Abstract

Posttranslational modifications of proteins by small ubiquitin-like modifiers (SUMOs) regulate protein degradation and localization, protein–protein interaction, and transcriptional activity. SUMO E3 ligase functions are executed by SIZ1/SIZ2 and Mms21 in yeast, the PIAS family members RanBP2, and Pc2 in human. The Arabidopsis thaliana genome contains only one gene, SIZ1, that is orthologous to the yeast SIZ1/SIZ2. Here, we show that Arabidopsis SIZ1 is expressed in all plant tissues. Compared with the wild type, the null mutant siz1-3 is smaller in stature because of reduced expression of genes involved in brassinosteroid biosynthesis and signaling. Drought stress induces the accumulation of SUMO-protein conjugates, which is in part dependent on SIZ1 but not on abscisic acid (ABA). Mutant plants of siz1-3 have significantly lower tolerance to drought stress. A genome-wide expression analysis identified ∼1700 Arabidopsis genes that are induced by drought, with SIZ1 mediating the expression of 300 of them by a pathway independent of DREB2A and ABA. SIZ1-dependent, drought-responsive genes include those encoding enzymes of the anthocyanin synthesis pathway and jasmonate response. From these results, we conclude that SIZ1 regulates Arabidopsis growth and that this SUMO E3 ligase plays a role in drought stress response likely through the regulation of gene expression.

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic cells use a variety of small polypeptides for posttranslational modification of proteins (Vierstra and Callis, 1999; Melchior, 2000; Hay, 2001; Pickart, 2001; Gill, 2004; Kerscher et al., 2006). In addition to ubiquitin, these small peptides include ubiquitin-like proteins, such as RUB1/Nedd8, SUMO, HUB, ISG15, and ATG (Hochstrasser, 2000; Dittmar et al., 2002). Whereas a major function of ubiquitin is to mark proteins for intracellular degradation, SUMO modification of proteins leads to a number of biological consequences from antagonism of ubiquitination to regulation of transcription factor activity, alteration of protein subcellular localization and changes in protein–protein interaction (Hochstrasser, 2000, 2001; Gill, 2003; Girdwood et al., 2004; Johnson, 2004; Watts, 2004).

The sumoylation pathway resembles the better-studied ubiquitination pathway. It requires the sequential action of three enzymes, E1, E2, and E3 (Kurepa et al., 2003; Colby et al., 2006). The sumoylation process begins with the activation of the SUMO C-terminal by an E1 activating enzyme, a subsequent transfer to an SUMO E2 conjugating enzyme, and then with the help of an E3 ligase, SUMO is finally conjugated to a substrate protein. Sumoylated proteins can be removed from conjugates by SUMO proteases that are responsible for SUMO recycling. Genes encoding all these components are present in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome (Vierstra and Callis, 1999; Kurepa et al., 2003; Lois et al., 2003; Murtas et al., 2003). Recent reports have revealed that the desumoylation system confers a high specificity, in contrast with the redundancy of the conjugating system (Chosed et al., 2006). Because of the emerging importance of sumoylation in plant development, some components of the sumoylation machinery, including SUMO (Lois et al., 2003; Colby et al., 2006), SCE1a (Lois et al., 2003), SIZ1 (Miura et al., 2005, 2007), and different SUMO proteases (Murtas et al., 2003; Chosed et al., 2006; Colby et al., 2006) have been investigated. Recent observations suggested that the Arabidopsis sumoylation system plays an important role in many aspects of plant developmental processes. SUMO conjugate levels increased when plants were subjected to a number of stresses, implicating sumoylation in plant stress responses (Kurepa et al., 2003; Miura et al., 2005, 2007; Yoo et al., 2006). Moreover, increased sumoylation levels have been shown to attenuate abscisic acid (ABA)-mediated growth inhibition and amplify the induction of ABA- and stress-responsive genes, e.g., RD29A (Lois et al., 2003).

So far, only two Arabidopsis mutants have been described as being altered in sumoylation (esd4, Murtas et al., 2003; siz1, Miura et al., 2005). A SUMO protease mutant, esd4, displays an early flowering phenotype and alterations in shoot development, implicating SUMO-protein conjugates in these developmental processes (Murtas et al., 2003). A key component of the sumoylation pathway is the E3 ligase, which confers substrate specificity. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that changes in SUMO E3 ligase activity would have a significant impact on processes that are regulated by sumoylation. Yeast SIZ1 (for SAP and Miz domain) and human PIAS (for Protein Inhibitor of Activated STAT) proteins have been identified as SUMO E3 ligases that catalyze sumoylation of several proteins, including septins, LEF1, and STAT1 (Johnson and Gupta, 2001; Sachdev et al., 2001; Takahashi et al., 2001; Nishida and Yasuda, 2002; Ungureanu et al., 2003). In Arabidopsis, analysis of siz1 mutants showed that SIZ1, a SUMO E3 ligase, regulates the expression of genes involved in phosphate starvation response and during the cold acclimation process (Miura et al., 2005, 2007). The transcription factors PHR1 and ICE1, which regulate part of the response of gene expression to phosphate starvation and cold stress, respectively, appear to be targets of SIZ1 (Miura et al., 2005, 2007). In addition, Yoo et al. (2006) reported that siz1 mutants have reduced basal tolerance to heat shock, although no significant differences in gene expression were detected and Lee et al. (2006) found that SIZ1 regulates salicylate-dependent innate immunity in Arabidopsis.

Sumoylation has been implicated in the regulation of many aspects of eukaryotic development (Girdwood et al., 2004; Watts, 2004). To explore the role of the sumoylation process in plant development, we functionally characterized the Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1. Here, we demonstrate that SIZ1 is expressed in almost all plant tissues. Detailed characterization of the knockout mutant siz1-3 reveals that the E3 ligase is involved in the control of cell expansion and proliferation and in responses of plants to hormone and drought stress. We also performed a comparison between the expression profile of siz1 with wild-type plants grown under control conditions and exposed to drought stress. Our results reveal that SIZ1 regulates the expression of an important set of genes under control conditions and in response to drought stress. These results indicate that SIZ1 regulates plant growth and the response to water deficit by changes in gene expression.

RESULTS

SIZ1 Is Expressed in All Plant Tissues

A major aim of our work is to study the role of SIZ1 and, therefore, sumoylation in Arabidopsis development and physiology. SIZ1 activity could be required in all plant cells or only in specific tissues/cell types. To investigate this issue, we generated transgenic plants expressing SIZ1 promoter-β-glucuronidase (GUS) fusion genes to determine SIZ1 expression profile during plant development. Because no coding sequence can be detected in 3.65 kb upstream of the SIZ1 coding sequence (from ATG of At5g60410 to ATG of At5g60400) (data obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research, http://www.tigr.org/tdb/e2k1/ath1/), we constructed three different promoter-GUS fusion genes containing 3133, 3535, and 4311 bp of 5′ sequences upstream of the SIZ1 start codon (Figure 1A). Analysis of the GUS expression pattern in different transgenic lines showed no detectable differences among the three promoters. Figure 1 shows the representative expression profile of pSIZ1-2:GUS containing 3535 bp of 5′ upstream sequences.

Figure 1.

Expression Profile of pSIZ1-GUS.

(A) Schematic diagrams of SIZ1 promoter fragments used for promoter-GUS fusions. pSIZ1-1 (3133-bp 5′ sequence), pSIZ1-2 (3535-bp 5′ sequence), and pSIZ1-3 (4311-bp 5′ sequence) were fused to a GUS open reading frame.

(B) to (J) Expression patterns of pSIZ1-2:GUS in a 3-d-old seedlings (B), lateral root (C), primary root tip (D), lateral root primordia (E), 10-d-old seedlings (F), adult leaf (G), flower (H), young silique (I), and old silique (J) (see Results for details). Bars = 1 mm, except in (C) to (E), where bars = 0.1 mm.

In 3-d-old germinating seedlings, SIZ1 was expressed in all organs except part of the hypocotyl and the basal region of the cotyledons (Figure 1B). A similar expression pattern in hypocotyl was observed in 3-week-old plants (Figure 1F). SIZ1 was not expressed, at detectable levels, in juvenile leaves and in the basal region of developing young leaves (Figure 1F). However, in developing adult leaves, SIZ1 expression was detected in leaf blades and petioles (Figures 1F and 1G). SIZ1 was strongly expressed in the root system, especially in the primary root and lateral root tips (Figures 1C and 1D). Figure 1E shows strong expression of SIZ1 in lateral root primordial, suggesting that this gene may play a role in lateral root development.

In flowers, GUS activity was observed in inflorescence stems, sepals, stamen filaments, and stigma (Figure 1H; data not shown), and only low expression levels were detected in anther and vascular tissues of petals. In young developing siliques, SIZ1 expression was mainly found in stigma and pedicel (Figure 1I), while in adult siliques, expression was present all over the carpel (Figure 1J). No GUS staining was seen in developing seeds (data not shown).

