Abstract

LR1 is a B cell-specific, sequence-specific DNA binding activity that regulates transcription in activated B cells. LR1 also binds Ig heavy chain switch region sequences and may function in class switch recombination. LR1 contains two polypeptides, of 106 kDa and 45 kDa, and here we report that the 106-kDa component of LR1 is nucleolin. This identification, initially made by microsequence analysis, was verified by showing that (i) LR1–DNA binding activity increased in B cells transfected with a nucleolin cDNA expression construct; (ii) LR1–DNA binding activity was recognized by antibodies raised against recombinant human nucleolin; and (iii) in B cells transfected with epitope-tagged nucleolin expression constructs, the LR1–DNA complex was recognized by the anti-tag antibody. Nucleolin is an abundant nucleolar protein which is believed to play a role in rDNA transcription or organization, or rRNA processing. Homology between nucleolin and histone H1 suggests that nucleolin may alter DNA organization in response to cell cycle controls, and the nucleolin component of LR1 may therefore function to organize switch regions before, during, or after switch recombination. The demonstration that nucleolin is a component of a B cell-specific complex that binds switch region sequences suggests that the G-rich switch regions may have evolved from rDNA.

Keywords: Ig, rDNA, recombination

LR1 is a B cell-specific, sequence-specific DNA binding activity. It was first identified as a factor that specifically recognizes Ig switch region sequences and is induced in primary B cells activated to carry out class switch recombination (1, 2). LR1 has also been shown to regulate transcription of two genes that function in B cell transformation, c-myc (3) and the Epstein–Barr virus EBNA-1 gene (4).

In Ig switch recombination, one constant region is literally switched for another by joining a rearranged and expressed variable region to a downstream constant region, deleting a long region of intervening DNA. Switching involves repetitive, G-rich regions of DNA, called switch regions (S regions), that are found upstream of the constant regions that undergo switch recombination (5–7). A specific S region is targeted for recombination by induction of noncoding transcripts from a promoter upstream of that S region (8–14), and recombination depends on both transcription and splicing of these switch transcript (15). Since S region transcription is prerequisite to recombination, it is possible that LR1 binding to sites in the S regions might potentiate S region transcription and thereby activate recombination. In vitro DNA binding studies have shown that the LR1–DNA binding consensus, GGNCNAG(G/C)CTG(G/A), is loose, and LR1 may bind multiple sites in each of the G-rich S regions. This suggests that another possible function for LR1 could be to organize S region DNA before, during, or after recombination.

To understand the function of LR1, we have purified and characterized the activity. LR1 is a complex of two polypeptides, of 106 kDa and 45 kDa (2, 16). In this communication we demonstrate that the 106-kDa polypeptide component of LR1 is nucleolin. Nucleolin is an abundant and highly modified protein found in nucleoli, the centers of ribosome biogenesis (17–22). Its N terminus is homologous to histone H1, and like many RNA-binding proteins, nucleolin contains both RNA recognition motifs (RRM) and Arg-Gly-Gly (RGG) motifs (see Fig. 1). The similarity between nucleolin and histone H1 has suggested that one role of nucleolin in the nucleolus may be to determine rDNA architecture (23, 24); and nucleolin may function analogously in switching, organizing S region DNA before, during, or after recombination in response to cell cycle controls. Nucleolin has also been thought to regulate rDNA expression; and the results we report provide the first conclusive evidence for participation of nucleolin in a transcription factor. Finally, the observation that nucleolin is a component of a factor that binds specifically to S regions suggests that S regions and rDNA are evolutionarily related. This possibility is in accord with early reports of sequence homology between rDNA and portions of the Ig heavy chain locus (25) and with functional studies showing that rDNA may have special properties in recombination (26–28).

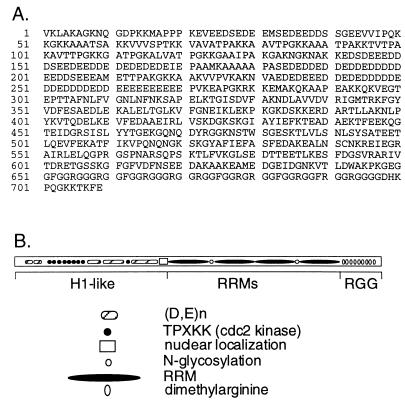

Figure 1.

