Abstract

Objective

While in western countries depression and heart disease often co-occur, less is known about the association of anxiety and alcohol use disorders with heart disease and about the cross-cultural consistency of these associations. Consistency across emotional disorders and cultures would suggest that relatively universal mechanisms underlie the association.

Method

Surveys in 18 random population samples of household-residing adults in 17 countries in Europe, the Americas, the Middle East, Africa, Asia and the South Pacific. Medically recognized heart disease was ascertained by self-report. Mental disorders were assessed with the WMH-CIDI, a fully structured diagnostic interview.

Results

Specific mood and anxiety disorders occurred among persons with heart disease at higher rates than among persons without heart disease. Adjusted for gender and age, the pooled odds ratios (95% CI) were 2.1 (1.9,2.5) for mood disorders, 2.2 (1.9,2.5) for anxiety disorders, and 1.4 (1.0,1.9) for alcohol abuse/dependence among persons with versus without heart disease. This pattern was similar across countries.

Conclusions

An excess of anxiety disorders, as well as mood disorders, is found among persons with heart disease. These associations hold across countries despite substantial between-country differences in culture and mental disorder prevalence rates. These results suggest that similar mechanisms underlie the associations and that a broad spectrum of mood-anxiety disorders should be considered in research on the comorbidity of mental disorders and heart disease.

Keywords: heart disease, depression, anxiety, substance abuse, cross-national

INTRODUCTION

Depression and ischemic heart disease are leading sources of disease burden world-wide [1-3]. Prior research has found that persons with heart disease are more likely to experience depressive illness and that comorbid depression is associated with a two fold or greater increased risk for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and new cardiovascular events [4-7] but convincing evidence that effective treatment of depression improves the prognosis of heart disease is lacking [8-10]. Multiple comorbidity mechanisms have been proposed to explain the association including health-related behaviors, impairments in autonomic function, elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines, increased platelet function e.g.[6,11-14].

To date, research on heart disease-mental disorder comorbidity has focused on depression and has largely been conducted in western countries [15-18]. Less is known about the association of heart disease with anxiety or alcohol use disorders, or about mental-physical comorbidity in developing countries and non-western cultures. Using data from the World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys in 17 countries in Europe, the Americas, Asia, the Middle East and Africa, we provide new information regarding the occurrence of common mental disorders among persons with heart disease and the consistency of the association across diverse western and non-western countries. This is important to know. If the association between heart disease and mental disorder is not limited to depression and western countries but consistently observed around the world and for other mental disorders than depression as well, it would support the position that relatively universal mechanisms underlie the association.

Studying mental-physical comorbidity for heart disease via morbidity survey in a wide range of developing countries necessitated reliance on self-report data. Mental disorders were assessed using a standardized diagnostic instrument. Regarding heart disease, respondents were asked if a medical doctor or other health professional had ever told them that they had heart disease. Although the WMH Surveys was unable to confirm this self-report of medically diagnosed heart disease by independent means, validity studies show that similar measures have acceptable validity when compared with medical records, with Kappa’s generally exceeding 0.60, sensitivities of 0.70 or more, and specificities of approximately 0.95 [19-22]. While it is certainly possible that recall bias due to mental illness affects research on perceived health and symptoms, it is far less so in research on medically diagnosed disorders e.g. [23,24]. While the limitations of self-report of medically recognized heart disease need to be borne in mind, this paper presents new information on the association of heart disease with mood, anxiety and alcohol use disorders in diverse countries world-wide. The objectives of this paper are: 1) to estimate the prevalence of specific mood, anxiety, and alcohol use disorders among persons with and without heart disease; and, 2) to assess whether these associations are consistent across culturally and socio-economically diverse countries.

METHODS

Samples

Eighteen surveys were carried out in 17 countries in the Americas (Colombia, Mexico, United States), Europe (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Ukraine), the Middle East/Africa (Israel, Lebanon, Nigeria, South Africa), Asia (Japan, separate surveys in Beijing and Shanghai in the People’s Republic of China), and the South Pacific (New Zealand). All surveys were based on multi-stage, clustered area probability household samples. All interviews were carried out face-to-face by trained lay interviewers. The six Western European surveys were carried out jointly.

Internal sub-sampling was used to reduce respondent burden by dividing the interview into two parts (except for Israel). Part 1 included the core diagnostic assessment of mental disorders. Part 2 included additional information relevant to a wide range of survey aims, including assessment of chronic physical conditions. All respondents completed part 1. All part-1 respondents who met criteria for any mental disorder and a probability sample of other respondents were administered part 2. The results from part-2 respondents were weighted by the inverse of their probability of selection for part-2 of the interview to adjust for differential sampling. Analyses in this article were based on the weighted part-2 sample. Additional weights were used to adjust for differential probabilities of selection within households and to match the samples to population socio-demographic distributions. The samples showed substantial cross-national differences in age structure (younger in less-developed countries) and educational status (lower in less-developed countries) but not in gender distribution.

Training and Field Procedures

The central World Mental Health (WMH) staff trained bilingual supervisors in each country. Consistent interviewer training documents and procedures were used across surveys. The WHO translation protocol was used to translate instruments and training materials. Standardized descriptions of the goals and procedures of the study, data usage and protection and the rights of respondents were provided in both written and verbal form to all potentially eligible respondents before obtaining verbal informed consent for participation in the survey. Quality control protocols, described in more detail elsewhere [25], were standardized across countries to check on interviewer accuracy and to specify data cleaning and coding procedures. The institutional review board of the organization that coordinated the survey in each country approved and monitored compliance with procedures for obtaining informed consent and protecting human subjects.