The siz1-3 Mutant Is Affected in Growth

The widespread expression of SIZ1 in many different cell types suggested that the SUMO E3 ligase, and therefore the sumoylation system, may be involved in many different aspects of growth and development. To investigate this point further, we characterized the T-DNA knockout mutant siz1-3 (Miura et al., 2005). As a control, we generated a complementation line by transforming siz1-3 with a construct containing the SIZ1 gene under the control of the constitutive promoter 35S (siz1+35S-SIZ1, named C-siz1-3). Analysis of mRNA and protein levels in this line revealed that plants of C-siz1-3 expressed SIZ1 mRNA and protein at a slightly lower level than wild-type plants (Figures 2A and 2B).

Figure 2.

Functional Characterization of SIZ1.

(A) RNA gel blot analysis of SIZ1. Two-week-old wild-type, siz1-3, and C-siz1-3 plants were used. rRNAs in the bottom panel were used as loading controls.

(B) Protein gel blot analysis of SIZ1 using affinity-purified anti-SIZ1 antibodies. Two week-old wild-type, siz1-3, and C-siz1-3 plants were used. LS, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) large subunit.

(C) One-week-old (panels a to c), 5-week-old (d), and 8-week-old (e) wild-type, siz1-3, and C-siz1-3 plants. Bars =10 mm in (a) to (c) and 3 cm in (d) and (e).

(D) Leaf lamina length, width, and area in 25-d-old wild-type and siz1-3 mutant plants. Data are average values ± sd (n = 12).

(E) Analysis of epidermal (a) and mesophyll (b) cells of the 5th leaf of 25-d-old siz1-3 and wild-type plants by scanning electron microscopy. In a 160,000-μm2 area, a siz1-3 leaf contains 114 ± 16.7 epidermal cells and 45 ± 5.6 stomata, whereas a wild-type leaf contains 47.9 ± 5.8 epidermal cells and 17.4 ± 2.8 stomata (n = 6). Note that the mesophyll cell size of siz1-3 leaf is smaller than that of the wild type. Bars = 100 μm.

(F) Anthocyanin contents of wild-type, siz1-3, and C-siz1-3 plants. Error bars represent sd (n = 3). Data are shown as relative units. FW, fresh weight.

(G) RNA gel blot analysis of total RNAs (10 μg) from 5-week-old wild-type, siz1-3, and C-siz1-3 plants using specific probes for CHS1, CHI, and PAL1. rRNAs in the bottom panel were used as loading controls.

One week after germination on Murashige and Skoog (MS) plates, siz1-3 plants showed no visible difference when compared with wild-type plants (data not shown). However, when germinated on soil, siz1-3 was significantly smaller than both the wild type and C-siz1-3 (Figure 2C). As juvenile leaves began to develop, siz1-3 exhibited deficiencies in leaf elongation and enlargement (Figure 2C, panels a to c), and these differences were clearly manifested in rosette leaves of 5-week-old plants (Figure 2C, panel d). Similar differences could be seen in 25-d-old plants grown in vitro (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). In addition, 8-week-old siz1-3 plants were significantly shorter compared with wild-type and C-siz1-3 plants (Figure 2C, panel e). Compared with wild-type leaves, siz1-3 leaves were reduced in length and width by approximately twofold (Figure 2D), and as a consequence, there was a 4.5-fold reduction in total leaf area (Figure 2D). Microscopy analysis revealed that siz1-3 leaves contained smaller epidermal and mesophyll cells when compared with wild-type leaves (Figure 2E). In a 160,000-μm2 area, the siz1-3 leaf contained 114 ± 16.7 epidermal cells and 45 ± 5.6 stomata, whereas a wild-type leaf contained 47.9 ± 5.8 epidermal cells and 17.4 ± 2.8 stomata. Therefore, siz1 leaves had ∼2.3 times more cells per unit area than wild-type leaves. Wild-type leaf phenotype was recovered in C-siz1-3, attributing these mutant phenotypes to a deficiency in SIZ1. These results indicate that SIZ1, and therefore the sumoylation process, plays an important role in Arabidopsis cell expansion and proliferation.

SIZ1 Regulates Anthocyanin Accumulation

Visual observation of siz1-3 indicated reduced anthocyanin accumulation in petioles of adult plants when compared with the wild type and C-siz1-3 (Figure 2C, panel d). We compared anthocyanin content of 5-week-old plants of the wild type, siz1-3, and C-siz1-3 grown under control conditions. Figure 2F shows that siz1-3 plants accumulated significantly lower anthocyanin levels than the wild type and C-siz1-3. The anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway is catalyzed by several enzymes, including PAL1, CHS1, and CHI (Solfanelli et al., 2006). RNA gel blot analysis revealed that, whereas the expression of PAL1 and CHI was not significantly changed in siz1-3, the CHS1 transcript accumulation was clearly lower in the mutant compared with the wild type (Figure 2G). Moreover, the reduced CHS1 transcript in siz1-3 was restored to wild-type levels in C-siz1-3 plants. These results provide evidence that SIZ1 regulates the synthesis of anthocyanin by regulating CHS1 expression.

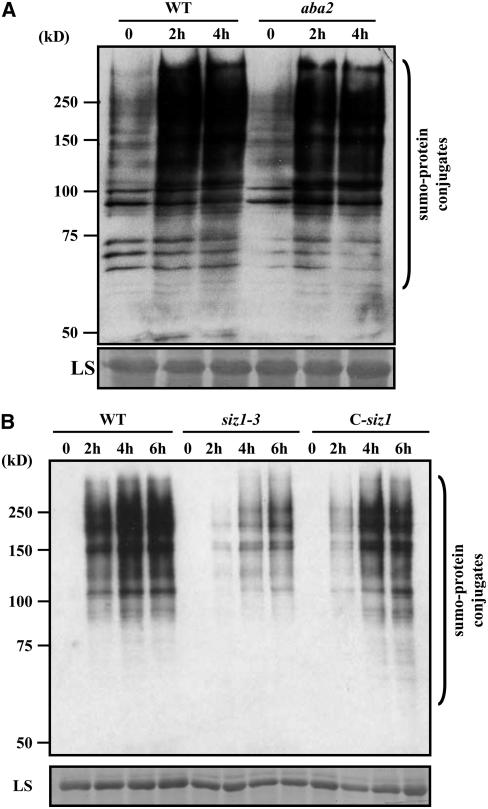

Accumulation of SUMO-Protein Conjugates in Response to Drought Stress

Abiotic stresses, such as heat shock, low temperatures, ethanol, and H2O2 and phosphorus deficiency, have been reported to trigger a significant increase in SUMO-protein conjugate levels (Kurepa et al., 2003; Murtas et al., 2003; Yoo et al., 2006; Miura et al., 2007). Figure 3A shows that SUMO-protein conjugate levels were also elevated by drought treatment. This induction appeared to be ABA independent because no significant difference was observed between wild-type and the ABA-deficient mutant aba2 (Figure 3A). To explore the possible role of SIZ1 in this process, we compared changes in SUMO-protein conjugate levels in the wild type, siz1-3, and C-siz1-3. Drought-induced accumulation of SUMO-protein conjugates was reduced in siz1-3 but restored to near wild-type levels in C-siz1-3 (Figure 3B), suggesting that SIZ1 mediates, in part, the increase of SUMO-protein conjugate levels in response to drought stress.

Figure 3.

Accumulation of SUMO-Protein Conjugates Induced by Dehydration Is Partially Dependent on SIZ1.

Protein extracts were analyzed by protein gel blots using anti-SUM1 polyclonal antibodies to detect SUMO-protein conjugates. The large subunit (LS) of Rubisco (55 kD) was used as a loading control. Each lane contained 10 μg of protein.

(A) Three-week-old wild-type and aba2 mutant plants exposed to drought for 0, 2, and 4 h.

(B) Three-week-old wild-type, siz1-3, and C-siz1-3 plants exposed to drought for 0, 2, 4, and 6 h.