Nucleolin. (A) Predicted amino acid sequence of human nucleolin. Residues 624–626 were omitted from the original published report (GenBank file humnucleo, accession number J05584J05584; ref. 22). (B) Schematic of nucleolin, showing the histone H1-like N-terminal region, which includes long runs of acidic amino acids and sites for cdc2 kinase; the nuclear localization signal and N-glycosylation sites; the four RRMs; and the RGG motifs in the C terminus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of LR1.

LR1 was purified from the human Epstein–Barr virus-transformed B cell line, Raji. Nuclear extract (29) from 40 L of cells was incubated with 20 ng/ml of biotinylated duplex DNA carrying the Sγ1 LR1 binding site (1) and, as nonspecific competitor, 2 μg/ml sonicated, boiled Escherichia coli DNA, in buffer L containing 0.2 M KCl; protein–DNA complexes were captured on streptavidin agarose (30); and protein was eluted with 0.6 M KCL in buffer L (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/2 mM EDTA/10% glycerol/1 mM DTT/1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride/10 μg/ml leupeptin/5 μg/ml benzamidine/5 μg/ml pepstatin A/5 μg/ml aprotinin). The eluate was dialyzed in buffer L containing 0.1 M KCl and chromatographed on DEAE-Sepharose using a gradient of 0.1–1.0 M KCl in buffer L. Fractions with LR1–DNA binding activity eluted between 0.45–0.6 M KCl and contained 106 kDa and 45 kDa polypeptides, as observed previously (2). The 106-kDa species was isolated by preparative SDS/PAGE and submitted in the gel slice to the W. M. Keck Foundation, Yale Medical School, where proteolysis with endoprotease lys C and peptide sequence analysis were carried out. Aware that nucleolin might copurify as a contaminant, we generated highly purified LR1 from the murine pre-B cell line, PD31. Attempts to remove nucleolin in the first purification step by DEAE chromatography resulted in loss of more than 90% of LR1–DNA binding activity, suggesting that, at least in nuclear extracts, nucleolin may contribute to the stability of the LR1–DNA binding activity. Instead, nuclear extract (31) from 40 L of cells was fractioned first on Heparin Hi-Trap; then by oligonucleotide capture, as described above; then on Mono Q (Pharmacia), using a 0.05–1.0 M NaCl gradient. Activity assays and immunoblotting showed that most (90%) of the LR1–DNA binding activity flowed through Mono Q, while most (>95%) of the nucleolin eluted at 0.4 M NaCl, as reported by others (32). The flow-through from the Mono Q column was then subjected to Mono S chromatography, using a 0.05–1.0 M NaCl gradient, and binding activity eluted at about 0.33 M NaCl. At this point the preparation was estimated to be at least 12,000-fold purified. The purified preparation, which specifically bound to duplex DNA carrying an LR1 site DNA (Kd ≈ 5 × 10−10 M), contained polypeptides of 106 kDa and 45 kDa. Immunoblotting showed the 106-kDa polypeptide to be nucleolin. The 45-kDa species was not recognized by antinucleolin antibodies and is a distinct polypeptide species (unpublished work).

Constructs and Transfections.

Nucleolin constructs were generated from a human nucleolin cDNA clone, generously provided by M. Srivastava (22), which we subcloned into the EcoRI site of pBS/KS+ (Stratagene) to create pBSNuc. For production of recombinant protein in E. coli, an NruI/MscI fragment was deleted from pBSNuc, leaving residues 284–709 of nucleolin, which was then cloned as an EcoRI fragment into the pMalc2 vector (New England Biolabs) to create pMalNuc. To express nucleolin under control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, the XbaI/EcoRV fragment from pBSNuc was ligated into SpeI/EcoRV-digested pCMV2R to generate pNFor4; pCMV2R is a derivative of pCMVβ (CLONTECH) into which the NotI/RsaI fragment of the pBS/KS+ polylinker has been inserted at the NotI site. A triple repeat of the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag YPYDVPDYAG (gift from D. Gonda, Yale Medical School) was inserted into nucleolin after amino acid 4 by amplification of DNA encoding the triple tag with PCR primers incorporating EcoRV sites, and ligation of the EcoRV-digested PCR product into the NruI site of pBSNuc. The tagged cDNA was cloned as an XbaI/EcoRV fragment into pCMV2R to create pNtag4. All PCR-generated regions in clones were sequenced throughout their length. PD31 murine pre-B cells were transfected with Qiagen (Chatsworth, CA) purified plasmid, as described (33). Nuclear extracts were made 40–48 hr later by extraction with 1 M KCl (31) and protein concentration measured by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Expression of the HA tag was confirmed by immunoblots of transfected cell extracts using the HA tag-specific mAb, 12CA5.