Mental disorder status

All surveys used the World Mental Health Survey version 3.0 of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview [26], a fully structured diagnostic interview, to assess disorders and treatment. Disorders considered in this paper include the anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and/or agoraphobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and social phobia), mood disorders (dysthymia and major depressive disorder), and alcohol use disorders (alcohol abuse and dependence). Disorders were assessed using the definitions and criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) [27]. CIDI organic exclusion rules were imposed in making all diagnoses. The WHO-CIDI Field Trials and later clinical calibration studies showed that the 12-month prevalence of the disorders considered herein were assessed with acceptable reliability [25].

Heart disease status

In a series of questions about chronic conditions adapted from the U.S Health Interview Survey [19], respondents were asked about the presence of selected chronic conditions. More specifically, respondents were asked if a medical doctor or other health professional had ever told them that they had heart disease. Self-reports of medically diagnosed heart disease have been shown to have acceptable validity, with some underreporting but little overreporting [19-22]. Self-report measures of heart disease have been used previously in research on heart disease and psychopathology [28-31], but the limitations and potential biases of self-report of medically recognized heart disease need to be considered in interpreting the results of the World Mental Health Surveys.

Analysis Methods

This paper reports prevalence rates for specific mental disorders among persons with and without heart disease. For each survey, all odds ratios quantifying the association of each mental disorder with heart disease were estimated while adjusting for age and sex. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals for the prevalence rates and for the odds ratios were estimated using the Taylor Series method [32] with SUDAAN software [33] to adjust for clustering and weighting. Pooled estimates of mental disorder prevalence rates were not reported due to the large variation in mental disorder prevalence rates across surveys.

Using meta-analytic methods, pooled estimates of the odds ratios from the 18 surveys were calculated describing the overall association of each mental disorder with heart disease. The pooled estimate of the odds ratio was weighted by the inverse of the variance of the estimate for each survey. We report the confidence intervals of the pooled odds ratio estimates [34]. For each association of a specific mental disorder with heart disease, we assessed whether the heterogeneity of the odds ratio estimates across surveys was greater than expected by chance [34]. Since these tests were non-significant except for agoraphobia/panic, we report pooled estimates of the odds ratios, and confidence intervals for the pooled estimates.