SIZ1 Is a Positive Regulator of Drought Stress Tolerance

The SIZ1-dependent increase in SUMO-protein conjugate levels in response to drought suggests a possible role of this E3 ligase in the stress response. To investigate this possibility, we quantified the tolerance to drought stress of wild-type, siz1-3, and C-siz1-3 plants by measuring their loss of fresh weight and their capacity to survive 2 weeks after withholding water. Figure 4 shows that siz1-3 was significantly more sensitive to drought stress than the wild type. In the first series of experiments, siz1-3 lost 50% of fresh weight in 37 min compared with 49 min in the wild type (Figure 4A). This decreased capacity of siz1-3 to retain water was more dramatic in experiments where water was withheld from soil-grown plants for 2 weeks. Upon resumption of watering, 89% ± 5.2% of wild-type plants survived, whereas none of the siz1-3 plant recovered (Figure 4C). Moreover, plants of C-siz1-3 displayed wild-type-level tolerance to this stress with a 93% ± 3.1% survival rate (Figure 4C). To rule out the possibility that these results were affected by plant size, we also measured the loss of fresh weight of wild-type, siz1-3, and C-siz1-3 plants grown on plates. Note that in contrast with plants grown on soil, these plants have a similar size irrespective of the genotypes, and whole plants were used for these experiments. The results of these experiments confirmed that siz1-3 was more sensitive to drought stress (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). Finally, SIZ1 protein levels showed a transient increase at 2 h after drought treatment (Figure 4D) consistent with its role in mediating synthesis of SUMO-protein conjugates.

Figure 4.

SIZ1 Plays an Important Role in Drought Tolerance.

(A) Water loss quantification in percentage of fresh weight lost (0, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 60 min) in 3-week-old wild-type, siz1-3, and C-siz1-3 plants. The percentage of fresh weight (FW) remaining after the treatment was determined. Data represent average values ± sd (n = 6).

(B) Survival of plants subjected to water withholding for 3 weeks after resumption of watering for 1 week.

(C) Percentage of survival in (B). Data represent average values ± sd (n = 6).

(D) Analysis of SIZ1 protein levels in 2-week-old wild-type plants exposed to drought for 0, 2, and 4 h. Protein extracts were analyzed by protein gel blots using affinity-purified anti-SIZ1 antibodies. LS, large subunit of Rubisco.

Transcriptome Analysis of siz1-3

To study the molecular basis of siz1-3 phenotypes, we performed a genome-wide expression analysis using samples from wild-type and siz1-3 plants under normal growth conditions and after 2 h of drought stress. Under control conditions, the expression of ∼1600 Arabidopsis genes (7% of the total) was deregulated in siz1-3 (more than twofold difference relative to the wild type) (see Supplemental Table 1 online). Among them, we found 317 genes whose expression was lower in siz1-3 than in wild-type plants (see Supplemental Table 2 online). Interestingly, 11 of these genes encode proteins involved in brassinosteroid biosynthesis and the signaling pathway and four in the auxin signaling pathway (Table 1). These results indicate that under normal growth conditions, SIZ1 regulates brassinosteroid and auxin biosynthesis and signaling pathways, and through these pathways, influences Arabidopsis development. In addition, we found 643 genes that showed an increased mRNA accumulation in siz1-3 compared with wild-type plants (see Supplemental Table 3 online). This group of genes included PR-1, PR-2, and PR-5, which were previously reported to show increased expression in the mutant (Lee et al., 2006).

Table 1.

Genes Underexpressed in siz1-3 Plants under Normal Growth Conditions

| Gene Name | AGI Codea | Ratiob | P Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brassinosteroids | ||||

| CYP85A2 | AT3G30180 | 4 | 1.52E-02 | Cytochrome P450 |

| BEE1 | AT1G18400 | 4 | 8.45E-03 | Helix-loop-helix DNA binding protein |

| SQP1 | AT5G24150 | 4 | 2.48E-02 | Squalene monooxygenase |

| LUP1 | AT1G78970 | 4 | 4.43E-02 | Lupeol synthase |

| DWF4 | AT3G50660 | 3 | 1.01E-02 | 22α hydroxylase |

| SQS2 | AT4G34650 | 3 | 4.70E-02 | Squalene synthase |

| DET2 | AT2G38050 | 2 | 7.00E-03 | 3-oxo-5-α-steroid 4-dehydrogenase |

| HMG1 | AT1G76490 | 2 | 4.18E-02 | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase |

| BIM1 | AT5G08130 | 2 | 2.88E-02 | Basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family protein |

| DWF1 | AT3G19820 | 2 | 2.86E-02 | Cell elongation protein |

| FK | AT3G52940 | 2 | 4.52E-02 | Nuclear envelope membrane protein |

| Auxin | ||||

| ATR1 | AT5G60890 | 4 | 2.13E-02 | cyp450 reductase |

| IAA6 | AT1G52830 | 4 | 2.99E-02 | Auxin-responsive protein |

| PIN7 | AT1G23080 | 3 | 4.76E-02 | Auxin efflux carrier protein |

| AUX1 | AT2G38120 | 2 | 4.56E-02 | Putative transporter of amino acid–like molecules |

| ABA | ||||

| NCED3 | AT3G14440 | 5 | 3.42E-02 | 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase |

| CIPK20 | AT5G45820 | 5 | 9.17E-03 | CBL-interacting Ser/Thr protein kinase |

| ABA1 | AT5G67030 | 2 | 2.26E-02 | Zeaxanthin epoxidase |

| Light | ||||

| PIF4 | AT2G43010 | 3 | 2.40E-02 | bHLH protein |

| PKS2 | AT1G14280 | 3 | 4.45E-02 | Phytochrome kinase substrate |

| PRR5 | AT5G24470 | 2 | 2.13E-02 | Pseudo-response regulator |

| PIL6 | AT3G59060 | 2 | 4.07E-02 | Myc-related bHLH transcription factor |

AGI, Arabidopsis Genome Initiative.

Expression fold decrease in siz1-3 relative to wild-type plants.

The responses and tolerance of Arabidopsis to drought stress are to a large extent underpinned by changes in gene expression (Shinozaki et al., 2003; Sakuma et al., 2006). Therefore, it is not surprising that after 2 h of drought treatment the expression of 25% of the Arabidopsis genes was significantly altered in the wild type (see Supplemental Table 4 online). Among them, ∼1700 genes showed a significant increase in their expression levels (more than twofold induction; see Supplemental Table 5 online). In this category, we found many genes previously reported to be induced by ABA, pathogen attack, heat shock, jasmonic acid, or auxin (Table 2). In addition, drought-induced expression of ∼1044 genes was significantly deregulated in siz1-3 (see Supplemental Table 6 online). Moreover, siz1-3 seemed to be needed for the appropriate drought induction of 262 of these genes (more than twofold expression decrease in siz1-3; see Supplemental Table 7 online). Included in this category (Tables 3 and 4) were genes previously implicated in drought stress tolerance, such as MYC2 (Abe et al., 2003), ANNAT4 (Lee et al., 2004), COR15A (Li et al., 1993), KIN1 (Gilmour et al., 1992), and P5CS1 (Yoshiba et al., 1995). We found that the expression of genes coding for almost all of the anthocyanin biosynthetic enzymes were induced by drought in the wild type, and this induction was severely impaired in siz1-3 (Table 4). The same situation applies to genes involved in brassinosteroid synthesis and in jasmonate responses (Tables 3 and 4). All these genes can be divided into two categories depending in how SIZ1 affects their expression. The first category included genes whose expression was lower in siz1-3 compared with the wild type either under normal growth conditions or in response to drought stress, but these genes remained drought inducible in the mutant (Table 3). The second category included genes that were expressed at wild-type levels under normal conditions but did not respond significantly to drought stress in siz1-3 (Table 4). Taken altogether, our results demonstrate that SIZ1, and therefore sumoylation of proteins, play an important role in the regulation of several hormone signaling pathways under normal growth conditions and during responses to drought stress.

Table 2.

Drought-Inducible Genes

| Gene Name | AGI Code | P Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abiotic stress | |||

| ABF3 | AT4G34000 | 1.61E-02 | ABA-responsive element binding factor |

| ADH1 | AT1G77120 | 1.20E-02 | Alcohol dehydrogenase |

| ANNAt4 | AT2G38750 | 2.18E-02 | Calcium-dependent membrane binding protein |

| At MRP | AT1G04120 | 1.89E-02 | ABC transporter family protein |

| COR15A | AT2G42540 | 8.99E-03 | Cold-regulated protein |

| COR47 | AT4G38410 | 3.31E-03 | Cold-regulated protein |

| ERD10 | AT1G20450 | 2.54E-02 | Dehydrin |

| ERD2 | AT1G29330 | 3.37E-03 | Endoplasmic reticulum retention signal receptor |

| MYB2 | AT2G47190 | 1.79E-02 | MYB transcription factor |

| MYC2 | AT1G32640 | 8.82E-03 | Transcription factor |

| P5CS1 | AT2G39800 | 8.10E-03 | δ 1-Pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase |

| RAB18 | AT5G66400 | 9.22E-03 | Dehydrin |

| RAP2.4 | AT1G78080 | 8.18E-03 | ERF/AP2 transcription factor family |

| RAP2.6 | AT1G43160 | 1.32E-02 | ERF/AP2 transcription factor |

| RCI2B | AT3G05890 | 1.90E-02 | Low-temperature and salt-responsive protein |

| RD20 | AT2G33380 | 1.60E-03 | Calcium binding protein |

| RD29A | AT5G52310 | 1.74E-02 | Low-temperature-responsive 78-kD protein |

| RD29B | AT5G52300 | 2.85E-03 | Low-temperature-responsive 65-kD protein |

| SAL1 | AT5G63980 | 4.34E-02 | FIERY1 protein |

| SUS1 | AT5G20830 | 1.56E-03 | Sucrose synthase |

| Anthocyanin | |||

| CHS1* | AT5G13930 | 7.61E-03 | Chalcone synthase |

| DFR | AT5G42800 | 2.57E-02 | Dihydroflavonol reductase |

| F3H | AT3G51240 | 3.10E-02 | Flavanone 3-hydroxylase |

| FLS | AT5G08640 | 2.85E-02 | Flavonol synthase |

| PAP1 | AT1G56650 | 2.76E-02 | MYB domain |

| TT5 | AT3G55120 | 5.03E-03 | Chalcone-flavanone isomerase |

| TT7 | AT5G07990 | 1.86E-02 | Flavonoid 3′-monooxygenase/flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H) |

| TT8 | AT4G09820 | 7.86E-03 | bHLH protein |

| UGT78D1 | AT1G30530 | 1.94E-02 | UDP glucose:flavonoid 3-o-glucosyltransferase |

| ABA | |||

| ABF3* | AT4G34000 | 1.61E-02 | ABA-responsive element binding protein |

| ABI1* | AT4G26080 | 1.08E-03 | Protein phosphatase 2C |

| ABI2* | AT5G57050 | 6.56E-03 | Protein phosphatase 2C |

| AHG3 | AT3G11410 | 9.43E-03 | Protein phosphatase 2C |

| AtHB12* | AT3G61890 | 1.51E-02 | Homeodomain Leu zipper class I |

| AtHB7* | AT2G46680 | 9.23E-04 | Homeobox Leu zipper |

| MYB102* | AT4G21440 | 1.00E-02 | MYB transcription factor |

| ATR1* | AT4G24520 | 1.42E-03 | cyp450 reductase |

| COR13* | AT4G23600 | 3.70E-02 | Cys lyase |

| GBF3 | AT2G46270 | 1.05E-02 | bZIP G-box binding protein |

| HAB1* | AT1G72770 | 6.15E-04 | Protein phosphatase 2C |

| MYB7* | AT2G16720 | 8.57E-03 | Myb transcription factor |

| PRN | AT3G59220 | 5.00E-02 | Cupin domain–containing protein |

| Jasmonic | |||

| AOC3 | AT3G25780 | 3.33E-02 | Allene oxide cyclase |

| AOS | AT5G42650 | 5.66E-03 | Allene oxide synthase |

| DAD1 | AT2G44810 | 1.65E-03 | Chloroplastic phospholipase A1 |

| ESP | AT1G54040 | 3.85E-03 | Epithiospecifier protein |

| JAR1 | AT2G46370 | 2.44E-03 | Auxin-responsive GH3 family protein |

| JMT | AT1G19640 | 2.61E-02 | S-adenosyl-l-Met:jasmonic acid carboxyl methyltransferase |

| LOX3 | AT1G17420 | 2.85E-02 | Lipoxygenase |

| TAT3 | AT2G24850 | 2.29E-02 | Tyrosine aminotransferase |

| Auxin | |||

| CYP79B2 | AT4G39950 | 1.89E-02 | Cytochrome P450 |

| IAA5 | AT1G15580 | 2.42E-02 | Auxin-responsive protein |

| IAR3 | AT1G51760 | 3.82E-02 | IAA–amino acid conjugate hydrolase |

| ILL6 | AT1G44350 | 3.60E-02 | IAA–amino acid hydrolase |

| ILR1 | AT3G02875 | 2.71E-03 | IAA–amino acid hydrolase |

| Ethylene | |||

| ACS2* | AT1G01480 | 2.49E-02 | 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate |

| ERS2* | AT1G04310 | 3.93E-03 | Two-component His kinase |

| Brassinosteroid | |||

| SQS2 | AT4G34650 | 1.27E-02 | Squalene synthase |

| SQP1 | AT5G24150 | 2.03E-02 | Squalene monooxygenase 1,1 |

| Defense response | |||

| ASA1 | AT5G05730 | 1.14E-02 | Anthranilate synthase |

| DHS1 | AT4G39980 | 1.66E-02 | 1-Deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate |

| EDS5 | AT4G39030 | 1.95E-03 | Orphan multidrug and toxin extrusion transporter |

| MLO11 | AT5G53760 | 2.74E-03 | Seven transmembrane MLO family protein |

| PAL1* | AT2G37040 | 1.86E-02 | Phe ammonia-lyase |

| PLP7 | AT3G54950 | 3.73E-03 | Patatin-related |

| WRKY18 | AT4G31800 | 2.40E-02 | WRKY family transcription factor |

| Heat shock | |||

| HSFA2 | AT2G26150 | 1.24E-02 | Heat stress transcription factor |

| HSFA6B | AT3G22830 | 8.11E-03 | Heat stress transcription factor |

| HSP17.6-C11 | AT5G12020 | 4.71E-03 | Heat shock protein |

| HSP17.8* | AT1G07400 | 2.51E-03 | Heat shock protein |

| HSP23.5-M | AT5G51440 | 3.91E-02 | Mitochondrial small heat shock protein |

| HSP70* | AT5G02500 | 2.65E-02 | Heat shock protein |

| HSP81-1 | AT5G52640 | 1.84E-02 | Heat shock protein |

| Phosphate starvation | |||

| PLDZ2 | AT3G05630 | 1.83E-03 | Phospholipase D protein |

| Light | |||

| PIF3 | AT1G09530 | 2.05E-03 | Transcription factor |

| PTF1 | AT3G02150 | 1.60E-03 | TCP family transcription factor |

| Development | |||

| BIGPETAL | AT1G59640 | 5.36E-03 | bHLH encoding gene |

The asterisk indicates genes previously described as being stress inducible. IAA, indole-3-acetic acid.

Table 3.

Drought-Inducible Genes Underexpressed in siz1-3

| Gene Name | AGI Code | P Value | WT Ca | WT D2 hb | Ratioc | siz1Cd | siz1 D2 he | Ratiof | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | |||||||||

| ATR1 | AT5G60890 | 2.26E-03 | 38 | 1196 | 31 | 9 | 250 | 27 | Myb-like transcription factor |

| ANNAT4 | AT2G38750 | 6.09E-03 | 243 | 1323 | 5 | 37 | 186 | 5 | Calcium-dependent membrane binding protein |

| RCI2B | AT3G05890 | 2.43E-02 | 227 | 943 | 4 | 82 | 355 | 4 | Low-temperature and salt-responsive protein |

| P5CS1 | AT2G39800 | 1.50E-02 | 1264 | 4680 | 4 | 37 | 401 | 11 | δ 1-Pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase |

| MYC2 | AT1G32640 | 7.69E-03 | 1080 | 3020 | 3 | 435 | 1486 | 4 | Transcription factor |

| COR15a | AT2G42540 | 3.91E-02 | 10518 | 23450 | 2 | 964 | 3040 | 3 | Cold-regulated protein |

| KIN1 | AT5G15960 | 2.12E-02 | 21422 | 43230 | 2 | 1130 | 2912 | 3 | Cold- and ABA-inducible protein |

| Jasmonic | |||||||||

| JMT | AT1G19640 | 7.85E-03 | 18 | 864 | 46 | 6 | 333 | 54 | S-adenosyl-l-Met:jasmonic acid carboxyl methyltransferase |

| COI3 | AT4G23600 | 7.72E-04 | 3031 | 18327 | 6 | 656 | 6640 | 10 | Cys lyase |

| AOS | AT5G42650 | 1.32E-03 | 1711 | 7748 | 4 | 351 | 3304 | 9 | Allene oxide synthase |

| ESP | AT1G54040 | 8.15E-04 | 664 | 1468 | 2 | 109 | 248 | 2 | Epithiospecifier protein |

| LOX1 | AT1G55020 | 1.83E-02 | 47 | 102 | 2 | 38 | 45 | 1 | Lipoxygenase |

| Brassinosteroid | |||||||||

| SQS2 | AT5G24150 | 1.68E-03 | 33 | 162 | 5 | 12 | 31 | 3 | Squalene synthase |

| SQP1 | AT4G34650 | 1.45E-02 | 107 | 410 | 4 | 30 | 76 | 2 | Squalene monooxygenase 1,1 |

Absolute expression value of wild-type plants under normal conditions.

Absolute expression value of wild-type plants exposed for 2 h to drought stress.

Expression fold increase in wild-type dehydrated plants relative to control plants.

Absolute expression value of siz1-3 plants under normal conditions.

Absolute expression value of siz1-3 plants exposed for 2 h to drought stress.