Antibodies, Immunofluorescent Staining, and Immunoblotting.

Antinucleolin antibodies were raised against a maltose binding protein fusion protein containing amino acids 284–709 of human nucleolin, which corresponds to the RRM and RGG domains (see Fig. 1). Extract was treated with 20 units/ml micrococcal nuclease and 10 μg/ml RNase A, then purified by successive steps of DEAE chromatography, amylose resin (New England Biolabs) affinity chromatography, and ion exchange chromatography on Mono S. New Zealand White rabbits were hyperimmunized with purified and denatured protein (100 μg/injection), and serum antibodies were purified by ammonium sulfate precipitation followed by affinity chromatography on Hi-Trap protein A Sepharose (Pharmacia), and concentrated on Centricon (Amicon). Immunofluorescent staining and immunoblotting were carried out as described by Li et al. (34) using anti-nucleolin antiserum at 1:50 dilution. The mAb 12CA5, specific for the HA epitope was prepared as high titer ascites fluid.

DNA Mobility-Shift Analysis.

Binding to a synthetic duplex oligonucleotide carrying the LR1 Sγ1 site was assayed by DNA mobility-shift, as described (1). Assays of crude nuclear extract contained 1 μg of protein per lane, and assays of purified LR1 contained ≈1 ng protein per lane. Gel shift assays used from 0–2 μg of purified rabbit serum antibodies or 1 μl 12CA5 ascites fluid. Quantification of band intensity was carried out using a Bio-Rad PhosphorImager.

RESULTS

Microsequence Analysis Shows the 106-kDa Component of LR1 to be Nucleolin, a 709-aa Polypeptide.

The 106-kDa band in the preparation of LR1 purified from Raji cells was digested with endoprotease lys C, and two sequenced peptides were found to be identical to predicted lysyl peptides of human nucleolin (22), peptide 1 to residues 523–536 and peptide 2 to residues 610–623. LR1–DNA binding activity is B cell specific. To ask if there might be a B cell-specific form of nucleolin, we isolated and sequenced 9 B cell nucleolin cDNAs. These clones all carried 9 nucleotide not present in the published sequence of nucleolin from a human retinal cDNA library (22). Resequencing the human retinal nucleolin cDNA clone (22) showed that a small region, encoding amino acid residues 624–626, had been omitted from the published sequence. The corrected sequence of the predicted human nucleolin polypeptide is shown in Fig. 1A, and the corresponding domains of the nucleolin polypeptide in Fig. 1B. We found no evidence for B cell-specific, alternatively spliced forms of nucleolin.

Nucleolin is an abundant protein, and it was possible that it might have copurified as a contaminant in the LR1 preparation. The oligonucleotide affinity chromatography step is of particular concern because others have observed nucleolin or nucleolin fragments in protein preparations purified by affinity chromatography using G-rich telomeric DNA sequences (35). Another preparation of LR1 was generated, from a murine pre-B cell line, purified 12,000-fold by four steps of column chromatography and demonstrated to contain nucleolin by immunoblotting (see Materials and Methods). Both the degree of purification and the relatively high salt used in chromatographic elution steps made it unlikely that nucleolin was a contaminant or was only weakly associated with the binding complex. We therefore set about to demonstrate as rigorously as possible that nucleolin is indeed a component of the LR1–DNA binding complex.

Recognition of LR1 by Polyclonal Antinucleolin Antibodies Generates a “Subshifted” Complex in Native Gels.

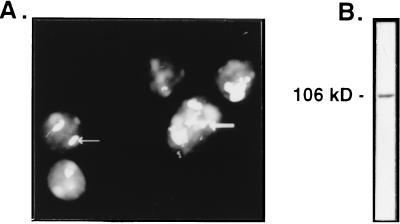

We raised rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the C terminus of recombinant human nucleolin (residues 284–709). As anti-DNA antibodies in the serum would interfere with gel mobility-shift assays of LR1 activity, the protein used for immunization was purified to homogeneity from nuclease-treated cell extract. The antibodies, purified by protein A affinity chromatography, specifically recognized nucleoli in immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 2A). They also specifically recognized the 106-kDa nucleolin polypeptide in PD31 cell nuclear extract, as shown by immunoblotting (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Specificity of antinucleolin antibodies. (A) In situ immunofluorescent staining of PD31 murine pre-B cells with antinucleolin antibodies. Arrows indicate two of the nucleoli evident by staining. (B) Immunoblot analysis of crude PD31 nuclear extract; the single band at 106 kDa is indicated.

