. All mice were anesthetized in a closed chamber with 3% isoflurane in oxygen for 2 to 5 minutes until immobile. Each mouse was then removed, weighed, and taped supine to ECG electrodes on a heated procedure board (MousePad, Indus Instruments, Houston, TX, USA) (Hartley et al., 2002) with isoflurane (initially at 2%) supplied by a nose cone connected to the anesthesia machine (Model V-1 with Isoflurane Vaporizer, VetEquip, Pleasanton, CA, USA). The board temperature was maintained at 35-37 °C. Next a 2 mm diameter 20 MHz Doppler probe was connected to a Doppler Signal Processing Workstation (Model DSPW, Indus Instruments, Houston, TX, USA) and clamped in a micromanipulator (Model MM3-3, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) also attached to the procedure board for stability as shown in Figure 1. The clamp on the manipulator gimbal was loosened, and the probe tip was placed on the left chest at the level of the cardiac base and pointed horizontally toward the anterior basal surface of the heart to sense blood flow velocity in the aorta or in the left main coronary artery at a 2.5 mm depth setting. If aortic velocity signals were found first, the sample volume depth was reduced. If coronary velocity signals were found first, the sample volume was advanced until aortic signals were found and then moved back into the left main coronary artery. Coronary flow signals were identified on the Doppler spectral display by flow toward the probe peaking in early diastole and then decaying and being minimal during systole as illustrated in Figure 2. Once the left main coronary flow signal was obtained, the clamp was tightened, and the sample volume position was adjusted using the depth gate and the three-axis verniers on the manipulator to maximize the velocity and signal strength as seen on the spectral display. In this orientation, the sound beam was nearly parallel to the axis of the left main coronary artery such that angle correction was not used to calculate velocity from the Doppler frequency. After a stable signal was achieved, a two-second sample of the ECG and the raw quadrature Doppler signals was acquired and stored in a computer file for later analysis (Reddy et al., 2005b; Reddy et al., 2005a). Then the isoflurane was reduced to 1% to lower coronary flow to a baseline level. After 3-5 minutes or when flow became stable at the low level, the sample volume was readjusted to maximize velocity and signal strength, and another two-seconds of signals were collected and stored. Then the isoflurane level was increased to 2.5% to increase coronary flow, and when velocity was stabilized and optimized, more signals were stored and isoflurane was again reduced to 1% and allowed to stabilize. During this procedure as coronary blood flow was increased and decreased, a total of 10-15 2-second acquisitions were made to ensure that the maximum and minimum values of coronary velocity were recorded.

Figure 1.

Photo of set-up showing an anesthetized mouse taped to ECG electrodes and over the heating elements of the procedure board and a 3-axis micromanipulator holding a 20 MHz Doppler probe pointed toward the left main coronary ostia.

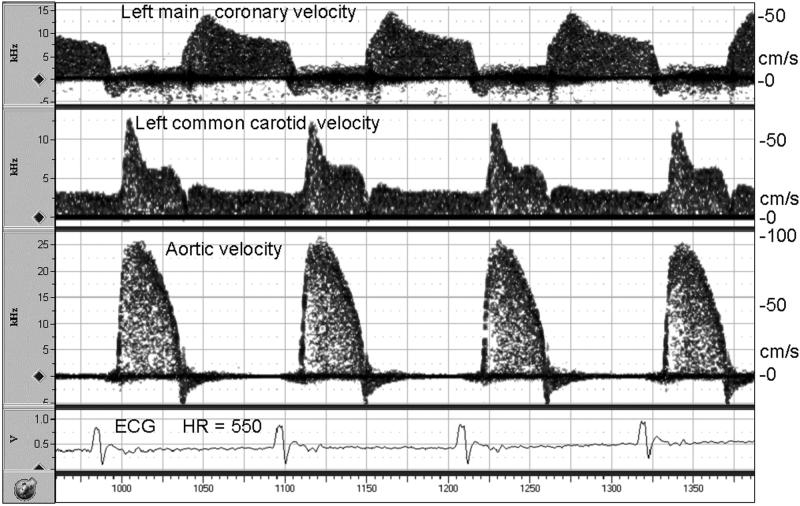

Figure 2.

Simultaneous Doppler signals from the coronary artery, carotid artery, and aorta in a mouse anesthetized with 2% isoflurane showing the timing relative to the ECG and the similarity to human signals in each vessel. One Doppler probe was positioned as in Figure 1, a second was pointed toward the aortic root from the right sternal border, and a third was pointed at 45 degrees toward the left common carotid artery in the neck. Blood velocities in cm/s were calculated from the Doppler shifts using the Doppler equation with a Doppler angle of 0 degrees for the coronary artery and the aorta and 45 degrees for the carotid artery.