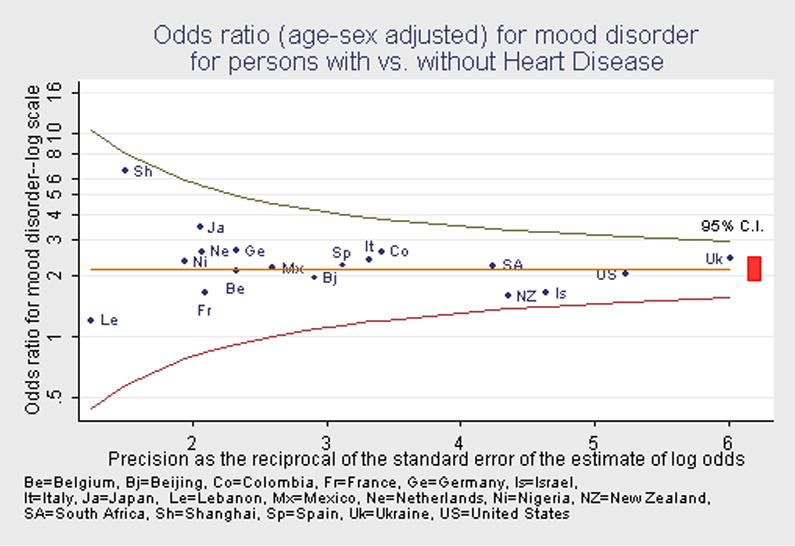

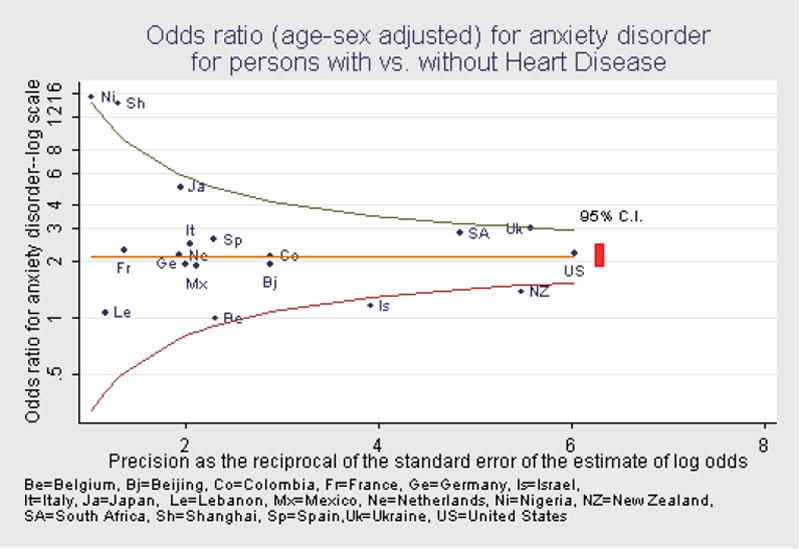

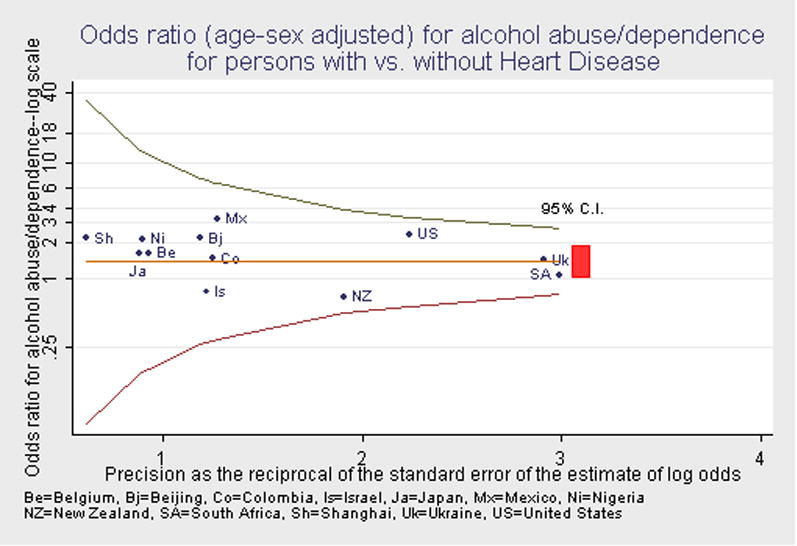

The adjusted odds ratios, and the pooled estimate and its confidence intervals, are displayed for each survey using a funnel graph [35]. The “funnel” in these graphs shows the 95 percent confidence interval band for a survey estimate that would include the pooled estimate of the odds ratio at varying levels of precision. Precision is defined as the reciprocal of the standard error of the odds ratio estimate. On these graphs the less precise estimates are to the left (where the funnel is wider), and the more precise estimates are to the right (where the funnel is narrower). These graphs provide a visual summary of the association of any mood disorder and of any anxiety disorder with heart disease across the participating surveys.

The prevalence of heart disease is so low in younger people that the statistical adjustment for age may not be entirely without risk as it might obscure differences in the strength of the associations of interest between younger and older respondents. Therefore we reran the analyses described above for respondents of 50 years and older.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Survey sample sizes ranged from 2372 (Netherlands) to 12,992 (New Zealand), with a total of 85,052 participating adults in Part 1 and 43,249 in Part II. Response rates ranged from 45.9% (France) to 87.7% (Colombia), with a sample size weighted average of 70.5 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics, and Heart Disease Prevalence

| Country | Sample (N) | Mean ageΦ | % 60 years or older | % women | Education secondary or greater | Heart Disease PrevalenceΦΦ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevelace (N) | Weighted % | ||||||

| Americas | |||||||

| Colombia | 2381 | 36.6 | 5.3 | 54.5 | 46.4 | 108 | 3.0 |

| Mexico

United States |

2362

5692 |

35.2

45.0 |

5.2

21.2 |

52.3

53.0 |

31.4

83.2 |

78

399 |

2.3

7.0 |

| Asia & S. Pacific | |||||||

| Japan | 887 | 51.4 | 34.9 | 53.7 | 70.0 | 70 | 6.1 |

| PRC-Beijing | 914 | 39.8 | 15.6 | 47.5 | 61.4 | 129 | 10.1 |

| PRC -Shanghai | 714 | 42.9 | 18.7 | 48.1 | 46.8 | 100 | 12.4 |

| New Zealand | 7312 | 44.6 | 20.7 | 52.2 | 60.4 | 504 | 6.7 |

| Europe | |||||||

| Belgium | 1043 | 46.9 | 27.3 | 51.7 | 69.7 | 105 | 8.9 |

| France | 1436 | 46.3 | 26.5 | 52.2 | NA | 74 | 5.6 |

| Germany | 1323 | 48.2 | 30.6 | 51.7 | 96.4 | 121 | 8.8 |

| Italy

Netherlands |

1779

1094 |

47.7

45.0 |

29.2

22.7 |

52.0

50.9 |

39.5

69.7 |

104

104 |

5.4

7.8 |

| Spain | 2121 | 45.5 | 25.5 | 51.4 | 41.7 | 122 | 4.5 |

| Ukraine | 1720 | 46.1 | 27.3 | 55.1 | 79.5 | 582 | 25.0 |

| Middle East and Africa | |||||||

| Lebanon | 602 | 40.3 | 15.3 | 48.1 | 40.5 | 31 | 3.3 |

| Nigeria | 2143 | 35.8 | 9.7 | 51.0 | 35.6 | 36 | 1.7 |

| Israel | 4859 | 44.4 | 20.3 | 51.9 | 78.3 | 511 | 9.4 |

| South Africa | 4315 | 37.1 | 8.8 | 53.6 | 38.9 | 297 | 6.1 |

Age range > 18, except for Colombia, Mexico (18-65), Japan (> 20) and Israel (>21)

Lifetime Prevalence reported

Self-reported heart disease was common in all of the participating countries. Excluding the Ukraine where the prevalence of self-reported heart disease was exceptionally high (25%), the prevalence ranged from 1.7% in Nigeria to 12.4% in Shanghai, suggesting substantial across country variation (Table 1). European, Asian, and North-American countries had a higher prevalence of heart disease than South American, Arabic Middle-East and African countries. Prevalence was higher among older persons, among those with less than 12 years of education, and generally among men (data available on request). Exceptions to this pattern included the Ukraine (31.0% prevalence for females vs. 17.5 for males) and Beijing (12.7% prevalence for females vs. 7.7% for males).

Mood disorders and heart disease

Major depression was typically common among persons with heart disease (see Table 2) and generally fell in the 3-9% range. The prevalence rates of dysthymia were typically much lower, generally falling in the vicinity of 1-3%. Comparison of the prevalence rates of major depression and dysthymia among persons with versus without heart disease showed small absolute differences in many countries, with a few countries showing slightly lower prevalence rates (<1%) among persons with heart disease (e.g. Lebanon), but these unadjusted comparisons do not take age and sex differences of persons with vs. without heart disease into account.