Expression fold increase in siz1-3 dehydrated plants relative to control plants.

Table 4.

Drought-Inducible Genes with Decreased Induction by Drought in siz1-3

| Gene Name | AGI Code | P Value | WT Ca | WT D2 hb | Ratioc | siz1Cd | siz1 D2 he | Ratiof | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | |||||||||

| RD29B | AT5G52300 | 4.47E-03 | 33 | 677 | 21 | 37 | 186 | 5 | Low-temperature-responsive 65-kD protein |

| SAL1 | AT5G63980 | 8.72E-04 | 243 | 1490 | 6 | 736 | 521 | 1 | FIERY1 protein |

| Anthocyanin | |||||||||

| PAP1 | AT1G56650 | 8.96E-03 | 56 | 1341 | 24 | 31 | 320 | 10 | MYB domain–containing transcription factor |

| DFR | AT5G42800 | 1.60E-03 | 15 | 220 | 15 | 27 | 33 | 1 | Dihydroflavonol reductase |

| CHS1 | AT5G13930 | 3.96E-03 | 35 | 419 | 12 | 46 | 37 | 1 | Chalcone synthase |

| TT8 | AT4G09820 | 6.46E-03 | 7 | 69 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 1 | bHLH protein |

| TT5 | AT3G55120 | 5.06E-03 | 109 | 460 | 4 | 100 | 204 | 2 | Chalcone-flavanone isomerase |

| F3H | AT3G51240 | 9.45E-03 | 34 | 126 | 4 | 54 | 31 | 1 | Flavanone 3-hydroxylase |

| FLS | AT5G08640 | 3.82E-02 | 31 | 100 | 3 | 49 | 48 | 1 | Flavonol synthase |

| TT7 | AT5G07990 | 1.57E-03 | 14 | 44 | 3 | 13 | 11 | 1 | Flavonoid 3′-monooxygenase/flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H) |

| UGT78D1 | AT1G30530 | 1.12E-02 | 326 | 736 | 2 | 361 | 229 | 1 | UDP glucose:flavonoid 3-o-glucosyltransferase |

| Jasmonic | |||||||||

| ATTPSO3 | AT4G16740 | 1.54E-03 | 6 | 511 | 79 | 4 | 43 | 10 | Monoterpene synthase |

Absolute expression value of wild-type plants under normal conditions.

Absolute expression value of wild-type plants exposed for 2 h to drought stress.

Expression fold increase in wild-type dehydrated plants relative to control plants.

Absolute expression value of siz1-3 plants under normal conditions.

Absolute expression value of siz1-3 plants exposed for 2 h to drought stress.

Expression fold increase in siz1-3 dehydrated plants relative to control plants.

The results obtained in the microarray experiments were validated by quantitative RT-PCR analysis, which uncovered four gene categories (Figure 5). In the first category (Figure 5, panels 1 to 8), basal but not drought-inducible expression was reduced by SIZ1 deficiency. For example, under control conditions, SQS2 expression in the wild type was approximately threefold higher than in siz1-3 (Figure 5, panel 2, column WT C/siz1-3 C); however, the relative fold induction of this gene by drought was comparable in the mutant and the wild type (Figure 5, panel 2, columns WT D/C and siz1-3 D/C). These results show that under drought conditions, the expression of these groups of genes in siz1-3 was still threefold lower than that in the wild type. In the second category, exemplified by HMG1, basal level expression was reduced in siz1-3 compared with the wild type (Figure 5, panel 9, column WT C/siz1-3 C). On the other hand, drought treatment had little effect on HMG1 expression in the wild type but induced HMG1 expression by threefold in siz1-3 (Figure 5, panel 9, column siz1-3 D/C). The third category of genes included those encoding enzymes of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway (Figure 5, panels 10 to 13). Drought-inducible but not basal (Figure 5, columns siz1-3 D/C and WT C/siz1-3 C) expression of these genes clearly required SIZ1. Finally, expression of genes in the fourth category appear to be insensitive to SIZ1 abundance under both control and drought conditions (Figure 5; panels 14 to 16).

Figure 5.

SIZ1 Regulates Gene Expression.

Relative expression levels (fold difference) of 16 genes in wild-type and siz1-3 plants under control conditions (labeled as WT C/siz1 C), in wild-type plants after 2 h of drought stress with respect to wild-type plants under control conditions (labeled as WT D/C), and in siz1-3 plants after 2 h of drought stress with respect to siz1-3 plants under control conditions (labeled as siz1 D/C). The expression data were obtained by quantitative RT-PCR. Amplification of eIF4a mRNA within the same reactions was performed as a loading control. Error bars represent sd (n = 3). (1) DWF4, (2) SQS2, (3) DET2, (4) DWF1, (5) MYC2, (6) ANNAt4, (7) COR15a, (8) KIN1, (9) HMG1, (10) CHS1, (11) TT5, (12) DFR, (13) FLS, (14) RAB18, (15) DREB2A, and (16) COR47.

DISCUSSION

Compared with a growing long list of SUMO-modified proteins identified in yeast and mammals, little is known about sumoylated proteins and their roles in plants. In Arabidopsis, sumoylation has been implicated in stress responses (Kurepa et al., 2003; Miura et al., 2005, 2007; Yoo et al., 2006), ABA signaling (Lois et al., 2003), flowering-time regulation (Murtas et al., 2003), phosphorus starvation (Miura et al., 2005), and innate immunity (Lee et al., 2006). These results indicate a central role for the sumoylation process in environmental responses and in different aspects of plant development. Here, we describe the role of SIZ1, an Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligase (Miura et al., 2005), in Arabidopsis growth and drought stress tolerance.

SIZ1 Regulates Arabidopsis Growth

Because SIZ1 is expressed in almost all plant tissues (Figure 1), it is reasonable to assume that this E3 ligase plays a role in plant development. Morphological analysis showed that siz1-3 has reduced plant height and leaf size (Figure 2). Interestingly, although siz1 leaves show a decrease in cell size (2.3 times smaller than wild-type cells), this could not completely explain the reduction in leaf area (4.5 times smaller than the wild type) (Figure 2). These results suggest that SIZ1 is involved in cell expansion and cell proliferation. This phenotype can be attributed to a SIZ1 deficiency because wild-type morphology was restored in the complementation line, which displays comparable accumulation levels of SUMO proteins as wild-type plants (Figure 3).

Genome-wide expression analyses show that under normal growth conditions, SIZ1 regulates the expression of ∼1600 genes in Arabidopsis. Among these, 11 genes encode important components of the brassinosteroid biosynthetic and signaling pathway (Table 1, Figure 5). Similar to siz1-3, knockout mutants of some of these genes display a dwarf phenotype due to a defect in cell elongation (dwf1, Takahashi et al., 1995; det2, Li et al., 1996; dwf4, Azpiroz et al., 1998; hmg1, Suzuki et al., 2004) and cell proliferation (det2 and dwf1, Nakaya et al., 2002). Moreover, siz1-3 also shows a decrease in the expression of genes implicated in auxin signaling (Table 1), another hormone that regulates plant development (Tanaka et al., 2006). There is evidence for an interaction between brassinosteroid and auxin signaling and that brassinosteroid may act through an auxin-mediated pathway (Arteca et al., 1988; Mandava, 1988; Sasse, 1999; Nakamura et al., 2006). Taken together, these results suggest that SIZ1 modulates brassinosteroid biosynthesis and signaling pathways and, through these processes, Arabidopsis growth. One reasonable hypothesis is that a regulator of the brassinosteroid pathway is either activated or inactivated via sumoylation by SIZ1. That SIZ1 regulates plant growth is not surprising since in other eukaryotes a large number of proteins involved in different aspects of development are known to be sumoylated (Girdwood et al., 2004; Watts, 2004). Moreover, analysis of mutants affected in the SUMO protease, ESD4, uncovers a role of sumoylation in the regulation of flowering time and the control of plant development (Murtas et al., 2003). Recently, Miura et al. (2005) reported that SIZ1 is involved in the regulation of root growth in response to phosphate starvation.

Under normal growth conditions siz1-3 accumulated four times less anthocyanin than the wild type, indicating that SIZ1 positively regulates pigment accumulation in adult plants (5-week-old plants) (Figure 2C, panel d). Transcript analyses revealed that CHS1 levels were significantly lower in siz1-3, which may account for its lower anthocyanin content. This is consistent with previous notion that CHS1 plays a central role in flavonoid biosynthesis (Li et al., 1993; Saslowsky et al., 2000). The regulation by SIZ1 appears to be age dependent because CHS1 expression is only affected in adult plants (5-week-old plants). Deficiencies in anthocyanin accumulation have also been reported in dwf1, a brassinosteroid-deficient mutant (Luccioni et al., 2002). These data, together with our results, suggest that brassinosteroid regulates anthocyanin accumulation in adult plants and that SIZ1, and therefore the sumoylation process, mediates this process.