Instrumentation and data analysis

The Doppler instrumentation consisted of a 2 mm diameter 20 MHz single-element ultrasonic transducer focused at 4 mm and connected to a 20 MHz pulsed Doppler instrument both of which were constructed in our laboratory (Hartley et al., 2002). The Doppler instrument was optimized for use in mice by setting the burst length to 8 cycles (400 ns) and the pulse repetition frequency to 125 kHz. These settings allow the measurement of velocities as high as 4.5 m/s at a maximum sample volume depth of 6 mm. The quadrature audio signals from the pulsed Doppler were connected to the Doppler signal processing workstation (Model DSPW, Indus Instruments, Houston, TX, USA) (Reddy et al., 2005a).

Data (quadrature audio Doppler signals and lead 2 ECG) were sampled at 125 kHz and stored in 2-second files on a personal computer for later analysis. During analysis the Doppler signals were displayed on the workstation and converted to velocity (V) using the Doppler equation: V = Δf c/2fo cosθ, where Δf is the Doppler frequency, c is the speed of sound in blood (∼1,570 m/s), fo is the ultrasonic frequency (20 MHz), and θ is the angle between the sound beam and the direction of flow (0 degrees). The average peak diastolic velocity (PDV) was measured by placing a calibrated curser over the spectral peaks and averaging the peak of each beat during the 2-second interval. Heart rate (HR) was determined automatically from the R-R interval of the ECG. Thus, for each data file we tabulated HR and PDV. The hyperemic to baseline ratio of coronary flow (H/B) was calculated as the ratio of PDV at the highest flow attained during the high level of isoflurane (H) to PDV at the minimum baseline flow obtained at the lowest level of isoflurane (B). Data are presented as mean +/−SEM, and statistical significance is defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Coronary flow velocity signals were obtained in all animals under baseline and hyperemic flow conditions. As illustrated in Figure 2, the signal-to-noise ratio and fidelity of coronary velocity signals from mice were similar in quality to signals from other vessels such as the ascending aorta and carotid arteries. To generate this illustration two additional Doppler probes and modules were used to record all signals simultaneously (Hartley et al., 1978). The velocity signals from the left main coronary arteries were identified by the timing and shape of the waveform and by the presence of aortic velocities 1 mm farther along the sound beam. Note that during the initial probe placement, with isoflurane concentration at 2%, coronary velocity is elevated above baseline making it easier to locate the signal.

Table 1 shows a summary of the characteristics and data from each group of mice at baseline and at maximum hyperemic flow. There were significant differences in the body weights of the Young and Old groups and of the Old and ApoE−/− groups, but there were no differences in the baseline or hyperemic heart rates between any of the groups. Heart rate was increased above baseline by 5% to 14% at the high levels of isoflurane, but the differences between groups were not statistically significant. The baseline coronary velocities were significantly different between the groups, but the hyperemic velocities were not. The H/B ratio was statistically different between the Old mice (3.6 +/− 0.2) and Young mice (2.4 +/− 0.1) and between the ApoE−/− mice (2.5 +/− 0.2) and their age-matched (Old) controls (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Summary of data from all mice studied (mean +/− SEM).

| Parameter | Old 2-yr | Young 6-wk | ApoE−/−2-yr |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| Body weight g | 36.5 +/− 0.8 | 19.7 +/− 0.3** | 30.3 +/− 0.7** |

| Baseline (1% isoflurane) | |||

| HR bpm | 460 +/− 17.2 | 450 +/− 4.6 | 460 +/− 12.8 |

| Vel cm/s | 24.8 +/− 1.6 | 35.4 +/− 1.4** | 51.7 +/− 6.4* |

| Hyperemic (2.5% isoflurane) | |||

| HR bpm | 479 +/− 36 | 514 +/− 12 | 482 +/− 14 |

| Vel cm/s | 86.5 +/− 1.9 | 83.5 +/− 1.3 | 120 +/− 16.9 |

| Ratios | |||

| H/B HR | 1.05 +/− 0.04 | 1.14 +/− 0.02 | 1.05 +/− 0.02 |

| H/B Vel | 3.6 +/− 0.2 | 2.4 +/− 0.1** | 2.5 +/− 0.2** |

HR heart rate, Vel Velocity, H/B Hyperemic/Baseline,

P<0.01 versus Old,

P<0.001 versus Old.