Table 2.

12-month prevalence (%) of mood disorders among persons with vs. without heart disease

| Major Depression | Dysthymia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | No Heart Dis | Heart Dis | OR (CI) | No Heart Dis | Heart Dis | OR (CI) |

| Colombia | 5.9 | 13.9 | 2.6 (1.5, 4.8) * | 0.9 | 5.0 | 5.6 (1.8, 17.4) * |

| Mexico | 4.0 | 8.7 | 2.1 (1.0, 4.5) | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 (0.2, 3.9) |

| United States | 8.2 | 9.2 | 2.1 (1.4, 3.2) * | 2.2 | 3.7 | 2.6 (1.5, 4.8) * |

| Japan | 2.1 | 4.6 | 3.2 (1.1, 8.9) * | 0.6 | 2.7 | 4.6 (1.0, 20.7) * |

| Beijing | 2.3 | 3.1 | 2.0 (1.0, 4.0) | 0.3 | 0.9 | 2.0 (0.4, 9.4) |

| Shanghai | 0.9 | 6.9 | 7.4 (1.9, 29.4) * | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 (0.0, 4.8) |

| New Zealand | 6.8 | 4.2 | 1.4 (0.9, 2.3) | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.8 (1.0, 3.3) |

| Belgium

France |

5.6

6.1 |

5.6

6.4 |

1.9 (0.7, 5.6)

2.1 (0.7, 5.8) |

1.1

1.6 |

3.0

1.4 |

2.3 (0.7, 7.4)

0.9 (0.2, 3.5) |

| Germany

Italy |

3.0

3.0 |

3.3

5.7 |

2.0 (0.7, 6.1)

2.0 (1.0, 4.3) |

0.7

0.8 |

3.1

4.8 |

4.2 (1.1, 15.9) *

4.3 (2.2, 8.3) * |

| Netherlands

Spain |

5.1

3.9 |

7.4

7.4 |

2.8 (1.0, 7.8) *

2.3 (1.1, 4.8) * |

1.7

1.3 |

2.9

4.1 |

3.8 (0.4, 37.8)

3.3 (1.3, 8.5) * |

| Ukraine

Lebanon |

6.4

1.8 |

18.6

1.3 |

2.5 (1.8, 3.5) *

1.2 (0.2, 6.2) |

2.5

0.7 |

9.0

0.0 |

2.3 (1.6, 3.3) *

NE |

| Nigeria

Israel |

1.1

5.9 |

2.4

8.0 |

2.3 (0.8, 6.5)

1.6 (1.0, 2.4) * |

0.2

1.1 |

0.4

2.1 |

1.9 (0.2, 21.6)

1.7 (0.8, 3.5) |

| South Africa | 4.5 | 10.3 | 2.2 (1.4, 3.6) * | 0.1 | 0.0 | NE |

| Pooled Odds Ratio | - | - | 2.1 (1.8, 2.4) * | - | - | 2.4 (2.0, 3.0) * |

NE means non-estimable

As shown in Table 2, age and sex adjusted odds ratios measuring the association of major depression with heart disease were significantly greater than one (indicating a positive association greater than expected by chance) for 9 of 18 surveys for which odds ratios were calculated. The remaining odds ratios were all larger than 1.0. The odds ratios also indicated a significant association between heart disease and dysthymia for 7 of the 16 surveys for which odds ratios were estimated. We assessed whether the variability in the odds ratio estimates across the surveys was greater than expected by chance [34]. The resulting test of heterogeneity was non-significant for both major depression (p=0.83) and for dysthymia (p=0.38), so it is appropriate to report a pooled estimate. The pooled estimate of the odds ratio for major depression was 2.1, while the pooled estimate of the odds ratio for dysthymia was 2.4. In the subgroup of older respondents (50+) these odds ratios were 1.9 and 2.3.

Figure 1 shows a funnel graph of the age-sex adjusted odds ratios for mood disorders (major depression and/or dysthymia present) for all 18 surveys. In this graph, the odds ratio is plotted on a log scale as a function of the precision of the estimate of the odds ratio. The funnel lines show whether the 95% confidence interval of each survey’s estimate of the odds ratio includes the pooled estimate, given the precision of the survey’s estimate. Most of the odds ratio estimates clustered in proximity to the pooled estimate of 2.1. The 95% confidence intervals of all of the survey estimates included the pooled estimate, with the more discrepant estimates tending to be those with lower precision.

Figure 1.

Odds ratio (age-sex adjusted) for mood disorder for persons with vs. without Heart Disease

Anxiety disorders and heart disease

Across the surveys, the specific anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, panic/agoraphobia, social phobia and post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD) were generally less prevalent than major depression. Among persons with heart disease, the prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) ranged from circa 0.3% in Lebanon to about 5% in the Ukraine, the U.S and France (Table 3). The prevalence of agoraphobic/panic among persons with heart disease typically fell in the 1-5% range (Table 3). Social phobia was rarely found among persons with heart disease in Beijing, Shanghai, Belgium, Germany, Lebanon, and Nigeria. The prevalence of social phobia ranged from 1% (Spain) to 6% (U.S.) among persons with heart disease in the remaining surveys (Table 3). PTSD was relatively uncommon among persons with heart disease in many of the participating surveys but had a prevalence of 2% or more in the US, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Ukraine (Table 3).

Table 3.