SIZ1 Is a Positive Regulator of Drought Tolerance

Previous work has reported an increase in the accumulation of SUMO-protein conjugates in response to abiotic stresses, such as heat shock, cold, ethanol, or H2O2 (Kurepa et al., 2003; Murtas et al., 2003; Yoo et al., 2006; Miura et al., 2007). Here, we show that Arabidopsis plants exposed to drought stress accumulate increased levels of sumoylated proteins by an ABA-independent pathway (Figure 3). Moreover, this increase is also highly dependent on SIZ1 activity since the accumulation of SUMO-protein conjugates is significantly lower in siz1-3 compared with the wild type. This SIZ1-mediated sumoylation likely plays an important role in conferring drought stress tolerance because siz1-3 plants were clearly more sensitive to drought stress compared with wild-type plants. In addition, this hypersensitive phenotype was completely rescued in plants of the complementation line (Figure 4). Consistent with its role in stress tolerance, SIZ1 levels transiently increase in response to drought (Figure 4). Our results, along with previous reports that siz1 mutants show a decrease in the accumulation of SUMO-protein conjugates under heat shock and cold (Miura et al., 2005, 2007; Yoo et al., 2006), suggest that SIZ1 plays a general role in abiotic stress responses.

We note that the accumulation of SUMO-protein conjugates in siz1-3, although significantly decreased compared with wild-type plants, remains inducible by drought stress, indicating the existence and contributions of additional and yet unidentified SUMO E3 ligases or other proteins with SUMO E3 ligase activity.

Genome-Wide Transcriptome Analysis of Arabidopsis Response to Drought Stress

Previous work has shown that the tolerance to drought stress is mediated by changes in gene expression (Seki et al., 2002; Shinozaki et al., 2003; Sakuma et al., 2006; Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 2006). Here, we present results of a genome-wide expression analysis of Arabidopsis plants subjected to drought. We found that after 2 h of exposure to dehydration, the expression level of 1700 Arabidopsis genes is induced more than two times (Table 2; see Supplemental Table 5 online). Seki et al. (2002) previously analyzed 7000 Arabidopsis genes and reported that 280 genes are induced more than five times under drought stress. We have expanded this analysis to the entire Arabidopsis genome (22,500 genes) and found ∼600 genes to be induced more than five times by this stress. Taken into consideration the differences in materials and experimental conditions between our experiments and those of Seki et al. (2002), we conclude that the results obtained are comparable. Several of these drought-inducible genes (e.g., DREB2A, MYC2, or ABF3) have previously been characterized as important regulators of this response (Shinozaki et al., 2003; Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 2006). Table 2 also includes genes that were previously reported as being involved in responses to other stresses but found to be drought inducible in our experiments. It is possible that these are general stress-responsive genes whose expression is induced by many stresses.

SIZ1 Regulates Both Basal and Drought-Inducible Gene Expression

Among the 1700 drought-inducible genes, the induction of 262 genes is positively regulated by SIZ1, demonstrating the important role of this SUMO E3 ligase in drought responses. Our analysis showed that SIZ1 could regulate either basal or drought-inducible gene expression (Figure 5). For example, basal but not drought-inducible expression of MYC2 and ANNAt4 is reduced by SIZ1 deficiency (Figure 5). Since optimal expression of these genes is needed for drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis (Abe et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2004), their lower expression in siz1-3 could account for the mutant's hypersensitivity to drought. By contrast, drought-inducible but not basal expression of four genes (CHS1, TT5, DFR, and FLS) implicated in the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway (Figure 5, panels 10 to 13) is regulated by SIZ1, consistent with the role of this SUMO E3 ligase in regulating anthocyanin accumulation in adult plants. Anthocyanin accumulation is an important component of the reactive oxygen species detoxification system in Arabidopsis (Nagata et al., 2003; Filkowski et al., 2004), and its reduced levels in siz1-3 may contribute to the mutant's hypersensitivity to drought stress and also suggest a role for anthocyanin in drought stress tolerance.

We found that basal expression of four genes involved in the brassinosteroid biosynthethic pathway (Figure 5, panels 1 to 4) is also reduced by SIZ1 deficiency, leading to an overall decrease in transcript levels of these genes even upon drought treatment. Kagale et al. (2006) have recently reported that treatment of Arabidopsis with brassinosteroids can increase its tolerance to drought stress. Therefore, it is likely that normal responses to drought may entail an increase in brassinosteroid accumulation. Future work should be directed toward the determination of a possible increase in brassinosteroid accumulation and increased flux through the brassinosteroid signaling pathway under drought and the possible role of brassinosteroid in conferring drought stress tolerance. Finally, drought induction of jasmonate-responsive genes has been previously reported (Fujita et al., 2006; Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 2006). Although these results suggest a role for jasmonate in drought stress response, the mechanism of action still remains unknown.

Results obtained with RD29B, PAP1, TT5, and ATTPSO3 indicated that SIZ1-independent pathways are also involved in the regulation of these genes in response to drought stress. Therefore, the function for SIZ1 in the response of Arabidopsis to drought stress is complex, and it may regulate different signaling pathways at different levels.

The tolerance of Arabidopsis to dehydration is mediated mainly by three independent signaling pathways: the first one is dependent on ABA, the second one is regulated by the transcription factor DREB2A, and the last one regulates ERD1 gene expression (Shinozaki et al., 2003; Sakuma et al., 2006; Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 2006). SIZ1 is not involved in the regulation of the two ABA-independent pathways because the expression of ERD1 and DREB2A, and some of its target genes (i.e., RD29A [data not shown] and COR47 [Figure 5]), is not affected in siz1-3. By contrast, SIZ1 is needed for the basal expression of some ABA-dependent genes (i.e., MYC2, COR15A, and KIN1; Figure 5) at wild-type levels, although ABA is not required for the accumulation of SUMO-protein conjugates and the drought induction of other ABA-dependent genes (i.e., CBF4 and RAB18; Figure 5) is not affected in siz1-3. Therefore, our results suggest that SIZ1 regulates part of the ABA-dependent signaling pathway by an ABA-independent process and SIZ1 likely acts in a new independent signaling pathway in the response to dehydration stress.

In conclusion, our results show that SIZ1 is an important component not only in the control of plant growth but also in drought stress responses. With respect to the former, SIZ1 appears to execute its function by regulating brassinosteroid and auxin pathways. With respect to the latter, the absence of SIZ1 activity reduces the expression of several key genes (e.g., MYC2 and ANNAT4) implicated in drought stress tolerance of Arabidopsis. Therefore, we can reasonably assume that the increased sensitivity of siz1 to drought can be attributed to the role of SIZ1 in drought stress responses. Considering that SIZ1 is a SUMO E3 ligase that most probably targets multiple substrates, protein sumoylation likely features prominently in drought tolerance. Our analysis of SUMO-protein conjugate levels in siz1-3 also indicates the existence of other proteins with SUMO E3 ligase activity in Arabidopsis (i.e., SUMO E2 conjugating enzymes and other SUMO E3 ligases). The identification of additional SUMO E3 ligases and the isolation and identification of sumoylated proteins will help to dissect the biological functions of the sumoylation machinery in plant growth and development.

METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Columbia) and siz1-3 mutant plants were used. Seeds of the T-DNA insertion line siz1-3 (SALK_034008) were obtained from the ABRC. Seeds were surface sterilized with 30% bleach containing 0.05% Triton X-100 for 15 min and rinsed five times with sterilized water. Unless specified, treated seeds were plated on MS medium with 1% sucrose (1× MS salt, pH 5.7, 1% sucrose, and 0.8% agar) and kept in darkness at 4°C for 4 d to break dormancy. Soil-grown plants were obtained by sowing seeds in pots containing a mixture of organic substrate and vermiculite (3:1 v/v). In all cases, plants were transferred to 16 h light/8 h dark at 22°C under white fluorescent light (70 μmol·m−2·s−1).

Three week-old plants were cut near the stem-root junction and the detached rosette place in a flow laminar hood for 2, 4, and 6 h. After treatments, plants were immediately frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C. Samples were used for RNA gel blot and protein gel blot experiments.

Water loss was investigated by two methods. Short-term assays were performed by allowing detached rosette of 4-week-old plants to dehydrate in a flow laminar hood, and the fresh weight was measured at different times after the treatment. Long-term experiments were performed by withholding water to 2-week-old plants grown on soil for 3 weeks, after which, the plants were watered again for 1 week. The number of plants that survived 1 week after resumption of watering was determined.