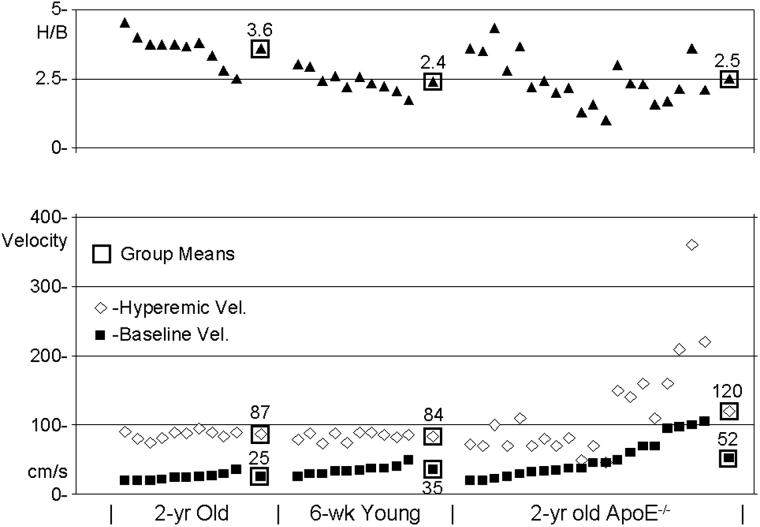

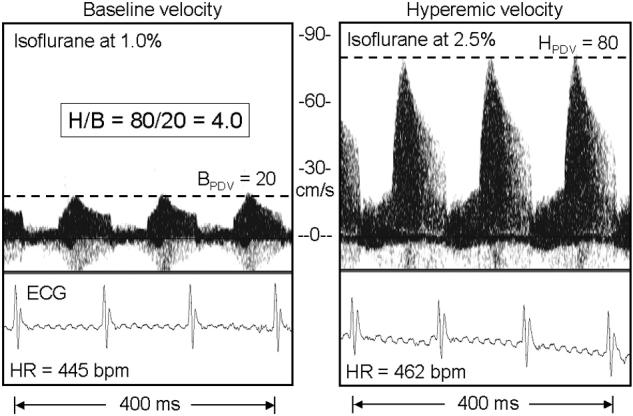

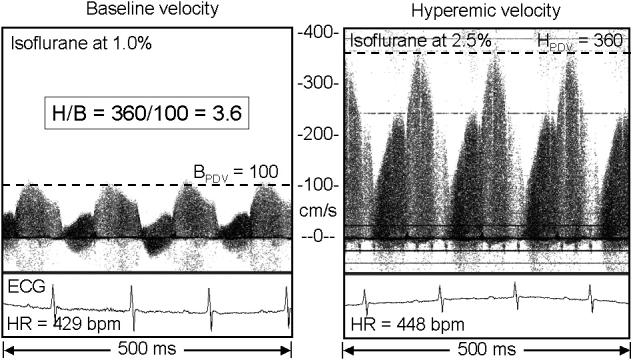

Figure 3 shows typical ECG and coronary velocity signals at baseline and during isoflurane induced hyperemia from an Old mouse, and Figure 4 shows similar signals from the ApoE−/− mouse which had the highest hyperemic (360 cm/s) and baseline (100 cm/s) coronary velocities. The dotted lines in each panel show how peak diastolic velocity (PDV) was determined from the spectral display at each level of flow. Figure 5 shows baseline, hyperemic, and H/B values sorted by baseline velocity for all of the mice studied with the group means enclosed in squares. The baseline and hyperemic velocities in the young and old mice are tightly grouped while those in the ApoE−/− mice are much more heterogeneous.

Figure 3.

Coronary Doppler signals from an Old mouse at low (1%) and high (2.5%) levels of isoflurane gas. The horizontal lines show the average of the peak diastolic velocity (PDV) at baseline or during hyperemia in each panel. The H/B is 4.0 in this mouse.

Figure 4.

Coronary Doppler signals from an ApoE−/− mouse with a presumed stenosis (estimated to be 75% by area) of the left main coronary artery, but with a relatively normal H/B of 3.6 showing the velocity extremes observed in this study.

Figure 5.

Scatter plot showing baseline, hyperemic, and H/B in all of the Old, Young, and ApoE−/− mice studied. In each group mice are sorted by baseline velocity.

Discussion

In this report we introduced a simple and noninvasive method based on Doppler ultrasound to measure coronary flow velocity in mice under baseline (B) and hyperemic (H) conditions created by changing the concentration of isoflurane gas and documented differences due to age and atherosclerosis. The ratio of hyperemic to baseline velocity (H/B) is lower in six-week old mice than in two-year old mice and is lower in two-year old ApoE−/− mice than in two-year old wild-type mice. We were able to obtain adequate coronary velocity signals in all mice, and the average time to complete a study was less than 35 minutes per animal.

Acquiring Coronary Velocity Signals

Location of the sample volume

In this study left coronary velocity signals were obtained without image guidance. Determining the location of the Doppler sample is more difficult in the absence of imaging, but knowledge of the anatomy and other clues can overcome this. In mice the origin of the left main coronary artery is nearly horizontal and lateral such that the sound beam from the Doppler probe as positioned in Figure 1 is nearly parallel to the direction of flow. In adjusting the probe and sample volume positions, we would locate the aorta, set the sample volume 0.5 to 1.0 mm closer, and then locate and maximize the coronary velocity signal. This procedure ensured a sample volume location close to the origin of the left coronary artery in normal mice and at any lesion of the proximal left main or circumflex coronary artery in the ApoE−/− mice. The small variation in hyperemic velocities in the Young and Old mice (range: 73 to 95 cm/s) suggests that the sample volume was in a consistent position in all of these mice. In addition, the proximal left main coronary artery near its attachment to the aorta undergoes less motion during the cardiac cycle than more distal segments, and this is another reason for choosing the proximal segment for these studies.