3A: 12-month prevalence (%) of anxiety disorders among persons with vs. without heart disease

| Generalized Anxiety | Agoraphobia or Panic Disorder | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | No Heart Dis | Heart Dis | OR (CI) | No Heart Dis | Heart Dis | OR (CI) |

| Colombia | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.6 (0.4, 6.3) | 2.1 | 4.9 | 2.5 (1.0, 6.3) |

| Mexico | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.7 (0.2, 11.6) | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.4 (0.1, 1.9) |

| United States | 4.0 | 4.9 | 1.9 (1.2, 3.0) * | 3.6 | 4.0 | 2.0 (1.3, 3.0) * |

| Japan | 1.4 | 4.2 | 3.1 (0.9, 10.9) | 0.5 | 2.8 | 15.9 (4.4, 58.0) * |

| Beijing | 1.0 | 2.4 | 2.0 (0.9, 4.5) | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 (0.0, 12.0) |

| Shanghai | 0.2 | 4.6 | 12.3 (2.4, 62.4) * | 0.0 | 1.0 | NE |

| New Zealand | 3.1 | 2.6 | 1.6 (0.9, 2.6) | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.4 (1.2, 4.6) * |

| Belgium | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.7 (0.2, 2.7) | 1.6 | 0.0 | - (-,-) |

| France | 1.9 | 5.3 | 5.7 (0.8, 40.7) | 1.2 | 3.8 | 6.4 (1.7, 24.7) * |

| Germany | 0.4 | 1.3 | 10.5 (1.5, 74.0) * | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.5 (0.3, 7.5) |

| Italy | 0.5 | 0.8 | 2.0 (0.3, 16.5) | 1.0 | 1.8 | 2.2 (0.4, 11.0) |

| Netherlands | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 (0.0, 6.0) | 1.6 | 2.5 | 3.0 (0.9, 10.0) |

| Spain | 0.9 | 1.8 | 2.1 (0.6, 7.5) | 0.8 | 1.7 | 2.6 (0.7, 8.9) |

| Ukraine | 1.3 | 5.4 | 3.3 (2.1, 5.4) * | 0.9 | 4.7 | 4.9 (2.9, 8.2) * |

| Lebanon | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.7 (0.2, 15.3) | 0.2 | 0.0 | NE |

| Nigeria | 0.0 | 0.0 | NE | 0.2 | 6.0 | 32.6 (4.5, 234.4) * |

| Israel | 2.6 | 2.8 | 1.1 (0.6, 2.1) | 0.9 | 1.5 | 1.5 (0.7, 3.4) |

| South Africa | 1.7 | 5.1 | 2.3 (1.1, 4.9) * | 5.1 | 13.0 | 2.7 (1.7, 4.1) * |

| Pooled Odds Ratio | - | - | 2.1 (1.7, 2.5) * | - | - | 2.7 (2.2, 3.3) * |

| 3B: 12-month prevalence (%) of anxiety disorders among persons with vs. without heart disease (continued) | ||||||

| Social Phobia | PTSD | |||||

| Country | No Heart Dis | Heart Dis | OR (CI) | No Heart Dis | Heart Dis | OR (CI) |

| Colombia | 2.8 | 4.8 | 2.1 (0.8, 5.1) | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.9 (0.1, 5.7) |

| Mexico | 1.9 | 5.0 | 2.9 (1.1, 7.7) * | 0.6 | 1.1 | 2.5 (0.6, 10.7) |

| United States | 6.9 | 6.0 | 1.6 (1.0, 2.6) | 3.5 | 4.8 | 2.7 (1.7, 4.3) * |

| Japan | 0.5 | 2.0 | 9.3 (1.7, 51.2) * | 0.4 | 0.0 | NE |

| Beijing | 0.3 | 0.7 | 5.3 (1.2, 24.1) * | 0.2 | 0.8 | 3.3 (0.5, 23.3) |

| Shanghai | 0.0 | 0.0 | NE | 0.1 | 0.4 | 6.8 (0.4, 124.2) |

| New Zealand | 5.2 | 2.4 | 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.5 (0.9, 2.5) |

| Belgium

France |

1.2

2.7 |

0.4

1.6 |

1.6 (0.1, 18.9)

1.0 (0.1, 7.7) |

0.7

2.3 |

0.8

2.4 |

2.7 (0.8, 9.0)

2.2 (0.4, 11.7) |

| Germany

Italy |

1.9

1.0 |

0.6

2.8 |

0.8 (0.2, 3.6)

4.2 (0.9, 19.1) |

0.7

0.7 |

0.7

1.6 |

3.2 (0.7, 15.2)

1.9 (0.4, 8.9) |

| Netherlands

Spain |

1.2

0.7 |

2.4

0.9 |

4.2 (1.2, 14.7) *

4.0 (0.3, 52.8) |

2.3

0.5 |

4.8

0.7 |

2.5 (0.4, 14.1)

1.5 (0.3, 6.3) |

| Ukraine

Lebanon |

2.0

0.6 |

2.2

0.0 |

1.8 (0.9, 4.0)

NE |

1.6

1.7 |

6.3

0.9 |

3.3 (1.9, 5.6) *

1.1 (0.1, 10.6) |

| Nigeria

Israel |

0.3

- |

0.0

- |

NE

NE |

0.0

0.5 |

0.0

0.8 |

NE

1.5 (0.3, 7.0) |

| South Africa | 1.7 | 5.0 | 3.4 (1.6, 7.0) * | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.5 (0.3, 7.4) |

| Pooled Odds Ratio | - | - | 1.9 (1.5, 2.5) * | - | - | 2.3 (1.8, 2.9) * |

NE means non-estimable

Because the specific anxiety disorders were less common, odds ratios were not estimated for all of the participating surveys due to a null cell. Given the relatively small sample sizes, it is not surprising that the odds ratio estimates were often not significantly different from 1.0, even when the odds ratio estimates were consistent with the pooled estimate. The odds ratios for anxiety disorders tended to be greater than one, although the point estimates showed greater variability than for mood disorders, possibly due to the lower sample size of cases. The heterogeneity tests for the odds ratios were non-significant for generalized anxiety disorder (p=0.12), social phobia (p=0.08) and for PTSD (p=0.90) but were significant for agoraphobia/panic (p=0.003), indicating that the pooled estimate for this disorder masks significant heterogeneity across surveys. Across the four anxiety disorders, the pooled odds ratio estimates were all significantly greater than one, falling in the 1.9 to 2.7 range. In the subgroup of older respondents (50+) the odds ratios were also statistically significant and ranged from 1.5 to 2.6.