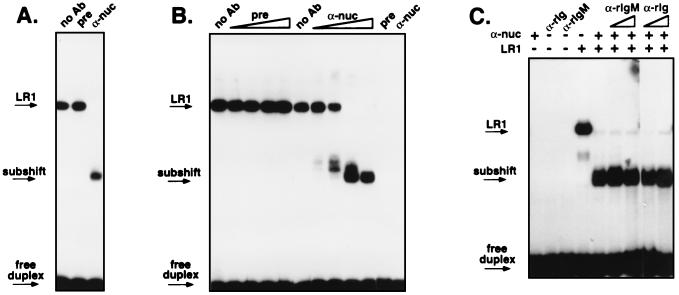

Recognition of LR1–DNA binding activity by the antinucleolin antibodies was tested by gel mobility-shift. Interaction of antibodies with a DNA binding protein typically has one of two effects on formation of a protein–DNA complex: the antibodies may inhibit binding, in which case no shifted band is evident; or the antibodies may further retard the mobility of the protein–DNA complex, producing a highly retarded band referred to as a supershift. As shown in Fig. 3, treatment of LR1 with the anti-nucleolin antibodies neither inhibited binding nor caused a supershift. Instead, the antibodies increased the mobility of the LR1–DNA complex, producing a “subshift.” Both crude extract (Fig. 3A) and highly purified LR1 (Fig. 3B) treated with the anti-nucleolin antibodies displayed an identical subshift, while antibodies from pre-immune serum had no effect on complex mobility.

Figure 3.

Gel mobility-shift analysis of the effect of antinucleolin antibodies on LR1–DNA binding activity. (A) Nuclear extract from PD31 pre-B cells was treated with no antibodies (no Ab) or 2 μg of protein A-purified antibodies from pre-immune serum (pre) or from a rabbit immunized with recombinant human nucleolin (α-nuc). Arrows indicate bands corresponding to the LR1–DNA complex (LR1), the subshift, and free DNA duplex. (B) LR1 purified 12,000-fold from PD31 pre-B cells was treated with 0, 0.016, 0.08, 0.4 or 2 μg of protein A purified antibodies from pre-immune serum (pre) or from a rabbit immunized with recombinant human nucleolin (α-nuc). Control lanes on the right show that neither antibody preparation alone altered mobility of the DNA duplex. (C) Purified LR1 was treated with 2 μg rabbit polyclonal antinucleolin antibodies in the presence of antirabbit Ig (α-rIg) or antirabbit IgM antibodies (α-rIgM) at 1 or 5 μg/reaction.

Several trivial explanations for the subshift can be ruled out. The subshift cannot be accounted for by anti-DNA activity of the antibodies, because migration of the labeled DNA duplex was not altered by incubation with the antibodies in the absence of LR1 activity (Fig. 3B Right). The subshift is unlikely to result from proteolysis, as the antibodies had been affinity purified on protein A, which should remove contaminating proteases; and antibodies from pre-immune serum had no effect on complex mobility either in crude extract (Fig. 3A) or highly purified protein preparations (Fig. 3B); and the antinucleolin antibodies had no effect on other protein-DNA interactions, including those of Sp1 and Ku (not shown). The subshift is not peculiar to a single antibody preparation, as serum from two different hyperimmunized rabbits produced a similar subshift.

One explanation for the subshift could be that interaction with antibodies alters the mobility of the binding complex to make it migrate faster. If so, there would be rabbit antibodies in the subshifted complex, and addition of anti-rabbit Ig to the binding complex should further alter complex mobility. We tested this possibility by treating purified LR1 with rabbit antinucleolin antibodies in the presence of anti-rabbit Ig. We tested both anti-rabbit IgM and anti-rabbit-Ig (all isotypes), in reactions that contained 1 or 5 μg of affinity-purified antirabbit Ig and 2 μg of serum antibodies from a rabbit immunized with recombinant nucleolin. As shown in Fig. 3C, even at 2.5-fold excess over rabbit serum antibodies, the anti-rabbit IgM or IgG antibodies had no effect on the mobility of the subshift.