Identification of coronary flow

The waveform of epicardial coronary arterial flow in humans and other animals has a characteristic shape and timing which is easy to recognize, and the same is true in mice as illustrated in Figure 2. Coronary flow starts up when aortic flow ceases, reaches a peak of 25-50 cm/s in early diastole, and then decays. At the start of isovolumic contraction, flow drops to nearly zero followed by a significantly lower systolic component. However, because of cardiac motion, the systolic part is not always clearly visible on the spectral display (Voci et al., 2004).

Angle correction

When acquiring Doppler signals from an imaging probe, it is usually not possible to achieve an ideal Doppler angle, and a correction must be made when estimating flow velocity from the Doppler frequency. With a Doppler angle of 60 degrees a 5 degree uncertainty would produce an error of 15% in the estimation of velocity. However, the Doppler-only probe used in the present study is significantly smaller and could easily be oriented to align the sound beam nearly parallel to the vessel. When the Doppler angle is close to zero, an uncertainty of +/−15 degrees produces only a 3.5% under-estimation of true velocity. Thus, the values presented here for peak diastolic coronary velocity should be minimally affected by uncertainties in the Doppler angle. Furthermore, there would be no effect of orientation on the H/B ratio.

Factors Affecting Baseline and Hyperemic Velocities

Differences in body weight

There were significant differences in body weights among the Young (19.7 +/− 0.3 g), Old (36.5 +/− 0.8 g) and ApoE−/− (30.3 +/− 0.7 g) mice, and thus heart weights and coronary volume flows were expected to be different. Scaling laws predict that heart weight scales in direct proportion to body weight, that regional blood flow and cardiac output scale with body weight to the 3/4 power, but that blood velocity in a given vessel is independent of body weight (Dawson, 1991). Indeed, maximum hyperemic velocity is similar in the Young (83.5 +/− 1.3) and Old (86.5 +/− 1.9) groups despite the nearly 2/1 difference in body weights, and the blood velocities in most vessels in mice (see Figure 2) are similar to those in man despite the 2500/1 difference in body weights. Thus, in “normal” mice (and other animals), blood velocity does not require normalization for differences in body weight.

Use of maximum diastolic coronary velocity

When measuring coronary blood flow velocity in mice using Doppler ultrasound, the sample volume (∼ 300 um) is slightly larger than the vessel (∼200 um). Even so, the motion of the coronary artery during the cardiac cycle causes modulation of the amplitude such that parts of the waveform often appear weaker than others on the spectral display. This modulation can be seen in the signals shown in Figures 3 and 4. The part which is weak depends on the positioning of the probe and the sample volume, and we tried to set the sample volume to obtain the strongest signal during the peak of coronary flow in early diastole. The amplitude modulation and low frequency Doppler signals due to cardiac motion sometimes made it difficult to display a complete waveform of coronary flow throughout the cardiac cycle. Thus, in this report we used the peak coronary velocity in early diastole assuming that the temporal peak velocity is proportional to the temporal mean velocity taken over the cardiac cycle. This assumption has been validated in man (Saraste et al., 2001), and the use of peak diastolic velocity in place of average diastolic velocity in the estimation of coronary reserve is becoming more common and accepted in clinical studies because maximum velocity is more robust, easier to measure, and less affected by noise, cardiac motion, and flow in neighboring vessels (Cicala et al., 2004; Galderisi et al., 2003; Galderisi et al., 2004; Rigo, 2005; Santagata et al., 2005; Saraste et al., 2001). In the studies reported here we did not see significant changes between baseline and hyperemia in the waveform of coronary velocity or in the ratio of systolic to diastolic velocity. However, under conditions where the ratio of systolic to diastolic velocity is altered or where an intervention changes the ratio, the use of peak diastolic coronary velocity as an index of mean coronary velocity would not be appropriate.

In most systemic arteries, there are significant changes in the velocity waveform and its pulsatility when flow is increased by exercise or by vasodilation such that changes in peak velocity cannot be used to estimate changes in mean velocity. In general, diastolic velocity is increased and pulsatility is decreased with vasodilation, but this does not appear to be the case for coronary artery flow. The epicardial compliance vessels in the coronary circulation are relatively short such that the waveform of coronary flow is dominated by the modulation of peripheral resistance by cardiac contraction rather than by the interaction of complex vascular impedance and wave reflections from the periphery. For example, the systolic component of coronary velocity in the old mouse illustrated in Figure 3 is small and is not significantly changed during hyperemia. The systolic component in the ApoE−/− mouse illustrated in Figure 4 is much larger, but the percentage change with hyperemia is only slightly higher than that of the diastolic component.

Isoflurane as a coronary vasodilator

The coronary vasodilator properties of isoflurane are well-known by anesthesiologists (Reiz et al., 1983). The coronary vasodilation is thought to be mediated by ATP dependent K+ channels that are antagonized by glibencamide but not by adenosine antagonists (Zhou et al., 1998). It is also known that anesthetics can have differential effects on hemodynamics by mouse strain (Zuurbier et al., 2002). Whether there are age-related changes in these receptors or in their sensitivity is uncertain. Our data show significant differences in baseline velocities at low concentrations of isoflurane between Young and Old mice but not in hyperemic velocities at higher concentrations of isoflurane. One interpretation is that the receptors may have different sensitivities at low concentrations but become similarly saturated at higher concentrations of isoflurane.