The association of any anxiety disorder with heart disease (Figure 2) showed a pattern similar to that observed for any mood disorder (Figure 1). The pooled estimate of the odds ratio was 2.2, with a 95% confidence interval of 1.9 to 2.5. Of the 18 survey-specific estimates, 14 had 95% confidence intervals that included the pooled estimate. Of the four estimates whose 95% confidence interval did not include the pooled estimate, two had low precision (Nigeria and Shanghai), but two had high precision (Israel and New Zealand). Overall, these results indicate that the strength of the association of anxiety disorders, as a class, with heart disease is comparable to that observed for mood disorders—an odds of about 2 to 1 of anxiety disorder for persons with versus without heart disease.

Figure 2.

Odds ratio (age-sex adjusted) for anxiety disorder for persons with vs. without Heart Disease

Alcohol use disorders and heart disease

In 11 of the 18 surveys, as shown in Table 4, one percent or less of those with heart disease met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence. In the remaining surveys, the prevalence of alcohol abuse or dependence ranged from 1.4% (Japan) to about 4.5% (Mexico, Ukraine). Odds ratios for the association of alcohol abuse or dependence with heart disease were estimated for 12 surveys. These odds ratios were nearly all larger than 1.0 (except New Zealand and Israel) but not significantly. Since the prevalence of alcohol use disorders decreases markedly with age, while the prevalence of heart disease increases with age, adjustment for age (and sex) is important in assessing their association. The odds ratios estimates were not found to be heterogeneous across surveys (p=0.86). The pooled estimate of the odds ratio for the association of alcohol abuse or dependence and heart disease was 1.4, with a confidence interval of 1.0 to 1.9. This marginally significant association was not significant in the subgroup of older respondents (odds ratio 0.8). The 95% confidence intervals of the survey-specific estimates of the adjusted odds ratios for the association of heart disease and alcohol abuse/dependence all included the pooled estimates of the odds ratio. These results suggest that alcohol abuse may occur with greater frequency among persons with heart disease, although the results do not indicate a strong association.

Table 4.

12 month prevalence (%) of substance use disorders among persons with vs. without heart disease

| Alcohol Abuse Dependence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | No Heart Dis | Heart Dis | OR (CI) |

| Colombia | 2.5 | 3.1 | 1.5 (0.3, 7.3) |

| Mexico | 2.2 | 4.2 | 3.2 (0.7, 15.7) |

| United States | 3.2 | 2.2 | 2.4 (1.0, 5.8) |

| Japan | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.6 (0.2, 16.4) |

| Beijing | 2.6 | 1.6 | 2.2 (0.4, 12.5) |

| Shanghai | 0.4 | 0.6 | 2.2 (0.1, 64.7) |

| New Zealand | 3.0 | 0.4 | 0.7 (0.2, 1.9) |

| Belgium | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.6 (0.2, 15.4) |

| France | 0.8 | 0.0 | NE |

| Germany | 1.3 | 0.0 | NE |

| Italy | 0.1 | 0.0 | NE |

| Netherlands | 1.8 | 0.0 | NE |

| Spain | 0.3 | 0.0 | NE |

| Ukraine | 6.7 | 4.6 | 1.4 (0.7, 2.9) |

| Lebanon | 1.1 | 0.0 | NE |

| Nigeria | 0.7 | 0.9 | 2.2 (0.2, 20.1) |

| Israel | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.8 (0.2, 3.8) |

| South Africa | 5.0 | 3.6 | 1.1 (0.5, 2.1) |

| Pooled Odds Ratio | - | - | 1.4 (1.0, 1.9) |

NE means non-estimable

DISCUSSION

This report provides the first assessment of the frequency and association of common mental disorders with self-reported medically diagnosed heart disease in representative population samples from diverse countries world-wide. Two key findings emerged from the present study. First, the well-known association of depression with heart disease – which was replicated here--was actually no stronger than the associations of anxiety disorders with heart disease. This held for the total population and for respondents of 50 years and older as well. The associations persist when adjusted for comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders (data not presented but available on request). Second, since the participating surveys included countries that differed markedly in culture, language, level of socioeconomic development, as well as in prevalence of heart disease and mental disorders, the findings hold across diverse populations, despite concerns about differences in the validity of self-report of medically recognized heart disease that may exist between developed and developing countries.

Although the cross-sectional WMH Survey is causally non-informative, the key findings have implications for current thinking about the depression-heart disease association. Various biobehavioral mechanisms have been proposed to explain this association, including behavioral risk behaviors (e.g. smoking, heavy alcohol use, physical inactivity), poor treatment compliance, elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines, platelet activation, disturbances in the autonomic nervous system (reduced heart rate variability), hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction, and the stressfulness of heart disease related events such as AMI [4-6]. Our results suggest that the implications of anxiety disorder for causal processes may need to be given equal weight with those involving depressive disorders. For instance, one proposed mechanism is poor treatment compliance among depressed heart disease patients, but it has been noted that anxiety disorders are associated with good treatment compliance [36]. Other mechanisms may need to be considered in light of the comorbidity of heart disease with anxiety disorders as well as mood disorders.