The most likely explanation for the subshift therefore appears to be that the antinucleolin antibodies remove nucleolin from the DNA binding complex, leaving the remainder of the complex in contact with the DNA. Sadowski et al. (36) previously observed a subshift upon treatment of the small nuclear RNA promoter proximal sequence element bound to a complex called SNAPc with anti-TATA-box binding protein antibodies, which they interpreted as resulting from specific depletion of one component from the binding complex. Further experiments, described below, are consistent with this interpretation of the LR1 subshift.

Anti-Tag Antibodies Supershift Epitope-Tagged Nucleolin in the LR1–DNA Binding Complex.

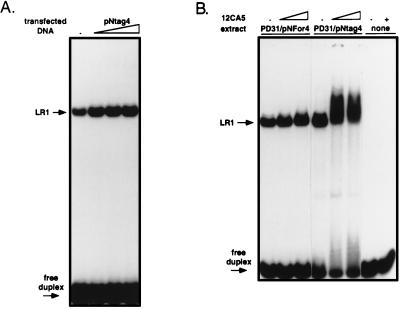

The sensitivity to antinucleolin antibodies illustrated in Fig. 3 shows that nucleolin, or a protein that shares epitopes with nucleolin, is present in the LR1–DNA binding complex. To determine whether the polypeptide recognized by the antibodies is bona fide nucleolin or a related protein, we transfected the murine pre-B cell line, PD31, with constructs in which the CMV promoter drives expression of either an unmodified nucleolin cDNA (pNFor4), or a nucleolin cDNA carrying an HA epitope tag at the amino terminus (pNtag4). Extracts were assayed for LR1–DNA binding activity by gel mobility-shift. Transfection with either pNtag4 (Fig. 4A) or pNFor4 (not shown) resulted in a 4-fold increase in LR1–DNA binding activity. Treatment with the anti-tag mAb, 12CA5, did not alter the mobility of shifted bands produced by nuclear extracts from cells transfected with the untagged construct, pNFor4 (Fig. 4B Left), but when nuclear extracts from cells transfected with pNtag4 were incubated with this antibody prior to the gel shift assay, the mobility of the protein–DNA complex was retarded (Fig. 4B Center). Only a fraction of the complexed DNA was supershifted, presumably because the tagged construct encodes only a fraction of the nucleolin in the LR1–DNA complex. Surprisingly, treatment of HA-tagged LR1 with the anti-tag monoclonal results in an increase in the amount of DNA bound by the protein. This is a reproducible effect of treating tagged LR1 with the 12CA5 mAb. One possible explanation is that interaction with the antibody increases affinity of LR1 for DNA. Control lanes (Fig. 4B Right) show that, in the absence of nuclear extract, the anti-tag antibody did not alter the mobility of the free labeled DNA duplex. We conclude that LR1–DNA binding activity contains bona fide nucleolin.

Figure 4.

Epitope-tagged nucleolin is found in the LR1–DNA binding complex. PD31 pre-B cells were mock-transfected (−) or transfected with the constructs indicated. (A) Gel mobility-shift analysis of nuclear extracts of PD31 pre-B cells transfected with increasing amounts (1, 2, 4, or 16 μg) of pNtag4, which expresses nucleolin cDNA carrying an N-terminal HA tag. (B) Gel mobility-shift analysis of nuclear extracts from cells transfected with 4 μg pNtag4, which expresses nucleolin cDNA carrying an N-terminal HA tag; or 4 μg pNfor4, which expresses untagged nucleolin cDNA. Reactions were treated with 0.3 or 1 μl of anti-tag mAb 12CA5, as indicated. Control lanes on the right show that the 12CA5 antibody preparation alone did not alter the mobility of the DNA duplex.

The HA epitope encoded by pNtag4 is at residue 4 of the N terminus of nucleolin. The observation that anti-tag antibodies recognize the LR1–DNA complex suggests that the N terminus of nucleolin is exposed in this complex. As shown in Fig. 1, this region contains long acidic stretches, including repeats of glutamate and aspartate up to 38 residues in length. Conceivably, these acidic regions within the N terminus might function as “acid blobs” and allow LR1 to activate transcription (3, 4) by ionic interactions with the basal transcription apparatus (37).