It has been shown in dogs that the isoflurane induced coronary vasodilation is both dose and step-size dependent such that a gradual increase in isoflurane has a smaller effect than a sudden large increase (Crystal et al., 1995; Zhou et al., 1998). In the present study we employed large steps, going between 1% and 2.5% to maximize the effect on coronary flow. In dogs the increase in coronary blood flow to step changes in isoflurane was estimated to be about 80% of the level attained by adenosine. The H/B levels we measured in mice are similar to those reported by others in mice using adenosine in isolated hearts (1.4 - 4.0) (Bratkovsky et al., 2004; Flood and Headrick, 2001; Talukder et al., 2002) and are higher than those reported by Wikstrom, et al. (2005) using adenosine in live mice (1.94). The lower values for H/B reported by Wikstrom could be due to an increased baseline flow caused by the use of isoflurane at concentrations of 0.7% to 1.5% as an anesthetic.

We cannot rule out the possibility that isoflurane alters the diameter of left main coronary artery such that the relationship between flow and velocity is a function of concentration. Kober, et al. (2005) used isoflurane as a vasodilator to study regional myocardial perfusion in mice using MRI and reported an average hyperemic/baseline ratio of 2.45 obtained by increasing the isoflurane concentration from 1.25% to 2.00% in 10-26 week old mice. This value based on perfusion is similar to our average value of 2.4 based on velocity in the Young mice. Thus, although isoflurane may not be a maximal coronary vasodilator, its effect on flow and velocity appears to be similar.

Baseline Velocity

In estimating coronary reserve it is extremely important to obtain a true minimum level of baseline velocity. Hyperemic velocity was much more consistent (73 to 95 cm/s) and easier to obtain at the higher doses of isoflurane (2-3%), while baseline velocity was more variable (20 to 49 cm/s). The sensitivity of H/B to baseline velocity illustrates the importance in establishing a true and consistent level. The lowest coronary velocity occurred at the lowest level of isoflurane (0.5 - 1.0%), but when the mouse started to wake up and become more aroused, coronary velocity increased significantly. In this study we used 1% as the consistent level to establish baseline coronary velocity without arousal or movement, but experimental conditions and differential sensitivity to isoflurane could have altered the baseline level and thus the estimated flow reserve (H/B).

Effect of Local Stenosis

It has been suggested that the estimation of coronary reserve in patients by H/B is questionable in the presence of a local stenosis which elevates baseline velocity (Voci et al., 2004). This is attributed, in part, to the limited range-velocity product of pulsed Doppler velocimeters (aliasing), to the difficulty in correcting for angle in the presence of disturbed and non-axial flow (Tortoli et al., 2003), and to alterations in the velocity profile (Nichols and O'Rourke, 1998). However, as shown in Figure 4, the alias limit of 4.5 m/s was never exceeded in our experiments with mice, and the use of a Doppler angle close to zero would have minimized any potential errors due to disturbed flow and non-axial velocities (Li et al., 2003). We cannot rule out changes in the velocity profile at high versus low flow in the region of the stenosis which would alter the relationship between the measured peak velocity and the luminal average velocity or volume flow.

H/B in mice versus man

Coronary flow reserve has been estimated in man during surgery (Marcus et al., 1981), in the cardiac catheterization laboratory (White et al., 1984; Wilson et al., 1985), and most recently in the echocardiography laboratory (Saraste et al., 2001; Voci et al., 2004) using the ratio of hyperemic to baseline flow velocity. The reported values are between 2.5 and 5.0 depending on the flow or velocity sensing method, the vasodilator, and the experimental or clinical conditions. The values we obtained from mice using noninvasive Doppler ultrasound are between 1.2 and 4.6 in the normal mice and are comparable to the reported values from man. This suggests that the ratio of hyperemic to baseline coronary velocity in response to high and low levels of isoflurane may be valid index of coronary flow reserve in mice.

Higher H/B in Old mice

In man H/B is used to estimate the severity and significance of several cardiac pathologies including coronary artery disease which reduces hyperemic flow (Gould et al., 1974; Marcus et al., 1981; Marcus, 1983), and valvular disease which increases resting cardiac work and baseline flow (Marcus et al., 1982). Wieneke, et al. (2006) studied several factors which might influence H/B in man and found that only age and baseline velocity influenced H/B in healthy individuals. It has also been shown in man that therapy which decreases cardiac work such as aortic valve replacement (Hildick-Smith and Shapiro, 2000) reduces baseline coronary flow velocity and increases H/B. In rats H/B was found to be higher in old versus young rats because of decreased baseline flow velocity (Kristo et al., 2005). Our findings in mice are in substantial agreement with the findings in rats and in man that age and baseline velocity are the major factors determining H/B in the absence of coronary stenoses. Conditions which increase baseline cardiac work such as pressure (Rockman et al., 1993) or volume (Hartley et al., 2000) overload would be expected to decrease coronary reserve in mice as they do in man (Marcus et al., 1982). However, it remains unclear whether the lower baseline velocity in Old versus Young mice is due to reduced demand at rest or to differential sensitivity to isoflurane.