Plasmid Constructs

SIZ1 cDNA clone APZL63a07 (GenBank accession number AV530225) was obtained from the Kazusa DNA Research Institute. To facilitate subcloning of SIZ1 into different vectors, appropriate restriction sites were introduced by PCR with Pfu Turbo polymerase (Stratagene), and PCR products were verified by DNA sequencing. The binary vector pBA002 containing a 35S promoter was used for plasmid constructs (Kost et al., 1998).

Plant Protein Extraction and Protein Gel Blot Analysis of SUMO Conjugates

Approximately 200 mg of 3-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings were homogenized in 200 μL 4× SDS protein sampler buffer containing 5 mM N-ethylmaleimide (Murtas et al., 2003; Peng et al., 2003). Protein samples were resolved in 7.5% SDS/polyacrylamide gels, analyzed by protein gel blots with affinity-purified anti-SUMO1 or anti-SIZ1 polyclonal antibodies polyclonal antibodies, and detected with the ECL plus detection kit (Amersham Biosciences). Polyclonal antibodies were raised in rabbit by Cocalico and immunopurified using recombinant 6His-SUM1 or 6His-SIZ1.

GUS Staining

GUS staining was performed according to Hu et al. (2003).

RNA Isolation and Gel Blot Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from 3-week-old Arabidopsis plants using Qiagen RNeasy Plant Mini kits. For RNA gel blot analysis, 10 μg of total RNA was separated under denaturing conditions in a 1.5% agarose gel. SIZ1 mRNA was probed using a 493-bp fragment from the 15th exon of the SIZ1 gene amplified with the primer pair miz-9-F (5′-CGAGAATGATTTAGTGATC-3′) and miz-9-R (5′-TTTAAAACCCGACTGAGC-3′). The specific probes for KIN1 (Kurkela and Borg-Franck, 1992), CHS1, CHI, and PAL1 (Solfanelli et al., 2006) were obtained by PCR from genomic DNA of the Columbia-0 ecotype. Probe was prepared using a Rediprime II random primer labeling system (Amersham Biosciences), and hybridization was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA samples from each experiment were analyzed in at least two independent blots, and each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Complementation Experiments

Seeds harvested from heterozygous siz1-3 plants were germinated and grown on soil under short-day conditions (10 h light/14 h dark) for 5 weeks before being transferred to long-day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark) for 4 to 5 weeks. Flowering plants were transformed by vacuum infiltration via agrobacteria with 35S:HA-SIZ1 in a binary vector carrying Basta resistance. Basta-resistant plants were selected, and T-DNA insertion was determined by PCR screening to identify lines homozygous for insertion at the siz1 locus.

Analysis of Anthocyanin Content

Relative anthocyanin levels were determined according to Solfanelli et al. (2006).

Morphometric Measurements

The analysis of leaf length, width, and area was performed with the 5th leaf of 25-d-old (n = 12) wild-type and siz1-3 mutant plants using public domain image analysis software (ImageJ version 1.32; http://rbs.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Microarray Analysis

Genome-wide expression studies were performed with three biological replicates of wild-type and siz1-3 plants treated with drought stress for 0 or 2 h. One microgram of total RNA was used for reverse transcription using the MessageAmp II aRNA kit (Ambion) and 15 μg of labeled cRNA for hybridization. GeneChip (Affymetrix ATH1) hybridization and scanning were performed at the Genomic Resource Center (The Rockefeller University; http://www.rockefeller.edu/genomics). All microarray data will be available in the public repository Gene Expression Omnibus upon publication (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the accession number GSE6583.

Statistical Analysis of the Microarray Analysis

Statistical analysis of microarray data was performed using Genespring GX7.3.1 software (Agilent Technologies). After normalization using gcRMA, an analysis of variance test was used for the statistical analysis. The Welch t test (variances not assumed equal) was used for the parametric test, and the Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate for multiple testing corrections was used with a P value ≤ 0.05. By this statistical analysis, we generated lists of the genes that present significant differences in their expression between wild-type control and siz1-3 control, wild-type control and wild type exposed 2 h to drought stress, and wild type and siz1-3 both exposed 2 h to drought stress. All genes that were considered to show significant expression differences by the previous tests were then filtered by a twofold change of expression level between samples from wild-type and siz1-3 control plants, wild-type control and wild-type plants exposed 2 h to drought stress, and between wild-type and siz1-3 plants exposed 2 h to drought stress.

Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

Two micrograms of total RNA were used to reverse transcribe target sequences using oligo(dT) primer and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. PCR was performed in the presence of the double-stranded DNA-specific dye SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Amplification was monitored in real time with the 7900 HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). All reactions were performed in triplicate using three independent RNA samples. The sequences of the primers used are given in Supplemental Table 8 online.

Accession Number

The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative locus identifier and GenBank accession number for SIZ1 are At5g60410 and AV530225, respectively.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Phenotypes of siz1-3, the Wild Type, and C-siz1-3 after 25 d of Growth in in Vitro Conditions.

Supplemental Figure 2. Loss of Fresh Weight of Wild-Type, siz1-3, and C-siz1-3 Plants over Time.

Supplemental Table 1. Genes That Show Deregulated Expression in siz1-3 Relative to the Wild Type.

Supplemental Table 2. Genes Underexpressed in siz1-3 Plants (More Than Twofold Repression Relative to the Wild Type).

Supplemental Table 3. Genes Overexpressed in siz1-3 Plants (More Than Twofold Induction Relative to the Wild Type).

Supplemental Table 4. Genes Whose Expression Is Regulated by Drought in Wild-Type Plants.

Supplemental Table 5. Arabidopsis Drought-Inducible Genes (More Than Twofold Induction).

Supplemental Table 6. Drought-Inducible Genes That Show Deregulated Expression in Response to Drought in siz1-3 with Respect to the Wild Type.

Supplemental Table 7. Drought-Inducible Genes Downregulated in siz1-3 Relative to Wild-Type Plants.

Supplemental Table 8. Primers Used in the RT-PCR Experiment (Figure 5).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the ABRC for mutant seeds developed at the Salk Genomic Analysis Laboratory (http://signal.salk.edu), the Kazusa DNA Research Institute (http://www.kazusa.or.jp) for the SIZ1 cDNA clone, Shih-Shun Lin and Xunin Wang for help with the microarray experiment, and Qiwen Niu, Mengdai Xu, and Qinwen Zhou for technical assistance. We also thank Yu-Ren Yuan for purified SUM1. R.C. was supported by an EMBO fellowship (ALTF 562-2004). I.A.A. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship (SFRH/BPD/20581/2004/BH49) from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM44640 to N.-H.C.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Nam-Hai Chua (chua@rockefeller.edu).

Online version contains Web-only data.

References

- Abe, H., Urao, T., Ito, T., Seki, M., Shinozaki, K., and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. (2003). Arabidopsis AtMYC2 (bHLH) and AtMYB2 (MYB) function as transcriptional activators in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell 15 63–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arteca, R.N., Bachman, J.M., Tsai, D.S., and Mandava, N.B. (1988). Fusiccocin, an inhibitor of brassinosteroid-induced ethylene production. Physiol. Plant. 74 631–634. [Google Scholar]