The Presence of Nucleolin in the LR1 Complex Diminishes Sequence Specificity of DNA Binding.

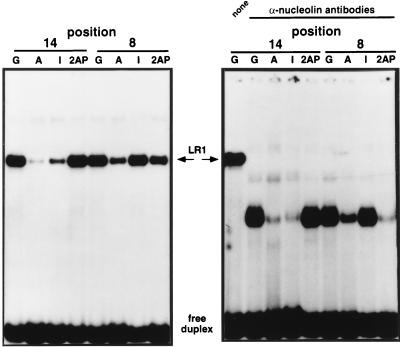

The experiments described above identify nucleolin as the 106-kDa component of LR1. As the 106-kDa polypeptide becomes covalently linked to DNA upon ultraviolet crosslinking (2, 16), nucleolin appears to make direct contact with DNA. To probe the role of nucleolin in LR1–DNA interaction, we assayed sequence-specificity of LR1 binding in the presence and absence of antinucleolin antibodies. Mutations at most positions in the LR1 site, CCTCCTGGTCAAGGCTGAA, do not affect LR1 binding, but mutation of either of the two underlined G residues to A diminishes binding 10-fold or more (ref. 1; and unpublished data). These two Gs are at positions 8 and 14 of the binding site. By replacing the underlined G residues with inosine or 2-aminopurine, we created a small panel of synthetic oligonucleotides that permitted us to analyze the specificity of LR1–DNA interactions. Inosine differs from G in lacking the N2 functional group in the minor groove, and 2-aminopurine differs from G in lacking the O6 group in the major groove. Binding of the LR1 complex to DNA is diminished by substitution of 2-aminopurine, but not inosine, at G8; and by substitution of inosine but not 2-aminopurine at G14 (Fig. 5 Left). When DNA binding was assayed in the presence of anti-nucleolin antibodies, binding to some of these oligonucleotides was altered (Fig. 5 Right). While binding to substitutions at position 14 was essentially unchanged, binding to G8I was somewhat reduced, and binding to G8–2AP was considerably reduced. Removal of nucleolin from the binding complex therefore renders binding more sensitive to certain substitutions. In the LR1 complex, nucleolin may relax stringency of DNA recognition and permit LR1 to bind S region DNA in a fashion that tolerates a greater degree of sequence heterogeneity.

Figure 5.

Gel mobility-shift analysis of LR1 binding to sites substituted with inosine (I) and 2-aminopurine (2-AP). Binding specificity of LR1 in PD31 nuclear extracts is compared in the absence (Left) and presence (Right) of antinucleolin antibodies.

DISCUSSION

LR1 is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein which regulates transcription in mammalian B cells and is likely also to function in switch recombination (1–4). LR1 contains two polypeptides, of 106 kDa and 45 kDa. The 106-kDa component of LR1 is nucleolin.

What is the role of nucleolin in LR1–DNA binding? The 106-kDa nucleolin polypeptide in the LR1 complex contacts DNA, as shown by ultraviolet crosslinking (1, 16). Nucleolin also affects sequence-specificity of DNA recognition, rendering binding less sensitive to certain substitutions. The Ig S regions are composed of repetitive, G-rich sequences which conform to a loose consensus. One function of nucleolin in LR1–DNA recognition may be to permit LR1 to bind a greater variety and number of sequences within the S regions.

Two results argue that nucleolin alone is not responsible for sequence-specific DNA binding by LR1. First, treatment of LR1 with antinucleolin antibodies depletes nucleolin from the complex without diminishing DNA binding. Second, while a recombinant fusion protein expressing the C-terminal RRM and RGG domains of nucleolin can bind to duplex DNA carrying an LR1 site, binding is reduced by three orders of magnitude and does not exhibit the sequence-specificity characteristic of the LR1 complex (unpublished data).

Others have identified nucleolin as a sequence-specific DNA binding protein (38, 39). In contrast to our experiments, these reports were based only upon microsequence analysis of purified protein and were not supported with evidence showing that antinucleolin antibodies recognized the DNA binding activity under investigation. As nucleolin is a very abundant protein, which could readily copurify as a contaminant, the significance of these reports is not clear. It has also been reported that recombinant nucleolin can interact with long subcloned fragments from the S regions (40). However, in these experiments DNA binding was assayed by Southwestern blotting and binding affinity was not reported.