While self-reports of medically diagnosed heart disease have generally good validity with Kappa’s exceeding 0.60, considerable underreporting and some overreporting of medically recorded heart disease has typically been found [19-22]. Since the WMH surveys asked specifically for medically diagnosed heart disease, it is less likely that respondents reported atypical chest pain [37] and syndrome X [38], although such error cannot be excluded in a questionnaire survey. Whether any misclassification is non-differential, or produced significant bias, is difficult to determine as conclusive evidence either way is lacking. One prior study has found that negative affectivity (a trait associated with psychological distress) is associated with self-report of physical symptoms, but not with self-report of medically confirmed chronic disease [23]. The results for the depression-heart disease association reported here agree well with prior studies in developed countries that used objectively confirmed heart disease measures. This suggests that it is reasonable to place some confidence in the validity of the association of anxiety disorders with heart disease in developed countries. This confidence may extend to less developed countries since the pattern of association of depression and anxiety disorders did not differ notably between the two types of countries. All this does not negate that the self-report of medically recognized heart disease may differ in their validity in developed versus less developed countries. Neither can we rule out the possibility that those with mental disorder were more likely to seek care for heart disease symptoms and be labeled as having heart disease. This treatment seeking bias (Berkson’s bias) may have inflated associations. Given the overall pattern of results, we think it is possible that misclassification is largely non-differential, and that underestimation of the association between heart disease and mental disorder is slightly more likely than serious bias. The limitation of these survey results invite future research with more rigorous assessment of heart disease status in developing countries than was possible in this series of studies.

Another limitation of the WMH surveys is the lack of more specific assessments of heart disease, both in terms of the nature of the heart disease (e.g. rheumatic heart disease, alcoholic cardiomyopathy) and the course of the disease (e.g. post-MI). More specific assessments will also improve comparability with available studies that focused on specific heart diseases and on specific phases in its course.

The prevalence of heart disease in the WMH surveys conformed to expected epidemiological patterns (i.e. increasing prevalence with age; lower prevalence in relatively poor countries; higher prevalence in males in general). Also the exceedingly high prevalence of heart disease observed for the Ukraine is in line with previous studies finding that many eastern European countries show among the highest cardiovascular disease rates in the world [39]. However, we have no ready explanation for the higher prevalence of heart disease in females than in males in the Ukraine but cultural or linguistic factors might be involved [40]. The 12-month prevalence estimates of major depression among persons with heart disease in western countries were generally lower than has been reported in prior research [6]. This probably has two causes. First, the WMH study used general population samples rather than persons identified in health care settings where the prevalence of depression is higher. Second, the WMH study assessed mental disorders according to a standardized diagnostic instrument rather than the percent exceeding a pre-defined threshold on a self-report depression symptom scale.

Conclusions

The World Mental Health Surveys found that not only mood but also anxiety disorders and to a lesser extent alcohol abuse occurred among persons with heart disease at higher rates than among persons of comparable age and sex without heart disease. This association was observed across diverse countries differing in culture, language, level of socioeconomic development, and prevalence of mental disorders. While this research does not shed light on whether psychological disorders are a cause or a consequence of heart disease, it does suggest that efforts to understand causal relationships between heart disease and psychological illness should consider culture-independent mechanisms that hold for mood as well as anxiety disorders. Since mood and anxiety disorders are associated with many different chronic physical conditions e.g. [6], the depression-heart disease link also needs to be examined in the broader context of chronic medical disease and psychological illness.

Figure 3.

Odds ratio (age-sex adjusted) for alcohol abuse/dependence for persons with vs. without Heart Disease

Acknowledgments

| WMH | The current report was prepared in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and data analysis. These activities were supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R01-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/. |

| China | The Chinese World Mental Health Survey Initiative is supported by the Pfizer Foundation. |

| Colombia | The Colombian National Study of Mental Health (NSMH) is supported by the Ministry of Social Protection, with supplemental support from the Saldarriaga Concha Foundation. |

| ESEMeD Europe | The ESEMeD project is funded by the European Commission (Contracts QLG5-1999-01042; SANCO 2004123), the Piedmont Region (Italy), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (FIS 00/0028), Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain (SAF 2000-158-CE), Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain, and other local agencies and by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. |

| Israel | The Israel National Health Survey is funded by the Ministry of Health with support from the Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research and the National Insurance Institute of Israel. |

| Japan | The World Mental Health Japan (WMHJ) Survey is supported by the Grant for Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health (H13-SHOGAI-023, H14-TOKUBETSU-026, H16-KOKORO-013) from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. |

| Lebanon | The Lebanese National Mental Health Survey (LNMHS) is supported by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, the WHO (Lebanon), anonymous private donations to IDRAC, Lebanon, and unrestricted grants from Janssen Cilag, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Novartis. |

| Mexico | The Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS) is supported by The National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente (INPRFMDIES 4280) and by the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT-G30544- H), with supplemental support from the PanAmerican Health Organization (PAHO). |

| New Zealand | Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey (NZMHS) is supported by the New Zealand Ministry of Health, Alcohol Advisory Council, and the Health Research Council. |

| Nigeria | The Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHW) is supported by the WHO (Geneva), the WHO (Nigeria), and the Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria. |