- Azpiroz, R., Wu, Y., LoCascio, J.C., and Feldmann, K.A. (1998). An Arabidopsis brassinosteroid-dependent mutant is blocked in cell elongation. Plant Cell 10 219–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chosed, R., Mukherjee, S., Lois, L.M., and Orth, K. (2006). Evolution of a signalling system that incorporates both redundancy and diversity: Arabidopsis SUMOylation. Biochem. J. 398 521–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby, T., Matthai, A., Boeckelmann, A., and Stuible, H.P. (2006). SUMO-conjugating and SUMO-deconjugating enzymes from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 142 318–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar, G.A., Wilkinson, C.R., Jedrzejewski, P.T., and Finley, D. (2002). Role of a ubiquitin-like modification in polarized morphogenesis. Science 295 2442–2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filkowski, J., Kovalchuk, O., and Kovalchuk, I. (2004). Genome stability of vtc1, tt4, and tt5 Arabidopsis thaliana mutants impaired in protection against oxidative stress. Plant J. 38 60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, M., Fujita, Y., Noutoshi, Y., Takahashi, F., Narusaka, Y., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K., and Shinozaki, K. (2006). Crosstalk between abiotic and biotic stress responses: A current view from the points of convergence in the stress signaling networks. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9 436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill, G. (2003). Post-translational modification by the small ubiquitin-related modifier SUMO has big effects on transcription factor activity. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13 108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill, G. (2004). SUMO and ubiquitin in the nucleus: Different functions, similar mechanisms? Genes Dev. 18 2046–2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour, S.J., Artus, N.N., and Thomashow, M.F. (1992). cDNA sequence analysis and expression of two cold-regulated genes of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 18 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girdwood, D.W., Tatham, M.H., and Hay, R.T. (2004). SUMO and transcriptional regulation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 15 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay, R.T. (2001). Protein modification by SUMO. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26 332–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser, M. (2000). Evolution and function of ubiquitin-like protein-conjugation systems. Nat. Cell Biol. 2 E153–E157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser, M. (2001). SP-RING for SUMO: New functions bloom for a ubiquitin-like protein. Cell 107 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y., Xie, Q., and Chua, N.H. (2003). The Arabidopsis auxin-inducible gene ARGOS controls lateral organ size. Plant Cell 15 1951–1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E.S. (2004). Protein modification by SUMO. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73 355–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E.S., and Gupta, A.A. (2001). An E3-like factor that promotes SUMO conjugation to the yeast septins. Cell 106 735–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagale, S., Divi, U.K., Krochko, J.E., Keller, W.A., and Krishna, P. (2006). Brassinosteroid confers tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica napus to a range of abiotic stresses. Planta 225 353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerscher, O., Felberbaum, R., and Hochstrasser, M. (2006). Modification of proteins by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22 159–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kost, B., Spielhofer, P., and Chua, N.H. (1998). A GFP-mouse talin fusion protein labels plant actin filaments in vivo and visualizes the actin cytoskeleton in growing pollen tubes. Plant J. 16 393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurepa, J., Walker, J.M., Smalle, J., Gosink, M.M., Davis, S.J., Durham, T.L., Sung, D.Y., and Vierstra, R.D. (2003). The small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) protein modification system in Arabidopsis. Accumulation of SUMO1 and -2 conjugates is increased by stress. J. Biol. Chem. 278 6862–6872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurkela, S., and Borg-Franck, M. (1992). Structure and expression of kin2, one of two cold- and ABA-induced genes of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 19 689–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J., et al. (2006). Salicylic acid-mediated innate immunity in Arabidopsis is regulated by SIZ1 SUMO E3 ligase. Plant J. 49 79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S., Lee, E.J., Yang, E.J., Lee, J.E., Park, A.R., Song, W.H., and Park, O.K. (2004). Proteomic identification of annexins, calcium-dependent membrane binding proteins that mediate osmotic stress and abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16 1378–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Nagpal, P., Vitart, V., McMorris, T.C., and Chory, J. (1996). A role for brassinosteroids in light-dependent development of Arabidopsis. Science 272 398–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Ou-Lee, T.M., Raba, R., Amundson, R.G., and Last, R.L. (1993). Arabidopsis flavonoid mutants are hypersensitive to UV-B irradiation. Plant Cell 5 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois, L.M., Lima, C.D., and Chua, N.H. (2003). Small ubiquitin-like modifier modulates abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15 1347–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luccioni, L.G., Oliverio, K.A., Yanovsky, M.J., Boccalandro, H.E., and Casal, J.J. (2002). Brassinosteroid mutants uncover fine tuning of phytochrome signaling. Plant Physiol. 128 173–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandava, N.B. (1988). Plant growth-promoting brassinosteroids. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 39 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Melchior, F. (2000). SUMO–nonclassical ubiquitin. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16 591–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura, K., Jin, J.B., Lee, J., Yoo, C.Y., Stirm, V., Miura, T., Ashworth, E.N., Bressan, R.A., Yun, D.J., and Hasegawa, P.M. (2007). SIZ1-mediated sumoylation of ICE1 controls CBF3/DREB1A expression and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19 1403–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura, K., Rus, A., Sharkhuu, A., Yokoi, S., Karthikeyan, A.S., Raghothama, K.G., Baek, D., Koo, Y.D., Jin, J.B., Bressan, R.A., Yun, D.J., and Hasegawa, P.M. (2005). The Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1 controls phosphate deficiency responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102 7760–7765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtas, G., Reeves, P.H., Fu, Y.F., Bancroft, I., Dean, C., and Coupland, G. (2003). A nuclear protease required for flowering-time regulation in Arabidopsis reduces the abundance of SMALL UBIQUITIN-RELATED MODIFIER conjugates. Plant Cell 15 2308–2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, T., Todoriki, S., Masumizu, T., Suda, I., Furuta, S., Du, Z., and Kikuchi, S. (2003). Levels of active oxygen species are controlled by ascorbic acid and anthocyanin in Arabidopsis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51 2992–2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, A., Nakajima, N., Goda, H., Shimada, Y., Hayashi, K., Nozaki, H., Asami, T., Yoshida, S., and Fujioka, S. (2006). Arabidopsis Aux/IAA genes are involved in brassinosteroid-mediated growth responses in a manner dependent on organ type. Plant J. 45 193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya, M., Tsukaya, H., Murakami, N., and Kato, M. (2002). Brassinosteroids control the proliferation of leaf cells of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 43 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida, T., and Yasuda, H. (2002). PIAS1 and PIASxalpha function as SUMO-E3 ligases toward androgen receptor and repress androgen receptor-dependent transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 277 41311–41317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z., Shen, Y., Feng, S., Wang, X., Chitteti, B.N., Vierstra, R.D., and Deng, X.W. (2003). Evidence for a physical association of the COP9 signalosome, the proteasome, and specific SCF E3 ligases in vivo. Curr. Biol. 13 R504–R505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickart, C.M. (2001). Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70 503–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev, S., Bruhn, L., Sieber, H., Pichler, A., Melchior, F., and Grosschedl, R. (2001). PIASy, a nuclear matrix-associated SUMO E3 ligase, represses LEF1 activity by sequestration into nuclear bodies. Genes Dev. 15 3088–3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma, Y., Maruyama, K., Osakabe, Y., Qin, F., Seki, M., Shinozaki, K., and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. (2006). Functional analysis of an Arabidopsis transcription factor, DREB2A, involved in drought-responsive gene expression. Plant Cell 18 1292–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saslowsky, D.E., Dana, C.D., and Winkel-Shirley, B. (2000). An allelic series for the chalcone synthase locus in Arabidopsis. Gene 255 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasse, J. (1999). Physiological actions of brassinosteroids. In Brassinosteriods: Steroideal Plant Hormones, A. Sakurai, T. Yokota, and S.D. Clouse, eds (Tokyo: Springer-Verlag), pp. 137–161.

- Seki, M., et al. (2002). Monitoring the expression pattern of around 7,000 Arabidopsis genes under ABA treatments using a full-length cDNA microarray. Funct. Integr. Genomics 2 282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki, K., and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. (2006). Gene networks involved in drought stress response and tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 58 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki, K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K., and Seki, M. (2003). Regulatory network of gene expression in the drought and cold stress responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6 410–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solfanelli, C., Poggi, A., Loreti, E., Alpi, A., and Perata, P. (2006). Sucrose-specific induction of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 140 637–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, M., Kamide, Y., Nagata, N., Seki, H., Ohyama, K., Kato, H., Masuda, K., Sato, S., Kato, T., Tabata, S., Yoshida, S., and Muranaka, T. (2004). Loss of function of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase 1 (HMG1) in Arabidopsis leads to dwarfing, early senescence and male sterility, and reduced sterol levels. Plant J. 37 750–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, T., Gasch, A., Nishizawa, N., and Chua, N.H. (1995). The DIMINUTO gene of Arabidopsis is involved in regulating cell elongation. Genes Dev. 9 97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, Y., Kahyo, T., Toh, E.A., Yasuda, H., and Kikuchi, Y. (2001). Yeast Ull1/Siz1 is a novel SUMO1/Smt3 ligase for septin components and functions as an adaptor between conjugating enzyme and substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 276 48973–48977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, H., Dhonukshe, P., Brewer, P.B., and Friml, J. (2006). Spatiotemporal asymmetric auxin distribution: a means to coordinate plant development. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63 2738–2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungureanu, D., Vanhatupa, S., Kotaja, N., Yang, J., Aittomaki, S., Janne, O.A., Palvimo, J.J., and Silvennoinen, O. (2003). PIAS proteins promote SUMO-1 conjugation to STAT1. Blood 102 3311–3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierstra, R.D., and Callis, J. (1999). Polypeptide tags, ubiquitous modifiers for plant protein regulation. Plant Mol. Biol. 41 435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts, F.Z. (2004). SUMO modification of proteins other than transcription factors. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 15 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, C.Y., Miura, K., Jin, J.B., Lee, J., Park, H.C., Salt, D.E., Yun, D.J., Bressan, R.A., and Hasegawa, P.M. (2006). SIZ1 small ubiquitin-like modifier E3 ligase facilitates basal thermotolerance in Arabidopsis independent of salicylic acid. Plant Physiol. 142 1548–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiba, Y., Kiyosue, T., Katagiri, T., Ueda, H., Mizoguchi, T., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K., Wada, K., Harada, Y., and Shinozaki, K. (1995). Correlation between the induction of a gene for delta 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase and the accumulation of proline in Arabidopsis thaliana under osmotic stress. Plant J. 7 751–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.