The primary sequence and predicted structural motifs of nucleolin (Fig. 1) may provide clues relevant to the function of the LR1 complex in transcription and in recombination. The N terminus of nucleolin contains long acidic stretches, including three uninterrupted runs of 16, 21 and 38 amino acid residues, which could function as “acid blobs” (37) to regulate transcription. The N terminus is homologous to histone H1 and contains nine TPXKK motifs which are sites for phosphorylation by cdc2 kinase. Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of H1 at these sites is thought to facilitate chromosome condensation; and in the nucleolus, nucleolin is thought to enhance condensation of the actively transcribed rDNA at mitosis (23, 24). Nucleolin may organize the structure of the actively transcribed S regions in an analogous fashion, responding to cell cycle-specific controls before, during or after recombination. The central region of nucleolin is composed of four consensus RRMs (or RBDs), conserved domains of 90–100 amino acids that form β-sheet structures (reviewed in refs. 41 and 42). The RRMs are thought to provide a platform for protein-RNA contact, and the RNA exposed upon this platform is likely to be available for interaction. In LR1, the RRMs of nucleolin could function in interaction either with S region DNA or with the S region transcripts that are essential to recombination. The C terminus of nucleolin contains RGG motifs, also common in RNA binding proteins, which have been implicated in nucleolar localization (32, 43), RNA binding and RNA helix-destabilization (44). RGG motifs in other RRM-containing proteins have been shown to facilitate protein-mediated interactions of both RNA and DNA in vitro (45–48), a function of obvious utility in a polypeptide component of a complex that functions in recombination. In LR1, protein–protein interaction mediated by the C-terminal regions could juxtapose regions of DNA bound to protein. Taken together, these properties are consistent with a picture in which LR1 binds to multiple sites in each activated S region, and functions to organize S region DNA for transcription, recombination, or both.

LR1–DNA binding activity is B cell-specific, but nucleolin is ubiquitous. What accounts for the cell type-specificity of LR1 activity? Alternative processing of nucleolin mRNA could in principle provide a mechanism for cell type-specific modification of nucleolin, but we have not found evidence of alternative processing of the mRNA. Moreover, as tagged nucleolin expressed from a full-length cDNA clone appears in the LR1 shift, it is unlikely that alternative processing of nucleolin is key to producing this B cell-specific DNA binding activity. LR1–DNA binding activity is dependent on phosphorylation (2), which may regulate cell type-specificity. Nucleolin is known to be phosphorylated, N-glycosylated, and to contain dimethylated arginine residues in the C-terminal RGGs (17–22). We are now investigating the possibility there is distinct posttranslational modification of the nucleolin in the LR1 complex.

Switch recombination is characteristic of the mammalian immune response, and it has not been observed in lower vertebrates. This raises the question of how S regions and switch recombination evolved. Sequence homologies have been reported between rDNA and regions within the Ig loci (25), which may reflect a common origin or the G-rich base composition of both regions. There is also functional evidence that rDNA sequences can play special roles in recombination (26–28). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the HOT1 hotspot for mitotic recombination proved to be identical to the rDNA promoter (26). In Drosophila, active rDNA recombination can magnify rDNA repeats in somatic cells (27), and during meiosis the X and Y chromosomes pair in the vicinity of the nucleolus organizer—the rDNA. X chromosomes that lack the pairing region segregate randomly, but this can be corrected by P element insertion of an rDNA gene into heterochromatin, and in flies carrying such insertions, X chromosome pairing occurs at the site of rDNA insertion (28). Our demonstration that nucleolin is one part of a complex that interacts with S regions suggests that this protein may have followed its cognate DNA as it moved from one function to another. The G-rich rDNAs thus provide a plausible origin for the evolution of Ig S regions.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Gonda, W. McGinnis, W. Russ, J. Sedivy, and J. A. Steitz for insightful discussions; M. Srivastava for a human nucleolin cDNA clone; and J. Flory, K. Stone, and K. Williams of the W. M. Keck Foundation for oligonucleotide synthesis and protein sequence analysis. L.A.H. was the recipient of Predoctoral National Research Service Award 1F31GH00118, L.A.D was the recipient of Postdoctoral National Research Service Award 5F32GM15948, and this research was supported by Grant R01 GM39799 from the National Institutes of Health and Grant P01 CA16038 from the National Cancer Institute.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- S region