Lower H/B and higher variation in ApoE−/−mice

The baseline and hyperemic velocities in response to isoflurane concentration were tightly grouped in the Young and Old mice with most of the variation being in the level of baseline velocity as shown by the trends in Figure 5. In these healthy mice H/B was highly correlated with baseline velocity (R2 = 0.93) and poorly correlated with hyperemic velocity (R2 = 0.005). However, in the ApoE−/− mice, the scatter in the levels of baseline and hyperemic velocities was much greater, and the hyperemic velocity was more correlated with baseline velocity (R2 = 0.66) than was H/B with baseline velocity (R2 = 0.03). This suggests that the stenoses are governing hyperemic velocity in the ApoE−/− mice more than baseline or hyperemic coronary volume flow. However, the poor relationship between H/B and baseline velocity in the ApoE−/− mice suggests that the stenoses (which elevate both baseline and hyperemic velocities) are not flow-limiting. In one ApoE−/− mouse (Figure 4) with a H/B of 3.6, the baseline velocity was 100 cm/s and the hyperemic velocity was 360 cm/s. Both baseline and hyperemic velocities are about 4 times the normal values in old mice suggesting a stenosis of 75% based on area or 50% based on diameter and which had a minimal effect on volume flow reserve. Indeed, Gould et al. (1974) have shown that baseline coronary volume flow is usually normal until the diameter reduction exceeds 80 to 85%, and that it requires a diameter reduction exceeding 50% to reduce hyperemic flow after vasodilation. Thus, the most likely explanation for the high variability in baseline velocity, hyperemic velocity, and H/B in the ApoE−/− mice is the presence of coronary artery disease and stenoses in the left coronary arteries of many of the mice (Nakashima et al., 1994; Paigen et al., 1987).