| South Africa | The South Africa Stress and Health Study (SASH) is supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH059575) and National Institute of Drug Abuse with supplemental funding from the South African Department of Health and the University of Michigan. |

| Ukraine | The Ukraine Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption (CMDPSD) study is funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health (RO1-MH61905). |

| United States | The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust. |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Insel TR, Collins FS. Psychiatry in the genomics era. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:616–620. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ormel J, VonKorff M, Ustun TB, Pini S, Korten A, Oldehinkel T. Common mental disorders and disability across cultures. Results from the WHO Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. JAMA. 1994;272:1741–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.22.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Regional patterns of disability-free life expectancy and disability-adjusted life expectancy: global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1347–1352. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07494-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudisch B, Nemeroff CB. Epidemiology of comorbid coronary artery disease and depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:227–240. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, et al. Depression as a risk factor for coronary artery disease: Evidence, mechanisms, and treatment. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:305–315. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000126207.43307.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, et al. Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Melle JP, de Jonge P, Spijkerman TA, et al. Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:814–822. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146294.82810.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, et al. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3106–3116. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glassman AH, O’Connor CM, Califf RM, et al. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288:701–709. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strik JJMH, Honig A, Lousberg R, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in the treatment of patients with major depression after first myocardial infarction: findings from a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:783–789. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200011000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carney RM, Freedland KE, Jaffe AS. Depression as a risk factor for coronary heart disease mortality. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:229–230. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemingway H, Marmot M. Evidence based cardiology - Psychosocial factors in the aetiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease: systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 1999;318:1460–1467. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7196.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Musselman DL, Marzec U, Davidoff M, et al. Platelet activation and secretion in patients with major depression, thoracic aortic atherosclerosis, or renal dialysis treatment. Depress Anxiety. 2002;15:91–101. doi: 10.1002/da.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kop WJ, Gottdiener JS, Tangen CM, et al. Inflammation and coagulation factors in persons > 65 years of age with symptoms of depression but without evidence of myocardial ischemia. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:419–424. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawachi I, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, Weiss ST. Symptoms of Anxiety and Risk of Coronary Heart-Disease - the Normative Aging Study. Circulation. 1994;90:2225–2229. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.5.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kubzansky LD, Kawachi I, Weiss ST, Sparrow D. Anxiety and coronary heart disease: a synthesis of epidemiological, psychological, and experimental evidence. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20:47–58. doi: 10.1007/BF02884448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Clara I, Asmundson GJG. The relationship between anxiety disorders and physical disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:193–202. doi: 10.1002/da.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barger SD, Sydeman SJ. Does generalized anxiety disorder predict coronary heart disease risk factors independently of major depressive disorder? J Affect Disord. 2005;88:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Center for Health Statistics. Evaluation of National Health Interview Survey - diagnostic reporting. Vital Health Stat 2. 1994;120:1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kriegsman DMW, Penninx BWJH, Eijk JThMv, Boeke AJP, Deeg DJH. Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. A study on the accuracy of patients’ self-reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1407–1417. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kehoe R, Wu SY, Leske MC, Chylack LT., Jr Comparing self-reported and physician-reported medical history. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:813–818. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tretli S, Lund-Larsen PG, Foss OP. Reliability of questionnaire information on cardiovascular disease and diabetes: cardiovascular disease study in Finnmark county. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1982;36:269–273. doi: 10.1136/jech.36.4.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolk AM, Hanewald GJ, Schagen S, Gijsbers van Wijk CM. Predicting medically unexplained physical symptoms and health care utilization. A symptom-perception approach. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergmann MM, Byers T, Freedman DS, Mokdad A. Validity of self-reported diagnoses leading to hospitalization: a comparison of self-reports with hospital records in a prospective study of American adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:969–977. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, et al. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Penninx BWJH, Beekman ATF, Ormel J, et al. Psychological status among elderly people with chronic diseases: does type of disease play a part? J Psychosom Res. 1996;40:521–534. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00620-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stansfeld SA, Fuhrer R, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG. Psychological distress as a risk factor for coronary heart disease in the Whitehall II Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:248–255. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yates WR, Mitchell J, Rush AJ, et al. Clinical features of depressed outpatients with and without co-occurring general medical conditions in STAR*D. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ormel J, Kempen GIJM, Penninx BWJH, Brilman EI, Beekman ATF, Sonderen Ev. Chronic medical conditions and mental health in older people: disability and psychosocial resources mediate specific mental health effects. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1065–1077. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 33.SUDAAN Version 8.0.1. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Belle G, Fisher LD, Heagerty PJ, Lumley T. Biostatistics: A methodology for the health sciences. 2. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bird SM, Cox D, Farewell VT, Goldstein H, Holt T, Smith PG. Performance indicators: good, bad, and ugly. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A. 2005;168:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 36.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment - Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Int Med. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klimes I, Mayou RA, Pearce MJ, Coles L, Fagg JR. Psychological Treatment for Atypical Noncardiac Chest Pain - A Controlled Evaluation. Psychol Med. 1990;20:605–611. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700017116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cannon RO, III, Quyyumi AA, Mincemoyer R, et al. Imipramine in patients with chest pain despite normal coronary angiograms. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1411–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405193302003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: Part II: variations in cardiovascular disease by specific ethnic groups and geographic regions and prevention strategies. Circulation. 2001;104:2855–2864. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.099488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Havenaar JM, Poelijoe NW, Kasyanenko AP, van den Bout J, Koeter MW, Filipenko VV. Screening for psychiatric disorders in an area affected by the Chernobyl disaster: the reliability and validity of three psychiatric screening questionnaires in Belarus. Psychol Med. 1996;26:837–844. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700037867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]