switch region

- RRM

RNA recognition motif

- HA

hemagglutinin

References

- 1.Williams M, Maizels N. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2353–2361. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12a.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams M, Hanakahi L A, Maizels N. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13731–13737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brys A, Maizels N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4915–4919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bulfone-Paus S, Dempsey L A, Maizels N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8293–8297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mowatt M R, Dunnick W A. J Immunol. 1986;136:2674–2683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nikaido T, Nakai S, Honjo T. Nature (London) 1981;292:845–848. doi: 10.1038/292845a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrini J, Shell B, Hummel M, Dunnick W. J Immunol. 1987;138:1940–1946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noelle R. Immunity. 1996;4:415–419. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coffman R L, Lebman D A, Rothman P. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:229–270. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60536-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cogne M, Lansford R, Bottaro A, Zhang J, Gorman J, Young F, Cheng H L, Alt F W. Cell. 1994;77:737–747. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu H, Zou R-R, Rajewsky K. Cell. 1993;73:1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90644-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung S, Rajewsky K, Radbruch A. Science. 1993;259:984–987. doi: 10.1126/science.8438159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Bottaro A, Li S, Steward V, Alt F W. EMBO J. 1993;12:3529–3537. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu L, Gorham B, Li S C, Bottaro A, Alt F W, Rothman P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3705–3709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorenz M, Jung S, Radbruch A. Science. 1995;267:1825–1828. doi: 10.1126/science.7892607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams M, Brys A, Weiner A M, Maizels N. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4935–4936. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.18.4935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sollner-Webb B, Mougey E B. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:58–62. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90025-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melese T, Xue Z. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:319–324. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bourbon H-M, Amalric F. Gene. 1990;88:187–196. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90031-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bourbon H-M, Lapeyre B, Amalric F. J Mol Biol. 1988;200:627–638. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90476-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lapeyre B, Bourbon H, Amalric F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1472–1476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.6.1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srivastava M, Fleming P J, Pollard H B, Bruns A L. FEBS Lett. 1989;250:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80692-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peter M, Nakagawa J, Doree M, Labbe J C, Nigg E A. Cell. 1990;60:791–801. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90093-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belenguer P, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Labbe J-C, Doree M, Amalric F. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:3607–3617. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnheim N, Seperack P, Banerji J, Lang R B, Miesfeld R, Marcu K B. Cell. 1980;22:179–85. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voelkel-Meiman K, Keil R L, Roeder G S. Cell. 1987;48:1071–1079. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawley R S, Tartof K D. Genetics. 1983;104:63–80. doi: 10.1093/genetics/104.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKee B D, Karpen G H. Cell. 1990;61:61–72. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90215-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dignam J D, Lebovitz R M, Roeder R. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hagenbüchle O, Wellauer P K. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3555–3559. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.14.3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schreiber E, Matthias P, Muller M M, Schaffner W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6419–6420. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heine M A, Rankin M L, DiMario P J. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:1189–1204. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.11.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li M-J, Leung H, Maizels N. In: Methods in Molecular Genetics. Adolph K W, editor. Orlando, FL: Academic; 1996. pp. 375–387. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li M-J, Peakman M-C, Golub E I, Reddy G, Ward D C, Radding C M, Maizels N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10222–10227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishikawa F, Matunis M J, Dreyfuss G, Cech T R. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4301–4310. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadowski, C. L., Henry, R. W., Lobo, S. M. & Hernandez, N. (1993) Genes Dev. 1535–1548. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Ptashne M. Nature (London) 1988;335:683–689. doi: 10.1038/335683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang T, Tsai W, Lee Y, Lei H, Lai M, Chen D, Yeh N, Lee S. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6068–6974. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dickenson L, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:456–465. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miranda G A, Chokler I, Aguilera R J. Exp Cell Res. 1995;217:294–308. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kenan D J, Query C C, Keene J D. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:214–220. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90088-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burd C G, Dreyfuss G. Science. 1994;265:615–621. doi: 10.1126/science.8036511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt-Zachmann M S, Nigg E A. J Cell Science. 1991;105:799–806. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.3.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghisolfi L, Joseph G, Amalric F, Erard M. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2955–2959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pontius B W, Berg P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8403–8407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Munroe S H, Dong X. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:895–899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.3.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Portman D S, Dreyfuss G. EMBO J. 1994;13:213–221. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu J, Maniatis T. Cell. 1993;75:1061–1070. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90316-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]