Conclusions

We conclude that coronary flow velocity can be measured noninvasively in mice with Doppler ultrasound and that isoflurane gas can be used as a convenient and noninvasive coronary vasodilator. Our data suggest that the ratio of hyperemic to baseline coronary blood velocity can be a valuable index of coronary reserve despite the fact that isoflurane may not be a maximal coronary vasodilator. The differences noted in the ratio of hyperemic to baseline coronary blood velocity in Young, Old, and ApoE−/− mice are consistent with differences in baseline cardiac work, differential sensitivity to low levels of isoflurane, and/or to the presence of stenotic coronary lesions. Therefore, caution must be used in estimating coronary reserve using an agent such as isoflurane which may not be a maximal vasodilator and which may also alter resting flow. In addition, investigators who use isoflurane as an anesthetic agent in cardiovascular studies in mice and other animals need to consider its potent and dose-dependent coronary vasodilator properties in interpreting results.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Dr. Y-X Wang of Berlex Biosciences for supplying the ApoE−/− and age-matched old mice, Thuy Pham and Jennifer Pocius for technical assistance, and James Brooks for editorial assistance.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-HL22512, P01-HL42550, R01-AG17899, R41-HL76928, and K25-HL73041.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Bernard J-M, Doursout M-F, Wouters PF, Hartley CJ, Merin RG, Chelly JE. Effects of sevoflurane and isoflurane on hepatic circulation in the chronically instrumented dog. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:541–545. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199209000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratkovsky S, Aasum E, Birkeland CH, Riemersma RA, Myhre ESP, Larson TS. Measurement of coronary flow reserve in isolated hearts from mice. Acta Physiol Scand. 2004;181:167–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicala S, Galderisi M, Guarini P, D'Errico A, Innelli P, Pardo M, Scognamiglio G, de Divitiis O. Transthoracic coronary flow reserve and dobutamine derived myocardial function: a 6-month evaluation after successful coronary angioplasty. Cardiovascular Ultrasound. 2004;2:26–35. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JS, Hartley CJ. The pulsed Doppler coronary artery catheter: Preliminary report of a new technique for measuring rapid changes in coronary artery flow velocity in man. Circulation. 1977;56:18–25. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal GJ. Vasomotor effects of isoflurane in the coronary circulation. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:1516–1517. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199606000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal GJ, Czinn EA, Silver JM, Ramez SM. Coronary vasodilation by isoflurane: Abrupt versus gradual administration. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:542–549. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199502000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson TH. Engineering design of the cardiovascular system of mammals. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Flood A, Headrick JP. Functional characterization of coronary vascular adenosine receptors in the mouse. Br.J.Pharmacol. 2001;133:1063–1072. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galderisi M, Cicala S, D'Errico A, de Divitiis O, de Simone G. Nebivolol improves coronary flow reserve in hypertensive patients without coronary heart disease. J.Hypertens. 2004;22:2201–2208. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200411000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galderisi M, de Simone G, Cicala S, de Simone L, D'Errico A, Caso P, de Divitiis O. Coronary flow reserve in hypertensive patients with appropriate or inappropriate left ventricular mass. J.Hypertens. 2003;21:2183–2188. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200311000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamperi AK, Hein TW, Kuo L, Cason BA. Isoflurane-induced dilation of porcine coronary microvessels is endothelium dependent and inhibited by glibenclamide. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1465–1471. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200206000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan LM, Wikstrom J, Bergstrom G, Wandt B. Non-invasive imaging of coronary arteries using high-resolution echocardiography. Scand.Cardiovasc.J. 2005;38:121–126. doi: 10.1080/14017430410029680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould LK, Lipscomb K, Hamilton GW. Physiologic basis for assessing critical coronary stenosis: Instantaneous flow response and regional distribution during coronary hyperemia as measures of coronary flow reserve. Am.J.Cardiol. 1974;33:87–94. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(74)90743-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley CJ, Cole JS. An ultrasonic pulsed doppler system for measuring blood flow in small vessels. J.Appl.Physiol. 1974;37:626–629. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.4.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley CJ, Hanley HG, Lewis RM, Cole JS. Synchronized pulsed Doppler blood flow and ultrasonic dimension measurement in conscious dogs. Ultrasound in Med.& Biol. 1978;4:99–110. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(78)90035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley CJ, Reddy AK, Madala S, Martin-McNulty B, Vergona R, Sullivan ME, HalksMiller M, Taffet GE, Michael LH, Entman ML, Wang YX. Hemodynamic changes in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Am.J.Physiol.Heart Circ.Physiol. 2000;279:H2326–H2334. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.5.H2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley CJ, Taffet GE, Reddy AK, Entman ML, Michael LH. Noninvasive cardiovascular phenotyping in mice. ILAR Journal. 2002;43:147–158. doi: 10.1093/ilar.43.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildick-Smith DJR, Shapiro LM. Coronary flow reserve improves after aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis: An adenosine transthoracic echocardiographc study. J.Am.Coll.Cardiol. 2000;36:1889–1896. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00947-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JIE. Maximal coronary flow and the concept of coronary vascular reserve. Circulation. 1984;70:153–159. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.70.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannsen BJA, De Celle T, Debets JJM, Brouns AE, Callahan MF, Smith TL. Effects of anesthetics on systemic hemodynamics in mice. Am.J.Physiol.Heart Circ.Physiol. 2004;287:H1618–H1624. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01192.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kober F, Iltis I, Cozzone PJ, Bernard M. Myocardial blood flow mapping in mice using high-resolution spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging: Influence of ketamine/xylazine aand isoflurane anesthesia. Magn.Reson.Med. 2005;53:601–606. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristo G, Yoshimura Y, Keith BJ, Mentzer RM, Lasley RD. Aged rat myocardium exhibits normal adenosine receptor-mediated bradycardia and coronary vasodilation but increased adenosine agonist-mediated cardioprotection. J.Gerontol Biol Sci. 2005;60A:1399–1404. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.11.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y-H, Reddy AK, Taffet GE, Michael LH, Entman ML, Hartley CJ. Doppler evaluation of peripheral vascular adaptations to transverse aortic banding in mice. Ultrasound in Med.& Biol. 2003;29:1281–1289. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(03)00986-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus ML. The coronary circulation in health and disease. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus ML, Doty DB, Hiratzka LF, Wright CB, Eastham CL. Decreased coronary reserve: a mechanism for angina pectoris in patients with aortic stenosis and normal coronary arteries. N.Engl.J.Med. 1982;307:1362–1366. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198211253072202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus ML, Wright CB, Doty DB, Eastham CL, Laughlin DE, Krumm P, Fastenow C, Brody MJ. Measurement of coronary velocity and reactive hyperemia in the coronary circulation of humans. Circ.Res. 1981;49:877–891. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima Y, Plump AS, Raines EW, Breslow JL, Ross R. ApoE-deficient mice develop lesions of all phases of atherosclerosis throughout the arterial tree. Arterioscler.Thromb. 1994;14:133–140. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neishi Y, Akasaka T, Tsukiji M, Kume T, Wada N, Watanabe N, Kawamoto T, Kaji S, Yoshida K. Reduced coronary flow reserve in patients with congenstive heart failure assessed by transthoracic Doppler echocardiography. J.Am.Soc.Echocard. 2005;18:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols WW, O'Rourke MF. McDonald's Blood Flow in Arteries: Theoretical, Experimental, and Clinical Principles. Edward Arnold; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Niebauer J, Maxwell AJ, Lin PS, Tsao PS, Kosek J, Bernstein D, Cooke JP. Impaired aerobic capacity in hypercholesterolemic mice: partial reversal by exercise training. Am.J.Physiol.Heart Circ.Physiol. 1999;276:H1346–H1354. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.4.H1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paigen B, Morrow A, Holmes PA, Mitchell D, Williams RA. Quantitative assessment of atherosclerotic lesions in mice. Atherosclerosis. 1987;68:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(87)90202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plump AS, Smith JD, Hayek T, Aalto-Setala K, Walsh A, Verstuyft J, Rubin EM, Breslow JL. Severe hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice created by homologous recombination in ES cells. Cell. 1992;71:343–353. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90362-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy AK, Jones AD, Martino C, Caro WA, Madala S, Hartley CJ. Pulsed Doppler signal processing for use in mice: design and evaluation. IEEE Trans.Biomed.Eng. 2005a;52:1764–1770. doi: 10.1109/tbme.2005.855710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy AK, Taffet GE, Li Y-H, Lim S-W, Pham TT, Pocius J, Entman ML, Michael LH, Hartley CJ. Pulsed Doppler signal processing for use in mice: Applications. IEEE Trans.Biomed.Eng. 2005b;52:1771–1783. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2005.855709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiz S, Balfors E, Sorensen MB, Ariola S, Friedman A, Truedsson H. Isoflurane - a powerful coronary vasodilator in patients with coronary artery disease. Anesthesiology. 1983;59:91–97. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198308000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigo F. Coronary flow reserve in stress-echo lab. From pathophysiologic toy to diagnostic tool. Cardiovascular Ultrasound. 2005;3:8–19. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockman HA, Knowlton KU, Ross J, Jr., Chien KR. In vivo murine cardiac hypertrophy: a novel model to identify genetic signaling mechanisms that activate an adaptive physiological response. Circulation. 1993;87(Suppl VII):VII-14–VII-21. [Google Scholar]

- Santagata P, Rigo F, Gherardi S, Pratali L, Drozdz J, Varga A, Picano E. Clinical and functional determinants of coronary flow reserve in non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: An echocardiographic study. Int.J.Cardiol. 2005;105:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraste M, Koskenvuo JW, Knuuti J, Toikka JO, Laine H, Niemi P, Sakuma H, Hartiala JJ. Coronary flow reserve: measurement with transthoracic Doppler echocardiography is reproducible and comparable with positron emission tomography. Clin.Physiol. 2001;21:114–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.2001.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley DH, Millar HD, Hartley CJ, Whitlow PL. Subselective measurement of coronary blood flow velocity using a steerable Doppler catheter. J.Am.Coll.Cardiol. 1986;8:1332–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talukder MAH, Morrison RR, Mustafa SJ. Comparison of the vascular effects of adenosine in isolated mouse heart and aorta. Am.J.Physiol.Heart Circ.Physiol. 2002;282:H49–H57. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2002.282.1.H49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortoli P, Michelassi V, Bambi G, Guidi F, Righi D. Interaction between secondary velocities, flow pulsation, and vessel morphology in the common carotid artery. Ultrasound in Med.& Biol. 2003;29:407–415. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voci P, Pizzuto F, Romeo F. Coronary flow: a new asses for the echo lab. Eur.Heart J. 2004;25:1867–1879. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YX. Cardiovascular functional phenotypes and pharmacological responses in apolipoproteinE deficient mice. Neurobiol.Aging. 2005;26:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CW, Wright CB, Doty DB, Hiratza LF, Eastham CL, Harrison DG, Marcus ML. Does visual interpretation of the coronary arteriogram predict the physiological importance of a coronary stenosis? N.Engl.J.Med. 1984;310:819–824. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198403293101304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieneke H, Haude M, Ge J, Altmann C, Kaiser S, Baumgart D, von Birgelen C, Welge D, Erbel R. Corrected coronary flow velocity reserve: A new concept for assessing coronary perfusion. J.Am.Coll.Cardiol. 2006;35:1713–1720. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00639-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikstrom J, Gronros J, Bergstrom G, Gan LM. Functional and morphologic imaging of coronary atherosclerosis in living mice using high-resolution color Doppler echocardiography and ultrasound biomicroscopy. J.A.C.C. 2005;46:720–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RF, Laughlin DE, Chilian WM, Holida H, Hartley CJ, Armstrong ML, Marcus ML, White CW. Transluminal, subselective measurement of coronary artery blood flow velocity and vasodilator reserve in man. Circulation. 1985;72:82–92. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Abboud W, Manabat NC, Salem MR, Crystal GJ. Isoflurane-induced dilation of porcine coronary arterioles is mediated by ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:182–189. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199807000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y-Q, Foster FS, Nieman BJ, Davidson L, Chen XJ, Henkelman M. Comprehensive transthoracic cardiac imaging in mice using ultrasound biomicroscopy with anatomical confirmation by magnetic resonance imaging. Physiol Genomics. 2004;18:232–244. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00026.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuurbier CJ, Emons VM, Ince C. Hemodynamics of anesthetized ventilated mouse models: aspects of anesthetics, fluid support, and strain. Am.J.Physiol.Heart Circ.Physiol. 2002;282:H2099–H2105. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01002.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]